Abstract

Purposes

Studies investigating self-reported long-term morbidity in childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are using heterogeneous outcome definitions, which compromises comparability and include (un)treated asymptomatic and symptomatic outcomes. We generated a Dutch LATER core set of clinically relevant physical outcomes, based on self-reported data. Clinically relevant outcomes were defined as outcomes associated with clinical symptoms or requiring medical treatment.

Methods

First, we generated a draft outcome set based on existing questionnaires embedded in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, and Dutch LATER study. We added specific outcomes reported by survivors in the Dutch LATER questionnaire. Second, we selected a list of clinical relevant outcomes by agreement among a Dutch LATER experts team. Third, we compared the proposed clinically relevant outcomes to the severity grading of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

Results

A core set of 74 self-reported long-term clinically relevant physical morbidity outcomes was established. Comparison to the CTCAE showed that 36% of these clinically relevant outcomes were missing in the CTCAE.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

This proposed core outcome set of clinical relevant outcomes for self-reported data will be used to investigate the self-reported morbidity in the Dutch LATER study. Furthermore, this Dutch LATER outcome set can be used as a starting point for international harmonization for long-term outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The vast majority of children diagnosed with cancer nowadays will achieve long-term survival [1, 2]. Those childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are a growing, vulnerable group of individuals who are at risk of developing long-term morbidity due to previous treatment for cancer in early stages of life. Knowledge on the burden of long-term morbidity in CCS, its underlying types of health conditions and its risk factors, has been presented in various studies during the past decades [3,4,5].

In long-term morbidity research in CCS, a broad variety of outcome assessment methods is used. Long-term morbidity outcomes can be assessed by self-reporting via questionnaires [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], by medical evaluation during outpatient clinic visits [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] or by linkage with existing registries such as national hospital discharge registries [35,36,37,38,39]. Authors often include different types and different numbers of organ systems in their calculations of physical long-term morbidity [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Also, incidence or prevalence estimates are often reported without describing which health conditions or organ systems were included in these calculations. Definitions of long-term morbidity outcomes also vary, for example, authors reporting on cardiovascular conditions generally report on heart failure, myocardial infarction, and hypertension, but some also include stroke as a cardiovascular condition [10, 14, 17, 18, 36]. While many authors do not grade the severity of the reported long-term morbidity in CCS, others use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) [40], either in its original form or an adapted version incorporating specific additional outcomes that authors considered missing [41,42,43]. This lack of uniformity in types of outcomes, outcome definitions, and outcome grading—even among studies that use similar data ascertainment methods—limits interpretation, comparability, and generalizability of studies investigating the burden of long-term morbidity in CCS. Furthermore, the described outcomes in current studies include asymptomatic and symptomatic outcomes with or without treatment. To get a better insight in the overall burden for survivors, the Dutch LATER questionnaire study would like to evaluate only outcomes that are symptomatic and/or requiring medical treatment.

The aim of this study is to develop a set of self-reported long-term physical outcomes that are clinically relevant for CCS, defined as morbidities with clinical symptoms and/or requiring medical treatment, to investigate the burden of morbidity in the Dutch LATER questionnaire study.

Methods

Development of draft outcomes set based on existing questionnaires and input from survivors

Three commonly used questionnaires addressing long-term morbidity in childhood cancer survivors were used for this article: the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group—Long-Term Effects After Childhood Cancer (Dutch LATER) study questionnaire which was used in the Dutch LATER research program [44], the Northern American Childhood Cancer Survivor Study questionnaire [45], and the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study questionnaire [46]. See Supplementary Tables S1–S3 for the respective items. In long-term morbidity research, the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study questionnaire was used either in its original form [6,7,8, 10, 12,13,14,15, 18, 20, 22, 24, 47,48,49,50,51,52] or adapted by authors for their own specific study [9, 21, 53]. The questionnaires covered multiple dimensions of late side effects. For this article, we focused on self-reported physical outcomes, covered by the questionnaire sections on medical history and health conditions.

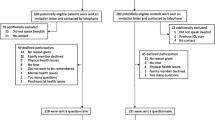

The methods of comparing the three long-term morbidity questionnaires and selection of self-reported long-term physical outcomes for CCS are summarized in Fig. 1. We condensed all outcomes from the three questionnaires into 15 categories. All but two were defined per organ system, i.e., conditions of the eye, ear, speech, cardiac, vascular, pulmonary, gastro-intestinal, hepatic, renal and urinary tract, endocrine, musculoskeletal, neurologic conditions, and other conditions. In addition, surgical procedures and malignancies were considered (Supplementary Table S4). We listed the concordances and discordances in outcomes embedded in the three aforementioned questionnaires.

The draft outcome set consisted of a selection of (concordant and discordant) outcomes. Next, we reviewed all health conditions that were reported in the open text fields by CCS participating in the Dutch LATER questionnaire study and added these outcomes to the draft outcome set by outcome category. Temporary or self-limiting morbidities, for example, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and runner’s knee, were not considered as potential outcomes due to their transient nature and were, therefore, removed from the draft outcome set. Childhood cancer-directed surgeries impacting CCS in later life, for example, limb amputation which results in a lifelong disability or removal of an eye which results in lifelong complications, were added to the draft outcome list. Also, obesity and underweight were added because they were no self-reported outcome in the aforementioned questionnaires.

Selection of self-reported long-term physical outcomes for CCS

The draft outcome set was reviewed in detail by the Dutch LATER experts team, which comprised a multidisciplinary team of late effects clinicians (pediatric oncology and medical oncology), late effects researchers, a pediatric endocrinologist, and a survivor representative, all of whom are involved in the late effects research. The experts team focused on health conditions that were relevant for childhood cancer survivors, i.e., health conditions that influence their daily life, either by resulting in symptoms or by requiring medical treatment. A proposal for a core outcome set was established by agreement by two authors (N.S. and L.F.), which was discussed by the experts team in a phone meeting. During this meeting, agreement was established regarding a final core set, containing all outcomes deemed relevant for survivors.

Subsequently, for each outcome in the core set, definitions for clinical relevance were established by three authors (N.S., L.F., and L.K.), based on outcome-specific (potential) clinical symptoms and/or (potential) medical treatment. For obesity and underweight in adults, clinical relevance was defined according to the definitions used by the World Health Organization. These definitions were discussed by the experts team by e-mail, until agreement was reached for all clinical relevance criteria.

Comparison between CTCAE and the new Dutch LATER core outcome set

The CTCAE, originally developed to score acute treatment toxicities [40, 54], is commonly used to grade the severity of outcomes in survivorship studies. This terminology comprises a 5-point grading scale for many adverse events, which are defined as unfavorable and unintended signs, symptoms, or disease, associated with the use of medical treatment. Severity grades rank from 1 (mild, asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated) to 5 (death related to adverse event) [40]. To gain insight in the agreement between our newly defined outcome set and CTCAE grading, we added the CTCAE grade based on version 4.03 corresponding to our outcome definition for every proposed physical long-term morbidity outcome. Recently, researchers from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE) adjusted the CTCAE criteria to grade long-term morbidity in their cohort for which data was obtained during clinical assessment using multiple diagnostic modalities. To get insight in concordance between the CTCAE outcomes and the Dutch LATER core outcome set, we compared the different lists of outcomes.

Results

Selection of self-reported long-term physical outcomes of clinical relevance

The process of selection of self-reported clinically relevant physical long-term physical outcomes, as displayed in Fig. 1, resulted in a core outcome set consisting of 74 proposed outcomes. The experts team decided on re-categorizing surgical procedures within their respective organ system and did not consider conditions of speech as clinically relevant. Therefore, the 15 initial outcome categories were re-categorized into 13 proposed main organ system categories: conditions of the eye, ear, cardiac, vascular, respiratory, gastro-intestinal, hepatobiliary tract, renal and urinary tract, endocrine, musculoskeletal, nervous system conditions, other conditions, and neoplasms (see Table 1).

Agreement between the newly defined core outcome set and the CTCAE grading

For each outcome, the minimum CTCAE grades that correspond with our criteria for clinical relevance are shown in Supplementary Table S5. In all, 27 out of 74 (36%) outcomes cannot be graded according to CTCAE because they are not present in the CTCAE as a separate entity. This group of outcomes can be categorized into three subgroups. First, it comprised certain surgeries of which the LATER experts team agreed upon clinical relevance (n = 18), because they influence CCS’s daily life either by having medical consequences (e.g., splenectomy or organ transplantations) or by having cosmetic consequences (e.g., eye enucleation or limb amputation). Second, it comprised blindness and deafness, which are included in the CTCAE not as a specific outcome but as grading scale for several specific other eye and ear/nose/throat outcomes. The LATER experts team agreed that regardless of the underlying pathophysiological mechanism, blindness and deafness were both clinical relevant outcomes that should be included in the core outcome set. Third, specific outcomes that were not present as separate entities in the CTCAE were reported by CCS in the Dutch LATER questionnaire and were perceived as clinically relevant by the experts team (n = 7): aortic aneurysm, liver cirrhosis, tubular dysfunction of the kidneys, prolactinoma, polycystic ovarian syndrome, underweight, and pituitary dysfunction.

Of the remaining 48 conditions, 11 (15%) fulfilled the definition for conditions with a CTCAE grade 3, that is, severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening. For 27 (36%) conditions, our criteria for clinical relevance corresponded with a CTCAE grade 2, moderate severity. For nine (12%) conditions (decreased pulmonary function, proteinuria, chronic kidney disease, precocious puberty, diabetes mellitus, ischemic cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, epilepsy, and headache), it was not possible to define the corresponding CTCAE grade for our established clinical relevance criteria, because additional clinical information was needed for CTCAE-based grading. Comparison to the SJLIFE-based grading showed that 34 conditions from our core set were not present in SJLIFE (46%) and additional information was needed for grading of 5 conditions (7%). A total of 23 clinically relevant conditions corresponded with SJLIFE grade 2 (31%) and two clinically relevant conditions (adrenal insufficiency and growth hormone deficiency) corresponded with SJLIFE grade 1 (3%).

Discussion

We present a proposal for a core set of 74 self-reported long-term physical outcomes of clinical relevance in survivors of childhood cancer. By comparison of existing survivorship questionnaires and by reviewing every specific morbidity reported by CCS in the open text fields in our Dutch nationwide questionnaire study, we followed an innovative method which focuses on outcomes that are clinically relevant for the survivor, due to the fact that its presence influences daily life. Our outcome set will be used for investigating the burden of long-term morbidity in the Dutch LATER questionnaire study. This set can also be used for international harmonization of a uniform core outcome set for long-term morbidity in CCS, to facilitate worldwide collaboration in late effects research.

Compared with other grading scales used for long-term morbidity research in CCS, the newly developed Dutch LATER core outcome set differs on three important key points. First, this core outcome set was designed with the single purpose of investigating self-reported long-term morbidity in childhood cancer survivors, by combining existing questionnaires and outcomes reported by survivors. Second, we selected outcomes describing morbidity with clinical symptoms or requiring medical treatment, the so-called clinically relevant outcomes. Third we included outcomes where the treatment for childhood cancer caused direct damage that had persistent impact for the survivor also in later life, for example, limb amputation which results in a lifelong disability or removal of an eye which results in lifelong complications. Because the CTCAE criteria were originally designed for grading acute adverse events during adult cancer trials [54], the current CTCAE version 4.03 [40] does not cover the complete spectrum of long-term morbidity that CCS might encounter [42]. Several authors have already stated that relevant outcomes were missing for CCS and use adapted versions [41,42,43]. Comparison of our core set of long-term self-reported physical outcomes to the commonly used CTCAE showed that 36% of the outcomes were not present in the CTCAE. Moreover, CTCAE does not incorporate self-reported data to assess long-term morbidity [42]. For nine out of the 48 conditions that were present in the CTCAE, we could not perform severity grading because detailed additional clinical information was needed for appropriate grading, which was not available from current questionnaires and is often too complicated to directly ask patients in a questionnaire. Although often only health conditions grade 3 and higher are included when studying severe physical long-term morbidity in CCS, our results show that many grade 2 conditions will have consequences for a survivor because of symptoms or needed treatment. From our core outcome set, up to 27 clinically relevant outcomes corresponded with CTCAE grade 2, for example, several endocrine deficiencies that require chronic medication use, and would have been missed in such studies. Comparison to the SJLIFE adapted CTCAE for grading of clinically ascertained data showed that more of our core outcomes were missing and that 24 clinically relevant conditions corresponded to grade 2 or even grade 1. Hence, our results support previous authors, concluding that the CTCAE in its current form is not optimal to grade severity of (self-reported) long-term physical morbidity outcomes for CCS [41,42,43]. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive proposal to define a core outcome set for self-reported long-term physical outcomes in CCS. A strength of this study is that we focused on clinical relevance for CCSA and a limitation is that we were not yet able to incorporate the prioritization of outcomes by survivors. This can be the focus of future research. Also, because the purpose of this core outcome set was facilitating the investigation of physical long-term morbidity in the Dutch LATER cohort, the proposed outcome definitions reflect the agreement among the Dutch LATER experts team only. To overcome any subjectivity in outcomes used by various childhood cancer survivorship research groups, we advocate international harmonization of a core outcome set for physical long-term morbidity in childhood cancer survivors. A uniform global core outcome set is highly needed to enable comparison of future long-term morbidity studies, to uniformly evaluate survivorship care and to facilitate collaboration within survivorship research. The International Guideline Harmonization Group [55] started an initiative to develop a harmonized outcome set by a Delphi method. This will facilitate international collaboration and data pooling.

In conclusion, we propose a Dutch LATER core set of self-reported long-term physical outcomes of clinical relevance for CCS that will be used to investigate the burden of long-term morbidity in childhood cancer survivors from the Dutch LATER questionnaire study. We advocate to start international discussion and research to harmonize long-term physical morbidity outcomes that are clinically relevant for CCS.

References

Pritchard-Jones K, Kaatsch P, Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller CA, Coebergh JW. Cancer in children and adolescents in Europe: developments over 20 years and future challenges. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(13):2183–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.06.006.

Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T, Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007: results of EUROCARE-5--a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70548-5.

Oeffinger KC, van Leeuwen FE, Hodgson DC. Methods to assess adverse health-related outcomes in cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(10):2022–34. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0674.

Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJ, Heinen RC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2705–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.24.2705.

Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Mulrooney DA, Chemaitilly W, Krull KR, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2371–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6296.

Armenian SH, Sun CL, Kawashima T, Arora M, Leisenring W, Sklar CA, et al. Long-term health-related outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer treated with HSCT versus conventional therapy: a report from the bone marrow transplant survivor study (BMTSS) and childhood cancer survivor study (CCSS). Blood. 2011;118(5):1413–20. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-01-331835.

Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Huang S, Ness KK, Leisenring W, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(13):946–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djp148.

Essig S, Li Q, Chen Y, Hitzler J, Leisenring W, Greenberg M, et al. Risk of late effects of treatment in children newly diagnosed with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(8):841–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70265-7.

Friedman DN, Chou JF, Oeffinger KC, Kleinerman RA, Ford JS, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic medical conditions in adult survivors of retinoblastoma: results of the retinoblastoma survivor study. Cancer. 2016;122(5):773–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29704.

Ginsberg JP, Goodman P, Leisenring W, Ness KK, Meyers PA, Wolden SL, et al. Long-term survivors of childhood Ewing sarcoma: report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(16):1272–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq278.

Ishida Y, Honda M, Ozono S, Okamura J, Asami K, Maeda N, et al. Late effects and quality of life of childhood cancer survivors: part 1. Impact of stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2010;91(5):865–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-010-0584-y.

King AA, Seidel K, Di C, Leisenring WM, Perkins SM, Krull KR, et al. Long-term neurologic health and psychosocial function of adult survivors of childhood medulloblastoma/PNET: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Neuro-Oncology. 2017;19(5):689–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/now242.

Laverdiere C, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Nathan PC, Gurney JG, Stovall M, et al. Long-term outcomes in survivors of neuroblastoma: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(16):1131–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djp230.

Liu Q, Leisenring WM, Ness KK, Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Yasui Y, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in adverse outcomes among childhood cancer survivors: the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1634–43. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3567.

Marina NM, Liu Q, Donaldson SS, Sklar CA, Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of adult survivors of Ewing sarcoma: a report from the childhood Cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2551–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30627.

Michel G, Greenfield DM, Absolom K, Ross RJ, Davies H, Eiser C. Follow-up care after childhood cancer: survivors’ expectations and preferences for care. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(9):1616–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.02.026.

Mody R, Li S, Dover DC, Sallan S, Leisenring W, Oeffinger KC, et al. Twenty-five-year follow-up among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Blood. 2008;111(12):5515–23. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-10-117150.

Mulrooney DA, Dover DC, Li S, Yasui Y, Ness KK, Mertens AC, et al. Twenty years of follow-up among survivors of childhood and young adult acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2008;112(9):2071–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23405.

Nagarajan R, Kamruzzaman A, Ness KK, Marchese VG, Sklar C, Mertens A, et al. Twenty years of follow-up of survivors of childhood osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2011;117(3):625–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25446.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa060185.

Saha A, Salley CG, Saigal P, Rolnitzky L, Goldberg J, Scott S, et al. Late effects in survivors of childhood CNS tumors treated on head start I and II protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(9):1644–52; quiz 53-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25064.

Schultz KAP, Chen L, Chen Z, Kawashima T, Oeffinger KC, Woods WG, et al. Health conditions and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia comparing post remission chemotherapy to BMT: a report from the children's oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(4):729–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24881.

Stevens MC, Mahler H, Parkes S. The health status of adult survivors of cancer in childhood. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(5):694–8.

Termuhlen AM, Tersak JM, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Stovall M, Weathers R, et al. Twenty-five year follow-up of childhood Wilms tumor: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(7):1210–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.23090.

Armstrong AE, Danner-Koptik K, Golden S, Schneiderman J, Kletzel M, Reichek J, et al. Late effects in pediatric high-risk Neuroblastoma survivors after intensive induction chemotherapy followed by myeloablative consolidation chemotherapy and triple autologous stem cell transplants. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40(1):31–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000848.

Blaauwbroek R, Groenier KH, Kamps WA, Meyboom-de Jong B, Postma A. Late effects in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the need for life-long follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(11):1898–902. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm336.

Faraci M, Barra S, Cohen A, Lanino E, Grisolia F, Miano M, et al. Very late nonfatal consequences of fractionated TBI in children undergoing bone marrow transplant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(5):1568–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.031.

Lannering B, Marky I, Lundberg A, Olsson E. Long-term sequelae after pediatric brain tumors: their effect on disability and quality of life. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1990;18(4):304–10.

Oeffinger KC, Eshelman DA, Tomlinson GE, Buchanan GR, Foster BM. Grading of late effects in young adult survivors of childhood cancer followed in an ambulatory adult setting. Cancer. 2000;88(7):1687–95.

Parigi GB, Beluffi G, Corbella F, Matteotti C, Ramella B, Bragheri R. Long-term follow-up in children treated for retroperitoneal malignant tumours. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13(4):240–4. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-42243.

Spunberg JJ, Chang CH, Goldman M, Auricchio E, Bell JJ. Quality of long-term survival following irradiation for intracranial tumors in children under the age of two. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(6):727–36.

Taylor RE. Morbidity from abdominal radiotherapy in the first United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group Wilms’ Tumour study. United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1997;9(6):381–4.

Von der Weid N, Beck D, Caflisch U, Feldges A, Wyss M, Wagner H. Standardized assessment of late effects in long-term survivors of childhood cancer in Switzerland. Int J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;3(6):483–90.

Von der Weid N. Swiss pediatric oncology group. Late effects in long-term survivors of all in childhood: experiences from the SPOG late effects study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131(13–14):180–7.

Chao C, Xu L, Bell E, Cooper R, Mueller L. Long-term health outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed between 1990 and 2000 in a large US integrated health care system. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38(2):123–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000492.

Gunn ME, Malila N, Lahdesmaki T, Arola M, Gronroos M, Matomaki J, et al. Late new morbidity in survivors of adolescent and young-adulthood brain tumors in Finland: a registry-based study. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17(10):1412–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nov115.

de Fine LS, Rugbjerg K, Gudmundsdottir T, Bonnesen TG, Asdahl PH, Holmqvist AS, et al. Long-term inpatient disease burden in the adult life after childhood cancer in Scandinavia (ALiCCS) study: a cohort study of 21,297 childhood cancer survivors. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5):e1002296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002296.

Font-Gonzalez A, Feijen E, Geskus RB, Dijkgraaf MGW, van der Pal HJH, Heinen RC, et al. Risk and associated risk factors of hospitalization for specific health problems over time in childhood cancer survivors: a medical record linkage study. Cancer Med. 2017;6(5):1123–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1057.

Sieswerda E, Font-Gonzalez A, Reitsma JB, Dijkgraaf MG, Heinen RC, Jaspers MW, et al. High hospitalization rates in survivors of childhood cancer: a longitudinal follow-up study using medical record linkage. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159518. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159518.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0. Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2009.

Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, Baassiri M, Eissa H, Yeo F, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study (SJLIFE). Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2569–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31610-0.

Hudson MM, Ehrhardt MJ, Bhakta N, Baassiri M, Eissa H, Chemaitilly W, et al. Approach for classification and severity grading of long-term and late-onset health events among childhood Cancer survivors in the St. Jude lifetime cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(5):666–74. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0812.

Erman N, Todorovski L, Jereb B. Late somatic sequelae after treatment of childhood cancer in Slovenia. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:254. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-254.

Teepen JC, van Leeuwen FE, Tissing WJ, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van der Pal HJ, et al. Long-term risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms after treatment of childhood cancer in the DCOG LATER study cohort: role of chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(20):2288–98. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6902.

CCRF Epidemiology Research Unit, Division of Epidemiology/Clinical Research, Department of Pediatrics. Long-term follow-up study of individuals treated for cancer, leukemia, tumor or similar illness. https://ccss.stjude.org/content/dam/en_US/shared/ccss/documents/survey/survey-baseline.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2020.

Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, University of Birmingham. Study of people treated for cancer, leukaemia, tumour or similar illness in childhood. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/haps/projects/cancerPH/bccss/completeqm.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2020.

Goldsby RE, Stratton KL, Raber S, Ablin A, Strong LC, Oeffinger K, et al. Long-term sequelae in survivors of childhood leukemia with down syndrome: a childhood cancer survivor study report. Cancer. 2018;124(3):617–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31065.

Hudson MM, Oeffinger KC, Jones K, Brinkman TM, Krull KR, Mulrooney DA, et al. Age-dependent changes in health status in the childhood cancer survivor cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(5):479–91. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4863.

Nagarajan R, Kamruzzaman A, Ness KK, Marchese VG, Sklar C, Mertens A, et al. Twenty years of follow-up of survivors of childhood osteosarcoma: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2011;117(3):625–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25446.

Wells EM, Ullrich NJ, Seidel K, Leisenring W, Sklar CA, Armstrong GT, et al. Longitudinal assessment of late-onset neurologic conditions in survivors of childhood central nervous system tumors: a childhood cancer survivor study report. Neuro-Oncology. 2018;20(1):132–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox148.

Hawkins MM, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Taylor AJ, et al. The British childhood cancer survivor study: objectives, methods, population structure, response rates and initial descriptive information. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5):1018–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21335.

Wong KF, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Guha J, Fidler MM, Kelly J, et al. Risk of adverse health and social outcomes up to 50 years after Wilms tumor: the British childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1772–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.4344.

Kenney LB, Nancarrow CM, Najita J, Vrooman LM, Rothwell M, Recklitis C, et al. Health status of the oldest adult survivors of cancer during childhood. Cancer. 2010;116(2):497–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24718.

Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Clauser SB, Minasian LM, Dueck AC, et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(9). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju244.

Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, Bhatia S, Landier W, Levitt G, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the international late effects of childhood Cancer guideline harmonization group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(4):543–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24445.

Funding

Nina Streefkerk is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant No. UVA2014-6805).

Cecile Ronckers is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant No. UVA2012-5517).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design and data collection of the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. NS, EF, MvdHL, JK, WT, RM, and LK drafted the manuscript and all other authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data availability

Data used for this study was not publicly available.

Ethical statement

The LATER questionnaire study was declared exempt from review of medical intervention research by the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center of Amsterdam and by the boards of all participating centers. All LATER questionnaire participants gave written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 1.36 mb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Streefkerk, N., Tissing, W.J.E., van der Heiden-van der Loo, M. et al. The Dutch LATER physical outcomes set for self-reported data in survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 14, 666–676 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00880-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00880-0