Abstract

Police officers are frequently confronted with various stressors that may affect their mental health. Psychological resilience may protect against these effects. For this purpose, a Mental Strength Training (MST) was developed by the Dutch Police Academy aimed at psychological resilience enhancement. The present three-wave study examined efficacy of this training using a quasi-experimental study design among police officers (N Total = 305, n Experimenal = 138, n Comparison = 167). Additionally, we compared between officers in the experimental and comparison group recently confronted with a potentially traumatic event (N Total = 170, n Experimenal = 74, n Comparison = 96). Questionnaires on resilience (Mental Toughness Questionnaire-48 (MTQ-48) and Resilience Scale-nl (RS-nl)), mental health disturbances (Symptoms CheckList 90-R (SCL-90-R) and Self-Rating Inventory for PTSD (SRIP)), were administered pre-training, and about 3 and 9 months post-training. Mixed-effects models showed training effects on Interpersonal Confidence. Similar analyses among officers with recent potentially traumatic event experience showed significant training effects for the RS-nl subscale of Acceptance of Self and Life, MTQ-48 total score, and the MTQ-48 subscale of Interpersonal Confidence. However, all effects yielded small effect sizes according to Cohen’s d, and are therefore of limited practical relevance. Officer’s appraisal of training benefits on resilience enhancement was largely negative. We found no indications that 4-day training substantially improved officer’s psychological resilience or mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Policing is often considered a stressful and demanding job. While police officers are confronted with numerous potentially traumatic events (PTEs), they are expected to maintain adequate functioning at all time. The types of stressors with which they are confronted are not only police-typical operational stressors, but also include organizational stressors such as managerial strains. Furthermore, as for anybody from the general population, stressors are a natural occurrence in the police officer’s personal life (Berg et al. 2006; Brough 2004; Cheong and Yun 2011; Collins and Gibbs 2003; Maguen et al. 2009; Mumford et al. 2015; van der Velden et al. 2010; Pavšič Mrevlje 2014; van der Velden et al. 2013; Violanti and Aron 1993).

These stressors are associated with the development of mental health disturbances (MHDs), such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, burnout, and sleep problems among police officers (Berg et al. 2006; Brough 2004; Charles et al. 2011; LeBlanc et al. 2008; Maguen et al. 2009; Mumford et al. 2015; van der Velden et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2010).

Literature on dealing with stress provides numerous factors to distinguish between person that may or may not be able to cope with stressful circumstances (DiGangi et al. 2013). Among the factors that can be either demographic, social, or trait-like, psychological resilience is a factor often mentioned in relation to dealing with stressful circumstances (de Terte et al. 2014). It has numerous definitions (McGeary 2011), but can be understood as a personal characteristic as being able to perform under stress and not affected by its potentially harmful consequences. Furthermore, psychological resilience is thought to be a malleable characteristic of individuals, and therefore the concept is central to stress management interventions (Papazoglou and Andersen 2014). The need for stress management among law enforcement is, among other reasons, important because the police force is one of the public organizations which actively exerts the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force. This particular characteristic puts a great deal of responsibility on the police force towards the general public. Not being able to properly deal with stress while exerting this monopoly can have detrimental effects. For example, Cheong and Yun (2011) show that perceived operational stress is positively related to use of force frequency among police officers. Another study by Kop et al. (1999) found that officers with higher levels of burnout had a more positive attitude towards the use of force in the line of duty. Lastly, the study of Barton et al. (2004) showed that officers with low hardiness scores, a concept closely related to psychological resilience, made more incorrect decisions in threatening situations than officers with high hardiness scores.

A report on the functioning of Dutch police officers in 2011 concluded that the Dutch police officers were (strongly) limited in their employability as officers: the required psychological resilience was at risk (Andersson Elffers Felix 2011). Furthermore, the report concluded that approximately 25% of all police officers suffered from MHDs, ranging from PTSD to anxiety. Because of these alarming numbers, the School for Hazard & Crisis Management of the Dutch Police Academy developed a new training, the so-called Mental Strength Training (MST), aimed at enhancing psychological resilience of officers (Politieacademie 2012a).

Mental Strength Training

It is common within law enforcement to offer resilience enhancement training, or similar concepts such as stress management interventions, that should help officers to perform their role and reduce potential negative consequences (Miller 2008; Papazoglou and Andersen 2014). To date, several intervention programs had been developed such as mental imaging training (Arnetz et al. 2009), resilience training (Devilly and Varker 2013), and Heartmath® stress techniques (McCraty et al. 2009).

These programs, and the training in the current study, have in common that they teach skills to police officers that could be applied while preparing for a confrontation with a stressful event, while experiencing stressful events, or in the aftermath of a stressful event. The training in the current study, the Mental Strength Training, used three domains in which specific skills are taught: challenge, control, and confidence (Politieacademie 2012a). These concepts are similar to the four subcomponents of the concept of mental toughness, excluding the fourth mental toughness domain of commitment. Mental toughness is a concept rooted in sports psychology and is a characteristic of individuals who are able to perform well under stressful conditions (Clough et al. 2002). It is a concept very similar to psychological resilience. In fact, the concept of mental toughness stems from Kobasa’s hardiness concept (Kobasa et al. 1982); one of the most used conceptualizations of psychological resilience. The skills taught in the course are aimed at enhancing one of the three domains of psychological resilience.

In the challenge domain, officers were taught the skill of goal setting, which should enhance confidence and motivation, and enhance attention to the important aspects of handling the upcoming task. Visualization was also a part of the challenge domain, and taught officers to visualize a real-life event, which could be used as a learning experience for preparing to handle stressful situations (Politieacademie 2012a).

Energy management, in the format of the previously developed Heartmath® and vitality management, was the first skills taught in the control domain. Central to energy management is to control physical, emotional, and mental reactions that arise from stressful events. Recognizing these stress reactions by the officer might dampen the negative effects arising from them. The control domain also contains attention control, teaching officers to focus and keep focus on the specific task at hand (Politieacademie 2012a).

In the last domain, confidence, action-reflection is the first component. It focuses on self-evaluating one’s action to learn from them, supposedly leading to more confidence in future situations. Lastly, recognizing negative thoughts and emotions and the ability to bend these towards more positive appraisals of stressful event experiences is a skill taught within the confidence domain. The negative thoughts and emotions are considered to negatively affect experienced stress, leading to other negative consequences (Politieacademie 2012a).

The domains and all the individual components were derived from interventions and psychological insights created using sports populations, that is: athletes and management of athletes. It is expected that these interventions, and the logic of its resilience enhancement capabilities, are also applicable to other populations, including the policing population, as they both are often expected to perform under heightened pressure and in changing difficult circumstances (Politieacademie 2012c). Moreover, most parts of the current training were used in previous studies on police stress training. The different components in the current study were also used in training developments of previous studies. However, in those instances, components of the current training were used, while mixing in other components not used in the current training. Within these different compositions of training components, a plurality of outcomes had been associated with these differing training types. Among others, these training types have been found to enhance general health (Arnetz et al. 2013; Backman et al. 1997), mental health (Williams et al. 2010), and/or reduce stress levels (Arnetz et al. 2009; McCraty et al. 1999, 2009; Ranta and Sud 2008; Zach et al. 2007).

However, whether these interventions are capable of either enhancing psychological resilience or reducing mental health symptoms within the law enforcement is not well established. Several studies on the effects of training programs among officers as described earlier (e.g., Arnetz et al. 2009) showed promising results. However, a systematic review by Peñalba et al. (2008) report psychological and psychosocial benefits found within small-scale studies, but stress the need for more well-designed studies to establish more thorough proof of efficacy of these programs. Moreover, the systematic review on police stress management interventions by Patterson et al. (2012) refrains from drawing conclusions “given the weakness of the research designs” (Patterson et al. 2012, p. 25). Both these reviews which specifically focus on police training (Patterson et al. 2012; Peñalba et al. 2008) stress the need for more rigorous designs, applying, among others, larger sample sizes. Another systematic review on resilience enhancement training for the police and other occupations, such as teachers, managers, and soldiers, by Robertson et al. (2015), showed ambiguous results; both effects and non-effects within and between studies were found on a variety of outcome measures, such as psychological resilience and mental health. Taken together, these reviews show that proof of resilience enhancement training for law enforcement is ambiguous in its outcomes and previously applied study designs are lacking robustness.

Present Study

The present study examined the effects of the MST training aimed at psychological resilience enhancement of Dutch police officers. It did so while considering some of the most important issues of reviewers of police stress interventions (Peñalba et al. 2008; Patterson et al. 2012). First of all, the applied sample size was larger as compared to previous research. Furthermore, the applied quasi-experimental study design was in accordance with suggestions made by Patterson et al. (2012) as the best fitting design for analyzing stress management interventions.

The research question of the present three-wave quasi-experimental study was to what extent psychological resilience and mental health improved after the training compared to non-trained officers. First, we assessed the efficacy of the program among all participating police officers, additionally we examined potential benefits among police officers who were recently exposed to PTE. Considering promising past results (e.g., Arnetz et al. 2009), we hypothesized that the MST would enhance psychological resilience in an experimental group as compared to a comparison group. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the trained group showed less post-training MDH as compared to a comparison group.

Methods

Training Delivery

Within three consecutive 8-h training days, the content was presented in lectures and practical exercises. An additional brush-up day should anchor the skills learned and is used to reflect on the experience of applying the learned skills thus far. Teaching in the training was done by two trainers, who had often previously worked as a police officer themselves, although non-police personnel was also allowed to become a trainer. Specific parts within the energy management component were given by external, certified trainers in the field of sports psychology, namely vitality management and Heartmath® stress techniques. Training was provided to groups no larger than 16 persons. All police officers are eligible to be invited to participate in the MS training, but a primary focus is on executive functions rather than managerial functions (Politieacademie 2012a, b, c).

Respondents and Procedures

A quasi-experimental design was used to examine the effectiveness of the MST, with a pre-training assessment (T0) and two follow-up measurements at about 3 (T1) and 9 (T2) months after T0. Questionnaires contained the similar content across all measurement moments, with the exception of questions on experiences and usefulness of MST at T1 and T2 among trained officers. According to governmental policy (Politieacademie 2012c), all officers should participate in the MST. In principle, there were no exclusion criteria for participating in the MST. However, based on judgments by officer’s team leaders, officers could be excluded from participation in the training due to severe mental health issues, although they are not explicitly not allowed to participate. The experimental group (n = 138), consisting of training enrolled teams, was asked to fill paper questionnaires prior to the training at the training location. Off the participating police officers, two persons indicated they were enrolled on their own request, while the remainder was referred by management policy which demanded every officer to be trained (Politieacademie 2012c).

The comparison group (n = 167) was formed by randomly selecting and contacting potential respondents within four different regions in The Netherlands, who had not yet participated in the MST and were not scheduled to do so within the time period of the current study. Enrollment in the study and baseline measurements took place between May and August of 2013. Additional recruitment for the comparison group occurred in September and October of 2013. The comparison group was asked to fill out postal questionnaires during the same period and similar time intervals as the experimental group. To minimize attrition, reminders were sent out to non-respondents. This resulted in variation in length between baseline and the follow-up measurement of approximately 2 months.

All respondents gave their written informed consent. The current study was approved by the Psychological Ethical Testing Committee (PETC) of Tilburg University.

Measurement Instruments

Psychological Resilience

There is a wide variety of measurements of psychological resilience available tapping into psychological resilience with distinct nuances (Windle et al. 2011). Since the MST is strongly rooted in sports psychology, and because mental toughness is a core concept used in developing the MST, the Mental Toughness Questionnaire-48 (MTQ-48) (Clough et al. 2002) measure of psychological resilience was used. Items of this questionnaire are formulated in such a manner that they are applicable to adult populations. However, to the knowledge of the authors, it has never been used to measure psychological resilience among police officers. Therefore, the Resilience Scale-nl (RS-nl), a measure of psychological resilience commonly applied to general adult populations, was added.

The 48 items of the MTQ-48 are scored on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more mental toughness (Clough et al. 2002). Cronbach’s alphas for the entire sample’s baseline measurement (N = 1094) Total score, Challenge (8 items), Commitment (11 items), and Interpersonal Confidence (7 items) were .91, .72, .76, and .71, respectively. Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales Confidence in Abilities, Emotional Control, and Life Control were all below .70, and were therefore excluded from further analysis.

The RS-nl is a widely used and established resilience measure in adult populations (Portzky 2008; Portzky et al. 2009). The 25-item RS-nl provides, in addition to its total score, three scores on subscales: Acceptance of Self and Life (7 items), Personal Competence (12 items), and Dealing with Difficult Circumstances (5 items). For analytic purposes, we chose to use the five-point Likert scale as developed originally by Wagnild and Young (1993), instead of four-point Likert scales. Cronbach’s alphas of the entire sample’s baseline measurement (N = 1094) were .93, .79, .87, and .79 for the scale Total score, Acceptance, Personal Competence, and Dealing with Difficult Circumstances, respectively.

Mental Health Disturbances

Depression (16 items), anxiety (10 items), and hostility symptoms (6 items) were assessed using the Symptoms CheckList 90-R (SCL-90-R), with five-point Likert scales (Arrindell and Ettema 1986; Buwalda et al. 2011; Derogatis 1977). Although the SCL-90-R contains more items on MHD disturbances, we chose to only include the measures of affective disorders and those that are assumed to be directly affecting ones perceptions on difficult circumstances. PTSD-symptomatology was examined using the 22-item Self-Rating Inventory for PTSD (SRIP) with four-point Likert scales (Hovens et al. 2002). The Dutch norm tables were used to calculate the number of respondents with very severe problems indicative for mental disorders. The total SRIP score was used to determine probable cases of PTSD (cutoff = 52). Cronbach’s alphas of the entire sample’s baseline measurement (N = 1094) of all SCL-90-R subscales and SRIP were all > .82. Higher scores on SCL-90-R and SRIP scales indicate more symptoms. Probable PTSD was only measured among officers who recently experienced a PTE.

Potentially Traumatic Events

From 11 predefined events, such as handling traffic accidents, officers were asked to choose the most shocking one (if any), which they had experienced in the past 12 months. This set was based on earlier research (van der Velden et al. 2010; van der Velden et al. 2012). If their answer could not fit the answer options, respondents had the opportunity to fill in their own answer in a blank answering option.

Socio-demographic Variables

Age, gender, and educational level (i.e., primary school, lower secondary education, middle secondary education, higher secondary education, higher vocational education, master/doctorate) were all assessed at T0. In addition, respondents were asked about their working experience: years of service, rank (i.e., aspirant, invigilator, agent, principal agent, sergeant, inspector, chief inspector), and section (i.e., management, enforcement/emergency, investigation, intake and service, support, in training, else).

Training Evaluation

The training respondents in the experimental group were asked their appraisal of the training, at both 3 and 9 months follow-up. Respondents were asked to rate 15 statements on a four-point Likert scale, with answering options ranging from 0 “not at all applicable to me,” to 3 “very much applicable to me”. Items included the following: “I found the training useful,” “The training made me more resilient,” and “The training dampened the impact of police work.” A full overview of the 15 statements and the rating by respondents at both follow-ups can be found in Table 3.

Statistical Analyses

Respondents of the comparison group who reported being trained after T0 (n = 59) were excluded from the effect analysis. To investigate potential attrition bias, respondents participating in all surveys were compared to respondents who dropped out after baseline or the first follow-up measurement (n = 789) on all measurements included in the study. Non-response analyses were conducted using t tests and Cohen’s d, and chi-square tests.

The effect analyses were conducted using mixed-effect models using the data of experimental and comparison group respondents who participated at all three surveys (n Experimental = 138, n Comparison = 167). Outcome measures were eight continuous scales of psychological resilience and four of MHD’s. An interaction effect between a grouping variable (experimental versus comparison group) and a time variable (composed of three time moments) modeled the potential effectiveness of the training. When a significant group×time effect was found, we further examined the origin of this interaction effect; whether these group different patterns were found between baseline and the first follow-up measurement, and/or between the baseline and the second follow-up measurement. Furthermore, Cohen’s d was used to determine the effect size of any change over time within the experimental and comparison group (Lakens 2013). The mixed-effect models incorporated an auto-regressive covariance structure, which is considered to be the best fit to longitudinal data (Heck et al. 2013). The effect analyses were repeated for the sub groups of police officers in both the experimental and comparison group, who had experienced a PTE somewhere between 2 months before T0 and between T0 and T2 (n Experimental = 74, n Comparison = 96).

Lastly, the change in experimental group respondent evaluation of the training was compared between the first and second follow-up using a Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Results

Non-response Analyses and Characteristics Completers

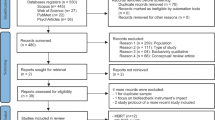

Figure 1 shows the response rate of both the experimental and comparison group across all three time points. Attrition rates between T0/T1 and T1/T2 within the experimental group were 59.4% and 47.7%, and within the comparison group 46.5% and 26.1%, respectively. As can be seen in Table 1, non-respondents were younger, had less years of service, and were of a lower rank as compared to respondents in both the experimental and comparison group (all: p ≤ .018). Only in the experimental group there was a significant difference in rank between the non-respondents and the respondents (p = .003). Assumption violations prohibited meaningful comparison of educational level.

The experimental and comparison group differed significantly in years of service. In addition, the comparison group had significantly (all: p < .05) higher scores on all MTQ-48 and RS-nl scales at T0 than the experimental group, except for RS-nl subscale “Acceptance of Self and Life.” Corresponding Cohen’s d effect sizes of the differences for the RS-nl total score, and for the “Personal competence” and “Dealing with difficult situations” subscales were .34, .36, and 35, respectively. Cohen’s d for the MTQ-48 total score and subscales of Challenge, Commitment and Interpersonal Confidence were .60, .40, .35, and .79, respectively. These findings show that especially with respect to Interpersonal Confidence, the comparison group had distinctly higher scores than the experimental group. Despite potential MST candidates being excluded due to severe MHD-related functioning disparities, no significant differences were found in MHD’s at T0. Within the total group, T0 differences of anxiety, depression, and hostility yielded Cohen’s d effect sizes of .16, .00, and 0.11, respectively, between the experimental and comparison group. Cohen’s d effect sizes of T0 scores differences of anxiety, depression, hostility, and PTSD were with the group with PTE experience: .08, .08, .10, and − .08, respectively, between the experimental and comparison group. Moreover, MHD’s were not very prevalent among both groups: less than 1% suffered from probable PTSD and less than 4% suffered from high levels of depression symptoms (Cf. van der Velden et al. 2013).

Course of Psychological Resilience and Mental Health Disturbances Among Total Experimental and Comparison Group

The scores on psychological resilience and mental health at T0, T1, and T2 of both the experimental and comparison total groups (completers) are presented in the upper half of Table 2. Mixed-effects models analyses showed that the comparison group had significantly higher scores on all MTQ-48 scales: the Total scale (F(1, 303.917) = 17.627, p = .000), and subscales of Challenge (F(1, 305.449) = 12.977, p = .000), Commitment (F(1, 304.627) = 14.205, p = .000), and Interpersonal Confidence (F(1, 303.836) = 31.064, p = .000). A significant group×time effect was found for Interpersonal Confidence (F(2, 431.182) = 7.064, p = .001): scores slightly increased (Cohen’s d = .22) in the experimental group and slightly decreased (Cohen’s d = − .18) in the comparison group between T0 and T1 (t(513.201) = − 3550, p = .000). For the other scales, no significant interaction effects were found. A similar pattern was found for the RS-nl scales: the comparison group had higher scores at T0 than the experimental group (Total score: F(1, 304.571) = 13.666, p = .000; Acceptance: F(1, 304.820) = 5.781, p = .017; Personal Competence: F(1, 305.121) = 14.264, p = .000; Dealing with Difficult Circumstances: F(1, 304.860) = 16.970, p = .000). No significant group×time effect was found for any RS-nl scale. None of the mental health outcome measures of anxiety, depression, hostility, or PTSD showed any significant group differences, change over time, or group×time interactions.

Course of Psychological Resilience and Mental Health Disturbances Among Experimental and Comparison Group Exposed to Potentially Traumatic Events

For scores of psychological resilience and mental health of both PTE sub groups at T0, T1, and T2, we refer to the lower half of Table 2. Again, the comparison group showed significant higher levels of psychological resilience, except for the RS-nl scale Acceptance (p = .169). Analyses among respondents exposed to PTEs showed two more significant interaction effects. There was a significant group×time effect for the MTQ-48 total scale (F(2, 211.885) = 4.980, p = .008) and the MTQ-48 scale Interpersonal Confidence (F(2, 273.188) = 9.551, p = .000). MTQ-48 total scores declined slightly (Cohen’s d = − .27) between T0 and T1 among the comparison group, while remaining stable (Cohen’s d = .26) among the experimental group (t(278.990) = − 3.150, p = .002). With respect to Interpersonal Confidence, scores of the comparison group declined slightly (Cohen’s d = − .23) between T0 and T1, while increasing slightly (Cohen’s d = .31) among the experimental group (t(260.736) = − 3.514, p = .001). Between T0 and T2, the experimental group also showed a slight increase (Cohen’s d = .24), while the comparison group remained stable (Cohen’s d = − .37) (t(184.591) = − 3.996, p = .000). A significant group×time effect was also found in the RS-nl scale Acceptance (F(2, 327.426) = 3.164, p = .044). Levels of Acceptance was stable (Cohen’s d = .01) among the experimental group between T0 and T2 while declining slightly (Cohen’s d = − .18) among the comparison group (t(165.893) = − 2.149, p = .033). For all other scales, no significant interaction effects were found. Due to very low levels of PTSD symptomology, we did not examine the course of PTSD symptoms among both groups. Again, the remaining mental health outcomes of anxiety, depression, and hostility showed no significant group differences, change over time, or group×time interactions.

We repeated the mixed models analyses among respondents of both groups with scores in the 30th percentile of the MTQ-48 and RS-nl. The results were almost similar (data not shown and available on request).

Training Appraisal

The outcomes of the appraisal of the training by trained police officers are presented in Table 3. Comparing differences between the first and second follow-up resulted in significant change in appraisal between the measurement moments for the statements: “training was applicable in work” and “potentially traumatic events are processed faster.” In the first statement, the number of respondents that did not agree, or agreed some, or very much diminished, while more respondents agreed little with this statement (p = .003). For the second statement, the number of respondents that agreed some or very much decreased, in favor of not agreeing or agreeing a little (p = .048). For all other statements, the number of respondents in each answer category was stable.

Discussion

In the present quasi-experimental study, we found no indications that 4-day MST (strongly) improved the psychological resilience or mental health of the participating Dutch police officers during the 9 months post-training, compared to police officers that did not participate in MST. Psychological resilience during this period appeared to be relatively stable among both groups, although psychological resilience was higher among the comparison group. Among the total study group (N = 305), a significant training effect was found for Interpersonal Confidence only. However, this finding is probably best explained as a statistical artifact. Since scores on Interpersonal Confidence were distinctly higher in the comparison group as compared to the experimental group, the observed increase of Interpersonal Confidence in the experimental group and decrease in the comparison group seem like scores regressing to the mean over time. Analyses among respondents exposed to potentially traumatic events (N = 170) showed some additional significant training effects with similar patterns: Acceptance of Self and Life, Interpersonal Confidence, and Total Score on the MTQ-48 showed significant change. However, changes in levels of psychological resilience according to the MTQ-48 and RS-nl scores were very small. Therefore these findings seem of little practical relevance. Furthermore, in the case of mental health disturbances, no group differences nor change over time was found, in both the total and PTE groups. However, whether the current training lacks usefulness is subject to other considerations of which the following are the most important: (1) little evidence of low levels of psychological resilience or mental health, (2) the usefulness of psychological resilience as a concept for stress management, and (3) training enrollment regardless of the potential problems of individual officers. We will discuss these matters further below.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no validated cutoff norms for the MTQ-48 and RS-nl that help to identify police officers with (too) low levels of psychological resilience. However, scores on both questionnaires in the current study question findings from earlier reports (Andersson Elffers Felix 2011) regarding the (lack of) psychological resilience of Dutch officers that initiated the development of the MST. It must be noted that the white paper report by Anderson Elffers Felix (2011) does not present any empirical evidence to corroborate the lack of psychological resilience, but rather makes inferences based on earlier research. When psychological resilience is actually measured among Dutch police officers, as in the current study, these inferences clearly do not hold. For example, the lowest MTQ-48 total mean measured at all time points among the experimental and comparison groups was 177.6 (range 48–240); for RS-nl this was 4.1 (range 1–5). At baseline, 98.3 and 86% had MTQ-48 scores of 144 or higher (cutoff when scores across items are neutral = 3) and 168 or higher (cutoff when scores across items are above neutral = 3.5), respectively. Furthermore, the prevalence levels of very high and probable clinical levels of anxiety, depression, hostility (all below 3%), and PTSD-symptomatology (all below 2%) were very low, which is in line with our findings on levels of psychological resilience and corroborated in recent research among police officers in the Netherlands (van Beek et al. 2013; van der Velden et al. 2013). One explanation for these findings on psychological resilience and mental health could be the rigorous police academy selection processes: about 90% of those applying to the officer training program is rejected (van der Velden et al. 2013). This may suggest that there was little room for improvement of resilience. However, the differences between trained and comparison group at the start of the training suggest that there was room for improvement among the trained respondents. Furthermore, the additional analyses among those with relatively low scores (scores in 30th percentile) did not change main outcomes. Therefore, the lack of increase in psychological resilience post-training in the experimental group is presumable due to lack of training efficacy. This is further corroborated by the training evaluation provided by respondents in the experimental group. At both follow-ups, a large majority of respondents felt that the training did little or nothing in adding to their ability to deal with the impact of police work (86.9 and 88.4%, respectively) and/or enhancing their resilience (84.0 and 84.7%). Furthermore, only a minority of participants felt they were taught new things (37.3 and 32.9%, respectively). These findings suggest that the training did not meet individual needs or problems.

It might appear sensible to find similarities between sports and policing, as they both require the ability to perform well under stressful conditions. However, it is also apparent that the main concern of athletes in stressful circumstances is not to safeguard the safety of themselves or others, as is the case for police officers. The absence of effects might be induced by the incorrectness of translating the athletes’ competitive circumstances, to the police circumstances of handling critical incidents. Furthermore, although psychological resilience is often at the conceptual core of stress management, it remains questionable whether this is an effective choice when aiming to improve the ability of the police work force, or similar professions like the military to deal with stressful situations. A recent study by Hystad et al. (2015) stressed group level stability of hardiness, a concept akin to psychological resilience, after 3 years of military training and thereby disputing the changeability of psychological resilience within the military population. In contrast, the study by McCraty et al. (2009) did find positive training effects, but focused more on other aspects such as coping, motivation, and/or positive outlook. Also, when comparing MST-like concepts in a broader field of occupations, such as teachers, managers, military, and the police, it shows that resilience enhancement can be achieved, but effects are small, and in half the cases too small to reach statistical significance according to Robertson et al. (2015). This is in line with our findings; some effects were found, but all effects sizes were small. In contrast to the current study, however, larger effects were found in a review (Robertson et al. 2015) which focused on well-being or mental health outcome measures, rather than psychosocial or performance outcome measures. Absence of substantial MHD prevalence in the current study might be the cause of not replicating this finding.

Another reason as to why the training yielded little to no effects could be found in the form of its delivery. The training was provided to police officers regardless of their individual needs or subjectively experienced problems. Furthermore, it was given to groups of police officers. A recent meta-analysis by Vanhove et al. (2015) examining the effectiveness of resilience building programs has shown that the individual approach yielded more long-term effects, when compared, among others, to training provided to groups. They also showed that programs targeted at problems experienced by the individual work better than so-called universal programs; training given to the entire population without consideration of individual needs or problems (Vanhove et al. 2015). A targeted training given to police officers that experience problems could also enhance efficiency of workforce enhancement efforts. For example, police leadership identifying cases of inadequate stress coping of police officers that require subsequent attention (Chapin et al. 2008). In the current sample and in the sample of van Beek et al. (2013), prevalence levels of serious MHDs were 10% at the highest. It would be more feasible and efficient to provide support to this smaller subset of officers.

However, additional analyses among the subgroup with relatively low levels of resilience showed similar outcomes as among the total group of respondents. Although we did not ask respondents the question if they thought that they needed this training (it was mandatory), relatively low levels may serve as an indication that their need was higher than among those with high levels of resilience. This finding and other results also raises questions about the theoretical background of the training. Besides the aspect of stability of resilience and possibilities to change resilience (see above), in this perspective attention must be paid to the following. The MST training tried to improve challenge, control, and confidence skills and used components developed in other trainings. Although our findings are in line with for example the recent review of Robertson et al. (2015), perhaps other (theoretical) models on learning and training are needed to be able to develop a resilience training that can improve these skills, especially among those who need it or exhibit low levels of resilience. One perhaps simple but important element might be the duration or intensity of the training. The MST consisted of three subsequent days and one meeting months later, (implicitly) assuming that the skills could best be learned or improved by a training of three subsequent days. The outcomes of other studies question this assumption. For instance, Arnetz et al. (2013) described a 10-week training (weekly 2 h sessions) aimed at enhancing control over stressful situations, which was expected to improve coping abilities. Hence, these abilities should support mental well-being of officers in the context of operational stressors. In contrast to MST, this intervention does show some small to moderate effects on for example sleep quality and mental health (Arnetz et al. 2013). The US military, to some extent a comparable population, has implemented the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program (Cornum et al. 2011). This continues resilience enhancement and maintenance program consists of tracking, supporting, and training resilience to enhance the mental and social well-being of soldiers and their spouses/family (Cornum et al. 2011; Vie et al. 2016). These two programs share the monitoring of the participants and prolonged efforts in enhancing resilience, and or not limited to a few days. As said, behavioral change will most likely occur when the change-effort is sensitive to the needs of the affected and anchorage of such behavior needs prolonged and intensive effort (Vanhove et al. 2015). Adopting this insight, i.e., another model of learning, might improve the effectiveness of a MST training among police officers with low levels of resilience.

Limitations of the Study

The current study does have certain limitations. We were unable to conduct a randomized controlled trial which is considered the “gold standard,” but a quasi-experimental design can be considered the second best and feasible design for examining the effects of such a training program according to Patterson et al. (2012). Additionally, since the training was provided to teams, conducting a randomized controlled trial, in which individual officers are randomly assigned to either an experimental or comparison group, might compromise ecological validity of the study. Team level randomization is hardly different from the current study, since team enrollment into MST is not based on either levels of psychological resilience nor MHDs, but rather on logistical issues. Therefore, selection bias based on psychological resilience or MHD’s is highly unlikely.

The training exclusion criteria based on seriously impeded functioning due to MHD could be a source of differences between the experimental and control groups. However, MHD was comparable between experimental and comparison group. The largest Cohen’s d for baseline MHD differences between the experimental and comparison group was .16 and thereby too small to suggest any substantial differences between the groups.

The comparison group in the current study did not undergo any intervention; placebo or “training as usual.” The results based on the comparison between the experimental and comparison group, therefore, was not attributable to training content, but was found in the distinction between being trained or not. However, when the conclusion is reached whether that delivering a training yields none too little effect, comparing an untrained group of police officers to a group of trained police officers should be considered sufficient proof. The trained officers remained unaffected by the training in their development of psychological resilience and/or mental health disturbances, since the development was comparable to their untrained colleagues.

Previous systematic reviews on resilience training stress that none of the individual studies on the topic were able to determine effectiveness of individual components, but provide an overall effect of the entire training. The current study is not different. However, for most types of training, including the one analyzed in the current study, training components are complementary to each other and therefore effectiveness of individual components is dependent on the availability of its complementary components. For example, the current training advances preparing, handling, and dealing with the aftermath of stressful events. Potential effects of solely focusing on better preparation for stressful events in a particular training might be offset by the absence of advancing in actual handling stressful events by officers.

Attrition occurred during follow-up measurements in both the experimental and the comparison group, especially among the experimental group after baseline. Higher attrition rates among experimental groups are not uncommon in health behavior change (HBC) trials (Crutzen et al. 2015). However, non-response analyses showed that attrition in the experimental and comparison group was barely associated with outcome measures of psychological resilience and MHDs.

Psychological resilience and mental health were assessed using self-report questionnaires. We did not conduct personal (clinical) interviews or use biological measures as for instance McCraty et al. (2009) did. We have no other sources of information, such as the perceptions of colleagues, superiors, or occupational physicians on the mental strength and/or mental health of the respondents in our study. Furthermore, we have no data on individuals’ potential needs or problems. It is possible that the MST is (more) effective for officers who experience needs or problems with respect to psychological resilience. Future studies should include questions assessing these needs or problems regardless of the inclusion criteria of the intervention.

Despite these characteristics and possible limitations, some strength should be stressed as well, such as the relatively large study sample, inclusion of several officer ranks/functions, using two different measures on psychological resilience, and the three-wave study design. As stressed in this review (Robertson et al. 2015), it is remarkable that most effect studies on resilience enhancement did not include resilience measures. To the best of our knowledge, there are no such studies thus far within law enforcement.

Practical Implications

The 4-day training yielded small effects in enhancing a very limited number of domains that are considered to be part of psychological resilience. But to conclude low efficacy of the training is subject to other considerations. The main premise of the course, the supposed limited psychological resilience and high prevalence of MHD’s among Dutch law enforcement, is very unlikely to hold when one considers the measured levels among officers in our study. Furthermore, it is unlikely that psychological resilience is useful as a central concept for enhancing the workforce, as, for example, rigorous selection methods make it unlikely that psychological resilience deficits are prevalent among officers. Lastly, the training was not sensitive to any problems individual officers might have. The current study underpins findings on effectiveness of resilience enhancement training for police officers. It showed the relative ineffectiveness of a group-based training not specifically targeted at individual problems or needs.

References

Andersson Elffers Felix (2011) De prijs die je betaalt…. Utrecht: AEF

Arnetz BB, Nevedal DC, Lumley MA, Backman L, Lublin A (2009) Trauma resilience training for police: psychophysiological and performance effects. J Police Crim Psychol 24(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-008-9030-y

Arnetz BB, Arble E, Backman L, Lynch A, Lublin A (2013) Assessment of a prevention program for work-related stress among urban police officers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 86(1):79–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-012-0748-6

Arrindell WA, Ettema JHM (1986) Manual for a multidimensional psychopathology indicator SCL-90. Swets & Zeitlinger/SwetsTest Publishers, Lisse

Backman L, Arnetz BB, Levin D, Lublin A (1997) Psychophysiological effects of mental imaging training for police trainees. Stress Medicine 13(1):43–48

Barton J, Vrij A, Bull R (2004) Shift patterns and hardiness: police use of lethal force during simulated incidents. J Police Crim Psychol 19(1):82–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02802577

Berg AM, Hem E, Lau B, Ekeberg Ø (2006) An exploration of job stress and health in the Norwegian police service: a cross sectional study. J Occup Med Toxicol 1(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-1-26

Brough P (2004) Comparing the influence of traumatic and organizational stressors on the psychological health of police, fire, and ambulance officers. Int J Stress Manag 11(3):227–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.11.3.227

Buwalda V, Draisma S, Smit J, Swinkels J, van Tilburg W (2011) Validering van twee meetinstrumenten voor routine outcome monitoring in de psychiatrie: de HORVAN-studie. Tijdschr Psychiatr 53(10):715–726

Chapin M, Brannen SJ, Singer MI, Walker M (2008) Training police leadership to recognize and address operational stress. Police Q 11(3):338–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611107307736

Charles LE, Slaven JE, Mnatsakanova A, Ma C, Violanti JM, Fekedulegn D, Burchfiel CM (2011) Association of perceived stress with sleep duration and sleep quality in police officers. J Emerg Ment Health 13(4):229–242

Cheong J, Yun I (2011) Victimization, stress and use of force among South Korean police officers. Polic: Int J Police Strateg Manag 34(4):606–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511111180234

Clough P, Earle K, Sewell D (2002) Mental toughness: the concept and its measurement. In: Cockerill IM (ed) Solutions in sport psychology. Thomson, London, pp 32–46

Collins PA, Gibbs ACC (2003) Stress in police officers: a study of the origins, prevalence and severity of stress-related symptoms within a county police force. Occup Med 53(4):256–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqg061

Cornum R, Matthews MD, Seligman ME (2011) Comprehensive soldier fitness: building resilience in a challenging institutional context. Am Psychol 66(1):4–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021420

Crutzen R, Viechtbauer W, Spigt M, Kotz D (2015) Differential attrition in health behaviour change trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health 30(1):122–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.953526

de Terte I, Stephens C, Huddleston L (2014) The development of a three part model of psychological resilience. Stress Health 30(5):416–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2625

Derogatis LR (1977) The SCL-90 Manual I: scoring, administration and procedures for the SCL-90. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Unit, Baltimore

Devilly GJ, Varker T (2013) The prevention of trauma reactions in police officers: decreasing reliance on drugs and alcohol. National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund (NDLERF). Retrieved from: http://www.ndlerf.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/monographs/monograph47.pdf

DiGangi JA, Gomez D, Mendoza L, Jason LA, Keys CB, Koenen KC (2013) Pretrauma risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 33(6):728–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.002

Heck RH, Thomas SL, Tabata LN (2013) Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS. Routledge, Abingdon

Hovens J, Bramsen I, Van der Ploeg H (2002) Zelfinventarisatielijst voor de posttraumatische stressstoornis. Tijdschr Klin Psychol 176:180

Hystad SW, Olsen OK, Espevik R, Säfvenbom R (2015) On the stability of psychological hardiness: a three-year longitudinal study. Mil Psychol 27(3):155–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000069

Kobasa SC, Maddi SR, Kahn S (1982) Hardiness and health: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol 42(1):168–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.168

Kop N, Euwema M, Schaufeli W (1999) Burnout, job stress and violent behaviour among Dutch police officers. Work Stress 13(4):326–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379950019789

Lakens D (2013) Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

LeBlanc VR, Regehr C, Jelley RB, Barath I (2008) The relationship between coping styles, performance, and responses to stressful scenarios in police recruits. Int J Stress Manag 15(1):76–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.15.1.76

Maguen S, Metzler TJ, McCaslin SE, Inslicht SS, Henn-Haase C, Neylan TC, Marmar CR (2009) Routine work environment stress and PTSD symptoms in police officers. J Nerv Ment Dis 197(10):754–760. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b975f8

McCraty R, Tomasino D, Atkinson M, Sundram J (1999) Impact of the HeartMath self-management skills program on physiological and psychological stress in police officers. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of Heartmath

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Lipsenthal L, Arguelles L (2009) New hope for correctional officers: an innovative program for reducing stress and health risks. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 34(4):251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-009-9087-0

McGeary DD (2011) Making sense of resilience. Mil Med 176(6):603–604. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00480

Miller L (2008) Stress and resilience in law enforcement training and practice. Int J Emerg Ment Health 10(2):109–124

Mumford EA, Taylor BG, Kubu B (2015) Law enforcement officer safety and wellness. Police Q 18(2):111–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611114559037

Papazoglou K, Andersen JP (2014) A guide to utilizing police training as a tool to promote resilience and improve health outcomes among police officers. Traumatol: Int J 20(2):103–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099394

Patterson G, Chung I, Swan PG (2012) The effects of stress management interventions among police officers and recruits. Campbell Syst Rev 8(7). https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2012.7

Pavšič Mrevlje T (2014) Coping with work-related traumatic situations among crime scene technicians. Stress Health 32(4):374–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2631

Peñalba V, McGuire H, Leite JR (2008) Psychosocial interventions for prevention of psychological disorders in law enforcement officers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005601.pub2

Politieacademie (2012a). Mentale Weerbaarheid: Training Mentale Kracht

Politieacademie (2012b) Trainershandleiding Mentale Kracht 2.0

Politieacademie (2012c) Visiedocument Training Professionele Weerbaarheid: Mentale Kracht

Portzky M (2008) RS-nl Resilience Scale–Nederlandse versie. Handleiding. Harcourt Test Publishers

Portzky M, Audenaert K, De Bacquer D (2009) Resilience in de Vlaamse en Nederlandse algemene populatie. Tijdschr Klin Psychol 39(3):183–193

Ranta RS, Sud A (2008) Management of stress and burnout of police personnel. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol 34(1):29–39

Robertson IT, Cooper CL, Sarkar M, Curran T (2015) Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: a systematic review. J Occup Organ Psychol 88(3):533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12120

van Beek I, Taris T, Schaufeli W (2013) De psychosociale gezondheid van politiepersoneel. Retrieved from https://www.wodc.nl/images/2228-volledige-tekst_tcm44-517961.pdf

van der Velden PG, Kleber RJ, Grievink L, Yzermans JC (2010) Confrontations with aggression and mental health problems in police officers: the role of organizational stressors, life-events and previous mental health problems. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Policy 2(2):135–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019158

van der Velden PG, van Loon P, Benight CC, Eckhardt T (2012) Mental health problems among search and rescue workers deployed in the Haïti earthquake 2010: a pre–post comparison. Psychiatry Res 198(1):100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.017

van der Velden PG, Rademaker AR, Vermetten E, Portengen M-A, Yzermans JC, Grievink L (2013) Police officers: a high-risk group for the development of mental health disturbances? A cohort study. BMJ Open 3(1):e001720. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001720

Vanhove AJ, Herian MN, Perez AL, Harms PD, Lester PB (2015) Can resilience be developed at work? A meta-analytic review of resilience-building programme effectiveness. J Occup Organ Psychol 89(2):278–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12123

Vie LL, Scheier LM, Lester PB, Seligman ME (2016) Initial validation of the US Army Global Assessment Tool. Mil Psychol 28(6):468–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000141

Violanti JM, Aron F (1993) Sources of police stressors, job attitudes, and psychological distress. Psychol Rep 72(3):899–904. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3.899

Wagnild GM, Young HM (1993) Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas 1(2):165–178

Wang Z, Inslicht SS, Metzler TJ, Henn-Haase C, McCaslin SE, Tong H, Marmar CR (2010) A prospective study of predictors of depression symptoms in police. Psychiatry Res 175(3):211–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.010

Williams V, Ciarrochi J, Patrick Deane F (2010) On being mindful, emotionally aware, and more resilient: longitudinal pilot study of police recruits. Aust Psychol 45(4):274–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060903573197

Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J (2011) A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 9(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-8

Zach S, Raviv S, Inbar R (2007) The benefits of a graduated training program for security officers on physical performance in stressful situations. Int J Stress Manag 14(4):350–369. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.4.350

Funding

This work was supported by the Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum (WODC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Meulen, E., Bosmans, M.W.G., Lens, K.M.E. et al. Effects of Mental Strength Training for Police Officers: a Three-Wave Quasi-experimental Study. J Police Crim Psych 33, 385–397 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-017-9247-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-017-9247-8