Abstract

Background

Polyethylene liner dissociation is a rare but catastrophic event in total hip arthroplasty (THA), and certain implant designs are known to be at greater risk. Although the DePuy Pinnacle (Warsaw, IN, USA) modular acetabular construct has an excellent record of fixation and wear, an unexpectedly high number of liner dissociations has been noted.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were (1) to characterize the clinical parameters observed in a large group of patients who have experienced liner dissociations with the DePuy Pinnacle acetabular component; (2) to describe the radiographic findings in this group of patients; and (3) to calculate a minimum frequency of this complication.

Methods

Since 2001, 23 patients with previously well-functioning THAs presented with sudden atraumatic polyethylene liner dissociation at four separate institutions. These THAs were performed between 2001 and 2013. Eight different arthroplasty specialists had performed the index hip arthroplasties using the DePuy Pinnacle acetabular component with a polyethylene liner. Polyethylene failures were evaluated for liner type and radiographic cup position. For three of the surgeons who contributed cases, institutional registries allowed the calculation of the number of components of this type that they used during the period in question, which provided a conservative estimate of the frequency of this type of failure.

Results

All 23 liner failures occurred atraumatically in previously asymptomatic THAs at a mean of 48 months (range, 3–138 months). Patients characteristically reported a new and sudden onset of discomfort with audible, reproducible squeaking. Surgical inspection of dissociated liners demonstrated displacement of polyethylene with shearing of the peripheral locking tabs. Radiographic evaluation demonstrated that 14 cups were well positioned and nine cups were malpositioned outside the so-called safe zone. Conservative estimates of the frequency of this complication from the three surgeons’ practices whose institutional registries allowed calculation of the lowest possible frequency were 0.32% (six of 1888), 0.77% (three of 391), and 0.82% (three of 367).

Conclusions

With this report of 23 additional liner dissociations, we suggest that surgeons should be aware of the problem and take extra precautions when using this implant to ensure locking mechanism integrity at the time of surgery. We caution that the frequency of liner dissociation may be higher than previously reported.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the modular DePuy Pinnacle acetabular component (Warsaw, IN, USA) is commonly used, this implant has been associated with catastrophic polyethylene liner disassociations. The frequency with which this complication occurs is unknown, but to our knowledge, there are 16 reported liner failures in four publications [3, 5, 9, 10], and a 2008 public database described a collection of 41 Pinnacle liner disassociations [8, 10]. In 2013, the National Joint Registry of England and Wales reported a 0.04% polyethylene liner disassociation rate with a 0.01% liner fracture rate in 35,522 hips with a 97% survivorship of metal-on-polyethylene hips and a 98% survivorship of ceramic-on-polyethylene hips. The Australian and American Joint Replacement Registries have reported similar survivorship (Table 1). Although the potential for a catastrophic acetabular locking mechanism and liner disassociation failure exists in all modular acetabular designs, the literature suggests that only the current Pinnacle design and the historic Harris Galante (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) 1 and 2 cups are at greater risk for this unusual complication [2, 16, 19].

In four recent cases of spontaneous disassociation, Gray et al. [3] attributed failure of the Pinnacle to component malposition and exaggerated impingement of the polyethylene in offset, face-changing liners. Two other papers, however, also noted a total of two similar liner disassociations in the absence of these proposed risk factors [9, 10]. The authors could not identify mechanisms of causality but noted that retrieval findings showed a compromised locking mechanism. It has also been suggested that prominent screw heads could contribute to the locking mechanism failure, but many of these cases did not have screw fixation.

We therefore sought to (1) characterize the clinical parameters observed in a large group of patients who have experienced liner dissociations with the DePuy Pinnacle acetabular component; (2) describe the radiographic findings in this group of patients; and (3) to calculate a minimum frequency of this complication.

Materials and Methods

Between 2007 and 2014, eight surgeons treated a total of 25 liner dissociations; one surgeon with two dissociations chose not to participate, leaving 23 locking-mechanism failures available for this retrospective study. These THAs were performed between 2001 and 2014 at four hospitals (Providence Saint John’s Hospital, Santa Monica, CA, USA; Lahey Clinic Foundation, Burlington, MA, USA; Michigan Orthopaedic Center, Lansing, MI, USA; and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA). For three of the surgeons at three of those centers who contributed cases, institutional registries allowed the calculation of the number of components of this type that they used during the period in question, which provided for a conservative estimate of the proportion of patients experiencing this failure (because some patients who were lost to followup may have had the complication, the actual risk could be higher than estimated here).

There were 15 Pinnacle liners with neutral designs and one lipped design, at three hospitals, and the remaining seven liners were +4-mm offset with 10° face-changing geometry at the fourth hospital. Retrieved implants underwent gross visual inspection by the operative surgeons at the time of revision for patterns of wear, impingement, and fracture.

Radiographs were reviewed by the operative surgeon. All cups had adequate radiographs for analyses. Radiographic cup stability was determined by the method of Tompkins et al. [17] and radiographic stem fixation was assessed by the method of Engh et al. [1]. Radiographic cup position was calculated by the method of Lewinnek et al. [6] (Table 2).

Results

Clinical Parameters

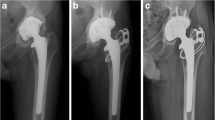

All 23 patients had well-functioning THAs before dissociation. No patients reported trauma or injury before the onset of symptoms. Patients characteristically reported a new and sudden onset of discomfort with audible, reproducible squeaking. The mean time in situ was 48 months (range, 3–138 months). Radiographs consistently demonstrated internal subluxation of the head superiorly within the cup (Fig. 1). Intraoperative findings consistently documented well-fixed acetabular and femoral implants. However, the polyethylene liner often was found to have displaced by rotating away from its original position (Fig. 2), leaving the femoral head prosthesis in direct contact with the inner metal shell of the acetabular cup (Fig. 3).

The femoral head thus articulated with the inner metal shell to create the clunking and squeaking sensation described on presentation by patients. Gross surgical inspection of the liner itself typically demonstrated fracture of the three antirotation locking tabs at the periphery of the polyethylene rim. Soft tissues were found to be without obvious inflammation in all but one hip. This hip demonstrated extensive tissue metallosis after a 3-month delay in revision resulting from medical comorbidities.

Radiographic Findings

All cups and stems were well fixed radiographically according to the methods of Tompkins et al. [8] and Engh et al. [1]. According to the recommendations of Lewinnek et al. [6], 14 cups were well positioned and nine cups were malpositioned outside the so-called safe zone. Well-positioned cups were defined as cups that had both abductions and anteversions within the safe zone. The mean abduction of all 23 cups was 47° (range, 30°–60°) and the mean anteversion was 20° (range, −5° to 35°). The mean abduction of the well-positioned cups was 43° (range, 30°–48°) and the mean anteversion was 21° (range, 13°–25°). Of the nine cups that were well malpositioned, six were overabducted, two were overanteverted, and two were underanteverted. There no malpositioned cups that were underabducted. The mean abduction of the malpositioned cups was 55° (range, 51°–60°). The mean anteversion for the malposition cups that were overanteverted was 38° (range, −35° to 41°). The mean anteversion for the malposition cups that were underanteverted was −2.5° (range, 0° to −5°).

Conservative Estimate of the Frequency of Dissociation

Conservative estimates of the proportion of patients experiencing this complication from the three surgeons’ practices whose institutional registries allowed calculation of the lowest-possible proportions of patients experiencing liner dissociation were 0.32% (six of 1888), 0.77% (three of 391), and 0.82% (three of 367).

Discussion

Finite element analyses suggest a correlation among locking mechanism design, pullout strength, and the risk of liner disassociation. This laboratory finding was historically supported by examining clinical failures of first-generation locking mechanisms in the early Harris Galante 1 (Zimmer) cup [16, 19]. The relatively fragile locking tines and liner-cup mismatch of the Harris Galante cup led to an unusually high number of failures not seen in other designs. Similarly, the DePuy Pinnacle has also demonstrated in the laboratory a pullout strength that is weaker than its prior designs [11, 14, 18]. The clinical correlation of this is now apparent. We report 23 cases of liner dissociation with this acetabular component, and in the practices of three of the surgeons in this series whose institutional registries permitted a conservative estimate of the frequency of this complication, it was between 0.32% and 0.82% (six of 1888 to three of 367).

This study has several important limitations. First, the conservative estimate of the frequency we report is the lowest-possible proportion of patients experiencing this complication, because some patients who were lost to followup may have had the complication treated elsewhere. The actual likelihood of this complication may thus be higher than estimated. Second, surgeon-specific error is possible but seems unlikely with seven different surgeons reporting the problem. Two of the surgeons have since stopped using the device. Surgeons who continue to use the device should be careful to correctly seat the liner, clear soft tissue debris, and check initial liner stability. Alternatively, the liners may have failed for technical reasons. Initial liner malseating or soft tissue interposition at the liner-cup interface may have compromised liner stability. Prominent screw heads have also been implicated as a contributing factor to liner disassociation. However, these are risks for all modular designs, and the high proportion of patients experiencing the complication appears to remain unique to the DePuy Pinnacle acetabular cup.

In the early 2000 s, a series of changes to accommodate a choice of bearing modularity were made to the inner geometry of the new DePuy Pinnacle design [13]. The locking ring and rotation tabs were replaced with a taper-lock mechanism that could accept polyethylene, metal, or ceramic. The outer geometry of the liner changed from an onset design to an inset design with six peripheral locking tabs. Importantly, the nature of the polyethylene also changed. The conventional polyethylene was replaced with a highly crosslinked material irradiated to 50 kGy that improved wear but lowered mechanical strength [4, 15]. This combination of changes to cup geometry, peripheral liner shape, and material strength may be responsible for the relative weakening of the locking mechanism and the correlative increase in reported liner failures. Although a taper-lock mechanism may be sufficient for hard bearings, it may become insufficient for the mechanically softer highly crosslinked polyethylene because it rounds out over time (Fig. 4).

Impingement is likely to be a major factor in mechanical failure. Understandably, Pinnacle liner disassociations are previously reported in cases of cup malposition [3], and indeed malposition may have been a risk factor in nine of these failures. However, component impingement may take place even in well-positioned cups. Although 14 cups in this series were positioned within the so-called safe zone, one prior report found impingement in 60% of well-functioning cups [7], many of which were also well positioned. Thus, the ability to tolerate the mechanical strains of impingement should be built into current designs.

Although all polyethylene liners are subject to impingement, most other designs do not disassociate as frequently. As noted, we report a very conservative estimate of the frequency of liner failure that ranges from 0.32% to 0.82%. The British registry reported a rate of 0.1% for modular DePuy Pinnacle cups [5].

No liner may be able to resist mechanical failure in situations of excessive impingement; however, well-designed cups and locking mechanisms should be able to resist liner disassociation. The manufacturer should consider a design change. The DePuy Duraloc cups improved the strength of the locking mechanism seen in mechanical testing by increasing the polyethylene thickness, adding interior antirotation tabs, and including a Dynamic Locking Ring. Except in one case of locking ring fatigue fracture, no other cases of liner disassociation were identified [12]. If surgical technique is a risk factor for failure, then the design is too technique-sensitive. The cup design should allow for easy insertion without risk of dissociation failure. The manufacturer recommends acetabular revision in cases in which metal-on-metal burnishing is observed, and we believe revision should also be considered when there is acetabular component malposition. Although the benefits of modularity are clear, the locking mechanism and material properties of the liner need to be sufficiently robust to withstand the cyclical strain of impingement. In this study, we report 23 failures of DePuy Pinnacle polyethylene liner dissociations at four separate institutions. We suggest that surgeons should be aware of the problem. We suggest that the frequency of liner dissociation with this implant may be much higher than previously believed. We suggest that all polyethylene Pinnacle liners be tested for locking mechanism integrity at the time of implantation and that visual inspection of the entire rim of the acetabular component should be performed. If screw fixation is used for acetabular shell fixation, the screw heads should be seated below the interface with the plastic shell.

References

Engh CA, Massin P, Suthers KE. Roentgenographic assessment of the biologic fixation of porous-surfaced femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;257:107–128.

González della Valle A, Ruzo PS, Li S, Pellicci P, Sculco TP, Salvati EA. Dislodgment of polyethylene liners in first and second-generation Harris-Galante acetabular components. A report of eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:553–559.

Gray CF, Moore RE, Lee GC. Spontaneous dissociation of offset, face-changing polyethylene liners from the acetabular shell: a report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:841–845.

Harris WH, Muratoglu OK. A review of current cross-linked polyethylenes used in total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;430:46–52.

Jameson SS, Baker PN, Mason J, Rymaszewska M, Gregg PJ, Deehan DJ, Reed MR. Independent predictors of failure up to 7.5 years after 35,386 single-brand cementless total hip replacements: a retrospective cohort study using National Joint Registry data. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:747–757.

Lewinnek GE, Lewis JL, Tarr R, Compere CL, Zimmerman JR. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:217–220.

Malik A, Dorr LD, Long WT. Impingement as a mechanism of dissociation of a Metasul metal-on-metal liner. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:323.e13–16.

MAUDE database. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfMAUDE/search.cfm. Accessed May 28, 2015.

Mayer SW, Wellman SS, Bolognesi MP, Attarian DE. Late liner disassociation of a Pinnacle system acetabular component. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e561–565.

Mesko JW. Acute liner disassociation of a Pinnacle acetabular component. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:815–818.

Postak PD, Ratzel AR, Greenwald AS. Highly crosslinked polyethylene modular acetabular designs: performance characteristics AAOS poster. Available at: http://orl-inc.com. Accessed March 26, 2011.

Powers CC, Fricka KB, Austin MS, Engh CA Sr. Five Duraloc locking ring failures. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1170.e15–18.

Powers CC, Ho H, Beykirch SE, Huynh C, Hopper RH Jr, Engh CA Jr, Engh CA. A comparison of a second- and a third-generation modular cup design: is new improved? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:514–521.

Retpen JB, Solgaard S. Late disassembly of modular acetabular components. A report of two cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:193–195.

Ries MD, Weaver K, Rose RM, Gunther J, Sauer W, Beals N. Fatigue strength of poly-ethylene after sterilization by gamma irradia-tion or ethylene oxide. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;333:87–95.

Saito S, Ryu J, Seki M, Ishii T, Saigo K, Mori S. Analysis and results of dissociation of the polyethylene liner in the Harris-Galante I ace-tabular component. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:522-526.

Tompkins GS, Jacobs JJ, Kull LR, Rosenberg AG, Galante JO. Primary total hip arthroplasty with a porous-coated acetabular component. Seven-to-ten year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:169–176.

Tradonsky S, Postak PD, Froimson AI, Greenwald AS. A comparison of the disassociation strength of modular acetabular components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;296:154–160.

Werle J, Goodman S, Schurman D, Lannin J. Polyethylene liner dissociation in Harris-Galante acetabular components: a report of 7 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:78–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Providence Saint John’s Hospital, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, A., Koli, E.N., Moreland, J. et al. Polyethylene Liner Dissociation Is a Complication of the DePuy Pinnacle Cup: A Report of 23 Cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 474, 441–446 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4396-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4396-5