Abstract

Purpose of Review

An increased frequency of autoimmunity in children with Down syndrome (DS) is well described but few studies have investigated the underlying mechanisms. Recent immune system investigation of individuals with DS may shed light on the increased risk of autoimmune conditions including type 1 diabetes.

Recent Findings

Diagnosis of type 1 diabetes is accelerated in children with DS with 17% diagnosed at, or under, the age of 2 years compared with only 4% in the same age group in the general population. Counterintuitively, children with DS and diabetes have less human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-mediated susceptibility than age-matched children with autoimmune diabetes from the general population. Early onset of diabetes in DS is further highlighted by the recent description of neonatal cases of diabetes which is autoimmune but not HLA associated. There are two potential explanations for this accelerated onset: (1) an additional chromosome 21 increases the genetic and immunological risk of autoimmune diabetes or (2) there are two separate aetiologies in children with DS and diabetes.

Summary

Autoimmunity in DS is an under-investigated area. In this review, we will draw on recent mechanistic studies in individuals with DS which shed some light on the increased risk of autoimmunity in children with DS and consider the current support for and against two aetiologies underlying diabetes in children with DS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Therapeutic strategies targeting the underlying mechanisms of autoimmunity may prove of great clinical value: a recent study demonstrated that autoimmune disease was the underlying or contributory cause in 3.4% of deaths in females after the first year of life [1]. It is clear that common mechanisms underlie these diseases: genome-wide association studies (GWAS) emphasise the importance of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and suggest roles for several T cell suppressor genes, yet mechanistic data are limited. Immunological insights into susceptibility to autoimmunity are increasing from an unexpected avenue, autoimmune pathways in children with Down syndrome (DS).

DS is a relatively common condition affecting over 300,000 people in the USA and 30,000 in the UK and ranging from 1:700 to 1:1000 live births [2, 3]. Those born with DS have increased risk of many complex health conditions including congenital heart defects, leukaemia, dementia and autoimmune conditions [4].

Autoimmunity in DS

Hypothyroidism is present in one-third of children with DS (although some may result from thyroid hypoplasia) [5] and celiac disease-associated antibodies in 10% [6, 7]. A considerably increased risk of developing clinically diagnosed type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been consistently reported in children with DS [8,9,10,11]. In a questionnaire-based study of 20,362 patients with DS in the UK and USA, the prevalence of diabetes diagnosed before age 20 in the DS population was 6 times higher than expected [8]. A more recent population-based study of the prevalence of T1D in DS in Denmark demonstrated a 4-fold increased risk of T1D in children with DS [12]. In these studies of diabetes in DS, no attempts were made to systematically characterise diabetes in DS.

Autoimmune Diabetes in DS

Autoantibodies to islet antigens, insulin (IAA) [13], glutamate decarboxylase (GADA) [14], islet antigen-2 (IA-2A) [15, 16] and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8A) [17] and more recently tetraspanin-7 [18] are the most reliable markers of humoral activity in autoimmune diabetes and combinations of two or more islet autoantibodies remain the best predictors of the condition [19]. As islet autoimmunity evolves, there is typically spreading of reactivity to different target autoantigens and epitopes. IAA are often the first autoantibodies to be detected in infancy, followed by GADA [20, 21], while IA-2A and ZnT8A tend to appear later.

To determine whether islet autoantibodies are more common in children with DS compared with the general population, we analysed the frequency of T1D-associated islet autoantibodies in 106 children with DS and found evidence of 2 or more antibodies in 6/106 (5.7%) compared to 0.28% in an age-matched control population (p < 0.001). Intriguingly, the titres of antibodies to GADA were particularly high in some of these children [22•].

These data provide immunological evidence that autoimmune diabetes is increased in children with DS. It has been suggested that diabetes in DS generally presents early in life; one study from the 1960s showed a peak onset at 8 years of age, compared with 14 years in contemporary cases of childhood diabetes [23]. In a more recent study of DS and T1D by the authors, 22% had developed diabetes by the age of 2 years, as compared to 7% of those from the general diabetes population [24••]. This indicates that onset is accelerated in DS children compared with children with T1D in the general population. Concerns that this pattern was caused by selection bias were alleviated by a study from the Diabetes-Patienten-Verlaufsdaten, a longitudinal follow-up database, which collects data from 298 German and Austrian diabetes centres [25]. Their data from over 42,000 children with diabetes also showed a biphasic pattern in age at onset in 159 children with DS and diabetes. Of interest is the observation in this study that children with DS and diabetes used less insulin but showed better glycaemic control. Many studies of those diagnosed with DS and diabetes aimed to calculate the frequency of both conditions (and other forms of autoimmunity) co-occurring. A list of published populations is outlined in Table 1.

Neonatal Diabetes in Children with DS

Johnson and colleagues [26••] observed that among a unique cohort of 1522 children diagnosed with permanent neonatal diabetes diagnosed before the age of 6 months, 13 (0.9%) had Down syndrome, some 6.7-fold higher than the expected population frequency of 12.6 per 10,000. None of the children tested positive for recognised mutations for neonatal diabetes. Samples were available for islet autoantibody testing on 9 participants with time from diagnosis ranging from 4 months to 10 years. Of these, four were positive for GADA. Using a polygenic T1D risk score dominated by HLA-mediated risk [27], DS cases with neonatal diabetes did not have increased risk. In addition, four of the 13 (31%) were positive for the protective HLA DR15-DQB1*0602 haplotype which is observed in only 1% of type 1 diabetes cases in the general population.

Heterogeneity of diabetes in DS is supported by genetic studies. The frequency of diabetes-associated high-risk HLA haplotypes in children with DS and T1D (diagnosed before the age of 21) was examined [24••]. There was an excess of diabetes-associated HLA class II genotypes in children with DS and T1D compared to age and sex-matched healthy controls (p < 0.001) indicating that, as might be expected, autoimmune diabetes in DS shares the same HLA susceptibility as T1D in the general population. DS children with T1D were however less likely to carry the highest-risk genotype DR4-DQ8/DR3-DQ2 than children with T1D from the general population (p = 0.01) and more likely to carry low-risk (DR2-DQ6/X or X/X) genotypes (p < 0.0001).

In summary, therefore, clinical diagnosis of diabetes in children with DS appears accelerated compared with the general population. In type 1 diabetes, children who develop the condition in early life (for instance under the age of 5 years) have increased HLA-mediated susceptibility [28]. Why do children with DS and diabetes have less HLA risk? One possible explanation is that two different aetiologies are underlying the increased prevalence of diabetes in DS; one HLA mediated and one which is not. Larger cohorts of individuals with DS and diabetes with samples available at diagnosis for islet autoantibody screening are required to address this question.

Pancreatic Pathology in DS and Diabetes

Studies of the pancreas in individuals with DS and diabetes are extremely rare. In the seminal study of pancreatic pathology in type 1 diabetes, however, Foulis et al. described three cases of DS and diabetes [29]. One was a 14-year-old boy who had diabetes for several years and another, a 12-year-old with recent-onset diabetes: both showed evidence of lymphocytic infiltration with the absence of insulin staining in the 14-year-old boy, typical of T1D. The third child, however, diagnosed with diabetes at 18 months whose pancreas was analysed within 2 weeks of diagnosis of diabetes displayed normal insulin staining with no morphological abnormality. This might add evidence to the suggestion that there are two aetiologies of diabetes in children with DS.

Butler and colleagues investigated whether the increased frequency of diabetes in DS was due to congenital defects in beta cells. Autopsy pancreas from individuals with DS and age-matched control subjects were examined and no difference was observed in the fractional islet beta-cell area between the two groups [40].

Immune Development in DS

Immune dysfunction in DS is not surprising given that the DS thymus is small with an abnormal structure, even in the neonate, and shows a decreased proportion of phenotypically mature thymocytes [31,41,43]. T cell receptor (TCR) excision circle counts suggest that proportions of recent thymic emigrants in peripheral blood are decreased [44, 45]. Absolute numbers of T lymphocytes are also decreased in the DS neonate as well as the proliferative response to phytohemagglutinin, implying a deficient reaction to antigenic stimulation, but counts gradually approach those of normal children over time [46, 47]. Humoral immune-deficiencies have also been described in DS. In most of these reports, the number of B lymphocytes was found to be decreased and their ability to produce antibodies was diminished [46]. In addition, levels of CD4+ (T helper/inducer) were reduced and levels of CD8+ (T suppressor/cytotoxic) lymphocytes increased as compared with healthy subjects [46, 48, 49, 50]. As well as deficiencies in the adaptive immune response, the innate immune response is also altered in DS. In particular, it has been reported that natural killer (NK) cell frequency is altered and several studies have described a significant increase of cells possessing the low NK activity phenotype in DS, with an associated decrease of cells with the intermediate and high NK activity phenotype [51, 52].

Recent in-depth characterisations by Espinosa and colleagues suggest a state of chronic inflammation in DS, with consistent interferon overexpression and hyperactivation [43,53,55]. Proteomic analysis of DS plasma detected 299 proteins differentially regulated compared with controls with increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, VEGF-A, MCP-1, IL-22 and TNF-α and downregulation of proteins involved in immune control [53•]. Interestingly, functional analysis of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells showed those with DS were less sensitive to T-reg suppression [54••]. Large-scale mass cytometry analyses did not link the myeloid compartment shift towards inflammation and over-activation of NK and cytotoxic T cells to existing comorbidities suggesting a high basal inflammatory environment in DS [55••]. Reduced sensitivity to regulation and an inflammatory state without a clinical diagnosis of autoimmunity suggests compromised central tolerance in DS. Interestingly, a type 1 interferon transcriptional signature has been shown to precede autoimmunity in children genetically at risk of type 1 diabetes [56]. The role of interferons in T1D has been well-reviewed by Lombardi et al. [57]. Taken together, observations of heightened inflammation in individuals with DS and those genetically at risk of type 1 diabetes may indicate a common mechanism underlying autoimmunity in DS.

Environmental Factors in Down Syndrome

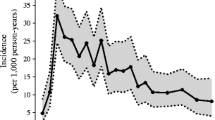

Children with Down Syndrome have a lower gestational age and a lower birth weight after 38 weeks compared to the general population [58]. Early birth has also been associated with T1D. Of 3,834,405 UK children under the age of 12 years, 2969 had a subsequent hospital diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in childhood. Children born preterm (<37 weeks) or early term (37-38 weeks) had a significantly higher incidence of subsequent type 1 diabetes than full term children (39-40 weeks) (HR 1.19 [95% CI 1.03, 1.38] and 1.27 [95% CI 1.16, 1.39], respectively). However low birthweight was not associated with future T1D, although higher birthweight was. This might suggest that factors associated with early birth but not birthweight may be important in DSD [59]. In studies of children genetically at risk for developing T1D, early life infections were associated with initiation of autoimmunty [60, 61]. Gastrointestinal infection and islet autoimmunty risk were dependent on feeding practices and weaning [61]. A large Norwegian general population study found that early life hopsitalisation with gastrointestinal infection increased risk of T1D but not infections not requiring hospitalisation or antibiotic use, [62]. In DS, children are more likely to be hosptialised due to infection and pneumonia is one of the major risk factors for motality [63, 64].

The development of the gut microbiome is modulated through early life feeding practices with the strongest differences seen in those who are breast-fed [65]. In children with early-onset T1D the gut micobiome has reduced diversity with an altered taxonomic profile [66]. Gut dysbiosis and immune barrier modulation with increased permeability was seen in a cohort of children with multiple islet autoantibodies [67]. The microbiome in DS has only been investigated in adulthood and was comparable to controls [68]. An important question remains on how differences in early life alter the gut microbiome in DS and how this, along with an immune system primed for inflammation could accelerate T1D.

Genetic Strategies

Ninety-five percent of Down syndrome cases result from maternal non-disjunction with the remaining 5% caused by other chromosomal anomalies, particularly translocations. A region described as the Down syndrome critical region (DSCR) has been identified as key to the phenotypes associated with DS (Fig. 1). The study of individuals with partial trisomy 21 and other chromosome 21 rearrangements associated with clinical features of DS could identify genomic regions associated with specific phenotypes. The method of choice for high-resolution mapping to identify genomic rearrangements resulting in different copy numbers is array comparative genome hybridisation (aCGH). A study of 30 cases with different DS-related chromosome 21 rearrangements analysed by aCGH to refine genotype-phenotype mapping showed susceptibility regions for 25 clinical DS phenotypes (not including autoimmunity) [69].

Overexpression of candidate genes on chromosome 21 represents a plausible hypothesis for DS-associated phenotypes, but studies using gene expression arrays indicate that there is not an overall 50% increase in expression of chromosome 21 genes but rather that overexpression in different organs determines disease associations [70]. In the first extensive study of its kind [71], gene expression variation was analysed in 14 lymphoblastoid and 17 fibroblast cell lines from individuals with DS and an equal number of controls; 100 and 106 chromosome 21 genes, and 23 and 26 non-chromosome 21 genes respectively, were examined. Only 39% and 62% of chromosome 21 genes in lymphoblastoid and fibroblast cells, respectively, showed a significant difference between DS and normal samples. This emphasises the tissue-specific effects of gene dosage imbalance and indicates that each DS phenotype is likely to have a distinct mRNA expression “signature”.

In our earlier studies of Down syndrome and diabetes, data on clinical diagnosis of other autoimmune diseases were available on 92 subjects. Of these, 68 (74%) had coexisting thyroid disease and 11 (14%) had coexisting celiac disease. Seven of 92 (8%) had coexisting diagnoses of diabetes and thyroid and celiac disease. The frequency of HLA class II DRB1*03 was significantly increased in this group compared to 270 sex and age-matched children with type 1 diabetes alone (p = 0.002). One of the common pathways of autoimmunity in DS, therefore, appears to be mediated through HLA DR3 as has been shown for multiple autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes [72•]. A second is likely to be the Ubiquitin-associated and SH3 domain-containing A (UBASH3A). GWAS of 2496 multiplex T1D families from the Type 1 Genetics Consortium identified a chromosome 21 type 1 diabetes-associated locus 21q22.3 associated with T1D [73] which has been replicated [74]. This locus was also independently associated with susceptibility to coeliac disease (P = 0.009) [75]. The only gene in the corresponding region of linkage disequilibrium is UBASH3A, alternatively known as suppressor of T cell signalling 2 (STS-2), which comprises 15 exons, spans 40 kb and is expressed in spleen, bone marrow and peripheral blood lymphocytes including B cells and T cells [76]. To ensure that T cells are not inappropriately activated, signalling pathways downstream of the TCR are subject to multiple levels of positive and negative regulation. UBASH3A (STS-2) negatively regulates TCR signalling. Peripheral T lymphocyte activation in response to TCR/CD3 stimulation is known to be reduced in type 1 diabetic patients. UBASH3A is, therefore, a good candidate to contribute to the increased frequency of autoimmune disease including autoimmune diabetes in DS. Concannon and colleagues recently reported that UBASH3A attenuates NF-kB signal transduction upon TCR stimulation showing that UBASH3A is potentially causal in T1D [77•].

It has long been hypothesized that 3 copies of the chromosome 21 gene product AIRE that regulates ectopic expression of tissue-specific antigens in thymic medullary epithelial cells, crucial for thymic T cell selection, may underlie the increased frequency of autoimmunity in DS children, but this is counterintuitive. Rare mutations resulting in reduced function of Aire cause aggressive autoimmunity [78]. Analysis of protein and gene expression in surgically removed thymi from 14 DS patients compared with 42 age-matched controls has thrown some light on this conundrum. Results showed reduced expression of Aire in DS thymi [79], and this has been confirmed by other studies [78, 80].

As discussed earlier, type 1 interferon responses may pre-set the immune system towards autoimmunity in individuals with DS. Intriguingly, therefore, 4 of 6 interferon receptor subunits are encoded on chromosome 21 [81]. Although not identified as common variants associated with T1D in GWAS studies, they may be over-expressed in individuals with DS helping to create the underlying autoimmune environment. Further studies of these genes in DS and autoimmunity are warranted.

A gene on chromosome 21q22.13, within the DSCR, is dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation kinase 1a (DYRK1A) which catalyses its autophosphorylation on serine/threonine and tyrosine residues.

DYRK1A appears to play a key role in the signalling pathway that regulates cell proliferation including in brain development. While most research on this enzyme has focused on its potential role in cognitive impairment in DS, it has recently become clear that this kinase reciprocally regulates the differentiation of proinflammatory Th17 cells and regulatory T cells [82••], a crucial immunological balance in T1D. Chemical inhibition of DYRK1A with harmine enhanced differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) from murine CD4+ naive T cells. Newly generated Tregs were able to suppress the proliferation of CD4+ effector cells stimulated with anti CD3/CD28. DYRK1A links mechanisms underlying cognitive and autoimmune impairments in DS.

Conclusions

Many questions remain regarding the increased frequency of autoimmunity in DS. There is growing evidence for interferon hyperactivity which may mean that the immune balance is weighted towards autoimmunity even in young children with DS. It remains unclear why some develop autoimmunity and others do not. We have therefore initiated the Feeding and Autoimmunity in Down Syndrome Evaluation study (FADES) [83], a longitudinal birth cohort of children with DS, which will be key to determining early life impacts on risk of progression to autoimmunity in DS.

Abbreviations

- aCGH:

-

Array comparative genome hybridisation

- DS:

-

Down syndrome

- DSD:

-

Down syndrome and diabetes

- DSCR:

-

Down syndrome critical region

- GADA:

-

Autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- IAA:

-

Insulin autoantibodies

- IA-2A:

-

Autoantibodies to IA-2

- NK:

-

Natural killer

- STS-3:

-

Suppressor of T cell signalling 2

- T1D:

-

Type 1 diabetes

- TCR:

-

T-cell receptor

- UBASH3A:

-

Ubiquitin-associated and SH3 domain-containing A

- ZnT8A:

-

Autoantibodies to zinc transporter 8

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Thomas SL, Griffiths C, Smeeth L, Rooney C, Hall AJ. Burden of mortality associated with autoimmune diseases among females in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2279–87.

De Graaf G, Buckley F, Skotko BG. Estimates of the live births, natural losses, and elective terminations with down syndrome in the United States. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167(4):756–67.

Steele J, Stratford B. The United Kingdom population with down syndrome: present and future projections. Am J Ment Retard. 1992;99(6):664–82.

Startin C, D’Souza H, Ball G, Hamburg S, Hithersay R, Hughes K, et al. Health comorbidities and cognitive abilities across the lifespan in down syndrome. J Neurodev Disord. 2020;12(1):4.

Karlsson B, Gustafsson J, Hedov G, Ivarsson SA, Anneren G. Thyroid dysfunction in Down's syndrome: relation to age and thyroid autoimmunity. 1998;79(3):242–5.

Book L, Hart A, Black J, Feolo M, Zone J, Neuhausen S. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of celiac disease in downs syndrome in a US study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98(1):70–4.

Sanchez--Albisua I, Storm W, Wascher I, Stern M. How frequent is coeliac disease in Down syndrome? 2002;161(12):683–4.

Milunsky A, Neurath P. Diabetes mellitus in Down's syndrome. Arch Environ Health. 1968;17(3):372–6.

Jeremiah DE, Leyshon GE, Francis TRHWS, Elliott RW. Down's Syndrome and Diabetes. 1973;3(04):455.

Van Goor JC, Massa GG, Hirasing R. Increased incidence and prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Down's syndrome. 1997;77(2):186.

Anwar A, Walker J, Frier B. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and Down's syndrome: prevalence, management and diabetic complications. Diabet Med. 1998;15(2):160–3.

Bergholdt R, Eising S, Nerup J, Pociot F. Increased prevalence of Down's syndrome in individuals with type 1 diabetes in Denmark: a nationwide population-based study. Diabetologia. 2006;49(6):1179–82.

Palmer J, Asplin C, Clemons P, Lyen K, Tatpati O, Raghu P et al. Insulin antibodies in insulin-dependent diabetics before insulin treatment. 1983;222(4630):1337–1339.

Baekkeskov S, Aanstoot H-J, Christgai S, Reetz A, Solimena M, Cascalho M et al. Identification of the 64K autoantigen in insulin-dependent diabetes as the GABA-synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase. 1990;347(6289):151–156.

Hawkes CJ, Wasmeier C, Christie MR, Hutton JC. Identification of the 37-kDa antigen in IDDM as a tyrosine phosphatase-like protein (Phogrin) related to IA-2. 1996;45(9):1187–1192.

Bearzatto M, Naserke H, Piquer S, Koczwara K, Lampasona V, Williams A et al. Two distinctly HLA-associated contiguous linear epitopes uniquely expressed within the islet antigen 2 molecule are major autoantibody epitopes of the diabetes-specific tyrosine phosphatase-like protein autoantigens. 2002;168(8):4202–8.

Wenzlau JM, Juhl K, Yu L, Moua O, Sarkar SA, Gottlieb P, et al. The cation efflux transporter ZnT8 (Slc30A8) is a major autoantigen in human type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(43):17040–5.

McLaughlin KA, Richardson CC, Ravishankar A, Brigatti C, Liberati D, Lampasona V, et al. Identification of tetraspanin-7 as a target of autoantibodies in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65(6):1690–8.

Bingley PJ, Bonifacio E, Williams AJK, Genovese S, Bottazzo GF, Gale EAM. Prediction of IDDM in the general population: strategies based on combinations of autoantibody markers. Diabetes. 1997;46(11):1701–10.

Ziegler AG, Hummel M, Schenker M, Bonifacio E. Autoantibody appearance and risk for development of childhood diabetes in offspring of parents with type 1 diabetes: the 2-year analysis of the German BABYDIAB study. Diabetes. 1999;48(3):460–8.

Rewers M, Hyöty H, Lernmark Å, Hagopian W, She J-X, Schatz D, et al. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study: 2018 Update. Current Diabetes Reports. 2018:18(12).

Gillespie K, Dix R, Williams A, Newton R, Robinson Z, Bingley P, et al. Islet autoimmunity in children with down's syndrome. Diabetes. 2006;55(11):3185–8. The first study to demonstrate an increased frequency of islet autoimmunity in children with DS.

Burch P, Milunsky A. Early-onset diabetes mellitus in the general and down's syndrome populations. Genetics, Ætiology, and Pathogenesis Lancet. 1969;293(759):554–8.

Aitken R, Mehers K, Williams A, Brown J, Bingley P, Holl R, et al. Early-onset, coexisting autoimmunity and decreased HLA-mediated susceptibility are the characteristics of diabetes in down syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1181–5. This paper shows that individuals with Down syndrome and diabetes also have a very high frequency of coeliac and thyroid autoimmunity, early onset of type 1 diabetes and decreased HLA mediated risk.

Rohrer TR, Hennes P, Thon A, Dost A, Grabert M, Rami B, et al. Down’s syndrome in diabetic patients aged <20 years: an analysis of metabolic status, glycaemic control and autoimmunity in comparison with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53(6):1070–5. Detailed characterisation of diabetes in individuals with Down syndrome with diabetes among a very large population of German and Austrian children with diabetes. Demonstrates early onset of diabetes in some and good glycaemic control overall.

Johnson MB, De Franco E, Greeley SAW, Letourneau LR, Gillespie KM, Wakeling MN, et al. Trisomy 21 is a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes that is autoimmune but not hla associated. Diabetes. 2019;68(7):1528–35. The first report of neonatal diabetes in children with Down syndrome.

Oram R, Patel K, Hill A, Shields B, McDonald T, Jones A, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(3):337–44.

Caillat-Zucman S, Garchon HJ, Timsit J, Assan R, Boitard C, Djilali-Saiah I, et al. Age-dependent HLA genetic heterogeneity of type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Investig. 1992;90(6):2242–50.

Foulis AK, Liddle CN, Farquharson MA, Richmond JA, Weir RS. The histopathology of the pancreas in type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: a 25-year review of deaths in patients under 20 years of age in the United Kingdom. Diabetologia. 1986;29(5):267–74.

Rabinowe SL, Rubin IL, George KL, Adri MN, Eisenbarth GS. Trisomy 21 (Down's syndrome): autoimmunity, aging and monoclonal antibody-defined T-cell abnormalities. J Autoimmun. 1989;2(1):25–30.

Griffin ME, Fulcher T, Nikookam K, Crowley J, Firth RG, O'Meara NM. Down's syndrome, IDDM, and hypothyroidism. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(7):1202–3.

Shield JP, Wadsworth EJ, Hassold TJ, Judis LA, Jacobs PA. Is disomic homozygosity at the APECED locus the cause of increased autoimmunity in Down's syndrome? Arch Dis Child. 1999;81(2):147–50.

Aktay AN, Lee PC, Kumar V, Parton E, Wyatt DT, Werlin SL. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of celiac disease in juvenile diabetes in Wisconsin. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(4):462–5.

Makovi H, Soltesz G, Hermann R. Clinical heterogeneity of childhood diabetes in Baranya county. Orv Hetil. 2002;143(44):2489–92.

Kota SK, Meher LK, Jammula S, Kota SK, Modi KD. Clinical profile of coexisting conditions in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Metabo Syndr. 2012;6(2):70–6.

Schmidt F, Kapellen TM, Wiegand S, Herbst A, Wolf J, Frohlich-Reiterer EE, et al. Diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents with genetic syndromes. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal. German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2012;120(10):579–85.

Taggart L, Coates V, Truesdale-Kennedy M. Management and quality indicators of diabetes mellitus in people with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res : JIDR. 2013;57(12):1152–63.

Aversa T, Valenzise M, Corrias A, Salerno M, Iughetti L, Tessaris D, et al. In children with autoimmune thyroid diseases the association with down syndrome can modify the clustering of extra-thyroidal autoimmune disorders. J Pediatr Endocr Met : JPEM. 2016;29(9):1041–6.

Abdulrazzaq Y, El-Azzabi TI, Al Hamad SM, Attia S, Deeb A, Aburawi EH. Occurrence of hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and celiac disease in emirati children with down's syndrome. Oman Med J. 2018;33(5):387–92.

Butler A, Sacks W, Rizza R, Butler P. Down syndrome-associated diabetes is not due to a congenital deficiency in beta cells. Journal of the Endocrine Society. 2017;1(1):39–45.

Murphy M, Epstein LB. Down syndrome (trisomy 21) thymuses have a decreased proportion of cells expressing high levels of TCRα,β and CD3. 1990;55(3):453–467.

Levin S, Schlesinger M, Handzel Z, Hahn T, Altman Y, Czernobilsky B, et al. Thymic deficiency in down’s syndrome. Pediatrics. 1979, 63(80).

Larocca L, Lauriola L, Ranelletti F, Piantelli M, Maggiano N, Ricci R, et al. Morphological and immunohistochemical study of down syndrome thymus. Am J Med Genet. 1990;7:225–30.

Bloemers B, Bont L, de Weger R, Otto S, Borghans J, Tesselaar K. Decreased thymic output accounts for decreased naive T cell numbers in children with down syndrome. J Immunol. 2011;186(7):4500–7.

Prada N, Nasi M, Troiano L, Roat E, Pinti M, Nemes E, et al. Direct analysis of thymic function in children with Down's syndrome. Immunity and Ageing. 2005:16(2).

de Hingh Y, van der Vossen P, Gemen E, Mulder A, Hop W, Brus F, et al. Intrinsic abnormalities of lymphocyte counts in children with down syndrome. J Pediatr. 2005;147(6):744–7.

Burgio GR, Lanzavecchia A, Maccario R, Vitiello A, Plebani A, Ugazio AG. Immunodeficiency in Down's syndrome: T-lymphocyte subset imbalance in trisomic children. Clin Exp Immunol. 1978;33(2):298–301.

Cuadrado E, Barrena MJ. Immune dysfunction in down's syndrome: primary immune deficiency or early senescence of the immune system? Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;78(3):209–14.

Raziuddin S, Elawad ME. Immunoregulatory CD4+ CD45R+ suppressor/inducer T lymphocyte subsets and impaired cell-mediated immunity in patients with Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;79(1):67–71.

Scotese I, Gaetaniello L, Matarese G, Lecora M, Racioppi L, Pignata C. T Cell activation deficiency associated with an aberrant pattern of protein tyrosine phosphorylation after CD3 perturbation in down's syndrome. 1998;44(2):252–258.

Cossarizza A, Monti D, Montagnani G, Ortolani C, Masi M, Zannotti M, et al. Precocious aging of the immune system in down syndrome: alteration of B lymphocytes, T-lymphocyte subsets, and cells with natural killer markers. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1990;7:213–8.

Ugazio AG, Maccario R, Notarangelo LD, Burgio GR. Immunology of down syndrome: a review. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1990;7:204–12.

Sullivan KD, Evans D, Pandey A, Hraha TH, Smith KP, Markham N, et al. Trisomy 21 causes changes in the circulating proteome indicative of chronic autoinflammation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14818. Proteomics approach showing that individuals with DS have high circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL6, MCP-1, IL22, TNFalpha).

Araya P, Waugh KA, Sullivan KD, Núñez NG, Roselli E, Smith KP, et al. Trisomy 21 dysregulates T cell lineages toward an autoimmunity-prone state associated with interferon hyperactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(48):24231–41. Important study of T cells in individuals with DS providing evidence for elevated levels of basal IFN signalling and interferon hyperreactivity that may contribute to increased autoimmunity in DS.

Waugh KA, Araya P, Pandey A, Jordan KR, Smith KP, Granrath RE, et al. Mass cytometry reveals global immune remodeling with multi-lineage hypersensitivity to type i interferon in down syndrome. Cell Rep. 2019;29(7):1893–908.e4. Mass cytometry approaches were used to reveal a proinflammatory state with widespread hypersensitivity to INN alpha in individuals with Down syndrome.

Ferreira RC, Guo H, Coulson RMR, Smyth DJ, Pekalski ML, Burren OS, et al. A type I interferon transcriptional signature precedes autoimmunity in children genetically at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(7):2538–50.

Lombardi A, Tsomos E, Hammerstad SS, Tomer Y. Interferon alpha: the key trigger of type 1 diabetes. J Autoimmun. 2018;94:7–15.

Morris JK, Cole TJ, Springett AL, Dennis J. Down syndrome birth weight in England and Wales: implications for clinical practice. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167(12):3070–5.

Goldacre RR. Associations between birthweight, gestational age at birth and subsequent type 1 diabetes in children under 12: a retrospective cohort study in England, 1998–2012. Diabetologia. 2018;61(3):616–25.

Lönnrot M, Lynch KF, Elding Larsson H, Lernmark Å, Rewers MJ, Törn C, et al. Respiratory infections are temporally associated with initiation of type 1 diabetes autoimmunity: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia. 2017;60(10):1931–40.

Snell-Bergeon JK, Smith J, Dong F, Baron AE, Barriga K, Norris JM, et al. Early childhood infections and the risk of islet autoimmunity: the diabetes autoimmunity study in the young (DAISY). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2553–8.

Tapia G, Størdal K, Mårild K, Kahrs CR, Skrivarhaug T, Njølstad PR, et al. Antibiotics, acetaminophen and infections during prenatal and early life in relation to type 1 diabetes. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(5):1538–48.

Grut V, Söderström L, Naumburg E. National cohort study showed that infants with Down's syndrome faced a high risk of hospitalisation for the respiratory syncytial virus. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(9):1519–24.

Uppal H, Chandran S, Potluri R. Risk factors for mortality in down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2015;59(9):873–81.

Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, Hutchinson DS, Smith DP, Wong MC, et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature. 2018;562(7728):583–8.

Vatanen T, Franzosa EA, Schwager R, Tripathi S, Arthur TD, Vehik K, et al. The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1 diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature. 2018;562(7728):589–94.

Harbison JE, Roth-Schulze AJ, Giles LC, Tran CD, Ngui KM, Penno MA, et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability in children with islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20(5):574–83.

Biagi E, Candela M, Centanni M, Consolandi C, Rampelli S, Turroni S et al. Gut microbiome in down syndrome. 2014;9(11):e112023.

Lyle R, Béna F, Gagos S, Gehrig C, Lopez G, Schinzel A, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in down syndrome identified by array CGH in 30 cases of partial trisomy and partial monosomy chromosome 21. Eur J Hum Genet : EJHG. 2009;17(4):454–66.

Li C-M, Guo M, Salas M, Schupf N, Silverman W, Zigman WB, et al. Cell type-specific over-expression of chromosome 21 genes in fibroblasts and fetal hearts with trisomy 21. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:24.

Prandini P, Deutsch S, Lyle R, Gagnebin M, Delucinge Vivier C, Delorenzi M, et al. Natural gene-expression variation in down syndrome modulates the outcome of gene-dosage imbalance. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(2):252–63.

Kozhakhmetova A, Wyatt RC, Caygill C, Williams C, Long AE, Chandler K, et al. A quarter of patients with type 1 diabetes have co-existing non-islet autoimmunity: the findings of a UK population-based family study. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;192(3):251–8.

Concannon P, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Todd JA, Smyth DJ, Pociot F, Bergholdt R, et al. A human type 1 diabetes susceptibility locus maps to chromosome 21q22.3. Diabetes. 2008;57(10):2858–61.

Grant SFA, Qu HQ, Bradfield JP, Marchand L, Kim CE, Glessner JT et al. Follow-up analysis of genome-wide association data identifies novel loci for type 1 diabetes. 2009;58(1):290–295.

Zhernakova A, Stahl EA, Trynka G, Raychaudhuri S, Festen EA, Franke L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis identifies fourteen non-HLA shared loci. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(2):e1002004.

Wattenhofer M, Shibuya K, Kudoh J, Lyle R, Michaud J, Rossier C, et al. Isolation and characterization of the UBASH3A gene on 21q22.3 encoding a potential nuclear protein with a novel combination of domains. Hum Genet. 2001;108(2):140–7.

Ge Y, Concannon P. Molecular-genetic characterization of common, noncoding UBASH3A variants associated with type 1 diabetes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26(7):1060–4.

Skogberg G, Lundberg V, Lindgren S, Gudmundsdottir J, Sandström K, Kämpe O, et al. Altered expression of autoimmune regulator in infant down syndrome thymus, a possible contributor to an autoimmune phenotype. J Immunol. 2014;193(5):2187–95.

Lima FA, Moreira-Filho CA, Ramos PL, Brentani H, Lima LdA, Arrais M et al. Decreased AIRE expression and global thymic hypofunction in down syndrome. 2011;187(6):3422–3430.

Giménez-Barcons M, Casteràs A, Armengol MdP, Porta E, Correa PA, Marín A et al. Autoimmune predisposition in down syndrome may result from a partial central tolerance failure due to insufficient intrathymic expression of AIRE and peripheral antigens. 2014;193(8):3872–3879.

De Weerd NA, Nguyen T. The interferons and their receptors-distribution and regulation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90(5):483–91.

Khor B, Gagnon JD, Goel G, Roche MI, Conway KL, Tran K, et al. The kinase DYRK1A reciprocally regulates the differentiation of Th17 and regulatory T cells. eLife. 2015;4. This key publication links DYRK1A to the function of the immune system.

Williams GM, Neville P, Gillespie KM, Leary SD, Hamilton-Shield JP, Searle AJ. What factors influence recruitment to a birth cohort of infants with Down's syndrome? Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(8):763–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all collaborators involved in the studies of DS and all the participants who have contributed to their studies.

Funding

The authors received grant support from the Jerome Lejeune Foundation and the Diabetes Research and Wellness Foundation for studies of diabetes in children with DS. GM is funded by a University of Bristol PhD scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Other Forms of Diabetes and Its Complications

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mortimer, G.L., Gillespie, K.M. Early Onset of Autoimmune Diabetes in Children with Down Syndrome—Two Separate Aetiologies or an Immune System Pre-Programmed for Autoimmunity?. Curr Diab Rep 20, 47 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-020-01318-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-020-01318-8