Abstract

To examine how knowledge-based dynamic capabilities relate to firm performance through the mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation, we analyzed data of a sample of 1047 Portuguese and Spanish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) of all industry sectors. The results reveal that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are associated with firm performance and that the relationship is partially mediated by a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation. This mediation could be explained by the fact that an entrepreneurial orientation to identify and utilize new opportunities is integral to knowledge value creation and extraction, and to avoid pervasive rigidities. Our study sheds light on the mechanisms through which knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are associated with firm performance and helps to explain performance differences among firms. In addition, we provide management insight on how firms can deploy their knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and extract value from them to face change and promote their entrepreneurial orientation and performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As an evolution of the resource-based view (RBV), whereby the organization is conceived as a nexus of resources (Barney 1991), dynamic capabilities have emerged as an approach for understanding how organizations create, extend, and modify their resource base (Kurtmollaiev 2020). Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (Eriksson 2014) are defined as those that highlight the role of knowledge as a structural element of dynamic capability (Denford 2013; Faccin et al. 2019), focusing on the way companies learn, assimilate new knowledge, and adapt. Since the potential of dynamic capabilities to improve organizational performance was conceptually proposed in Teece et al.’s (1997) seminal article, empirical studies, with a few exceptions (e.g., Wilden et al. 2013), have mostly supported this potential. However, the growing literature also reports that the relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm performance is more complex than a direct effect and may be mediated by other variables (Bitencourt et al. 2020; Fainshmidt et al. 2016; Karna et al. 2016; Pezeshkan et al. 2016). This emerging stream of research is still limited and mostly explores how changes in resources mediate that relationship (Schilke et al. 2018).

Knowledge of how companies transform their dynamic capabilities into performance remains understudied. Dynamic capabilities refer to the deliberate and regular actions of configuration and reconfiguration of resources (Kurtmollaiev 2020). However, changing the endowment of resources is not a sufficient condition to increase performance (e.g., Miao et al. 2017; Priem and Butler 2001). For this internal change to be translated into performance, a firm needs to deploy valuable, rare, costly to imitate, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources and capabilities (Barney 1991). Moreover, these resources and capabilities need to be structured, bundled, and leveraged in accordance with the competitive environment (Sirmon et al. 2007, 2011). A possible way to do these things is to develop an entrepreneurial orientation (EO), defined as “the strategy making processes that provide organizations with a basis for entrepreneurial decisions and actions” (Rauch et al. 2009, p. 762) that is used by managers to guide the company’s use of their resources and capabilities (Miao et al. 2017). Indeed, it has been theoretically proposed (Helfat and Martin 2015; Teece 2007; Zahra et al. 2006) and empirically tested (Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2017) that dynamic capabilities influence the intensity of a company’s EO. EO is important to turn dynamic capabilities into firm performance because a high degree of EO prevents the creation of core rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992; Rosenbusch et al. 2013).

Considering the above arguments, our goal is to answer two key research questions: (1) How do dynamic capabilities relate to firm performance, and (2) How does EO mediate that relationship? To answer these questions, we theoretically propose that for a firm to be able to take advantage of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities without being hindered by possible rigidities, a high level of EO is needed. EO mediates the relationship between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance, because configuring their knowledge base becomes an essential process for firms to adapt, and the exploitation of this knowledge should be undertaken with an EO (Hughes et al. 2022).

To test our model we performed an empirical study with 1047 small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) from Portugal and Spain. Aside from their economic importance, SMEs have features that make them an especially suitable setting for our research. SMEs often suffer from constraints to reconfigure internal resources (e.g., a lack of human and financial resources for R&D, and resource lock-ins) despite their lighter bureaucracy (Heider et al. 2021) and greater flexibility (Wu and Deng 2020). Moreover, SMEs are especially vulnerable to competition and environmental change (Wang et al. 2011), which puts them under survival pressure, demanding that they become adaptable and rethink their traditional ways of managing resources to respond to uncertainty (Do et al. 2022). This makes knowledge-based dynamic capabilities especially valuable for SME performance (Wang et al. 2011) but also raises difficulties in creating advantage. Both countries provide an appropriate context to test our model because SMEs constitute the backbone of these two national economies, representing in 2021Footnote 1 about 80% of private employment (79.81% and 80.28%, respectively for Portugal and Spain), clearly above European Union Figures (76.39%) (Eurostat).

We contribute to strategy and organizational literatures in five ways. First, we advance an explanation of the role of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities as key tools for SME performance despite their resource constraints. Second, we shed light on the mechanisms through which knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are associated with firm performance, which has been considered “an area of weakness in the current literature” (Schilke et al. 2018, p. 392). By exploring the mediating role of firms’ EO, we support the existence of both a direct and a mediated effect of dynamic capabilities on firm performance (Bitencourt et al. 2020; Fainshmidt et al. 2016; Karna et al. 2016; Pezeshkan et al. 2016). Our study goes beyond the mainstream of research that has focused on exploring how change in resources mediates the dynamic capabilities-firm performance link (Schilke et al. 2018), while answering calls for a more robust theorizing on the vision of dynamic capabilities as a driver of EO (Wales 2016). Third, while research has tended to focus on the moderating role of strategic orientations in the relationship between dynamic capabilities and performance (e.g., Hernández-Linares et al. 2021; Hock-Doepgen et al. 2021), our study reveals that such orientations may help firms to extract the most value from their knowledge-based dynamic capabilities. Fourth, since few studies have approached the relationship between EO and its determinants (Arzubiaga et al. 2019), the paper extends the discussion regarding the role of EO by focusing on one of its potential antecedents: dynamic capabilities, a variable that has received little attention (Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2017). Our study corroborates the influence of dynamic capabilities in a firm’s EO, which could be very important and even more salient in the case of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (Cope 2005; Dess et al. 2011). Finally, our results contribute to a deeper understanding of why some SMEs perform better than others. Our study has practical implications, in that the results provide managers with insight regarding how SMEs can face change and improve their performance through deploying their knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and extract value from them via EO.

2 Theory development and hypotheses

The dynamic capabilities framework (Teece et al. 1990) evolved from the RBV, which explains how a company may have better performance by achieving a competitive advantage, taking the firm as a nexus of resources and capabilities (Barney 1991). However, RBV is static in nature, and considering that organizations must develop a process of learning to adapt to environmental changes, Teece and colleagues (1997) developed the framework of dynamic capabilities, which they defined as a “firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (p. 516). Teece et al.’s (1997) seminal work views dynamic capabilities as abilities (capabilities, capacities, competences) that are resident in organizational processes and management teams, being, hence, unique and inimitable (Kurtmollaiev 2020). A second stream of work on dynamic capabilities, routine-based and rooted in evolutionary economics (Nelson and Winter 1982), begins with the work of Eisenhardt and Martin (2000, p. 1107), who defined dynamic capabilities as “the firm’s processes that use resources—specifically the processes to integrate, reconfigure, gain and release resources—to match and even create market change”. This second approach views dynamic capabilities as complex and multidimensional organizational routines that create variation necessary for changes in other organizational routines (Kurtmollaiev 2020).

The two approaches have differences (Peteraf et al. 2013) regarding the role of dynamic capabilities in rapidly changing environments and whether they are necessary but not sufficient for competitive advantage and a source of sustainable advantage. Di Stefano et al. (2014) delve into those contradictions by highlighting how both approaches understand the nature of dynamic capabilities and the issue of agency (Kurtmollaiev 2020), opening a way to clarify and better understand what dynamic capabilities are. Thus, Kurtmollaiev (2020) addresses contradictions of previous approaches by emphasizing that dynamic capabilities are regular actions that emerge from an individual’s intentions to change the status quo and that have to be accompanied by the “organizational members’ readiness for changes that regularly emanate from a specific individual” (pp. 9–10).

Dynamic capabilities have been proposed as determinants of firm performance (e.g., Makadok 2001; Schilke 2014a; Teece et al. 1997) but growing empirical evidence suggests that this relationship may be more complex and nuanced (Hernández-Linares et al. 2021; Wang and Ahmed 2007). To shed light on this relationship we focus on knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (Zahra and George 2002). Eriksson’s (2014) review established that in the empirical realm, there are two approaches to dynamic capabilities: the first focuses on specific processes, while the second considers generic knowledge-related processes. In line with recent work (Hernández-Linares et al. 2021) we follow this second approach because it is the most common in the literature and provides more generalizable results than the approach focused on idiosyncratic processes (Eriksson 2014). Specifically, we follow Pavlou and El Sawy (2011), considering that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities comprise four regular actions: sensing (generating, disseminating, and responding to market intelligence), learning (expanding the new knowledge repertoire), integrating (assimilating new knowledge), and coordinating (orchestrating resources, tasks, and activities). This approach is well suited for our study because the access to knowledge and its use allows organizations to recognize, pursue, and take advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities (Dushnitsky and Lenox 2006; Randolph et al. 2017; Simsek and Heavey 2011).

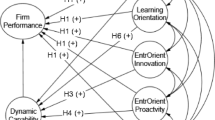

We choose EO as a possible mechanism mediating the relationship between a firm’s knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and its performance based on theoretical arguments (Miao et al. 2017; Kurtmollaiev 2020; Schilke et al. 2018; Zahra et al. 2006) and empirical evidence (Hughes et al. 2022; Kallmuenzer et al. 2018; Rauch et al. 2009; Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. 2018; Rosenbusch et al. 2013; Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2017; Wales et al. 2021). In our model, knowledge-based dynamic capabilities allow the reconfiguration of the resource base by helping the company to better identify opportunities that will potentially improve firm performance, while EO helps firms to maximize the performance that they may extract from such capabilities (Fig. 1).

2.1 Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance

Although regular change of the organizational resource base cannot be equated to positive results (Arend and Bromiley 2009), it has been theorized that this systematic and intentional change does bring benefits (Peteraf et al. 2013) because organizations learn how to effectively change without incurring excessively high costs (Fainshmidt et al. 2016). Therefore, dynamic capabilities will boost efficiency and efficacy, and ultimately firm performance (Di Stefano et al. 2014; Peteraf et al. 2013; Schilke et al. 2018). By regularly improving daily problem solving (Zollo and Winter 2002), dynamic capabilities may also enhance operational efficiency. By constantly improving and renewing resource base and problem-solving strategies (Danneels 2015) companies may gain alignment with their competitive environment. As Schilke et al. (2018) point out, dynamic capabilities can induce a VRIN framework, and in the process, companies may adapt to their environments as well as help shape them (Augier and Teece 2009). Considering that dynamic capabilities influence the effectiveness of responses to market needs as the environment evolves (Iyer et al. 2019), and that the use of dynamic capabilities is fundamental to exploit future opportunities (Zahra et al. 2006), it seems possible to also argue that firms endowed with superior dynamic capabilities identify opportunities earlier, adapt to changes more easily, and seize perceived opportunities better (Teece et al. 1997). The association between dynamic capabilities and firm performance was conceptually established by the first theory papers in the field (e.g., Teece et al. 1990, 1997).

While the arguments above are plausible, there are mixed perspectives among researchers regarding the relationship between an organization’s dynamic capabilities and its performance (Pezeshkan et al. 2016). Some studies report insignificant or negative effect of dynamic capabilities (e.g., Arend 2014; Wilden and Gudergan 2015), including knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (e.g., Wilden et al. 2013) on organizational performance, supporting the idea that the commitment of resources required to maintain and implement dynamic capabilities (Helfat and Peteraf 2015) may be equal to or even outweigh potential benefits (Winter 2003; Zahra et al. 2006). Differently, other studies report that dynamic capabilities (e.g., Dejardin et al. 2023; Schilke 2014a), and specifically knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (e.g., Pavlou and El Sawy 2011), are positively associated with performance. The results of this last stream of work seems to be mostly in literature on dynamic capabilities in general (Bitencourt et al. 2020). Based on such evidence and considering that dynamic capabilities such as core capabilities allow firms to identify new opportunities to apply the accumulated knowledge base (Leonard-Barton 1992), we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are positively associated with firm performance.

2.2 Entrepreneurial orientation as a partial mediator of the knowledge-based dynamic capabilities: firm performance relationship

We next explain why EO partially mediates the association between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance. We start by discussing why knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are associated with EO.

2.2.1 Knowledge-based dynamics capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation

The influence of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities on EO was first proposed by Zahra and colleagues (2006), who state that dynamic capabilities help companies to more quickly exploit the strategic opportunities identified. Teece (2007) also theorized that maintaining and transforming dynamic capabilities in performance demands entrepreneurial management. A firm’s ability to understand its environment is a necessary condition for exploiting fleeting opportunities (Engelen et al. 2014). Indeed, a firm with a “sensing capability” can grasp new market trends and uncover new business opportunities overlooked by competitors (Álvarez and Barney 2007). In addition, to be entrepreneurial, organizations need to scan their environment proactively—a process of exploration that implies the ability to learn (Rhee et al. 2010). Thus, and considering that sensing and learning capabilities are two of the dimensions of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities, it seems reasonable to posit that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities will make it easier for a company to build and reconfigure the knowledge base necessary for recognizing, pursuing, and taking advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities (Dushnitsky and Lenox 2006; Randolph et al. 2017; Simsek and Heavey 2011).

The crucial influence of dynamic capabilities in a firm’s EO (Floyd and Lane 2000; Helfat and Martin 2015; Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2017) is even more evident in the case of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities, since entrepreneurship involves a process of learning (Cope 2005), and learning consists of the acquisition, integration, and exploitation of knowledge-based resources (Dess et al. 2011). In the same vein, the literature emphasizes that firms must use their knowledge base to analyze the external environment and detect possible opportunities and threats (Do et al. 2022), which is directly related to its ability to refine its existing skills sets and competences (Kreiser 2011), thus fostering EO.

Such influence can be attributed to several EO dimensions. Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities will endow companies with the knowledge resources (Kyrgidou and Spyropoulou 2013) needed to nurture innovativeness, defined as an organization’s efforts to discover potential opportunities (Lumpkin et al. 2010). Similarly, knowledge-based dynamic capabilities help companies to improve their proactiveness or the company’s efforts to recognize opportunities and seize them (Lumpkin et al. 2010) because their stronger communication links will help to achieve a more accurate assessment of their attractiveness (Rothaermel and Alexandre 2009) and a more efficient exploitation of the available information (Liao et al. 2003).

Regarding the willingness to commit resources to venture into the unknown or take risks (Hughes and Morgan 2007; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005), knowledge-based dynamic capabilities provide valuable and updated information and knowledge that helps them to make risky decisions (Liao et al. 2003) and recover from competitors’ actions and responsiveness (Engelen et al. 2014). Moreover, considering that dynamic capabilities counter structural inertia, they also help to better anticipate competitors’ actions (Barringer and Bluedorn 1999) and implement counter actions (Green et al. 2008). The presence of systematic actions fostering learning and updating knowledge also prepares individuals and teams to develop and perform independent and autonomous actions (Caloghirou et al. 2004).

Finally, an EO will be necessary to ensure that inertia and resistance to change do not limit the potential of new resources generated by the knowledge-based dynamic capabilities to improve firm performance (Leonard-Barton 1992). This means that for a firm to generate sustained competitive advantage, it needs to rethink how it creates and captures value (Helfat and Martin 2015) and an EO may help to support the search and exploitation of new opportunities, being proactive regarding marketplace opportunities, countering inertia and stagnation, and capturing the business value (Kallmuenzer et al. 2018; Wales et al. 2021). The still limited empirical research has confirmed the positive influence of dynamic capabilities on EO (Dias et al. 2021; Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. 2018; Ruíz-Ortega et al. 2017). Therefore, in line with both the theoretical idea that companies “with strong dynamic capabilities are intensely entrepreneurial” (Teece 2007, p. 1319) and that EO is determined by its resources and capabilities (Helfat and Martin 2015), and considering the growing empirical evidence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are positively associated with firm entrepreneurial orientation.

2.2.2 Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance

In relentlessly shifting environments companies need to be constantly looking for new opportunities (Rauch et al. 2009). In so doing, the development of an EO emerges as a candidate explanation for why and how certain companies are able to renew their capabilities more than others (Morris et al. 2011). The bulk of EO literature has explored its link with business performance (Wales et al. 2013, 2021). We consider EO as a combination of different organizational processes (Lumpkin and Dess 1996) or, according to Wales et al. (2020, p. 644), “the complimentary organizational processes, routines, structural choices, and cultural climates which foster and support a pattern of new entry”. The synergistic combination of those organizational processes (Hughes and Morgan 2007; Lumpkin and Dess 1996) is expected to positively influence organizational performance, although they can also bring some additional costs (Hughes and Morgan 2007). Thus, innovativeness is expected to positively change how the company embeds market learnings in its action repertoires. Proactiveness allows companies to take advantage of new opportunities because it predisposes them to move fast rather than to respond reactively (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). Similarly, proactiveness and risk-taking are considered “two important entrepreneurial features that shape how a firm acquires and utilizes its resources” (Gunawan et al. 2016, p. 581). Being more entrepreneurial, a firm potentially senses and seizes opportunities better than competitors, which confers a learning advantage.

Some scholars report a negative relationship between a firm’s EO and its performance (e.g., Cossío-Silva et al. 2015; Vega-Vázquez et al. 2016), arguing that EO alone is not enough to generate a positive performance, at least in the short term (Cossío-Silva et al. 2015; Vega-Vázquez et al. 2016), and other scholars find a curvilinear inverted U-shaped relationship between the two, revealing potentially adverse outcomes resulting from too much EO (Tang et al. 2008; Tang and Tang 2012). However, a third group of studies, which seems to be the most numerous according to a recent literature review (Wales et al. 2021), reports a linear and positive impact of EO on performance (e.g., Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Zahra and Covin 1995), even in the SME context (e.g., Ferreira et al. 2021). Based on this evidence, and considering that EO allows organizations to explore and pursue new value opportunities not constrained by its current resource position (Wales et al. 2021), we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Entrepreneurial orientation is positively associated with firm performance.

2.2.3 The mediating role

According to Leonard-Barton’s (1992) definition of core capabilities, knowledge-based dynamic capabilities can be considered core capabilities because they may distinguish a company strategically and provide a competitive advantage. As core capabilities, knowledge-based dynamic capabilities may be institutionalized, leading to core rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992). Thus, for instance, such institutionalization could lead to knowledge and knowledge-based skills remaining tacit, i.e., uncodified and in employees’ heads (Tsoukas 2003). EO may help firms to cultivate the bright side of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities by minimizing the dysfunctionalities of the core rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992) because the knowledge identified, learned, integrated, and deployed through knowledge-based dynamic capabilities may be transformed into valuable products and/or services via an EO that promotes cultures of learning and initiative (Wales et al. 2021) rather than overprotecting existing processes and routines. In addition, entrepreneurially-oriented firms may also be open to empowering their employees and teams to make decisions with greater latitude, improving responsiveness to market needs (Covin et al. 2021). Therefore, beyond being a key ingredient for superior firm performance (Wales et al. 2021), EO also plays a key role in helping firms to overcome the paradox of extracting value of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities without being hampered by their dysfunctional flip side, sometimes called the Icarus paradox (Miller 1992), the excess of confidence in existing solutions. Thus, EO helps companies to channel knowledge-based dynamic capabilities toward company goals (in this case better performance) without falling into the core rigidity trap (Leonard-Barton 1992) that can arise as a consequence of an excessive and routine institutionalization of existing knowledge-based dynamic capabilities.

The above arguments reveal that EO mediates the relationship between the absorptive capacity (a particular type of dynamic capability) and firm performance in the singular context of small family firms (Chaudhary and Batra 2018). Such a reasoning leads us to propose a meditation process whereby EO transforms the knowledge generated through knowledge-based dynamic capabilities into an opportunity sensing and seizing orientation, which facilitates changes in the way a firm operates, thus contributing to firm performance. However, given that other mediating mechanisms (mainly change in the resource base) have been identified (Fainshmidt et al. 2016; Schilke et al. 2018), we posit that EO is a partial mediator between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and the firm’s performance. Hence:

Hypothesis 4

Entrepreneurial orientation partially mediates the positive relationship between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance.

3 Method

3.1 Research design and data collection

The data, which are part of a wider research project (e.g., Hernández-Linares et al. 2018, 2020, 2021), were collected at the beginning of 2015 in Spain and Portugal. These two countries have been previously investigated as a global Iberian market (Neves et al. 2020) due to their similarities, which are based on their geographical and linguistic proximity (Margaça et al. 2021), historical evolution (i.e., they are both late comers to the democratic process, Linz 1979; Margaça et al. 2021), commercial and cultural relations (Neves et al. 2020), and even entrepreneurship patterns (Medeiros et al. 2020). Both are market economies with a highly regulated model of capitalism. During the economic crisis, both Portugal and Spain faced pressures from the so-called “Troika” (joint mission of the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund) in return for aid (García Calavia and Rigby 2020). Also, the economic crisis and the resulting austerity policies had a strong impact on the labor market in both countries (Margaça et al. 2021).

Lastly, together with Greece and Italy, Portugal and Spain have been considered as the greatest risks to the future of the EU economy (Atukeren et al. 2013), and studies about the sources of their firms’ success are thus of vital importance. Additionally, in both countries the 2007–2009 global financial crisis lengthened in time, making their SMEs the ones that most suffered the crisis in the European Union (Menéndez-Pujadas et al. 2017). Economic recessions can severely affect the survival or performance of business organizations (Srinivasan et al. 2005) and knowledge about how firms deal with recessions will be especially necessary in the current context of the increasingly complex, uncertain, dynamic, and fast-changing environment (Cosenz and Bivona 2021). Therefore, although our data were collected several years ago (2015), there are reasons to believe that the empirical pattern that has emerged in the interim has valid implications for the current context.

Our target firms came from the SABI database (Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos—System of Iberian Balance Sheets), which offers information pertaining to Spanish and Portuguese companies. As is common in literature (e.g., Obeso et al. 2020), companies affected by special situations such as wind-up, liquidation, insolvency, or zero activity were excluded. Overall, our population consisted of 125,901 SMEs across all sectors, with SMEs being defined as non-listed private companies having between 10 and 249 employees (Stanley et al. 2019). The measures (details below) of the three key variables of the study were translated from English to Spanish and Portuguese, and then back translated. Both versions were pretested in the respective countries, and personalized invitations to complete an online, telephone, and paper survey were sent to CEOs or senior managers, including an offer to share summary reports as an incentive.

Of the 27,176 companies randomly selected from the database, 1484 surveys were returned, yielding an initial response rate of 5.46%. However, only 1066 of those were usable, resulting in a final response rate of 3.92%, a figure comparable to that reported by other studies targeting top management teams in Europe (e.g., De Massis et al. 2018; Stanley et al. 2019). The sampling error was 2.99% within 95% confidence limits (z = 1.96; p = q = 0.5), which is lower than that suggested by previous studies on dynamic capabilities (e.g., a sampling error of 8.4% by Nieves and Haller 2014, and of 4.3% by Hernández-Linares et al. 2021).

Primary information was augmented with secondary information retrieved from the SABI database. Thus, after excluding those surveys whose secondary data for all variables considered in this study were not available, our final sample comprises 1047 SMEs (551 from Portugal and 496 from Spain). The mean number of employees per firm was 35.8 (SD = 36.79), and the mean age of the firms was slightly over 23 years (SD = 14.45). Our sample (see Table 1) is representative of the study population in terms of both size and industry.

3.2 Measures

Respondents (CEOs and senior managers) were asked to describe their firms through a five-point Likert scale (from 1 to 5). The five anchors were adapted for each measure.

3.2.1 Dependent variable

A five-item scale (Hernández-Linares et al. 2020) was used to measure firm performance (α = 0.83). Subjective measures of performance are valuable in that they capture more than a single performance element (Rodríguez et al. 2004) and provide information about qualitative performance aspects (O’Connor et al. 2015). In addition, objective measures are not more predictive than subjective measures (Hoffman et al. 1991); they are “only as reliable as the product market definitions that underlie them” (Ngai and Ellis 1998, p. 128), which suggests that subjective measures are valid. Hence, considering the last 3 years, respondents rated their firms’ performance on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “much worse” to “much better” than their main competitors with respect to return on assets (ROA), growth in sales, market share, quality of products, services, or programs, and finally the development of new products, services, or programs.

3.2.2 Independent variable

Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (α = 0.94) were measured with the 19-item scale from Pavlou and El Sawy (2011) and built as a second-order construct with four dimensions: sensing (4 items), learning (5 items), integrating (5 items), and coordinating capabilities (5 items). Respondents were asked to describe their firms through a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) shows that all standardized factor loadings exceeded the 0.50 cut-off for practical significance (Hair et al. 2006) and that both first- and second-order paths from the latent constructs to their corresponding items were significant at the 0.001 level (t > 2.0), providing evidence of convergent validity (Kohli et al. 1998) (see “Appendix 1”). The fit indices of the second-order four-factor model are satisfactory: (χ2[143] = 1156.85, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI and IFI = 0.92, GFI = 0. 89, and TLI = 0.91).

3.2.3 Mediating variable

EO (α = 0.88) was measured through the scale validated by Hughes and Morgan (2007; see also Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2017, and Stanley et al. 2019), which comprises five dimensions (Lumpkin and Dess 1996): risk-taking (3 items), innovativeness (3 items), proactiveness (3 items), competitive aggressiveness (3 items), and autonomy (6 items). A five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), was used. CFA shows that 17 of the 18 standardized factor loadings exceeded the 0.50 cut-off for practical significance (Hair et al. 2006). Both first- and second-order paths from the latent constructs to their corresponding items were significant at the 0.001 level (t > 2.0), providing evidence of convergent validity (Kohli et al. 1998) (see “Appendix 1”). The second-order five-factor model fits the data satisfactorily: (χ2[128] = 358.97, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI and IFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96).

3.2.4 Discriminant validity

We calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) for knowledge-based dynamic capabilities, EO, and firm performance. All constructs exhibited AVE levels greater than 50%, and all AVE scores were higher than the squared construct correlations (see “Appendix 2”), which ranged from 0.13 to 0.47, confirming the discriminant validity (Hair et al. 2010). To test if knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (four factors/dimensions), EO (five factors/dimensions), and firm performance (five items) represent different constructs, CFA were performed. The three-factor model fits the data satisfactorily (χ2[800] = 2667.21, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI and IFI = 0.92, GFI = 0.88, TLI = 0.91), and better than (1) a model in which knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and EO are merged (Δχ2[2] = 581.84, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI and IFI = 0.90, GFI = 0.86; TLI = 0.89), (2) a model in which EO and firm performance are merged (Δχ2[2] = 1255.50, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.61, CFI and IFI = 0.87, GFI = 0.81, TLI = 0.86), and (3) a model in which the three constructs are merged (Δχ2[2] = 581.84, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05, CFI and IFI = 0.90, GFI = 0.86, TLI = 0.89).

3.2.5 Control variables

We first controlled for the country (0 = Portugal; 1 = Spain). Despite a certain degree of homogeneity within the Iberian Peninsula (Stanley et al. 2019), we cannot discount some cultural specificities or unobserved heterogeneity among countries (Hofstede 2001). Second, given that larger firms may dedicate more resources to developing their change routines (Schilke 2014b) and access to external resources more easily than smaller firms, which may affect firm performance (Zahra and Nielsen 2002), we controlled for firm size, measured as the logarithm of the total number of employees. Then, considering that businesses of different industries may exhibit different organizational and environmental characteristics (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005), we controlled for firm industry by following NACE coding (statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community). Manufacturing, construction, and services sectors were included as control variables, with the primary sector being used as the default. We controlled for firm age (measured as the years from the firm’s foundation) because firms of different ages can exhibit different behaviors that lead to differences in performance (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Finally, we controlled for firm past performance, as it could improve organizational slack resources and encourage entrepreneurial activities (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Specifically, and given the impossibility of having a subjective measure of performance of past years, we introduced the return on equity (ROE) of 2014.

3.3 Multicollinearity and common method bias

Correlation coefficients between key variables are lower than 0.58 and variance inflation factors (VIFs) are under 10.06. Given that VIFs were higher than 5, it could point to a multicollinearity problem, but because the condition indexes were lower than 6.56 (under the limit of 30), multicollinearity does not appear to seriously affect our model fit and hypothesis testing (Hair et al. 2010). To further mitigate multicollinearity concerns, the variables were converted to Z-scores.

As the data were collected from a single source at a single point in time, we adopted several procedures to deal with common method variance (CMV) (Podsakoff et al. 2003; Rindfleisch et al. 2008). First, the confidentiality of the respondents was guaranteed, and respondents were assured that results would be reported only in aggregated form (Zobel 2017), thereby decreasing the risk of social desirability bias (Soluk et al. 2021). Second, we arranged the questions in such a way that participants would not notice any direct connection between the variables (Soluk et al. 2021). Third, a pretest was performed to ensure minimum ambiguity in the survey’s questions/items (Obeso et al. 2020).

We also adopted statistical procedures to test if CMV affected our results. First, a Harman’s (1967) single-factor test was conducted by loading all items into an exploratory factor analysis. This yielded seven factors with an eigenvalue exceeding 1.0. The total variance of the first unrotated factor was 29.73%. The rotated solution, using varimax rotation, revealed similar results. A single factor did not emerge, and no factor accounted for most of the variance, which suggests that CMV is unlikely to distort our results. Then, a common method factor model was estimated, by loading all items on one method factor (Podsakoff et al. 2003). The overall first statistics for the one-factor model were not satisfactory (χ2(812) = 9971.35, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.61, IFI = 0.61, TLI = 0.59, and RMSEA = 0.10) compared with our theoretical model (χ2(800) = 2667.21, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.92, IFI = 0.92 and RMSEA = 0.05).

3.4 Statistical analysis

Hypotheses were tested using ordinary least squares regressions. Specifically, to evaluate the impact of dynamic capabilities on firm performance the basic equation is expressed as follows:

where firm performancei represents the performance of the firm i, KBDCi represents the knowledge-based dynamic capabilities of firm i, the symbol Xi represents the set of control variables explained in Sect. 3.3, and ϵi is the random error term.

To explore the mediating effect of EO, the following specifications were employed:

where EOi represents the EO for firm i. To investigate whether the linkage between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance is mediated by EO, we followed the steps described by Baron and Kenny (1986), as is common in literature (e.g., Dorfleitner and Nguyen 2022; Obeso et al. 2020). After running a regression with firm performance as the dependent variable and considering only the control variables (Model 1), we run the Eq. 1 (Model 2). After performing Model 2, we run a regression with EO as the dependent variable (Eq. 2, Model 3), KBDC being the independent variable and keeping a series of control variables as in Model 1. The coefficient α1 represents the total effect of KBDC on EO. Subsequently, the explained variable in Model 4 (see, Eq. 3), i.e., firm performance is regressed on the mediating variable EO, the main explanatory variable KBDC, and the same set of control variables. The coefficient γ1 measures the effect of KBDC under the influencing mechanism of EO. The coefficient γ2 measures the impact of EO in firm performance. For a partial mediation to exist, the coefficients α1, β1, γ1, and γ2 must be significant and the absolute value of γ1 must be smaller than that of β1. In other words, the coefficient of the variable KMDC when paired with the variable EO (Eq. 3) must be smaller than in the model without the variable EO (Eq. 1).

Although Baron and Kenny’s (1986) methodology is commonly applied in research (e.g., Heidt et al. 2022; Rubio-Andrés et al. 2022), it has been criticized because the conclusions about mediation are not sufficiently meaningful and an assumption is made regarding the normality of the variable distribution (Zhao et al. 2010). Therefore, and in line with recent studies (e.g., Heidt et al. 2022; Ngo et al. 2022), we also used the PROCESS macro (model 4) for SPSS V 3.5 (Hayes 2018; Hayes and Little 2018), which uses ordinary least squares regression to determine un-standardized path coefficients of the direct, indirect, and total effect (Heidt et al. 2022). We generated 5000 bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals using the 1047 responses leading to a level of confidence of 95% for all confidence intervals.

4 Results

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations. Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities correlate with manufacturing sector, services sector, firm age, and firm performance. Firm performance correlates with firm size, construction sector, services sector, and firm age. EO correlates with country, services sector, firm performance, and knowledge-based dynamic capabilities.

The research model was tested by using hierarchical Ordinary Least Squares regression (Table 3). In Models 1–4 the dependent variable is firm performance; in Models 5 and 6 the dependent variable is EO (the mediating variable in our research model).

In Models 1 (dependent variable: performance) and 5 (dependent variable: EO), the seven control variables were included. In the case of Model 1, firm size and firm age showed a significant association with firm performance (β = 0.08, p < 0.001, and β = − 0.07, p < 0.001, respectively), suggesting that bigger versus smaller and younger versus older firms have higher levels of firm performance. In the case of Model 5, country and firm age (β = − 0.06, p < 0.01, and β = − 0.04, p < 0.05, respectively) showed a significant association with firm EO, suggesting that Spanish firms are less entrepreneurially oriented than Portuguese firms, and that younger firms are more entrepreneurial than older firms.

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, knowledge-based dynamic capabilities were entered in Model 2 and Model 5, respectively. Findings showed a significant and positive association between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance (Model 2: β = 0.23, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities also showed a significant and positive association with EO (Model 6: β = 0.31, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. Next, to test Hypothesis 3, EO was entered in Model 3, findings showing a significant association of this variable with firm performance (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Hence, Hypothesis 3 was also supported by our results.

Finally, to test for the mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 4), we followed Baron and Kenny’s (1986) four-step procedure (see Table 3). The first step requires that the independent variable (knowledge-based dynamic capabilities) significantly predicts the mediator (EO). The results show that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities predicted EO (Model 6: β = 0.32, p < 0.001). The second step requires that the independent variable significantly predicts the dependent variable: knowledge-based dynamic capabilities were significantly associated with firm performance (Model 2: β = 0.23, p < 0.001). The third step demands that the mediator (EO) significantly predicts the dependent variable (firm performance). The results show that EO predicts firm performance (Model 3: β = 0.30, p < 0.001). The final step for a partial mediation to exist establishes that the relationship between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance decreases when the mediator (EO) is introduced into the regression equation. The results show (Model 4) that the association between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance decreases by almost one third (from β = 0.23 to β = 0.09, p < 0.001), thus indicating partial mediation. We also use PROCESS macro to study direct and indirect influences. The results (“Appendix 3”) confirm the validity of the positive direct association of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities with firm performance as well as the positive indirect association through EO. This finding supports Hypothesis 4.

5 Discussion

Our hypothesized model posited that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities would be associated with firm performance, and that the relationship would be partially mediated by the entrepreneurial orientation. The findings support all hypotheses. First, the results support the direct and positive association of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities with firm performance (H1 supported). This contradicts Wilden et al. (2013) but is consistent with other studies reporting that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities support and enhance better business performance (e.g., Chien and Tsai 2012, 2021; Colombo et al. 2020; Morgan et al. 2009). Thus, SMEs’ capabilities to deploy and combine knowledge-based resources contribute to an effective response to changing market needs (Iyer et al. 2019) or, as previously suggested (Fabrizio et al. 2022), “[d]ynamic capabilities can help SMEs to examine the environment, understand the market, and create and seize opportunities”. Differently from Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), our study suggests that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities, per se, may lead to higher performance. This finding is especially important in the SMEs context, given that SMEs often have resource limitations (Do et al. 2022) and knowledge-based dynamic capabilities may help these firms to make the right decisions and be key in offsetting such constraints.

In practical terms, this implies that managers should recognize the importance of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities as a first step to extract value from the organization’s stock of knowledge and from the knowledge it may have access to. Once managers recognize the importance of these capabilities to optimize companies’ resources utilization and capabilities “in keeping with the appropriate deployment of their distinctive competences” (Dejardin et al. 2023, p. 1705), they should promote knowledge-based dynamic capabilities. For example, by using technologies to screen customer data, generating contexts or situations for boosting informal communication and thereby make the transmission of knowledge easier, or developing an organizational culture that facilitates information exchange among different levels and departments within the organization (Hernández-Linares et al. 2021). In addition, considering that in today’s business environment most firms face key digital transformation challenges that demand diverse knowledge from diverse origins (Bouncken et al. 2021), this result suggests that the knowledge-based dynamic capabilities constitute a key element in helping SMEs to face those challenges. Future studies may explore this topic.

Second, Hypothesis 2, which proposes that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are positively associated with a firm’s EO, is also supported. This finding corroborates the key role of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities in building an EO (Floyd and Lane 2000; Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2017) and confirms that in the SMEs context “the real benefits of knowledge acquisition also accrue when firms use it to inhabit relevant strategic orientations from such knowledge” (Chaudhary and Batra 2018, p. 1212). This result is also in line with the idea that the ability of some firms to create, discover, and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities in a continuous manner resides in the dynamic capabilities developed by the firm (Zahra et al. 2006). This finding has important implications for SMEs managers because it reveals that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities may be a powerful tool to respond to an unstable environment and create or discover and exploit new entrepreneurial opportunities.

Third, our results also support Hypothesis 3, which states that EO is positively associated with firm performance, corroborating that EO is a key ingredient for firm success (Rauch et al. 2009; Rosenbusch et al. 2013) and specifically for SMEs’ performance (Ferreira et al. 2021). The finding implies that firms with a greater EO could generate better performance and reinforces that managers need to adopt an entrepreneurial approach to looking for solutions that will help them to achieve their goals (Susanto et al. 2023).

Finally, regarding the role of EO in the relationship between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance, a partial mediation effect was found, thus supporting Hypothesis 4. This result suggests that the deployment of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities is associated with firm performance both directly and indirectly via EO, confirming the importance of mechanisms such as those that meta-analyses have revealed (Bitencourt et al. 2020; Fainshmidt et al. 2016; Karna et al. 2016; Pezeshkan et al. 2016). However, unlike previous works centered on how changes in resource endowments partially mediate that link, ours is the first study confirming the relevance of EO. This result reveals that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and EO are not different ways to manage an uncertain environment, but factors that operate in tandem, or in other words, that EO helps firms to avoid the possible dysfunctional side of dynamic capabilities, understood as core capabilities (Leonard-Barton 1992).

This is a critical finding if we consider “how important it is for SMEs to adapt to rapidly changing market conditions while operating with scarce resources” (Limaj and Bernroider 2019, p. 138). In addition, this result is consistent with the idea that a company must be able to steadily incorporate new knowledge to improve future entrepreneurial initiatives and, ultimately, firm performance (Wales et al. 2021). It is also consistent with the argument that “EO helps complete the processes of knowledge generation, knowledge utilization, and value realization” (Zhu et al. 2019, p. 5), and acts as a partial mediator between knowledge-related capabilities, such as organizational learning capability (Aragón-Correa et al. 2007) or absorptive capacity (a particular type of dynamic capability) (Chaudhary and Batra 2018) and firm performance. Our findings thus confirm that the relationship between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and firm performance is nuanced rather than a simple direct association (Hernández-Linares et al. 2021). From a practical point of view, this result implies that managers of SMEs need to be able to combine different complex tools (such as knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and an EO) to improve their companies’ performance, highlighting the critical role of well trained and experienced managers.

6 Conclusions

6.1 Contributions to literature

We contribute to the dynamic capabilities’ literature in five main ways. First, we shed light on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm performance (Hernández-Linares et al. 2021; Pezeshkan et al. 2016), which has been described as an insufficiently explored topic (Schilke et al. 2018). Specifically, our study found that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities are associated with firm performance in the Iberian SMEs context, emphasizing the importance of knowledge management capabilities to face resource constraints and promote sustainable SMEs.

Second, we address the call to consider possible mediator effects in the relationship between a firm’s dynamic capabilities and its performance (Schilke et al. 2018) by revealing that EO partially mediates this relationship in such a way that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities influence firm performance both directly and indirectly via EO. This is an important contribution because until the present, studies exploring the mediating mechanisms in the dynamic capabilities-performance link have mainly focused on the mediating role of changes in resources set (Schilke et al. 2018).

Third, we help to broaden our knowledge on the role of strategic orientations in the relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm performance, since until now such orientations have been investigated mainly as possible moderators (e.g., Hernández-Linares et al. 2021; Hock-Doepgen et al. 2021). Our study extends Chaudhary and Batra’s (2018) work in two main directions: we consider knowledge-based dynamic capabilities as a general construct (comprising sensing, learning, integrating, and coordinating capabilities) instead of focusing on a particular type of dynamic capabilities and, while Chaudhary and Batra (2018) explore the singular context of small family firms, we focus on the SMEs context.

Since the relationship between EO and its determinants has been under-researched (Arzubiaga et al. 2019), the fourth contribution refers to a better understanding of EO antecedents. Specifically, we focus on the role of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities as a driver to EO (Cope 2005; Dess et al. 2011). Finally, we contribute to business literature by improving knowledge about why some SMEs perform better than others.

6.2 Implications for managers

Considering how our study responds to the two research questions mentioned earlier, several practical implications may be drawn. First, as far as implications for managers are concerned, the value of this research is twofold. Since it is broadly accepted that the success of SMEs largely depends on how they respond to external environments via management capabilities (Do et al. 2022), this article provides guidance on the mechanisms that allow companies to improve their firm performance with dynamic tools. The results are useful for managers of SMEs in terms of the positive influence that the development of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities can have for firm performance to face change even in contexts with resource constraints. In order to develop these capabilities, SMEs managers are advised to utilize technologies to screen customer data, to develop and implement processes to exchange knowledge with their partners, or to distribute new knowledge among the employees.

Second, our results may also assist managers regarding the potential of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities as a source of improvement for EO. SMEs’ managers may then promote the notion of employees as intraepreneurs, a possibility rendered more operative in the context of these organizations. The small and medium size of those firms facilitates the rapid circulation of ideas, as dynamic capabilities encourage the communication between their employees, which helps to combine diverse views fostering innovation and EO. This requires founders and managers to see their role as one of supporting innovation rather than as one of control. In light of resource scarcity, this needs to be balanced with a pragmatic consideration of existing resources (time, attention, ideas, capital).

Third, our results also offer guidance for managers regarding the value of promoting an EO within the organization, for example, by hiring people with entrepreneurial skills to bring new solutions to the company, or by motivating to the organization’s members to bring entrepreneurial ideas to help the company to promote its goals.

Finally, understanding the relationship between knowledge-based dynamic capabilities, EO, and firm performance can help managers to identify the optimal strategies to configure SMEs’ knowledge-based dynamic capabilities as a key strategic tool to face resource constraints and develop the firm’s EO, which indeed will have a positive effect on performance. When managers recognize the importance of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities, they may cultivate an environment favorable to EO for extracting value from their organization’s knowledge.

6.3 Limitations and opportunities for further research

This study has limitations that signal avenues for further research. First, data about all variables in our model were collected from the same source at a single time, which increases the risks of common method variance. Future studies could collect data about different variables from different sources and/or at different times. Moreover, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow supporting causal explanations. Other causalities are possible (e.g., firms with better performance may have more resources to gain access to external knowledge or to entrepreneurial networks). Therefore, a potential extension of this study would be to employ a longitudinal methodology to empirically explore the dynamics of the processes under analysis. Future studies may also collect data for each organization from several managers—rather than a single one. Second, our data were collected several years ago. However, there are reasons to believe that our primary data remain valuable, in that firms of the Iberian Peninsula (continue to) face an environment that is as complex, uncertain, and dynamic as it was in 2015, in the aftermath of the economic and financial crisis generated by Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. In any event, future studies may retest the hypothesized model using more recent data. More recent developments in the socio-economic and political context may bring new conditions that operate as boundary conditions in our hypothesized model.

Another limitation of our work has to do with the particularities of the empirical setting. The implications of dynamic capabilities may differ in different environments and cultures (Chaudhary and Batra 2018; Chirico and Salvato 2008). Future studies may collect data from SMEs operating in other cultural contexts. In addition, considering that dynamic capabilities may reside in large measure outside of the enterprise’s top management team (Teece 2007), we call for conducting multilevel research that provides a means to explore the micro-foundations of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities.

In addition, our results suggest that the knowledge-based dynamic capabilities constitute a key element to adapt to change. One of the main changes or challenges faced by today’s businesses is digital transformation, and to achieve improved performance based on the digitalization, firms need to combine knowledge on digital technologies with knowledge of digital business models (Bouncken et al. 2021). We therefore call for further research about the role of dynamic capabilities in the process of integration of digital technologies in SMEs.

6.4 Short concluding note

In light of increasing environmental uncertainty, dynamic capabilities have attracted growing attention (Dejardin et al. 2023; Fabrizio et al. 2022; Schilke et al. 2018) and “[their study] has grown into one of the central streams in current strategy research” (Schriber and Löwstedt 2020, p. 377). Our study joins those of dynamic capabilities scholars who are now starting to explore the causal mechanisms, such as the mediators (Schilke et al. 2018) of the relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm performance, revealing that knowledge-based dynamic capabilities contribute to firm performance directly and indirectly via EO. By revealing the triggering role of an EO in energizing dynamization of dynamic capabilities we help to explain the mechanisms of organizational renewal in the face of changing environments.

Notes

Provisional data from the Structural Business Statistics (SBS) of Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sbs_sc_ovw/default/table?lang=en).

References

Álvarez SA, Barney JB (2007) Discovery and creation: alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strateg Entrep J 1(1–2):11–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.4

Aragón-Correa JA, García-Morales VJ, Cordón-Pozo E (2007) Leadership and organizational learning’s role on innovation and performance: lessons from Spain. Ind Mark Manag 36(3):349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.09.006

Arend RJ (2014) Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: how firm age and size affect the ‘capability enhancement–SME performance’ relationship. Small Bus Econ 42(1):33–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9461-9

Arend RJ, Bromiley P (2009) Assessing the dynamic capabilities view: spare change, everyone. Strateg Organ 7(1):75–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127008100132

Arzubiaga U, Maseda A, Iturralde T (2019) Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: new drivers and the moderating role of the strategic involvement of the board. Aust J Manag 44(1):128–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896218780949

Atukeren E, Korkmaz T, Çevik Eİ (2013) Spillovers between business confidence and stock returns in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Int J Finance Econ 18(3):205–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1453

Augier M, Teece DJ (2009) Dynamic capabilities and the role of managers in business strategy and economic performance. Organ Sci 20(2):410–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0424

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research—conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51(6):1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Barringer BR, Bluedorn AC (1999) The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strateg Manag J 20(5):421–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199905)20:5%3c421::AID-SMJ30%3e3.0.CO;2-O

Bitencourt CC, de Oliveira Santini F, Ladeira WJ, Santos AC, Teixeira EK (2020) The extended dynamic capabilities model: a meta-analysis. Eur Manag J 38(1):108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.04.007

Bouncken RB, Kraus S, Roig-Tierno N (2021) Knowledge-and innovation-based business models for future growth: digitalized business models and portfolio considerations. Rev Manag Sci 15(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00366-z

Caloghirou Y, Kastelli I, Tsakanikas A (2004) Internal capabilities and external knowledge sources: Complements or substitutes for innovative performance? Technovation 24(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00051-2

Chaudhary S, Batra S (2018) Absorptive capacity and small family firm performance: exploring the mediation processes. J Knowl Manag 22(6):1201–1216. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2017-0047

Chien SY, Tsai CH (2012) Dynamic capability, knowledge, learning, and firm performance. J Organ Change Manag 25(3):434–444. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811211228148

Chien SY, Tsai CH (2021) Entrepreneurial orientation, learning, and store performance of restaurant: the role of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities. J Hosp Tour Manag 46:384–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.007

Chirico F, Salvato C (2008) Knowledge integration and dynamic organisational adaptation in family firms. Fam Bus Rev 21(2):169–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00117.x

Colombo MG, Piva E, Quas A, Rossi-Lamastra C (2020) Dynamic capabilities and high-tech entrepreneurial ventures’ performance in the aftermath of an environmental jolt. Long Range Plann 54(3):102026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2020.102026

Cope J (2005) Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 29(4):373–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00090.x

Cosenz F, Bivona E (2021) Fostering growth patterns of SMEs through business model innovation. A tailored dynamic business modelling approach. J Bus Res 130:658–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.003

Cossío-Silva FJ, Vega-Vázquez M, Revilla-Camacho MÁ (2015) The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on results: an application to the hotel sector. In: Peris-Ortiz M, Sahut JM (eds) New challenges in entrepreneurship and finance. Springer, Cham, pp 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08888-4_8

Covin JG, Garrett RP, Kuratko DF, Bolinger M (2021) Internal corporate venture planning autonomy, strategic evolution, and venture performance. Small Bus Econ 56(1):293–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00220-2

Danneels E (2015) Survey measures of first- and second-order competences. Strateg Manag J 37(10):2174–2188. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2428

De Massis A, Kotlar J, Mazzola P, Minola T, Sciascia S (2018) Conflicting selves: family owners’ multiple goals and self-control agency problems in private firms. Entrep Theory Pract 42(3):362–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12257

Dejardin M, Raposo ML, Ferreira JJ, Fernandes CI, Veiga PM, Farinha L (2023) The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME performance during COVID-19. Rev Manag Sci 17:1703–1729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00569-x

Denford JS (2013) Building knowledge: developing a knowledge-based dynamic capabilities typology. J Knowl Manag 17(2):175–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271311315150

Dess GG, Pinkham BC, Yang H (2011) Entrepreneurial orientation: assessing the construct’s validity and addressing some of its implications for research in the areas of family business and organizational learning. Entrep Theory Pract 35(5):1077–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00480.x

Di Stefano G, Peteraf M, Verona G (2014) The organizational drivetrain: a road to integration of dynamic capabilities research. Acad Manag Perspect 28(4):307–327. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0100

Dias C, Gouveia Rodrigues R, Ferreira JJ (2021) Small agricultural businesses’ performance—What is the role of dynamic capabilities, entrepreneurial orientation, and environmental sustainability commitment? Bus Strategy Environ 30:1898–1912. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2723

Do H, Budhwar P, Shipton H, Nguyen HD, Nguyen B (2022) Building organizational resilience, innovation through resource-based management initiatives, organizational learning and environmental dynamism. J Bus Res 141:808–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.090

Dorfleitner G, Nguyen QA (2022) Mobile money for women’s economic empowerment: the mediating role of financial management practices. Rev Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00564-2

Dushnitsky G, Lenox M (2006) When does corporate venture capital investment create firm value? J Bus Ventur 21(6):753–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.012

Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA (2000) Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg Manag J 21(10–11):1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11%3c1105::AID-SMJ133%3e3.0.CO;2-E

Engelen A, Kube H, Schmidt S, Flatten TC (2014) Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: the moderating role of absorptive capacity. Res Policy 43(8):1353–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.03.002

Eriksson T (2014) Processes, antecedents and outcomes of dynamic capabilities. Scand J Manag 30(1):65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2013.05.001

Fabrizio CM, Kaczam F, de Moura GL, da Silva LSCV, da Silva WV, da Veiga CP (2022) Competitive advantage and dynamic capability in small and medium-sized enterprises: a systematic literature review and future research directions. Rev Manag Sci 16(3):617–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00459-8

Faccin K, Balestrin A, Volkmer Martins B, Bitencourt CC (2019) Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities: a joint R&D project in the French semiconductor industry. J Knowl Manag 23(3):439–465. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2018-0233

Fainshmidt S, Pezeshkan A, Lance Frazier M, Nair A, Markowski E (2016) Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: a meta-analytic evaluation and extension. J Manag Stud 53(8):1348–1380. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12213

Ferreira JJ, Fernandes CI, Kraus S, McDowell WC (2021) Moderating influences on the entrepreneurial orientation-business performance relationship in SMEs. Int J Entrep Innov 22(4):240–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/14657503211018109

Floyd SW, Lane PJ (2000) Strategizing throughout the organization: managing role conflict in strategic renewal. Acad Manag Rev 25(1):154–177. https://doi.org/10.2307/259268

García Calavia MÁ, Rigby M (2020) The extension of collective agreements in France, Portugal and Spain. Transf Eur Rev Labour Res 26(4):399–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258920970131

Green KM, Covin JG, Slevin DP (2008) Exploring the relationship between strategic reactiveness and entrepreneurial orientation: the role of structure style fit. J Bus Ventur 23(3):356–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2007.01.002

Gunawan T, Jacob J, Duysters G (2016) Network ties and entrepreneurial orientation: innovative performance of SMEs in a developing country. Int Entrep Manag J 12(2):575–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0355-y

Hair JFJ, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006) Multivariate data analysis, 6th edn. Pearson Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River

Hair JFJ, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Harman HH (1967) Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hayes AF (2018) Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr 85(1):4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Hayes AF, Little TD (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Methodology in the social sciences. The Guilford Press, New York

Heider A, Gerken M, van Dinther N, Hülsbeck M (2021) Business model innovation through dynamic capabilities in small and medium enterprises—evidence from the German Mittelstand. J Bus Res 130:635–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.051

Heidt L, Gauger F, Pfnür A (2022) Work from home success: agile work characteristics and the mediating effect of supportive HRM. Rev Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00545-5

Helfat CE, Martin JA (2015) Dynamic managerial capabilities: a perspective on the relationship between managers, creativity, and innovation in organizations. In: Shalley CE, Hitt MA, Zhou J (eds) The Oxford handbook of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 421–429

Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2015) Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg Manag J 36(6):831–850. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2247

Hernández-Linares R, Kellermanns FW, López-Fernández MC (2018) A note on the relationships between learning, market, and entrepreneurial orientations in family and nonfamily firms. J Fam Bus Strateg 9(3):192–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2018.08.001

Hernández-Linares R, Kellermanns FW, López-Fernández MC, Sarkar S (2020) The effect of socioemotional wealth on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and family business performance. BRQ Bus Res Q 23(3):174–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/2340944420941438

Hernández-Linares R, Kellermanns FW, López-Fernández MC (2021) Dynamic capabilities and SME performance: the moderating effect of market orientation. J Small Bus Manag 59(1):162–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12474

Hock-Doepgen M, Clauss T, Kraus S, Cheng CF (2021) Knowledge management capabilities and organizational risk-taking for business model innovation in SMEs. J Bus Res 130:683–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.001

Hoffman CC, Nathan BR, Holden LM (1991) A comparison of validation criteria: objective versus subjective performance measures and self-versus supervisor ratings. Pers Psychol 44(3):601–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb02405.x

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behavior, institutions, and organizations across nations, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Hughes M, Morgan RE (2007) Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Ind Mark Manag 36(5):651–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.04.003

Hughes M, Hughes P, Hodgkinson I, Chang YY, Chang CY (2022) Knowledge-based theory, entrepreneurial orientation, stakeholder engagement, and firm performance. Strateg Entrep J16(3):633–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1409

Iyer KN, Srivastava P, Srinivasan M (2019) Performance implications of lean in supply chains: exploring the role of learning orientation and relational resources. Int J Prod Econ 216:94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.04.012

Kallmuenzer A, Strobl A, Peters M (2018) Tweaking the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in family firms: the effect of control mechanisms and family-related goals. Rev Manag Sci 12:855–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0231-6

Karna A, Richter A, Riesenkampff E (2016) Revisiting the role of the environment in the capabilities–financial performance relationship: a meta-analysis. Strateg Manag J 37(6):1154–1173. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2379

Kohli AK, Shervani TA, Challagalla GN (1998) Learning and performance orientation of salespeople: the role of supervisors. J Mark Res 35(2):263–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379803500211

Kreiser PM (2011) Entrepreneurial orientation and organizational learning: the impact of network range and network closure. Entrep Theory Pract 35(5):1025–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00449.x

Kurtmollaiev S (2020) Dynamic capabilities and where to find them. J Manag Inq 29(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617730126

Kyrgidou LP, Spyropoulou S (2013) Drivers and performance outcomes of innovativeness: an empirical study. Br J Manag 24(3):281–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00803.x

Leonard-Barton D (1992) Core capabilities and core rigidities: a paradox in managing new product development. Strateg Manag J 13(S1):111–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250131009

Liao J, Welsch H, Stoica M (2003) Organizational absorptive capacity and responsiveness: an empirical investigation of growth-oriented SMEs. Entrep Theory Pract 28(1):63–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.00032

Limaj E, Bernroider EW (2019) The roles of absorptive capacity and cultural balance for exploratory and exploitative innovation in SMEs. J Bus Res 94:137–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.052

Linz J (1979) Europe’s Southern frontier: Evolving trends toward what? Daedalus 108(1):175–209

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (1996) Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad Manag Rev 21(1):135–172. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9602161568

Lumpkin GT, Brigham KH, Moss TW (2010) Long-term orientation: implications for the entrepreneurial orientation and performance of family businesses. Entrep Reg Dev 22(3–4):241–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985621003726218

Makadok R (2001) Toward a synthesis of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views of rent. Strateg Manag J 22(5):387–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.158

Margaça C, Hernández-Sánchez BR, Cardella GM, Sánchez-García JC (2021) Impact of the optimistic perspective on the intention to create social enterprises: a comparative study between Portugal and Spain. Front Psychol 12(12):680751. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680751

Medeiros V, Marques C, Galvão AR, Braga V (2020) Innovation and entrepreneurship as drivers of economic development: differences in European economies based on quadruple helix model. Competitiv Rev 30(5):681–704. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-08-2019-0076

Menéndez Pujadas A, Gorris Costa A, Dejuán Bitria B (2017) Economic and financial performance of Spanish non-financial corporations during the economic crisis and the first years of recovery: a comparative analysis with the euro area. Econ Bull 11:17

Miao C, Coombs JE, Qian S, Sirmon DG (2017) The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation: a meta-analysis of resource orchestration and cultural contingencies. J Bus Res 77:68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.016

Miller D (1992) The Icarus paradox: how exceptional companies bring about their own downfall. Bus Horiz 35(1):24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(92)90112-M

Morgan N, Vorhies D, Mason C (2009) Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strateg Manag J 30(8):909–920. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.764

Morris MH, Kuratko DF, Covin JG (2011) Corporate entrepreneurship and innovation. Cengage/South-Western, Mason

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) The Schumpeterian tradeoff revisited. Am Econ Rev 72(1):114–132

Neves ME, Proença C, Dias A (2020) Bank profitability and efficiency in Portugal and Spain: a non-linearity approach. J Risk Financ Mana 13(11):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13110284

Ngai JCH, Ellis P (1998) Market orientation and business performance: some evidence from Hong Kong. Int Mark Rev 15(2):119–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339810212502

Ngo M, Mustafa MJ, Butt MM (2022) When and why employees take charge in the workplace: the roles of learning goal orientation, role-breadth self-efficacy and co-worker support. Rev Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00568-y

Nieves J, Haller S (2014) Building dynamic capabilities through knowledge resources. Tour Manag 40:224–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.010

Obeso M, Hernández-Linares R, López-Fernández MC, Serrano-Bedia AM (2020) Knowledge management processes and organizational performance: the mediating role of organizational learning. J Knowl Manag 24(8):1859–1880. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2019-0553

O’Connor NG, Deng FJ, Fei P (2015) Observability and subjective performance measurement. Abacus 51(2):208–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12050

Pavlou PA, El Sawy OA (2011) Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decis Sci 42(1):239–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00287.x

Peteraf M, Di Stefano G, Verona G (2013) The elephant in the room of dynamic capabilities: bringing two diverging conversations together. Strateg Manag J 34(12):1389–1410. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2078

Pezeshkan A, Fainshmidt S, Nair A, Lance Frazier M, Markowski E (2016) An empirical assessment of the dynamic capabilities–performance relationship. J Bus Res 69(8):2950–2956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.152