Abstract

Purpose

Patients with cancer often experience multiple somatic and psychological symptoms. Somatic and psychological symptoms are thought to be connected and may reinforce each other. Network analysis allows examination of the interconnectedness of individual symptoms. The aim of this scoping review was to examine the current state of knowledge about the associations between somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer and cancer survivors, based on network analysis.

Methods

This scoping review followed the five-stage framework of Arksey and O’Malley. The literature search was conducted in May, 2023 in PubMed, APA PsycINFO, Embase Cochrane central, and CINAHL databases.

Results

Thirty-two studies were included, with eleven using longitudinal data. Seventeen studies reported on the strength of the associations: somatic and psychological symptoms were associated, although associations among somatic as well as among psychological symptoms were stronger. Other findings were the association between somatic and psychological symptoms was stronger in patients experiencing more severe symptoms; associations between symptoms over time remained rather stable; and different symptoms were central in the networks, with fatigue being among the most central in half of the studies.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Although the associations among somatic symptoms and among psychological symptoms were stronger, somatic and psychological symptoms were associated, especially in patients experiencing more severe symptoms. Fatigue was among the most central symptoms, bridging the somatic and psychological domain. These findings as well as future research based on network analysis may help to untangle the complex interplay of somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Patients with cancer often experience multiple symptoms related to their disease and treatment [1,2,3]. A distinction is generally made between somatic and psychological symptoms [4,5,6], which corresponds to a similar distinction between biological and psychological factors in the biopsychosocial model of health and its applications (e.g., [7,8,9]). Both cancer and its treatment may cause a wide range of somatic symptoms. Examples include nausea, lack of appetite, and pain [10, 11]. Cancer diagnosis and treatment lead to a process of psychological adjustment [12]; this may be accompanied by numerous psychological symptoms, such as depressive mood or anxiety [13, 14]. For some symptoms, it is less clear whether they are somatic or psychological because they may be linked to the disease and treatment as well as to the process of adaptation. Fatigue is a prime example [15,16,17,18]. A true distinction between somatic and psychological symptoms is not possible, as mind and body are not separate entities and their functioning involves shared processes [19]. Nevertheless, the distinction between somatic and psychological symptoms, with some symptoms having an undecided status, is well-established in research and clinical practice [10, 13,14,15].

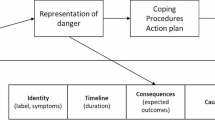

Somatic and psychological symptoms have frequently been found to be associated [15, 20,21,22]. However, the associations tend to be limited or are found only for certain components of mental health (e.g., depression but not distress) [23, 24]. These studies typically use latent constructs to assess somatic and psychological symptoms. In this approach, symptoms are viewed as interchangeable consequences of an underlying cause, such as cancer (for somatic symptoms) or a mental disorder (for psychological symptoms) [19]. The network theory offers a different approach to examine somatic and psychological symptoms and their association. The network theory [25] views symptoms as causally connected within a network. Network models consist of nodes (the variables or symptoms of interest) and edges (the lines between the nodes that depict the association between the nodes; see Fig. 1). In case of strong connections between symptoms in the network, activation of one symptom leads to the activation of other symptoms, resulting in cascading activation of symptoms [26]. Network analysis appears ideally suited to capture the complexity of the interplay between somatic and psychological symptoms [27]. Instead of looking for underlying causes of somatic and psychological symptoms and their association, network analysis captures the association among somatic and psychological symptoms at the level of the symptoms themselves [19]. As a result, regardless of whether a symptom (e.g., lack of appetite) is primarily due to the cancer and its treatment or to psychological adaptation, the interaction of the symptom with other symptoms can be examined directly [26]. While symptoms can often indeed be attributed primarily to cancer and its treatment or to the process of psychological adaptation, network analysis offers the opportunity to study the interaction between symptoms without assuming a particular cause of symptoms in advance. See [27] for more information on network analysis.

Research on the association between somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer based on network analysis is an emerging field. An overview of the major research themes and findings in this field is not yet available. The aim of this scoping review was to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge about the association between somatic and psychological symptoms in people with cancer and cancer survivors, based on network analysis.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted, using the five-stage framework from Arksey and O’Malley [28]. The five stages of review included the following: (1) identification of the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results [28]. We followed the PRISMA guidelines for reporting on scoping reviews [29]. No ethics approval was required for this review.

Identification of relevant studies

The final literature search was conducted in May 2023. The search terms focused on study population, reported symptoms, and analytic technique. For study population, both patients with cancer and cancer survivors ≥ 18 years old were included. Survivors were included because there is no sharp distinction between patients and survivors, and survivors also experience a wide range of somatic and psychological symptoms. In this review, the term “patients” can refer to patients, survivors, or both. Search terms for symptoms included both somatic and psychological symptoms that are common during or after cancer treatment, such as “nausea,” “lack of appetite,” “anxiety,” and “depression.” For analytic technique, search terms related to network analysis were included. See Appendix A for the search in PubMed.

Potential relevant articles were identified through a systematic search using a combination of operator-specific keywords in the PubMed, APA PsycINFO, Embase, Cochrane central, and CINAHL databases. References of included articles and relevant reviews were hand-searched for eligible articles.

Study selection

Full-text articles were selected if they (1) included a sample of patients with cancer or cancer survivors, aged 18 years or older; (2) reported on the association between somatic and psychological symptoms; (3) used network analysis to examine this association; (4) were published in peer-reviewed journals; and (5) were written in English. Reviews, commentaries, abstracts, and other articles that did not include data based on network analysis were excluded.

The study selection consisted of two stages. In the first stage, all articles were screened by title and abstract by one reviewer (ED). Inter-rater reliability was checked as follows. In addition to the primary reviewer ED, two independent reviewers (FL and JD) screened a random sample of 50 articles. The cut off to be met was kappa = 0.80 with the primary reviewer. The observed kappa’s were 0.88 for JD and ED and 0.88 for FL and ED. Because of the high interrater agreement, one reviewer (ED) performed the final study selection. In case of uncertainty, the selection was discussed with another reviewer (FL). In the second stage, the full texts of all articles identified as potentially relevant were read by two reviewers (ED and FL). Results were compared and discrepancies among the reviewers were discussed. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer (JD) was consulted.

Charting the data

The following information was extracted from the included studies: study population, study objective(s), symptoms assessed, symptom assessment method, analytical method and statistical packages used, centrality indices (see Box 1 for more information), results, and the conclusion. When certain information could not be directly retrieved from the article, the authors were contacted. One reviewer (ED) extracted the data. The second reviewer (FL) extracted data of 10% of the papers to check accuracy.

Box 1 Centrality indices.

Centrality indices Centrality analyses are conducted to measure which variables are most central in the network (i.e., the variables with the strongest connections in the network [21, 30]) Four common measures are as follows: • Degree centrality: represents the number of connections of a node [30] • Closeness: measures the distance between a node and all other nodes in the network [21] • Betweenness: measures how often a node lies in the shortest path between every combination of two nodes [21] • Strength: is the sum of all edge strengths to or from a node [21] Additional centrality indices exist, which provide insights into different dimensions of centrality |

Symptoms were categorized as somatic, psychological, or undecided. Somatic symptoms were defined as symptoms that are primarily caused by cancer or cancer treatment. Psychological symptoms were defined as symptoms that are primarily aspects of the psychological adjustment to the cancer diagnosis. Certain symptoms have both strong psychological and somatic aspects: these symptoms were labeled as undecided. The classification of symptoms is listed in Appendix B.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The associations between somatic and psychological symptoms were extracted. Authors were contacted to retrieve edge weights or partial correlations, if not reported. The measures and reporting of effect sizes varied among the articles. Therefore, for the interpretation of the results we used the authors’ interpretation of the strengths, as well as the absolute or relative edge strength within the network, or the network density (i.e., the number of associations in the network relative to the total number of associations possible). For edge weights and partial correlations, we most often used the relative strength for the interpretation of the associations, for Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlations, coefficients were interpreted as follows: ≤ 0.3 = weak; > 0.3 < 0.7 = moderate; ≥ 0.7 = strong [31]. Additionally, articles were searched for themes that they had in common, to summarize the findings (as will be reported, the themes were the clustering of symptoms, characteristics of symptoms, the associations of symptoms over time, and centrality).

Results

Overview of included studies

The initial search yielded 639 articles. After duplicates were removed, 356 unique articles remained. Title and abstract screening excluded 316 articles; 42 articles underwent a second stage of screening based on their full-text. Reviewers reached consensus to include 32 articles in the review. The flow diagram and reasons for exclusion are shown in Fig. 2.

All included articles were published between 2016 and 2023. Over half of the articles were published between 2021 and 2023. Twelve articles included patients during active treatment [3, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], eight articles included patients with cancer who already completed their treatment [2, 16, 18, 43,44,45,46,47], eight studies included patients during and following treatment [21, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54], while four articles did not specify treatment status [55,56,57,58]. Thirteen articles focused on one cancer type, mostly breast cancer [3, 18, 21, 41, 42, 44, 57]. The other studies investigated multiple myeloma [36], brain [48, 53], head and neck [38, 40], prostate [52], or gastric cancer [33]. Four articles included multiple pre-defined cancer types [32, 34, 35, 45], the remaining thirteen articles did not have specific inclusion criteria regarding cancer type [2, 16, 37, 39, 43, 46, 47, 49,50,51, 54,55,56, 58]. Half of the studies had more female than male participants. The mean age ranged from 34 to 68 years. See Table 1 for study characteristics.

The studies varied in sample size (range N = 1–4020), number of symptoms used in the analysis (range 2–41 symptoms), as well as in the use of single items versus sum scores. Twenty-one articles reported on cross-sectional data, ten reported on longitudinal data, and one article reported on both longitudinal and cross-sectional data. The objective of most articles was to examine the interconnectedness of symptoms in patients with cancer, with a specific focus. The focus entailed for example the development of models that can provide information on symptom networks [21, 54] or the use of individual networks in the treatment of symptoms [16, 43, 46, 47]. All study aims are shown in Table 1. Almost all analyses were conducted in R, with different packages used for the construction of the network. Most articles examined centrality indices such as strength centrality, betweenness and closeness. Other indices such as the stability and accuracy of the networks were also examined, albeit less often. The number of somatic and psychological symptoms that was assessed was most often not equal. In general, more psychological symptoms were included in the models compared to somatic or undecided symptoms.

Association between somatic and psychological symptoms

All articles reported at least one association between somatic and psychological symptoms in their network(s). The number of associations between somatic and psychological symptoms varied across studies, as well as the strength. The strength of these associations was reported in (the supplementary materials of) eight articles. The authors of 24 articles that did not report on the strength of the associations were contacted. For nine articles, additional information was provided upon request, while for the remaining fifteen articles no additional information was received. Overall, weak associations were reported between somatic and psychological symptoms. Two studies reported that all symptoms within the network were strongly correlated [52, 53]. One study specifically mentioned strong associations between somatic (physical limitations in daily life) and psychological complaints in patients with severe symptoms [49]. The inspection of the available correlation or edge weight matrices showed that cross-domain associations (i.e., between symptoms from the somatic and psychological domain) were often smaller than associations within the same domain. To illustrate, a study among breast cancer patients reported that mood swings and irritability had an edge weight of 0.70, while neither mood swings nor irritability had larger edge weights than 0.13 with any of the somatic items (such as hot flashes or headaches) [3]. Stronger associations within than across domains were observed for both studies examining patients in active treatment and after treatment.

Clustering of symptoms

Because almost half of the articles did not include (or provide) a correlation or edge weight matrix, we further looked at clusters or communities within the networks. Moreover, we looked at the visualization of the networks to compare the relative strength of the associations. Multiple studies analyzed clusters or communities of symptoms within a network [18, 21, 32, 34, 35, 38, 39, 44, 45, 48, 49, 55, 58], three of which exclusively examined patients after treatment [18, 44, 45]. A number of studies found one or more clusters that consisted of both somatic and psychological symptoms [21, 34, 35, 45, 48, 49, 57, 58]. Examples of these cross-domain clusters are a cluster of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, pain and dyspnea [34], or fatigue, pain, emotional symptoms, appetite loss, and dyspnea [45]. More symptom clusters were reported that fall within either the somatic or psychological domain, as compared to cross-domain clusters [18, 32, 34, 35, 39, 48, 55, 58]. Examples are a somatic cluster of faintness, pain on heart, nausea, trouble getting breath, numbness, weakness, and physical problems [39] and a psychological cluster of having no interest, nervousness, feeling lonely, feeling blue, tense and keyed up, scared for no reason, worthlessness, panic, hopelessness, restlessness, thoughts about ending life, fearfulness, and thoughts about death [39]. Overall, the cluster analyses and the visual inspection of networks showed that somatic as well as psychological symptoms were more strongly associated among themselves than with each other. Undecided symptoms such as fatigue were often associated with both somatic and psychological symptoms and were found in both same-domain and cross-domain clusters.

Characteristics of symptoms

In one of the included articles, Papachristou and colleagues [32] analyzed symptoms of patients receiving chemotherapy in three different ways. They examined symptom occurrence (prevalence of symptoms), symptom severity (importance of symptoms), and symptom distress (influence of symptoms). They reported that the association among symptoms differed depending on what characteristic was used to examine symptoms. Likewise, the corresponding networks showed different associations between somatic and psychological symptoms. Most of the other studies measured severity of symptoms, some measured occurrence and a few used frequency or distress.

Three studies compared the network connectivity of patients with low, moderate, or high severity of symptoms [41, 48, 49]. Neijenhuijs and colleagues [49] examined 26 symptoms in 1330 cancer survivors, of which 60% had completed their treatment; they classified symptoms that were reported by the participants as “no risk for well-being,” “moderate risk for well-being,” or “high risk for well-being.” They observed more connections between self-reported somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with high risk scores, compared to patients with medium-to-high risk scores. In patients with high risk scores, psychological complaints and physical limitations were most central and were connected to nearly all symptoms. Bergsneider and colleagues [48] examined 20 symptoms among 1128 patients receiving treatment, or following treatment for a brain tumor. They found that the subgroup of patients with the highest occurrence and severity of symptoms had a stronger overall interconnectivity among the symptoms within the network, as compared to patients with less severe symptoms. This finding held for the associations between psychological and somatic symptoms as well. Cai and colleagues [41] examined 41 symptoms among 1033 women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy and analyzed subgroups of patients with different levels of symptom severity. They did not statistically compare the density of the networks, but the network of the severe symptom subgroup showed thicker edges as compared to the moderate or mild symptom subgroups.

Symptoms over time

Out of the eleven articles that reported on longitudinal data [16, 18, 33,34,35, 39, 40, 43, 46, 47, 56], nine articles reported on changes in network connectivity over time [16, 18, 33,34,35, 40, 43, 47, 56]. Despite the differences in time span across the studies (ranging from a couple of weeks to 8 years), and regardless of treatment status (in active treatment or after treatment), the articles reported that symptom clusters remained rather stable over time. Because the authors did not provide an explicit report on whether this was also the case for the associations between somatic and psychological symptoms, the networks were visually inspected. Connections between somatic and psychological symptoms were often visible at multiple time points, while there were also associations that changed from one time point to the next.

Rha and Lee [34] found stable symptom clusters over the course of four cycles of chemotherapy. These entailed the association between anxiety and dyspnea at four out of five time points, for example. Airaksinen and colleagues [56] examined the connectedness of depressive symptoms 4 and 2 years before diagnosis, as well as 2 and 4 years after diagnosis. They found that the connectivity among symptoms had not changed significantly since the time prior to the diagnosis. Moreover, the associations of restless sleep with psychological symptoms of depression (such as sadness or feeling depressed) were present at all time points. In contrast, some studies (e.g., [18, 33]) showed some variation in associations between somatic and psychological symptoms over time. An example is the article from Kalantari and colleagues [35], who used data from the same dataset as [34]. They found a core set of symptoms within the clusters that were consistently present over two cycles of chemotherapy, while the specific associations between somatic and psychological symptoms had changed.

Central symptoms

Centrality analyses revealed a range of symptoms that were most central within a network. Fatigue was most often reported as (one of) the most central symptom(s), in 16 out of 32 studies [18, 21, 32,33,34,35, 38, 40,41,42, 45, 48, 49, 51, 53, 55, 58], of which seven studies examined patients in active treatment [32,33,34,35, 38, 40,41,42], two studies examined patients following treatment [18, 45], four examined patients during and after treatment [48, 49, 51, 53], and two did not specify treatment status [55, 58]. In contrast, one study among cancer survivors reported that fatigue was among the least central symptoms within the network [2]. No apparent differences were found in the design of this study, as compared to others. Other examples of central symptoms were depression/depressed mood [18, 40, 50, 56], sadness [2, 33, 39, 57], and loss of enjoyment [50, 52]. In longitudinal studies, central symptoms differed across time points. For example, Shim and colleagues [33] found different central symptoms before surgery (shortness of breath and fatigue), 1 week after surgery (fatigue) and 3–6 months after surgery (physical well-being).

Treatment status

The results regarding associations between somatic and psychological symptoms, the clustering of symptoms, the characteristics of symptoms and symptoms over time were compared between studies that examined patients during, after, or during and after treatment. No substantial differences were found in the results of studies that examined patients in active treatment versus patients after treatment.

Discussion

This scoping review summarized the evidence on the association between somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer and cancer survivors based on network analysis. Key findings were that (a) stronger associations were reported among psychological symptoms and among somatic symptoms than between somatic and psychological symptoms; (b) the association between somatic and psychological symptoms was stronger in patients experiencing more severe symptoms; (c) the association between somatic and psychological symptoms remained rather stable over time; and (d) different symptoms played a central role in the network, with fatigue being most frequently reported.

Associations between psychological and somatic symptoms

All studies reported associations between somatic and psychological symptoms. Earlier reviews in patients with cancer also showed connections between somatic and psychological symptoms [59,60,61]. These reviews focused on specific symptoms and did not limit their search to network analysis. The present study found stronger associations among somatic symptoms and among psychological symptoms than between somatic and psychological symptoms. Previous reviews on symptom clusters in patients with cancer have also identified separate psychological and somatic (gastrointestinal) clusters of symptoms [62, 63]. Therefore, we tentatively conclude that in patients with cancer psychological symptoms and somatic symptoms are more strongly associated among themselves than with each other. This finding may, in part, be due to method variation. Symptoms are likely to be more strongly correlated to symptoms from that same questionnaire as compared to symptoms measured with another questionnaire, because questionnaires are often developed with the intention to have a high internal consistency. Because several articles used one questionnaire for somatic symptoms and another questionnaire for psychological symptoms, it is possible that this explains at least partially the observed pattern of stronger associations among psychological symptoms and among somatic symptoms than between these symptom domains. Therefore, the results of this review should be interpreted with the study objectives and the chosen methods in mind.

Characteristics of symptoms

One study reported that the associations among somatic and psychological symptoms differed depending on which symptom characteristic was measured (occurrence, severity, or distress) [32]. This is in line with a review on symptoms clusters in patients with cancer, not using network analysis [63]. Regarding symptom severity, three studies found that the association among somatic and psychological symptoms was stronger in patients with more severe symptoms [41, 48, 49]. Because strong association among symptoms might cause more symptoms within the network to be activated in case of an adverse event, this finding is worth examining in future research.

Association over time

In this review, we found nine longitudinal studies that examined changes in associations over time. These studies reported rather stable associations among somatic and psychological symptoms over time. In contrast, an earlier review on symptom clusters (not using network analysis) found that only over a third of the studies reported relatively stable clusters over time [63], and another review reported low stability in symptom clusters among breast cancer patients over time [64]. It is possible that, in contrast to symptoms clusters in general, the association between psychological and somatic symptoms is rather stable over time. If confirmed in future studies, further research is needed to explain this finding.

Central symptoms

The majority of studies found that fatigue was one of the most central symptoms within their network. Fatigue has both somatic and psychological aspects; whether somatic aspects or psychological aspects are more prominent may depend on tumor activity and treatment status [65]. Moreover, fatigue is experienced in the majority of patients [15, 46, 54]. Because of its central position, fatigue was proposed as a possible target for interventions [18, 21, 40, 46, 48]. However, other factors than centrality can determine the influence of a symptom on the network [18]. Additionally, the centrality of symptoms is highly dependent on which symptoms are included in the network.

Treatment status

It is plausible that the nature of symptoms during and after treatment differ, where symptoms during treatment follow the cycles of treatment, and symptoms after treatment may be more persistent in nature. However, no clear differences were found regarding the association between somatic and psychological symptoms, the characteristics of symptoms, symptoms over time, and central symptoms. Possibly, the number of included studies is too small to detect such differences.

Challenges to study comparison

An overarching challenge to compare study results was the heterogeneity of the studies. Studies differed in design, sample size, symptoms assessed, measurement instruments, and number of time points. This hampered comparing and interpreting the findings. Moreover, the majority of the studies did not report on the associations between somatic and psychological symptoms in detail, as it was not the main focus of these studies. Similarly, while articles visualized networks and often reported on centrality indices, the effect sizes for specific associations could not be retrieved for fifteen articles. Future network analyses would benefit from reporting on the strength, such as (partial) correlation coefficients or edge weights. Burger and colleagues [66] developed reporting standards for network analyses on cross-sectional data.

Study limitations

This review has several limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, it was not always easy to determine whether symptoms are primarily caused by cancer and its treatment, or primarily by psychological adjustment to the disease. It is therefore important to note that the classification of symptoms is a simplification of the complex interplay between somatic and psychological symptoms. Secondly, studies written in other languages than English were not included.

Clinical implications

Despite these limitations, this review has some tentative clinical implications. Somatic and psychological symptoms are associated; possibly somatic symptoms activate psychological symptoms, and somatic symptoms activate psychological symptoms. By means of individual networks, it can be examined which somatic and psychological symptoms are particularly connected for a patient (even over time and especially in patients with severe symptoms). This can inform which somatic symptoms can be possible targets for intervention to alleviate psychological symptoms, or which psychological symptoms can be targeted to improve somatic symptoms [67]. This review showed that fatigue is a prominent symptom in half of the studies. This emphasizes the importance of this and other symptoms that can be related to cancer and its treatment, as well as to psychological adjustment. However, more longitudinal studies are necessary to untangle the complex interplay of somatic and psychological symptoms.

Future directions

This scoping review focused on network analysis to examine symptoms in patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Based on the results from the present study and findings in the field of psychopathology, we argue that future research would benefit from exploring the application of network analysis in the symptom management of patients with cancer further. This study showed the diverse application of this technique. A major benefit of network analysis is that it provides the means to look at the interplay between symptoms, instead of focusing on an underlying disease or disorder. This is especially beneficial when looking at symptoms that can have multiple causes (both disease-related as psychological), as is the case in the symptom experience in patients with cancer. More longitudinal studies are necessary to be able to understand the complex interplay of symptoms better. Longitudinal studies using for example ecological momentary assessment may be a step forward into the understanding of the association between somatic and psychological symptoms. This is because longitudinal studies can show which symptoms are influencing symptoms at later time points, or which symptoms may be easily influenced by other symptoms in the network. Symptoms that impact other symptoms in the network could become targets at interventions, or symptoms to monitor during treatment to decrease a cascading effect of symptoms [68]. Therefore, longitudinal studies add to the knowledge of cross-sectional studies that can only show which symptoms co-occur. Through the limited, yet growing number of available studies, this study highlights the promise of network analysis in the examination—and perhaps even the management—of somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer.

Conclusions

Although the associations among somatic symptoms and among psychological symptoms were stronger, somatic and psychological symptoms were associated, especially in patients experiencing more severe symptoms. The association between psychological and somatic symptoms remained rather stable over time. Fatigue was one of the most central symptoms, bridging the somatic and psychological domain. This review shed light on the emerging field of research on the association between somatic and psychological symptoms based on network analysis and summarized the major findings. Further longitudinal research using the network approach is needed to unveil the complex interplay of somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer.

References

Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K. Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004(32):17–21.

Zhu Z, et al. Contemporaneous symptom networks of multidimensional symptom experiences in cancer survivors: a network analysis. Cancer Med. 2023;12(1):663–73.

Jing F, et al. Contemporaneous symptom networks and correlates during endocrine therapy among breast cancer patients: a network analysis. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1081786.

Nipp RD, et al. The relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and health care utilization in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(23):4720–7.

Roziner I, et al. Psychological and somatic symptoms among breast cancer patients in four European countries: a cross-lagged panel model. Stress Health. 2023;39(2):474–82.

Riba MB, et al. Distress management, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(10):1229–49.

Organisation, W.H., The constitution of the World Health Organisation. 1948, WHO: Washington, DC.

Engel, G.L., The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. 1977, TScience. p. 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Tucker CA, et al. Mapping the content of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)) using the International Classification of Functioning. Health and Disability Qual Life Res. 2014;23(9):2431–8.

Fallon M, et al. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Annals Oncol. 2018;29:iv166–91.

Kang D, et al. Surveillance of symptom burden using the patient-reported outcome version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events in patients with various types of cancers during chemoradiation therapy: real-world study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9: e44105.

Dekker J, de Groot V. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease and rehabilitation - an exploration. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(1):116–20.

Cook SA, et al. Predictors of emotional distress a year or more after diagnosis of cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncol. 2018;27(3):791–801.

Cook SA, et al. The association of metacognitive beliefs with emotional distress after diagnosis of cancer. Health Psychol. 2015;34(3):207–15.

Zhu L, et al. Co-morbidity of depression, anxiety and fatigue in cancer patients receiving psychological care. Psychooncol. 2017;26(4):444–51.

Schellekens MPJ, Bootsma TI, van Woezik RAM, van der Lee ML. Personalizing psychological care for chronic cancer-related fatigue: a case study on symptom dynamics. J Pers Oriented Res. 2021;7(1):1–13.

Nikendei C, et al. Depression profile in cancer patients and patients without a chronic somatic disease. Psychooncol. 2018;27(1):83–90.

Poikonen-Saksela P, et al. A graphical LASSO analysis of global quality of life, sub scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 instrument and depression in early breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):2112.

van der Lee ML, Schellekens MPJ. Capturing the complexity of mental disorders in the medically ill: the network approach on behavioral medicine. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(3):812–6.

Petrova D, et al. Physical comorbidities as a marker for high risk of psychological distress in cancer patients. Psychooncol. 2021;30(7):1160–6.

Henry TR, et al. Concordance networks and application to clustering cancer symptomology. Plos One. 2018;13(3): e0191981.

Syrjala KL, et al. Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1703–11.

Teunissen SCCM, de Graeff A, Voest EE, de Haes JCJM. Are anxiety and depressed mood related to physical symptom burden? A study in hospitalized advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):341–6.

McFarland DC, Shaffer KM, Tiersten A, Holland J. Physical symptom burden and its association with distress, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(5):464–71.

Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13.

Robinaugh DJ, Hoekstra RHA, Toner ER, Borsboom D. The network approach to psychopathology: a review of the literature 2008–2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol Med. 2020;50(3):353–66.

Borsboom D, Cramer AO. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Fried EI, et al. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(1):1–10.

Akoglu H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018;18(3):91–3.

Papachristou N, et al. Network Analysis of the multidimensional symptom experience of oncology. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2258.

Shim EJ, et al. Network analyses of associations between cancer-related physical and psychological symptoms and quality of life in gastric cancer patients. Psychooncol. 2021;30(6):946–53.

Rha SY, Lee J. Stable symptom clusters and evolving symptom networks in relation to chemotherapy cycles. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(3):544–54.

Kalantari E, et al. Network analysis to identify symptoms clusters and temporal interconnections in oncology patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17052.

Zeng L, et al. The core symptom in multiple myeloma patients undergoing chemotherapy: a network analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(5):297.

Liu Y, et al. How dignity-related distress interacts with quality of life in young adult patients with cancer during the active treatment stage: a network analysis. Psychooncol. 2022;31(9):1564–71.

Santoso AMM, et al. Psychoneurological symptoms and biomarkers of stress and inflammation in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients: a network analysis. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(10):7109–21.

Murri MB, et al. The facets of psychopathology in patients with cancer: cross-sectional and longitudinal network analyses. J Psychosom Res. 2023;165: 111139.

Lin Y, et al. A network analysis of self-reported psychoneurological symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Cancer. 2022;128(20):3734–43.

Cai T, et al. Cancer-related symptoms among young and middle-aged women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer: application of latent class analysis and network analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;63: 102287.

Cai T, et al. Identification of age differences in cancer-related symptoms in women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer in China. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):100.

Harnas SJ, Knoop H, Booij SH, Braamse AMJ. Personalizing cognitive behavioral therapy for cancer-related fatigue using ecological momentary assessments followed by automated individual time series analyses: a case report series. Internet Interv. 2021;25: 100430.

Henneghan A, Wright ML, Bourne G, Sales AC. A cross-sectional exploration of cytokine-symptom networks in breast cancer survivors using network analysis. Can J Nurs Res. 2021;53(3):303–15.

de Rooij BH, et al. Symptom clusters in 1330 survivors of 7 cancer types from the PROFILES registry: a network analysis. Cancer. 2021;127(24):4665–74.

Bickel, E.A., et al., Looking at individual symptoms: the dynamic network structure of depressive symptoms in cancer survivors and their preferences for psychological care. J Cancer Surviv, 2022: p. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01246-4

Bootsma TI, et al. Using smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment and personalized feedback for patients with chronic cancer-related fatigue: a proof-of-concept study. Internet Interv. 2022;30: 100568.

Bergsneider BH, et al. Discovery of clinical and demographic determinants of symptom burden in primary brain tumor patients using network analysis and unsupervised clustering. Neurooncol Adv. 2023;5(1):vdac188.

Neijenhuijs KI, et al. Symptom clusters among cancer survivors: what can machine learning techniques tell us? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):166.

Schellekens MPJ, et al. Exploring the interconnectedness of fatigue, depression, anxiety and potential risk and protective factors in cancer patients: a network approach. J Behav Med. 2020;43(4):553–63.

Hartung TJ, et al. Frequency and network analysis of depressive symptoms in patients with cancer compared to the general population. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:295–301.

Sharpley CF, Christie DRH, Arnold WM, Bitsika V. Network analysis of depression in prostate cancer patients: implications for assessment and treatment. Psychooncol. 2023;32(3):368–74.

Röttgering, J.G., et al., Symptom networks in glioma patients: understanding the multidimensionality of symptoms and quality of life. J Cancer Surviv, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01355-8

van der Stap L, et al. The feasibility of a Bayesian network model to assess the probability of simultaneous symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):22295.

Kossakowski JJ, et al. The application of a network approach to Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL): introducing a new method for assessing HRQoL in healthy adults and cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(4):781–92.

Airaksinen J, Gluschkoff K, Kivimäki M, Jokela M. Connectivity of depression symptoms before and after diagnosis of a chronic disease: a network analysis in the U.S. Health and Retirement Study. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:230–4.

Yang Y, et al. Network connectivity between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients. J Affect Disord. 2022;309:358–67.

Bobevski I, et al. Demoralisation and its link with depression, psychological adjustment and suicidality among cancer patients: a network psychometrics approach. Cancer Med. 2022;11(3):815–25.

Zaza C, Baines N. Cancer pain and psychosocial factors: a critical review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(5):526–42.

Laird BJ, Boyd AC, Colvin LA, Fallon MT. Are cancer pain and depression interdependent? A Syst Rev Psychooncol. 2009;18(5):459–64.

Brown LF, Kroenke K. Cancer-related fatigue and its associations with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):440–7.

Harris CS, et al. Symptom clusters in patients receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022;12(1):10–21.

Ward Sullivan C, Leutwyler H, Dunn LB, Miaskowski C. A review of the literature on symptom clusters in studies that included oncology patients receiving primary or adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(3–4):516–45.

So WKW, et al. Symptom clusters experienced by breast cancer patients at various treatment stages: a systematic review. Cancer Med. 2021;10(8):2531–65.

Neefjes EC, van der Vorst MJ, Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Verheul HM. Aiming for a better understanding and management of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2013;18(10):1135–43.

Burger J, et al. Reporting standards for psychological network analyses in cross-sectional data. Psychol Methods. 2022;28(4):806–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000471.

Guloksuz S, Pries LK, van Os J. Application of network methods for understanding mental disorders: pitfalls and promise. Psychol Med. 2017;47(16):2743–52.

Jim HS, et al. Lagged relationships among sleep disturbance, fatigue, and depressed mood during chemotherapy. Health Psychol. 2013;32(7):768–74.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Caroline Planting from GGZ inGeest for her help and advice in the execution of the literature search.

Funding

Preparation of the manuscript was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant 11839).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceptualized by ED, FL, ML, ATFB, HV, and JD. Title and abstract screening was performed by ED, with validation of FL and JD. Full text selection was performed by ED and FL, with consultation of JD. Data extraction was performed by ED, with validation of FL and consultation of JD. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ED, and all authors were involved in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

No authors have a conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doppenberg-Smit, G.E., Lamers, F., van Linde, M.E. et al. Network analysis used to investigate the interplay among somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01543-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01543-0