Abstract

This study is a critical review of public intervention and its management of change with digitalization, applied to Spanish tourism services, as ones of the largest case and most required of attention into the European Union. In comparison with other mainstream papers, this heterodox review is based on the combination of Austrian Economics and Neo-Institutional approaches (Cornucopists), with their common theoretical and methodological frameworks. Thus, it is possible to analyze failures and paradoxes in the public intervention, especially with post-COVID recovery policies. The case of the Spanish tourism sector highlights the effect of double bureaucracy, from European institutions and the Spanish Government, affecting its competitiveness and revealing the confirmation of heterodox theorems. Faced with mainstream public intervention guidelines, which usually involve expansive spending and more debt (and New-Malthusian measures), a heterodox mainline solution is offered here, based on the revival of the original sustainability principle, the readjustment effect and the promotion of geek'n'talent education, to facilitate the transition to the Knowledge Economy, where the tourism sector is capable of offering personalized travel experiences due to digitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

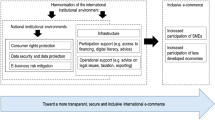

Usually, mainstream economic papers, according to the Neoclassical Synthesis (NS), are focused on applied economics and follow the methodology of natural sciences and engineering (hypothesis and confirmation with data). This study is a heterodox review (based on principles and propositions with illustrative cases) on Political Economy (with special attention to Public Management and Public Economics, Ferlie 2017), to rethink the current economic theory, utilizing evidence from Economic Policy, to illustrate the cases. This research is a revival of the Methodenstreit or methodological dispute in Economics (Menger 1883; Sánchez-Bayón et al 2023). The current inquiry is not econometric (with ultra-empiricism -Blaug, 1968- and mathiness -Romer 2015), but is a review based on critical (hermeneutical thought) and comparative (diachronic-synchronous and marginal analysis) approaches linked to the social sciences and their methodologies (Sánchez-Bayón et al 2023). So, the current critical review is based on the recognition and management of social change in process and its real adaptation (with a paradigm switch, Sánchez-Bayón, 2020a), while paying attention to the resistance to changes (i.e., post-Keynesians with de-growth project, Cosme et al 2017; Kallis et al 2018). This review is proposed according to mainline heterodox approaches (Alonso-Neira et al 2023; Sánchez-Bayón, 2022a, b, c; see Fig. 1), like Austrian Economics-AE (Rothbard 1995; Huerta de Soto 2000, 2009), New-Institutional Approaches-NIA of New Political Economy-NPE (i.e. Law & Economics-L&E, Public Choice-PCh, Constitutional Economics-CE, Sociological Institutionalism, Possibilism, Anderson 1986; Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Hirschman 1970, 1993; Posner 1973) or Cultural Economics (i.e. Behavioral Economics, Evolutionary Economics, Diamond et al. 2012; Thaler 2016). In this review, the main change factors are globalization and digitalization (Kraus et al. 2021, 2022, 2023; Sánchez-Bayón 2021a; Song et al. 2022): with the transition between social realities (i.e., from Atlantic Coast to Trans-Pacific Area; from materialistic to digital markets) and new industrial and technological revolutions (i.e., from 4th industrial revolution with internet of things-IoT—Schwab 2016—to 5th industrial with wellbeing economics-WBE—Sánchez-Bayón et al. 2021; Sarfraz et al. 2021); also, with new agents, stages and rules of Geoeconomy (Clayton et al. 2023).

Relations among economic schools (Sánchez-Bayón, 2022c)

The purpose of this review is to criticize the mainstream public management and its intervention into the tourism sector and its services, especially with post-COVID recovery policies (Bagus et al 2021, 2022; Huerta de Soto et al. 2021) showing displacement effect and ratchet effect (Peacock and Wiseman 1979; Jaén-García 2021). The goals are: (1) To explain the failures and paradoxes in the tourism sector caused by the public management due to its resistance to change and current mainstream solutions—expansive spending, more debt, and second round effects such as zombie companies (Ren et al. 2023; Zhao et al. 2021, 2023); (2) To review the economic principle of (original) sustainability, entrepreneurship and economic calculation or Mises´ theorem (Coase 1937; Mises 1949; Kirzner 1973, 1987); (3) To offer an alternative solution to mainline proposal (Boettke et al. 2016), based on the Ricardo effect or readjustment effect (Hayek 1935, 1939; Arnedo et al. 2021) and developing geek'n'talent education (Sánchez-Bayón and Trincado 2020, 2021); (4) To apply this review to the case of the Spanish tourism services, as an illustration (not confirmation, Alonso et al. 2023).

2 Literature review

A current robust literature review on tourism business digitalization is offered by Felicetti et al. (2023), Calderon-Monge and Ribeiro-Soriano (2023a) and Ribeiro-Navarrete et al. (2023); and for literature review on tourism management innovation are suggested Cem et al. (2019), Shin and Perdue (2022), Lin et al. (2023), Wegner et al. (2023) and Zuñiga-Collazos et al. (2023). All these reviews have been carried out in accordance with the mainstream (within the framework of the Neoclassical Synthesis-NS), but this review goes further, by considering itself in mainline terms of the heterodox synthesis (Sánchez-Bayón 2022a, 2022b). This is a mainline mix, between AE and NIA, as these economic schools coincide in the principle of realism (without wishful thinking) and the methodological individualism and its (re)composition for complex phenomena explanation (Hayek 1988—beyond NS´ methodological individualism, which not analyzed in deep into the State or the firm). These principles handle the changing social reality while not confirming, but discovering changes in the process (Feyerabend 1975; Huerta de Soto 2009).

This review is framed in a socioeconomic research agenda (Lakatos 1978): an inquire into the digitalization and its changes on labor relations and business culture (Sánchez-Bayón 2020a, 2020b, 2021). In this case, the attention is focused in the tourism services into the European Union-EU (Figini and Patuelli 2022; González et al. 2021). This study concentrates on the EU tourism paradox, specifically in Spain, where tourism is the main industry. However, under the public management, the tourism industry is becoming less competitive, with an increased number of zombie companies (Ren et al. 2023; Zhao et al. 2021, 2023); to fix this, it is required a readjustment effect based on digitalization and its education on geek'n'talent (Sánchez-Bayón and Cerdá 2023; Arnedo et al. 2021; García-Vaquero et al. 2021).

Currently, there are two opposing economic views to analyze the social changes: the new-Malthusians or de-growth defenders (socialist economic schools and new & post-Keynesians; see Fig. 1) and the Cornucopists or developers (AE, NIA, etc.). The new-Malthusians have a negative vision toward change, such as digitalization, while at the same time they defend a normative economy based on their value judgments to transform the reality. On the other hand, the Cornucopists or developers are in favor of change and technology (for abundance), because they perceive an opportunity for growth and improvement, according to a positive economic approach (not normative) that helps to explain complex social phenomena.

With this background, it is possible to review the changes, adaptations, and resistance to these changes. The current mainstream (new & post-Keynesians, see Fig. 1), it supports New-Malthusians theories (in opposition to free change and in favor of centralized control): new-Luddites (Obanor 2021); technological unemployment (Keynes 1930, 1937-criticized by Hazlitt 1946); great decoupling & digital paradox of employment (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014). Part of the resistance to change is due to the high cost of learning and adapting process; also, the fear to loss benefits in the current model (NS and Welfare State Economy-WSE). However, changes have already occurred in social reality, so the longer it takes to respond, the greater cost will be the adaptive process.

NS and WSE were designed for the industrial capitalism (from 1880 to 1960, characterized with materialistic view, massive production and the presumption of homogeneous and re-generated production factors, full employment, etc.—also it is based in few fallacies, Weingast 2016). Currently, there is a transition to Wellbeing Economics-WBE with the Digital Economy-DE through the emergence of talent capitalism-TC (main productive factor is digital and practical knowledge or geek´n´talent, Sánchez-Bayón 2020a, 2020b, 2021a; Sánchez-Bayón and Trincado 2021). TC is the new step of capitalism (beyond the developed capitalism based on massive services, 1970´s). TC is producing changes in business culture and in jobs and labor relations (into digital economy), and coining few new kind of dynamic concepts: emprosumer (entrepreneur + producer + consumer), knowmands (knowledge + nomads), mindfacture (mind + facture/production), etc. (Sánchez-Bayón 2020a, 2020b, 2021b; Sánchez-Bayón and Trincado 2020). This type of new capitalism emphasizes the digital labor relations, which means that technology will not take away jobs, but will facilitate new ones, so a good relationship with technology being the key to offering personalized experiences.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to respond to the research question: Do the various waves of digital transition mean job destruction and technological unemployment in WSE or, on the contrary, do they serve as a stimulus for techno-digital intensification and talent development that enables the transition to talent capitalism? Data of international forums and organizations (i.e., WEF, OECD, ILO) confirm the coexistence of both scenarios (destruction of obsolete jobs and emergence of new carriers).

Traditional jobs with low qualifications and remuneration become obsolete while others with high qualifications and better working conditions are generated. The point is to recognize that the digital transformation of the economy involves job redesign, which in turn requires profound educational transformations (upskilling and re-killing, like geek'n'talent). This approach allows to then addressing the failures and paradoxes of the Spanish tourism sector.

3 Results and discussion

Globalization and digitalization blend has produced transformative changes (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014; Sánchez-Bayón 2021a; Suresh 2010), which is typical of the capitalism´s process (Huerta de Soto 2009). This blend affects labor relations and business culture; also it is part of a biggest change or revolution (industrial, technological and energy revolution: from 4 to 5th revolution, Sarfraz et al 2021). Among the most relevant changes experienced see the following table (Table 1).

All those changes have transformed the rules of the game and its management (UN 2012; OECD 2012): from the type of economic agents and their role in the economy (emerging new and dynamic combinations, since there are no longer rigid and immutable separations, i.e. emprosumer), through the renewal of economic activities and sectors (i.e. consumer-to-consumer relations through social networks), where the physical world coexists with the virtual one, operating in a “glocal” way (global + local); up to the rules of distribution and the financial instruments (i.e. digital currencies). Robinson (1962) advanced the change of values (Suresh 2010; Valero et al. 2018); Galbraith (1958) and Keynes (1936) warned of the difficulty of changing values due to the burden of previous thinkers and their economic postulates.

Consequently, a paradigmatic review is urgently needed to appraise the economy as a whole and, above all, its growth and development model (UN-SG 2012; UN-SNDP 2013; UN-UNDP 2013; UN-GA 2015; OECD 2019; EU-Consillium 2019a, b; plus Florida 2010; Sánchez-Bayón 2017; Valero et al. 2018; Llena-Nozal et al. 2019; Schwab and Malleret 2019). This revision has intensified since the Great Recession of 2008, and has achieved a change of system from industrial and developed capitalism towards capitalism of talent (i.e. knowmads, riders, and other working modalities of the so-called gig economy). Not pursuing the paradigmatic transition—due to resistance to change—implies a growing gap between the available academic knowledge and the progress of the underlying reality. However, this study and its thesis start from a context of focus on the WBE model (DE next stage, Garcia-Vaquero et al. 2021; Sánchez-Bayón and García-Ramos 2021), analyzing how the digital transition has affected the development of labor relations. Thus, the study refutes the stance of resistance to change based on the risk of technological unemployment (Keynes 1933, 1936 and 1937) and traditional labor protectionism (Keynes 1930). Within the digital transition, it is not a matter of the competition of man vs. machine (Luddites and socialists of 1st International), or even a question of humans following the pace with technology, but is an issue of human labor being forced to adapt to the technological changes (Keynesians and socialists of the Second International). Each position that is destroyed by the technological growth, at least four types of related positions are generated: the designer, the manufacturer, the user and the reviewer or maintainer. Therefore, Human labor will be forced to adapt to technological changes.

Some authors, such as Gómez (2019), consider that there will be no work scarcity in countries with a capital-intensive economy (more robots and artificial intelligence, Bordot 2022). Therefore, greater preparation will be necessary with educational initiatives through technical specialization and related talent development (according to the survey carried out on 5500 employees and executives in 27 countries realized by Oxford Economics and SAP in their 2020 workforce).

Right before COVID-19, there have never been so many people working in the US (according to the US Labor Secretary and US Census Bureau in 2018), and almost all over the Western World. The most digitized countries with the highest robotic density had had lower unemployment rates. Moreover, they did not fill the new digital vacancies due to lack of talent; hence, the transition from trade wars to talent wars has not been achieved. The social employment contract had to be revised, since the life expectancy of the companies had fallen to 15 years; therefore, they cannot offer contracts for the entire working career of a person (being 30 years or even more with the ageing of the world population). Between the COVID-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine, the trend has recovered, accentuating the differences between the digitized countries and those that are not, drawing a K-shaped recovery model: in the ascending vector are the digitized and observers of WBE, while in the descending one, there are less digitized and obstinate in Welfare State Economy-WSE or Economics of Welfare (Pigou 1920).

Faced with future crises, such as possible job destruction and mass unemployment, empirical evidence seems to indicate that a transformation similar to that of past transitions is currently taking place again. An example is the one that occurred in the 1880s, with the shift from commercial to industrial capitalism, making half of the jobs disappear in the primary sector (livestock and agriculture), but generating more than double jobs in industry and services. In this sense, it is proposed as a complementary objective of this review: the exposition and explanation of the revised Ricardo Effect -or readjustment- which is raised here (in addition to enunciating paradoxes such as economic-cybernetic or happiness, to be developed in other works) to facilitate in the end an overview of the theory of capital, economic cycles, the structure of production, and the evolution of social institutions (Menger 1871; Hayek 1952).

A synthesis of Ricardo or readjustment effect is offered now: its name, Ricardo effect, according to AE, was established by Hayek (1935 and 1939) in honor of the classical economist David Ricardo and his theory of savings-wage relations (Ricardo 1817). This proposal refers to the microeconomic rationale according to which variations in savings have an impact on the level of real wages. Hayek assessed its consequences, such as the possible replacement by capital goods. From there, he connected this effect with the theory of capital and business cycles, observing that the same thing happened if there was a credit expansion. Thus, using his triangle of the productive process (see Fig. 2), Hayek incorporated the Ricardo effect to explain the distortions in the process and the productive structure, due to wage variations, especially those not based on the increase in productivity but by the effect of savings and investments, and the worst, by credit expansions without support in savings (then with distortion in prices and therefore in economic activity). This proposal was called Ricardo or concertina effect controversy (Wilson 1940; Kaldor 1942), with debate revival (Moss and Vaughn 1986; Steele 1988; Birner 1999; Garrison 2001. Gerhke 2003; Huerta de Soto 2006, 2009; Klausinger 2012; Ruys 2017). This revival for digital economy is so-called readjustment effect, because it pays attention to reallocation of human talent according to the geek skills (García-Vaquero et al. 2021; Sánchez-Bayón et al. 2021). When wages are artificially raised in the phases closest to consumption (by credit expansion and inflation, Alonso-Neira et al. 2023; Sánchez-Bayón and Castro 2022), this will cause the replacement of workers (employees) by capital goods (i.e. robots, programs). This freeing up of the labor factor will be relocated to phases of production further away providing more value due to the development of talent, and therefore, the employees will earn a higher salary and experience better working conditions, while achieving greater satisfaction. The following figure illustrates the production process and structure according to the AE (see Fig. 2).

The originality of this review is the explanation offered from Ricardo or concertina effect to readjustment effect revival and its illustration with the case of Spanish tourism sector. Some clarification on this effect is provided in the table below (Table 2).

The Ricardian theory is intended for commercial capitalism, not industrial, which arrived in the 1880s with the second industrial and technological revolutions. The theory is based on an objective value theory (surpassed with the marginality revolution of Jevons–Walras–Menger), which considered costs, and therefore wages, as a determinant in price fixing. Such an approach is not valid in DE and, even less, in WBE and talent capitalism. This approach will arrive with the 5th industrial and technological revolutions planned for H2030.

Readjustment effect is connected also with other economic principles and propositions, such as the Brunel effect, Hicks compensation variation, etc. Nonetheless, in order to make this work combination, it is essential that the Public Sector will not interfere, except to facilitate the educational conditions of technical transformation, thus avoiding fiscal distortions.

There are three paradoxes to discuss regarding the application of the readjustment effect: The Economic-Cybernetic Paradox, The Paradox of Happiness, and The Jevons Paradox (see Table 3).

These three paradoxes are applicable to the tourism sector, as long as it ceases to be produced according to the parameters of industrial capitalism, WSE and NS (Keen 2020). Massive, standardized and intensive services are not required in low or medium skilled jobs, which are the most common in the tourism industry. Facing the relevance of digital transition, the tourism industry will need to move towards the orange economy of the emotion industry, with higher focus in tailor-made /personalized experiences (García et al. 2021a, b).

In addition to these paradoxes is an analysis of the principle of sustainability and business risk (focused on the tourism sector, where the average life of the companies is reducing). The current mainstream, new & post-Keynesian, maintains that there are market failures, which justify priority public intervention (Stiglitz and Rosengard 2015), through credit expansion and greater debt, stimulating aggregate demand and its consumption (Belfiore 2004). The principle of sustainability has been reinterpreted, and includes issues of interest to stakeholders, such as climate change and gender, while being (Ferguson and Moreno 2014) intensified with the COVID-19 crisis (Prause 2021; Yanuar 2021) emphasizing the intervention measures including credit expansions, greater indebtedness for aid and transfers (with clientelism, Buchanan and Tullock 1962). However, these mainstream approaches have given rise to the effect of zombie companies: companies that are subsidized, that do not earn income or the little they earn goes to pay costs and debt (Ren et al. 2023; Zhao et al. 2021, 2023). In reality, the phenomenon of zombie companies after the Great Recession of 2008 (Golub and Lane 2015; Kuifu and Ning 2016; Zhou et al. 2018), and the solutions of the new mainstream leadership by new & post-Keynesians, with the measures already raised. As a mainline alternative, a review of the principle of sustainability and business risk based on the combination of AE (i.e., entrepreneurship, economic calculation) and NIE (i.e. theory of the firm) offers that the original sustainability is that related to continuity of the company throughout time, which requires its productivity the Ricardo effect or readjustment (Hayek 1935, 1939; Arnedo et al 2021) and developing geek'n'talent education (Sánchez-Bayón and Trincado 2020, 2021).

4 Case study: tourism services into European Union and Spain

There is a certain paradox about the tourism sector within the European Union: despite contributing more than 10% of the European GDP and employment rate (TRAN Committee 2019; European Parliament 2022, 2023), no special attention was paid to it until the new legal framework with Lisbon Treaty in 2009, and it still has not its own budget item. The dilemma for tourism sector is whether more attention from the European Union (EU) would mean an improvement (growing its weight in the Single market) or a worse situation (according to Mises´ theorem and the risk aleterd: entrepreneurship loss, impossibility of economic calculation and the distortion of interventionism). Furthermore, when the EU began to consider tourism as a theme on the strategic agenda for their multiannual financial periods (current is 2021–27, affected by Green Deal, Trincado et al. 2021), the tourism results have decreased: why? EU and Governments defend that is the second-round effect of several consecutive crises (i.e. COVID-19, Ukraine war, Middle East conflicts). This consideration cannot be sustained, since other non-EU countries, such as Iceland and Norway have increased their results in tourism during the same period and with similar conditions. Even into the Eurozone, there are countries with great results, like Ireland, Estonia or Croatia; also into the EU at large (not-Eurozone members), Hungary or Czech Republic, they have doing well in tourism results. What do they all have in common? The key of their success is the digital transition and the observance of WBE model.

In the Spanish case, the tourism paradox is more intense: in 2018, tourism generated 147,946 million euros, representing 12.3% of Spanish GDP, and produced 2.62 million jobs, which means 12.7% of total employment (INE 2019—revised on 2020; Fig. 3). In 2020, Spanish tourism sector only generated 61,406 million euros, that is 5.5% of GDP and 2.6 millions of subsidized jobs (INE 2020; see Fig. 3). How can the tourism sector has been practically closed (during the confinements and restricted later) and, at the same time, it has maintained almost the same level of employment? The answer may be it is related with the EU's Next Gen funds (NGF). Currently, despite the Spanish tourism sector has being a priority objective of NGF (for its digitalization), however only 10% reached the sector and in the form of credits (i.e. Instituto de Crédito Oficial-ICO credits), to continue paying the Administrations (even during the confinements and without economic activity –this is important to understand the mentioned phenomenon of zombie companies).

In the previous figure, there is a comparison of data pre & post-COVID-19, to illustrate the rebound effect (illusion of recovery without reaching pre-crisis level). According to the public management carried out, tourism sector reduced its contribution to GDP by 60% (INE 2020), while jobs were maintained through subsidies, destroying more than half million self-employment and small businesses became zombie companies (earning only to pay the interest of their debt). The implementation of NGF has been a missed opportunity, as it has not been possible to execute even 50% of the available funds, lacking transparency in their distribution (European Commission 2022). The last initiative has been the program “Spain Tourism Experiences” (ruled in Ministerial Order of July 26, 2023), with more applications from public institutions than private business.

Before Lisbon Treaty (2009), tourism sector into the EU was supported by the European Regional Development Fund (European Commission 2014) to promote the competitiveness, sustainability, and quality of the sector at the regional and local levels. Later, tourism was included as a common policy, but there was not more integration because in that period it was the Common Agricultural Policy-CAP gate: CAP was the main common policy into the EU, but the World Trade Organization-WTO established a double penalty fees (to each country part of EU and the EU –after Lisbon Treaty the EU was a legal person, who signed international treaties), based on abusive practices such as subsidizing European farmers, with greater commercial barriers to producers from developing countries. Under the Green Deal, CAP was renamed and fragmented in a diversity of funds related with ecological issues and the promotion of rural areas (Trincado et al 2021), and it worked to stop the international sanctions –but there was more red-tape for the European farmers-. For this reason, there was no intention to replay the CAP and agriculture sector experience in other economic sectors. The issue changed with the aforementioned crises and the need to reactivate the tourism sector after the confinements and later mobility restrictions. The design of NGF was implemented for the recovery of the most confined sectors, including tourism, due to the damage caused by the crises. Also, the design of NGF pretended to improve the digitalization and the promotion of green jobs (García-Vaquero et al. 2021). In this way, the conversion model initially planned for the energy sector was extended to other sectors (Arnedo et al. 2021). Nevertheless, the expected results have not been achieved, at least in Spain, due to the lack of transparency in the management of funds and the scarce digitalization, limited to the compatibility of teleworking and furloughs. The opportunity to undertake the readjustment has not been faced in crucial actions including talent development or offering training in technical subjects, which would allow workers to look for job opportunities in higher stages and with better working conditions. On the contrary, the concept of “social shield” (Government of Spain 2021) has been coined, meaning workers are expecting to recover their old, already out of date jobs, due to lack of digitalization, instead of favoring a readjustment effect.

Back within the EU, despite the funds allocated for the recovery of the tourism sector, its recovery to pre-COVID-19 levels is not expected until 2023 (European Parliament 2022, 2023). 30 million jobs were lost, half of which were recovered due to digitalization and hybrid systems (combination of face-to-face and virtual work). The resolutions and communications of the European institutions during the COVID-19 crisis were mainly oriented to health concerns; therefore, it caused not only the aggravation of the effects of the pandemic but its condition of syndemic (Sánchez-Bayón 2021b, 2022). Applying the theoretical framework of AE & NIA-NEP, Mises' theorem (on entrepreneurship & economic calculation—for this, it is impossible the socialism- and Buchanan-Tullock corollaries—on unfinished agenda, rent seekers, clientelism, etc.—are confirmed: centralized management of the COVID-19 crisis by EU has been less efficient than the decentralized one, as has happened in Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand, according to ICT & LKT. The route of mass confinements and the bureaucratization of purchases of sanitary materials and vaccinations were not chosen in those countries where personalized digital response was preferred (due to tracking apps, preferential vaccinations, and social media influencers, Ata et al. 2022).

In summary, in order to recover the pre-pandemic levels of the EU tourism sector and potentially exceed them, it is fundamental to stop spending recovery funds just as simple subventions (as fiscal transfers and not multiannual investments). In the same way, those funds will act as investments oriented to increase training in digital and technical skills, and global talent management initiatives based in re-skilling and up-skilling in the tourism sector.

5 Conclusions

The review offered here, it supposes a multidimensional critic: (a) to the mainstream of Public Management and Public Economics, because the solutions are so bureaucratic and slow for the digital transition (which requires agile answers), and very expensive and inefficient, with the preference for spending and credit expansion; (b) to the WSE model and its NS, based on materialist and massive production, because both are more mathematical than realistic expressions, with many assumptions and far from the changes happened; (c) to the EU, for ceasing to be an international organization to promote economic freedom and a common market, to become a supra-state bureaucracy, which seeks coercive centralized planning, with hyperregulation, quota control and professional and business restrictions; (d) the paradoxical treatment of tourism in the EU, because despite its economic importance, it has gone from minimal attention to its treatment as any common policy and now runs the risk of being subjected to the Green Deal and its centralized planning, violating the theorem by Mises; (e) to mainstream management from the EU, influenced by neo-Malthusian approaches, which put productive sectors at risk, in addition to establishing requirements for digitalization, which actually discourage or make it impossible, since the priority is economic degrowth.

This study has sought to clarify the importance of change management (without resistance and with the help of technology and knowledge—in Cornucopian way), especially in the current volatile era. This implies a paradigmatic revision, which in turn requires resorting to other visions, such as those offered by heterodox economic approaches and schools (which may become the mainstream in the future, if they prove their value). For this review, it has used the combination of contributions from AE & NIA-NEP (Cornucopians or developers, pro digitalization), in contrast with the current mainstream, under new & post-Keynesians views (new-Malthusians or degrowthers, in favor of public intervention). According to AE, DE involves a change in the structure and production process, requiring a readjustment effect, so the company culture and labor relations are efficiently redesigned. This implies facilitating that those rigid companies, with unskilled workers and monotonous jobs could be transformed into flexible companies with talented collaborators—those are the profiles required for the future of the tourism sector in the digital economy since its workers and professionals must be able to offer better and more personalized experiences. The achievement of this readjustment not only consolidates the WBE model and the transition to talent capitalism, but also gives rise to the so-called economic-cybernetic paradox: the more technology increases, the more human the economy and labor relations are required, provided that the principles of WBE are followed.

In the digitalization-work relationship, the possible destruction of employment and digital unemployment will be compensated with the adaptation of jobs and the appearance of new ones. For each type of job that becomes obsolete and disappears, four new jobs are generated: the designer of the technology, manufacturers, users, and technical supervisors. The readjustment effect facilitates this transition: from unskilled, easily replicated, and dependent workforce will be replaced by capital goods, being freed and urging a geek training or digital training of technological specialization, to discover their talent and apply them in DE. In this way, workers will become talented collaborators, in higher phases further away from production level, and in accordance with WBE, thus providing added value and in exchange receiving better salaries, working conditions, and intangible assets.

The necessary transformation of the European tourism sector, specifically the Spanish sector, concludes that central coactive planning, according to a strategic agenda and multiannual financial periods is not feasible. Also, this intervention is against to the Mises’ theorem and Buchanan-Tullock corollaries will be fulfilled (as is already the case with the CAP and the agricultural sector). For the tourism sector recovery, there is an urgent need for a readjustment that would enable workers and professionals to offer better and more personalized experiences (as a comparative advantage over other lower-priced tourism proposals). It is no longer only a question of quality but of continuous innovation. This requires geeky transformation and talent development (unlike the restrictions and dependencies of the Green Deal, according to the Mises and Buchanan-Tullock theorems). In addition to influencing economic systems and their location in the K model of post-COVID-19 recovery, achieving the readjustment effect is key to reactivating the tourism sector.

The Spanish tourism services are affected by the public management, as according to the Spanish Government, the tourism sector is the main sector, but from the 40,000 millions of euros executed from Next Gen EU, this sector only has received around 4000 million of euros, in credit lines by Spanish public finance institutions (i.e., ICO). Some other companies suffered the bail-out practice (i.e., SEPI). That is the reason because close to 10% of the tourism businesses are considered zombie companies. According to the heterodox solution that this paper offers, it is necessary to consider the readjustment effect, the review of (original) sustainable principle (and other economic principles), and the promotion of geek´n´talent education.

For future research lines, it is necessary to collect data to support this research, but there is a problem of compliance on the topic. The Spanish Government has not constituted an independent institution to receive and distribute the Next Gen EU funds: there is not enough transparency and accountability, nor do financial compliance institutions in Spain (i.e., Auditors Court, AIREF. OCEX) have the legal ability to act within this issue. Therefore, the next research will need to elaborate utilizing a private database.

References

Alonso-Neira MA, Sánchez-Bayón A, Castro-Oliva M (2023) An heterodox History of Spanish Economy into the Eurozone: Austrian School of Economics analysis of boom & bust. Forum Scientiae Oeconomia 11(2):9–41. https://doi.org/10.23762/FSO_VOL11_NO2_1

Anderson M (1986) The unfinished agenda: essays on the political economy of government policy in honour of Arthur Seldon. Institute of Economic Affairs, London

Arnedo E, Valero J, Sánchez-Bayón A (2021) Spanish tourist sector sustainability: recovery plan, green jobs and wellbeing opportunity. Sustainability 13(20):11447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011447

Ata S, Arslan HM, Baydaş A, Pazvant E (2022) The effect of social media influencers’ credibility on consumer’s purchase intentions through attitude toward advertisement. ESIC Market 53(1):e280–e280. https://doi.org/10.7200/esicm.53.280

Bagus P, Peña-Ramos J, Sánchez-Bayón A (2021) COVID-19 and the political economy of mass hysteria. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041376

Bagus P, Peña-Ramos J, Sánchez-Bayón A (2022) Capitalism, COVID-19 and lockdowns. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib BEER 31:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12431

Belfiore E (2004) Auditing culture: the subsidised cultural sector in the New Public Management. Int J Cult Policy 10(2):183–202

Birner J (1999) The place of the Ricardo effect in Hayek’s economic research programme. Revue D’économie Politique 109(6):803–816

Boettke P, Haeffele-Balch S, Storr V (2016) Mainline economics: six nobel lectures in the tradition of Adam Smith. Mercatus Center-George Mason University, Arlington

Bordot F (2022) Artificial intelligence, robots and unemployment: evidence from OECD countries. J Innov Econ Manag 1:117–138. https://doi.org/10.3917/jie.037.0117

Brynjolfsson E, McAfee A (2014) The second machine age: work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W.W. Norton & Co, New York

Buchanan J, Tullock G (1962) The calculus of consent: logical foundations of constitutional democracy. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Calderon-Monge E, Ribeiro-Soriano D (2023a) The role of digitalization in business and management: a systematic literature review. Rev Managerial Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00647-8

Cem I, Küçükaltan E, Sedat T, Akogül E, Bayraktaroglu E (2019) Tourism and innovation: a literature review. J Ekonomi 1(2):98–154

Clayton C, Maggiori M, Schreger J (2023) A framework for geoeconomics (No. w31852). National Bureau of Economic Research, Washington DC

Coase R (1937) The nature of the firm. Economica 4(16):386–405

Comisión Europea (2014) Turismo: periodo de programación 2014–2020 (URL: Turismo - Política Regional - Comisión Europea (europa.eu); consulted March 10, 2022)

Comisión Europea (2019) Un pacto verde europeo (URL: Un Pacto Verde Europeo | Comisión Europea (europa.eu); consulted March 10, 2022)

Cosme I, Santos R, O’Neill D (2017) Assessing the degrowth discourse: a review and analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals. J Clean Prod 149:321–334

Diamandis P, Kotler S (2014) Abundance. Free Press, New York

Diamond P, Vartiainen H (2012) Behavioral economics and its applications. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Easterlin R (1974) Does economic growth improve the human lot? In: David P, Reder M (eds) Nations and households in economic growth. Academic Press Inc, New York

Easterlin R, Angelescu McVey L, Switek M, Sawangfa O, Zweig J (2010) The happiness-income paradox revisited. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(52):22463–22468

EU-Consilium (2019) The Economy of Wellbeing: going beyond the GDP (URL: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/economy-wellbeing/; consulted March 10, 2022)

EU-Consilium (2019) The Economy of Well-Being - Executive Summary of the OECD Background Paper on “Creating opportunities for people's well-being and economic growth”.doc. 10414/18 ADD 1 (URL: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10414-2019-INIT/en/pdf; consulted March 10, 2022)

EU-Horizon Europe (2021) What is horizon Europe? (URL: Horizon Europe | European Commission (europa.eu); consulted March 10, 2022)

European Commission (2022) Semi-annual report on the execution of NextGenerationEU funding operations (URL: NextGenerationEU - European Commission (europa.eu); consulted Octuber, 2022).

European Parliament (2022) Tourism (URL: Tourism | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament (europa.eu). Accessed 10 Mar 2022

European Parliament (2023) Tourism (URL: Tourism | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament (europa.eu). Accessed 10 March 2023

Felicetti AM, Corvello V, Ammirato S (2023) Digital innovation in entrepreneurial firms: a systematic literature review. Rev Managerial Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00638-9

Ferguson F, Moreno D (2014) Gender and sustainable tourism: reflections on theory and practice. J Sustain Tour 23(3):401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.957208

Ferlie E (2017) The new public management and public management studies. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedias (sec. Business and Management), p 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.129

Fernández I (2015) Felicidad organizacional. Ediciones B, Santiago

Fernández S (2015b) Vivir con abundancia. Plataforma Editorial, Madrid

Feyerabend P (1975) Against method: outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. Verso, London

Figini P, Patuelli R (2022) Estimating the economic impact of tourism in the European Union: review and computation. J Travel Res 61(6):1409–1423

Florida R (2010) The great reset: how new ways of living and working drive post-crash prosperity. Random House Canada, Toronto

Galbraith JK (1958) The affluent society. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

García S, Sánchez-Bayón A (2021a) Gestión del cambio y del conocimiento en organizaciones cooperativas y de transformación social. Revista Internacional De Organizaciones. https://doi.org/10.17345/rio27.137-171

García D, Sánchez-Bayón A (2021b) Cultural consumption and entertainment in the Covid-19 lockdown in Spain: orange economy crisis or review? Vis Rev 8(2):131–149. https://doi.org/10.37467/gka-revvisual.v8.2805

García-Vaquero M, Sánchez-Bayón A, Lominchar J (2021) European green deal and recovery plan: green jobs, skills and wellbeing economics in Spain. Energies 14(14):4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144145

Garrison R (2001) Time and money. Routledge, London

Gehrke C (2003) The Ricardo effect: its meaning and validity. Economica 70(277):143–158

Golub A, Lane C (2015) Zombie companies and corporate survivors. Anthropol Now 7(2):47–54

Gómez P (2019) La riqueza de las naciones en el s. XXI. Círculo Rojo, Almería

González E, Sánchez-Bayón A (2021) Rescate y transformación del sector turístico español vía fondos europeos Next Gen EU. Encuentros Multidisciplinares 23(69):1–15

Hayek F (1935) Prices and production. In: Salerno J (ed) Prices and production and other works. Mises Institute, Auburn (2008)

Hayek F (1939) Profits, Interest, and Investment, and other Essays on the Theory of Industrial Fluctuations. In: Hansjörg Klausinger (ed) The Collected Works of F.A. Hayek (vol. 8, Business Cycles Part II, 2012)

Hayek F (1952) The sensory order. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hayek F (1988) The fatal conceit. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hazlitt H (1946) Economics in one lesson. Harper & Row, New York

Hirschman AO (1970) Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states, vol 25. Harvard University Press

Hirschman AO (1993) Exit, voice, and the fate of the German Democratic Republic: an essay in conceptual history. World Polit 45(2):173–202

Huerta de Soto J (2000) La Escuela Austriaca. Síntesis, Madrid

Huerta de Soto J (2006) Money, bank credit, and economic cycles. Mises Institute, Auburn

Huerta de Soto J (2009) The theory of dynamic efficiency. Routledge, London

Huerta de Soto J, Sánchez-Bayón A, Bagus P (2021) Principles of monetary & financial sustainability and wellbeing in a post-COVID-19 world: the crisis and its management. Sustainability 13(9):4655. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094655

INE (2019) Turismo de España (CSTE). Revisión estadística 2019 Serie 2016–2018 (URL: Cuenta Satélite del Turismo de España (CSTE). Revisión estadística 2019. (ine.es); consulted March 10, 2022)

INE (2020) Nota de prensa sobre el sector turístico español (URL: https://www.ine.es/prensa/cst_2020.pdf; consulted on December, 2020)

Jaén-García M (2021) Displacement effect and ratchet effect: testing of two alternative hypotheses. SAGE Open 11(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211003577

Kaldor N (1942) Professor Hayek and the Concertina-effect. Economica 9(36):359–382

Kallis G, Kostakis V, Lange S, Muraca B, Paulson S, Schmelzer M (2018) Research on degrowth. Annu Rev Environ Resour 43:291–316

Keen S (2020) Coronavirus brutally exposes the fallacies underlying neoclassical economics and Globalisation. Revista De Economía Institucional 22(43):17–27

Keynes J (1930) Economic possibilities for our grandchildren. Nation´s Business (1927) y Macmillan (1930, de manera póstuma incorporado en Keynes, J.M. (1963) Essays in persuasion. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, pp 358–373)

Keynes J (1933) The means to prosperity. In: The times (luego desarrollado, como planfleto y publicado por Macmillan)

Keynes J (1936) The general theory of employment, interest and money. Macmillan, London

Keynes J (1937) The general theory of employment. Q J Econ 51(2):209–223

Kirzner I (1973) Competition and entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Kirzner I (1987) Austrian School of Economics. The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (vol 1), pp 145–151

Klausinger H (2012) Introduction. In: Klausinger H (ed) The collected works of F.A. Hayek (vol. 8, Business Cycles Part II, 1–43)

Kraus S, Jones P, Kailer N, Weinmann A, Chaparro-Banegas N, Roig-Tierno N (2021) Digital transformation: an overview of the current state of the art of research. SAGE Open 11(3):21582440211047576

Kraus S, Durst S, Ferreira J, Veiga P, Kailer N, Weinmann A (2022) Digital transformation in business and management research: an overview of the current status quo. Int J Inf Manag 63:102466

Kuifu L, Ning M (2016) A foreign literature review of zombie companies research. Foreign Econ Manag 38(10):3–19. https://doi.org/10.16538/j.cnki.fem.2016.10.001

Kurzweil R (2005) The singularity is near. Penguin Group, New York

Lakatos I (1978) The methodology of scientific research programmes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lin X, Ribeiro-Navarrete S, Chen X, Xu B (2023) Advances in the innovation of management: a bibliometric review. RMS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00667-4

Llena-Nozal A, Martin N, Murtin F (2019) The Economy of Well-being Creating opportunities for people’s well-being and economic growth. SDD WORKING PAPER No. 102. Paris: OCDE. https://doi.org/10.1787/18152031

Marx K (1867–94) Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, vol 3). Meisner, Hanover

Menger C (1871) Grundsätze der volkswirtschaftslehre. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig

Menger C (1883) Untersuchungen uber die Methode der Socialwissenschaften und der Politischen Oekonomie Insbesondere. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig

Mises L (1949) Human action: a treatise on economics. Yale University Press, New Haven

Moss L, Vaughn K (1986) Hayek´s Ricardo effect: a second look. Hist Polit Econ 18(4):545–565

Obanor HQZ (2021) The fourth industrial revolution and its impact on ethics: the new luddites. In: Miller K, Wendt K (eds) The fourth industrial revolution and its impact on ethics: solving the challenges of the agenda 2030. Springer International Publishing, New York, pp 215–224

OCDE (2012) Digital Economy. OCDE, París. (URL: The Digital Economy - 2012 (oecd.org)).

OCDE (2019) The economy of well-being: creating opportunities for people’s well-being and economic growth. OCDE, Paris

Ogunrinde A (2022) The effectiveness of soft skills in generating dynamic capabilities in ICT companies. ESIC Mark 53(3):e286–e286. https://doi.org/10.7200/esicm.53.286

ONU (2012) Defining a new economic paradigm: the report of the high-level meeting on wellbeing and happiness. ONU, New York

ONU-GA (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (UN Resolution A/RES/70/1), containing the goals (passed: Sept. 25, 2015; published: Oct. 21, 2015)

ONU-SG (2012) Secretary-general SG/SM/14204 in message to meeting on “happiness and well-being” calls for “Rio+20” outcome that measures more than gross national income (URL: http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2012/sgsm14204.doc.htm)

ONU-SNDP (2013). Secretariat for the new development paradigm (SNDP)—Working group meeting in Bhutan (URL: http://www.newdevelopmentparadigm.bt/category/resources/)

ONU-UNDP (2013) A million voices: the world we want: a sustainable future with dignity for all. (URL: http://www.worldwewant2015.org/millionvoices)

Parlamento Europeo (2022) El turismo (URL: El turismo | Fichas temáticas sobre la Unión Europea | Parlamento Europeo (europa.eu); consultado el 10/02/2022)

Peacock A, Wiseman J (1979) Approaches to the analysis of government expenditure growth. Public Finance Q 7(1):3–23

Pigou C (1920) Economics of welfare. Macmillan, London

Posner R (1973) Economic analysis of law. Little Brown, Boston

Prause G (2021) The role of cultural and creative industries sector for post-COVID recovery. In: SHS web of conferences, vol 126, pp 06006

Ren M, Zhao J, Zhao J (2023) The crowding-out effect of zombie companies on fixed asset investment: evidence from China. Res Int Bus Finance 65:101979

Ribeiro-Navarrete B, Saura JR, Simón-Moya V (2023) Setting the development of digitalization: state-of-the-art and potential for future research in cooperatives. Rev Managerial Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00663-8

Ricardo D (1817) On the principles of political economy and taxation. J. Murray, London

Robinson J (1962) Economic philosophy. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth

Romer P (2015) Mathiness in the theory of economic growth. Am Econ Rev 105(5):89–93. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151066

Rothbard M (1995) The present state of Austrian economics. Journal Des Economistes Et Des Etudes Humaines 6(1):43–90

Ruys P (2017) A development of the theory of the Ricardo effect. Q J Austrian Econ 20(4):297–335

Samuelson P (1958) Economics. McGraw-Hill, New York

Sánchez Tróchez DX, Cerón Ríos GM, Rivera Martínez WF (2021) Intrapreneurship in small organizations: case studies in small businesses. ESIC Mark. https://doi.org/10.7200/esicm.168.0521.3

Sánchez-Bayón A (2017) Revelaciones conceptuales y lingüísticas de la posglobalización. Carthaginensia 33(64):411–458

Sánchez-Bayón A (2020a) Renovación del pensamiento económico-empresarial tras la globalización. Bajo Palabra 24:293–318. https://doi.org/10.15366/bp.2020.24.015

Sánchez-Bayón A (2020b) Una Historia de RR.HH. y su transformación digital. Rev Asociación Española de Especialistas de Medicina del Trabajo 29(3):198–214

Sánchez-Bayón A (2021a) Balance de la economía digital ante la singularidad tecnológica: cambios en el bienestar laboral y la cultura empresarial. Sociología y Tecnociencia 11(2):53–80. https://doi.org/10.24197/st.Extra_2.2021.53-80

Sánchez-Bayón A (2021b) Urgencia de una filosofía económica para la transición digital: Auge y declive del pensamiento anglosajón dominante y una alternativa de bienestar personal. Miscelánea Comillas 79(155):521–551. https://doi.org/10.14422/mis.v79.i155.y2021.004

Sánchez-Bayón A (2022a) Crisis económica o economía en crisis? Relaciones ortodoxia-heterodoxia en la transición digital. Semestre Económico 11(1):54–73. https://doi.org/10.26867/se.2022.1.128

Sánchez-Bayón A (2022b) From Neoclassical synthesis to Heterodox synthesis in the digital economy. Procesos De Mercado 19(2):277–306. https://doi.org/10.52195/pm.v19i2.818

Sánchez-Bayón A (2022c) Gestión comparada de empresas colonizadoras del Oeste americano. Retos Revista De Ciencias De La Administración y Economía 12(24):330–348. https://doi.org/10.17163/ret.n24.2022.08

Sánchez-Bayón A (2023) Digital transition and readjustmen on EU tourism industry. Stud Bus Econ 18(1):275–297. https://doi.org/10.2478/sbe-2023-0015

Sánchez-Bayón A, Castro M (2022) Historia de la reciente deflación del capital y los salarios en España. Iber J Hist Econ Thought 9(2):111–131. https://doi.org/10.5209/ijhe.82760

Sánchez-Bayón A, Cerdá L (2023) Digital transition, sustainability and readjustment on EU tourism industry: economic & legal analysis. Law State Telecommun Rev 15(2):146–173. https://doi.org/10.26512/lstr.v15i2.44709

Sánchez-Bayón A, García-Ramos M (2021) A win-win case of CSR 3.0 for wellbeing economics: digital currencies as a tool to improve the personnel income, the environmental respect & the general wellness. Revista De Estudios Cooperativos-REVESCO 138:e75564. https://doi.org/10.5209/reve.75564

Sánchez-Bayón A, Trincado E (2020) Business and labour culture changes in digital paradigm. Cogito 12(3):225–243

Sánchez-Bayón A, Trincado E (2021) Rise and fall of human research and the improvement of talent development in digital economy. Stud Bus Econ 16(3):200–214. https://doi.org/10.2478/sbe-2021-0055

Sánchez-Bayón A, García-Vaquero M, Lominchar J (2021) Wellbeing economics: beyond the labour compliance & challenge for business culture. J Leg Ethical Regul Issues 24:1–13

Sánchez-Bayón A, Gonzálezo E, Andreu A (2022) Spanish healthcare sector management in the COVID-19 crisis under the perspective of Austrian economics and new-institutional economics. Front Public Health 10:801525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.801525

Sánchez-Bayón A, Urbina D, Alonso-Neira MA, Arpi R (2023) Problema del conocimiento económico: revitalización de la disputa del método, análisis heterodoxo y claves de innovación docente. Bajo Palabra 34:117–140. https://doi.org/10.15366/bp2023.34.006

Sarfraz Z, Sarfraz A, Iftikar HM, Akhund R (2021) Is COVID-19 pushing us to the fifth industrial revolution (society 5.0)? Pak J Med Sci 37(2):591–594. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.37.2.3387

Schwab K (2016) The fourth industrial revolution. World Economic Forum, Geneva

Schwab K, Malleret T (2019) COVID-19: the great reset. WEF, Genova

Shin H, Perdue RR (2022) Hospitality and tourism service innovation: a bibliometric review and future research agenda. Int J Hosp Manag 102:10317

Song Y, Escobar O, Arzubiaga U et al (2022) The digital transformation of a traditional market into an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Rev Manag Sci 16:65–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00438-5

Steele G (1988) Hayek’s Ricardo effect. Hist Polit Econ 20(4):669–672

Stiglitz J, Rosengard J (2015) Economics of public sector. W. W. Norton, New York

Suresh R (2010) Economy and society. Evolution of capitalism. SAGE, Delhi

Thaler R (2016) Behavioral economics: past, present, and future. Am Econ Rev 106(7):1577–1600. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.106.7.1577

TRAN Committee (2019) European tourism: recent developments and future changes (URL: https://research4committees.blog/tran/ & Research for TRAN Committee - European tourism: recent developments and future challenges | Think Tank | European Parliament (europa.eu); consulted March 10, 2022)

Trincado E, Sánchez-Bayón A, Vindel J (2021) The European Union green deal: clean energy wellbeing opportunities and the risk of the Jevons paradox. Energies 14(14):4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144148

Valero J, Sánchez-Bayón A (2018) Balance de la globalización y teoría social de la posglobalización. Dykinson, Madrid

Wegner D, da Silveira AB, Marconatto D, Mitrega M (2023) A systematic review of collaborative digital platforms: structuring the domain and research agenda. Rev Managerial Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00695-0

Weingast B (2016) Exposing the neoclassical fallacy: McCloskey on ideas and the great enrichment. Scand Econ Hist Rev 64(3):189–201

Wilson T (1940) Capital theory and the trade cycle. Rev Econ Stud 7(3):169–179

Yanuar M (2021) The risk of mainstreaming economic growth and tourism on preventing Covid-19 in Indonesia. Sociol Technosci/sociol Tecnociencia 11(2):94–114. https://doi.org/10.24197/st.2.2021.94-114

Zhao J, Wei C (2023) Zombie companies in China in the COVID-19 era. Int Insolv Rev 32(2):309–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/iir.1501

Zhao J, Wen S, Parry R, Wei C (2021) Eliminating zombie companies through insolvency law in China: striking a balance between market-oriented policies and government intervention. Asia Pac Law Rev 29(2):264–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/10192557.2022.2033083

Zhou J, Xian G, Ming X (2018) The recognition and warning of zombie enterprises: evidence from Chinese listed companies. J Finance Econ 44(4):130–142. https://doi.org/10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.2018.04.010

Zuñiga-Collazos A, Gómez-López JM, Ríos-Obando JF, Vargas-García LM (2023) Innovación y políticas públicas como factores para promover el desarrollo de organizaciones de turismo en Colombia. Retos Revista De Ciencias De La Administración y Economía 13(26):341–355. https://doi.org/10.17163/ret.n26.2023.10

Acknowledgements

Research part of Sánchez-Bayón’s PhD dissertation in the Doctoral Prog. Economics & Business at Universidad de Málaga (UMA), and supported by GESCE-Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (URJC) & GID-TICTAC CCEESS-URJC, and CIELO-ESIC Business & Marketing School.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Bayón, A., Sastre, F.J. & Sánchez, L.I. Public management of digitalization into the Spanish tourism services: a heterodox analysis. Rev Manag Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-024-00753-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-024-00753-1

Keywords

- Tourism services

- Public management & economics

- Next Gen EU

- Digitalization

- Heterodox approaches

- Cornucopists & New-Malthusians

- Knowledge Economy