Abstract

In this survey paper we aim to provide an overview of research on mathematics textbooks and, more broadly, curriculum resources as instruments for change related to mathematical content, instructional goals and practices, and student learning of mathematics. In particular, we elaborate on the following themes: (1) The role of curriculum resources as instruments for change from a theoretical perspective; (2) The design of curriculum resources to mediate the implementation of reform ideas and innovative practice; (3) Teachers’ influence on the implementation of change through curriculum resources; (4) Students’ influence on the implementation of change through curriculum resources; and (5) Evidence of curriculum resources yielding changes in student-related factors or variables. We claim that, whilst textbooks and curriculum resources are influential, they alone cannot change teachers’ teaching nor students’ learning practices in times of curricular change. Moreover, more knowledge is needed about features of curriculum resources that support the implementation of change. We contend that curriculum innovations are likely to be successful, if teachers and students are supported to co- and re-design the relevant curriculum trajectories and materials in line with the reform efforts and their own individual needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

One of the main concerns of mathematics education research is to improve mathematics education practice. In educational systems around the world, mathematics textbooks and, more broadly, curriculum resources are widely regarded as instruments for the implementation of change in mathematics classrooms (Cai & Howson, 2013; Keitel et al., 1980; Remillard, 2005; Senk & Thompson, 2003). One of the aims of this special issue is to draw particular attention to this power attributed to textbooks and curriculum resources.

Leaning on the work of Pepin and Gueudet (2018) and Remillard (2018), we use the term curriculum resources to include textbooks, and we define the term for our purpose as the print or digital materials designed to support teachers’ teaching and students’ learning; they are materials that have been developed (e.g., by an institution) for achieving particular curricular goals. The adjunct ‘curriculum’ indicates particular attention to the sequencing “of grade-, or age-level learning topics, or of content associated with a particular course of study (e.g., algebra)—so as to cover (all or part of) a curriculum specification”, as suggested by Pepin et al., (2017, p. 647). Similarly to Pepin and Gueudet (2018), we regard analogue and digital mathematics textbooks as a key part of a set of curriculum resources.

From a survey of the literature, we identified the following three objects of change through curriculum resources:

-

1.

Curriculum resources are used as instruments to change the mathematical content that is taught and the objectives of teaching mathematics. (Keitel et al., 1980; Remillard, 2005; Valverde et al., 2002)

-

2.

Curriculum resources are designed to implement instructional change in mathematics classrooms (e.g., innovative classroom practices; different pedagogical approaches for the learning of mathematics) (Senk & Thompson, 2003).

-

3.

Curriculum resources define mathematics as a school subject for students. They communicate a vision of mathematics and impact how students experience (and perceive) mathematics. Therefore, they are used as instruments to enhance students’ knowledge and change their beliefs and attitudes related to mathematics (Cai & Howson, 2013).

We refer to all attempts to change the mathematical content, the objectives for teaching and learning of mathematics, the pedagogy and classroom practices as matters of reform. In order to serve these purposes, reform ideas need to be incorporated in the design of curriculum resources in terms of the selection, progression and coherence of contents and activities, the structure, and the layout. Therefore, curriculum resources also become the object of change themselves.

In this survey paper, we provide an overview of research on curriculum resources as instruments for change. Our guiding questions are as follows:

-

(1)

How is the role of curriculum resources as instruments for change theorized?

-

(2)

How are curriculum resources designed to mediate the implementation of reform ideas and innovative practice?

-

(3)

How do teachers influence the implementation of change through curriculum resources?

-

(4)

How do students influence the implementation of change through curriculum resources?

-

(5)

What evidence is there of curriculum resources yielding changes in student related factors or variables?

In the subsequent sections, using our conceptualisation of curriculum resources (to include textbooks), we were guided by the five research questions in narratively reviewing the literature, and by doing so, we also hope to provide a pertinent background in terms of relevant literature to the readers of the special issue. We conclude this paper by summing up the relevant issues and outlining lessons learned from research on mathematics curriculum resources as mediators of change, and we indicate future directions for research.

2 Theorizing the role of curriculum resources as instruments for change

In this section, we give a brief historical overview of how curriculum resources became instruments for change, and we review the literature in terms of how the role of mathematics curriculum resources has been theorized within educational systems and how this role contributes to their function as instruments for change.

2.1 Some historical remarks on the role of curriculum resources as mediators of change

Historically, the ancient mathematics textbooks, such as the Euclid’s The Elements in the West (about 300 BC) and The Nine Chapters on Mathematical Art in the East (about 200–100 BC), had long served as supporting materials for the implementation of teaching and learning of mathematics (Fan et al., 2013). It is less clear how mathematics textbooks, if any, were specifically designed and used in ancient history as mediators for change or reform in teaching and learning mathematics, which is an issue worth further investigation by mathematics educators and historians.

However, in the last few centuries scenarios of mathematics textbooks and curriculum resources as mediators of reform have gradually become visible in many countries. For example, in the education reform plan of La Chalotais in mid eighteenth century’s France, good textbooks, instead of teacher training, were viewed as essential means for the success of reform, a position that was held into the early nineteenth century in the country (Schubring, 2003; Schubring & Fan, 2018). In the twentieth century, the role of mathematics textbooks as a supporter or mediator of reform has been increasingly recognized. This is most evident in the new math reform movement in the United States, or modern mathematics movement as it is commonly called in the UK, France and many other countries (D'Ambrosio, 1991; Thwaites, 2012), both starting in the late 1950s or early 1960s. In fact, several well-known school mathematics textbook series during this period of reform, for example, one produced by the School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG) in the US, and another by the School Mathematics Project (SMP) in the UK, were designed to implement the reform ideas of school mathematics. Another well-known example, though more influential at the university level, is the Bourbaki school and their works in France (Dieudonné, 1973; Marmier, 2014). In these reforms, what was mediated through curriculum resources focused more on the content, the structure, and the methods of mathematics (Cockcroft, 1982; Herrera & Owens, 2001).

As in the US and many other countries, after the new mathematics movement came to its end in the late 1970s, another dimension of mathematics teaching and learning, i.e., pedagogical approaches, received increasing attention in mathematics education reform. They are primarily about how to present mathematics knowledge and skills to learners and how to organize instructional activities in the teaching and learning of mathematics. Accordingly, new mathematics curriculum resources were produced to promote the implementation of those reform ideas. The textbooks produced based on these reform principles are sometimes simply called “reform textbooks” or “reform-oriented textbooks” in contrast to traditional textbooks (Martin et al., 2001; Park, 2011), an indication of the role of textbooks as mediators of reform. Two such examples are the UCSMPFootnote 1 textbooks in the US and the RMEFootnote 2-oriented textbooks in the Netherlands. The former emphasized, among other reform ideas, cooperative learning, use of technology and student-centered learning approaches (Fan & Kaeley, 2000; Usiskin, 1986), while the latter emphasized “that mathematics is not seen as ready-made knowledge but as an activity of the learner” (van Zanten & van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, 2021, p. 1) and learning of mathematics is essentially viewed as a process of “guided reinvention” (Freudenthal, 1991). It seems clear that curriculum resources, especially textbooks, will likely continue to be seen and used as mediators of reform and change (see more discussion below).

2.2 Conceptualizing the role of curriculum resources as instruments for change

In this section we aim to answer our first guiding question ‘How is the role of curriculum resources as instruments for change theorized?’ by summarizing frameworks in which the role of curriculum resources within the educational system has been theorized. A frequently cited curriculum framework was proposed by Travers and Westbury (1989) associated with the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). In this framework the authors distinguished between different curriculum representations, namely, the intended, the implemented, and the attained curriculum. Associated with the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSSFootnote 3) (Schmidt et al., 1997; Valverde et al., 2002) textbooks were added to this framework. Textbooks (and more generally curriculum resources) were seen as mediators between the intended and the implemented curriculum, and hence were conceptualized as the potentially implemented curriculum (Schmidt et al., 1997). Other frameworks built on the TIMMS-curriculum framework (e.g., Remillard & Heck, 2014) and differentiated further within the different levels of curriculum. These frameworks share that curriculum resources mediate between an officially sanctioned level of the curriculum and a level that is operationalized through practice. This perspective includes that curriculum resources can be regarded as an “intermediate variable” (Fan, 2013, p. 771) that on the one hand is subject to influences by independent variables (i.e., factors affecting the design and development of textbooks, such as national policy, social background and cultural values), and on the other hand influences dependent variables (i.e., factors affected by textbooks, such as teaching, learning, and student achievement).

This particular role of curriculum resources within the different levels of curriculum emphasises the potential of curriculum resources to support the ‘transmission’ of reform ideas from the officially intended curriculum, the level of curriculum policy, to the enacted (and possibly the attained) curriculum, represented as opportunities to learn in the classroom.

The implementation of instructional change through curriculum resources is not a straightforward process. Educational leaders and policy makers can play an important part in influencing the mediation of classroom reform through textbooks and curriculum materials. For example, as Fan and Kaeley (2000) have argued, “by choosing appropriate types of textbooks, the policy makers can influence the [reform] practice of mathematics teaching in classrooms, which in turn may help to improve mathematics standards in schools” (p. 8). As a matter of fact, at the national level of many countries, government leaders and policy makers can decide on the approval of particular textbooks for their state schools (e.g., in China), leave a free market (e.g., in France, UK), or exercise a combination of both (e.g., in Germany). However, even though there might be a ‘free market’, levers to implement reform efforts can come in different forms. For example, in France, often inspectors are part of a textbook author team, which is likely to ensure that the textbooks are in line with ministerial guidelines. Government leaders and policy makers can also decide on how textbooks should be produced, adopted and made accessible to students. At local and school level, policy makers and school leaders can decide on the selection of textbooks, and they can also influence teachers’ appropriation and practice of using textbooks in schools. There is no doubt that teachers’ use of textbooks is influenced by national or regional education policy and school culture.

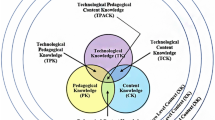

On the level of the enacted curriculum, the relationship between textbook content and the enacted curriculum is widely regarded as being dependent on how teachers and students interact with the curriculum resources in use. This view is grounded in a socio-cultural perspective, in which curriculum resources are conceptualized as artefacts that mediate within goal-directed activity (e.g., Brown, 2009; Rezat & Sträßer, 2012). At the micro-level, Rezat and Sträßer (2012) described this activity by means of the didactical tetrahedron, comprising teachers, students, mathematics, and textbooks as the major constituents of the didactical situation. From this perspective, innovation and reform ideas in curriculum resources have the potential to influence the teaching and learning of mathematics by affording or constraining teachers’ and students’ activities of teaching and learning mathematics. How this potential is unfolded depends on how users are able to access the values and ideas encoded in the curriculum resources. Therefore, Adler (2021, this special issue) argues that access to a (reform) practice is not solely provided through the curriculum resources, but requires additional forms of participation with them.

The mediatory role of curriculum resources at different levels of the educational system is depicted in the model in Fig. 1. The mediatory role of curriculum resources on the level of the classroom is shown by the didactical tetrahedron (Rezat & Sträßer, 2012). Besides the direct mediation of innovation and reform made accessible to teachers by means of professional development, curricular resources are used as mediational means to mediate curricular reform in classroom practice.

3 Curriculum resources as mediators of change for teaching and learning

As pointed out in Sect. 2, it is widely accepted that the relationship between curriculum resources and their users is a participatory relationship in which curriculum resources as artefacts afford and constrain the activities they mediate. Thus, in this section we seek to answer question (2) of how curriculum resources are designed to mediate the implementation of reform ideas and innovative practice.

3.1 Incorporating reform ideas in the design-features of curriculum resources

As Brantlinger (2011) pointed out, the particular challenge in designing curriculum resources for implementing reform and innovation is “the development of appropriate resources and curricular ideas to implement positive change as theorized by the advocates” (p. 397). Design principles have to be developed that help to translate the reform ideas into the structure, contents, tasks, and voice (Remillard, 2012) of curriculum resources. At the same time, these newly designed curriculum resources need to be “sufficiently flexible to be used in a diverse range of classroom settings yet sufficiently resilient to retain the core principles of the reform “ (Brown, 2002, p. 13).

In the case of the design of a reform mathematics curriculum document in Greece, Potari et al. (2019) showed that the implementation of reform through curriculum resources is a complex socio-cultural activity, which is not only influenced by those involved and the mediational artefacts such as curriculum documents or other resources representing the reform ideas, but also by contradictions evoked by the different activity systems of educational policy makers, teachers, and researchers involved in the design team. Applying the results reported by Potari et al. (2019) to the design of curriculum resources, it is likely that different design teams solve the contradictions differently, which yields different manifestations of the reform ideas in different curriculum resources. Van Zanten and van den Heuvel-Panhuizen (2021) showed that this is actually the case for textbooks implementing Realistic Mathematics Education (RME). They further reported that the implementation of reform ideas in textbooks changes over time.

In the research literature we find that the design of curriculum resources that are supposed to mediate reform is based mainly on normative or theoretical assumptions about how reform is conveyed through the structure, the selection and arrangements of contents and tasks. The introduction of design-research in the 1990s as an alternative to the traditional Research-Development-Dissemination-Model (RDD-model) of curriculum innovation has increasingly affected the development of curriculum resources. This method allows the combination of instructional design and educational research, particularly in contexts of innovation and reform, where “learning goals are to be refined in the process, little academic knowledge is available, and general theories do not yet offer much help” (Prediger et al., 2015, p. 878). There have been selected iconic projects, in which curriculum resources have been developed either explicitly within a design-research approach or in a close relation of scientific grounded design and empirical evaluation, such as The University of Chicago School Mathematics Project (UCSMP) (https://ucsmp.uchicago.edu), The Connected Mathematics Project (https://connectedmath.msu.edu) in the US, or the KOSIMA-Project (http://www.ko-si-ma.de) in Germany. In these projects, mathematics textbooks were developed on a research base and refined in ongoing cycles of formative evaluation (Burkhardt & Schoenfeld, 2020). An overview of the KOSIMA-project is provided by Prediger et al. (2021) in this special issue. This is a rare example that shows how design principles for a reform-textbook are constantly evaluated and improved in design research cycles. On a meta-level, Prediger et al. (2021) provide an example of how an interventionist rather than a descriptive research base for textbook design can be established by combining different research approaches. This paper outlines an approach that could be paradigmatic for designing reform curriculum resources in the future.

Rarely is the design of reform curriculum resources described and justified in detail in the literature. Some of the few exceptions are Hayen (1987) for a German textbook series and Confrey (2016) for a US digital curriculum resource. How reform ideas are implemented in curriculum resources is usually investigated a-posteriori through content analysis of the materials (e.g., Remillard & Kim, 2020).

There is a plethora of research on specific elements that are typically incorporated in the structure of curriculum resources, such as tasks (e.g., ZDM – Mathematics Education special issue Mathematical Tasks and the Student 49(6); Johansson, 2007; Watson & Ohtani, 2015; Yerushalmy, 2015; Yerushalmy et al., 2017), worked examples (e.g., Renkl, 2017), and diagrams (e.g., Naftaliev & Yerushalmy, 2013). It is not possible to give an overview of how change is promoted through the alteration of these particular elements of curriculum resources within this survey. The aim of this body of research is the investigation of the effect of particular design features of curriculum resources in isolation, and such research does not relate this aim to the structure or overall pedagogical approach associated with a curriculum resource. Research that analyzes how the different elements of a curriculum resource play together as a whole and how this influences the participatory relationship with its users is rare. The only exceptions are evaluation studies, which investigate the effects of curriculum resources as a whole in conjunction with their implementation in the teaching–learning process on students’ achievement and other student variables (see Sect. 5.2).

One design variable that cuts across the entire material related to mediating reform, and with which research has been repeatedly concerned, is textbook structure. As Valverde et al. (2002) argue, the structure of textbooks advances a particular pedagogical model, i.e., textbooks “embody a plan for the particular succession of educational opportunities considered optimal for enacting curricular intentions” (p. 54). Therefore, textbook structure is also particularly relevant for mediating curricular reform. Textbook authors and designers have therefore argued for particular structural decisions. For example, Saxon, the author of a reform first-year algebra textbook in the early 1980s for junior college students, claimed “that the structure of modern texts, namely chapters and chapter subdivisions and/or units, provide for an uneven and abrupt flow of new information” (Johnson & Smith, 1987, p. 98). Therefore, his algebra textbook consisted only of lessons. Usiskin (1986) argued that in the UCSMP textbooks real-world applications were used as motivation, and that they built the foundation for problem solving, which already superimposes a particular structure. Leuders et al. (2011) derived the structure of their mathematics textbook series for lower secondary grades (“die mathewerkstatt”) from their vision of mathematics, pedagogical theories and design principles. However, rarely is it explained how pedagogical models have informed the structure of mathematics textbooks, and how these pedagogical models actually influence the teaching and learning of mathematics is scarcely investigated (Remillard & Kim, 2020).

Only recently has research tried to unravel how the participatory relationship between teachers and curriculum resources in designing instruction is shaped by features of the materials. Choppin et al. (2020) analyzed enactments of the US Common Core State Standards Mathematics (CCSSM) curriculum, in terms of rigor of mathematical activity across middle school mathematics lessons in several states and across different curriculum contexts. In order to characterize the instructional materials, the authors distinguished two contrasting sets of design features that they regarded as two opposed endpoints of a conjectured continuum of design perspectives: curriculum resources are characterized either as delivery mechanism or as thinking device. These two types of materials differ in the ways they develop terminology and procedures, in the nature of tasks, and in the sequencing of collections of problems or tasks within a lesson. Their results indicate that non-routine forms of rigor were found only in classrooms using materials classified as thinking devices. Thus, the authors concluded that the features of the curriculum resources influence the nature of mathematical activity in the classrooms. These results are deepened by Choppin et al. (2021, this special issue). In this study they analyzed how linguistic aspects of the curriculum resources influence teachers’ planning of lessons, by comparing the lessons planned by the same teacher for the same topic, but with different materials. They found indications that the planned activities were influenced by the materials.

3.2 Scaffolding implementation of reform through the design of curriculum resources

As pointed out in Sect. 2, the implementation of innovation and reform is largely dependent on teachers as users of the curriculum resources. In their study of how Swedish teachers interact with and reason about the reform-based classroom practices promoted by the curriculum program and teachers’ guide, van Steenbrugge and Ryve (2018) concluded that “characteristics of current classroom practices, teachers’ role in classrooms, the history of implicit/explicit teacher support, and teachers’ experiences using teachers’ guides, explain how teachers interact with and reason about the curriculum program, and therefore are crucial when designing a new research-based mathematics curriculum program” (van Steenbrugge & Ryve, 2018, p. 811).

To support the implementation of reform ideas in curriculum resources, researchers have investigated ways of scaffolding teachers’ understanding and enactment of content and pedagogy. This research has given rise to the notion of curriculum resources that are ‘educative for teachers’ (Ball & Cohen, 1996) and ‘educative curriculum materials’ (Davis et al., 2017; Pepin, 2018), in which the adjunct ‘educative’ refers to teachers as learners and denotes that these curriculum resources are designed “to help to increase teachers’ knowledge in specific instances of instructional decision making but also help them develop more general knowledge that they can apply flexibly in new situations” (Davis & Krajcik, 2005, p. 3). This perspective implies that authors communicate to teachers instead of communicating through them in terms of directing action (Remillard & Kim, 2020, p. 261). In mathematics education, educators have started to develop and evaluate specific design principles for educative curriculum resources in the domain of mathematics. For example, Pepin (2018) outlined functions and design specifications of (mathematics education) educative materials. Prediger et al., (2021, this special issue) add to this by describing how obstacles in supporting teachers in enhancing processes of mathematization and active knowledge organization by means of a textbook were overcome by the development of new types of tasks within a design-research project.

3.3 Digital curriculum resources

The implementation of innovation in curriculum resources in terms of new possibilities for changing students encounter with mathematics is also closely linked to the development of digital curriculum resources. The potentials of increased possibilities for multimodal representations of mathematics, interactive elements, and possibilities for communication and cooperation, are often highlighted in this context (e.g., Choppin et al., 2014). However, translating traditional paper into digital curriculum resources is not a straightforward process. Already the change of representation mode from paper to digital screen gives rise to challenges and affects the representation of content and thus is likely to change students’ encounters with mathematics. For example, content that could be surveyed easily on the two pages of a paper curriculum resource needs to be cut down into smaller pieces and rearranged to fit the screen (Usiskin, 2018). Additionally, the affordances of the digital resources have given rise to the implementation of new elements in digital curriculum resources (Choppin & Borys, 2017; Pepin et al., 2016), such as interactive diagrams (Naftaliev & Yerushalmy, 2013; Yerushalmy, 2005), feedback (Rezat, 2021, this special issue), learner-controlled scaffolding (Edson, 2017), and communication links between teachers, students and parents, to name but a few possibilities. These new possibilities of digital curriculum resources have also attracted researchers to develop a deeper understanding of particular design features or elements of curriculum resources and how they affect the teaching and learning of mathematics. The challenge remains to integrate these new features in the design of e-textbooks in a way that these “genuinely can be more than the sum of the parts” (Bokhove, 2017, p. 113). In this special issue, several papers address the development and use of special features of digital curriculum resources. Edson and Difanis Phillips (2021, this special issue) describe the development of a teacher dashboard in a digital collaborative curriculum resource as a means to support teachers in implementing a problem-based curriculum. This study exemplifies the importance of considering teachers’ use and needs when implementing change with digital curriculum resources in the iterative development of the teacher dashboard. Mesa et al., (2021, this special issue) analyzed teachers’ use of questioning devices as specific e-textbook elements. They found four types of interdependent utilization schemes in which the questioning devices were instruments for teacher activity. Confrey and Shah (2021, this special issue) analyzed how teachers participated with classroom assessment data and how this affected their instruction with learning trajectories.

As Adler (2021, this special issue) argues, “the unproblematic integration of new resources into cultural practices, does not lie in the resource itself”. There are many other factors that influence to what extent and in what ways curriculum resources can act as a mediator of reform, within certain social and cultural contexts and practices. Among them, we can identify, from the available research literature, some key factors—in the first place, teachers and students—all of which interplay with the implementation of reform through curriculum materials.

4 Teachers as mediators of change through curriculum resources

In their seminal paper, Ball and Cohen (1996) proposed to “redraw the boundaries between teacher and materials in the construction of the curriculum”. They argued as follows:

We see no alternative if curriculum is to play a more constructive role in improving instruction, for the curriculum that counts is the curriculum that is needed. If we want the intended curriculum best to contribute to the enacted one, we must find ways to design the first with the second clearly in view. That cannot be done without framing curriculum use and construction as activities that draw on teachers’ understanding and students’ thinking, and that depend on engaging ways to represent the material and develop the intellectual environment of the class. (p. 8)

Teachers are crucial when it comes to curriculum renewal, as they are the ones to enact a new curriculum in their classrooms. Hence, teachers need to make sense of the new curriculum, to be professionally prepared for an appropriate use of ‘new’ subject matter and associated pedagogical knowledge (e.g., according to the level of their students’ education and grade level), and they have to be able to develop and appropriate the new curriculum resources in a suitable way (e.g., knowing about affordances and possible misconceptions).

In terms of benefits, it has been recognized that when teachers interact with curriculum resources, they ‘co-design’, whether it is lessons that they teach the next day, or for colleagues when working in a collective that develops lesson plans for the larger community in different design contexts. In that process they are said to develop curriculum expertise and knowledge, individually when preparing their lessons, and collectively in professional development sessions and other interactions with their colleagues. It has been shown that the collective dimension is an important aspect of teachers’ professional development and (design) capacity building (e.g., ICMI Study, 2020; Pepin et al., 2017; van Steenbrugge & Ryve, 2018).

Regarding contexts of teacher interaction with curriculum resources, beside their lesson planning at home, teachers work with colleagues in school, or across schools in local, regional or international professional development groups (e.g., ICMI Study, 2020), to design and adapt curriculum resources for their own teaching and that of their colleagues (Pepin et al., 2019). In particular, the design of e-textbooks has stirred particular attention (e.g., Essonnier et al., 2018; Pepin et al., 2016). Moreover, in some countries, platforms have been created, so that teachers can work collaboratively to design materials at a distance (e.g., Misfeld & Zacho, 2016).

In this section we report on the literature in terms of mathematics teachers’ use of and interaction with curriculum resources in relation to reform efforts, in order to answer the question (3) of how teachers influence the implementation of change through curriculum resources. The section is divided into two sub-sections: (1) types of ‘use’ by teachers; and (2) teachers as ‘designers’ of their own curriculum.

4.1 Types of ‘use’ by teachers

Many researchers have pointed out that teachers, as interpreters and users, play a crucial role in the use of curriculum resources in classroom (e.g., Stylianides, 2016). An early study conducted by Freeman and Porter (1989) who analyzed four teachers’ use of the same textbook in a school-year, revealed striking differences in these teachers’ content selection, time allocation, grouping practices and achievement standards. A more recent study by Thompson and Senk (2014) who studied 12 teachers’ use of a geometry textbook, also found that different teachers used textbooks differently.

Teachers used to be seen as the ‘implementers’ of the curriculum and the associated materials, which had been developed by professional curriculum designers and mathematicians. Consequently, the teacher’s role was that of the mediator of textbook content by means of following or subverting the text. The goal of implementation was close fidelity to the materials, which was conceived as ‘alignment’ with the curriculum (designers’) intentions. However, as many studies have shown that teachers use curriculum resources differently to prepare and set up their teaching in class, the relationship between teachers and curriculum resources is nowadays widely characterized as interactive and participatory (e.g., Remillard, 2005). So far, research has identified and described several patterns or types of interaction and also the factors that are likely to influence the interaction. The types of curriculum use are distinguished based on different aspects.

For example, Sherin and Drake (2009) analyzed patterns of teachers’ use of curriculum resources. They distinguished use before, during, and after instruction, and three different activities with the resources in each phase, namely, reading, evaluating, and adapting. They regarded adaptation to lie on a continuum, from omitting, through replacing, to creating new components. Related to amendments or omissions, Leshota and Adler (2018, p. 99) pointed out that these may be either ‘robust’ or ‘productive’ in that they either enhance the opportunities to learn or at least do not affect the mediation of the content such as ‘critical’ ones do. Brown (2009) distinguished three different types of ways that teachers appropriate curriculum resources in their teaching, namely, offloading, adapting, and improvising. Each of these types involves a different degree of distribution of the responsibility for instruction between the teacher and the materials. Lepik et al. (2015) distinguished four different groups of teachers based on the role they ascribed to the textbook: there were those who used textbooks in almost every lesson, those who did not treat textbooks as their primary tools in classroom use, those who would use the textbooks mostly for exercise and homework, and those who often let pupils study the new concepts from the textbooks.

In terms of aspects influencing the participatory relationship between teachers and curriculum resources, Haggarty and Pepin’s study (2002) with teachers in England found that experienced teachers tended to treat the textbooks as a source of ideas, while less experienced and non-specialist teachers would rely on the textbooks more heavily. Fan et al., (2021, this special issue) surveyed secondary teachers in Shanghai about how textbooks facilitate teaching. Their survey provides a differentiated view of how different aspects facilitate teachers professional work in the Chinese context. However, how their results are also applicable to other contexts is open to further inquiry. Kim (2018) analyzed how 11 elementary school teachers in the US sequence lessons and activities based on given curriculum resources. She was able to show that following or modifying the suggested sequence in the curriculum resource seems to be also dependent on characteristics of the particular program.

In summary, what we mean by ‘use’ of reform materials ranges from ‘alignment’ (e.g., ‘teaching by the book’), through ‘appropriation’ and ‘re-design’ (e.g., using curriculum resources to plan their lessons), to designing completely new materials (e.g., designing new materials after a curriculum reform). Available studies have more or less revealed that teachers’ motivation, knowledge, experience and even their cultural background, all have an effect in using curriculum resources as a mediator for reform. In recent years, this multifaceted understanding of teachers’ use of curriculum resources has led to the notion of teachers as ‘(co-)designers’ of their own curriculum in many western countries (e.g., Brown, 2009; Pepin et al., 2017). Due to the very different patterns and types of interaction with curriculum resources, teachers and their appropriation and adaption of curriculum resources in designing the enacted curriculum are a key factor in the implementation of change through curriculum resources. Nevertheless, according to Adler (2021, this special issue), there is an “inevitable gap between resources and their users”, which is shaped by the socio-cultural practices. Thus, an important issue for the implementation of change through curriculum resources is how teachers may be supported in their design in and for teaching.

Adler (2021, this special issue) argues that the “unproblematic integration of new resources into cultural practices, does not lie in the resource itself”, but in the socio-cultural practices that shape the teacher-resources relationship. This is mirrored in a growing attention to these socio-cultural practices in research on the implementation of reform through curriculum resources, which is also apparent in this special issue. First, Remillard et al., (2021, this special issue) examined teachers’ reflections on incorporating digital instructional resources into their mathematics instruction. They were particularly interested in how digital instructional resources might shift elements of teaching and learning in potentially transformative ways. The findings indicate that teachers tend to incorporate digital instructional resources in their existing socio-cultural practice and rarely transform typical learning spaces. In particular, participation in social media and resource sharing altered the nature of and ways teachers participate in their own professional learning. Second, Olsher and Cooper (2021, this special issue) show that the enactment of curricular change does depend less on the ‘new textbook’, but rather on teachers’ orientation towards the curriculum and its representation in the textbook. They have studied this by means of ‘didactic tagging’ of textbooks—a methodology where teachers assign metadata to textbook tasks. They could identify patterns of tagging which could be linked to each tagger’s interaction with the textbook.

Besides designing curriculum resources which are educative for teachers as outlined in Sect. 3.2, recent studies also focus on other ways that foster teachers’ participation in these socio-cultural practices that are regarded as conducive for reform intentions. For example, studies by Misfeld and his team (e.g., Misfeld & Zacho, 2016) have shown that the teacher platform offered to teachers in Denmark (by the ministry) was strongly linked to the Danish educational policies and national perspectives on teachers’ work with resources.

Three papers in this special issue in particular contribute to the issue of fostering teachers’ participation in socio-cultural practices that are conducive to the implementation of reform. Cai and Hwang (2021, this special issue) show how adaptation and improvisation can further be fostered through professional development in cases where textbooks do not yet provide the reform content in a sufficient way. Furthermore, there is a growing awareness of additional resources that might support the appropriation and adaption processes. Gueudet et al., (2021, this special issue) conducted a design-research study in order to develop and investigate how a meta-resource can support teachers’ implementation of reform efforts aimed at increasing students’ autonomy through the use of digital resources. Adler (2021, this special issue) exemplifies how a mathematics teaching framework as an ideational resource links the ‘inevitable gap’ between resources and teachers. The particular contribution of these studies to the field is that they identify important factors that are related to the gap between curriculum resources and their users, and draw attention to additional resources that support teachers to bridge this gap.

4.2 Teachers as designers of their own curriculum

Before we delve into how teachers might work as (co-)designers of their own curriculum in contexts of innovation and reform, we want to clarify the term ‘teacher design’. Pepin et al. (2019) investigated the notion of ‘teachers as curriculum designers’ (a) from a theoretical perspective (i.e., the literature) and (b) from six international perspectives, in order to develop a deeper understanding of the concept, and to be able to illuminate the different facets of teacher design. Theoretically, they identified the following aspects of what they called ‘teacher design’:

-

Intentionality: deliberate, goal-directed mental activity, definition of a clear goal;

-

(Degree of) novelty: positioned (on the continuum) between slight adaptations of current practices, to developing a new curriculum resource (e.g., textbook) or scheme of work from scratch;

-

Approach: strategies, styles, design approaches;

-

Time (duration): depending on the context, between hourly design session/s, to a long-term professional development design activity;

-

Individual/collaborative (‘teaming’): from individual teacher design (in school, or at home) to professional teacher design teams;

-

Audience/use: for one teacher’s own teaching; for all mathematics teachers in the school (site-specific design); for the whole regional/national teaching staff (generic design);

-

Context:

-

Design Space/environment: at home, school or internet

-

Resources: resources and tools available in the national/school context and used for the design.

-

These dimensions are important, in particular when discussing teacher curriculum design during times of curriculum reform. At these ‘delicate moments’ the intentions have to be clearly defined in relation to the curriculum reforms (aspect 1), and often original and new materials are asked for (aspect 2). In this special issue, Glasnović Gracin and Jukić Matić (2021) provide an example—though from a different theoretical perspective—of how these dimensions are intertwined in the context of implementing reform textbooks. They trace the use of a textbook by one Croatian teacher and her students before, during, and after the reform in order to identify changes in its use and the parameters that influence these. They find that the textbook remained a stable resource although the teacher increasingly gained autonomy from it. This case exemplifies how reform efforts, changes and developments in the textbook caused by the increasing offer of digital tools, and the increasing teacher expertise play together in the design of the implemented curriculum.

Results from Pepin et al. (2019) also showed that (at least) the following three different modes of teacher design can be distinguished empirically (d to denote design for own use; D to denote design for use by others), albeit not all modes were evident in all contexts: (1) teacher design activities at micro level (e.g., lesson preparation alone or in small groups for own use), (2) those at meso level (e.g., D/designing in collectives of colleagues for the purpose of use by others), and (3) teacher Design at macro level (e.g., involvement in the design of national frameworks designed in professional design teams for the use of many others). This is not to claim that teachers design similarly all over the world; quite the contrary, particular modes of design were evident in particular contexts, probably due to the affordances and constraints of the contexts (e.g., Lesson Study practices in Japan and China were associated with D/design, or Design activities in contexts where curriculum development agencies acted as mediators between the ministry prescribing the national curriculum and teacher enactment in schools). The cultural situatedness of textbook use by teachers is also evident in the study by Shinno and Mizoguchi (2021, this special issue) who present theoretical frameworks that pertain to the particular way Japanese teachers’ use their textbooks for lesson planning.

In the literature we can find many examples of these modes of design. At micro level, that is when teachers prepare their lessons alone or in small groups, they typically assemble a number of curriculum resources (including digital curriculum resources) around them, and appropriate the existing tasks and activities for their teaching (e.g., Bergsten & Frejd, 2019) in line with their own intentions and practices. This practice actually calls into question the role of curriculum resources and emphasizes the role of the teacher in the implementation of change. In this practice, it is not only one reform curriculum resource that is used. By relying on different materials with (potentially) different intentions it is even more the task of the teacher to design the enacted curriculum according to reform ideas. At the same time, this practice (using many curriculum resources for lesson design) is likely to foster teacher mindfulness and agency in the design process, which could (potentially) counteract alignment with and ‘simple enactment’ of the curriculum prescribed by the ministry. At meso level, that is when teachers design curriculum resources in collectives of colleagues for the purpose of use by others, they often (explicitly) refer to the national curriculum guidelines in relation to the curriculum resources they design. At macro level, that is when teachers are involved in the design of national frameworks designed in professional design teams for the use of many others, they are often guided by design experts, experts of particular technology tools (e.g., platforms) and/or curriculum (mathematics) didacticians (Choppin et al., 2014; Pepin, et al., 2017).

The levels of design identified above show that teachers do not only influence implementation of change through curriculum resources when designing their classroom instruction, but also on other levels. While in many countries teachers have been involved in the development of textbooks for a long time, relatively little research has investigated how teachers influence the implementation of change on these levels. Due to the rise of open educational resources (OERs) and other possibilities of offering curriculum resources on the internet, the attention to these levels is slowly rising.

5 Students, curriculum resources and change

Students are a target group of reform efforts. Implementation of change in mathematical classrooms is supposed to change students learning experiences and encounters with mathematics, and their mathematical attainment. However, as depicted in the socio-didactical tetrahedron in Fig. 1, they are not only the receivers of reform, but also active designers in the implementation of change through their interaction with the curriculum resources. Nevertheless, researchers have for a long time paid much more attention to issues concerning teachers’ use of curriculum resources (see Sect. 4), while studies on students’ use of curriculum resources have been scarce (Fan et al., 2013).

In this section, we focus on students as users of curriculum resources and examine how their participation in the activity depicted by the didactical tetrahedron in Fig. 1 influences the implementation of change and reform through curriculum resources. In order to answer the question (4) of how students influence the implementation of change through curriculum resources, we shortly summarize findings related to students’ use of curriculum resources. Moreover, we focus on students as the object of change through curriculum resources and provide an overview of empirical studies that emphasize the potential of curriculum resources to yield changes in student variables in order to answer question (5).

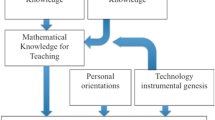

5.1 Student factors influencing the implementation of change through curriculum resources

Students’ use of curriculum resources for a long time has been widely regarded as a result of teachers’ use of curriculum resources; in other words, students’ use of curriculum resources is viewed as mediated by their teachers (Fan et al., 2004; Haggarty & Pepin, 2002). However, as with teachers, the relationship between students and curriculum resources can be conceptualized as one of mutual participation (Brown, 2009; Remillard, 2005; Rezat, 2013). Students carry their beliefs about mathematics and about learning mathematics, their previous knowledge, their literacy skills, and other personal resources to the interaction with curriculum resources, and these structure and influence how students use curriculum resources and learn mathematics (Rezat, 2013). Rezat (2011), showed that German students used mathematics textbooks not only under the guidance of their teachers but also for their self-directed learning. Nevertheless, self-directed use is also partly dependent on teachers’ use of textbooks in class, which serves primarily as orientation. Recently, a growing interest in students’ use of textbooks at different educational levels and in different cultural contexts is noticeable.

Different studies have identified purposes of secondary school students’ use of textbooks. Rezat (2009) found that German secondary school students use their textbooks for (1) finding support for solving tasks and problems, (2) consolidation, (3) acquiring mathematical knowledge, and (4) activities associated with interest in mathematics. Wang and Fan (2021) found that secondary school students in England and Shanghai used their textbooks for preview, revision, in-class learning, and exercises, and looking up information. In the tertiary context, Weinberg et al. (2011) find that students use their textbooks primarily with the goal of better understanding while completing homework and studying for exams. Using the textbook as a resource for understanding material from class session was much less common. In summary, these results provide evidence that curriculum resources are used by students, which is a prerequisite for students to come directly into touch with innovative and reform features of curriculum resources.

Additionally, all studies on students’ use of textbooks in secondary and tertiary contexts found that students use their textbooks selectively, i.e., they use different parts or particular structural components for different purposes. Rezat (2009) described that students select content from the book based on (1) the relative position, where particular information is expected (e.g., the explanation of a worked example is expected to be in an area close to the worked example; an introduction to a new concept is located at the beginning of a chapter); (2) the structural components or blocks (e.g., expository text, kernels in a box, worked examples, tasks and exercises); and (3) salience, i.e. surface features that indicate relevance for the reason of using the textbooks. In a survey of 1156 university students’ use of their textbooks in terms of purposes and structural components, Weinberg et al. (2011) found that students use the chapter introduction and chapter summary significantly less than the other components. The chapter text is also used less than the examples and exercises. Similarly, Randahl (2012) reports that students at tertiary level mainly focus on the tasks.

As outlined earlier, textbooks and curriculum resources in their structure, proposed activities, and sequencing of content, suggest a particular pedagogical model to their users (Rezat, 2006; Valverde et al., 2002). Weinberg et al. (2011) argue, that if the structure of the curriculum resource, the kind and order of proposed activities and the sequencing of the content define a particular pedagogical model in terms of stages through which the user must progress, then it would be important that students as the users of the curriculum resources use each component and progress through them in the suggested order. However, the above findings challenge the role of the pedagogical model as the different studies show that students at all levels are less likely to use the textbook lessons as intended by the authors, but selectively, and thus may not benefit from the progression as the authors had planned. The structure of the textbooks seems to afford a selective use of particular components or elements for certain needs.

Another important finding related to the issue of implementing change is that especially tertiary students do not rely on one single curriculum resource, but on a variety of curriculum and general resources for their learning and studying. For example, Anastasakis et al. (2017) who surveyed 201 second-year engineering students in mathematics courses found that the resources provided by the university and students own written notes were the most popular among the students, because these seemed to be the most promising for achieving high marks. It can be argued that in these first- and second-year courses, curriculum innovation is likely to have to go through the teacher’s choice of curriculum resources aligned with the goals of the course. However, in another study, Pepin and Kock (2021) turned to third-year students working on their ‘challenge-based’ bachelor end project (where students choose a ‘grand challenge’ (e.g., climate change), define their own project within that challenge, and work in multi-disciplinary teams). Results showed that the students working on these projects identified and used resources outside the realm of ‘pre-scribed’ curriculum resources offered to them in traditional courses. Here the students identified their own learning and study trajectories, with their own chosen curriculum resources (often supported by a coach). The curriculum innovation was prescribed by the university, to work on challenge-based bachelor end projects, and students ‘enacted’ the curriculum with self-chosen resources. Beside curriculum resources, social resources played an important role.

Furthermore, Wang and Fan (2021), in a comparison of Chinese and British secondary students’ use of textbooks, showed that students’ use of textbooks is dependent on social, educational, and cultural differences such as the role of textbooks in mathematics learning and how they are made available to students. While Shanghai students relied heavily on textbooks and used them in various situations, had a strong sense of self-regulation behind their use, and thought highly of textbooks in their learning of mathematics, this was not the case for their English counterparts. However, how these differences are related to the textbooks and to the socio-cultural practices in each country’s context is subject to further investigation.

Finally, with the growing availability of digital curriculum resources, and the advocation of active learning in education, it seems apparent that students will play a more important part in determining how much curriculum resources can contribute to their learning, an ultimate goal of education reform. These trends will challenge the development of curriculum resources. On the one hand, this trend will call into question the use of closed materials, which do not provide links to other resources; and on the other hand, providing coherency of learning trajectories will become a growing issue, when different curriculum resources are involved. Considering these developments, Pepin (2021, this special issue) proposes the notion of connectivity as a design principle and elaborates on how this may support students in their interaction with curriculum resources to plan and design their own coherent mathematics curriculum.

5.2 Curriculum resources and their effects on student variables

Given that the motives and the goals of the implementation of change in mathematics education through curriculum resources are directed at students, e.g., increasing students’ achievement, fostering their conceptual understanding, providing a positive attitude towards mathematics and the learning of mathematics, there is comparatively little research that focuses on student variables as an object of change through curriculum resources. The variables that have been investigated in previous research are (a) student achievement, and students’ conceptual understanding, (b) students’ beliefs, and (c) students’ participation in mathematics. By investigating the effects of curriculum resources on these variables the results of these studies are directly related to the issue of change, because if curriculum resources have an effect on these factors, this would be tantamount to curriculum resources having the potential to yield change in these variables.

5.2.1 Curriculum resources as instruments to change student achievement and conceptual understanding

In Sects. 2 and 4, we summarized studies that have shown that the enacted curriculum, and thus the enacted opportunities to learn for students, are highly dependent on teachers’ use of the resources as well as their orientations towards the resources, towards mathematics and how it is learned. Therefore, the extent to which curriculum resources themselves influence the enacted curriculum and student achievement has been questioned (Remillard et al., 2014). However, studies have shown that the opportunities to learn provided by curriculum resources have significant effects on student achievement (Schmidt et al., 2001, van den Ham & Heinze, 2018) and that these effects are even cumulative over the school years (e.g., van den Ham & Heinze, 2018).

In a meta-study by the National Research Council (2004) in the US context, 698 studies on the effectiveness of altogether 19 US curriculum resources were evaluated. The commission summarized that only 63 of the studies were comparative studies that somehow measured the effect of the curriculum resources on students’ outcomes and were at least regarded as methodologically adequate. The lack of methodological quality was one of the reasons that led the committee to question the degree of certainty to which the curricular effectiveness of an individual curriculum resource could be determined.

Another issue in this context is that measuring effectiveness is influenced by the used measures and units of analysis (National Research Council, 2004; Törnroos, 2005). Therefore, the results of comparative studies are biased by the relation between the test items that measure students’ achievement and item-specific opportunities to learn that had been provided by the curriculum resources used. Furthermore, the results of comparative studies provide evidence only for the effects of whole curriculum resource designs together with their implementation in classrooms on student achievement, and thus give indications of overall curriculum resource quality. Studies investigating differential effects of specific design principles or content organizations are rare. Therefore, van den Ham and Heinze (2018) call for differential studies that unravel the mechanisms causing these textbook effects. Sievert et al. (2019) tackled this issue and investigated textbook effects on students’ adaptive expertise in strategy use in multi-digit addition and subtraction problems in the primary grades. They developed a theory-based model for the evaluation of mathematics textbook quality in terms of adaptive expertise. Their study shows a substantial effect of the textbook quality on students' adaptive expertise in multi-digit addition and subtraction. In this special issue, Sievert et al. (2021) deepen the understanding of the effect of textbook quality on students’ achievement by focusing on a different content area. They examined the effect of textbooks on students’ learning of quantitative comparisons by first, analyzing four German textbooks for Grade 1 and second, by conducting a secondary analysis of a dataset based on 1,513 students from 84 classes using one of the four textbooks. The results show that there is a significant relation between the quality of textbooks and student achievement in the topic concerned.

Closely related to the issue of effects of curriculum resources on student achievement, is how these resources influence students’ conceptual understanding (e.g., O'Keeffe & O'Donoghue, 2011). However, conceptual understanding is methodologically much more difficult to grasp. Furthermore, the difference between the instruments measuring achievement or conceptual understanding in the quantitative paradigm is in the end not clearly delineated. Therefore, we subsume these studies under the larger body of evaluation studies of curriculum resources.

In summary, this body of evaluation studies suggests that change can be mediated through curriculum resources. However, the positive effect of innovative and reform curriculum resources that is reported in studies needs to be questioned in many cases due to methodological issues. Therefore, there is apparently little evidence that innovative and reform curriculum resources have positive effects on students’ achievement. As opposed to studies on teachers’ use of curriculum resources that are mainly grounded in the qualitative paradigm and have the aim of understanding the particular mechanisms of the participatory relationship between teachers and resources, studies on effects of curriculum resources on students are predominantly grounded in the quantitative paradigm. These studies are hardly capable of unveiling the mechanisms in the student-resource relationship. Even if a positive effect of reform curricula on students’ achievement and conceptual understanding can be determined, it is not clear which design principles in particular account for these effects. There is a need for methodologically well-grounded comparative studies, which also include differentiated measures for the quality of curriculum resources and also consider the context of learning. First steps in this direction have been taken by Remillard et al. (2014) and Sievert et al., (2019, 2021). Additionally, qualitative studies of how design features of curriculum resources affect the participatory relationship between students and the resources could provide a deeper insight into the mechanisms that provoke conceptual development. In a qualitative analysis of two cases, Rezat’s (2021, this special issue) study takes a first step in this direction and provides insights into how automated feedback from a digital textbook can influence students’ conceptual development in desired and undesired ways. His findings support the requirement of developing curriculum resources based on design-based research to achieve a closer relation of the desired and actual effects on students’ achievement and conceptual understanding.

5.2.2 Curriculum resources as instruments to change students’ beliefs, identities and levels of participation

Few studies have investigated the effect of curriculum resources on students’ other characteristics such as attitudes, beliefs, perceptions about mathematics and about learning mathematics. Moyer et al. (2018) investigated effects of a standard-based reform curriculum that took a functional approach to the teaching of algebra and supported inquiry-based learning compared to four traditional curriculum resources on 12th grade students’ attitudes towards mathematics. They distinguished between three dimensions of attitude: (1) emotional disposition (appreciation or distaste for mathematics as well as positive and negative feelings related to mathematics), (2) perceived competence (ability in mathematics in general and in algebra in particular), and (3) vision (beliefs about what defines mathematics and algebra, beliefs about how mathematics is best learned, reliance on oneself, on peers and teachers in learning mathematics, preferences for modes of instruction). They found that students’ attitude profiles in the three dimensions differed significantly between the reform- and non-reform-curriculum student groups.

Due to the constantly growing availability of Open Educational Resources (OERs), their effect on students’ attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of mathematics and learning mathematics is receiving growing attention. Kersey (2019) investigated student attitudes and perceptions on learning and using OER in college calculus with 103 students in an experimental study. He found that the OER group viewed OER materials as more effective than the control group using traditional resources. Furthermore, learning from textbooks was ranked as the least effective learning style by all students.

Very little research has been carried out related to the effect of curriculum resources on students’ identity and participation. As opposed to the studies related to students’ attitudes and beliefs, the few studies in this area are qualitative and exploratory in nature. Taking the potential of textbooks to construct and convey social norms (e.g., Dowling, 1996, 1998; Rezat & Sträßer, 2012) as a starting point, Macintyre and Hamilton (2010) aimed to find out how textbooks may contribute to patterns of inclusion and exclusion in mathematics education. Based on an analysis of Scottish secondary textbooks, they carried out a qualitative analysis of group discussions with four focus groups from two schools with 12 students in each group, in which participants discussed the key findings from the textbook analysis in terms of the vision of mathematics (functional vs. abstract), layout and presentation, stereotypes and identities, and other identity criteria. The findings indicated that “learners did not see themselves as adequately represented, whether through the selection of appropriate personal names, interests or preferred/intended occupations” (Macintyre & Hamilton, 2010, p. 19). This was especially relevant for those learners who expressed higher respected career aspirations (such as accountant, advocate, dentist, doctor, fund manager, lawyer, police officer, teacher, veterinary medicine).

Similarly, Ewing (2006) conducted a qualitative interview study with 43 students in order to demonstrate how shaping of an identity of participation in mathematics is influenced by the practice of using textbooks in classrooms. She found out that students with learning difficulties who were not successful in learning mathematics from textbooks without support from the teacher, chose not to participate in their learning.

These findings indicate that students’ beliefs and attitudes towards mathematics as well as their identities and levels of participation are influenced by both the content and its presentation in curriculum resources, and the ways they are used for the learning of mathematics. Therefore, curriculum resources and their use may also have the potential to change students’ beliefs and attitudes towards mathematics as well as their identities and levels of participation. In terms of content, there are indications that the content of curriculum resources needs to take more account of students’ interests and career aspirations. As important as the content of curriculum resources is the way they are used in the classroom. Learners with learning difficulties cannot be left alone with learning from the curriculum resource but need support in their transition from marginality to full legitimate participation in mathematics.

6 Conclusions

From the reviewed literature, it became clear that curriculum resources take an intermediate position aligned with a mediatory role at different levels within the educational system. On a macro-level, they are expected to mediate policy into practice (Valverde et al., 2002), i.e., to mediate between educational goals and prescribed curriculum content and classroom activity. On a micro-level, they serve as a tool or artefact that mediates among teachers, students, and mathematics (e.g., Rezat & Sträßer, 2012), and “re-source” teachers’ and students’ mathematical practice (Adler, 2000, p. 207). They are often theorized as artefacts within socio-cultural theories, as potentially implemented curriculum in curriculum theory, and as an intermediate variable in more causal research models. Due to their intermediate position and their mediatory role, curriculum resources have the potential to mediate between reform ideas and their users (e.g., teachers, students, parents) by influencing their practice. Growing evidence supports that this mediation also results in different teaching practices and affects students’ achievement. Sievert et al. further support this evidence with their paper in this special issue. How the potential to mediate change is unfolded is influenced by the curriculum resources, by characteristics of their users, and shaped by the participatory relationship between users and the resources. Besides these characteristics of the users and the curriculum resources, the participatory relationship is also shaped by socio-cultural practices and the transparency of the curriculum resources in these practices.

So far, in the case of teachers, research has contributed to a better understanding of this participatory relationship based on many case studies. The papers by Fan et al., Glasnović Gracin and Jukić Matić, Olsher and Cooper, Remillard et al., and Shinno and Mizoguchi in this special issue, add to this body of knowledge and further deepen this understanding. The papers by Adler, Cai and Hwang, and Gueudet et al. in this special issue show a tendency to support the enactment of change through curriculum resources through additional resources such as ideational or meta-resources that make the socio-cultural practices more transparent and accessible.

There is a plethora of research on single elements such as tasks, worked examples, or diagrams incorporated in the structure of curriculum resources. The papers by Confrey and Shah, Edson and Difanis Phillips, Mesa et al., Prediger et al., and Rezat contribute to this body of knowledge by analysing the interactions of users with different innovative features of paper and digital curriculum resources and how these affect teaching and learning of mathematics and the enactment of reform. While most of these studies focus on the teacher and his/her participatory relationship with the curriculum resources, Rezat’s paper further adds to qualitative studies that unveil the mechanisms in the participatory relationship of students with curriculum resources.

However, there still is a dearth of research that investigates how the individual elements and features function in the context of the overall structure of the curriculum resource, and how they contribute to convey the overall pedagogical model. The paper by Choppin et al. presents a first step in this direction. The authors show how teachers are influenced by overall features of the materials that are related to the pedagogical model.

A possible consequence of the research summarized in this survey is that the idea of designing resources that mediate reform ideas through their overall design to be implemented as a whole, may not be the goal to be achieved. Curriculum resources that already incorporate the possibility of orchestration and implementation into a resource system in their design seem to adjust more to the needs of their users. This development might be sustained by the increasing role of digital curriculum resources. The notion of ‘quality’ of curriculum resources is likely to change, as any envisaged learning progression does not remain static (as in analogue curriculum resources), but traversable in individual ways, and connections can be made to other (digital) curriculum resources. This flexibility is likely to add a ‘dynamic’ quality to e-textbooks. In this context, Pepin in her paper in this special issue introduces the notion of connectivity as a crucial principle for students to co-design (e.g., with their teachers and peers) coherent learning trajectories, when using a number of digital curriculum resources.

The ongoing shift from paper to digital curriculum resources might also yield changes in their design and use. Whereas the design of curriculum resources in many countries around the world used to be ‘dominated’ by curriculum developers (e.g., ministerial representatives, inspectors), now classroom teachers are often involved in the co-design of curriculum resources. Students might work more independently with the resources and also have access to a greater variety of digital resources on the web with varying quality. They might select and use other digital resources in addition to curriculum resources provided by the teacher. In that sense, students can be regarded as co-designers of the enacted curriculum and thus as independent partners in the teaching–learning activity as depicted by the didactical tetrahedron in Fig. 1. This role of students implies that students as users and as the addressee of the presentation of the mathematical content have to become more critical, and knowledgeable about assessing curriculum resources for their beneficial learning and the development of their curriculum trajectories (e.g., in higher education). A better understanding of students’ use of and interaction with curriculum resources, their learning experiences with such resourced environments, and their educational benefit, is necessary. At the same time, students’ growing ownership of selecting their learning resources implies that reform can also go through ‘unofficial’ materials that students find on the web and use for their learning (e.g., Khan Academy; video clips for test preparation). Therefore, these ‘unofficial’ resources also have to be considered in mediating change of students’ encounter with and learning of mathematics. Moreover, this ownership points to the increased need for further research that investigates teachers’ and students’ resource systems (e.g., Ruthven, 2019), rather than the single resource items. There are also other tools (e.g., digital platforms) available that may support teachers in their efforts to enact curriculum reforms and facilitate students’ learning of mathematics. Indeed, this aspect shifts the attention away from the design of curriculum resources as a comprehensive and coherent whole, to the design of elements or modules that are used, recombined or omitted in the course of teachers’ and students’ co-design of the enacted curriculum.

Notes

UCSMP: University of Chicago School Mathematics Project.

RME: Realistic Mathematics Education.

Now Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study.

References

Adler, J. (2000). Conceptualizing resources as a theme for teacher education. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 3(3), 205–224.

Adler, J. (2021). Levering change: The contributory role of a mathematics teaching framework. ZDM Mathematics Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-021-01273-y

Anastasakis, M., Robinson, C. L., & Lerman, S. (2017). Links between students’ goals and their choice of educational resources in undergraduate mathematics. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 36(2), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrx003

Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1996). Reform by the book: What is—or might be? The role of curriculum materials in teacher learning and instructional reform? Educational Researcher, 25(9), 6–14.

Bergsten, C., & Frejd, P. (2019). Preparing pre-service mathematics teachers for STEM education: An analysis of lesson proposals. ZDM Mathematics Education, 51(6), 941–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-019-01071-7

Bokhove, C. (2017). Using technology for digital mathematics textbooks: More than the sum of the parts. International Journal for Technology in Mathematics Education, 24(3), 107–114.

Brantlinger, A. (2011). Rethinking critical mathematics: A comparative analysis of critical, reform, and traditional geometry instructional texts. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 78(3), 395–411.

Brown, M. W. (2002). Teaching by design: Understanding the intersection between teacher practice and the design of curricular innovations. Northwestern University.

Brown, M. W. (2009). The teacher-tool relationship: Theorizing the design and use of curriculum resources. In J. T. Remillard, B. A. Herbel-Eisenmann, & G. M. Lloyd (Eds.), Mathematics teachers at work: Connecting curriculum resources and classroom instruction (pp. 17–36). Routledge.

Burkhardt, H., & Schoenfeld, A. (2020). Not just “implementation”: The synergy of research and practice in an engineering research approach to educational design and development. ZDM Mathematics Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-020-01208-z

Cai, J., & Howson, G. (2013). Toward an international mathematics curriculum. In M. A. Clements, A. J. Bishop, C. Keitel, J. Kilpatrick, & F. K. S. Leung (Eds.), Third international handbook of mathematics education (pp. 949–974). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4684-2_29

Cai, J., & Hwang, S. (2021). Teachers as redesigners of curriculum to teach mathematics through problem posing: Conceptualization and initial findings of a problem-posing project. ZDM Mathematics Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-021-01252-3

Choppin, J., Davis, J., Roth McDuffie, A., & Drake, C. (2021). Influence of features of curriculum materials on the planned curriculum. ZDM Mathematics Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-021-01305-7

Choppin, J., & Borys, Z. (2017). Trends in the design, development, and use of digital curriculum materials. ZDM Mathematics Education, 49(5), 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0860-x