Abstract

Curriculum resources such as textbooks and lesson guides communicate messages about the social relations between the teacher, students, artefacts, and the mathematics. Because of their implicit nature, these messages can be hard to surface and perhaps therefore are not frequently covered in curriculum resource analysis. Tackling this shortcoming, we examine mathematics lesson guides or the daily lesson descriptions written for elementary teachers. Drawing on multimodality and activity theory, we characterize the social relations messaged in the lesson guides in terms of two constructs: authority and distance. We present and illustrate an analytical approach to uncovering these messages in lesson guides from Sweden, USA, and Flanders. Our analytical approach enabled us to distinguish configurations of social relations that vary primarily across the three educational contexts, which strengthens our argument for viewing the configuration of social relations as a cultural script.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A duality intrinsic to mathematics curriculum resources is that they are written to guide the teaching of mathematics to others, but, at the same time, they cannot replace the actual teaching (Love & Pimm, 1996; Otte, 1983). In dealing with this dualism, curriculum resource designers deploy various mechanisms to influence the enacted curriculum. We use the term curriculum resource to refer to a genre of artefacts designed to support a program of instruction (Pepin et al., 2017; Remillard, 2012). The term curriculum refers to sequencing or mapping learning over time; resources signal their role as tools for teachers. In addition to sequencing and organizing the mathematics content in particular ways, curriculum resources also seek to configure the relations between teacher, students, artefacts, and mathematics. These social relations are at the heart of classroom instruction (Love & Pimm, 1996; Pepin & Haggarty, 2001; Rezat & Sträßer, 2012). While official curricula typically do not contain many details about these relations (Boesen et al., 2014; Valverde et al., 2002), curriculum resources such as textbooks and lesson guides do.

The configuration of social relations has received relatively little attention in mathematics curriculum resource analysis (Fan et al., 2013; Herbel-Eisenmann, 2007; Morgan, 1996; Remillard & Kim, 2020). We assume that this imbalance is related to the often implicit nature of these messages (Herbel-Eisenmann, 2007; Love & Pimm, 1996). This paper addresses this imbalance through an analysis of printed lesson guides from Sweden, the USA, and Flanders (Belgium). Student textbooks are often complemented with a teacher’s guide, written for teachers. Such guides are generally comprised of multiple components, including lesson guides, assessments, supplemental resources, and sometimes descriptions of the authors’ vision behind the structuring of mathematical content. It is in the lesson guides that authors explicitly communicate with teachers about the intended daily lessons and, in so doing, signal messages about the envisioned social relations at the heart of classroom instruction.

Our interest in social relations communicated in lessons guides emerged from an analysis of how these guides from Sweden, the USA, and Flanders communicate to teachers and what they communicate about. Initially focusing on the written communication, we observed that lesson guides also communicate through non-written modes, such as the layout of the page and the images used. Together, it appeared that these modes played a role in structuring interactions and configuring the relations between teacher, students, artefacts, and mathematics. Unraveling how these three modes communicate messages about social relations was not a straightforward process, as it required us to step from overt to more tacit messages.

Our aim is to present an analytical approach for analyzing how lesson guides communicate about the social relations between teacher, students, artefacts, and mathematics. In order to move from overt to tacit messages, we combined multiple theoretical and analytical lenses. We describe these lenses in Sects. 2–4. We theorize the configuration of social relations in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we argue for understanding the configured social relations as a cultural script and draw on activity theory to study the underlying motives. In Sect. 4, we frame lesson guides as multimodal artefacts and describe key features of a multimodal lens. After describing the analyzed lesson guides in Sect. 5, we draw on the theoretical tools developed in the previous sections to lay out and illustrate our analytical approach in Sects. 6 and 7.

We believe that studying the multimodal nature of lesson guides across contexts has the potential to expose these resources as cultural artefacts. Thus, in line with the focus of this special issue, and understanding language broadly, we examine the language of curriculum resources. Specifically, we attempt to uncover how multimodal resources are used to communicate to teachers about intended mathematics teaching and learning, and in so doing invoke cultural meanings at play.

2 The configuration of social relations in mathematics lesson guides

We use configuration of social relations to refer to how the teacher and students are positioned in relation to one another, to central artefacts, such as the textbook and chalkboard, and mathematics itself. In specifying these relations, we employ Rezat and Sträßer’s (2012) didactical tetrahedron shown in Fig. 1. As the top of the tetrahedron, Rezat and Sträßer added mediating artefacts to the standard components of the didactical triangle, showing the teacher, students, mathematics, and artefacts as “interlaced beyond the possibility of separation” (p. 645). They also argue, relating to activity theory, that “social and institutional aspects of teaching and learning should be taken into account” (p. 642), which they have done by including an additional layer of nodes, such as conventions and norms about being a student or a teacher. Our analytical focus is the segments between the teacher, students, artefacts, and mathematics, which according to Rezat and Sträßer, indicate relations, but do not offer characteristics of these relations (p. 649). We aim to uncover some of the implicit characteristics of these relations.

Rezat and Sträßer’s (2012) tetrahedron model of the didactical situation

According to Halliday (1978), specifying the interpersonal and social relations between the author and others is one of the metafunctions of texts. Halliday and others (e.g., Herbel-Eisenmann, 2007; Morgan, 1996) have examined how authors perform this function through linguistic choices, which affect the meanings constructed by users. Our analysis builds on this work by exploring how multimodal choices made by curriculum developers express social relations.

We identified two primary ways that the multimodal communication in lessons guides configures relations in mathematics teaching and learning: by specifying authority within these relations and by positioning the nodes in terms of closeness or distance. Our use of the concept of authority relates to Amit and Fried’s (2005) analysis of classroom interactions. Examining authority in mathematics classrooms, they argue, takes into account the source and ownership of knowledge and expertise, how correctness is determined, and how the outcomes of learning are shaped. While traditionally, teachers hold ultimate authority for mathematics knowledge in classrooms, many argue that this authority should be given to the logic and content of the discipline of mathematics (Amit & Fried, 2005). Others argue for sharing authority for mathematics knowledge with students or locating it within the classroom community. Our consideration of authority in lesson guides takes into account where mathematical authority and decision making rest and the potential role of central artefacts, such as the textbook and the chalkboard in constraining or supporting the exercise of authority.

We also consider the relative distance in the positioning of teachers and students in relation to one another, the mathematics, and central artefacts in the lesson. While all nodes are fundamental constituents of the didactical tetrahedron, in different instructional arrangements, two (or more) constituents might be brought into closer relation to one another, while others are more peripheral to the interaction. We use relative distance to conceptualize which constituents of the tetrahedron are positioned as most active or central in teaching and learning practices in lesson guides and which are more distant. To our knowledge, this concept has not been previously explored in the mathematics curriculum resource literature. Through our analysis, we aim to further conceptualize this dimension.

3 Configured social relations as cultural scripts

Messages about social relations in textbooks can be both subtle and persistent, as suggested in the work of Herbel-Eisenmann and Wagner (Herbel-Eisenmann, 2007; Herbel-Eisenmann & Wagner, 2007). This research has focused primarily on how linguistic features in students’ mathematics textbooks and actual classroom discourse communicate messages about the positioning of the students, teacher, textbook, and mathematical content. Their study of pronouns, imperatives, and modality in texts within a 64-page reform-oriented unit on modeling for middle school revealed specific messages about social relations in mathematics teaching. For instance, students were often positioned as “scribblers” and the textbook was positioned as the mathematical authority. These kinds of messages were in conflict with the ideology behind the intended reform and thus point to the covert and complex nature of messages of social relations in textbooks.

We propose to understand the configuration of the social relations between the teacher, students, artefacts and mathematical content in lesson guides as a cultural script. Stigler and Hiebert (1999) describe teaching as a cultural activity represented in cultural scripts. Cultural scripts, or mental pictures of what teaching is, “guide behavior and also tell participants what to expect. Within a culture, these scripts are widely shared, and therefore they are hard to see.” (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999, p. 85). The configuration of social relations in lesson guides is one such cultural script that guides the teachers’ behavior and tells them what to expect from the other nodes in the didactical tetrahedron. The abovementioned study of Herbel-Eisenmann and Wagner has shown how widely shared and hard to see these cultural scripts are. Even when purposefully designing curriculum resources to change teaching, the pervasive nature of the configuration of social relations resulted in texts that conflicted with the ideology of the intended reform.

Cultural scripts—and thus the configuration of social relations—rest on a small set of tacit core beliefs about how students learn and about the teacher’s related role (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999). Thus, understanding the cultural nature of teaching mathematics requires one to map out not only the cultural scripts, but also to consider the underlying set of core beliefs. To understand the origins of the configured social relations, we need to dig deep. Activity theory, which also grounds Rezat and Sträßer’s (2012) tetrahedron model of the didactical situation, has helped us to consider some of the subtleness of social relations in lesson guides.

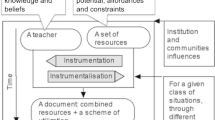

From an activity-theoretical perspective, teaching mathematics can be understood as an activity with a strong mediational functioning. Figure 2 shows the more easily discernible mediators located at the tip, including the nodes of Rezat and Sträßer’s (2012) didactical tetrahedron: the chalkboard, textbook, and lesson guide (instruments) mediate interactions between the teacher (subject) and school mathematics and students (objects). The deep social structure, however, is located underneath the surface—often hidden from scrutiny. Indeed, rules, the community, and division of labor mediate activities in a fundamental and often tacit way (Engeström, 1998). Thus, to understand the motives of the mediations in the tip, one needs to consider the underlying rules, community, and division of labor. It is this “motivational sphere of classroom culture” (Engeström, 1998, p.76) or the “relatively small and tacit set of core beliefs” (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999, p. 87) that ground classroom teaching.

Engeström's (1998) model of the activity system

Engeström’s (1998) activity-theoretical analysis of the planning work of a group of elementary school teachers describes how adjusting the rules and division of labor enabled a significant change in practice. Shifting rules concerning the time schedule and breaking down the boundaries between lesson subjects, along with the division of labor by grouping students in alternative ways, eventually allowed the teachers to work toward an integrated curriculum, which represented a significant change compared to their previous teaching practices. This study illustrates that an analytical focus on this motivational sphere in terms of rules, division of labor, and community can help to uncover some of the very influential but also hidden curriculum. We understand the lesson guides’ subtle messages about the social relations, communicated through their multimodal design, to be motivated by these “relatively inconspicuous, recurrent, and taken-for-granted aspects of school life” (Engeström, 1998, p. 76).

4 Lesson guides are multimodal artefacts

Understanding lesson guides as multimodal artefacts represents a departure from the longstanding tradition that spoken and written language are the main resources for designing and realizing learning environments (Bezemer & Kress, 2015; Jewitt, 2009). In reality, designers of contemporary curriculum resources, like lesson guides, use “an ensemble of semiotic features” or modes (e.g., writing, images, layout) “that provides the ground for learning and in that way may shape what learning is and how it may take place” (Bezemer & Kress, 2008, p. 168). Modes are socially and culturally shaped resources for meaning making; “Image, writing, layout, speech, moving image are examples of modes, all used in learning resources” (Bezemer & Kress, 2008, p. 171). These modes have different modal resources, which are deployed through organizational and structuring decisions made by the designers (Bezemer & Kress, 2015; Jewitt, 2009). Written communication, for example, has graphical resources, like font style and size, lexical resources, like content and tone, that shape the style of communication, and grammatical resources, like tense and use of pronouns, that communicate the relationship between writer, reader, and message. Images can vary in size, style, color, shape, and content. Layout involves the arrangement of these resources on the page. In this way, modes and their modal resources are not discrete, but intersect and work together in multimodal artefacts. Images represent a prominent mode in lesson guides, yet the size and placement of images can also be seen as modal resources in the mode of layout.

As we describe in Sect. 6, we combine multimodal lenses with tools from activity theory to examine what is communicated about the social relations in mathematics lesson guides prepared for use by teachers in three educational contexts. We first describe the lesson guides.

5 Description of analyzed lesson guides

We examined 72 lesson guides from six textbook series from Sweden, the USA, and Flanders, the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, which has its own educational system. We selected these contexts to leverage first-hand experience of the authors, however, they also share commonalities, such as official mathematics curricula that value conceptual understanding, problem solving, reasoning, communication and active involvement of students (Boesen et al., 2014; NCTM, 2000; Verschaffel, 2004). Still, the three contexts have substantially different cultural traditions and school systems (Van Steenbrugge et al., 2019). In line with Clarke (2006), we believe comparative analysis allows us to view teaching practices in any one context as located within culturally determined norms and expectations.

We selected two frequently used textbook series per context, indicative of the range of available options, published in print form. Table 1 lists the six textbook series included in the study. All six textbooks were published by commercial publishers and were accompanied by a teacher’s guide that includes lesson guides or descriptions for daily lessons. The two series from the USA, Everyday Mathematics (EM) and Math in Focus (MiF), represent two different instructional influences at play when we initiated this study. EM was one of the Standards-based textbooks developed by university-based mathematics educators. MiF was adapted from one of the primary textbooks developed and used in Singapore and was more directive in approach. Both Flemish textbook series, Kompas (KP) and Nieuwe Tal-rijk (NT) were authored by a group of publisher employees, teachers, teacher educators, and members from the inspectorates. They reflect typical textbook series in Flanders in that they were both quite directive and detailed. The Swedish textbook series represent two distinct approaches, reflective for the mathematics textbook landscape in Sweden. Matte Direkt (MD) had been revised and adapted from earlier versions of the same text to meet the new national curriculum. MD was more traditional in that it provided short descriptions in the lesson guides. Matte Eldorado (ME), on the other hand, was more innovative, including the provision of some more teacher support in the lesson guides and was designed by teacher educators to follow the new national curriculum.

We analyzed a sample of 72 lesson guides, 12 from each of the six textbook series, randomly drawn from the strands on (a) numbers and operations, and (b) fractions, and evenly distributed among grades 3, 4, and 5. These two strands represent major mathematical contents in these grades. Figures 4 and 5 respectively represent an example page of the lesson guides for Kompas and Matte Eldorado. Example pages of the lesson guides for the other four textbook series can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

Analysis of layout and image took place on the original lesson guides collaboratively by both authors. Because the common languageFootnote 1 between both authors is English, the Swedish and Flanders lesson guides were at times complemented with the English translations also used for the analysis of the written communication (Remillard et al., 2014; Van Steenbrugge & Bergqvist, 2014). In these English translations, the original layout and images were maintained. We detail our analytical approach in the following section.

6 Analytical approach

Our analysis proceeded in three stages, each building on the previous and allowing us to surface more tacit and subtle messages, moving from “the tip of the iceberg” to “the deep social structure” or “the hidden curriculum” (Engeström, 1998). These stages are synthesized in Fig. 3, along with the key dimensions used in each. Before detailing each stage of analysis in Sect. 7, we provide a brief overview of the key dimensions and an illustrative example from two lesson guides.

Stage 1, represented in the box on the left, involved examining the lesson guides, using a multimodal lens (Bezemer & Kress, 2015). The analysis focused on three modes of communication that permeate mathematics lesson guides: written communication, layout, and image. Our analysis of written communication built on previously undertaken analyses of printed teacher’s guides (Remillard et al., 2014; Van Steenbrugge & Bergqvist, 2014). For this written analysis, we considered two primary modal resources: (a) extent or quantity of writing, and (b) the approach to communicating through writing with the teacher.

Layout refers to how the various components are placed in relation to one another on the page. Our analysis of the layout of the lesson guides considered what was placed where and how visual markers, such as headings, colors, and numbers provided information about the nature of the contents, its place in the lesson, and how teachers might be expected to navigate the ensemble of material provided. Other visual markers that are components of the layout include boxes or margins, which are often used to set particular content apart from the more central information, identifying it as either highly important or relegating it to the margins of the page.

Images are used throughout lesson guides from all three contexts as a mode of communication. Our analysis of this mode considered the content of the images—what is being pictured, as well as the size and location of the images. Here, it is evident that the modes and modal resources overlap, and some modes (such as image) might serve as a modal resource for another mode (such as layout).

Stage 2, represented by the middle box, involved using findings from the first stage to infer ways that the lesson guides structured teaching and learning interactions. When looking comparatively across the guides, three primary mechanisms for structuring interactions surfaced: (a) teachers’ reading path through the guides; (b) the intended locus of instruction; and (c) the voice of the text. Moving from our findings in Stage 1 to infer characteristics associated with the structuring mechanisms in Stage 2 involved integrating our analysis of all three modes.

Teacher’s reading path refers to how the teacher’s reading of the guide is ordered. According to Bezemer and Kress (2015) and Love and Pimm (1996), the spatial ordering of modal resources in textbooks creates an implicit ordering or “pathways,” by which learners are “expected to engage with the selected elements,” or, on the other hand, “leave the ordering as much as possible to the user” (Bezemer & Kress, 2015, p. 78). Through an analysis of layout in lesson guides, assisted by the modes of written communication and image, we were able to characterize how the reading path was structured and the level of teacher agency over the path.

Locus of instruction refers to what is signaled as the central focus of interactions during the lesson. In some guides, a chalkboard might be indicated as focal, while the student textbook or student–teacher interactions might be positioned as focal in other guides. We used our analysis of images in the guides, assisted by written communication and visual markers associated with layout, to examine messages about the locus of instruction.

Voice of the text extends the mode of written communication, described earlier, but is inclusive of all modes of communication. To characterize the voice of the text, we coordinated the lesson guides’ approach to written communication with the analysis of the reading path and locus of instruction, to arrive at a holistic characterization of the voice of the text. In this way, the voice of the text captures all three structuring dimensions, communicating in both writing and visual modes.

Stage 3, represented by the box to the right in Fig. 3, focuses on features of the social relations, inferred from the structuring of interactions. Drawing on an activity-theoretical lens (Engeström, 1998), we applied the concepts of rules and division of labor to infer authority and distance as features of social relations communicated through the lesson guides’ multimodal ensemble. As discussed previously, our consideration of authority in lesson guides takes into account where mathematical authority and decision making reside (Amit & Fried, 2005) and the potential role of central artefacts, such as the textbook and the chalkboard in constraining or supporting the exercise of authority. We use distance to refer to the positioning of participants in the didactical tetrahedron (teacher, student, artefacts, and mathematics) in relative proximity to one another during intended lessons. Nodes that are closest together are most active in accessing the mathematics.

Figures 4 and 5 include examples (with English translation) of a single page from a lesson guide of Kompas (Flanders) and Matte Eldorado (Sweden), both for grade 3, along with a synthesis of all three stages of our analytical approach. These two examples, together, illustrate the stark differences we found across lesson guides. For additional examples of pages from lesson guides from the other four textbook series and related analyses, see the electronic supplementary material.

7 Employing the analytical approach to analyze lesson guides

In the following sections, we describe and illustrate how we used the analytical approach, summarized in the previous section, to uncover the configuration of social relations in mathematics lesson guides from Sweden, the USA, and Flanders. The description of each stage can be related to the sample pages of the lesson guides and related analysis in Fig. 4 for Kompas, Fig. 5 for Matte Eldorado, and in the electronic supplementary material for Nieuwe Tal-rijk, Everyday Mathematics, Math in Focus, and Matte Direkt.

7.1 Stage 1: Analyzing modes of communication and modal resources

The analysis of the written text had been undertaken previously (Remillard et al., 2014; Van Steenbrugge & Bergqvist, 2014) and was incorporated into this study. This analysis used a coding scheme developed by the ICUBiT (Improving Curriculum Use for Better Teaching) research project that categorized each sentence or complete phrase (referred to as a unit) according to its focus and approach to communication (Remillard & Kim, 2020). The approach to communication codes labeled statements as directive, educative, or a combination of both (hybrid). Purely directive statements simply directed teacher actions without providing underlying rationale or explanation. Purely educative statements communicated to the teacher about underlying rationales or design principles, student thinking or strategies, or mathematical ideas. Hybrid statements directed teacher action, while providing explanatory information. Counts of units and percentages of each code were calculated for each lesson. The per-lesson means of these values for each series are shown in Table 2.

The approach used to analyze layout and image was developed emergently through a side-by-side comparison of the lesson guides, jointly undertaken by both authors. Through this process, we identified the modal resources for each mode that were the most visually prominent and varied across lesson guides. For layout, we identified visual markers, such as headings, font design, numbering, and the use of boxes, and location, including placement in main flow of the page versus the margin. For image, we identified the content, size, and location of images on the page. Throughout the 12 analyzed lesson guides per textbook series, we found high internal consistency in the selection of modal resources, how they were arranged in the lesson guides, and how they were used to communicate to teachers. The analysis for image and layout is summarized in Table 3.

The KP (Flanders) lesson guides included three to six pages of written information for the teacher, which was primarily directive in nature. The focus was on what to teach and how to teach it with little attention given to teaching decisions. Lesson guides contained colored and numbered headings, noting the phase of the lesson and signaling the sequence the teacher should follow. Necessary materials were listed in the margin. The most prominent images were chalkboards, generally large, placed at the center of the page and detailing what the teacher should write on the board (see Fig. 4).

The NT (Flanders) lesson guides, typically three to five pages of length, contained written communication that was primarily directive in nature, with a focus on what to teach and how to teach and little attention given to teaching decisions. Lesson guides contained numbered and bolded headings that signal the lesson structure and sequence to read through the lesson guide. Images of the content to be written on the chalkboard were placed centrally on the page and surrounded by related written teacher directions.

The EM (USA) lesson guides included four to six pages of written communication, which included a combination of directive and educative messages. The focus of communication included mathematics, student thinking, and guidance related to facilitating classroom interactions. Lesson guides used colored and numbered headings to provide a clear, sequenced pathway through the components of the lesson but also announced options for modifying the lesson suggestions. Small images of corresponding pages in the student textbook were shown in the margin, where they shared space with other notes to the teacher about mathematics concepts, common student misconceptions, and what to look for in student responses.

MiF (USA) lesson guides included four to six pages of written communication including teacher directives containing mathematical detail and descriptions of mathematical ideas, student thinking, and authors’ design decisions. Colored headings provided a clear sequenced pathway through the lesson components. Teacher notes in boxes and under headings included options for modifying lesson activities. Images of student textbook pages typically spanned the upper half of lesson guide pages.

MD (Sweden) lesson guides typically consisted of one page; the written communication included descriptions of the tasks that the students were to work on, some references to intended student understanding or aim of the task, and very little directions for teaching. A clear visual pathway of the lesson was not specified, except for a bolded heading and box that foregrounded the lesson introduction. Images of student textbook pages, placed on the left or right side of the written descriptions occupied half of a page.

The ME (Sweden) lesson guides were typically one to two pages long; the written communication described the tasks students were to work on and made some references to intended student understanding or the aim of the task but provided very few directions for teaching. A clear visual pathway of the lesson was not specified. Instead, colored headings signaled ways to modify tasks as needed. Sometimes a box at the beginning of the lesson foregrounded the lesson goal. Images of student textbook pages occupied the upper half of the page (see Fig. 5).

7.2 Stage 2: using multimodal analysis to infer the structuring of interactions

Stage 2 of our analysis considered how patterns surfaced in our multimodal analysis served to structure teachers’ interactions with the lesson guides, moving from the left box to the middle box in Fig. 3. Table 4 synthesizes how we drew on multimodality to facilitate this move, illustrating how the modes of layout, image, and written communication in the lesson guides communicate particular messages about (a) teachers’ reading paths, (b) the locus of instruction, and (c) the voice.

7.2.1 Teachers’ reading path

Our analysis of the structure of a reading path considered the use of the layout’s modal resources to signal how strictly a pre-established sequence of reading was intended. Frequent use of bolded and/or numbered headings and the backgrounding of marginal notes generally suggested a structured, singular reading path (as in KP and NT from Flanders). A lack of, or infrequent use of these modal resources (as in MD and ME from Sweden) marked an unstructured reading path, which we understood as an indicator that the teacher had agency over the reading path (hence the empty third quadrant). The teachers are expected to work their own way through the text with minimal structuring support from the lesson guide. Even in the presence of a structured path, we found differences in how much agency teachers were given over the reading process. EM and MiF (USA) used numbered and bolded headings to signal a structured reading path regarding the lesson, but the arrangement and foregrounding of related items in the margin on each page, including mathematics explanations and suggestions for modifying the lesson, offered an assemblage of related information. With this layout and written communication, teachers were afforded agency over their reading path through the lesson guide. In contrast, the singular pathway offered in KP and NT downplayed teachers’ agency over their reading path.

7.2.2 Locus of instruction

We used our analysis of images in the lesson guides, assisted by written communication and visual markers associated with layout, to examine messages about the locus of instruction. Frequent, and often large, placement of images of chalkboards central on the lesson guide page, showing the content to be presented on the board (as in KP and NT from Flanders), placed the classroom chalkboard at the center of the lesson. In contrast, large images of the student textbook pages, arranged centrally on the page (as in MD and ME from Sweden and MiF from USA), foregrounded the student text as the locus of instruction. In EM (USA), the locus of instruction cannot be detected from the images alone. Images of the student textbook pages are present, but backgrounded by their placement in the margin. Examining additionally the layout in conjunction with the written communication reveals that the locus of instruction is student–teacher interaction. The written communication includes considerable decision-making support for setting up teacher-student and student–student conversations, such as how to assess student progress and options to modify activities, often placed in a box and/or the margin.

7.2.3 Voice of the text

As stated earlier, we coordinated our analysis of written communication with that of the reading path and locus of instruction to get a holistic picture of the voice of the text, characterizing it as either directive, instructive, or descriptive. These characteristics are summarized in Table 4.

We characterized KP and NT (Flanders) as directive in their communication. Through written communication, images, and layout, the KP and NT guides directed teacher actions, such as what to say and what to write on the board, focusing on these actions almost exclusively. The teacher is given little room for decision making. We characterized EM and MiF (USA) as instructive, because the guides used written communication to both direct teacher actions and explain ideas behind these actions. Additionally, teacher notes in boxes placed alongside the more directive text focused on how to interpret and respond to students during classroom interactions, providing support for teacher decision making. We characterized ME and MD (Sweden) as descriptive. They offered minimal directive language, but included relatively large pictures of student textbook pages and described the tasks students were to complete, periodically making reference to intended student understanding. This communication leaves the teacher to decide herself/himself how to teach.

Putting these findings together, makes visible that each lesson guide assumed and was reproducing a particular vision of mathematics teaching and learning in terms of the envisioned social relations. In the following section, we use authority and distance to characterize how lesson guides configure these relations differently.

7.3 Stage 3: from structuring of interactions to inferring features of social relations

Table 5 captures how we drew on activity theory to infer features of social relations from the structuring of interactions—the move from the middle box to the one on the right in our analytical approach (Fig. 3). Specifically, we applied the concepts of rules and division of labor as analytical tools to help us infer authority and distance as features of social relations. The move from Stage 2 to 3 consists of three major components that respectively focus on (a) the rules as to who has authority over whom, (b) the division of labor in accessing the mathematics, and (c) visualizing the features of authority and distance.

7.3.1 Rules as to who has authority over whom

Lesson guides communicate explicitly with teachers and in so doing, they inscribe rules about authority not only during classroom teaching but also during lesson planning. Hence, we differentiated between the rules of authority during lesson planning and during lesson enactment. The top of Table 5 lists the rules we inferred from the voice, reading path, and locus of instruction as to who has authority over whom during lesson planning; the bottom lists the rules of authority and division of labor during the envisioned classroom enactment.

7.3.1.1 Lesson planning rules

Considering authority rules during lesson planning, we identified instances where (a) the lesson guide had authority over the teacher, (b) the lesson guide and teacher shared authority, and (c) the teacher had authority over the lesson guide.

Lesson guide has authority over teacher. We understood a directive voice, by means of written directives and a structured reading path that downplayed teacher agency over it, as an indicator that the lesson guide had authority over the teacher. This was the case for KP and NT (Flanders), where written, directive guidelines specified how to teach the content on the chalkboard, leaving little room for teacher decision making. We understood KP and NT’s structured reading path, consisting of numbered headings and subheadings, and written directives in boxes and margins as downplaying teacher agency over the reading path as an additional means by which the lesson guides were given authority over the teacher.

Lesson guide and teacher share authority. An instructive voice, with written guidelines supporting teacher decision making, including a structured reading path that stressed teacher agency over it, was an indicator that the lesson guide granted some authority to the teacher. Both EM and MiF (USA) communicated in an instructive voice and directed teachers in what to do, but also included decision-making support, such as possible ways to modify activities, based on, for instance, an assessment of student understanding. Further, their reading paths provided structure for how to read through the lesson guide, but also included optional information in boxes and the margin and, in doing so, provided multiple entry points for the teacher to the reading path, giving them agency over it. Teachers can read these supports as they wish or think it is applicable to their group of students, which we understood as a sharing of authority with the teacher.

Teacher has authority over lesson guide. A descriptive voice, including written descriptions of the tasks in the student textbooks and an unstructured reading path, was an indicator that the teacher had authority over the lesson guide. We observed this relation in MD and ME (Sweden), where written guidelines communicated what the exercises in the textbook were about, but usually did not direct the teacher on how to teach the lesson. We understood such instances in combination with unstructured reading paths in MD and ME, as instances where authority was given to the teacher.

7.3.1.2 Lesson enactment rules

For our analysis of the rules during lesson enactment, we focused on how authority was distributed between the teacher, students, central artefacts, and mathematics. Our analysis revealed instances where (a) the teacher had authority over the students using the chalkboard or textbook, (b) authority was shared between the teacher and students, and (c) authority was shared between the students and their textbook (Table 5).

Teacher has authority over students. We interpreted a directive or instructive voice in combination with the chalkboard or textbook as locus of instruction as indicators of teacher authority over the students. This was the case for KP and NT (Flanders) and MiF (USA), where written directives, a structured reading path, and images of the chalkboard or textbook specified how to guide the students through the content on the chalkboard or in the textbook.

Teacher and students share authority. We saw an instructive voice and the backgrounding of the textbook as locus of instruction as indicators that the teacher was expected to share authority with students, which we observed for EM (USA). Written guidelines supported the teachers to facilitate classroom interaction and images of the textbook were small and placed in the margin, backgrounding these artefacts as the locus of instruction. Rather than having authority over the students as we observed for KP and NT (Flanders) and MiF (USA), we understood these intended classroom discussions as instances where the teacher shared mathematical authority with the students.

Students and textbook share authority. We took a combination of the textbook as locus of instruction and a descriptive voice describing the exercises in the textbook, but not how to proceed through the textbook, as indicators that the students shared authority with their textbook. We observed this configuration in MD and ME (Sweden), where textbooks provided the students and teacher with exercises but limited directions on how to engage with their textbook. We understood such instances, together with teacher notes describing how to observe students’ progress in the textbooks, as indications that the students and textbook shared authority. We understood the teacher’s facilitating role of the student—textbook interaction as one that had limited authority over the student or textbook.

7.3.2 Division of labor in the mathematics classroom

Analysis of the rules of authority helped us to identify patterns as to who is most active in accessing the mathematics, which we understood as an aspect of how the labor during the teaching of mathematics was divided. As indicated in Table 5, we noted instances where (a) the teacher and chalkboard were active, (b) the teacher and textbook were active, (c) both teacher and students were active, and (d) the students and textbook were active.

We saw the teacher having authority over the students through the chalkboard as an indicator that the teacher and chalkboard should be active in connecting the students to the mathematics, which we observed in KP and NT (Flanders). We saw the teacher having authority over the students through the textbook as an indicator that the teacher and textbook should be actively connecting the students to the mathematics, as observed in MiF (USA). A teacher and students sharing authority was an indicator that the teacher and students should together establish the connection to mathematics, as we observed in EM (USA). Students sharing authority with their textbook was an indicator that the students worked actively with their textbook to access mathematics, a pattern we found in ME and MD (Sweden).

7.3.3 Visualizing authority and distance

We used Rezat and Sträßer’s (2012) didactical tetrahedron as the base model for the drawing of social relations but further specified the relations in terms of authority and distance. We used arrows to indicate who had authority over whom (→), whether two nodes shared authority (↔), or whether no authority was indicated (—), as inferred from the rules of authority analysis. We used distance to indicate the nodes that were particularly active in accessing the mathematics, inferred from the division of labor analysis. Relatively shorter distances between nodes indicate those that were most active in connecting the students to mathematics.

Figure 6 shows the visualizations of authority and distance in the didactical tetrahedron for the analyzed lesson guides. In KP and NT (Flanders), the green arrow is indicative for the lesson guide’s authority over the teacher during lesson planning. The blue arrows indicate that during lesson enactment, the teacher has authority over the students via the chalkboard. Because of the teacher and chalkboard’s active role in making mathematics accessible to students, the distance between teacher, chalkboard, and mathematics is closer to one another than to the students.

Also in MiF (USA), the teacher has authority over the students, as indicated by the blue arrows. Both the teacher and textbook have an active role in making the mathematics accessible to the students, thus the teacher, textbook, and mathematics are closer together than either is to the students. The double-sided green arrow is indicative for the teacher and lesson guide’s sharing of authority during lesson planning.

In EM (USA) as well, the double-sided green arrow is indicative for the teacher and lesson guide sharing authority during lesson planning. The double-sided blue arrow is indicative for the teacher’s and students’ sharing of authority during lesson enactment. Because the teacher and students together establish the connection to mathematics, the distance between students, teacher, and mathematics is closer than it is to the textbook.

The green arrow from teacher to lesson guide for ME and MD (Sweden) is indicative of the teacher having authority over the lesson guide during lesson planning. The double-sided blue arrow represents the shared authority between the students and their textbook during lesson enactment. The blue lines without arrows represent a lack of indication of authority exercised by the teacher over the students or textbook. Because the students actively work with their textbook in accessing the mathematics, we drew the distance between student, textbook, and mathematics closer together than the relationships to the teacher.

8 Discussion

8.1 Analyzing the pervasive and hidden nature of configured social relations

We have presented and illustrated an analytical approach to study how lesson guides, through their multimodal design, communicate messages about the configuration of social relations—or how the teacher and students are positioned in relation to one another, to central artefacts, and mathematics itself. We have argued for an understanding of these configured social relations as cultural scripts that guide the teachers’ behavior and set their expectations toward the other nodes in the didactical tetrahedron. Such scripts build on a limited set of tacit beliefs about teaching and learning mathematics, requiring one to consider these motives when studying cultural scripts (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999). To incorporate the motives of the configured social relations in our multimodal analysis, we drew on activity theory by studying the rules of authority and division of labor in the intended classroom. The combination of the multimodal and activity-theoretical lenses allowed us to characterize the social relations in terms of authority and distance.

Analyzing lesson guides from textbook series from three educational contexts in such a way and visualizing the configured social relations has revealed clearly distinct patterns in what the teacher is expected to do and what she or he should expect from the other nodes. These patterns differ primarily across the three educational contexts, supporting our argument that the configuration of social relations in lesson guides is a cultural script. From the Flemish lesson guides, teachers should carefully follow these guides to steer students through the content on the chalkboard. The teacher, in turn, should expect the students to learn mathematics primarily by following her or his descriptions at the chalkboard. From the American lesson guides, teachers should follow the guidelines to structure instruction and classroom discussion. But they should also make their own decisions, for which they find related support in the lesson guide. For MiF (USA), the teacher should expect the students to learn mathematics by going through the content in the textbook, steered by the teacher. For EM (USA), students are expected to learn mathematics by actively participating in classroom interactions with their peers and the teacher. From the Swedish lesson guides, teachers should draw on some information from the lesson guide, but primarily on their own expertise to facilitate the student—textbook interaction. The teacher, in turn, should expect students to engage actively with the content in their textbook.

The deep analysis of the lesson guides’ communication of social relations aligns with the surface descriptions of the two Flemish and two American textbook series in Sect. 5. These within context similarities and cross-context differences could be anticipated. The differences in distance found between the two American guides can be explained by the different origins of the two programs. As we described in Sect. 5, MiF (USA) was adapted from a textbook used in Singapore, while EM (USA) was designed to follow the NCTM Standards. The similarity between lesson guides from the two Swedish textbook series was remarkable. MD (Sweden) was chosen because it represented the traditional approach to teaching and learning mathematics; ME (Sweden) was chosen because it was more innovative in the specific manner it provided teacher support and because it was specifically designed to follow the new curriculum. Our visualizations of the configured social relations show however how similar these two textbook series were. This finding points at the pervasive and hidden nature of the configured social relations. When curriculum authors adopt common conventions for designing the lesson guides to communicate to teachers, they are following a cultural script and reinforcing expectations about the social relations already at play. Thus, promoting change by following the scripts of lesson guides has limitations. Instead, the scripts themselves need to change. The first step in such a change is for the existing scripts and their motives to become noticed. Combining analytical tools grounded in both multimodality and activity theory has allowed us to surface these tacit messages and make visible the mechanisms used in lesson guides for communicating them.

8.2 Adding authority and distance to the didactical tetrahedron

We have identified two primary ways by which the multimodal communication in lesson guides configures social relations: by specifying authority within these relations, and by positioning the nodes in the didactical tetrahedron in closer or more distant proximity to one another. By incorporating authority and distance into the didactic tetrahedron, our analysis offers one approach to defining critical characteristics of the segments that Rezat and Sträßer (2012) identified as not yet characterized. Whereas the notion of authority relations in mathematics classrooms and in curriculum resources has been discussed in the literature (e.g., Amit & Fried, 2005; Herbel-Eisenmann, 2007; Morgan, 1996), the notion of distance, to our knowledge, has not. Our analysis suggests that, while closely related to authority in the mathematics classroom, distance communicates messages about the nature of mathematics teaching and learning in classrooms, including the role of various participants. As described above, when the teacher and artefacts are positioned centrally and in close relation to one another, the student becomes less active in the learning interaction. In contrast, when the primary interaction is between the teacher and students, or between students and the textbook, different learning dynamics are being ordered. Imposing the dimension of distance on the segments in the didactical tetrahedron offers a reminder that, while all nodes in the tetrahedron must be considered, in any teaching and learning situation, they are rarely engaged in equivalent ways. Thus, the notion of distance offers specific ways that the didactical tetrahedron might be used as an analytical tool.

That said, we also see limitations in how we have conceptualized and visualized distance. Our approach did not impose any degrees of activity in accessing the mathematics any other than active/less active. Neither did we use particular standards of length to set off distant from less distant relations. We have tried to balance this lack in precision of measurement by means of describing as accurately and detailed as possible what we have observed and how we came to characterize authority and distance. Yet, there is potential for future studies to further develop the reliability of this analytical approach.

9 Future opportunities for studying social relations

In the first paragraph of the introduction, we described the configuration of social relations in lesson guides as one way by which curriculum resource designers attempt to have leverage over the enacted curriculum. The present study, of course, does not permit us to speak to how the lessons actually unfold when they are placed in the hands of teachers. But our study underscores the need for additional questions to be posed in studies of how classroom enactment unfolds. The unfolding of the curriculum enactment process has primarily been studied from a content perspective (Fan et al., 2013). Our study stresses the need to also consider the nature of the social relations as classroom enactment unfolds. Related questions to be posed are: “How do students have access to mathematics?”, “Who does what in the classroom?”, “Where is authority located?”, and “Who is active/less active in connecting the students to the mathematical content?”.

Furthermore, our analysis drew on lesson guides that were in use about 10 years ago when we started this study. Contemporary textbooks and lesson guides appear more often in digital formats. The digital format has been related to specific modes of communication, such as video and connectivity, extending the possibilities for configurations of social relations and indicating that the study of configured social relations in digital curriculum resources would be a valuable line of future research.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [HVS], upon reasonable request.

Notes

The first author’s mother tongue is Dutch, he also speaks Swedish and English. The second author’s mother tongue is English.

References

Amit, M., & Fried, M. N. (2005). Authority and authority relations in mathematics education: A view from an 8th grade classroom. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 58(2), 145–168.

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in Multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication, 25(2), 166–195.

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2015). Multimodality, learning and communication: A social semiotic frame. Routledge.

Boesen, J., Helenius, O., Bergqvist, E., Bergqvist, T., Lithner, J., Palm, T., & Palmberg, B. (2014). Developing mathematical competence: From the intended to the enacted curriculum. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 33, 72–87.

Clarke, D. (2006). Using international research to contest prevalent oppositional dichotomies. ZDM – The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 38(5), 376–387.

Engeström, Y. (1998). Reorganizing the motivational sphere of classroom culture: An activity-theoretical analysis of planning in a teacher team. In F. Seeger, J. Voigt, & U. Waschescio (Eds.), The culture of the mathematics classroom (pp. 76–103). Cambridge University Press.

Fan, L., Zhu, Y., & Miao, Z. (2013). Textbook research in mathematics education: Development status and directions. ZDM – The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 45(5), 633–646.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. London Arnold.

Herbel-Eisenmann, B. A. (2007). From intended curriculum to written curriculum: Examining the “voice” of a mathematics textbook. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 38(4), 344–369.

Herbel-Eisenmann, B. A., & Wagner, D. (2007). A framework for uncovering the way a textbook may position the mathematics learner. For the Learning of Mathematics, 27(2), 8–14.

Jewitt, C. (2009). An introduction to multimodality. In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp. 14–27). Routledge.

Love, E., & Pimm, D. (1996). ‘This is so’: a text on texts. In A. J. Bishop, K. Clements, C. Keitel, J. Kilpatrick, & C. Laborde (Eds.), International handbook of mathematics education (Vol. 1, pp. 371–409). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Morgan, C. (1996). “The language of mathematics”: Towards a critical analysis of mathematics texts. For the Learning of Mathematics, 16(3), 2–10.

NCTM. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. NCTM.

Otte, M. (1983). Textual strategies. For the Learning of Mathematics, 3(3), 15–28.

Pepin, B., Choppin, J., Ruthven, K., & Sinclair, N. (2017). Digital curriculum resources in mathematics education: Foundations for change. ZDM – Mathematics Education, 49(5), 645–661.

Pepin, B., & Haggarty, L. (2001). Mathematics textbooks and their use in English, French, and German classrooms: A way to understand teaching and learning cultures. ZDM – The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 33(5), 158–175.

Remillard, J. T., Van Steenbrugge, H., & Bergqvist, T. (2014). A cross-cultural analysis of the voice of curriculum materials. In K. Jones, C. Bokhove, G. Howson, & L. Fan (Eds.), Proceedings of international conference on mathematics textbook research and development (pp. 395–400).

Remillard, J. T. (2012). Modes of engagement: Understanding teachers’ transactions with mathematics curriculum resources. In G. Gueudet, B. Pepin, & L. Trouche (Eds.), From text to ‘lived’ resources (pp. 105–122). Springer.

Remillard, J. T., & Kim, O.-K. (2020). Elementary mathematics curriculum materials: Designs for student learning and teacher enactment. Springer Nature.

Rezat, S., & Sträßer, R. (2012). From the didactical triangle to the socio-didactical tetrahedron: Artifacts as fundamental constituents of the didactical situation. ZDM – The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 44(5), 641–651.

Van Steenbrugge, H., & Bergqvist, T. (2014). Mathematics curriculum programs as tools for design: an analysis of the forms of address. Paper presented at the AERA annual meeting, Philadelphia, USA.

Van Steenbrugge, H., Krzywacki, H., Remillard, J. T., Machalow, R., Koljonen, T., Hemmi, K., & Yu, Y. (2019). Mathematics curriculum reform in the U.S., Finland, Sweden and Flanders: Region-wide coherence versus teacher involvement? In M. Graven, H. Venkat, A. Essien, & P. Vale (Eds.), Proceedings of the 43rd conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (Vol. 3, pp. 406–413). PME.

Stigler, J., & Hiebert, J. (1999). The teaching gap: Best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving education in the classroom. The Free Press.

Valverde, G. A., Bianchi, L. J., Wolfe, R. G., Schmidt, W. H., & Houang, R. T. (2002). According to the book: Using TIMSS to investigate the translation of policy into practice through the world of textbooks. Kluwer.

Verschaffel, L. (2004). All you wanted to know about mathematics education in Flanders, but were afraid to ask. In R. Keijzer & E. de Goeij (Eds.), Rekenen-wiskunde als rijke bron [Mathematics education as a gold mine] (pp. 65–86). Freudenthal Instituut.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Tomas Bergqvist, who was involved in the coding of the written communication at the beginning of this study, as well as the colleagues of the SOCAME research group at Stockholm University for comments on earlier versions of this paper. We also thank the reviewers for thoughtful comments that pushed us to further develop our thinking.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Steenbrugge, H., Remillard, J.T. The multimodality of lesson guides and the communication of social relations. ZDM Mathematics Education 55, 579–595 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-023-01479-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-023-01479-2