Abstract

Purpose

Previous research has established that treatments for cancer can result in short- and long-term effects on sexual function in adult cancer patients. The purpose was to investigate patient-reported physical and psychosexual complications in adolescents and young adults after they have undergone treatment for cancer.

Methods

In this population-based study, a study-specific questionnaire was developed by a method used in several previous investigations carried out by our research group, Clinical Cancer Epidemiology. The questionnaire was developed in collaboration with adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (15–29 years) and validated by professionals from oncology units, midwives, epidemiologists, and statisticians. The topics covered in the questionnaire were psychosocial health, body image, sexuality, fertility, education, work, and leisure. The web-based questionnaire was sent to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors and matched controls in Sweden.

Results

In this study, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (15–29 years) showed low satisfaction regarding sexual function compared to controls (P < 0.01). Female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors had a statistically significant lower frequency of orgasm during sexual activity than the controls (P < 0.01). Male adolescent and young adult cancer survivors had statistically significant lower sexual desire than the controls (P = 0.04).

Conclusions

We found that adolescent and young adult cancer survivors perceived themselves as being less satisfied with their sexual function than matched population-based controls.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Adolescent and young adult cancer survivors need psychological rehabilitation support from the health care profession during and after cancer treatment to help them to reduce their reported poor sexual function to enhance a good sexual quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer in adolescents and young adults, AYA (ages 15–29) is less common than in older adults. Research has been conducted on the AYA population only in the past decade [1, 2]. It has earlier been established that treatments for cancer can result in short- and long-term effects on sexual function in adult cancer patients. The long-term effects on sexual function are related both to diagnosis and treatment modality for each individual [3]. Common physical sexual problems after cancer treatment are low desire, genital pain, decreased lubrication, erection difficulties, and arousal difficulties [4,5,6,7]. Knowledge on treatment-related sexual dysfunction in adults needs to be complemented on AYA sexual function after cancer treatment [8]. Adolescence and young adulthood is a time in life when the psychosexual identity is developed and romantic relationships evolve. Therefore, there may be negative effects on sexual function among AYA cancer survivors who have been treated for cancer during these vulnerable years. A few studies on AYA cancer patients regarding sexual function have been conducted previously, presenting mixed findings on sexual function and satisfaction within the AYA group [9,10,11]. Most of the studies have not included a control group. In a study which included a control group, no significant difference was found between AYA testicular cancer survivors and the controls when it came to sexual satisfaction [12]. However, in a study on women surviving Hodgkin’s disease, lower satisfaction with sexual function was reported than in the control group [13].

In this study, we present patient-reported physical and psychological sexual complications in the AYA group after cancer treatment. The aim of this study has been to explore whether AYA cancer patients have physical and psychological symptoms affecting sexual function and, if so, to determine whether or not these symptoms differ from AYA in general.

Methods

Study population

Six hundred and sixty AYA cancer survivors were identified from four of the register holders belonging to the population-based Swedish National Cancer Registry, namely the Regional Cancer Centres for the north, west, southeast, and central regions of Sweden. The former cancer patients had been treated for cancer when aged between 15 and 29 during 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2011. In this study, we decided on the inclusion of 15–29 year olds in the AYA age group, as was current in Europe at the start of this study [14]. During the study, they were alive and at least 1 year post treatment. All malignant diagnoses were included based on ICD version 10, neoplasms. Participants were eligible for the study if they (1) understood the Swedish language, (2) were not undergoing treatment for cancer, (3) had a listed phone number, and (4) were functionally/cognitively able to answer the questionnaire. Controls were randomly identified from the Swedish National Population Registry and matched by age, gender, and place of residence. The Regional Cancer Centers delivered the names and addresses as one cohort, without information on whether they were patients or controls. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, Sweden, granted ethical approval for this study with the reference number 691-13 and additional reference number 944-14.

Questionnaire

A study-specific questionnaire was constructed, based on a 24-month qualitative phase, clinical experience, and a method established by the research group at the Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology [15]. The method has been used in more than 20 data collections focusing on cancer and survivorship [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The study-specific questionnaire was validated in several steps including comments from experts, researchers, clinicians, and patients to test the comprehension of the questions and to see if the main specific areas were covered. Ten former cancer patients tested the revised questionnaire by face-to-face validation, i.e., answering the questions in the presence of the interviewer and discussing unclear questions. A revised draft was constructed, and a pilot study was carried out with 28 cancer survivors, more than 5 years post cancer treatment. The overall participation rate in the pilot study was 71%, and the pilot study resulted in minor improvements to the questionnaire.

The primary questions in the web questionnaire asked interviewees whether they had a cancer diagnosis and to state their gender. The results from these two questions directed each respondent to the questionnaire relevant to her or him. The questionnaire included 98 questions on demographics, quality of life, well-being, psychosocial health, social life, education, work, leisure, fertility, body image, and sexuality. This paper focuses on variables of the self-perceived sexual function and the remaining results have been or will be analyzed elsewhere. Questions included in this study were as follows, for women: superficial dyspareunia: “Have you experience pain in the mucous membranes or in the opening of vagina during sexual intercourse or other sexual activities, the last six months?” and deep dyspareunia: “Have you had pain of the depth of vagina and inside the pelvis during sexual intercourse or in other sexual activites, the last six months?” “Have you experienced sufficient lubrication during the past six months?” with multiple-choice answers: “No,” “Yes, a little,” “Yes, moderate,” or “Yes, a lot.” In addition, for men: “Have you experienced difficulties getting an erection during the past month?” “Have you experienced ejaculation during orgasm during the past month?” “Have you experienced premature ejaculation during the past month?” with multiple-choice answers: “No,” “Yes, a little,” “Yes, moderate,” or “Yes, a lot.” Followed by questions for men and women: “Have you experienced orgasm during the past month?” with multiple-choice answers: “Not at all,” “Less than once a month,” “One to two times a month,” “Three to four times a month,” “One to two times a week,” or “More than three times a week.” “Have you had desire for sex during the past month?” with multiple-choice answers: “No,” “Yes, a little,” “Yes, moderate,” or “Yes, a lot.” Variables used in the analysis were age; relationship status (married/co-habitation, in a relationship, single); feeling attractive during the past 6 months (yes very much, moderately, a little, or no); having negative perception of your body (yes very much, moderately, a little, or no); feeling tired during daytime (never, occasionally, 50% of the time, more than 50% of the time, every day); depression (no, yes or I do not know); anxiety (a scale from 1 = never to 7 = always); having children (yes or no); being infertile (yes, no, do not know); educational level (university, primary and secondary school); and diagnosis group (leukemia, lymphoma, testicular cancer, breast cancer, bone cancer, CNS tumors, gynecological cancer, skin cancer, thyroid cancer and misc./other). All the response alternatives have been validated in previous studies conducted by the research group [20, 22,23,24]. We modified questions regarding participation in this study from similar questions in previous research [25,26,27].

Data collection

An introductory letter was sent to former patients and controls with information on the study and a statement that participation would be voluntary and could be ceased without explanation or repercussions at any time. One to 2 weeks later, an interviewer phoned each prospective informant.

The informants gave their informed consent by giving the interviewer their e-mail addresses. In an e-mail, each participant then received a personal username and password for the web questionnaire. After 2 weeks, the participants received a thank-you e-mail to show appreciation for their participation and to serve as a reminder, for those who needed one. A few weeks later, the interviewer phoned those who had not completed the questionnaire. The answers to the web-based questionnaire were automatically sent to a database, and each questionnaire was given a number for identification to maintain anonymity. Participants received information regarding the research group and were given contact information (an around-the-clock telephone number and an e-mail address) in case they needed to talk to someone or had a question.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were undertaken using SPSS version 23 and SAS 9.4 for Windows.

Sociodemographic and descriptive characteristics were compared between the survivors and controls using the chi2 test for categorical variables. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test potential differences between groups with respect to prevalence of scars and attractiveness. Outcome measures were presented as a relative risk and odds ratio. A primary regression analysis was conducted in the survivor group of men and women, respectively, with the dependent variable being satisfaction with sexual function and the independent variables being age (age groups younger < 24 years, middle 25–30 years, and older > 31 years); relationship status (in a relationship/not in a relationship); feeling attractive during the past 6 months (dichotomized to no or yes); feeling tired during daytime (occasionally, or 50% and more of the time); having orgasm (dichotomized to seldom = 1–2 or often = 3–4); desire for sex (dichotomized to no = 1 or yes = 2–4); depression (no, yes, or I do not know); anxiety (a scale from1 = never to 7 = always, dichotomized to 1–3 = never, and 4–7 = always); having negative perception of your body (dichotomized to no or yes); being infertile (no, yes, do not know); having children (yes or no); and educational level (dichotomized to higher education = university or lower education = primary and secondary school). The level of significance was set at P = 0.05.

Results

From November 2014 to May 2016, 721 of the eligible participants (patients and controls) were alive and included in the study. Altogether 540 (74%) participants completed the questionnaire. A total of 122 participants declined participation, and 67 did not complete the questionnaire. The study group consisted of 285 survivors of cancer during adolescence and young adulthood, with the mean age of 28 (range 19–35), and the control group consisted of 255 participants with the mean age of 28 (range 19–36). There were no differences between the groups, except regarding education, where the controls had a significantly higher educational level than the cancer survivors. Further information on demographics and self-reported clinical characteristics is presented in Table 1.

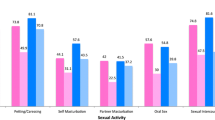

In this study, AYA cancer survivors felt less satisfaction regarding sexual function than the controls, P < 0.01 (Table 2).

Female AYA cancer survivors

Female AYA cancer survivors had a statically significant lower frequency of orgasm during sexual activity than the controls (P < 0.01) (Table 3). Of female AYA cancer survivors, 15% reported having superficial dyspareunia and 25% little or no lubrication (Table 3). However, there were no statistically significant differences between female AYA cancer survivors and the controls regarding these physical problems (Table 3). Additionally, female AYA cancer survivors who had a partner felt less confidence than the controls in their partner as a reliable friend (Table 2). There was no difference in the desire for sex between female AYA cancer survivors and the controls (Table 3). In a primary univariate regression analysis of possible confounders, the following factors were associated with low satisfaction with sexual function in female AYA cancer survivors: low desire for sex, lower frequency of orgasms, feeling unattractive, depression, and lower education. In a secondary analysis where we adjusted all significant confounders in the primary analysis in a multivariable logistic regression model, depression (OR 3.5; 95% CI 1.4–8.9) was the only factor predicting feelings of low satisfaction with sexual function (Table 4).

Male AYA cancer survivors

Male AYA cancer survivors reported a statistically significant lower sexual desire than the controls (P = 0.04) (Table 3). Of male AYA cancer survivors, approximately 10% reported having problems in getting an erection, 10% reported frequently having premature ejaculation, 15% reported not always ejaculating during orgasm, and 10% reported having orgasm less than once a month (Table 3). However, there were no statistically significant differences between male AYA cancer survivors and the controls regarding physical problems (Table 3). In a primary univariate regression analysis of possible confounders, the following factors were associated with low satisfaction with sexual function in male AYA cancer survivors: erectile problems, premature ejaculation, feeling unattractive, depression, and younger ages. In a secondary analysis where we adjusted all significant confounders from the primary analysis in a multivariable logistic regression model, erectile problems (OR 20.7; 95% CI 2.8–152.7) constituted the only factor predicting low feeling of satisfaction with sexual function (Table 4).

Discussion

The results from our study show that AYA cancer survivors experience less sexual satisfaction compared to controls. In addition, female AYA cancer survivors reported lower frequency of orgasm than the controls and male cancer survivors reported lower desire for sex than the controls.

A few studies have previously established that AYA cancer survivors have reported certain sexual concerns [10, 28, 29]. Nevertheless, several of these previous studies had no control groups, which may have risked excluding sexual difficulties found in the general population. This study contributes new knowledge in this field, since the AYA cancer survivors in this study actually do express lower satisfaction with their sexual functions than the control group of the study. However, the results in this study are incongruent with some previous studies that included a control group but reported no significant difference between the study groups and the controls [12, 30].

In this study, we also found that female AYA cancer survivors report lower frequency of orgasm than the controls. In previous studies, there have been mixed results concerning the frequency of orgasm. In one study on Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients, no differences were found between cancer survivors and controls, while another study not including a control group did found difficulties in achieving orgasm post brain tumor surgery [13, 31]. Having less frequent orgasm orgasms could lead to feeling less satisfied with sexual function. In studies on cancer survivors, one long-term effect is peripheral neuropathy in the extremities, and among female diabetes patients, having vascular damage and neuropathy may result in decreased genital blood flow and cause genital arousal, orgasm [32, 33]. Whether difficulties having less frequent orgasm are due to physical or psychological effects needs further research, including more detailed information on cancer treatment. However, in the multivariable log-binominal regression analysis, frequency of orgasm did not predict low satisfaction with sexual function (Table 4). What did in fact predict low satisfaction with sexual function, in this study, was depression. It is difficult to establish the cause of depression in AYA cancer survivors. Low satisfaction with sexual function could be a cause of depression or vice versa. However, according to previous studies, depression is common post cancer treatment [34,35,36]. Additionally, female AYA cancer survivors report less confidence in their partners as supportive friends, which may well have an impact on satisfaction with sexuality. This is consistent with a previous study on female AYA lymphoma survivors, where feeling unattractive was discussed as cause of guilt for “dragging their partner into the struggle of cancer” another [37]. We may also speculate that this could cause feelings of not being understood or communication problems, as has been reported in previous studies on adult patients with cancer [3].

In this study, male AYA cancer survivors also expressed feelings of low sexual satisfaction, and this is contrary to previous findings where male AYA cancer survivors reported an even higher level of satisfaction with sexual function than controls [12, 38, 39]. Male AYA cancer survivors in this study actually reported a lower desire for sex than the controls did. This has been shown in an earlier study where men reported lower sexual desire post testicular cancer treatment [38]. However, in other studies on male AYA cancer survivors, there were no statistically significant differences regarding sexual desire compared to control groups [12, 38]. Additionally, in the multivariable log-binominal regression analysis in this study, low desire for sex did not predict low satisfaction with sexual function (Table 4). What did in fact predict low satisfaction with sexual function was difficulty in getting erection. This is contrary to previous research on testicular cancer survivors where no differences between AYA survivors and controls were found [12]. In previous research, it has however been established that there is an association between depression and erectile dysfunction [40, 41]. However, depression may cause male AYA cancer survivors to report a higher proportion of erection problems.

In earlier studies, questions have been raised whether not being in a relationship, not having children, or being infertile might result in cancer survivors feeling low satisfaction with their sexual function. [11, 42,43,44]. However, in this study, we could not find any statistically significant association between low satisfaction with sexual function and not being in a relationship, not having children, or being infertile.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, all malignant diagnoses in this specific age group were included in the study which makes the group heterogeneous with regard to types of treatment. However, since cancer in the AYA population is uncommon, including all the different diagnoses is the method most used when researching this population [45]. Secondly, the lack of information in the medical records impeded the comparison of symptoms reported with cancer treatment details. The participants reported their diagnosis and treatment in general terms, e.g., chemotherapy, radiation, but gave no detailed information.

This study has several strengths though, since by using a national population-based registry, with controls selected by age, gender, and place of residence, we believe that the risk of selection-induced problems was minimized. Furthermore, the use of an anonymous, self-reported questionnaire prevented interview-related bias. The participants’ answers may, however, have been influenced by memory-induced problems, since for some participants, several years had passed since their cancer treatment. Nonetheless, this did not affect the response when it came to the sexual concerns they reported when answering the questionnaire. In previous studies, the response rate has been as low as 43%. The high participation rate in this population-based study and inclusion of a control group minimize the risk of systematic errors.

In this study, AYA cancer survivors experienced lower satisfaction than controls regarding sexual function, mainly for psychological rather than physiological reasons. Sexual health is a part of quality of life, and in order to reduce the low satisfaction with sexual function in AYA cancer survivors, there is a need for rehabilitation. Rehabilitation for AYA cancer survivors should be multidisciplinary and include treatment of clinical depression and counseling on sexuality and relationships.

References

Fern L, Davies S, Eden T, Feltbower R, Grant R, Hawkins M, et al. Rates of inclusion of teenagers and young adults in England into National Cancer Research Network clinical trials: report from the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) teenage and young adult clinical studies development group. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(12):1967–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604751.

Bleyer A, Budd T, Adolescents MM. Young adults with cancer: the scope of the problem and criticality of clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;107(7 Suppl):1645–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22102.

Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3712–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915.

Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(4):937–49.

Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, Gilliland FD, Stephenson RA, Eley JW, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000;283(3):354–60.

Gass JS, Onstad M, Pesek S, Rojas K, Fogarty S, Stuckey A, et al. Breast-specific sensuality and sexual function in cancer survivorship: does surgical modality matter? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3133–40. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5905-4.

Hordern A, Street A. Issues of intimacy and sexuality in the face of cancer: the patient perspective. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(6):E11–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000300162.13639.f5.

Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, Leonard M. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(8):814–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1641.

Hoyt MA, McCann C, Savone M, Saigal CS, Stanton AL. Interpersonal sensitivity and sexual functioning in young men with testicular cancer: the moderating role of coping. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(6):709–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9472-4.

Wettergren L, Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, Rubenstein MB, et al. Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: the Aya hope study. Psychooncology. 2016;26:1632–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4181.

Stanton AM, Handy AB, Meston CM. Sexual function in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;12:47–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0643-y.

Dahl AA, Bremnes R, Dahl O, Klepp O, Wist E, Fossa SD. Is the sexual function compromised in long-term testicular cancer survivors? Eur Urol. 2007;52(5):1438–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.046.

Eeltink CM, Incrocci L, Witte BI, Meurs S, Visser O, Huijgens P, et al. Fertility and sexual function in female Hodgkin lymphoma survivors of reproductive age. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(23–24):3513–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12354.

Aben KK, van Gaal C, van Gils NA, van der Graaf WT, Zielhuis GA. Cancer in adolescents and young adults (15-29 years): a population-based study in the Netherlands 1989-2009. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(7):922–33. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.705891.

Olsson M, Jarfelt M, Pergert P, Enskar K. Experiences of teenagers and young adults treated for cancer in Sweden. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(5):575–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2015.03.003.

Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1383–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199905063401802.

Thorsteinsdottir T, Stranne J, Carlsson S, Anderberg B, Bjorholt I, Damber JE, et al. LAPPRO: a prospective multicentre comparative study of robot-assisted laparoscopic and retropubic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45(2):102–12. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365599.2010.532506.

Eilegard A, Kreicbergs U. Risk of parental dissolution of partnership following the loss of a child to cancer: a population-based long-term follow-up. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):100–1. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.247.

Omerov P, Steineck G, Runeson B, Christensson A, Kreicbergs U, Pettersen R, et al. Preparatory studies to a population-based survey of suicide-bereaved parents in sweden. Crisis. 2013;34(3):200–10.

Dunberger G, Lind H, Steineck G, Waldenstrom AC, Nyberg T, Al-Abany M, et al. Self-reported symptoms of faecal incontinence among long-term gynaecological cancer survivors and population-based controls. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(3):606–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.10.023.

Waldenstrom AC, Olsson C, Wilderang U, Dunberger G, Lind H, al-Abany M, et al. Pain and mean absorbed dose to the pubic bone after radiotherapy among gynecological cancer survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(4):1171–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.007.

Stinesen Kollberg K, Waldenstrom AC, Bergmark K, Dunberger G, Rossander A, Wilderang U, et al. Reduced vaginal elasticity, reduced lubrication, and deep and superficial dyspareunia in irradiated gynecological cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):772–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2014.1001036.

Skoogh J, Steineck G, Stierner U, Cavallin-Stahl E, Wilderang U, Wallin A, et al. Testicular-cancer survivors experience compromised language following chemotherapy: findings in a Swedish population-based study 3-26 years after treatment. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(2):185–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2011.602113.

Skoogh J, Ylitalo N, Larsson Omerov P, Hauksdottir A, Nyberg U, Wilderang U, et al. 'A no means no'--measuring depression using a single-item question versus Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS-D). Ann Oncol. 2010;21(9):1905–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq058.

Dunberger G, Thulin H, Waldenstrom AC, Lind H, Henningsohn L, Avall-Lundqvist E, et al. Cancer survivors' perception of participation in a long-term follow-up study. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):41–5.

Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, Bjork O, Steineck G, Henter JI. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9162–71.

Omerov P, Steineck G, Dyregrov K, Runeson B, Nyberg U. The ethics of doing nothing. Suicide-bereavement and research: ethical and methodological considerations. Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3409–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713001670.

Rosenberg SM, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, Ruddy KJ, Bober SL, Kereakoglow S, et al. Treatment-related amenorrhea and sexual functioning in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2264–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28738.

Beckjord EB, Arora NK, Bellizzi K, Hamilton AS, Rowland JH. Sexual well-being among survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(5):E351–9. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.E351-E359.

Recklitis CJ, Sanchez Varela V, Ng A, Mauch P, Bober S. Sexual functioning in long-term survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Psychooncology. 2010;19(11):1229–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1679.

Surbeck W, Herbet G, Duffau H. Sexuality after surgery for diffuse low-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17(4):574–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou326.

Giraldi A, Kristensen E. Sexual dysfunction in women with diabetes mellitus. J Sex Res. 2010;47(2):199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224491003632834.

Miaskowski C, Mastick J, Paul SM, Topp K, Smoot B, Abrams G, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;54(2):204–18 e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.342.

Park EM, Rosenstein DL. Depression in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(2):171–80.

Bae H, Park H. Sexual function, depression, and quality of life in patients with cervical cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3):1277–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2918-z.

Hartung TJ, Brahler E, Faller H, Harter M, Hinz A, Johansen C, et al. The risk of being depressed is significantly higher in cancer patients than in the general population: prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms across major cancer types. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.017.

Drost FM, Mols F, Kaal SE, Stevens WB, van der Graaf WT, Prins JB, et al. Psychological impact of lymphoma on adolescents and young adults: not a matter of black or white. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):726–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0518-7.

Blackmore C. The impact of orchidectomy upon the sexuality of the man with testicular cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1988;11(1):33-40.

Geue K, Schmidt R, Sender A, Sauter S, Friedrich M. Sexuality and romantic relationships in young adult cancer survivors: satisfaction and supportive care needs. Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1368–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3805.

Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Arver S, Fredrikson M, Gothberg M, et al. Sexual desire, erection, orgasm and ejaculatory functions and their importance to elderly Swedish men: a population-based study. Age Ageing. 1996;25(4):285–91.

Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8(2):560–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02127.x.

Onat G, Kizilkaya Beji N. Effects of infertility on gender differences in marital relationship and quality of life: a case-control study of Turkish couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(2):243–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.033.

Ramezanzadeh F, Aghssa MM, Jafarabadi M, Zayeri F. Alterations of sexual desire and satisfaction in male partners of infertile couples. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):139–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1285.

Cousineau TM, Domar AD. Psychological impact of infertility. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21(2):293–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.003.

Hall AE, Boyes AW, Bowman J, Walsh RA, James EL, Girgis A. Young adult cancer survivors' psychosocial well-being: a cross-sectional study assessing quality of life, unmet needs, and health behaviors. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(6):1333–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1221-x.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all adolescents and young adults who shared their experiences and views by participating in this study. We also want to thank participating Regional Cancer Centers for their support and help in conducting this study. This study was generously supported by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine and Assar Gabrielsson’s Foundation and Stiftelsen Samariten.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, Sweden, granted ethical approval of this study with the reference number 691-13 and additional reference number 944-14. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Olsson, M., Steineck, G., Enskär, K. et al. Sexual function in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors—a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv 12, 450–459 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0684-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0684-x