Abstract

Purpose of the Review

To review what intestinal permeability is and how it is measured, and to summarise the current evidence linking altered intestinal permeability with the development of hypertension.

Recent Findings

Increased gastrointestinal permeability, directly measured in vivo, has been demonstrated in experimental and genetic animal models of hypertension. This is consistent with the passage of microbial substances to the systemic circulation and the activation of inflammatory pathways. Evidence for increased gut permeability in human hypertension has been reliant of a handful of blood biomarkers, with no studies directly measuring gut permeability in hypertensive cohorts. There is emerging literature that some of these putative biomarkers may not accurately reflect permeability of the gastrointestinal tract.

Summary

Data from animal models of hypertension support they have increased gut permeability; however, there is a dearth of conclusive evidence in humans. Future studies are needed that directly measure intestinal permeability in people with hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

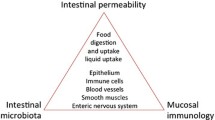

In the last decade, it has emerged that intestinal permeability may be a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases, contributing to inflammatory sequalae and subsequent disease progression [1]. The intestinal wall is lined by a monolayer of epithelial cells that have a crucial role in separating the gut microbiome from the host. When the gut epithelial barrier is disrupted, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other detrimental microbial products enter the host's circulation, leading to the activation of systemic inflammation [2]. Higher inflammatory state is believed to be involved in the development and maintenance of hypertension [3], but many of the mechanisms that start and then maintain this elevated inflammatory state are yet to be determined. Increased permeability of the gut barrier has been observed to occur with a variety of physiological stressors including heat stress [4, 5], exercise stress [6], psychological stress [7], excessive dietary fat intake [8], lack of fibre [9], and sleep deprivation [10] – many of these are also risk factors for hypertension [11, 12]. Here, we review what intestinal permeability is and how it is measured, and the current evidence that links it to the development of experimental and clinical hypertension.

The Gut Epithelium Barrier

The human gastrointestinal tract has a surface area of around 32m2 [13], equivalent to a typical studio apartment. This surface is lined with a single layer of epithelial cells, kept in close proximity by tight junction proteins, adherens junction proteins, and desmosomes [14]. Moreover, goblet cells, specialised cells intercalated with epithelial cells, synthesise and secret the mucin glycoprotein MUC2 as the outermost layer of the intestinal barrier in contact with the gut microbiota [15]. Mucins are the major component of mucus and form a protective layer to the epithelial cells [15]. They serve as a localised niche for some commensal gut microbiota that specialise in binding to and degrading mucin glycans [15]. In healthy conditions, there is a tight balance between the production of and degradation of mucins; however, in unhealthy conditions (e.g., absence of dietary fibres), some of these bacteria can have a high turnover of glycan degradation, degrading the mucus layer and contributing to the breakdown of the epithelial layer in the process [9]. Together, the epithelial cells, intercellular proteins, and mucins form a layer that plays important physical and functional roles in separating the luminal microbiome from the immune cells that inhabit the lamina propria [16]. The intestinal epithelium barrier provides a defence against the entry of harmful substances, such as pathogens and toxins, whilst simultaneously permitting sufficient absorption of nutrients, electrolytes, and water from the gastrointestinal lumen [14]. While the full impacts of a disrupted barrier are still being elucidated, when it is disrupted, immune response pathways are activated in intestinal tissue [9]. Moreover, this could lead to the passage of microbial molecules, such as the bacterial surface LPS, from the intestinal lumen to the systemic circulation, where it could trigger a series of inflammatory responses that contribute to the low-grade chronic inflammation observed in hypertension. While measurement of LPS in healthy individuals is difficult due to its low levels and issues with contaminated lab equipment, inhibition of LPS-receptor, the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), reduces blood pressure (BP) and inflammatory markers (e.g., IL6, macrophage infiltration to the kidneys) in experimental models of hypertension [17, 18]. It is also possible to hypothesise that an impaired gut epithelial barrier will impact the regulation of sodium and water absorption, which could also have an effect on BP.

Permeability of the Gut Barrier

Luminal contents can cross the gastrointestinal epithelium via either transcellular or paracellular mechanisms, depending on molecular size, charge, and hydrophobicity. Molecules may cross transcellularly in a number of mechanisms: 1) passive transport, as is the case for small compounds that may diffuse across the epithelial cell membrane; 2) active transport utilising substrate specific cell surface receptors (e.g., as is the case for monosaccharides and amino acids); and 3) endocytosis, whereby larger peptides and proteins are absorbed via vesicles (Fig. 1). Transcellular endocytosis also appears to be a mechanism by which bacterial components, such as LPS, bacterial extracellular vesicles or even whole bacteria, may cross the gastrointestinal barrier [19••, 20]. In addition to the transcellullar mechanisms described here, molecules may pass via the paracellular route, discussed in further detail below (Fig. 1). The paracellular and the transcellular endocytosis pathways are the most relevant for intestinal permeability, with most research to date focused on the paracellular pathway [21].

Tight junction proteins, adherens junction proteins, and desmosomes facilitate close intercellular contact among the epithelial cells of the intestinal tract. Luminal contents can pass across the epithelial barrier via transcellular passive, active or endocytosis mechanisms, or via paracellular pathway. Intestinal permeability refers to movement of molecules via the transcellular endocytosis or paracellular pathways.

The Paracellular Pathway

Cell-to-cell contact between the epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract is maintained by tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin, zonula occludens-1, and claudin-2), adherens junction proteins (e.g., E-cadherin), and desmosomes. Paracellular permeability is regulated by the tight junction proteins, which determine the size and charge of molecules that are able to pass between the epithelial cells [22]. The intracellular peripheral membrane proteins include the zonula occludens (ZO) family, ZO-1 (also known as tight junction protein-1 [TJP1]), ZO-2, and ZO-3 as well as cingulin, whilst the transmembrane proteins include occludin, tricellulin, and members of the claudin family. There are a total of 27 claudins in mammals, although not all claudins have relevance for the intestinal barrier [19••]. These tight junction proteins permit the paracellular movement of molecules via two different pathways, which have been named the pore or leak pathway.

The pore pathway is defined by claudin proteins which form a charge and size specific channel in the tight junction [23], permitting molecules up to < 8 Å in size to pass between epithelial cells [24]. Thus, a sodium ion, which is positively charged with a size ~ 1 Å, may pass freely through the pore pathway, whilst a glucose molecule (size 9 Å) would be unable. Claudin-2 (CLDN2) and claudin-15 (CLDN15) are the main pore forming claudins expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and both of these claudins form cation specific pores [25, 26], permitting the paracellular transport of sodium ions. The cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-13 and IL-22 have been demonstrated to alter intestinal transcription of CLDN2 [27,28,29,30], although the impact this has on subsequent pore pathway permeability has not been fully elucidated. A possibility is that sodium activation of the immune system and associated produced of these cytokines leads to higher expression of CLDN2, which is associated with higher inflammation in an experimental model of colitis [31]. Moreover, lack of CLDN15 in mice decreased sodium permeability [32]. Considering the intestine is where most of dietary sodium is absorbed, it is plausible to hypothesise that blocking intestinal CLDN2 and CLDN15 may lead to lower sodium uptake and, thus, BP. While no variants in/near these genes have been associated with hypertension in genome-wide association studies, it is possible that these are associated with salt-sensitive hypertension.

The leak pathway is considerably larger, allowing molecules up to 100 Å in size through, with no restrictions on molecular charge [24]. Whilst the specific molecular structure of this pathway is less understood than the pore pathway, it is thought to be regulated by occludin, tricellulin, ZO-1, and perijunctional actomyosin [19••, 33], although there is evidence that alterations in tricellulin expression may affect permeability of this pathway [34]. Myosin light chain kinase splice variant 1 (MLCK1) has been shown to trigger endocytosis of occludin, leading to increased permeability. The expression and activity of MLCK1 can be increased by a number of cytokines including TNF-α [35,36,37] and IL-1β [38], providing evidence for the role of the immune system signalling in affecting paracellular permeability.

In addition to the leak and pore pathways, there is also the unrestricted (or apoptotic) pathway, where severe damage to the gut mucosa results in death of epithelial cells and permits unrestricted paracellular transport of large molecules and bacteria. This epithelial damage and subsequent unrestricted paracellular permeability has been observed in graft vs host disease and gastrointestinal conditions such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis [39], and may play a role after acute cardiovascular events, such as after a stroke, where damage to intestinal epithelial cells is severe [40].

Measuring Intestinal Permeability

Direct measurement of intestinal permeability involves the assessment of a molecule or group of molecules that moves from one side of the intestinal epithelium to the other side. Conversely, indirect measurements investigate biomarkers that are present in collected samples, most commonly blood, that may be utilised for assessment of intestinal permeability.

Ex vivo Measurement

The Ussing chamber technique is a sophisticated method which involves isolating a segment of the gut and mounting it between two halves of a chamber, with each half filled with a physiological solution. The chamber is designed to separate the luminal side from the basolateral side of the epithelium and, to assess permeability, molecules are placed in the luminal chamber, and the flux of these markers to the basolateral side is measured as an indicator of permeability of the epithelium [41]. The size of the molecules selected may permit understanding of the different routes of transport, with molecules such as inulin, polyethylene glycols (PEGs) and Fluorescein Isothiocyanate-Dextran (FITC-Dextran) being utilised for assessment of the paracellular route, whilst larger molecules such as horseradish peroxidase can be utilised for assessment of the transcellular route [21]. The Ussing chamber technique is often utilised in animal studies where intestinal tissues may be obtained following sacrifice of the animals [41, 42] and in human studies of intestinal diseases where endoscopic biopsy samples may be obtained [43]. However, the procurement of endoscopic biopsy samples may prove difficult outside the context of intestinal diseases where endoscopy may be indicated for assessment of disease progression.

In vivo Measurements

Assessment of paracellular permeability is conducted in vivo by assessment of the plasma or urine of orally digested probes. There are many different substances which may be utilised depending on the experimental question being posed, including FITC-Dextran, PEGs, Chromium-51-labeled ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (51CrEDTA), lactulose, mannitol, sucralose and sucrose [21]. The key features for probes is that they must be an adequate size to assess the route of permeability being assessed and freely filtered into urine where they can be measured. The FITC-Dextran permeability test, first described by Tagesson et al. in 1978 [44], is commonly utilized in murine studies due to its relative ease. In this assay, animals are orally gavaged with a solution containing FITC-Dextran (4-kDa), blood is collected and fluorescence measured using a typical laboratory plate reader with fluorescence detection [45]. If a timepoint for blood collection of 1 h post ingestion is selected, the FITC-Dextran assay will represent small intestinal permeability, whilst longer timepoints (4–6 h) will represent whole gut permeability. Animals are dosed according to body weight (usually at 400–600 mg/kg body weight [46,47,48]), though an argument has recently been made for dosing to be conducted according to lean body mass, at least in obese animal models [49]. Whilst this technique can be applied to humans, in practice it is not used, likely related to the costs associated with the dosages required. PEG and 51CrEDTA are both resistant to microbial fermentation in the colon, and, thus, can be utilised for assessment of whole gut permeability [50]. Measurement of intestinal permeability using 51CrEDTA has been utilised in rodent [51] and human studies [52,53,54], however does require the participant to be exposed to a small amount of radiation [55]. Recently, a new protocol using non-radioactive 52Cr-EDTA has been proposed [56].

PEGs span a range of molecular sizes and are assessed in urine by high-pressure liquid chromatography [57]. The assessment of intestinal permeability using PEGs has been shown on have a high agreement with the dual sugar (lactulose/rhamnose) test [58], which is the most popular methodology for assessment of intestinal permeability in humans.

Dual and Multisugar Tests

The most popular in vivo direct measurement of intestinal permeability has been the dual sugar test. In this test, a bolus of monosaccharide (mannitol or L-rhamnose) and disaccharide (lactulose) is consumed orally. In the intestine, the smaller monosaccharides pass through the paracellular pore pathway which permits molecules < 8 Å in size, which the disaccharide cannot pass through [24]. If there is disruption of the tight junction proteins, then these larger molecules can pass through the leak pathway, and the ratio in urine or blood between lactulose and mannitol or L-rhamnose, is used to represent permeability. Urine collected up to 2 h post ingestion is considered to represent exclusively small intestinal permeability [57, 59], although some studies use up to 5–6 h post ingestion to assess small intestinal permeability [60, 61•]. Recently it was suggested that serial plasma measurements (i.e. hourly) may provide greater sensitivity to transient intestinal permeability changes compared with urine collections [5]. Whilst mannitol has traditionally been utilised as the monosaccharide in the dual sugar test, mannitol is present in the regular diet and may, thus, contaminant the results [62]. 13C mannitol and L-rhamnose are alternative monosaccharides that avoid this dietary contamination issue [63]. While useful for measuring small intestinal permeability, lactulose, mannitol and L-rhamnose are all fermented by the gut microbiota when they reach the colon and are thus unreliable for the assessment of specifically colonic permeability.

The small intestine and large intestine (especially the colon) are now recognised to be vastly different anatomically, in terms of physiological functions, pH, and number of bacteria [64]. The permeability difference between these regions is under-appreciated, with the dual sugar tests only assessing small intestinal permeability. A multisugar test has been developed to assess both small intestine and colonic permeability [65, 66]. In this case, monosaccharides (L-rhamnose and erythritol) and disaccharides (lactulose and sucralose) are consumed orally. Permeability in the small intestine is assessed with L-rhamnose and lactulose as per the dual sugar test, whilst in the colon this can be assessed with the non-fermented erythritol and sucralose. Commonly a time period of up to 5 h post-ingestion is considered to represent the small intestine, whilst between 5 to 24 h represents the colon [60, 67]. However, some studies have utilised between 8 and 24 h to represent the colon [68, 69], because there is a large intra-individual variation in small intestinal transit time (from 50–460 min) [70]. Given this wide variation, for studies that want to exclusively assess small intestinal, and not colonic, permeability, it may be prudent to focus on the urine collection of up to 2 h post-ingestion.

Blood Biomarkers of Intestinal Permeability

Whilst the above methods represent direct measurement of molecules that are passing from the luminal side of the gastrointestinal epithelium to the basolateral side for measurement in blood or urine, there is also interest in finding suitable biomarkers for intestinal permeability and many have been proposed. The presence in the blood of LPS, from Gram negative bacteria, has long been considered a clear indicator of intestinal barrier dysfunction [71]. However, there are mounting concerns that the assay used for LPS is not accurate at measuring LPS at lower levels seen in non-septicaemia [72]. Liposaccharide binding protein (LBP) is an endogenous protein produced by the body in response to the presence of LPS, and has been suggested as a more reliable marker [73]. Indeed, a recent study in an obese cohort assessed the correlation between the dual sugar test with six biomarkers (faecal albumin, calprotectin, and zonulin, and plasma intestinal fatty acid binding protein [I-FAPB], LBP and zonulin) [61•]. LBP was the only plasma marker consistently correlated with in vivo permeability measurement in both participants with healthy and higher body weight, showing a variation according to the group studied, from r = 0.423 in those with a healthy body weight up to r = 0.813 in the cohort with obesity [61•]. This shows that LBP may not be a reliable marker for all healthy and disease states.

Disconcertedly, this study found no correlation with two other commonly used gut permeability plasma biomarkers, I-FAPB or zonulin [61•]. I-FAPB is a protein present in differentiated enterocytes, and damage to the epithelial layer results in this protein being released from cells – hence, it is considered an indicator of epithelial damage [74]. Increased I-FAPB has been observed in severe intestinal conditions such as necrotizing enterocolitis [75] and intestinal ischemia [76]. With regards to zonulin, there is mounting evidence that commercially available zonulin ELISA kits are not actually measuring zonulin, but rather other related proteins with unknown function [77, 78]. A recent paper compared zonulin levels with colonic paracellular permeability using Ussing chambers in IBS patients and found no correlation [79]. It has been recommended that studies that assess gut permeability using zonulin measured by these ELISA assays be interpreted with caution.

D-lactate is a byproduct of bacterial carbohydrate fermentation and is minimally produced by human metabolism, with serum levels representing translocation from the gut lumen and thus gut permeability. Serum D-Lactate levels are elevated in Crohn’s disease [80], critically ill patients with gastrointestinal failure [81]. Serum and urinary levels of D-lactate are elevated in diabetes [82], suggesting this marker may be appropriate outside the context of gastrointestinal conditions. Not all bacteria produce D-lactate, with Lactobacilli being the primary D-lactate producers in the human gastrointestinal tract [83]. There is a dearth of evidence as to whether the composition of the gut microbiota and relative abundance of D-Lactate producers affects the reliability of D-Lactate as a marker of gut permeability. Diamine oxidase (DAO) is an enzyme involved in histamine metabolism that is produced by the intestinal mucosa, as well as the kidneys and placenta [84]. Serum DAO levels have been proposed to be a marker of intestinal barrier integrity [85] and is elevated in Crohn’s disease [80]. However, DAO levels are affected by factors such as diet [86], alcohol consumption [87], sex [88], menstrual cycle [89] and pregnancy status [90] which challenge it’s reliability as a biomarker [91]. In summary, more sensitive and accurate markers for intestinal permeability are needed.

Gut Permeability and Hypertension

There is some evidence for alterations in intestinal permeability in hypertension that has been demonstrated in experimental models of hypertension, as well as studies comparing hypertensive and normotensive individuals. As discussed in the previous section, there are different methodologies available for the assessment of intestinal permeability, each with their own benefits and flaws. Overall, the evidence to date, particularly from animal studies (summarised in Table 1), supports the presence of intestinal barrier dysfunction in hypertension. Whether increased gut permeability per se has a causative role in the pathogenesis of hypertension or is a consequence of the disease process remains to be elucidated.

Evidence from Experimental Animal Models of Hypertension

The first published study to investigate gut permeability in animal models of hypertension was Santisteban et al. (2017), who observed increased gut permeability (assessed by the FITC-Dextran assay) in 20 week old, but not 4 week old, spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) relative to age-matched Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats [92]. This suggests that hypertension may be established prior to the increase in intestinal permeability; however, further experiments to pinpoint when this happens exactly are needed to confirm this hypothesis. Shortly after, Jaworska et al. (2017) observed increased gut permeability in a unique assay which assessed the rise in portal vein trimethylamine (TMA, a metabolite produced by the gut microbiota) concentrations following intracolonic TMA infusion in 24–26-week old SHRs relative to age-matched WKY rats [93]. Both studies observed these findings were ameliorated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition. A more recent study in 5-week-old SHRs utilised Ussing chambers for assessing colonic permeability [94]. They noted an increase in paracellular, but not transcellular, permeability [94], which supports alterations in tight junction proteins. Indeed, the levels of several tight junction proteins, measured by Western blots, including occludin and ZO-1 were decreased in hypertensive models in some studies [92, 94], but not others, where differences in colonic occludin or ZO-1 between hypertensive and normotensive animals was not detected when these were assessed by immunofluorescence [93]. Moreover, several studies in the SHR model observed decreased intestinal blood flow [92, 93] and increased intestinal fibrosis [92, 95].

Several studies have also utilised angiotensin II infusion to induce hypertension to assess the effects of hypertension on gut permeability. Rodents infused with angiotensin II had greater gut permeability as assessed by FITC-Dextran [92, 48] and decreased intestinal gene expression of tight junction proteins including ZO-1, particularly on a low fibre diet [48, 96], which was accompanied by increased intestinal expression of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 [96]. Similarly, a study that utilised the DOCA-salt model of hypertension observed increased plasma LPS and decreased colonic gene expression of occludin and ZO-1 [97]. Thus, evidence from experimental animal models has generally supported the presence of increased paracellular permeability in hypertensive models.

Evidence from Human and Non-Human Primates

Kim et al. [48] examined biomarkers of intestinal permeability in a high BP group with a reference group (n = 35) (Table 2). Participants were grouped according to office SBP, irrespective of antihypertensive medication; as such only one-third of the reference group were normotensive, with the remainder having treated hypertension. Similarly, the high BP group contained participants with untreated hypertension, poorly-controlled hypertension, and resistant hypertension. This study found the high BP group had increased plasma levels of I-FAPB, zonulin, and LPS [48]. Similarly, a cross-sectional study in young adults (18–25 years old, n = 96) found those with hypertension had higher serum zonulin levels than normotensive participants [98]. Li et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of 357 gastroenterology inpatient records who had had measurements of serum DAO, LPS, and D-lactate and compared hypertensive to normotensive inpatients, regardless of antihypertensive medication status [99]. This study used cutoffs of ≥ 15, ≥ 20, and ≥ 10 U/L to define elevated levels of DAO, LPS, and D-lactate, respectively, and reported that a greater percentage of hypertensive patients met the criteria for elevated LPS and DAO, but not D-lactate, compared to normotensive patients.

Tomsett et al. compared women who proceeded to develop hypertension during pregnancy, including pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension, with those that remained normotensive throughout pregnancy (n = 55) [100]. There was no difference in serum zonulin levels at 16-weeks of gestation, though at 28-weeks of gestation those who would become hypertensive had higher levels compared with normotensive women [100]. Similarly, a small study comparing 13 women with pre-eclampsia with 13 age-matched normotensive pregnant women showed that the women with pre-eclampsia had elevated LBP levels during hospital admission for parturition [101]. Paradoxically, a recent cross-sectional case control study comparing women with pre-eclampsia to healthy pregnant women at an obstetric visit during the third trimester observed that plasma LBP and zonulin levels were decreased in the women with pre-eclampsia compared with healthy controls (n = 44) [102]. There is conflicting evidence regarding intestinal permeability changes during pregnancy and hypertension.

One other interesting and relevant study to this discussion was undertaken in non-human primates. Vemuri et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in 153 vervet monkeys, and observed that LBP levels were correlated with both systolic and diastolic BP readings [103•]. In a second study by this group, 16 adult rhesus monkeys were assessed for hypertensive status using cutoffs for systolic and diastolic BP of 120 mm Hg and 80 mm Hg, respectively, a protocol that is suitable for use in non-human primates [104]. Hypertensive rhesus monkeys had higher LBP levels than normotensive rhesus monkeys at baseline, with LBP levels progressively elevating in the hypertensive group over the course of the study [103•]. This study was the first longitudinal assessment of a marker of intestinal permeability in non-human primates or humans and provides the first evidence that intestinal permeability does increase over time in the context of hypertension.

Intestinal Permeability and Hypertension: The Chicken and Egg Question

A key question that remains is if hypertension leads to increased internal permeability, or if intestinal permeability, caused by other factors such as low fibre intake, gut dysbiosis, medication or comorbidities such as obesity, activates inflammatory processes that contribute to the development of hypertension. In the latter option, as BP increases, it could then damage the intestinal epithelium and further exacerbate permeability, and thus, BP. If intestinal permeability is indeed present in hypertension and involved in its pathophysiological mechanisms, another important question is if BP and its associated end-organ damage could be lowered by a reduction in intestinal permeability. For example, studies in mice using gut microbial metabolites that restore intestinal barrier function and reduce inflammatory cytokines also resulted in lower BP [96]. Whether this also happens in hypertensive patients is yet to be determined. A key limitation in the field is that only blood and faecal samples are available, and, as discussed above, the current biomarkers for intestinal permeability are not reliable enough to answer this question.

Conclusion

Evidence from animal models has clearly demonstrated that there is increased gut permeability, assessed by direct measurement, in experimental models of hypertension. Evidence within human hypertension is limited, with several indirect biomarkers that are purported to be indicators of gut permeability increased in participants with hypertension. However, the reliability of these biomarkers is questionable. Whether hypertension leads to increased gut permeability, or vice-versa, has not been clearly established. It is possible that there is a bidirectional link between the two rather than a causal one-way relationship. A greater understanding of the role of gut permeability in the pathogenesis of hypertension may benefit targeted treatments to prevent and delay the scourge of elevated BP.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, Ockhuizen T, Schulzke J-D, Serino M, et al. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7.

Snelson M, Tan S, Clarke R, de Pasquale C, Thallas-Bonke V, Nguyen T, et al. Processed Foods drive Intestinal Barrier permeability and Microvascular Diseases. Sci Adv. 2021;7(14). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe4841.

Guzik TJ, Nosalski R, Maffia P, Drummond GR. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-023-00964-1.

Koch F, Thom U, Albrecht E, Weikard R, Nolte W, Kuhla B, et al. Heat stress directly impairs gut integrity and recruits distinct immune cell populations into the bovine intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(21):10333–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820130116.

Houghton MJ, Snipe RMJ, Williamson G, Costa RJS. Plasma measurements of the dual sugar test reveal carbohydrate immediately alleviates intestinal permeability caused by exertional heat stress. J Physiol. 2023;601(20):4573–89. https://doi.org/10.1113/jp284536.

Keirns BH, Koemel NA, Sciarrillo CM, Anderson KL, Emerson SR. Exercise and intestinal permeability: another form of exercise-induced hormesis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020;319(4):G512–8. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00232.2020.

Vanuytsel T, van Wanrooy S, Vanheel H, Vanormelingen C, Verschueren S, Houben E, et al. Psychological stress and corticotropin-releasing hormone increase intestinal permeability in humans by a mast cell-dependent mechanism. Gut. 2014;63(8):1293–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305690.

Rohr MW, Narasimhulu CA, Rudeski-Rohr TA, Parthasarathy S. Negative Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Permeability: A Review. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(1):77–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz061.

Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, et al. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167(5):1339–53 e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043.

Wang Z, Chen W-H, Li S-X, He Z-M, Zhu W-L, Ji Y-B, et al. Gut microbiota modulates the inflammatory response and cognitive impairment induced by sleep deprivation. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(11):6277–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01113-1.

Cuffee Y, Ogedegbe C, Williams NJ, Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A. Psychosocial risk factors for hypertension: an update of the literature. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(10):483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-014-0483-3.

Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(4):223–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2.

Helander HF, Fändriks L. Surface area of the digestive tract - revisited. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(6):681–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2014.898326.

Buckley A, Turner JR. Cell Biology of Tight Junction Barrier Regulation and Mucosal Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10(1). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a029314.

Luis AS, Hansson GC. Intestinal mucus and their glycans: A habitat for thriving microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31(7):1087–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.05.026.

Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336(6086):1268–73. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1223490.

Bomfim GF, Dos Santos RA, Oliveira MA, Giachini FR, Akamine EH, Tostes RC, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to blood pressure regulation and vascular contraction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond). 2012;122(11):535–43. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20110523.

Muralitharan RR, Zheng T, Dinakis E, Xie L, Barbaro-Wahl A, Jama HA, et al. GPR41/43 regulates blood pressure by improving gut epithelial barrier integrity to prevent TLR4 activation and renal inflammation. bioRxiv. 2023:2023.03.20.533376. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.20.533376.

•• Horowitz A, Chanez-Paredes SD, Haest X, Turner JR. Paracellular permeability and tight junction regulation in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(7):417–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00766-3. This review provides in-depth details of the molecular mechanisms by which paracellular permeability is regulated, with relevance to disease conditions of the gastrointestinal tract.

O’Donoghue EJ, Krachler AM. Mechanisms of outer membrane vesicle entry into host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18(11):1508–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12655.

Vanuytsel T, Tack J, Farre R. The Role of Intestinal Permeability in Gastrointestinal Disorders and Current Methods of Evaluation. Front Nutr. 2021;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.717925.

Campbell HK, Maiers JL, DeMali KA. Interplay between tight junctions & adherens junctions. Exp Cell Res. 2017;358(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.03.061.

Günzel D. Claudins: vital partners in transcellular and paracellular transport coupling. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-016-1909-3.

Zuo L, Kuo W-T, Turner JR. Tight Junctions as Targets and Effectors of Mucosal Immune Homeostasis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;10(2):327–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.001.

Wada M, Tamura A, Takahashi N, Tsukita S. Loss of claudins 2 and 15 from mice causes defects in paracellular Na+ flow and nutrient transport in gut and leads to death from malnutrition. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(2):369–80. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.035.

Holmes JL, Van Itallie CM, Rasmussen JE, Anderson JM. Claudin profiling in the mouse during postnatal intestinal development and along the gastrointestinal tract reveals complex expression patterns. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6(6):581–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.modgep.2005.12.001.

Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Su L, Shen L, Sullivan EA, Wang Y, et al. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase activation induces mucosal interleukin-13 expression to alter tight junction ion selectivity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(16):12037–46. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.064808.

Tsai PY, Zhang B, He WQ, Zha JM, Odenwald MA, Singh G, et al. IL-22 Upregulates Epithelial Claudin-2 to Drive Diarrhea and Enteric Pathogen Clearance. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(6):671–81.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.009.

Suzuki T, Yoshinaga N, Tanabe S. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) regulates claudin-2 expression and tight junction permeability in intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(36):31263–71. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.238147.

Yamamoto T, Kojima T, Murata M, Takano K, Go M, Chiba H, et al. IL-1beta regulates expression of Cx32, occludin, and claudin-2 of rat hepatocytes via distinct signal transduction pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2004;299(2):427–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.06.011.

Raju P, Shashikanth N, Tsai PY, Pongkorpsakol P, Chanez-Paredes S, Steinhagen PR, et al. Inactivation of paracellular cation-selective claudin-2 channels attenuates immune-mediated experimental colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(10):5197–208. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI138697.

Hempstock W, Nagata N, Ishizuka N, Hayashi H. The effect of claudin-15 deletion on cationic selectivity and transport in paracellular pathways of the cecum and large intestine. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6799. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33431-5.

Buschmann MM, Shen L, Rajapakse H, Raleigh DR, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. Occludin OCEL-domain interactions are required for maintenance and regulation of the tight junction barrier to macromolecular flux. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(19):3056–68. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0688.

Saito AC, Higashi T, Fukazawa Y, Otani T, Tauchi M, Higashi AY, et al. Occludin and tricellulin facilitate formation of anastomosing tight-junction strand network to improve barrier function. Mol Biol Cell. 2021;32(8):722–38. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E20-07-0464.

Graham WV, Wang F, Clayburgh DR, Cheng JX, Yoon B, Wang Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-induced long myosin light chain kinase transcription is regulated by differentiation-dependent signaling events. Characterization of the human long myosin light chain kinase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(36):26205–15. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M602164200.

Ye D, Ma I, Ma TY. Molecular mechanism of tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(3):G496–504. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2005.

Wang F, Graham WV, Wang Y, Witkowski ED, Schwarz BT, Turner JR. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(2):409–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62264-x.

Kaminsky LW, Al-Sadi R, Ma TY. IL-1β and the Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Barrier. Front Immunol. 2021;12:767456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.767456.

Nalle SC, Turner JR. Intestinal barrier loss as a critical pathogenic link between inflammatory bowel disease and graft-versus-host disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8(4):720–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2015.40.

Peh A, O’Donnell JA, Broughton BRS, Marques FZ. Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Stroke: A Double-Edged Sword. Stroke. 2022;53(5):1788–801. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036800.

Thomson A, Smart K, Somerville MS, Lauder SN, Appanna G, Horwood J, et al. The Ussing chamber system for measuring intestinal permeability in health and disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-1002-4.

Clarke LL. A guide to Ussing chamber studies of mouse intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296(6):G1151–66. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.90649.2008.

Vanheel H, Vicario M, Vanuytsel T, Oudenhove LV, Martinez C, Keita ÅV, et al. Impaired duodenal mucosal integrity and low-grade inflammation in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2014;63(2):262–71. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303857.

Tagesson C, Sjödahl R, Thorén B. Passage of Molecules through the Wall of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13(5):519–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365527809181758.

Snelson M, Tan SM, Higgins GC, Lindblom RSJ, Coughlan MT. Exploring the role of the metabolite-sensing receptor GPR109a in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;318(3):F835–42. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00505.2019.

Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, et al. Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Metabolic Endotoxemia-Induced Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Diabetes in Mice. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1470–81. https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-1403.

Cani PD, Possemiers S, Van de Wiele T, Guiot Y, Everard A, Rottier O, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut. 2009;58(8):1091–103. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2008.165886.

Kim S, Goel R, Kumar A, Qi Y, Lobaton G, Hosaka K et al. Imbalance of gut microbiome and intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in patients with high blood pressure. Clinical science (London, England : 1979). 2018;132(6):701–18. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20180087.

Voetmann LM, Rolin B, Kirk RK, Pyke C, Hansen AK. The intestinal permeability marker FITC-dextran 4kDa should be dosed according to lean body mass in obese mice. Nutr Diabetes. 2023;13(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-022-00230-2.

Bjarnason I, Macpherson A, Hollander D. Intestinal permeability: An overview. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(5):1566–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(95)90708-4.

Ten Bruggencate SJM, Bovee-Oudenhoven IMJ, Lettink-Wissink MLG, Van der Meer R. Dietary Fructooligosaccharides Increase Intestinal Permeability in Rats. J Nutr. 2005;135(4):837–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/135.4.837.

Ten Bruggencate SJM, Bovee-Oudenhoven IMJ, Lettink-Wissink MLG, Katan MB, van der Meer R. Dietary Fructooligosaccharides Affect Intestinal Barrier Function in Healthy Men. J Nutr. 2006;136(1):70–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.1.70.

Ainsworth M, Eriksen J, Rasmussen JW, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Intestinal permeability of 51Cr-labelled ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in patients with Crohn's disease and their healthy relatives. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24(8):993–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365528909089246.

Arslan G, Atasever T, Cindoruk M, Yildirim IS. (51)CrEDTA colonic permeability and therapy response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22(9):997–1001. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006231-200109000-00009.

Horton F, Wright J, Smith L, Hinton PJ, Robertson MD. Increased intestinal permeability to oral chromium (51Cr) -EDTA in human Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2014;31(5):559–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12360.

von Martels JZH, Bourgonje AR, Harmsen HJM, Faber KN, Dijkstra G. Assessing intestinal permeability in Crohn’s disease patients using orally administered 52Cr-EDTA. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211973. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211973.

Camilleri M. What is the leaky gut? Clinical considerations in humans. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2021;24(5):473–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000778.

van Wijck K, Bessems BA, van Eijk HM, Buurman WA, Dejong CH, Lenaerts K. Polyethylene glycol versus dual sugar assay for gastrointestinal permeability analysis: is it time to choose? Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2012;5:139–50. https://doi.org/10.2147/ceg.S31799.

Seikrit C, Schimpf JI, Wied S, Stamellou E, Izcue A, Pabst O, et al. Intestinal permeability in patients with IgA nephropathy and other glomerular diseases: an observational study. J Nephrol. 2023;36(2):463–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01454-2.

Wilms E, Jonkers D, Savelkoul HFJ, Elizalde M, Tischmann L, de Vos P, et al. The Impact of Pectin Supplementation on Intestinal Barrier Function in Healthy Young Adults and Healthy Elderly. Nutrients. 2019;11(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071554.

• Seethaler B, Basrai M, Neyrinck AM, Nazare JA, Walter J, Delzenne NM, et al. Biomarkers for assessment of intestinal permeability in clinical practice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(1):G11-g7. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00113.2021.

Grover M, Camilleri M, Hines J, Burton D, Ryks M, Wadhwa A, et al. (13) C mannitol as a novel biomarker for measurement of intestinal permeability. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(7):1114–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12802.

Khoshbin K, Khanna L, Maselli D, Atieh J, Breen-Lyles M, Arndt K, et al. Development and Validation of Test for “Leaky Gut”; Small Intestinal and Colonic Permeability Using Sugars in Healthy Adults. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(2):463–75.e13. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.020.

McCallum G, Tropini C. The gut microbiota and its biogeography. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00969-0.

van Wijck K, van Eijk HMH, Buurman WA, Dejong CHC, Lenaerts K. Novel analytical approach to a multi-sugar whole gut permeability assay. J Chromatogr B. 2011;879(26):2794–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.08.002.

Tatucu-Babet OA, Forsyth A, Udy A, Radcliffe J, Benheim D, Calkin C, et al. Use of a sensitive multisugar test for measuring segmental intestinal permeability in critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults: A pilot study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(2):454–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpen.2110.

Cao S, Shaw EL, Quarles WR, Sasaki GY, Dey P, Hodges JK et al. Daily Inclusion of Resistant Starch-Containing Potatoes in a Dietary Guidelines for Americans Dietary Pattern Does Not Adversely Affect Cardiometabolic Risk or Intestinal Permeability in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2022;14(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081545.

Rao AS, Camilleri M, Eckert DJ, Busciglio I, Burton DD, Ryks M, et al. Urine sugars for in vivo gut permeability: validation and comparisons in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea and controls. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301(5):G919–28. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00168.2011.

Camilleri M, Nadeau A, Lamsam J, Nord SL, Ryks M, Burton D, et al. Understanding measurements of intestinal permeability in healthy humans with urine lactulose and mannitol excretion. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(1):e15–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01361.x.

Fischer M, Fadda HM. The Effect of Sex and Age on Small Intestinal Transit Times in Humans. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105(2):682–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.24619.

Snelson M, de Pasquale C, Ekinci EI, Coughlan MT. Gut microbiome, prebiotics, intestinal permeability and diabetes complications. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35(3):101507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2021.101507.

Pearce K, Estanislao D, Fareed S, Tremellen K. Metabolic Endotoxemia, Feeding Studies and the Use of the Limulus Amebocyte (LAL) Assay; Is It Fit for Purpose? Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10060428.

Schumann RR, Leong SR, Flaggs GW, Gray PW, Wright SD, Mathison JC, et al. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Science. 1990;249(4975):1429–31. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2402637.

Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, MacDonald TT, Troost F, Cani PD, et al. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312(3):G171–93. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2015.

Heida FH, Hulscher JB, Schurink M, Timmer A, Kooi EM, Bos AF, et al. Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein levels in Necrotizing Enterocolitis correlate with extent of necrotic bowel: results from a multicenter study. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(7):1115–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.11.037.

Ding CM, Wu YH, Liu XF. Diagnostic Accuracy of Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein for Acute Intestinal Ischemia: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Lab. 2020;66(6). https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.191139.

Ajamian M, Steer D, Rosella G, Gibson PR. Serum zonulin as a marker of intestinal mucosal barrier function: May not be what it seems. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210728.

Scheffler L, Crane A, Heyne H, Tönjes A, Schleinitz D, Ihling CH, et al. Widely Used Commercial ELISA Does Not Detect Precursor of Haptoglobin2, but Recognizes Properdin as a Potential Second Member of the Zonulin Family. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00022.

Meira de-Faria F, Bednarska O, Ström M, Söderholm JD, Walter SA, Keita ÅV. Colonic paracellular permeability and circulating zonulin-related proteins. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(4):424–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2021.1879247.

Cai J, Chen H, Weng M, Jiang S, Gao J. Diagnostic and Clinical Significance of Serum Levels of D-Lactate and Diamine Oxidase in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Gastroent Res Pract. 2019;2019:8536952. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8536952.

Teng J, Xiang L, Long H, Gao C, Lei L, Zhang Y. The Serum Citrulline and D-Lactate are Associated with Gastrointestinal Dysfunction and Failure in Critically Ill Patients. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:4125–34. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S305209.

Talasniemi JP, Pennanen S, Savolainen H, Niskanen L, Liesivuori J. Analytical investigation: Assay of D-lactate in diabetic plasma and urine. Clin Biochem. 2008;41(13):1099–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.06.011.

Remund B, Yilmaz B, Sokollik C. D-Lactate: Implications for Gastrointestinal Diseases. Children (Basel). 2023;10(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060945.

Elmore BO, Bollinger JA, Dooley DM. Human kidney diamine oxidase: heterologous expression, purification, and characterization. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7(6):565–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00775-001-0331-1.

Zhou S, Xu C-D, Chen S-N, Liu W. [Correlation of intestinal mucosal injury with serum diamine oxidase]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2006;44(2):93–5.

Miyoshi M, Ueno M, Matsuo M, Hamada Y, Takahashi M, Yamamoto M, et al. Effect of dietary fatty acid and micronutrient intake/energy ratio on serum diamine oxidase activity in healthy women. Nutrition. 2017;39–40:67–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2017.03.004.

Sessa A, Desiderio MA, Perin A. Effect of Acute Ethanol Administration on Diamine Oxidase Activity in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract of Rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1984;8(2):185–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05835.x.

García-Martín E, Ayuso P, Martínez C, Agúndez JAG. Improved analytical sensitivity reveals the occurrence of gender-related variability in diamine oxidase enzyme activity in healthy individuals. Clin Biochem. 2007;40(16):1339–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.07.019.

Hamada Y, Shinohara Y, Yano M, Yamamoto M, Yoshio M, Satake K, et al. Effect of the menstrual cycle on serum diamine oxidase levels in healthy women. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(1):99–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.10.013.

Brew OB, Sullivan MHF. Localisation of mRNAs for diamine oxidase and histamine receptors H1 and H2, at the feto-maternal interface of human pregnancy. Inflamm Res. 2001;50(9):449–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00000269.

Tan Z, Ou Y, Cai W, Zheng Y, Li H, Mao Y, et al. Advances in the Clinical Application of Histamine and Diamine Oxidase (DAO) Activity: A Review. Catalysts. 2023;13(1):48.

Santisteban MM, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, Kim S, Yang T, Shenoy V, et al. Hypertension-Linked Pathophysiological Alterations in the Gut. Circ Res. 2017;120(2):312–23. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.309006.

Jaworska K, Huc T, Samborowska E, Dobrowolski L, Bielinska K, Gawlak M, et al. Hypertension in rats is associated with an increased permeability of the colon to TMA, a gut bacteria metabolite. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189310. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189310.

Wang T, Gao L, Yang Z, Wang F, Guo Y, Wang B, et al. Restraint Stress in Hypertensive Rats Activates the Intestinal Macrophages and Reduces Intestinal Barrier Accompanied by Intestinal Flora Dysbiosis. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:1085–110. https://doi.org/10.2147/jir.S294630.

Stewart DC, Rubiano A, Santisteban MM, Shenoy V, Qi Y, Pepine CJ, et al. Hypertension-linked mechanical changes of rat gut. Acta Biomater. 2016;45:296–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.08.045.

Kaye DM, Shihata W, Jama HA, Tsyganov K, Ziemann M, Kiriazis H et al. Deficiency of Prebiotic Fibre and Insufficient Signalling Through Gut Metabolite Sensing Receptors Leads to Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2020:In press. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043081.

Robles-Vera I, de la Visitación N, Sánchez M, Gómez-Guzmán M, Jiménez R, Moleón J, et al. Mycophenolate Improves Brain-Gut Axis Inducing Remodeling of Gut Microbiota in DOCA-Salt Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121199.

Ntlahla EE, Mfengu MM, Engwa GA, Nkeh-Chungag BN, Sewani-Rusike CR. Gut permeability is associated with hypertension and measures of obesity but not with Endothelial Dysfunction in South African youth. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(3):1172–84.

Li C, Xiao P, Lin D, Zhong H-J, Zhang R, Zhao Z-G, et al. Risk Factors for Intestinal Barrier Impairment in Patients With Essential Hypertension. Front Med. 2021;7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.543698.

Tomsett KI, Barrett HL, Dekker EE, Callaway LK, McIntyre DH, Dekker NM. Dietary Fiber Intake Alters Gut Microbiota Composition but Does Not Improve Gut Wall Barrier Function in Women with Future Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3862.

Wang Y, Walli AK, Schulze A, Blessing F, Fraunberger P, Thaler C, et al. Heparin-mediated extracorporeal low density lipoprotein precipitation as a possible therapeutic approach in preeclampsia. Transfus Apheres Sci. 2006;35(2):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2006.05.010.

Mutluoglu G, Yay T, Gülsever AB, Madenci ÖC, Kaptanagasi AO. The Evaluation of Intestinal Permeability in Preeclamptic Pregnancy. Mater Sociomed. 2023;35(1):48–52. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2023.35.48-52.

• Vemuri R, Ruggiero A, Whitfield JM, Dugan GO, Cline JM, Block MR, et al. Hypertension promotes microbial translocation and dysbiotic shifts in the fecal microbiome of nonhuman primates. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;322(3):H474–85. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00530.2021. This study in non-human primates provides longitudinal evidence over 2 years that intestinal permeability progressively increases in the context of hypertension.

Brownlee RD, Kass PH, Sammak RL. Blood Pressure Reference Intervals for Ketamine-sedated Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2020;59(1):24–9. https://doi.org/10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-19-000072.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions F.Z.M. is supported by a Senior Medical Research Fellowship from the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation, a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (105663), and a National Health & Medical Research Council Emerging Leader Fellowship (GNT2017382). T.V. is supported by a senior clinical research fellowship (1830517N) of the Flanders Research Foundation (FWO Vlaanderen). M.S. is supported by a National Heart Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (106698).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and FZM conceptualized the manuscript. MS wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Figure 1. FZM and TV edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Snelson, M., Vanuytsel, T. & Marques, F.Z. Breaking the Barrier: The Role of Gut Epithelial Permeability in the Pathogenesis of Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-024-01307-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-024-01307-2