Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disease with significant implications for individual physical and mental wellbeing. Though in theory, OSA can be effectively treated with positive airway pressure therapy (PAP), many patients cannot adhere chronically and require alternative treatment. With sleep physicians being relevant stakeholders in the process of allocation of OSA treatments, this research aims to study their knowledge and perceptions of alternative therapies available in routine care in Germany.

Methods

This work is part of a larger research project which aims to assess the state of sleep medical care in Germany. Items relevant to this study included self-reported knowledge, indication volumes, and perceptions of five alternative treatments for OSA, which are available for routine care in Germany.

Results

A total of 435 sleep physicians from multiple medical disciplines and both care sectors participated in the study. Self-reported knowledge on alternative OSA treatments was moderate and correlated with the consultation volume. Self-reported adoption of alternative therapies was higher in nonsurgical methods, and only 1.1% of participants reported not utilizing any of the alternative treatments. The most relevant perceived barriers to indication were “reimbursement issues” for mandibular advancement devices and positional therapy; “evidence insufficient” for upper airway surgery, and “no demand from patients” for hypoglossal nerve stimulation and maxillomandibular Advancement.

Conclusion

Self-reported knowledge of alternative OSA treatments is moderate and indication of alternative OSA therapies varies substantially. Sleep physicians often perceive barriers that limit provision or referrals for provision of these treatments. Additional research is required to further understand barriers and factors influencing creation of those perceptions and decision-making among physicians.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Obstruktive Schlafapnoe (OSA) ist eine häufige Erkrankung mit erheblichen Auswirkungen auf das individuelle körperliche und geistige Wohlbefinden. Obwohl OSA theoretisch wirksam mit einer positiven Atemwegsdrucktherapie (PAP) behandelt werden kann, können viele Patienten diese nicht chronisch fortführen und benötigen eine alternative Behandlung. Da der Schlafmediziner ein relevanter Interessenvertreter im Prozess der Zuweisung von OSA-Behandlungen ist, zielt diese Forschung darauf ab, sein Wissen und seine Wahrnehmung der alternativen Therapien zu untersuchen, die in der Routineversorgung in Deutschland verfügbar sind.

Methoden

Diese Arbeit ist Teil eines größeren Forschungsprojekts, das darauf abzielt, den Stand der schlafmedizinischen Versorgung in Deutschland zu erfassen. Zu den für diese Studie relevanten Elementen gehörten selbstberichtetes Wissen, Indikationsmengen und Wahrnehmungen zu 5 alternativen Behandlungsmethoden für OSA, die in Deutschland für die Routineversorgung zur Verfügung stehen.

Ergebnisse

An der Studie nahmen 435 Schlafmediziner aus mehreren medizinischen Disziplinen und beiden Versorgungsbereichen teil. Das selbstberichtete Wissen über alternative OSA-Behandlungen war moderat und korrelierte mit dem Konsultationsvolumen. Die selbst gemeldete Akzeptanz alternativer Therapien war bei nichtchirurgischen Methoden höher, und nur 1,1 % der Teilnehmer gaben an, keine der alternativen Behandlungen in Anspruch zu nehmen. Die wichtigsten wahrgenommenen Hindernisse für die Indikation waren „Kostenerstattungsprobleme“ für Unterkieferprotrusionsschienen und Positionstherapie; „unzureichende Evidenz“ für die Chirurgie der oberen Atemwege und „keine Nachfrage seitens der Patienten“ für die Stimulation des N. hypoglossus und die Oberkiefer-Unterkiefer-Protrusion.

Schlussfolgerung

Die selbst angegebenen Kenntnisse über alternative OSA-Behandlungen sind mäßig, und die Indikationsstellung für alternative OSA-Therapien variiert erheblich. Schlafmediziner sehen häufig Hindernisse, die die Bereitstellung oder Überweisung dieser Behandlungen einschränken. Weitere Untersuchungen sind erforderlich, um die Hindernisse und Faktoren, die die Entstehung dieser Wahrnehmungen und Entscheidungsfindung bei Ärzten beeinflussen, besser zu verstehen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Among sleep-related breathing disorders, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is one of the most common diseases [1,2,3,4]. OSA is characterized by interruption of airflow caused by collapse of upper airway soft tissue. Due to this cessation of airflow, repeated hypoxemia and hypercapnia occur, which causes chronic systematic inflammation and repetitive sympathetic activation and can lead to development of secondary diseases of cardiovascular, metabolic, or neurologic nature, among others [5, 6]. Though affected individuals often remain asymptomatic early in the disease course, patients later present regularly with a variety of clinical symptoms ranging from nonrestorative sleep to daytime sleepiness and fatigue, depression, reduced drive, and impaired social life [7].

The diagnosis of OSA is usually established using overnight sleep recording in the form of home sleep apnea testing (HSAT) or polysomnography (PSG), from which a variety of measures can be calculated that allow estimation of disease severity. In addition, a variety of patient-reported outcome measures are in use for evaluation of general OSA-related quality of life and specific symptom domains.

Treatment of OSA is required to reduce complications and comorbidities as well as to improve symptoms. Present therapies for OSA are largely dominated by nocturnal ventilation with positive airway pressure (PAP), which was introduced in the early 1980ies and is widely available in most geographic locations [8]. Beside PAP therapy as the gold standard in treatment of OSA, a variety of non-PAP alternatives have been developed and are used to varying degrees. These are increasingly required, since 30 to 50% of patients in whom PAP treatment is initiated discontinue use and may eventually require an alternative treatment [9, 10].

Equally efficacious in selected patients suitable for this kind of treatment and with mild to moderate OSA are mandibular advancement devices (MAD) that increase the retropalatal space to avoid airway obstructions [11]. For patients with positional OSA, devices can be applied that help to avoid a supine sleeping position [12]. Contemporary position therapy devices, which are worn on the chest using a belt, apply sensing technology to detect body position and vibrate when supine posture is recognized to induce a change in body position [13]. In the surgical domain, a large variety of resecting concepts have been developed to address soft tissue collapse, with the most often applied being tonsillectomy in conjunction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) or multilevel interventions that combine various upper airway procedures [14]. An alternative surgical concept is maxillomandibular advancement to increase the posterior airway space [15]. Over the past decade, hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HNS) has been introduced as a dynamic surgical concept to treat OSA. HNS uses electrical stimulation to activate the main upper airway dilator muscles during sleep to maintain airway patency and thus avoid obstructions [16].

Whilst all these methods have been used for many years and are recommended in the current German guideline, the routine OSA treatment landscape is largely dominated by PAP therapy, though limitations are well documented and include therapy rejection due to low perceived social acceptability and insufficient adherence and discontinuation due to side effects and discomfort [17,18,19,20]. With sleep physicians being central stakeholders for treatment allocation, there is an obvious need to increase the understanding of the decision-making process for alternative non-PAP OSA treatments. Thus, we designed this study to generate insights into the knowledge of alternative treatment concepts among physicians and to further understand barriers in the allocation of those treatments from the sleep physician’s perspective.

Methods

The study was part of a larger research project conducted in 2021 that aimed to assess the status of sleep medical practice and care in Germany using a country-wide survey. In this study, more than 5000 physicians from the outpatient and inpatient sector in Germany were invited to participate in an online survey. The self-administered survey consisted of 32 questions in four categories and addressed various topics relevant to the provision of sleep medical care in Germany. The research methodology and a detailed analysis of the participants have been published previously [21].

Domains relevant for this analysis addressed the following aspects of alternative OSA treatments which were available in Germany routinely at the time when the study was conducted:

-

1.

self-reported knowledge;

-

2.

self-reported annual indications;

-

3.

perceived barriers of care which limit indication of the respective treatments.

Answers were collected using standardized categories for the different items and therapeutic concepts.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of survey data were performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics 29.0.1, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and included descriptive and concluding statistics. P-values of < 0.050 were considered statistically significant. Depending on data distribution and scales, a variety of statistical tests was applied, including Pearson’s chi-squared test, Student’s t‑test, Levene test, and linear regression analysis.

Results

Participants

The sample consisted of 435 participating physicians from multiple medical disciplines providing sleep-related care in the outpatient and inpatient sector. The details of the sample have been described previously and can be considered representative for the care structure of sleep medicine in Germany, which is dominated by providers from internal medicine, mainly with pneumology specialization, and otorhinolaryngology (Table 1 and [21]).

Self-reported knowledge of alternative OSA treatments

Knowledge of alternative treatments for OSA among German sleep physicians was assessed for the following five treatments: 1) mandibular advancement device (MAD), 2) upper airway surgery (UA surgery, such as tonsillectomy or UPPP), 3) hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HNS), 4) maxillomandibular advancement surgery (MMA), and 5) positional therapy. All therapies were routinely used in Germany when the study was conducted, though not all may have been equally accessible due to, e.g., regional differences in the medical services available.

In general, self-reported knowledge of the therapies was moderate among sleep physicians (Fig. 1), and most participants stated basic knowledge of the five alternative treatments. Only a few reported not knowing certain treatments (MAD = 0.5%; UA surgery = 1.6%; HNS = 3.5%; MMA = 6.9%; positional therapy = 0.5%). Highest knowledge scores were found for MAD treatment and positional therapy, while lowest knowledge was reported for MMA surgery. Except for UA surgery, where self-reported knowledge was lower in the inpatient sector (p = 0.030), no significant differences were found between the two care sectors. Self-reported knowledge correlated negatively with the number of sleep-related trainings [r (374) = −0.161, p = 0.002] and participant age [r (342) = −0.114, p = 0.037]. A positive correlation was found for the number of OSA consultations per year [r (422) = 0.314, p = < 0.001]. No correlation was present for length of sleep-medical practice [r (374) = 0.086, p = 0.098].

Indication of alternative OSA treatments

Overall, alternative OSA therapies were reported to be well adopted by sleep physicians in Germany (Fig. 2). Only a small number of participants reported not indicating or referring for any alternative treatments (1.1%). However, among physicians participating in this survey, indication of different alternative treatments varied widely. For example, nonsurgical alternative treatments were reported to be indicated more often than surgical interventions, with indication volumes of 25 or more indications per year reported by 32.5% (MAD) and 47.0% (positional therapy). Among surgical treatments, upper airway surgery was more often indicated than HNS therapy or MMA surgery (> 25 indications: 13.7% vs. 1.6% and 0.6%). For the latter two treatments, most participants reported not indicating or referring any patients (48.3% and 64.4%).

Significant differences in indication of alternative OSA treatments were found between care sectors. Physicians from the inpatient sector stated significantly higher indication of UA surgery versus those from the outpatient sector [t(356) = 2.373, p = 0.015] as well as for indication of HNS therapy [t(357) = 2.484, p = 0.169]. For the other three treatments, no statistically significant differences in indications were observed between the sectors (Fig. 2).

Provision of alternative treatments also varied across the responses (Fig. 3). To receive alternative treatments, patients are commonly referred to other clinicians, which is the most common provision mode. This is more pronounced for more specialized treatments like HNS therapy or maxillomandibular advancement, which are provided by a few clinics only. The exception is positional therapy, which 83% of survey participants provide in their own clinic or practice.

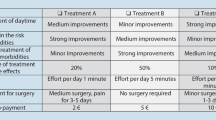

Barriers to indicating alternative OSA treatments

To assess potential barriers to the provision of alternative treatments, participants were asked about their perception of five aspects that could impact indications for each therapeutic concept. The aspects presented were 1) no contact for referral, 2) no demand from patients, 3) insufficient evidence, 4) indication unclear, and 5) issues with reimbursement. Barriers that limit indicating or referring for alternative treatments were reported for all alternative OSA therapies surveyed (Table 2). Most barriers were mentioned with MAD treatment (80.7%), HNS (69.2%), and MMA treatment (62.5%). Barriers in the utilization of positional therapy on the other hand were only reported by 43.9% of participants. The distribution of the barriers varied highly across the different treatments (Fig. 4): reimbursement issues were most often mentioned over all treatment categories and those most affected were MAD treatment (57.6% of responses), HNS (19.6% of responses), and positional therapy (18.1% of responses). Physicians in the inpatient sector reported significantly more often reimbursement limitations in general compared to those from the outpatient sector (p < 0.001). No demand from patients was reported mainly for MMA and HNS, while insufficient evidence was most mentioned with UA surgery.

Perception of the different barriers varied between physicians working in the inpatient sectors compared to those from the outpatient sector, though not all differences were statistically significant (Table 2). In general, male participants, pneumologists, and cardiologists reported significantly more often barriers to provision of alternative OSA treatments (p = 0.005, p = 0.012, and p = 0.007).

Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to test whether age, number of sleep medical trainings, reported cooperation behavior, and self-reported knowledge predict responses on barriers to alternative OSA treatments. The overall regression was statistically significant [R2 = 0.255, F(4, 236) = 4.118, p = 0.003], and it was found that self-reported knowledge of alternative therapies predicted response behavior in items on barriers that limit indication of treatments (β = −0.170, p = 0.015). Additional analysis did not reveal any statistically significant correlations for participant age (p = 0.084), number of annual OSA consultations (p = 0.921), and length of sleep medical practice (p = 0.344). A low positive correlation was found for reporting barriers with the number of sleep medical trainings [r (435) = 0.096, p = 0.045], and a low negative correlation for self-reported knowledge of alternative treatments [r (374) = −0.228, p = < 0.001].

Discussion

With an increasing prevalence of OSA and rising numbers of patients receiving treatment, the need for alternative therapies is also growing, with more patients terminating PAP therapy. Though highly efficacious and cost effective, PAP therapy as the first-line treatment is often not tolerated in chronic use, which leaves many patients with a need for alternatives to control their OSA [17, 18, 22]. This is at least partially accelerated by the lack of structured and adequately funded follow-up pathways for patients using PAP therapy, which contributes to the high rate of PAP termination. In addition, as reported recently by Woehrle et al., large numbers of patients diagnosed OSA do not receive PAP therapy [23]. Though the reasons were not identified in this study, it highlights the need for alternative treatments. Since PAP therapy would have been theoretically available for all patients, they potentially opted against it and could benefit from another form of treatment.

As experts in the field and important influencers of patient decision-making, sleep physicians play a relevant role in the allocation of alternative OSA treatments, and their knowledge and perceptions are crucial for patient access. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate knowledge of, perceived barriers to, and indication of alternative treatments for OSA from the perspective of sleep physicians in Germany. Our study shows a moderate average degree of self-reported knowledge among German sleep physicians from both the inpatient and the outpatient sector. Except for positional therapy, only a few physicians reported expert-level knowledge of alternative OSA treatments. In light of other findings from this study reported earlier, where a majority of participants reported good knowledge of recent clinical guidelines, there might be a different appraisal of high-level knowledge of guidelines and knowledge of individual treatment modalities.

While in general, knowledge of more common alternatives like MAD and positional therapy is higher, understanding of specialized surgical interventions such as HNS, MMA, and UA surgery is lower, which translates into lower self-reported indications for these treatments. On the other hand, participants reported relatively high numbers of indications for alternative OSA treatments, which can be interpreted as these being well accepted among physicians. This is supported by the fact that only a small minority of 1.1% reported not indicating any treatments beside PAP therapy.

Our study underscores one important feature of sleep medicine in Germany, which is the need for multidisciplinary provision of care. This relies on local or regional networks of different medical specialists that collaborate in the provision of services. As such, most alternative treatments are provided after referral to other physicians of a different discipline. The only exception is positional therapy, which is mostly offered within the own clinic or practice. The results presented here are supported by earlier reports from this project that show a high degree of cooperation in sleep medicine, especially among the two disciplines that dominate the provider landscape, namely otorhinolaryngology and respiratory medicine [21]. Since this multidisciplinary cooperation requires significant interaction and communication between providers, ongoing reimbursement challenges in sleep medical services—present in both the outpatient and the inpatient sector—could create disincentives for collaboration and threaten patient access. A potential solution to further increase collaboration and interdisciplinary exchange could be the implementation of local OSA boards, comparable to the “heart team” approach in cardiac care, in which members of the team discuss patient cases and optimal treatment allocation on a regular basis.

Although theoretically, all treatments except MAD, for which coverage was only introduced in 2021, are part of the benefit scheme of statutory insurance, reimbursement by third-party payors is perceived as the most relevant barrier to indication across all alternative treatments assessed. Interestingly, physicians from the inpatient sector perceive reimbursement limitations significantly more often for the treatment options UA surgery and HNS, which are mainly provided in hospitals. A common practice in Germany is ex-post denial of hospital claims by the statutory insurance’s medical service, which is reported to occur frequently and which could influence the perception of sleep physicians for these treatments [24]. This is especially important as HNS therapy was funded under special agreements and only introduced into the regular DRG catalogue in 2021.

Given the invasive nature of surgical treatments, it is not surprising that no demand from patients is reported as a barrier to these alternatives, since surgical treatment in general is often not preferred by patients in comparison to nonsurgical options [25, 26]. Although UA surgery, HNS, and MMA are recommended in OSA practice guidelines published by the German Sleep Society, which require a rigorous assessment of clinical evidence, and randomized clinical trials have been published for these interventions, a fairly large number of participants report insufficient evidence as a barrier to utilizing these treatments [20, 27]. Factors that lead to this perception could not be established from this study but should be a further part of future studies given the importance of this aspect in the provision of alternative treatments and the central role of the physician in the decision-making process.

Limitations

With a large sample size representative of the German care structure in sleep medicine, we believe that this study provides strong evidence to support the findings presented. Nevertheless, the study is subject to some limitations, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Though we were able to recruit a large sample, the overall response rate was only 9%, which appears to be low in comparison to other studies [28]. This response rate is related to the fact that a large database was used to distribute the survey to ensure that all potential physicians were reached. Also, the questionnaire was quite comprehensive and required substantial time to complete, which could have deterred some physicians. However, the geographical distribution of participants and the proportion of participants with regards to the medical disciplines corresponded to a recent analysis of sleep medical care in Germany, as discussed in the initial analysis of the survey [21]. Furthermore, the study was based on a simple survey design that relied on self-reported answers, which creates several issues. Beside overconfidence in reporting knowledge, there is a risk of socially desirable answering behavior which might influence the responses. However, with a relatively large and balanced sample, we believe that the risk of bias is limited. It is also important to have in mind that the survey did not test the knowledge, which might have led to more precise estimation of knowledge. The time burden associated with a more sophisticated survey design was considered too high, and it was decided to use this approach to lower the risk of dropouts. Another limitation arises from the fact that knowledge and perceptions are fluid and subject to constant external influences. Ongoing continuous medical education, changing medical practice guidelines, and reimbursement decisions will impact upon how available treatments are perceived and indicated in routine care. Recently, MAD treatment was added to the benefit catalogue of the statutory health insurance, which will reduce reimbursement limitations present before this decision [29]. Finally, knowledge and perceived barriers are only parts of the actual decision-making process, and other factors, e.g., immediate availability in the local healthcare ecosystem, personal preferences, and administrative aspects, will influence adoption and utilization of treatments. To further assess the factors driving these circumstances, additional research is warranted.

Conclusion

Self-reported knowledge of alternative OSA treatments is moderate among sleep physicians in Germany, and only a minority report expert knowledge. Utilization of these therapies is common but varies significantly, and is often carried out within networks of different medical specialties. Sleep physicians frequently perceive barriers to the provision of those treatments across all alternative treatments, which highlights the need for optimization of care pathways and continuous education of providers. For MAD and positional therapy, reimbursement issues were perceived as most relevant barrier, while insufficient evidence was reported most often for UA surgery, and no demand from patients was perceived as the main barrier to indication of HNS and MMA treatments.

Data availability

Data from this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Benjafield AV et al (2019) Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med 7(8):687–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5

Arnardottir ES, Bjornsdottir E, Olafsdottir KA, Benediktsdottir B, Gislason T (2016) Obstructive sleep apnoea in the general population: highly prevalent but minimal symptoms. Eur Respir J 47(1):194–202. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01148-2015

Fietze I et al (2018) Prevalence and association analysis of obstructive sleep apnea with gender and age differences—results of SHIP-trend. J Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12770

Heinzer R et al (2015) Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med 3(4):310–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00043-0

Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP (2010) Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev 90(1):47–112. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00043.2008

Young T et al (2008) Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep 31(8):1071–1078

Shepertycky MR, Banno K, Kryger MH (2005) Differences between men and women in the clinical presentation of patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 28(3):309–314

Sullivan CE, Berthon-Jones M, Issa FG, Eves L (1981) Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the NARES. Lancet 317(8225):862–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(81)92140-1

Kohler M, Smith D, Tippett V, Stradling JR (2010) Predictors of long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure. Thorax 65(9):829–832. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.135848

Woehrle H et al (2024) PAP telehealth models and long-term therapy termination: a healthcare database analysis. ERJ Open Res. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00424-2023

Ng JH, Yow M (2020) Oral appliances in the management of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 15(2):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.02.010

Barnes H, Edwards BA, Joosten SA, Naughton MT, Hamilton GS, Dabscheck E (2017) Positional modification techniques for supine obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 36:107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.11.004

Berry RB et al Nightbalance sleep position treatment device versus auto-adjusting positive airway pressure for treatment of positional obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 15(07):947–956. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.7868

Su Y‑Y et al (2022) Systematic review and updated meta-analysis of multi-level surgery for patients with OSA. Auris Nasus Larynx 49(3):421–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2021.10.001

Giralt-Hernando M, Valls-Ontañón A, Guijarro-Martínez R, Masià-Gridilla J, Hernández-Alfaro F (2019) Impact of surgical maxillomandibular advancement upon pharyngeal airway volume and the apnoea-hypopnoea index in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res 6(1):e402. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000402

Strollo PJJ et al (2014) Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 370(2):139–149. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1308659

Fietze I et al Wenn CPAP nicht genutzt oder nicht vertragen wird – Vorschlag für eine standardisierte Terminologie. Somnologie. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-020-00233-0

Schoch OD, Baty F, Niedermann J, Rüdiger JJ, Brutsche MH (2014) Baseline predictors of adherence to positive airway pressure therapy for sleep apnea: a 10-year single-center observational cohort study. Respiration 87(2):121–128. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354186

Pépin J‑L et al (2021) CPAP therapy termination rates by OSA phenotype: a French nationwide database analysis. J Clin Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050936

Stuck BA et al (2020) Teil-Aktualisierung S3-Leitlinie Schlafbezogene Atmungsstörungen bei Erwachsenen. AWMF

Stuck BA, Schöbel C, Spiegelhalder K (2023) Die schlafmedizinische Versorgung in Deutschland. Somnologie 27(1):36–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-022-00345-9

Ritter J, Geißler K, Schneider G, Guntinas-Lichius O (2018) Einfluss einer strukturierten Nachsorge auf die Therapietreue bei OSAS-Patienten unter CPAP-Therapie. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol 97(9):615–623. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0640-9198

Woehrle H et al (2023) Prevalence and predictors of positive airway pressure therapy prescription in obstructive sleep apnoea: a population-representative study. Somnologie. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-023-00435-2

Rosery H, Wollny M, Götz V (2023) Überprüfungen von Krankenhausleistungen durch den Medizinischen Dienst. Optimierung der Entscheidungsprozesse, p 20

Braun M, Dietz-Terjung S, Taube C, Schoebel C (2022) Patient preferences in obstructive sleep apnea—a discrete choice experiment. Sleep Breath. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02549-z

Braun M, Dietz-Terjung S, Taube C, Schoebel C (2022) Treatment preferences and willingness to pay in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: relevance of treatment experience. Somnologie 26(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-021-00331-7

Mayer G et al (2017) German S3 guideline nonrestorative sleep/sleep disorders, chapter ‘sleep-related breathing disorders in adults,’ short version: German sleep society (deutsche Gesellschaft für Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin, DGSM). Somnologie 21(4):290–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-017-0136-2

Kellerman SE, Herold J (2001) Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 20(1):61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0

Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Unterkiefer-Protrusionsschiene: G‑BA regelt zahnärztliche Details für Verordnung. https://www.g-ba.de/presse/pressemitteilungen-meldungen/954/. Accessed 16 Nov 2023

Funding

This study was supported by ResMed Germany and Inspire Medical Systems. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Braun and B. Stuck conceived the original idea, planned and carried out the study, and analyzed the data. M. Braun wrote the manuscript with support from B. Stuck.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Braun received personal fees from Onera Health and serves as a consultant for AstraZeneca. B. Stuck has received research grants, reimbursement of travel expenses, and speaking fees from Neuwirth Medical Products, XM Consult, Inspire Medical, UV-smart, Itamar, Sanofi, Merck, and Nyxoah. His department has received financial support for meetings or symposia from Advanced Bionics, ALK, Atos, Bess, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cochlear, Fahl, Inspire, Löwenstein Medical, Medel, Merck, MSD, Neuwirth Medical Products, Novartis, Oticon, Otopront, Pohl-Boskamp, Sanofi, Spiggle&Theis, Storz, Takeda, Zeiss, Bioprojet, Fresenius Kabi. He serves as a consultant for Itamar Medical and UV smart.

Ethics committee approval was not required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Braun, M., Stuck, B. Physician self-reported knowledge of and barriers to indication of alternative therapies for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Somnologie (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-024-00459-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-024-00459-2