Abstract

Organizational citizenship behavior is a highly sought-after outcome. We integrate insight from the psychological ownership perspective and agency theory to examine how the juxtaposition of informal psychological mechanisms (i.e., ownership feelings toward an organization) and formal and informal governance mechanisms (i.e., employee share ownership, agency monitoring, and peer monitoring) influences employees' organizational citizenship behaviors. Our empirical results show that psychological ownership has a positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior. Contrary to the common belief that informal and formal mechanisms complement each other, we find that the positive influence of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior is more pronounced when employee share ownership and agency monitoring is low compared to high. Implications for theory and future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Agency theory suggests that one of the biggest challenges of an organization is to forgo employees’ self-interest and motivate them to act in the best interests of the organization. It specifically assumes that unless individuals have formal ownership, they tend to prioritize their self-interests (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Hence, agency theory predicts that by curbing employees’ self-interested behaviors through governance mechanisms, organizations can better achieve their goals (Aluchna and Kuszewski 2021; McConville et al. 2016; Alchian and Demsetz 1972). Some predictions of agency theory, however, have been challenged (Bosse and Phillips 2016; Madison et al. 2017). Proponents of the psychological ownership perspective contradict agency theory by suggesting that ownership feelings in organizations and their consequent positive work behaviors can be induced without formal ownership (Zhang et al. 2021; Pierce et al. 2001; Van Dyne and Pierce 2004; Hernandez 2012). Furthermore, despite their enormous implementation costs, governance mechanisms have failed to result in unanimous positive organizational outcomes (Loughry and Tosi 2008; Sieger et al. 2013; Pierce and Rodgers 2004). In addition, the emphasis of governance mechanisms has predominantly focused on curbing employees’ negative behaviors, such that their impact on employees’ positive behaviors has been undermined.

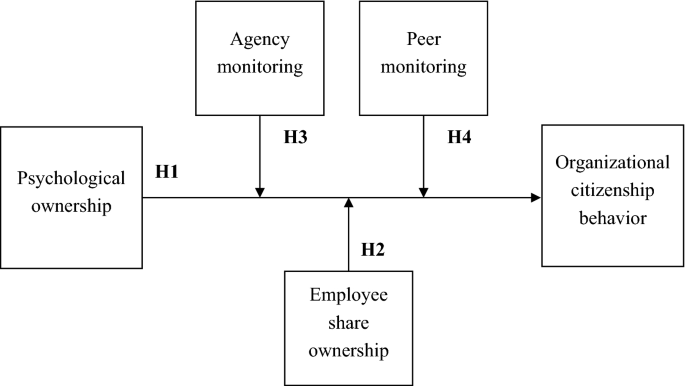

To better understand the impact of agency mechanisms, scholars have called for research integrating agency theory and other perspectives, specifically the psychological ownership theory (Chi and Han 2008; Sieger et al. 2013). Although these theories focus on similar outcomes (i.e., how to induce employee behaviors aligned with organizational goals), their underlying mechanisms are different. For the most part, agency theory emphasizes a formal (hard) approach centered on organizational interventions that trigger extrinsic motivation (e.g., Bratfisch et al. 2023). In contrast, psychological ownership is geared toward an informal (soft) perspective that stimulates employees’ intrinsic motivation to act in the organization’s best interest (e.g., Sieger et al. 2013). Instead of being examined in isolation, these theories may be juxtaposed because the soft and hard elements underlying these theories coexist in organizations and impact each other (Pesch et al. 2021; Sieger et al. 2013; LePine et al. 2002; Wagner et al. 2003). To address the shortcomings in the literature, we integrate these two theories to examine how psychological ownership influences organizational citizenship behavior and how governance mechanisms, including employee share ownership, agency monitoring, and peer monitoring, bound the relationship between informal psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior? To address these research questions, we propose a set of hypotheses and empirically test them with primary survey data from 324 employees in two architectural, engineering, and surveying organizations in the United States.

We make four theoretical contributions: First, by juxtaposing the assumptions of psychological ownership and agency theories regarding human motivation and behaviors in organizations, we show how the coexistence of ownership feelings and governance mechanisms (employee share ownership, etc.) impacts employees’ extra-role behaviors. Although the direct relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior has been studied before (e.g., Zhang et al. 2021; O’Driscoll et al. 2006; Vandewalle et al. 1995), our work goes beyond by advancing the theory about interventions with formal and informal governance mechanisms to induce, maintain, and nurture the relationship between ownership feelings and citizenship behaviors (Aluchna and Kuszewski 2021; Wagner et al. 2003; Buchko 1993). This further enables us to contribute to the sparse research stream that challenges the prevailing assumptions about the effect of extrinsic motivators on intrinsic ones by showing that not all extrinsic incentives necessarily reduce the positive impact of intrinsic motivators. Instead, attention should be paid to more fine-grained characteristics of extrinsic motivators, such as whether they are implemented through formal or informal organizational procedures. Second, we contribute to agency theory (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976) by moving beyond past research's common emphasis on how governance mechanisms enhance organizational and financial performance under the assumption of minimizing employees’ negative, calculative, and self-serving behaviors (Bratfisch et al. 2023; Flammer et al. 2019; Keum 2021; Welbourne et al. 1995). Rather, in this study, we literally examine how governance mechanisms induce and impact employees' cognitive-affective states and behaviors, not in terms of minimizing negative behaviors (past research common assumption) but instead regarding employees' positive and desirable cognitive-affective states and behavioral outcomes. Furthermore, contrary to past organizational governance research that has mainly relied on archival data (Daily et al. 2003), our work relies on primary survey data from two organizations to provide possible answers to why different governance mechanisms may not always bring about the expected outcomes (Basterretxea and Storey 2018); hence, increasing the predictive validity of agency theory. Third, we contribute to the literature on employee ownership (e.g., Poutsma et al. 2006) by examining its dual facets (psychological and formal) together. This sets our work apart from past studies that investigate the facets of the same concept, employee ownership, exclusively and in isolation from each other as if they do not exist simultaneously in an organization (Buchko 1993; O’Boyle et al. 2016); hence, our work promises results with higher rigor and validity. Our findings show that formal and psychological ownership coexistence does not create a positive synergistic influence on citizenship behaviors. Fourth, our research contributes to the theory about monitoring as a governance mechanism (e.g., Sieger et al. 2013; Wagner et al. 2003) by uncovering different types of monitoring, agency (supervisor) monitoring vs. peer monitoring, each having different implications for employees' ownership feelings and extra-role behaviors. In doing so, we have examined the under-studied construct of peer monitoring as an independent governance mechanism, in contrast to past research that had predominantly considered it as the aftermath of employee profit-sharing plans and collaborative outcomes in organizations (Core and Guay 2001; Bolduan et al. 2021). Our findings suggest that peer monitoring may have other unexplored faces and that it may not necessarily fit in with other governance mechanisms that are predominantly preventive in nature.

2 Theoretical framework

Our theoretical model is summarized in Fig. 1. As we will outline in more detail below, we will argue that the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior is moderated by three factors. Specifically, we focus on employee share ownership, agency monitoring, and peer monitoring.

2.1 Agency theory

Agency theory, a dominant paradigm in management theorizing, has been applied extensively across various research disciplines, such as organizational behavior (e.g., Larkin et al. 2012; Buchko 1993), strategic management (e.g., Shi et al. 2016; Perryman and Combs 2012), family business (e.g., Eddleston et al. 2018; Madison et al. 2017), and entrepreneurship (e.g., Bratfisch et al. 2023). It examines the relationship between principals (e.g., owners) and agents (e.g., employees), whereby the principal engages the agent to perform certain services and to make decisions on the principal’s behalf (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Davis et al. 1997).

According to agency theory, agents are assumed to be self-interested, rational, profit-maximizing individuals whose interests are incongruent with those of principals (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976). As a result, agents’ actions and decisions may not be consistent with principals’ desires for long-term profit maximization and organizational growth. Agents can hide their (undesirable) intentions from principals due to information asymmetry. Ex-ante this may lead to adverse selection and ex-post to moral hazard (Eisenhardt 1989).

To align principals’ and agents’ interests, principals often use corporate governance mechanisms, including incentives (e.g., employee share ownership plans) and monitoring (e.g., formal and informal employee job assessments) (Chrisman et al. 2007; Ang et al. 2000; Nyberg et al. 2010). Research suggests that such mechanisms encourage agents to act and make decisions in line with organizational objectives because, under such circumstances, their interests will correlate with those of principals (Eisenhardt 1989; Chrisman et al. 2007; Madison et al. 2017). However, according to scholars who have challenged this view, formal governance mechanisms may not inherently lead to agents’ behavioral changes (Pierce and Furo 1990), especially when these mechanisms intertwine with psychological elements, such as individuals’ ownership feelings toward an organization (Pierce et al. 2001).

Prior research suggests that formal mechanisms, in addition to agents’ psychological states, impact their behaviors (Zhang et al. 2021; Buchko 1993). However, because these concepts have mainly been investigated separately, it remains unclear if they are effective in combination and whether different formal mechanisms positively or negatively change the impact of psychological ownership on employees’ work behaviors (Liu et al. 2019). In light of these shortcomings in the prevailing literature, we examine how psychological ownership shapes employees’ organizational citizenship behavior toward their organization and how governance mechanisms prescribed by agency theory—employee share ownership plans, agency monitoring, and peer monitoring—moderate our proposed baseline relationship.

2.2 The influence of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior

Organizational citizenship behavior, defined as “contributions in the workplace that go beyond role requirements and contractually rewarded job achievements” (Organ and Ryan 1995, p. 775), is a lubricant for “the social machinery of the organization” (Podsakoff et al. 1997, p. 263). As a highly sought-after outcome, true organizational effectiveness is achieved when employees willingly engage in extra-role behaviors that exceed their formal job descriptions to help the organization achieve its goals in response to various contingencies (Motowidlo and Van Scotter 1994). Organizational citizenship behavior is especially relevant here because, as a contextual performance variable, it demonstrates the extent to which organizations can influence employees’ positive behaviors (Organ and Ryan 1995).

In line with prior literature (e.g., Van Dyne and Pierce 2004; Liu and Wang 2013), we expect that there will be a positive relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. Prior research suggests that ownership feelings induce positive emotions in employees by meeting their need for belonging, which positively impacts their willingness to contribute to the organization beyond their formal roles (Beggan 1992). When employees feel that they belong to the organization, they view the organization as an extension of themselves over which they can exert control; that is, the organization becomes part of their self-concept and self-identity (Belk 1988). To boost their self-concept, employees who identify with their organization feel more responsible for the organization and its outcomes, which encourages them to engage in proactive extra-role behaviors that will elevate the organization’s well-being (Van Dyne and Pierce 2004; Liu and Wang 2013; Pierce et al. 2001).

Individuals who feel that they own something valuable tend to feel protective and proud of the target of their ownership (Vandewalle et al. 1995). Ownership feelings trigger protective behaviors in employees not only to maintain the target of ownership but to enhance its future status. Employees with ownership feelings are more likely to exhibit voluntary extra-role behaviors that will improve important organizational outcomes, even if this requires them to go above and beyond their formal responsibilities (Van Dyne and Pierce 2004).

When employees perceive that they can meet their need for belonging and effectance through the organization, they become motivated to give back to the organization voluntarily. Although these volitional actions are not necessarily rewarded through formal organizational processes, employees engage in them because they perceive that the organization is attentive to and considerate of their needs (Dawkins et al. 2017).

Taken together, we expect that psychological ownership positively impacts employees’ organizational citizenship behavior through three explanatory mechanisms. First, psychological ownership feelings lead to the satisfaction of the need to belong and the nurturing of self-concept. Second, the satisfaction that employees perceive as a result of meeting their need to belong triggers their reciprocating behaviors to satisfy the organization’s needs and enhance its outcomes. Third, feelings of ownership are associated with strong tendencies and behaviors that will protect the target of ownership from harm and boost its image and performance. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1

Employees’ psychological ownership feelings toward their organization are positively related to their organizational citizenship behaviors.

Although the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior has been examined, the findings have been inconsistent. For instance, in most studies, a positive relationship has been established between the two constructs (e.g., Pierce et al. 2001; Van Dyne and Pierce 2004), while others have not found a significant relationship (Liu et al. 2012; O’Driscoll et al. 2006). Hence, it is likely that this relationship depends much on boundary conditions. To provide more clarity, we examine whether the governance mechanisms prescribed by agency theory (employee share ownership, agency monitoring, and peer monitoring) moderate the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. We discuss each contingency separately below.

2.3 The moderating effect of employee share ownership

To curb employees’ opportunistic behaviors, organizations implement employee share ownership plans, which give equity (shares) to employees to better motivate them to work toward organizational goals (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Poutsma et al. 2006). While some have found employee share ownership to have a positive impact on employees’ desirable intentions, behaviors, and, ultimately, performance (Guery 2015; Whitfield et al. 2017), the results have been inconsistent (Long 1978; McCarthy et al. 2010), indicating that in addition to formal ownership, the feelings of informal ownership may be at play to impact the desired employee behaviors in organizations. So, what happens when psychological ownership and employee share ownership coexist in an organization?

Past research regarding the coexistence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators in organizations follows a dualistic logic: According to the proponents of the "diminishing" view, extrinsic motivators diminish the positive impact of intrinsic motivators (Grant 2008; Deci 1971). They argue that extrinsic motivators are more tangible, conspicuous, and noticeable (Kuvaas et al. 2017); hence, in competition with intrinsic motivators, they attract a larger share of employees' limited attention; therefore, intrinsic motivators lose their impact on individuals' perceptions and behaviors at the presence of extrinsic motivators (Lindenberg and Foss 2011; Gagné and Deci 2005; Sue-Chan and Hempel 2016). On the other hand, the advocates of the newly emerged "additive" perspective argue that extrinsic motivators do not always diminish intrinsic motivators but may actually support and amplify the intrinsic motivators' positive impact on desired behaviors (Frey 1997; Osterloh and Frey 2000). This line of research builds on the assumption that extrinsic motivators hurt the positive impact of intrinsic motivators only when they trigger employees to shift their locus of control from internal to external (Deci 1975). Otherwise, employees may perceive extrinsic motivators in ways that strengthen the positive impact of intrinsic motivators with which they overlap; for instance, if they perceive the extrinsic motivator to be associated with a positive public image or desirable social goal (Bruni et al. 2020; Frey 1997). Therefore, their findings suggest that the diminishing view of extrinsic motivators does not apply to all situations in organizations.

Similarly, it is possible to theoretically identify the tracks of both additive and diminishing effects of governance mechanisms that are predominantly extrinsically motivating on employees' behaviors. Being a shareholder and an employee could enhance employees’ perceptions of their influence and control over the organization and its outcomes, leading them to feel like an owner, hence, strengthening the relationship between their feelings of psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. The motivational power of formal ownership encourages employees to see the organization as part of themselves and perceive their interests intertwined with that of the organization and other shareholders, hence, feeling a higher sense of belonging (Buchko 1993; Van Dyne and Pierce 2004). In addition, employee share ownership may convey to employees that their contributions to the long-term organization's success are desired, valued, and recognized (Long 1980).

On the other hand, employee share ownership may neutralize or diminish the positive outcomes of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior. If employees do not associate employee share ownership with increased influence and control over the organization, they may consider them ineffective and superficial (Freeman et al. 2010). Furthermore, employee share ownership may harbor perceptions of unfairness if they are not distributed based on objective performance and merit criteria (Hansmann 1996). In addition, when granted to employees with high psychological ownership, employees' formal ownership may become redundant (Kuvaas et al. 2017); therefore, diminishing the marginal positive effect of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior because employees high in psychological ownership are already intrinsically motivated to strive for the best possible organizational outcomes (Sieger et al. 2013).

In sum, we expect the diminishing effect of employee share ownership to be stronger than its additive effect. We reason that between the two competing influences, the diminishing effect will be more salient to employees because it may bring up a comparison of their performance with peers; hence, it harbors perceptions of unfair distribution criteria and treatment (Bakan et al. 2004; Bruni et al. 2020; Sengupta et al. 2007). Therefore, it is more reasonable to anticipate the employee share ownership plans to weaken the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behaviors. Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2

Employee share ownership moderates the relationship between employee psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. The positive influence of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior is stronger when employee share ownership is low compared to high.

2.4 The moderating effect of agency monitoring

Establishing alignment between managers’ and employees’ interests can be achieved through organizational control systems, which seek to coordinate employees’ behaviors and organizational goals through incentives and monitoring (Tosi et al. 1997). Agency monitoring consists of supervisors observing employees’ behaviors and outcomes through surveillance, codified policies, and rules to ensure agents’ conformity with organizational goals (Kreutzer et al. 2016). According to agency theory, employees tend to shirk their job responsibilities if their behaviors are left unmonitored (Conlon and Parks 1990). Therefore, in agency monitoring, a formal control mechanism, managers monitor employee behaviors and outputs relative to a set of agreed-upon policies and procedures that tend to clarify their organizational roles in hopes of reducing employees’ shirking behaviors (Pesch et al. 2021; Fong and Tosi 2007; Alchian and Demsetz 1972).

We expect that the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior is contingent on the level of agency monitoring. As an extrinsic motivator, agency monitoring is expected to discourage undesirable behaviors, making it more likely for an organization to achieve its goals (Chrisman et al. 2007). It may, however, also diminish the intrinsic motivating effect of psychological ownership on citizenship behaviors.

When agency monitoring is enforced, employees perceive their work environment as more structured with higher formalization, routinization, and more centralized decision making (Fredrickson 1986; Ohly et al. 2006). This leaves less latitude for employees to act on their sense of psychological ownership to exercise discretion in performing their jobs and exert autonomy over the organization through their volitional extra-role behaviors (Maynard et al. 2012; Sieger et al. 2013; Deci and Ryan 2012). Managerial monitoring encourages employees to focus on supervised tasks, usually reflected in employees’ formal job descriptions (Stanton 2000). This discourages employees from engaging in organizational citizenship behavior that originates from psychological ownership.

Implementation of agency monitoring infuses distrust in the relationship between employees and managers, likely triggering employee resistance and other negative attitudes toward the organization (Spitzmüller and Stanton 2006). These negative emotions (Liao and Chun 2016) shatter employees’ feelings of psychological ownership and motivate them to disengage from organizational citizenship behaviors.

Monitoring harms employee psychological well-being, including increased stress, anxiety, anger, and tension (Hartman 1998; Holman et al. 2002). Employees who are constantly monitored experience an ongoing sense of pressure to act based on managers’ expectations (Zhou 2003). This stressful environment encourages conformity (Brown 2000) at the cost of discouraging employees from expressing their psychological ownership through citizenship behaviors.

Overall, we expect low perceived control, diminished sense of trust, and psychological pressures that employees feel due to agency monitoring systems sabotaging the positive emotions associated with psychological ownership and the tendency to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3

Agency monitoring moderates the relationship between employee psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. The positive influence of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior is stronger when agency monitoring is low compared to high.

2.5 The moderating effect of peer monitoring

As an informal control mechanism, peer monitoring aligns the interests of owners and employees through social processes that take place among employees (Glover and Kim 2021). Employees positioned at the same organizational level notice and respond to each other’s task performance (Chrisman et al. 2007), especially when working on inter-related and collective organizational goals (Welbourne et al. 1995). Peer monitoring can extrinsically motivate employees to refrain from opportunistic and shirking behaviors due to the perceived threat of peer sanctions (Li et al. 2017; Loughry and Tosi 2008; Welbourne et al. 1995).

Peer monitoring can trigger cognitive dissonance and frustration in employees with psychological ownership who feel pressured to focus on those tasks noted and monitored by their peers rather than engage in extra-role behaviors that may remain unnoticed or even be sanctioned by peers (De Jong et al. 2014). When peer monitoring is in place, employees feel escalated pressure to act according to their peers’ expectations of appropriate behavior (Feldman 1984; O’Reilly III and Caldwell 1985; Sewell 1998). Like agency monitoring this creates a stress-infused working climate that diminishes psychological ownership and encourages employee conformity with social and group expectations to gain their peers’ social approval (Loughry and Tosi 2008; Aubé et al. 2009).

Even if we consider the positive connotations of peer monitoring, such as reduced information asymmetry because of enhanced transparency (Palanski et al. 2011; Walter et al. 2021), the reinforcing impact of peer monitoring on employees with psychological ownership is unnecessary because the intrinsic motivation from psychological ownership already enhances their likelihood of engaging in organizational citizenship behaviors. Although we expect only a marginally positive effect of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior under high peer monitoring, it diminishes relative to the same effect under low peer monitoring; high psychological ownership already encourages high organizational citizenship behavior. We expect that under high peer monitoring, the difference in organizational citizenship behavior of employees with low vs. high psychological ownership becomes insubstantial. At high levels of peer monitoring, the organizational citizenship behavior of employees with low psychological ownership becomes more similar to those with high psychological ownership.

In sum, employees' peer pressure to conform to their work group’s social expectations and norms is likely to discourage them from engaging in extra-role behaviors, especially when group norms do not favor such behaviors. Similarly, employees with high psychological ownership may feel tremendous psychological and emotional strain if peer monitoring emphasizes formal job-related behaviors, undermining the exercise of positive discretionary behaviors that other employees may deem appropriate for organizational well-being. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4

Peer monitoring moderates the relationship between employee psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. The positive influence of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior is stronger when peer monitoring is low compared to high.

3 Research method

3.1 Research design and sample

Our sample includes employees of two organizations in the United States that consented to participate in our study and provided us with access to their employees’ email addresses. Both organizations provide professional engineering, architectural, and surveying services to the U.S. domestic construction industry. One firm is headquartered in Michigan, while the other is in Virginia. Both firms have multiple offices and operate independently of one another. Employees of these organizations were allocated company shares upon reaching one year of service while maintaining full-time employment status. The survey instrument was distributed via email with a link to an online questionnaire. Over four weeks, 2,026 emails (an invitation and three reminders) were sent. Removing the responses with missing data resulted in 324 completed surveys (response rate of 16%, which is slightly higher relative to other survey research on psychological ownership and agency systems, e.g., Sieger et al. 2013). Sixty-two percent of respondents were male; the average age was 42.5 years old, and the average tenure was 7.23 years. On average, employees owned 20% of company shares.

3.2 Variables

3.2.1 Dependent variable

3.2.1.1 Organizational citizenship behaviour

We used Lee and Allen’s (2002) 8-item scale to measure the extent to which respondents exhibited organizational citizenship behaviors toward their organization. Responses were measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). All items of this and the other multi-item constructs are displayed in the Appendix.

3.2.2 Independent variables and moderators

3.2.2.1 Psychological ownership

We used Van Dyne and Pierce’s (2004) 7-item scale, which is the measure of choice for psychological ownership (Dawkins et al. 2017). Responses were measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

3.2.2.2 Employee share ownership

This scale reflects indirect ownership of company shares as part of employment benefits (e.g., Poutsma et al. 2006). Employees were asked to specify the approximate value (in dollars) of their shares. To establish normality and to address original values of zero in the variable, the natural log for the variable was taken after 1 was added to the value.

3.2.2.3 Agency monitoring

We used Chrisman and colleagues’ (2007) 5-item scale to examine agency monitoring, which measures the extent to which employees are assessed through monitoring activities, including supervisors’ observation and regular assessment of progress toward short and long-term goals. Responses were measured using a 7-point Likert type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

3.2.2.4 Peer monitoring

We used Welbourne and colleagues’ (1995) 9-item scale to examine the extent to which employees monitored each other’s behaviors and adhered to organizational expectations. Responses were measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

3.2.3 Control variables

We controlled for employees’ age (Basterretxea and Storey 2018), gender, education (Hallock et al. 2004), organizational tenure, and organizational role (Bayo-Moriones and Larraza-Kintana 2009). Gender was a dichotomous variable (1 = male, 0 = female). Two variables represented the respondent’s role within the company: (a) executive and (b) non-executive. Education level included five response choices: (a) some high school, (b) high school diploma, (c) some college, (d) college graduate, and (e) graduate school. Last, we controlled for the organization membership because we sampled from two organizations. While both organizations are part of the same industry and provide similar services, we still wanted to eliminate organizational-level effects on our dependent variable.

4 Results

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables. We utilize ordinary least square (OLS) analysis in our study, as it is the preferred tool to test the moderation effect (Aiken and West 1991). The variables were entered as a block stepwise in each model, beginning with a control-only model (Model 1). The independent variable, the moderators, and the interaction effects were entered in the subsequent three steps. Below, we elaborate on these four models in detail.

To check for common method bias, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Common method bias was not a significant concern because the one-factor model accounted for only 16% of the variance. In confirmatory factor analysis, we allowed the independent, dependent, and moderator variables to load onto one method factor, which showed a very poor fit with χ2 = 3444.07 (405) and a CFI of 0.498, which supports our conclusion (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Furthermore, we need to note that while common method bias may potentially affect mediational models, Evans (1985) has shown that common method bias cannot affect moderation models, as we propose in our study, which further mitigates this concern.

Table 2 reports the OLS regression results of the hypothesized relationships. We regressed organizational citizenship behavior (the dependent variable) on the control variables (Model 1), which explained 14% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior. Second, we included psychological ownership to measure our main effect (Model 2), which significantly increased the explained variance in organizational citizenship behavior (Adjusted R2 = 0.33). Finally, we entered the moderators and the two-way interaction terms (Model 3 and Model 4), with a final adjusted R2 of 0.40.

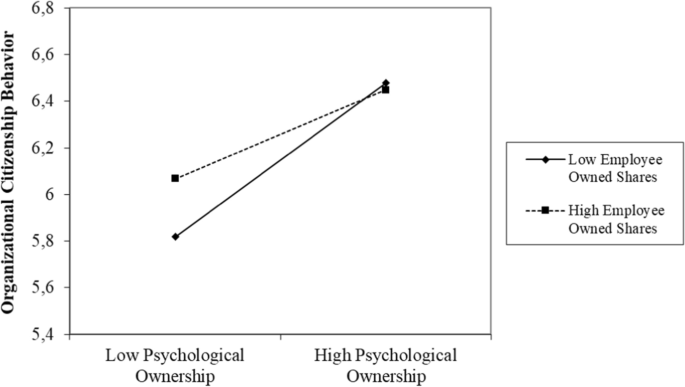

As shown in Model 2, we found support for hypothesis 1, given that the main effect of psychological ownership is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.47, p < 0.001). Regarding hypothesis 2, Model 4 demonstrates that employee share ownership moderates the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior (β = −0.09, p < 0.05). Therefore, our results support hypothesis 2. To interpret this moderating effect, we plotted the interaction relationship. As shown in Fig. 2, when employee share ownership increases, the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior becomes weaker.

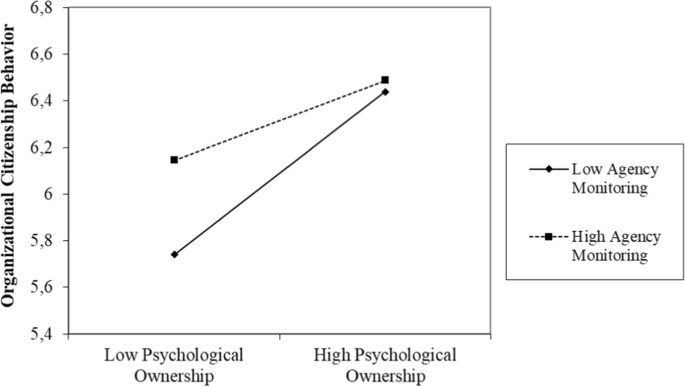

Regarding hypothesis 3, the interaction between psychological ownership and agency monitoring is significant (β = −0.11, p < 0.05). Therefore, we found support for hypothesis 3. As Fig. 3 shows, when agency monitoring increases, the relationship between employee psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior becomes weaker. Our results in Table 2 show that peer monitoring does not moderate the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior (β = −0.002, p = 0.96); hence, we did not find empirical support for hypothesis 4.

In further analysis not reported here, we also checked if the moderation was significant for the moderators' low, medium, and high levels (Hayes 2022). Furthermore, as reported above, the confidence interval around the B value for both significant moderation hypotheses did not contain zero.

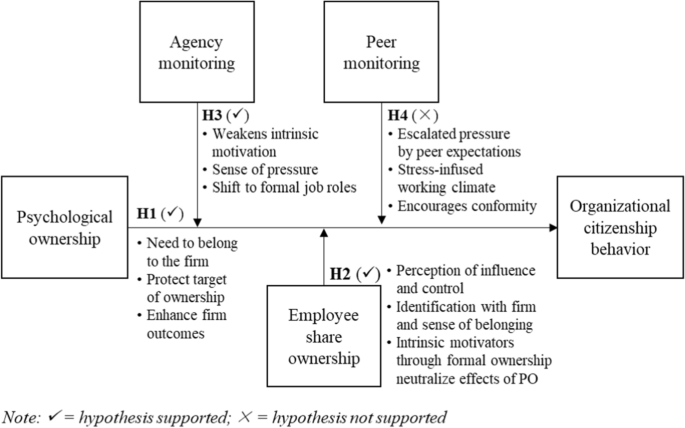

5 Discussion

The focus of this study has been on integrating insights from psychological ownership and agency theory. We drew on empirical survey data to address the following research questions: (1) How does psychological ownership influence organizational citizenship behavior, and (2) how do governance mechanisms, including employee share ownership, agency monitoring, and peer monitoring, serve as boundary conditions? Our results show that psychological ownership positively affects organizational citizenship behavior. Contrary to the common belief that informal and formal mechanisms complement each other, we find that the positive influence of psychological ownership on organizational citizenship behavior is more pronounced when employee share ownership and agency monitoring is low compared to high. Figure 4 portrays the summary of the findings of our research model, which we will discuss in more detail below.

5.1 Theoretical contributions

Our study’s findings contribute to the literature on how organizations can motivate employees to demonstrate positive extra-role behaviors (Dawkins et al. 2017). One well-established path to organizational citizenship behavior is through employees' ownership feelings (Zhang et al. 2021; O’Driscoll et al. 2006; Vandewalle et al. 1995). What gives credence to our research is that employee ownership feelings towards an organization do not exist in a vacuum. Instead, it seems that ownership feelings are intertwined with various formal and informal organizational mechanisms that may impact employees' ownership feelings and subsequent behaviors. To add to the complexity, one should also consider that it is challenging for managers to directly gauge and manipulate employees' cognitive-affective states, such as ownership feelings. Instead, managers have more latitude to enforce governance mechanisms that may implicitly but adversely impact employees' ownership feelings. Therefore, an important piece to this puzzle is how governance mechanisms as important organizational interventions boost or undesirably compromise the positive effect of ownership feelings on employees' extra-role behavior. Compared to past research that has studied the impact of the formal and informal mechanisms in separate studies (e.g., Sieger et al. 2013; Wagner et al. 2003), our research makes an important contribution by examining these mechanisms in the same study. Hence, our work adds to the understanding of governance mechanisms’ impact on employee behaviors. In addition, despite past research positing that these mechanisms impact employee behaviors directly (Hallock et al. 2004; Basterretxea and Storey 2018), we have shown that it is reasonable to consider them as boundary conditions that change the relationship between employees' cognitive-affective states and organizational citizenship behavior (Johns 2006). For instance, our results show that employee share ownership does not have a direct impact on organizational citizenship behavior but an indirect one by influencing the relationship between employees' psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. Hence, our theorizing captures organizational reality more accurately because, in essence, these mechanisms serve as contextual variables that may provide ground for employees' psychological and behavioral manifestations to unfold (Johns 2006). In this sense, our study`s findings contribute to the broader literature on workplace conditions in organizations by showing that the general work environment can have important implications for employees’ behaviors. Considering the insights from recent theoretical advancements, such as the sociomaterial perspective (Leonardi 2012; Orlikowski 2007), our study emphasizes the ability of ownership feelings to influence organizations not only externally (e.g., organizational performance) but also internally. For example, collective psychological ownership feelings among many employees might have the power to transform organizations into a more open and social conversational environment. Such structural conditions, in turn, might enhance identification among employees with the organization and, ultimately, facilitate organizational processes like information flows and behaviors like collaboration (e.g., Aslam et al. 2021; Bouncken et al. 2021).

Regarding agency theory (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976): This perspective posits that governance mechanisms such as employee share ownership effectively curb agents’ (employees’) opportunistic and self-interested behaviors in organizations. However, it overemphasizes governance mechanisms’ preventive impact so that it undermines how these mechanisms impact positive employee states and behaviors (Daily et al. 2003). Surprisingly, from the three governance mechanisms examined, we found a positive and statistically significant direct effect of agency monitoring and peer monitoring as independent variables on organizational citizenship behavior as the dependent variable. Employee share ownership, in turn, did not exert a direct statistically significant relationship on organizational citizenship behavior. This implies that governance mechanisms may influence employees' positive extra-role behaviors, but they do not exert this effect consistently. We conjure that the relational aspect (i.e., interactive nature, etc.) of agency monitoring and peer monitoring may better encourage employees to strive for extra-role behaviors, compared to governance mechanisms that are more procedural, such as employee share ownership that is consistently applied to employees, usually without regard for merit and performance (Hansmann 1996). Our results regarding hypothesis 2 (i.e., employee share ownership plans’ negative moderation effect) indicate that employees' perceptions of employee share ownership plans and its fair distribution may impact how employees' ownership feelings translate into extra-role behaviors. Indeed, per the Employee Retirement Income Security Act in the U.S., organizations cannot treat their employees differently in share distribution if an employee share ownership plan is used. In this sense, employees who meet the employee ownership qualifications join a class of shareholders whereby the method to determine their pro-rata share distribution is equal to all the other participants (in proportion to their salary, tenure, etc.) irrespective of their merit and individual performance (Kim and Ouimet 2014; Beatty 1995). The unfair perceptions that employees may associate with such treatments are likely to weaken identification processes with the organization, which would typically translate their ownership feelings into extra-role behaviors. The perceived unfairness may also diminish employees' sense of belonging, dwindling their willingness to give back to their organization through organizational citizenship behaviors. In addition, employees in share ownership plans are accustomed to being communicated with as an owner, yet they often have no actual managerial responsibilities or decision-making authority resulting from their share ownership; this likely has negative implications for identification processes of employees with the organization, and, as a result, cultural skepticism and distrust among employees might emerge. Our results regarding hypothesis 3 (i.e., the negative moderation effect of agency monitoring) suggest that agency monitoring may undermine ownership feelings' impact on organizational citizenship behavior because it projects hierarchy and separation between employees and ownership; hence, infusing a lack of internal locus of control (Kuvaas et al. 2017; Gagné and Deci 2005; Pierce et al. 2001). It may also trigger employees to question their genuity because ownership usually implies that the owners act in the best interests of the organization, hence, negating a need to be monitored (Sieger et al. 2013; Wagner et al. 2003).

Lastly, we contribute to agency theory by tapping more profoundly into "monitoring" as a governance mechanism by examining agency (supervisor) monitoring (Chrisman et al. 2007) and peer monitoring (Welbourne et al. 1995) as independent constructs. According to our results, peer monitoring does not moderate the relationship between psychological ownership and employee organizational citizenship behavior. We can explain this finding from a few perspectives. Comparing the findings of hypotheses 2 and 3 with hypothesis 4, we suggest that governance mechanisms moderate the relationship between psychological ownership and citizenship behaviors only when these extrinsic motivators are formally implemented in the organization through policies, guidelines, and organization procedures. It is possible that because peer monitoring mostly occurs through informal mechanisms (informal observation, employees’ word of mouth, etc.), it does not possess sufficient power to change the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior compared to other governance mechanisms that are usually implemented through formal mechanisms. Even though peer monitoring has been anecdotally proposed as a governance mechanism to stall self-serving behaviors due to fears induced by peers' sanctions (Li et al. 2017; Loughry and Tosi 2008; Welbourne et al. 1995), it has another aspect that the other two mechanisms lack: It is self-initiated with fewer explicit and extrinsic triggers such as the direct impact on employees' incomes or threat of direct punishment by supervisors; therefore, it better lends itself to employee's interpretations and is more malleable regarding the functions that it serves. For instance, it can become a source of self-assessment and self-regulation (relative to peers). It can also boost the sense of morale among peers because of feedback loops and increased transparency (Mani and Mishra 2020). Therefore, when considered as a governance mechanism tool, peer monitoring should be analyzed with deeper scrutiny as its preventive capacity may be impacted by various roles that it plays in an organization. In addition, the non-significant moderation could result from the nature of the employees' tasks and their level of interdependence in our sample organizations. In other words, it is likely that only in organizations with high employee task interdependence does the moderating effect of peer monitoring become statistically significant (Bolduan et al. 2021). Finally, it is possible to attribute this non-significant relationship to the measurement of the peer monitoring construct in this study. For instance, respondents may not feel sufficient normative pressures at the departmental level, where we measured peer monitoring; hence, peer monitoring may not change the relationship between employees' ownership feeling and their citizenship behaviors.

By and large, one theoretical dilemma that we have tried to resolve comprises the circumstances under which governance mechanisms become less effective in the presence of employees' ownership feelings (Pierce and Furo 1990). One interesting (post-hoc) finding of our research is that at all levels of the two moderators (low, medium, and high), employee share ownership and agency monitoring, the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior becomes weaker. Therefore, our findings regarding the weakening effect of employee share ownership and agency monitoring contribute to and add credence to the ongoing debate (Kuvaas et al. 2017) about the diminishing impact of extrinsic motivators on intrinsic ones (Gagné and Deci 2005; Calder and Staw 1975; Porter and Lawler 1968; Stajkovic and Luthans 2003). Beyond that, we have contributed to the theory by showing that the nature of the governance mechanism, formal vs. informal, may impact the relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior. According to our findings, the informal mechanisms underlying peer monitoring did not change the main relationship between psychological ownership and organizational citizenship behavior.

Furthermore, theoretically and empirically, our knowledge about the coexistence of (informal) ownership feelings and formal ownership in organizations is underdeveloped (Pierce et al. 1991; Chi and Han 2008). Contrary to the common assumptions about the construct of ownership, the logic of “the more, the better” does not apply here. Rather, it is possible that the ownership quality and substance matter more than its quantity. It is also possible that to serve effectively, employees should genuinely perceive themselves as owners because of share ownership plans to feel motivated to go above and beyond their assigned tasks (McConville et al. 2016).

5.2 Practical contributions

Organizations can use our findings to promote organizational citizenship behavior among their employees. We show that the one-size-fits-all approach to governance mechanisms is not effective. When designing the organizational architecture to encourage pro-organizational behaviors, managers should consider the combining effect of employees’ psychological ownership and different governance mechanisms. For instance, implementing employee share ownership or agency monitoring for employees with high psychological ownership can be ineffective. Furthermore, to mitigate the diminishing effect of governance mechanisms on employees' positive psychological attributes and extra-role behaviors, organizations may be able to frame such mechanisms in ways that align with employees' sense of belonging, self-identification with, and control over the organization.

5.3 Limitations and future research

Because the survey was conducted in the commercial engineering and construction industries in the United States, the generalization of our findings to other industries and cultural contexts should be made with caution. We encourage future researchers to examine our theoretical model across industries and employees of different cultural backgrounds. The cross-sectional design of this study represents another limitation. Our results suggest that our research model’s variables are related. However, albeit the order of our variables was guided by theory, we cannot make causal inferences from our data. Future research can explore these relationships in a longitudinal design (Spector 2019), for example, how participants’ organizational citizenship behavior changes with subsequent years of growth in employee share ownership. In addition, to further explore our non-significant moderation effect, examining this relationship on a narrower referent group (e.g., direct peer or workgroup) may be more desirable. Last but not least, the nature of our data may expose our findings to single-source bias. Other researchers can examine this relationship by collecting data not only from the employees but also from their peers and supervisors (Avolio et al. 1991) or by using qualitative methods, such as case studies to gain knowledge about the social contexts that underlie human decisions and behaviors (e.g., Riar et al. 2022).

There are ample opportunities to examine the role of individual characteristics (e.g., gender, skillsets, etc.) in the relationship between different ownership modes, governance, and organizational citizenship behavior. Although organizational citizenship behavior is a well-established indicator of extra-role behaviors, alternative measures, such as stewardship (Davis et al. 1997), servant leadership (e.g., Greenleaf 1977), and organizational commitment (e.g., Allen and Meyer 1990), may be applied to examine whether they will yield different results. Similarly, it is crucial to better understand the negative consequences of psychological ownership (e.g., escalation of commitment, etc.) on employees' positive behaviors (e.g., Pierce et al. 2009) and how perceived ownership feelings are interpreted by external stakeholders when they notice them, for which a signaling theory might be useful perspective (Spence 1973; Tao-Schuchardt et al. 2023).

Last, although some basic ideas of workplace research indirectly resonate in our study (as we consider governance systems that shape employees’ work environment and ultimately their behavior), we encourage researchers to expand on our theoretical arguments based on more recent workplace-focused theories, such as the previously mentioned sociomaterial lens (e.g., Orlikowski 2007). For example, it would be interesting to analyze in more detail how the sociomateriality of the interior architecture could change old agency relationships in organizations and how shifting sociomaterial assemblages entailed in contemporary organizations influence employees feeling, attitudes, and behaviors as well as organizational processes (e.g., Bouncken and Aslam 2021). Very little is known about how the workplace design as well as the technology structure employed in the organizations can facilitate both pro-organizational behavior (as in the focus of our study) or more general team or organizational performance. Particularly when focusing on employee-owned companies, such design choices may have different consequences than for non-employee-owned firms. Accordingly, we encourage more research in this area.

References

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Alchian AA, Demsetz H (1972) Production, information costs, and economic organization. Am Econ Rev 62(5):777–795

Allen NJ, Meyer JP (1990) The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol 63:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

Aluchna M, Kuszewski T (2022) Responses to corporate governance code: evidence from a longitudinal study. RMS 16:1945–1978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00496-3

Ang JS, Cole RA, Lin JW (2000) Agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ 55(1):81–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00201

Aslam MM, Bouncken RB, Görmar L (2021) The role of sociomaterial assemblage on entrepreneurship in coworking-spaces. Int J Entrep Behav Res 27(8):2028–2049. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-07-2021-0564

Aubé C, Rousseau V, Mama C, Morin EM (2009) Counterproductive behaviors and psychological well-being: the moderating effect of task interdependence. J Bus Psychol 24(3):351–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9113-5

Avolio BJ, Yammarino FJ, Bass BM (1991) Identifying common methods variance with data collected from a single source: an unresolved sticky issue. J Manag 17(3):571–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700303

Bakan I, Suseno Y, Pinnington A, Money A (2004) The influence of financial participation and participation in decision-making on employee job attitudes. Int J Hum Resou Manag 15(3):587–616

Basterretxea I, Storey J (2018) Do employee-owned firms produce more positive employee behavioural outcomes? If not why not? A British-Spanish comparative analysis. Br J Ind Relat 56(2):292–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12247

Bayo-Moriones A, Larraza-Kintana M (2009) Profit-sharing plans and affective commitment: does the context matter? Hum Resour Manag 48(2):207–226

Beatty A (1995) The cash flow and informational effects of employee stock ownership plans. J Financ Econ 38(2):211–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20276

Beggan JK (1992) On the social nature of nonsocial perception: the mere ownership effect. J Pers Soc Psychol 62(2):229–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.2.229

Belk RW (1988) Possessions and the extended self. J Consum Res 15(2):139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

Bolduan F, Schedlinsky I, Sommer F (2021) The influence of compensation interdependence on risk-taking: the role of mutual monitoring. J Bus Econ 91(8):1125–1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-021-01030-3

Bosse DA, Phillips RA (2016) Agency theory and bounded self-interest. Acad Manag Rev 41(2):276–297. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0420

Bouncken RB, Aslam MM (2021) Bringing the design perspective to coworking-spaces: constitutive entanglement of actors and artifacts. Eur Manag J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.10.008

Bouncken RB, Aslam MM, Qiu Y (2021) Coworking spaces: understanding, using, and managing sociomateriality. Bus Horiz 64(1):119–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.09.010

Bratfisch C, Riar FJ, Bican PM (2023) When entrepreneurship meets finance and accounting: non-financial information exchange between venture capital investors, business angels, incubators, accelerators, and start-ups. Int J Entrep Ventur. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2022.10051908

Brown WS (2000) Ontological security, existential anxiety, and workplace privacy. J Bus Ethics 23:61–65. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006223027879

Bruni L, Pelligra V, Reggiani T, Rizzolli M (2020) The pied piper: prizes, incentives, and motivation crowding-in. J Bus Ethic 166(3):643–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04154-3

Buchko AA (1993) The effects of employee ownership on employee attitudes: an integrated causal model and path analysis. J Manag Stud 30(4):633–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1993.tb00319.x

Calder BJ, Staw BM (1975) Self-perception of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol 31(4):599–605

Chi NW, Han TS (2008) Exploring the linkages between formal ownership and psychological ownership for the organization: the mediating role of organizational justice. J Occup Organ Psychol 81(4):691–711. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X262314

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Kellermanns FW, Chang EP (2007) Are family managers agents or stewards? An exploratory study in privately held family firms. J Bus Res 60(10):1030–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.011

Conlon EJ, Parks JM (1990) Effects of monitoring and tradition on compensation arrangements: an experiment with principal-agent dyads. Acad Manag J 33(3):603–622. https://doi.org/10.5465/256583

Core JE, Guay WR (2001) Stock option plans for non-executive employees. J Financ Econ 61(2):253–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00062-9

Daily CM, Dalton DR, Cannella AA Jr (2003) Corporate governance: decades of dialogue and data. Acad Manag Rev 28(3):371–382. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.10196703

Davis JH, Schoorman FD, Donaldson L (1997) Toward a stewardship theory of management. Acad Manag Rev 22(1):20–47. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180258

Dawkins S, Tian AW, Newman A, Martin A (2017) Psychological ownership: a review and research agenda. J Organ Behav 38(2):163–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2057

De Jong BA, Bijlsma-Frankema KM, Cardinal LB (2014) Stronger than the sum of its parts? The performance implications of peer control combinations in teams. Organ Sci 25(6):1703–1721. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0926

Deci EL (1971) Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol 18(1):105–115

Deci EL (1975) Intrinsic motivation. Plenum Press, New York

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2012) Self-determination theory. In: Van Lange PA, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET (eds) Handbook of theories of social psychology. Sage Publications Ltd, Los Angeles, pp 416–436

Eddleston KA, Kellermanns FW, Kidwell RE (2018) Managing family members: how monitoring and collaboration affect extra-role behavior in family firms. Hum Resour Manag 57(5):957–977. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21825

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):57–74. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4279003

Evans MG (1985) A monte carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 36(3):305–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(85)90002-0

Feldman DC (1984) The development and enforcement of group norms. Acad Manag Rev 9(1):47–53. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1984.4277934

Flammer C, Hong B, Minor D (2019) Corporate governance and the rise of integrating corporate social responsibility criteria in executive compensation: effectiveness and implications for firm outcomes. Strateg Manag J 40(7):1097–1122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3018

Fong EA, Tosi HL Jr (2007) Effort, performance, and conscientiousness: an agency theory perspective. J Manag 33(2):161–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306298658

Fredrickson JW (1986) The strategic decision process and organizational structure. Acad Manag Rev 11(2):280–297. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1986.4283101

Freeman RB, Blasi JR, Kruse DL (2010) Shared capitalism at work: employee ownership, profit and gain sharing, and broad-based stock options. National Bureau of Economic Research University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Frey BS (1997) Not just for the money An economic theory of personal motivation. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham and Brookfield, Cheltenham, United Kingdom

Gagné M, Deci EL (2005) Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organ Behav 26(4):331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Glover J, Kim E (2021) Optimal team composition: Diversity to foster implicit team incentives. Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3762

Grant AM (2008) Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J Appl Psychol 93(1):48–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.48

Greenleaf RK (1977) Servant leadership: a journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press, New York

Guery L (2015) Why do firms adopt employee share ownership? Bundling ESO and direct involvement for developing human capital investments. Empl Relat 37(3):296–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2014-0016

Hallock DE, Salazar RJ, Venneman S (2004) Demographic and attitudinal correlates of employee satisfaction with an ESOP. Br J Manag 15(4):321–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2004.00422.x

Hansmann H (1996) The ownership of enterprise. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Hartman LP (1998) Ethics: the rights and wrongs of workplace snooping. J Bus Strateg 19(3):16–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039931

Hayes AF (2022) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach, 3rd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Hernandez M (2012) Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship. Acad Manag Rev 37(2):172–193. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0363

Holman D, Chissick C, Totterdell P (2002) The effects of performance monitoring on emotional labor and well-being in call centers. Motiv Emot 26(1):57–81. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015194108376

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Johns G (2006) The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad Manag Rev 31(2):386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

Keum DD (2021) Innovation, short-termism, and the cost of strong corporate governance. Strateg Manag J 42(1):3–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3216

Kim EH, Ouimet P (2014) Broad-based employee stock ownership: motives and outcomes. J Financ 69(3):1273–1319. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12150

Kreutzer M, Cardinal LB, Walter J, Lechner C (2016) Formal and informal control as complement or substitute? The role of the task environment. Strateg Sci 1(4):235–255. https://doi.org/10.1287/stsc.2016.0019

Kuvaas B, Buch R, Weibel A, Dysvik A, Nerstad CG (2017) Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation relate differently to employee outcomes? J Econ Psychol 61:244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.05.004

Larkin I, Pierce L, Gino F (2012) The psychological costs of pay-for-performance: implications for the strategic compensation of employees. Strateg Manag J 33(10):1194–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1974

Lee K, Allen NJ (2002) Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. J Appl Psychol 87(1):131–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131

Leonardi PM (2012) Materiality, sociomateriality, and socio-technical systems: what do these terms mean? How are they different? Do we need them? Materiality and organizing: social interaction in a technological world. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 25–48

LePine JA, Erez A, Johnson DE (2002) The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 87(1):52–65

Li M, Zheng X, Zhuang G (2017) Information technology-enabled interactions, mutual monitoring, and supplier-buyer cooperation: a network perspective. J Bus Res 78:268–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.12.022

Liao EY, Chun H (2016) Supervisor monitoring and subordinate innovation. J Organ Behav 37(2):168–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2035

Lindenberg S, Foss NJ (2011) Managing joint production motivation: the role of goal framing and governance mechanisms. Acad Manag Rev 36(3):500–525. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0021

Liu XY, Wang J (2013) Abusive supervision and organizational citizenship behaviour: is supervisor–subordinate guanxi a mediator? Int J Hum Resour Manag 24(7):1471–1489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.725082

Liu J, Wang H, Hui C, Lee C (2012) Psychological ownership: how having control matters. J Manag Stud 49(5):869–895

Liu F, Chow IHS, Zhang JC, Huang M (2019) Organizational innovation climate and individual innovative behavior: exploring the moderating effects of psychological ownership and psychological empowerment. RMS 13(4):771–789

Long RJ (1978) The relative effects of share ownership vs. control on job attitudes in an employee-owned company. Hum Relat 31(9):753–763

Long RJ (1980) Job attitudes and organizational performance under employee ownership. Acad Manag J 23(4):726–737

Loughry ML, Tosi HL (2008) Performance implications of peer monitoring. Organ Sci 19(6):876–890

Madison K, Kellermanns FW, Munyon TP (2017) Coexisting agency and stewardship governance in family firms: an empirical investigation of individual-level and firm-level effects. Fam Bus Rev 30(4):347–368

Mani S, Mishra M (2020) Non-monetary levers to enhance employee engagement in organizations–“GREAT” model of motivation during the Covid-19 crisis. Strateg HR Rev 30(4):171–175

Maynard MT, Gilson LL, Mathieu JE (2012) Empowerment—fad or fab? A multilevel review of the past two decades of research. J Manag 38(4):1231–1281

McCarthy D, Reeves E, Turner T (2010) Can employee share-ownership improve employee attitudes and behaviour? Empl Relat 32(4):382–395

McConville D, Arnold J, Smith A (2016) Employee share ownership, psychological ownership, and work attitudes and behaviours: a phenomenological analysis. J Occup Organ Psychol 89(3):634–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12146

Motowidlo SJ, Van Scotter JR (1994) Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. J Appl Psychol 79(4):475–480

Nyberg AJ, Fulmer IS, Gerhart B, Carpenter MA (2010) Agency theory revisited: CEO return and shareholder interest alignment. Acad Manag J 53(5):1029–1049. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.54533188

O’Boyle EH, Patel PC, Gonzalez-Mule E (2016) Employee ownership and firm performance: a meta-analysis. Hum Resour Manag J 26(4):425–448

O’Driscoll MP, Pierce JL, Coghlan AM (2006) The psychology of ownership: work environment structure, organizational commitment, and citizenship behaviors. Group Organ Manag 31(3):388–416

O’Reilly CA III, Caldwell DF (1985) The impact of normative social influence and cohesiveness on task perceptions and attitudes: a social information processing approach. J Occup Psychol 58(3):193–206

Ohly S, Sonnentag S, Pluntke F (2006) Routinization, work characteristics and their relationships with creative and proactive behaviors. J Organ Behav 27(3):257–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.376

Organ DW, Ryan K (1995) A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Pers Psychol 48(4):775–802

Orlikowski WJ (2007) Sociomaterial practices: exploring technology at work. Organ Stud 28(9):1435–1448

Osterloh M, Frey BS (2000) Motivation, knowledge transfer and organizational forms. Organ Sci 11(5):538–550. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.5.538.15204

Palanski ME, Kahai SS, Yammarino FJ (2011) Team virtues and performance: an examination of transparency, behavioral integrity, and trust. J Bus Ethic 99(2):201–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0650-7

Perryman AA, Combs JG (2012) Who should own it? An agency-based explanation for multi-outlet ownership and co-location in plural form franchising. Strateg Manag J 33(4):368–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1947

Pesch R, Endres H, Bouncken RB (2021) Digital product innovation management: balancing stability and fluidity through formalization. J Prod Innov Manag 38:726–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12609

Pierce JL, Furo CA (1990) Employee ownership: implications for management. Organ Dyn 18(3):32–43

Pierce JL, Rodgers L (2004) The psychology of ownership and worker-owner productivity. Group Organ Manag 29(5):588–613

Pierce JL, Rubenfeld SA, Morgan S (1991) Employee ownership: a conceptual model of process and effects. Acad Manag Rev 16(1):121–144

Pierce JL, Kostova T, Dirks KT (2001) Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 26(2):298–310

Pierce JL, Jussila I, Cummings A (2009) Psychological ownership within the job design context: revision of the job characteristics model. J Organ Behav 30(4):477–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.550

Podsakoff PM, Ahearne M, MacKenzie SB (1997) Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. J Appl Psychol 82(2):262–270

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Porter LW, Lawler EE (1968) Managerial attitudes and performance. Irwin, Homewood, IL

Poutsma E, Kalmi P, Pendleton AD (2006) The relationship between financial participation and other forms of employee participation: new survey evidence from Europe. Econ Ind Democr 27(4):637–667

Riar FJ, Wiedeler C, Kammerlander N, Kellermanns FW (2022) Venturing motives and venturing types in entrepreneurial families: a corporate entrepreneurship perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 46(1):44–81

Sengupta S, Whitfield K, McNabb B (2007) Employee share ownership and performance: golden path or golden handcuffs? Int J Hum Resour Manag 18(8):1507–1538

Sewell G (1998) The discipline of teams: the control of team-based industrial work through electronic and peer surveillance. Adm Sci Q 43(2):397–428

Shi W, Connelly BL, Hoskisson RE (2016) External corporate governance and financial fraud: cognitive evaluation theory insights on agency theory prescriptions. Strateg Manag J 38(6):1268–1286. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2560

Sieger P, Zellweger T, Aquino K (2013) Turning agents into psychological principals: aligning interests of non-owners through psychological ownership. J Manag Stud 50(3):361–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12017

Spector PE (2019) Do not cross me: optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J Bus Psychol 34(2):125–137

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. Q J Econ 87(3):355–374

Spitzmüller C, Stanton JM (2006) Examining employee compliance with organizational surveillance and monitoring. J Occup Organ Psychol 79(2):245–272

Stajkovic AD, Luthans F (2003) Behavioral management and task performance in organizations: conceptual background, meta-analysis, and test of alternative models. Pers Psychol 56(1):155–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00147.x

Stanton JM (2000) Reactions to employee performance monitoring: framework, review, and research directions. Hum Perform 13(1):85–113

Sue-Chan C, Hempel PS (2016) The creativity-performance relationship: how rewarding creativity moderates the expression of creativity. Hum Resour Manag 55(4):637–653. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21682

Tao-Schuchardt M, Riar FJ, Kammerlander N (2023) Family firm value in the acquisition context: a signaling theory perspective. Entrep Theory Pract. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587221135761(forthcoming)

Tosi HL, Katz JP, Gomez-Mejia LR (1997) Disaggregating the agency contract: the effects of monitoring, incentive alignment, and term in office on agent decision making. Acad Manag J 40(3):584–602

Van Dyne L, Pierce JL (2004) Psychological ownership and feelings of possession: three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. J Organ Behav 25(4):439–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.249

Vandewalle D, Van Dyne L, Kostova T (1995) Psychological ownership: an empirical examination of its consequences. Group Organ Manag 20(2):210–226

Wagner SH, Parker CP, Christiansen ND (2003) Employees that think and act like owners: effects of ownership beliefs and behaviors on organizational effectiveness. Pers Psychol 56(4):847–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00242.x

Walter J, Kreutzer M, Kreutzer K (2021) Setting the tone for the team: a multi-level analysis of managerial control, peer control, and their consequences for job satisfaction and team performance. J Manag Stud 58(3):849–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12622

Welbourne TM, Balkin DB, Gomez-Mejia LR (1995) Gainsharing and mutual monitoring: a combined agency-organizational justice interpretation. Acad Manag J 38(3):881–899

Whitfield K, Pendleton A, Sengupta S, Huxley K (2017) Employee share ownership and organizational performance: A tentative opening of the black box. Pers Rev 46(7):1280–1296

Zhang Y, Liu G, Zhang L, Xu S, Cheung MWL (2021) Psychological ownership: a meta-analysis and comparison of multiple forms of attachment in the workplace. J Manag 47(3):745–770

Zhou J (2003) When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. J Appl Psychol 88(3):413–422

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Variables, Items

Variable | Item text | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|

Organizational Citizenship behavior | I attend functions that are not required but that help the organizational image | 0.891 |

I keep up with development in the organization | ||

I defend the organization when other employees criticize it | ||

I show pride when representing the organization in public | ||

I offer ideas to improve the functioning of the organization | ||

I express loyalty toward the organization | ||

I take action to protect the organization from potential problems | ||

I demonstrate concern about the image of the organization | ||

Psychological ownership | This is MY organization | 0.938 |

I sense that this organization is OUR company | ||

I feel a very high degree of personal ownership for this organization | ||

I sense that this is MY company | ||

This is OUR company | ||

Most of the people that work for this organization feel as though they own the company | ||

It is not hard for me to think about this organization as MINE | ||

Employee Share Ownership | Approximate value of your ESOP account: $ (U.S. Dollars) | |

Agency monitoring | Personal direct observation by my supervisor? | 0.813 |

Regular assessment of short-term output by my supervisor? | ||

Progress toward long-term goals by my supervisor? | ||

Input from other managers? | ||

Thorough input from subordinates? | ||

Peer monitoring | I am aware of the overall performance of other employees in my department | 0.851 |

It is easy to notice the employees in my department whose performance is outstanding | ||

I always know when a fellow worker is doing a below-average job | ||

I notice when someone in my department does an extremely good job | ||

Within my department, it is obvious when someone does a below-average job | ||

When I notice a fellow employee doing an outstanding job, I congratulate that person | ||

When someone is working at an acceptable level, I let everyone in the department know it | ||

When someone does good work, I let everyone in the department know it | ||

If I notice an employee doing a poor job, I let that person know right away |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilhelm, B., Simarasl, N., Riar, F.J. et al. Organizational citizenship behavior: understanding interaction effects of psychological ownership and agency systems. Rev Manag Sci 18, 1–27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00610-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00610-z

Keywords

- Psychological ownership

- Organizational citizenship behavior

- Agency monitoring

- Peer monitoring

- Employee share ownership

- Agency theory