Abstract

Background

The modified Dunn procedure has the potential to restore the anatomy in hips with slipped capital femoral epiphyses (SCFE) while protecting the blood supply to the femoral head and minimizing secondary impingement deformities. However, there is controversy about the risks associated with the procedure and mid- to long-term data on clinical outcomes, reoperations, and complications are sparse.

Questions/Purposes

Among patients treated with a modified Dunn procedure for SCFE, we report on (1) hip pain and function as measured by the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score, Drehmann sign, anterior impingement test, limp, and ROM; (2) the cumulative survivorship at minimum 10-year followup with endpoints of osteoarthritis (OA) progression (at least one Tönnis grade), subsequent THA, or a Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score < 15; (3) radiographic anatomy of the proximal femur measured by slip angle, α angle, Klein line, and sphericity index; and (4) the risk of subsequent surgery and complications.

Methods

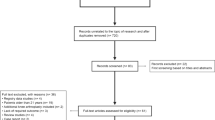

Between 1998 and 2005, all patients who presented to our institution with SCFE were treated with a modified Dunn procedure; this approach was applied regardless of whether the slips were mild or severe, acute or chronic, and all were considered potentially eligible here. Of the 43 patients (43 hips) thus treated during that time, 42 (98%) were available for a minimum 10-year followup (mean, 12 years; range, 10–17 years) and complete radiographic and clinical followup was available on 38 hips (88%). The mean age of the patients was 13 years (range, 9–18 years). Ten hips (23%) presented with a mild, 27 hips (63%) with a moderate, and six hips (14%) with a severe slip angle. Pain and function were measured using the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score, limp, ROM, and the presence of a positive anterior impingement test or Drehmann sign. Cumulative survivorship was calculated according to the method of Kaplan-Meier with three defined endpoints: (1) progression by at least one grade of OA according to Tönnis; (2) subsequent THA; or (3) a Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score < 15. Radiographic anatomy was assessed with the slip angle, Klein line, α angle, and sphericity index.

Results

The Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score improved at the latest followup from 13 ± 2 (7–14) to 17 ± 1 (14–18; p < 0.001), the prevalence of limp decreased from 47% (18 of 38 hips) to 0% (none in 38 hips; p < 0.001), the prevalence of a positive Drehmann sign decreased from 50% (nine of 18 hips) to 0% (none in 38 hips; p < 0.001), and both flexion and internal rotation improved meaningfully. Cumulative survivorship was 93% at 10 years (95% confidence interval, 85%–100%). Radiographic anatomy improved, but secondary impingement deformities remained in some patients, and secondary surgical procedures included nine hips (21%) with screw removal and six hips (14%) undergoing open procedures for impingement deformities. Complications occurred in four hips (9%) and no hips demonstrated avascular necrosis on plain radiographs.

Conclusions

In this series, the modified Dunn procedure largely corrected slip deformities with little apparent risk of progression to avascular necrosis or THA and high hip scores at 10 years. However, secondary impingement deformities persisted in some hips and of those some underwent further surgical corrections.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In situ fixation has been the most commonly performed treatment in hips with slipped capital femoral epiphyses (SCFE) [49]. Although this procedure allows for stabilization of the epiphysis, it does not correct the residual deformity of the proximal femur. Secondary impingement deformities after SCFE can result in early joint degeneration, loss of hip function, and premature osteoarthritis (OA) [12, 13, 41]. Even a mild or stable slip can result in impingement and the development of OA [2, 42, 60, 73]. Although the deformity after severe slips leads to abutment of the metaphysis to the acetabular rim and labrum (impaction-type impingement), the cam-type asphericity after mild slips can enter the joint in flexion resulting in cartilage delamination (inclusion-type impingement) [34]. Historically, surgical methods of epiphyseal realignment have been associated with a high number of complications including the devastating avascular necrosis of the epiphysis [6, 25, 32, 65, 72]. The modified Dunn procedure offers the potential to restore the anatomy of the proximal femur and impingement-free ROM while securing epiphyseal perfusion. It was first performed at our institution in 1998 [44, 61, 76]. The modification compared with Dunn’s original description [19, 20] includes surgical dislocation [26] of the hip combined with the development of the soft tissue retinacular flap [27] including the branches for epiphyseal perfusion. The technique allows anatomic reduction under visual control of the epiphyseal vascularity.

A subset of 30 hips (30 patients) following the modified Dunn procedure performed at our institution showed promising results at a mean followup of 5 years without the risk of avascular necrosis [76]. However, others have reported on an increased risk of avascular necrosis after this procedure [54, 56, 62, 70] and the risks associated with this procedure remain controversial. In addition, mid- to long-term data on clinical outcomes, reoperations, and complications are sparse. Therefore, we were interested in the mid- to long-term results, potential benefits, and complications of the modified Dunn procedure performed at the originator’s institution.

We therefore evaluated (1) hip pain and function as measured by the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score, Drehmann sign, anterior impingement test, limp, and ROM; (2) cumulative survivorship at minimum 10-year followup with endpoints of OA progression (Tönnis grade), subsequent THA, and a Merle d’Aubigné score < 15; (3) radiographic anatomy of the proximal femur measured by slip angle, α angle, Klein line, and sphericity index; and (4) risk of subsequent surgery and complications in hips undergoing the modified Dunn procedure for SCFE.

Patients and Methods

We evaluated the minimum 10-year survivorship of the first 43 patients (43 hips) who underwent the modified Dunn procedure [76] for SCFE at our institution. Thirty patients (30 hips [70%]) were part of a previous study investigating the minimum 3-year results [76]. Between 1998 and 2005, all patients who presented to our institution with SCFE were treated with a modified Dunn procedure; this approach was applied regardless of whether the slips were mild or severe, acute or chronic, and all were considered potentially eligible here. The mean age at operation was 13 ± 2 (range, 9–18) years and 23 patients (23 hips [53%]) were male (Table 1). Five patients (five hips [12%]) presented with an unstable hip according to Loder [45]. A majority of 27 hips (63%) presented with a moderate slip angle according to Southwick [63] ranging from 30° to 60°. Ten hips (23%) presented with a mild slip angle of less than 30° and six hips (14%) with a severe angle exceeding 60°. Twenty-five hips (58%) had an acute or acute on chronic slip (Table 1). No patient had bilateral SCFE. Of the 43 hips, 37 (86%) had prophylactic pinning performed on the contralateral side.

Of the 43 patients (43 hips) thus treated during that time, 42 patients (42 hips [98%]) were available for followup at a minimum 10 years and complete radiographic and clinical followup was available on 38 patients (38 hips [88%]). One patient (one hip [2%]) was lost before minimum 10-year followup. This patient presented 6 years postoperatively with good clinical results (Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score of 16, no limp, negative Drehmann sign, or anterior impingement test) and no signs of OA or avascular necrosis on the most recent conventional radiographs. This patient was excluded from the clinical 10-year results but included for survivorship analysis because the applied statistical test (method of Kaplan-Meier) allows including censored data. The remaining 42 patients (42 hips) were available for a mean followup of 12 years (range, 10–17 years). Of those, four patients (four hips [9%]) declined to return for clinical and radiographic examination; therefore, only mailed questionnaires and telephone interviews were available at the 10-year followup for these patients. These four patients (four hips [9%]) had a radiographic followup between 5 and 8 years after surgery with no signs of OA or avascular necrosis. These hips were excluded from the clinical 10-year results. The local institutional review board approved this retrospective case series.

The operative technique of the modified Dunn procedure has been previously described [27, 43, 44]. Briefly, the patient was placed in a lateral decubitus position and the surgical dislocation of the hip with an osteotomy of the greater trochanter was performed [26]. An extended retinacular soft tissue flap [27] was developed to preserve the blood supply to the femoral head. The capital epiphysis was first completely separated from the femoral neck, which allows full exposure of the femoral neck and visualization of the posteroinferior callus formation on the neck. This callus formation has to be removed completely so as not to create a fulcrum and tension on the terminal branches of the medial femoral circumflex artery after reduction of the epiphysis [43]. While manually stabilizing the femoral head, the remaining physis of the femoral head was removed with a burr or curette [43]. After gentle reduction of the femoral head back onto the femoral neck, the femoral head was stabilized using a threaded wire inserted in an anterograde manner through the fovea capitis [43, 76]. In addition, the femoral head was stabilized with a second threaded wire placed in a distal to proximal direction under fluoroscopic guidance [43, 76]. In the period in question, the first seven of 43 hips (16%) had stabilization of the epiphysis using 3.5-mm cortical screws. Because screw breakage occurred in four hips of these seven hips (57%), stabilization in the following cases was performed using threaded wires (with breakage in one of 36 hips [3%]). Epiphyseal perfusion was checked on a regular basis before and after reduction of the epiphysis using a 2-mm drill hole to observe bleeding. In selected hips in the current series, a laser Doppler flowmetry probe was used additionally to check epiphyseal perfusion [58]. In all but one hip epiphyseal perfusion could be confirmed. In one hip with an unstable slip, epiphyseal perfusion could not be confirmed using a drill hole and laser Doppler flowmetry following the modified Dunn procedure and epiphyseal realignment (Fig. 1) [58]. At revision surgery 2 months later for wire breakage, epiphyseal perfusion was reassessed and a normal signal could be recorded (Fig. 1). At 14.5-year followup, this patient showed union of the epiphysis without avascular necrosis or THA (Fig. 1).

(A) An acute and moderate SCFE occurred in an obese 12-year-old boy. (B) A modified Dunn procedure was performed to realign and refixate the femoral epiphysis. (C, columns A–D) During surgery, epiphyseal perfusion was measured using laser Doppler flowmetry. No epiphyseal perfusion was present before and after epiphyseal realignment. However, at the level of the retinaculum a pulse signal was found. (D) Four days after surgery a bone scintigraphy verified the missing perfusion of the left femoral head (see difference in enhancement between the femoral heads). (E) Two months later, a repeated bone scintigraphy was performed showing normal perfusion of the left femoral head. A possible explanation could be a spasm of the most distal retinacular vessels. (F) As a result of breakage of one wire for fixation of the epiphyses, revision surgery with screw refixation of the epiphysis was performed. (C, column E) During revision surgery, a normal pulsatile signal of the epiphysis was encountered with the laser Doppler flowmetry. (G) At 14-year followup, no sign of avascular necrosis was seen on the conventional radiograph. Reprinted from Schoeninger R, Kain MS, Ziebarth K, Ganz R. Epiphyseal reperfusion after subcapital realignment of an unstable SCFE. Hip Int. 2010;20:273–279. Copyright Wichtig Editore 2010. Reproduced with permission.

Clinical evaluation at most recent followup was performed by two of the authors (MM, TDL, both not involved in the surgical care of the patients) in 38 patients (38 hips [88%]). Clinical evaluation included assessment of limp, the presence of a positive anterior impingement test (pain in combined flexion and internal rotation), the presence of a positive Drehmann sign [18] (passive external rotation with increasing flexion and the inability of active internal rotation), and full goniometric ROM. The Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score [15] was used as a clinical scoring system. Because evaluation of the anterior impingement test, Drehmann sign, and ROM preoperatively in hips with acute SCFE is not advocated, these parameters were only evaluated in the 18 hips with chronic SCFE. The clinical results of the contralateral side without SCFE at 10-year followup were added for comparison. Different observers performed the clinical evaluations preoperatively and at followup. However, substantial inter- and intraobserver agreement has been reported for the anterior impingement test [47], ROM [33, 48, 74], the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score [38], and the Drehmann sign in patients with SCFE [36].

We calculated survival rate at the 10-year followup and defined failure if any of the following occurred: conversion to THA, progression of OA by at least one grade according to Tönnis [68], or a Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score of < 15 at most recent followup. The four hips (four patients [9%]) that had only questionnaire and telephone followup at 10-year followup were considered as surviving hips because they did not show signs of OA at most recent followup ranging from 5 to 8 years. These four patients did not undergo conversion to THA and presented with good to excellent clinical results at most recent followup (Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score ranging between 15 and 18, Harris hip score between 81 and 95, and WOMAC score between 0 and 10). These clinical results make OA progression very unlikely.

Radiographic evaluation included an AP pelvis radiograph and cross-table lateral or Lauenstein view. Slippage of the epiphysis was quantified using the slip angle [63] and the intactness of the Klein line [39]. Femoral head-neck offset was evaluated with the α angle [51] in the AP and axial view. Sphericity at followup was quantified with the sphericity index [64] (ratio of minor to major axis of the ellipse drawn to best fit the femoral head). In addition, the neck shaft angle and nine standardized radiographic parameters to evaluate the radiographic anatomy of the acetabulum were assessed. The radiographic parameters were assessed by one observer (TDL; not involved in the surgical care of the patients) with the help of previously developed and validated computer software Hip2Norm (University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland) [66, 67, 75]. OA was graded according to Tönnis [68].

Subsequent surgical procedures and complications were summarized using medical chart review. Complications were graded according to Sink et al. [59] (an adapted Dindo-Clavien classification [14, 17] for orthopaedic surgery). Grade I complications require no treatment, have no clinical relevance, and no deviation from routine followup. Grade II complications require deviation from the normal postoperative course and outpatient treatment. Grade III complications require surgical or radiologic interventions or an unplanned hospital admission. Grade IV complications are life-threatening or have the potential for permanent disability. Death is a Grade V complication [14, 17, 59]. Grade 1 complications were not included as a result of the retrospective nature of the study.

Normal distribution of all continuous parameters was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Because most parameters were not normally distributed, we only used nonparametric tests. Clinical results at followup were compared with the preoperative status and the contralateral hip using the Wilcoxon test and the Mann-Whitney U-test, respectively. We tested differences for radiograph results among the preoperative, postoperative, and followup using the Friedman test for continuous variables. If differences existed, pairwise comparison was performed with the Wilcoxon test. Binominal data were compared using the chi square or Fisher’s exact tests. Cumulative survivorship was calculated according to Kaplan-Meier [37] with the endpoints defined as conversion to THA, progression of at least one grade of OA according to Tönnis [68], or a Merle d’Aubigné score < 15. Differences among survivorship curves (mild, moderate, and severe slip) were compared using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using Winstat software (R. Fitch Software, Bad Krozingen, Germany).

Results

Hip function was improved and pain was decreased at latest followup in hips following the modified Dunn procedure for SCFE. No difference was found in comparison to the contralateral hip without SCFE at followup (Table 2). In hips with SCFE and the modified Dunn procedure, the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score improved from preoperatively 13 ± 2 (7–14) to 17 ± 1 (14–18; p < 0.001) at latest followup, the prevalence of limp decreased from 47% (18 of 38 hips) to 0% (none in 38 hips; p < 0.001), the prevalence of a positive Drehmann sign decreased from 50% (nine of 18 hips) to 0% (none in 38 hips; p < 0.001), flexion improved from 58° ± 32° (10°–100°) to 104° ± 12° (70°–120°; p = 0.003), and internal rotation improved from 6° ± 8° (0°–25°) to 32° ± 15° (5°–60°; p < 0.001). At followup, no difference existed between the hip after the modified Dunn procedure and the contralateral asymptomatic side with prophylactic pinning for the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score, prevalence of limp, prevalence of a positive anterior impingement test, prevalence of a positive Drehmann sign, or ROM (Table 2).

Using the three endpoints defined as OA progression, conversion to THA, or a Merle d’Aubigné score < 15, the cumulative 10-year survivorship was 93% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85%–100%) (Fig. 1). At the latest followup, seven of 43 hips (16%) reached at least one of the three endpoints: four hips showed progression of OA (Fig. 2), three patients had a Merle d’Aubigné score < 15, and none underwent conversion to THA. Four of these endpoints were reached after more than 10 years after the initial operation. No difference in survivorship existed among hips with a mild slip (100%; 95% CI, 100%–100%), moderate slip (92%; 95% CI, 82%–100%), or severe slip (86%; 95% CI, 60%–100%; p = 0.311; Fig. 2).

The cumulative 10-year survivorship was calculated according to Kaplan-Meier [37] using the three endpoints: conversion to THA, progression of OA according to Tönnis [68], or a Merle d’ Aubigné score < 15 points at followup. The overall cumulative 10-year survivorship was 93% (95% CI, 85%–100%). We found no difference in survivorship among hips with a mild slip (100%; 95% CI, 100%–100%), moderate slip (92%; 95% CI, 82%–100%), or a severe slip (86%; 95% CI, 60%–100%; p = 0.311).

Following the modified Dunn procedure, the radiographic anatomy of the proximal femur in hips with SCFE was improved in the vast majority (Table 3). The slip angle improved from 43° ± 17° (15°–80°) to 9° ± 10° (−15° to 30°; p < 0.001), the α angle in the axial or Lauenstein view decreased from 84 ± 14 (59–104) to 48 ± 14 (23–87; p < 0.001), the α angle in the AP view decreased from 70 ± 15 (38–94) to 49 ± 9 (37–68; p < 0.001), and the proportion of hips with a positive Klein line decreased from 58% (25 of 43 hips) to 0% (none of 43 hips). Postoperatively, the sphericity index of the femoral head was at least 80% (mean 93% ± 0.07% [80%–98%]).

Subsequent surgical procedures were performed in 14 of 43 hips (33%) and complications occurred in four of 43 hips (9%; Table 4). Subsequent procedures included nine hips (21%) undergoing screw removal, four hips (9%) with open offset correction, and two hips (5%) with combined open offset correction and acetabular rim trimming (Table 4). All five hips (12%) with complications were graded Grade 3 according to Sink et al. [59] (complication requiring reoperation without potential of permanent disability). They were performed for breakage of screws or wires for epiphyseal fixation in four hips (9%) requiring additional fixation or pseudarthrosis of the greater trochanter after breakage of the trochanteric screws in one hip (2%) requiring reosteosynthesis (Table 4). All epiphyseal refixations and the trochanteric osteotomy ultimately healed. Using plain radiographs, no signs of avascular necrosis were observed in any hip during followup.

Discussion

In situ fixation has been the most commonly performed treatment in hips with SCFE [49]. It offers control for physeal instability; however, it is not used for correction of a secondary deformity and the resulting femoroacetabular impingement in hips with SCFE [49]. Even a mild slip can result in impingement and the development of OA [2, 42, 49, 60]. Historically, surgical methods of realignment have been associated with a high number of complications [3, 7, 9–11, 24, 40, 50, 55, 57] with the risk of avascular necrosis reportedly ranging up to 54% [28] (Table 5). The modified Dunn procedure with realignment of the epiphysis offers the potential to restore the anatomy of the proximal femur and impingement-free ROM. In addition, this procedure allows to control the epiphyseal vascularity and to restore epiphyseal perfusion. Early results showed promising results [61, 76]. However, no long-term reports for this procedure have been published. At 10-year followup, we found improved hip function and decreased pain in hips after the modified Dunn procedure for SCFE compared with the preoperative status. The Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score, flexion, and internal rotation were increased and the prevalence of limp or a positive Drehmann sign decreased (Table 2). No difference existed compared with the contralateral side without epiphyseal slippage and prophylactic pinning (Table 2). In 93% of the hips at the 10-year followup, we found a good to excellent result with no progression of OA. Postoperatively, the radiographic anatomy of the proximal femur was improved in the vast majority of hips. Five hips (12%) had complications requiring refixation of the epiphysis or reosteosynthesis of the greater trochanter (Table 4). Offset correction was performed in six hips (14%). No hip showed signs of avascular necrosis at latest followup.

The study has several limitations. First, there is a lack of a control group with different treatments, and so our results can only be compared with those published by others (Table 5). Second, the clinical evaluation was done by different observers preoperatively and at followup as a result of the retrospective design and a long span of followup. However, substantial inter- and intraobserver agreement has been reported for the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score [38], anterior impingement test [47], Drehmann sign in patients with SCFE [36], and ROM [33, 48, 74]. Therefore, we believe this issue is unlikely to have biased our clinical results to a relevant degree. Third, the preoperative testing of the anterior impingement test, Drehmann sign, or ROM is not advocated in unstable slips and, therefore, these data were missing. We compared the clinical results at 10-year followup to the asymptomatic, contralateral side with prophylactic pinning. However, this could have biased the comparison because the contralateral hip is more likely to have an altered morphology as a result of a potential silent slip. Fourth, all hips with SCFE during the period in question were treated with the modified Dunn procedure independent of the amount of slippage. Current treatment options at our clinic include in situ pinning with arthroscopic offset improvement in hips with a minimal slip (slip angle < 15°). Decision-making is based on a preoperative hip MRI with radial slices to quantify the amount of slippage. At the period in question all hips with SCFE underwent the modified Dunn procedure including those with a minimal slip. Therefore, the results with today’s indication for the modified Dunn procedure could be somewhat inferior because hips with a minimal slip (associated with superior clinical results and a decreased rate of complications) would no longer be included. Next, one of 43 patients (one hip [2%]) was not available for a minimum 10-year followup. This patient had a good clinical result and no signs of avascular necrosis on the AP radiograph 6 years postoperatively; therefore, it is unlikely that he would have developed avascular necrosis at the 10-year followup. Last, we did not screen for avascular necrosis using MRI. However, all hips had confirmed epiphyseal perfusion checked intraoperatively with a drill hole and in selected cases with an additional laser Doppler flowmetry probe. The missing signs of avascular necrosis on the conventional radiograph at the long-term followup give reassurance that no hip developed avascular necrosis.

In the current series, hip function was improved and pain was decreased 10 years after the modified Dunn procedure (Fig. 3). No difference was found compared with the asymptomatic hip with prophylactic pinning (Table 2). These results are in line with reported results for the modified Dunn procedure showing improvement in clinical scores, flexion, and internal rotation at a mean 3-year followup [46]. Others reported on a minimal flexion of 90° in all hips and an excellent result (defined as a Harris hip score [29] exceeding 95 points) in 93% of hips following the modified Dunn procedure at the 4-year followup [35]. Comparing the modified Dunn procedure with in situ pinning in hips with severe and stable slips showed superior clinical results (using the Heyman and Herndon classification [30, 31]) for the modified Dunn procedure at an early followup of 2.5 years [52]. In a previously published subset of 30 hips from the current series, a comparable result for the Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score (average, 18; range, 17–18) was found at the mean 5-year followup [76]. In the same study, no difference was found for the Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score between the operated hip and the asymptomatic hip with prophylactic pinning [76].

A 12-year-old girl with an acute and stable SCFE and slip angle of 36° (moderate slip) is shown preoperatively (A), following the modified Dunn procedure (B), and at 1-year (C), 2-year (D), and 10-year followup (E). Partial metal removal has been performed (E). The preoperative Lauenstein view (F) shows a slip angle of 36° and restoration of the femoral anatomy postoperatively (G) and at 2-year followup (H). Final outcome after partial metal removal was a pain-free hip with a Harris hip score of 95 points without signs of OA on the AP and lateral radiographs (E, I) at 10-year followup.

At the 10-year followup, the cumulative survivorship free from arthritis progression, conversion to THA, or a Merle d’Aubigné score < 15 was 93% (95% CI, 85%–100%; Fig. 2). No difference was found in survivorship among hips with mild, moderate, or severe slips (Fig. 2). Four hips (9%) showed progression of OA between 10 and 17 years followup in the current study (Fig. 4). Others have reported comparable results with 3% of OA at a mean 13-year followup using the original Dunn reduction procedure in a publication of its originator [10]. Using the cuneiform neck osteotomy, OA at a mean 13-year followup was found in 9% of the hips [21]. Most reports with a minimal 10-year followup after surgical treatment of hips with SCFE showed an increased percentage of hips with OA compared with the current series. After in situ pinning, 38% to 39% of hips had reported progression of OA at a mean followup of 11 and 31 years [8, 9]. With increasing severity of the slip, the percentage of hips with OA increased from 33% in mild slips to 41% in moderate slips and 60% in severe slips [9]. Hips after subcapital or neck osteotomies showed OA in 40% to 45% of hips at a mean followup ranging from 10 to 16 years [6, 71, 72]. With an osteotomy at the intertrochanteric level, the percentage of hips with OA was increased and ranged from 37% to 70% at a mean followup from 10 to 24 years [6, 24, 57]. No hip in the current study converted to THA at a minimum 10-year followup. Most studies reporting on the modified Dunn procedure at a mean followup from 1 to 5 years (Table 5) did not report on conversion to THA except in two studies [52, 56]. In these two studies, each study reported one hip converting to THA at short-term followup of 2 years (percentage of conversion to THA of 2% and 7%) [52, 56]. With a minimal 10-year followup, other studies reported on a rate of conversion to THA after subcapital osteotomies ranging from 1% to 11% [6, 10, 50, 71, 72] (mean followup ranging from 10 to 16 years) and from 0% to 13% for intertrochanteric osteotomies (mean followup ranging from 19 to 24 years) [24, 57, 69]. Carney et al. [12] evaluated several surgical treatments for hips with SCFE including in situ pinning and hips without surgical treatment and found a conversion to THA in 37% at a mean followup of 41 years. The decreased percentage of hips with OA and the lack of hips with conversion to THA in the current series at a minimum 10-year followup support the concept that correction of the residual deformity after SCFE and elimination of impingement would result in decreased degenerative changes.

A 14-year-old boy with a stable, acute on chronic SCFE (symptoms lasting for 8 months) and a slip angle of 60° (severe slip) is shown preoperatively (A); intraoperative view (B) after surgical dislocation of the femoral head revealed severe cartilage damage (L = labrum, F = fossa, arrows showing cartilage delamination); postoperative anatomic alignment after a modified Dunn procedure (C); and after an attempt for revision surgery through a surgical hip dislocation for débridement of the joint and partial screw removal 1.5 years after the initial operation (D). At the 10-year followup, progression to OA is shown (OA Grade 2) (E, H). Preoperative Dunn view (F) and postoperative Lauenstein view (G) are shown. Figure 4B reprinted from Slongo T, Kakaty D, Krause F, Ziebarth K. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a modified Dunn procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2898–2908. Copyright Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

Normal radiographic anatomy of the hip could be restored in the majority of the hips after the modified Dunn procedure in the current series (Fig. 4). Improvements in the slip angle, α angle, and the percentage of an intact Klein’s line (Table 3) indicate the potential for deformity correction of the modified Dunn procedure. Largely normal-appearing hip morphology after a modified Dunn procedure was uniformly reported for the slip angle [35, 54, 56] and the α angle [54]. Despite a described potential for remodeling [53], in situ pinning for moderate to severe slips has been shown to leave the hip with residual cam deformities and compromised hip function [13, 52]. At a mean 22-year followup after in situ pinning, 80% of the hips presented with a pistol grip deformity [13]. Normal-appearing hip morphology was reported after subcapital osteotomy for the slip angle for severe SCFE [23] and after in situ pinning for mild SCFE for the α angle on cross-table radiographs [22]. However, the mean α angle on AP radiographs (mean, 86°; range, 55°–99°) was increased and a reduced or absent head-neck ratio was found in 63% (10 of 16 hips) 14 years after in situ pinning [22].

The rate of subsequent surgery and complications in the current series (Table 4) is comparable to that found in the literature for the modified Dunn procedure (Table 5). The rate of revision surgery resulting from hardware failure of epiphyseal fixation (9% in the current series; Table 4) ranged from 7% to 15% [35, 52, 56, 76]. In addition, an increased risk of implant breakage of 20% was found for the use of cortical screws compared with threaded wires not showing any breakage [35, 56]. The rate of subsequent surgery for improvement of secondary deformities and impingement (14% in the current series; Table 4) ranged from 0% to 16% [35, 46, 52, 56, 61, 70, 76]. With the hips available in the current series we found no avascular necrosis following the modified Dunn procedure. In contrast to our results, all but one author [76] reported on the risk of avascular necrosis after the modified Dunn procedure with a wide range from 3% to 29% [35, 46, 52, 54, 61, 62, 70] (Table 5). Possible explanations for this difference could be the increased percentage of mild and stable slips in the current series, no previous interventions, or the long experience with hip-preserving surgery at the current institution. Generally, hips following the modified Dunn procedure showed no increased risk of avascular necrosis compared with other surgical treatments (Table 5). After in situ pinning, the rate of avascular necrosis ranged from 0% to 13% [4, 5, 8, 11, 40, 41, 50] with the highest value of 43% for pinning in unstable hips only [62]. Hips with epiphyseal realignment using a neck or subcapital osteotomy without surgical hip dislocation or the development of a retinacular soft tissue flap showed the highest risk of avascular necrosis with a rate up to 54% (Table 5) [1, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 16, 21, 23, 25, 28, 32, 40, 50, 65, 71, 72]. Extracapsular corrections at the intertrochanteric level showed a decreased risk of avascular necrosis ranging from 0% to 6% (Table 5) [6, 11, 24, 50, 57, 63, 69].

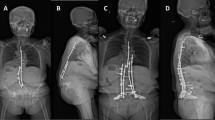

A 15-year-old girl with stable and acute on chronic SCFE and a slip angle of 40° (moderate slip) is shown preoperatively (A), following the modified Dunn procedure (B), after screw breakage 3 months postoperatively as a result of early weightbearing (C), after revision surgery for osteosynthesis (D), and at 15-year followup (E). The abduction view preoperatively (F), the Lauenstein view postoperatively (G), after revision surgery (H), and at 16-year followup (I) are shown. This is the very first patient treated with a modified Dunn procedure at our institution; the body mass index at the time of operation was 26 kg/m2 and the patient did not adhere to strict restricted weightbearing. Final outcome was favorable with a well-functioning hip and a Harris hip score of 91 points at 16-year followup.

In conclusion, the modified Dunn procedure successfully restored hip anatomy and hip function in the majority of hips in this series, which were predominantly stable, moderate, to severe SCFEs. At a mean 12-year followup, no hip showed avascular necrosis or conversion to a THA. The cumulative 10-year survival rate was 93% free from progression of OA, conversion to THA, or poor clinical outcome. Capital realignment in this patient group led to restoration of the proximal femoral anatomy and improved hip function. However, residual deformities can persist and subsequent surgical improvement might be needed. Surgical hip dislocation with the development of a retinacular soft tissue flap allows to control the epiphyseal vascularity and restore epiphyseal perfusion in hips with SCFE. The results confirm that a slipped capital epiphysis can be realigned and fixed safely with no substantial risk for avascular necrosis when performed correctly, at the same time reducing the underlying deformity. We are aware that some have reported less favorable results regarding avascular necrosis with this surgical technique. [46, 56, 62, 70]. However, we are positive that extensive experience with surgical hip dislocation and development of the retinacular flap combined with a profound knowledge of the vascular anatomy of the femoral epiphysis and a meticulous surgical technique will lead to reproducible results. If these prerequisites are not given, we recommend temporary in situ pinning of hips with SCFE followed by immediate referral to a center of expertise in hip-preserving surgery. Restoration of the original anatomy is the goal to avoid subsequent early hip degeneration, pain, and the need for THA in young and active patients with SCFE.

References

Abraham E, Garst J, Barmada R. Treatment of moderate to severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis with extracapsular base-of-neck osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:294–302.

Abraham E, Gonzalez MH, Pratap S, Amirouche F, Atluri P, Simon P. Clinical implications of anatomical wear characteristics in slipped capital femoral epiphysis and primary osteoarthritis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:788–795.

Adorjan I. On the treatment of advanced slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1961;30:286–293.

Aronson DD, Carlson WE. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A prospective study of fixation with a single screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:810–819.

Aronson DD, Peterson DA, Miller DV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. The case for internal fixation in situ. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:115–122.

Ballmer PM, Gilg M, Aebi B, Ganz R. Results following sub-capital and Imhäuser-Weber osteotomy in femur head epiphyseolysis. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1990;128:63–66.

Barmada R, Bruch RF, Gimbel JS, Ray RD. Base of the neck extracapsular osteotomy for correction of deformity in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;132:98–101.

Bellemans J, Fabry G, Molenaers G, Lammens J, Moens P. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a long-term follow-up, with special emphasis on the capacities for remodeling. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:151–157.

Boyer DW, Mickelson MR, Ponseti IV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Long-term follow-up study of one hundred and twenty-one patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:85–95.

Broughton NS, Todd RC, Dunn DM, Angel JC. Open reduction of the severely slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:435–439.

Carlioz H, Vogt JC, Barba L, Doursounian L. Treatment of slipped upper femoral epiphysis: 80 cases operated on over 10 years (1968-1978). J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:153–161.

Carney BT, Weinstein SL, Noble J. Long-term follow-up of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:667–674.

Castañeda P, Ponce C, Villareal G, Vidal C. The natural history of osteoarthritis after a slipped capital femoral epiphysis/the pistol grip deformity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S76–82.

Clavien PA, Strasberg SM. Severity grading of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:197–198.

D’aubigne RM, Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36:451–475.

DeRosa GP, Mullins RC, Kling TF. Cuneiform osteotomy of the femoral neck in severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:48–60.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213.

Drehmann F. [Drehmann’s sign. A clinical examination method in epiphysiolysis (slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis). Description of signs, aetiopathogenetic considerations, clinical experience (author’s transl)]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1979;117:333–344.

Dunn DM. The treatment of adolescent slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:621–629.

Dunn DM, Angel JC. Replacement of the femoral head by open operation in severe adolescent slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60:394–403.

Fish JB. Cuneiform osteotomy of the femoral neck in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A follow-up note. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:46–59.

Fraitzl CR, Käfer W, Nelitz M, Reichel H. Radiological evidence of femoroacetabular impingement in mild slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a mean follow-up of 14.4 years after pinning in situ. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1592–1596.

Fron D, Forgues D, Mayrargue E, Halimi P, Herbaux B. Follow-up study of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis treated with Dunn’s osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:320–325.

Fujak A, Müller K, Legal W, Legal H, Forst R, Forst J. Long-term results of Imhäuser osteotomy for chronic slipped femoral head epiphysiolysis. Orthopade. 2012;41:452–458.

Gage JR, Sundberg AB, Nolan DR, Sletten RG, Winter RB. Complications after cuneiform osteotomy for moderately or severely slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:157–165.

Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1119–1124.

Ganz R, Huff TW, Leunig M. Extended retinacular soft-tissue flap for intra-articular hip surgery: surgical technique, indications, and results of application. Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:241–255.

Hall JE. The results of treatment of slipped femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39:659–673.

Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755.

Herndon CH, Heyman CH, Bell DM. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis by epiphyseodesis and osteoplasty of the femoral neck. A report of further experiences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:999–1012.

Heyman CH, Herndon CH. Epiphyseodesis for early slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36:539–555.

Hiertonn T. Wedge osteotomy in advanced femoral epiphysiolysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1955;25:44–62.

Holm I, Bolstad B, Lütken T, Ervik A, Røkkum M, Steen H. Reliability of goniometric measurements and visual estimates of hip ROM in patients with osteoarthrosis. Physiother Res Int. 2000;5:241–248.

Hosalkar HS, Pandya NK, Bomar JD, Wenger DR. Hip impingement in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a changing perspective. J Child Orthop. 2012;6:161–172.

Huber H, Dora C, Ramseier LE, Buck F, Dierauer S. Adolescent slipped capital femoral epiphysis treated by a modified Dunn osteotomy with surgical hip dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:833–838.

Kamegaya M, Saisu T, Nakamura J, Murakami R, Segawa Y, Wakou M. Drehmann sign and femoro-acetabular impingement in SCFE. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:853–857.

Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481.

Kirmit L, Karatosun V, Unver B, Bakirhan S, Sen A, Gocen Z. The reliability of hip scoring systems for total hip arthroplasty candidates: assessment by physical therapists. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:659–661.

Klein A, Joplin RJ, Reidy JA, Hanelin J. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis; early diagnosis and treatment facilitated by normal roentgenograms. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1952;34:233–239.

Kulick RG, Denton JR. A retrospective study of 125 cases of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;162:87–90.

Larson AN, Sierra RJ, Yu EM, Trousdale RT, Stans AA. Outcomes of slipped capital femoral epiphysis treated with in situ pinning. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32:125–130.

Leunig M, Casillas MM, Hamlet M, Hersche O, Nötzli H, Slongo T, Ganz R. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: early mechanical damage to the acetabular cartilage by a prominent femoral metaphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:370–375.

Leunig M, Slongo T, Ganz R. Subcapital realignment in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: surgical hip dislocation and trimming of the stable trochanter to protect the perfusion of the epiphysis. Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:499–507.

Leunig M, Slongo T, Kleinschmidt M, Ganz R. Subcapital correction osteotomy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis by means of surgical hip dislocation. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19:389–410.

Loder RT. Unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:694–699.

Madan SS, Cooper AP, Davies AG, Fernandes JA. The treatment of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis via the Ganz surgical dislocation and anatomical reduction: a prospective study. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:424–429.

Martin RL, Sekiya JK. The interrater reliability of 4 clinical tests used to assess individuals with musculoskeletal hip pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:71–77.

McWhirk LB, Glanzman AM. Within-session inter-rater reliability of goniometric measures in patients with spastic cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2006;18:262–265.

Millis MB, Novais EN. In situ fixation for slipped capital femoral epiphysis: perspectives in 2011. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(Suppl 2):46–51.

Nishiyama K, Sakamaki T, Ishii Y. Follow-up study of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:653–659.

Nötzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:556–60.

Novais EN, Hill MK, Carry PM, Heare TC, Sink EL. Modified Dunn procedure is superior to in situ pinning for short-term clinical and radiographic improvement in severe stable SCFE. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:2108–2117.

O’Brien ET, Fahey JJ. Remodeling of the femoral neck after in situ pinning for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:62–68.

Persinger F, Davis RL, Samora WP, Klingele KE. Treatment of unstable slipped capital epiphysis via the modified Dunn procedure. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016 Feb 10. [Epub ahead of print].

Rao JP, Francis AM, Siwek CW. The treatment of chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis by biplane osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1169–1175.

Sankar WN, Vanderhave KL, Matheney T, Herrera-Soto JA, Karlen JW. The modified Dunn procedure for unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a multicenter perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:585–591.

Schai PA, Exner GU. Corrective Imhäuser intertrochanteric osteotomy. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19:368–388.

Schoeniger R, Kain MSH, Ziebarth K, Ganz R. Epiphyseal reperfusion after subcapital realignment of an unstable SCFE. Hip Int. 2010;20:273–279.

Sink EL, Leunig M, Zaltz I, Gilbert JC, Clohisy J, Academic Network for Conservational Hip Outcomes Research Group. Reliability of a complication classification system for orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2220–2226.

Sink EL, Zaltz I, Heare T, Dayton M. Acetabular cartilage and labral damage observed during surgical hip dislocation for stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:26–30.

Slongo T, Kakaty D, Krause F, Ziebarth K. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a modified Dunn procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2898–2908.

Souder CD, Bomar JD, Wenger DR. The role of capital realignment versus in situ stabilization for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34:791–798.

Southwick WO. Osteotomy through the lesser trochanter for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49:807–835.

Steppacher SD, Tannast M, Werlen S, Siebenrock KA. Femoral morphology differs between deficient and excessive acetabular coverage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:782–790.

Szypryt EP, Clement DA, Colton CL. Open reduction or epiphysiodesis for slipped upper femoral epiphysis. A comparison of Dunn’s operation and the Heyman-Herndon procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:737–742.

Tannast M, Mistry S, Steppacher SD, Reichenbach S, Langlotz F, Siebenrock KA, Zheng G. Radiographic analysis of femoroacetabular impingement with Hip2Norm-reliable and validated. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1199–205.

Tannast M, Zheng G, Anderegg C, Burckhardt K, Langlotz F, Ganz R, Siebenrock KA. Tilt and rotation correction of acetabular version on pelvic radiographs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:182–190.

Tönnis D. General radiography of the hip joint. In: Tönnis D, ed. Congenital Dysplasia, Dislocation of the Hip. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1987.

Trisolino G, Pagliazzi G, Di Gennaro GL, Stilli S. Long-term results of combined epiphysiodesis and Imhauser intertrochanteric osteotomy in SCFE: a retrospective study on 53 hips. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015 Nov 18. [Epub ahead of print].

Upasani VV, Matheney TH, Spencer SA, Kim Y-J, Millis MB, Kasser JR. Complications after modified Dunn osteotomy for the treatment of adolescent slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34:661–667.

Velasco R, Schai PA, Exner GU. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a long-term follow-up study after open reduction of the femoral head combined with subcapital wedge resection. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1998;7:43–52.

Wilson PD, Jacobs B, Schecter L. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:1128–1145.

Wylie JD, Beckmann JT, Maak TG, Aoki SK. Arthroscopic treatment of mild to moderate deformity after slipped capital femoral epiphysis: intra-operative findings and functional outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:247–253.

Wyss TF, Clark JM, Weishaupt D, Nötzli HP. Correlation between internal rotation and bony anatomy in the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:152–158.

Zheng G, Tannast M, Anderegg C, Siebenrock KA, Langlotz F. Hip2Norm: an object-oriented cross-platform program for 3D analysis of hip joint morphology using 2D pelvic radiographs. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;87:36–45.

Ziebarth K, Zilkens C, Spencer S, Leunig M, Ganz R, Kim Y-J. Capital realignment for moderate and severe SCFE using a modified Dunn procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:704–716.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Each author certifies that he, or a member of his immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziebarth, K., Milosevic, M., Lerch, T.D. et al. High Survivorship and Little Osteoarthritis at 10-year Followup in SCFE Patients Treated With a Modified Dunn Procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475, 1212–1228 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5252-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5252-6