Abstract

Experimental studies on the effect of prior conviction evidence (PCE) on judgments of guilt are conflicting, ranging from an increase of guilt to a decrease of guilt, depending on certain boundary conditions. The overall effect of PCE seems to be small and likely depends on moderators. Due to small samples or because of lack of experimental manipulations, these moderators could not yet be meta-analyzed. This literature review follows up on these moderators with the aim to provide a clearer understanding under which circumstances PCE could harm or benefit the defendant, or when prior convictions of the defendant are completely irrelevant. Existing literature on PCE was reviewed to identify potential moderators and to provide directions for future research. Identified moderators were categorized into PCE characteristics (similarity and seriousness of PCE, PCE quantity, admissibility, and limiting instructions), case characteristics (ambiguity, seriousness of current offense), and methodological moderators (salience, control condition and manipulation checks, sample, individual vs. group decisions, richness of stimulus materials). PCE effects seem to depend on various factors that greatly narrow the influence of PCE. Therefore, an integrative perspective is proposed for future studies that take legal decision-making theories and information processing theories into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Is a defendant with a criminal record convicted more often than a defendant without any prior convictions? In the USA, Great Britain, and other countries using adversarial legal systems, the prior record is usually kept from the jury in order to not bias them against the defendant (e.g., Hans and Doob 1976). If the jury does find out about it (e.g., because somebody mentions it during the trial), jurors are instructed by the judge to use this information only for the evaluation of the defendant’s credibility, but not to determine the defendant’s guilt (Rule 609, Federal Rules of Evidence, USA). In England and Wales, information about a prior record can be used to (dis)proof the defendant’s good character since the Criminal Justice Act (2003), but if it appears to the court that the admission of PCE would have an adverse effect on the fairness of the proceedings, it can be excluded.

A case analysis of over 300 criminal trails (USA) indicates that if defendants with a criminal record decide to testify, the jury finds out about the defendant’s prior record half of the time (Eisenberg and Hans 2009, see also Laudan and Allen 2011). This poses a conundrum for defendants with prior records: If they chose to not testify, they can be accused of hiding something (e.g., Clary and Shaffer 1980; Shaffer and Case 1982) and be met with more skepticism (Jones and Harrison 2009). If they do testify, there is 50% chance that the jury finds out about the prior conviction, which could bias the jurors against them. However, it is still unclear if prior convictions actually have such a negative impact. Overall, empirical results on the effect of prior conviction evidence (PCE) are mixed. Some studies indicated that PCE increases the likelihood of guilt and convictions (e.g., Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Greene and Dodge 1995; Pickel 1995; Wissler and Saks 1985), mediated by judgments of the defendant’s criminal propensity (Feather and Souter 2002; Greene and Dodge 1995; Lloyd-Bostock 2000; Otto et al. 1994). However, other studies found no effect of PCE (e.g., Clary and Shaffer 1980; Honess and Mathews 2012; Oswald 2009) or limited the effect of PCE to boundary conditions (e.g., Cowley and Colyer 2010; Hans and Doob 1976).

In legal systems without a jury, for instance in continental European countries, decision-makers (mainly professional judges or panels of professional judges and lay judges) have access to all available information, including prior convictions of the defendant. Because of judges’ training and education, it is expected of them that they are capable to use PCE for sentencing purposes only,Footnote 1 but not for the verdict (Oswald 2009; Schlotthauser and Yundina 2016). Studies done in Switzerland (Oswald 2009) and Austria (Schmittat et al. 2022) conducted with (advanced) law students also did not find a consistent PCE effect; thus, it remains unclear if legal training improves the cognitive compliance to not use PCE for certain judgments.

Many legal procedures therefore define how and under which circumstances the criminal history of a defendant is allowed to enter the decision-making process, whilst assuming that the decision-maker (jurors, lay, or professional judges) can freely chose to ignore information for one decision but use it at for another decision. This legal assumption clearly clashes with the results of experimental psychological studies on inadmissible evidence (e.g., meta-analysis by Steblay et al. 2006). However, before this discrepancy between legal procedures and psychological mechanisms can be addressed, it should be evaluated whether PCE even has any negative effect on the verdict (see also Laudan and Allen 2011), thus if the limited use of PCE is even warranted. A meta-analysis about the influence of various juror and defendant characteristics on legal decision-making analyzed 19 individual samples investigating the effect of PCE. There was only a modest effect of PCE (r = 0.12). The authors noted that this effect likely depends on other variables and they identified similarity of the crime and salience of PCE as potential moderators (Devine and Caughlin 2014). Since similarity was only manipulated by a few studies and salience had not been systematically studied at all, the authors were unable to examine them as moderators in their meta-analysis.

The present literature review follows up on these moderators, including recent experimental studies (Schmittat et al. 2022) and studies which were not included in the meta-analysis (e.g., Clary and Shaffe 1980, 1985; Oswald 2009; Pickel 1995). A closer look at the used study materials and applied methodology might provide a clearer understanding under which circumstances PCE could harm or even benefit the defendant, and when PCE might be completely irrelevant.

Method

Literature searches were first and foremost conducted by the author and a research assistant on the databases PsycINFO, HeinOnline, Google Scholar, and SocINDEX with “prior record,” “prior conviction,” “prior acquittal,” “prior conviction evidence,” “PCE,” “prior criminal history,” “criminal history + verdict,” “criminal history + guilt,” and “witness impeachment + verdict” as keywords. The focus was put on published experimental studies that manipulated PCE and recorded some type of guilt judgment (verdict, guilt probability/likelihood). Studies that solely investigated the influence of PCE on sentencing were excluded, because PCE may legally be used for sentencing purposes. Furthermore, case studies and record analyses were also excluded in order to study potential moderators that were manipulated in a controlled experimental environment. Studies that investigated witness impeachment through PCE were excluded as well, since the research question was about the potentially damaging (or irrelevant) impact of the defendant’s criminal history (not of a witness’ prior conviction of perjury) on the verdict in a current case. By examining the reference lists of the identified articles, additional publications were located, resulting in a total of 28 individual samples (see Table 1). All studies were analyzed with regard to PCE manipulations and investigated interactions with other factors, but also included exploratory examination of chosen stimulus materials and methodology that were not the primary focus of the original studies (statistical significance and effect sizes can therefore not be reported). Potential moderators that could explain the divergent effects of PCE were identified. These moderators are categorized into PCE characteristics (similarity and seriousness, PCE quantity, admissibility), case characteristics (ambiguity, seriousness of current offense), and methodological moderators (salience, sample, stimulus richness). Implications for future research are discussed.

PCE Characteristics

Similarity and Seriousness of PCE

As noted by Devine and Caughlin (2014), similarity between PCE and current offense is an obvious moderator and represents the moderator that most often has been studied systematically (e.g., Allison and Brimacombe 2010; Clary and Shaffer 1985; Lloyd-Bostock 2000, 2006; Oswald 2009). The majority of the other studies used either only similar PCE (e.g., Cowley and Colyer 2010; Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Honess and Mathews 2012; Schmittat et al. 2022, study 1), or dissimilar PCE (Pickel 1995), or left some room for interpretation on how similar the two offenses actually are (Edwards and Bryan 1997; Greene and Dodge 1995; Schmittat et al. 2022, study 2) prompting the question if PCE and current offense need to be identical (e.g., both for stealing car radios; Schmittat et al. 2022) or simply from the same category (e.g., bank robbery vs. home break-in; Greene and Dodge 1995).

Early studies found that a similar prior conviction increases guilt judgments, whereas dissimilar prior conviction does not (Sealy and Cornish 1973)Footnote 2. This was further supported by Wissler and Saks (1985) and Allison and Brimacombe (2010). Perjury as PCE (also a dissimilar PCE), which should provide the most valid information about the defendant’s credibility or character for which PCE can explicitly be used, led to comparable conviction rates as dissimilar PCE (Wissler and Saks 1985) or was not significantly different from either similar or dissimilar PCE (Allison and Brimacombe 2010). In Clary and Shaffer (1985), similarity was only a relevant factor in combination with pleading the 5th amendment (thereby appearing to withholding evidence) and only after jury deliberation. Seriousness of PCE did not matter statistically in Wissler and Saks (1985).

Lloyd-Bostock (2000) added recency (18 months vs. 5 years ago) of similar/dissimilar PCE as a factor (see also Lloyd-Bostock 2006). Results indicate that a recent similar PCE significantly increased guilt ratings compared to any other variation of PCE (recent dissimilar, old dissimilar, no information about PCE, no prior record, old similar). After deliberation, a recent dissimilar PCE even led to significantly lower guilt ratings compared to the “no information about the defendant’s criminal history” and “no PCE” conditions. Thus, whereas recent similar PCE can increase guilt ratings of the current charge, recent dissimilar PCE can work in the defendant’s advantage, because jurors might hold the beliefs that offenders commit similar offenses in the future, but are less likely to commit other offenses (Howe 1991). One exception is a prior conviction for indecent assault on a child, because this type of PCE trumped any effect of similarity (Lloyd-Bostock 2000) and created the greatest prejudice against the defendant (e.g., Cowley and Colyer 2010).

Therefore, there seems to be some experimental evidence that similarity is an important moderator for the effect of PCE. Yet, the effect of similarity is not consistent: Jones and Harrison (2009) found no significant similarity effect, but the reported statistical analysis focused on similarity in combination with the defendant’s choice to testify. No information is available on the main effects of PCE or similarity. On a descriptive level, a similar prior record led to the highest guilt ratings (M = 6.58, SD = 2.58) compared to dissimilar PCE (M = 5.69, SD = 2.09) and the condition without any information on PCE (M = 5.63, SD = 2.25). In a Swiss study with law students, similar PCE differed significantly neither from the dissimilar PCE nor from the control condition (no information on PCE), but a similar PCE did increase guilty verdicts about 20% compared to when it was explicitly stated that the defendant had no prior record (Oswald 2009).

Furthermore, studies that did not systematically vary similarity also provide insight into this moderator: Honess and Mathews (2012) found no effect of PCE, although they used similar PCE. However, the case included multiple defendants and only one of them had one prior conviction, which might have weakened the effect of similarity. Likewise, a similar PCE did also not increase guilt ratings compared to both previous acquittal and the explicit statement of not having any prior convictions in Clary and Shaffer (1980). Here, the past charge was a juvenile charge implying that it was long ago and thereby being less informative, supporting Lloyd-Bostock (2000) findings.

Similarity might need to be specified further, because an identical PCE (theft of car radios) increased guilt ratings, but similar PCE (armed robbery as current offense, but minor assault with a knife and shoplifting as PCEs) did not in Schmittat et al. (2022). However, PCE for a home break-in was sufficient in a bank robbery case to increase guilty verdicts (Greene and Dodge 1995). Future research should measure how participants rate the similarity of the two offenses and what participants deduce from similar PCE for their judgments of guilt (e.g., does similarity offer information about habitual cues, motives, criminal propensity; see Howe 1991).

Overall, there is some support for the hypothesis that similarity is a moderator of the PCE effect, but for it to be certainly harmful for the defendant, a similar PCE might need to be qualified further: only when PCE is recent and possibly only when verdicts are made by lay people. Additionally, PCE for sexually assaulting a child biases decision-makers beyond the effect of similarity, but dissimilar PCE (a recent prior conviction is even better than an old dissimilar prior conviction) might even be beneficial for the defendant.

PCE Quantity

Hans and Doob (1976) speculated that their PCE manipulation was too weak for individual decisions (but strong for group decisions), because they only included one PCE and found no effect on individual decisions, whereas Doob and Kirshenbaum (1972) had previously found that seven PCEs (five identical, 2 similar) increased conviction rates. The assumption that more PCE increases the effect of PCE is not supported by Cowley and Colyer (2010): A second PCE did not add more weight than one PCE. Here, one PCE already increased the percentage of guilt verdicts, although the majority of participants in their studies chose “cannot decide” and only about 9–16% chose a guilty verdict at all. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution and more research is needed. Other researchers who used multiple prior convictions found that several prior offenses compared to no prior record led to more severe adjudication and disposition decisions in juvenile defendants (Ruback and Vardaman 1997), or found an effect of PCE in one but not in their other study (Schmittat et al. 2022). At this moment, there is little empirical support for the hypothesis that the number of PCE is associated with an increased likelihood of guilt. However, Schlotthauser and Yundina (2016) analysis of German conviction statistics from 2013 indicates that over 60% of the convicted defendants had prior convictions and half of those defendants had five or more prior convictions (see also Schmittat et al. 2022). Since all the other analyzed studies used only one prior conviction for their PCE manipulation, the experimental studies might therefore represent a very limited view of reality. Future studies should investigate the influence of multiple prior convictions or a more extensive and realistic criminal history.

Admissibility and Limiting Instructions

The introduction of the defendant’s prior record during a trial might be challenged by opposing counsel followed by a ruling on admissibility. If the prior record is inadmissible, judges instruct the jury to not use this piece of evidence to determine guilt of the current offense, but jurors may use it for the evaluation of the defendant’s credibility (USA: Rule 609, Federal Rules of Evidence). A handful of studies investigated whether these judicial instructions can in fact reduce or eliminate the impact of PCE, and results consistently indicate that limiting instructions remain largely ineffective (e.g., Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Greene and Dodge 1995; Honess and Mathews 2012; London and Nunez 2000; Pickel 1995; Wissler and Saks 1985), implying that the basic effect of PCE did not disappear (see also Steblay et al. 2006). Judicial instructions can even backfire and increase guilty verdicts, possibly because jurors have their own opinion about which evidence is fair to use or because limiting instructions put unintended emphasis on the PCE (Pickel 1995). So far, there is little support that the presence of limiting instructions moderates the effect of PCE. Studies about the entrapment defense indicate that PCE only has a negative impact on the verdict when jurors were explicitly allowed to use this information (Borgida and Park 1988; Morier et al. 1996).

Case Characteristics

Ambiguity

A case analysis done by Eisenberg and Hans (2009) indicates that when decision-makers have no other grounds to base their decision on, they start using information about prior convictions. In their case analysis, a prior criminal record only led to more convictions if the overall evidence against the defendant was weak. Thus, the case itself, independent of PCE, needs to be considered when the effects of PCE are evaluated. The question therefore arises whether experimental studies that found a significant effect of PCE were ambiguous cases, which opened the door to extralegal influences (as argued by Clary and Shaffer 1985), and reversely, whether non-significant studies used stronger/weaker cases, where PCE made no or less difference.

Unfortunately, the majority of published articles on this matter do not included detailed materials. The strength of the prosecution’s case or of the arguments of the defense remains vastly unknown. Only a few studies stated that the case material was designed to contain evenly balanced evidence or to be ambiguous cases (e.g., Clary and Shaffer 1980, 1985; Edwards and Bryan 1997; Greene and Dodge 1995; Tanford and Cox 1988; Wissler and Saks 1985), which may have been a reason that the PCE effect even became apparent since PCE offers an additional piece of evidence that may tip the scale towards guilt (Laudan and Allen 2011). Conviction rates and guilt ratings in control conditions mostly support the classification (Clary and Shaffer 1980: 4.77 on a scale from 1 = very unlikely guilty to 9 = very guilty; Clary and Shaffer 1985: 20% after deliberation; Edwards and Bryan 1997: about 2.5 on a guilt index from − 9 = not at all guilty to + 9 = extremely guilty; Wissler and Saks 1985: 35% in the auto-theft case, 50% in the murder case; Tanford and Cox 1988: baseline of 48% liability verdict) with the exception of Greene and Dodge’s study which only led to 17% conviction rate (1995) and therefore could be classified as weak. However, half of these studies with ambiguous cases found no main effect of PCE (Clary and Shaffer 1980, 1985; Edwards and Bryan 1997; Oswald 2009) and London and Nunez (2000) found an effect of PCE in pre-deliberation conditions, although the case was designed to be weak (conviction rate of 26%), contradicting the explanation that PCE only has an effect in close cases (Laudan and Allen 2011).

The conviction rates of the other cases used in PCE research vary greatly, starting at no convictions at all (after deliberation, Hans and Doob 1976), or only 8–10% convictions (Cowley and Colyer 2010; Oswald 2009), and going up to 35–50% (Pickel 1995; Schmittat et al. 2022). The results of these studies regarding a main effect of PCE vary just as much.

Although ambiguous cases might elicit feelings of uncertainty, which in turn makes people vulnerable to heuristics (Tversky and Kahneman 1974), the available studies do not support case strength as moderator for PCE. However, future studies should vary case strength systematically in order to disentangle this factor. Furthermore, it should be investigated, if the PCE assists in the interpretation of ambiguous evidence. If PCE is irrelevant or not connected to any other evidence, case strength might not be an important moderator. On the other hand, if PCE offers a crucial cue and dissolves ambiguity, PCE might tip the scale towards conviction (see below for a continuation of this argument).

Seriousness of Current Offense

Lloyd-Bostock (2000) investigated three different charges – handling of stolen goods, indecent assault on a woman, or deliberate stabbing – but results indicated that the specific case was irrelevant for the investigated PCE factors. The irrelevance of seriousness is also supported by Wissler and Saks (1985), who used a minor (auto-theft) and a major offense (murder) for their study (see also Cornish and Sealy 1973), but found no effect of case. Only in one study about juvenile defendants PCE interacted with seriousness of the crime with regard to the verdict: in theft and battery cases, long prior records led to more severe adjudications than no prior record, but this interaction did not become apparent in drug crimes (Ruback and Vardaman 1997).

Overall, seriousness of the current offense does not seem to be a relevant factor for the effect of PCE. Only under certain conditions (e.g., juvenile theft and battery cases), seriousness might become more significant.

Methodological Moderators

Many of the above-mentioned factors have been studied systematically, but methodological moderators have been generally overlooked. Diverse methodological approaches could possibly account for differences of results and should therefore be examined in future studies, both theoretically and experimentally. For example, the operationalization of a control condition is inconsistent, PCE is introduced to the participants in multiple ways, and stimulus materials vary greatly from short vignettes to extensive video materials engaging the participants to different degrees.

Salience

Devine and Caughlin (2014) observed that PCE is sometimes made very salient or only conveyed in passing without calling much attention to it. The latter might explain the modest effect of PCE and why the existing empirical literature might not fully capture the impact of a prior conviction. An examination of the stimulus materials supports their observation: Some studies make PCE very salient, for instance by using a voice-over commentary describing the previous conviction (Lloyd-Bostock 2000, 2006). Also, all studies that varied admissibility or included judicial instructions on how to use PCE automatically put more emphasis on PCE (e.g., Allison and Brimacombe 2010; Borgida and Park 1988; Clary and Shaffer 1980, 1985; Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Edwards and Bryan 1997; Greene and Dodge 1995; Hans and Doob 1976; Honess and Mathews 2012; Morier et al. 1996; Pickel 1995) compared to studies that simply mention PCE within an array of other case facts (e.g., Cowley and Colyer 2010; Schmittat et al. 2022; Wissler and Saks 1985). However, salience of PCE does not seem to contribute to the explanation of the divergent results. For instance, Hans and Doob (1976) found that PCE had no effect on individual jurors, even though PCE is highlighted by the limiting instructions. Furthermore, Schmittat et al. (2022, study 1) found a main effect of PCE, although PCE was not emphasized at all.

Making PCE more salient does not automatically trigger a negative reaction from participants towards the defendant, as shown by Honess and Mathews (2012). In their first study, PCE was mentioned twice in the stimulus materials and PCE had no effect on guilt judgments. In the subsequent interviews about participants’ judgments, there was little reference to PCE. Therefore, in their second study, the case materials mentioned PCE three times, but again, there was no association between PCE and guilt. However, 24 participants out of 60 referred to PCE but only 12 of them made negative character comments. Ten participants were sympathetic to the defendant and mentioned the unfair use of PCE. Therefore, participants’ reaction to PCE might be more complex than originally assumed and probably depends on other variables.

It could therefore be speculated that the emotional response to PCE is more important than salience of PCE, which is supported by a study by Edwards and Bryan (1997): their description of PCE either contained an emotionally upsetting account of a violent crime or the prior conviction was stated factual and legalistic (pretested). The affective PCE but not the factual PCE increased guilt and sentencing ratings compared to a control condition (no information about PCE) if it was also inadmissible. This indicates that the PCE effect does not depend on perception (salience) alone, but could also depend on the emotional reaction PCE provokes. Overall, studies should check if participants processed PCE and how they evaluate it or react to it (yet manipulation checks are rarely conducted, see next paragraph).

Control Condition and Manipulation Checks

The definition of a control condition is not identical across studies: Most control conditions simply do not mention any prior criminal history of the defendant at all (e.g., Cowley and Colyer 2010; Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Edwards and Bryan 1997; Hans and Doob 1976; London and Nunez 2000; Schmittat et al. 2022). Other studies explicitly state that the defendant has no prior conviction (e.g., Borgida and Park 1988; Clary and Shaffer 1980, 1985; Greene and Dodge 1995). Only Lloyd-Bostock (2000, 2006) and Oswald (2009) included both control conditions. In Oswald (2009), the two control conditions did not differ, but the largest differences in guilty verdicts and guilt probability were found between similar PCE and no prior conviction, but significance tests could not be conducted or were not significant because the study was underpowered. In Lloyd-Bostock (2000), guilty verdicts of both control conditions were significantly lower than the verdict of recent PCE before deliberation. But after deliberation, a recent similar PCE was only significantly different to the control condition in which PCE was explicitly absent (mentioned by the defense as proof of a good character), but not to the condition where PCE was simply not commented on. More importantly, the study provides insights into participants’ beliefs about the defendant: when PCE was simply not mentioned, about 60% of the participants (general public) automatically assumed that the defendant had at least one prior conviction (Lloyd-Bostock 2000; 50% of lay magistrates, Lloyd-Bostock 2006), because otherwise the defense attorney would have explicitly stated the lack of a prior record to support the defendant’s good character. Thus, when participants receive no information about any prior convictions, researchers should assess if participants have any assumptions about the defendant’s criminal history. This could potentially explain null effects when participants in both conditions (no PCE mentioned and PCE) base their judgments on essentially the same premises (e.g., defendant is a criminal).

Furthermore, the majority of the studies did not include a manipulation check of PCE (e.g., Allison and Brimacombe 2010; Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Hans and Doob 1976; Lloyd-Bostock 2000; Pickel 1995); therefore, it remains uncertain whether participants paid attention to the prior record, processed it, or remembered the prior record correctly. Clary and Shaffer’s studies (1980, 1985) did include a manipulation check and the authors point out that the prior record manipulation was in fact noted according to the condition and no participants were excluded. However, the authors only checked if participants were more certain that the defendant had a prior record compared to no prior record on a 9-point scale (1 = previously convicted, 5 = uncertain, 9 = not previously convicted), but did not assess if participants recognized the similarity between PCE and current charge, which they had manipulated. The only other study that included a manipulation check was by Oswald (2009). She excluded participants if they failed the manipulation check. Her study did not find any PCE effect on judgments of guilt.

Sample

As it is often the case with experimental studies before the replication crisis in social psychology (e.g., Nelson et al. 2018), many studies are greatly underpowered to detect a small effect of PCE. A one factorial design would require about 213 participants per cell to detect a modest PCE effect (d = 0.24, α = 5%, power = 80%; Devine and Caughlin 2014), but most studies used 10 to 30 participants per cell (see Table 1). Those studies should therefore be interpreted with caution and more experimental studies are essential to draw any valid assumptions about any positive or negative effects of the defendant’s criminal history.

Additionally, studies vary with respect to the chosen sample: some recruited potential jurors (i.e., general public, Cowley and Colyer 2010; Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Honess and Mathews 2012; Lloyd-Bostock 2000), others recruited psychology students (e.g., Borgida and Park 1988; Pickel 1995), one study recruited legal professionals (Ruback and Vardaman 1997), four studies had law students as a substitute for legal experts (Oswald 2009; Schmittat et al. 2022), and one study recruited lay magistrates (Lloyd-Bostock 2006). So far, the available results do not reveal a pattern that PCE effects might depend on the chosen population.

Individual vs. Group Decisions

Most studies focused on individual decisions and only a few focused on the effect of deliberation. There is some evidence that the deliberation process could de-bias juror’s individual evaluation of PCE. For instance, Hans and Doob (1976) concluded that PCE had no effect on individual decisions, but PCE increased conviction rates in groups of four after deliberation. However, the exact percentages reveal a different picture: Without PCE, conviction rates after individual decisions are higher than after deliberation (individual: 40%; group: 0%), but conviction rates are roughly the same when PCE was present (individual: 45%; group: 40%). Thus, the absence of PCE led to a different evaluation of the case, but not the information that the defendant has prior conviction. Deliberation transcripts indicated that juries do discuss prior convictions, but participants’ subjective influence of PCE was small to not existent. Interestingly, distortions (errors in recalling case facts) were corrected more often in groups with PCE, possibly, because these groups were alerted to potential negative biases (Hans and Doob 1976).

In London and Nunez (2000), deliberation in groups of eight to twelve people lessened the effect of inadmissible PCE, which is also supported by Lloyd-Bostock’s study (2000). Here, the act of discussing the case with others reduced all guilt ratings on a descriptive level and accentuated the difference between recent dissimilar (lowest rating) and all other variations (except old dissimilar PCE, which was also a low rating of guilt). The difference between recent similar (highest guilt rating) and the two control conditions (no prior convictions and no information about any PCE) disappeared after deliberation; hence, the basic effect of PCE was gone. Thus, jurors can correct others’ biases and facilitate different perspectives (e.g., Honess and Mathews 2012). Only one study indicates that deliberation could amplify the effect of PCE; however, this was only in the combination with pleading the 5th amendment (Clary and Shaffer 1985).

Therefore, there is some support for the hypothesis that deliberation can reduce harmful effects of PCE. Overall, research on the effect of limiting instructions indicates that jury deliberation might diminish the influence of damaging inadmissible information (Steblay et al. 2006).

Richness of Stimulus Materials

Honess and Mathews (2012) suggested that PCE effects might depend on the richness of stimulus materials. They argue that PCE was mostly found in studies that used short written stimuli (e.g., Greene and Dodge 1995; Hans and Doob 1976; Wissler and Saks 1985). In contrast, Honess and Mathews (2012) used a video of a re-enactment of a real case that lasted for almost 2 h (including opening and closing statements and the judge’s post-trial instructions). They did not find any support for the hypothesis that PCE leads to high confidence of guilt (Honess and Mathews 2012). Innately, audiotapes and videos contain more contextual information and can lead to different judgments than the same information in a written format (e.g., Sleed et al. 2002). It is thus difficult to compare a study that uses an audiotape of 25 min (Pickel 1995) with a study that uses short vignettes (e.g., Schmittat et al. 2022; Wissler and Saks 1985). However, the overall richness of stimulus materials, independent of modality, does not seem to explain divergent effects of PCE. For instance, the videos Lloyd-Bostock (2000, 2006) used were about half an hour long and partly based on real trials. Here, PCE increased guilty evaluations under certain conditions (when recent and similar) compared to other conditions (dissimilar, old), especially before deliberation. In contrast, PCE only increased convictions in the 2-h video used by Borgida and Park (1988) when the judicial instructions specifically allowed participants to use PCE (for the evaluation of an entrapment defense). Stimulus richness surely is an important factor concerning external validity of stimulus materials, yet it does not seem to be a moderator for PCE.

Recommendations for Future Research

The meta-analysis by Devine and Caughlin (2014) concluded that PCE only has a modest effect on judgments of guilt and that this effect likely depends on moderators, but which could not be studied systematically due to a lack of available experimental studies. The present literature review continues this line of research by reviewing the already mentioned moderators (salience and similarity; Devine and Caughlin 2014) but also by identifying further potential moderators regarding PCE characteristics, case characteristics, and methodological moderators in the attempt to disentangle the prevailing inconsistent PCE results on the one hand and to re-ignite research interest in a topic that clearly presents an abundance of unanswered questions on the other hand. Overall, the discussed studies indicate that PCE can increase guilty verdicts, but only under very specific conditions.

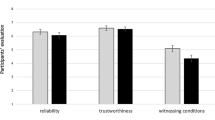

The majority of the available studies hypothesized that perceived criminal propensity (or an overall negative impression of the defendant due to the PCE) explains higher conviction rates in PCE conditions. This is partially supported by reduced credibility ratings and higher perceived dangerousness of the previously convicted defendant (Allison and Brimacombe 2010; Cowley and Colyer 2010; Doob and Kirshenbaum 1972; Greene and Dodge 1995; Wissler and Saks 1985). However, not just any PCE automatically leads to a negative character evaluation (Honess and Mathews 2012). Dispositional cues may only derive from similar but not dissimilar PCE (Wissler and Saks 1985). Since multiple studies which presented similar PCE did not find any effect (Clary and Shaffer 1980; Lloyd-Bostock 2000; Schmittat et al. 2022), the subjective understanding of “similarity” needs to be explored, as well as what jurors deduce from a similar compared to a dissimilar PCE. Lloyd-Bostock’s studies demonstrated the importance of asking decision-makers about their inferences (2000, 2006). Other underlying mechanisms have not received as much attention but should be explored further. For instance, PCE could lower the standard of proof; thus, the threshold of convicting a defendant with a prior record might be lower, since the defendant is perceived to not be a completely innocent person anymore (Laudan and Allen 2011). However, this remains a theoretical approach which has not been tested experimentally.

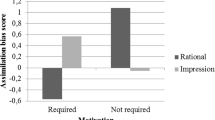

Overall, studying one specific moderator that is connected to a certain underlying cognitive mechanism probably implies the experimental investigation of a potentially narrow concept. Thus, the legal implications for both legislative authorities and the development of trial strategies would be very limited, which would in turn make the research endeavor of this extralegal variable almost trivial. Therefore, a different research approach seems to be necessary. Therefore, instead of focusing on single moderators and one specific underlying mechanism, PCE should to be studied within legal decision-making models. Research could therefore focus more on answering the following questions: how much weight does PCE have within the presented case and does the knowledge of PCE change the perception and interpretation of the other evidence? Does PCE provide information that is clearly needed? Is PCE important for the story? According to the story model (e.g., Pennington and Hastie 1986), decision-makers automatically construct stories out of the presented trial evidence. More specifically, jurors reproduce evidence in causal event chains and episode structures instead of simply stating a list of evidences. Their own interpretations of the evidence, inferences, or generic expectations about human behavior are integrated into a story. Also, if evidence is not directly related to their story, it is systematically deleted (Pennington and Hastie 1986). Legal story-telling is commonly used and accepted as a persuasion tool in court (e.g., Mazzocco and Green 2011). The question therefore is as follows: under which circumstances does PCE contribute to the story?

Since legal decision-making involves complex information processing and PCE is only one of many pieces of evidence, it is difficult to evaluate the effect of PCE without considering the impact other evidence has on the evaluation of PCE and vice versa. For example, PCE can evoke stereotypes (e.g., Feather and Souter 2002; Greene and Dodge 1995; Lloyd-Bostock 2000; Otto et al. 1994) and this may affect how other evidence is perceived, interpreted (shifting ambiguous to weak/strong evidence), or recalled (e.g., Hans and Doob 1975). PCE could facilitate coherence shifting, which is a bidirectional confirmation bias (Simon 2004). Hence, PCE can change how subsequent evidence is evaluated, but it can also lead to a re-evaluation of evidence that was presented beforehand. Additionally, emerging conclusions (inclinations towards one verdict) can influence the evaluation and integration of evidence as well (e.g., Otto et al. 1994). The mental representation that the juror has formed of the case is therefore continuously adapting, ultimately leading to a coherent final decision. Thus, the effect of PCE can and should not be evaluated without considering how PCE changes the reasoning about other evidence (Cowley and Colyer 2010; Honess and Mathews 2012). The influence of PCE might vastly depend on the case and other available evidence, as discussed above.

For instance, if the case consists mainly out of circumstantial evidence, PCE – especially similar PCE – could provide the important clue that changes the interpretation of the whole case. For example, a defendant is accused of breaking into multiple cars and stealing the cars’ radios. The police encountered the defendant in the parking garage, but the defendant’s car was also broken into and somebody tried to hot wire it. The defendant only became a suspect, because four radios were found hidden underneath the hood of the defendant’s car, which could be perceived as very odd. The information that the defendant has multiple convictions for stealing car radios might provide the necessary information to understand this (he is experienced, hid the stolen radios, staged his car; Schmittat et al. 2022). It could be speculated if other types of prior convictions would also change the interpretation of the otherwise ambiguous evidence to this degree – in this study, PCE increased guilt judgments.

Research by Cowley and Colyer (2010) supports the hypothesis that PCE changes the evaluation of other evidence, which is weak by itself, and that this goes beyond a simple additive effect. Participants were presented with a child protection case, similar PCE, and information about handedness (deadly blow was delivered either by a right-handed or by a left-handed individual and the defendant was either left- or right-handed). Only in combination of PCE and left-handedness (less prevalent within the population), participants chose “guilty” more often than “cannot decide” or “not guilty”. Additionally, in this condition, participants created fewer alternative explanations when asked to state reasons for their choice – they already had formed a conclusive story (e.g., Pennington and Hastie 1986). The same was not true for right-handedness, possibly because it provides very little probative value, which cannot be elevated through PCE (Cowley and Colyer 2010).

Conclusions

So far, there is no empirical consensus whether the information about a defendant’s legal history is harmful to the defendant or rather irrelevant. The present literature review, although limited to published studies in English, discussed a number of moderators that could serve to disentangle the conflicting results. PCE characteristics, case characteristics, and methodological moderators were discussed. Overall, not just any PCE can be harmful to the defendant, but under certain conditions, PCE does increase the probability of a guilty verdict. Future studies should focus less on direct effects of PCE and its moderators and more on indirect effects of PCE (e.g., general fit of PCE into the case, impact on other evidence). Lastly, stimulus materials should be extensively pretested (e.g., on ambiguity, PCE perception, emotional reaction to case and to PCE) and a detailed description of all materials should be included into supplementary materials by default to make the overall context of PCE more accessible to other researchers.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Notes

In certain cases, PCE is allowed beyond sentencing, e.g., if the prior conviction offers central information about the defendant’s criminal modus operandi or if it indicates a commercially intended crime.

Not enough details were available on this study to include it in the analysis.

References

Allison M, Brimacombe C, a E. (2010) Alibi believability: the effect of prior convictions and judicial instructions. J Appl Soc Psychol 40(5):1054–1084. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00610.x

Borgida E, Park R (1988) The entrapment defense - juror comprehension and decision making. Law Hum Behav 12(1):19–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01064272

Clary EG, Shaffer DR (1980) Effects of evidence withholding and a defendant’s prior record on juridic decisions. J Soc Psychol 112:237–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1980.9924325

Clary EG, Shaffer DR (1985) Another look at the impact of juror sentiments towards defendants on juridic decisions. J Soc Psychol 125(5):637–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1985.9712038

Cornish WR, Sealy AE (1973) Juries and the rules of evidence. Crim Law Q 16:208–223

Cowley M, Colyer JB (2010) Asymmetries in prior conviction reasoning: truth suppression effects in child protection contexts. Psychol Crime Law 16(3):211–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802612916

Criminal Justice Act of England and Wales, Sections 98 to 113 (2003) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/44/contents

Devine DJ, Caughlin DE (2014) Do they matter? A meta-analytic investigation of individual characteristics and guilt judgments. Psychol Public Policy Law 20(2):109–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000006

Doob AN, Kirshenbaum HM (1972) Some empirical evidence of the effect of s.12 of the Canada Evidence Act upon an accused. Crim Law Q 15:90–91

Edwards K, Bryan TS (1997) Judgmental biases produced by instructions to disregard: the (paradoxical) case of emotional information. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 23(8):849–864. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297238006

Eisenberg T, Hans VP (2009) Taking a stand on the stand: the effect of a prior criminal record on the decision to testify and on trial outcomes. Cornell Law Rev 94:1353–1390

Feather NT, Souter J (2002) Reactions to mandatory sentences in relation to the ethnic identity and criminal history of the offender. Law Hum Behav 2(4):417–438. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016331221797

Greene E, Dodge M (1995) The influence of prior record evidence on juror decision making. Law Hum Behav 19(1):67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01499073

Hans VP, Doob AN (1976) Section 12 of the Canada Evidence Act and the deliberations of simulated juries. Crim Law Q 18(2):235–253

Honess TM, Mathews G, a. (2012) Admitting evidence of a defendant’s previous conviction (PCE) and its impact on juror deliberation in relation to both juror-processing style and juror concerns over the fairness of introducing PCE. Leg Criminol Psychol 17(2):360–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8333.2011.02019.x

Howe ES (1991) Judged likelihood of different second crimes: a function of judged similarity. J Appl Soc Psychol 21(9):697–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1991.tb00543.x

Jones S, Harrison M (2009) To testify or not to testify — that is the question: comparing the advantages and disadvantages of testifying across situations. Appl Psychol Crim Justice 5(2):165–181

Laudan L, Allen RJ (2011) The devastating impact of prior crimes evidence and other myths of the criminal justice process. J Crim Law Criminol 101(2):493–527. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1670999

Lloyd-Bostock S (2000) The effects on juries of hearing about the defendant’s previous criminal record: a simulation study. Crim Law Rev 56:734–755

Lloyd-Bostock S (2006) The effects of lay magistrates of hearing that the defendant is of “good character”, being left to speculate, or hearing that he as a previous conviction. Crim Law Rev 189–212

London K, Nunez N (2000) The effect of jury deliberations on jurors’ propensity to disregard inadmissible evidence. J Appl Psychol 85(6):932–939. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.85.6.932

Mazzocco PJ, Green MC (2011) Narrative persuasion in legal settings: what’s the story? The Jury Expert 23(3):27–38

Morier D, Borgida E, Park RC (1996) Improving juror comprehension of judicial instructions on the entrapment defense. J Appl Soc Psychol 26(20):1838–1866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb00102.x

Nelson LD, Simmons J, Simonsohn U (2018) Psychology’s renaissance. Annu Rev Psychol 69(1):511–534. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011836

Oswald ME (2009) How knowledge about the defendant’s previous convictions influences judgments of guilt. In: Oswald ME, Bieneck S, Hupfeld-Heinemann J (eds) Social Psychology of Punishment of Crime. John Wiley & Sons, pp 357–377

Otto AL, Penrod SD, Dexter HR (1994) The biasing impact of pretrial publicity on juror judgments. Law Hum Behav 18(4):453–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01499050

Pennington N, Hastie R (1986) Evidence evaluation in complex decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol 51(2):242–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.2.242

Pickel KL (1995) Inducing jurors to disregard inadmissible evidence: a legal explanation does not help. Law Hum Behav 19(4):407–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01499140

Ruback RB, Vardaman PJ (1997) Decision making in delinquency cases: the role of race and juveniles’ admission/denial of the crime. Law Hum Behav 21(1):47–67. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024866026608

Sealy P, Cornish W (1973) Juries and the rules of evidence. Crim Law Rev B 208–223

Shaffer DR, Case T (1982) On the decision to testify in one’s own behalf: effects of withheld evidence, defendant’s sexual preferences, and juror dogmatism on juridic decisions. J Pers Soc Psychol 42(2):335–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.2.335

Simon D (2004) A third view of the black box: cognitive coherence in legal decision making cognitive coherence in legal decision making. Univ Chicago Law Rev 71(2):511–586

Schlotthauser S, Yundina E (2016) Schuld und Vorurteil: Zum Einfluss von Vorstrafen auf das Schuldurteil. Recht Und Psychiatrie 34:43–49

Schmittat SM, Englich B, Sautner L, Velten P (2022) Alternative stories and the decision to prosecute: an applied approach against confirmation bias in criminal prosecution. Psychol Crime Law 28(6):608–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1941013

Sleed M, Durrheim K, Kriel A, Solomon V, Baxter V (2002) The effectiveness of the vignette methodology: a comparison of written and video vignettes in eliciting responses about date rape. S Afr J Psychol 32(3):21–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630203200304

Steblay NK, Hosch HM, Culhane SE, McWethy A (2006) The impact on juror verdicts of judicial instruction to disregard inadmissible evidence: a meta-analysis. Law Hum Behav 30(4):469–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9039-7

Tanford S, Cox M (1988) The effects of impeachment evidence and limiting instructions on individual and group decision making. Law Hum Behav 12(4):477–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01044629

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185(4157):1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Wissler RL, Saks MJ (1985) On the inefficacy of limiting instructions: when jurors use prior conviction evidence to decide on guilt. Law Hum Behav 9(1):37–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01044288

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nicole Niewiak and Nicolas Alef for assisting with the literature search.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Johannes Kepler University Linz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author. Informed consent was not necessary to be obtained.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmittat, S.M. Prior Conviction Evidence: Harmful or Irrelevant? A Literature Review. J Police Crim Psych 38, 20–37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-022-09557-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-022-09557-z