Abstract

Background

Previous research on cancer and sexuality has focused on physical aspects of sexual dysfunction, neglecting the subjective meaning and consequences of sexual changes. This has led to calls for research on cancer and sexuality to adopt an “integrative” approach, and to examine the ways in which individuals interpret sexual changes, and the subjective consequences of sexual changes.

Method

This study examined the nature and subjective experience and consequences of changes to sexual well-being after cancer, using a combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis. Six hundred and fifty seven people with cancer (535 women, 122 men), across a range of reproductive and non-reproductive cancer types completed a survey and 44 (23 women, 21 men) took part in an in-depth interview.

Results

Sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction and engagement in a range of penetrative and non-penetrative sexual activities were reported to have reduced after cancer, for both women and men, across reproductive and non-reproductive cancer types. Perceived causes of such changes were physical consequences of cancer treatment, psychological factors, body image concerns and relationship factors. Sex specific difficulties (vaginal dryness and erectile dysfunction) were the most commonly reported explanation for both women and men, followed by tiredness and feeling unattractive for women, and surgery and getting older for men. Psychological and relationship factors were also identified as consequence of changes to sexuality. This included disappointment at loss of sexual intimacy, frustration and anger, sadness, feelings of inadequacy and changes to sense of masculinity of femininity, as well as increased confidence and self-comfort; and relationship strain, relationship ending and difficulties forming a new relationship. Conversely, a number of participants reported increased confidence, re-prioritisation of sex, sexual re-negotiation, as well as a strengthened relationship, after cancer.

Conclusion

The findings of this study confirm the importance of health professionals and support workers acknowledging sexual changes when providing health information and developing supportive interventions, across the whole spectrum of cancer care. Psychological interventions aimed at reducing distress and improving quality of life after cancer should include a component on sexual well-being, and sexual interventions should incorporate components on psychological and relational functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Changes to sexuality after cancer

With cancer survival rates at 5 years currently over 60% [1], increasing numbers of individuals are living with the disease, leading to a focus on the quality of life of survivors, and their families. Sexual well-being is a central component of quality of life [2], and there is a growing body of research demonstrating the association between cancer and changes to sexuality and intimacy, primarily resulting from the impact of cancer treatment [3]. These changes can lead to significant distress, which in some instances can be experienced as the most difficult aspect of life following cancer [4].

Research examining changes to sexuality after cancer has primarily focused on cancers that directly affect the sexual or reproductive body. In men, this has involved examination of sexual changes following prostate and testicular cancer treatment, which include erectile dysfunction [5,6], diminished genital size, weight gain, urinary incontinence [7,8], reductions in sexual desire and enjoyment, as well as negative body image [9-12]. Research on sexual changes for women with cancer has primarily focused on the impact of treatments for gynaecological or breast cancer, which include anatomical changes [13-15], tiredness [16], vaginal pain or dryness [17,18], as well as negative feelings of sexual un-attractiveness [19,20], and changes to sense of femininity [21,22]. This can result in reductions in sexual desire [23], and response [24,25], leading to decreased frequency of sex [26], and lack of sexual pleasure or satisfaction [27,28].

There is growing evidence that individuals with cancers that do not directly affect the sexual or reproductive body can also experience a reduction in sexual interest and sexual activity, changes to body image and feelings of sexual competency, as well as sexual dysfunction, and alterations to sexual self-esteem [29,30]. For example, researchers have reported sexual changes in people with lymphatic [31,32], colon [33], head and neck [34,35], colorectal [36-38], bladder [39], and lung cancers [40]. However, interventions to ameliorate the impact of sexual changes have largely focused on sexual or reproductive cancers [41], and health professionals have been reported to be less likely to discuss sexual changes with individuals or couples experiencing a non-reproductive cancer [42-44]. This suggests that the sexual needs and concerns of those experiencing a wide range of non-reproductive cancers may not be acknowledged or addressed. There is a need for further research examining the nature and subjective experience of changes to sexuality, for both women and men, across a range of cancer types. This is one of the aims of the present study.

Subjective experience and consequences of sexual changes after cancer

Previous research on cancer and sexuality has focused on sexual functioning, or on examination of factors that predict sexual dysfunction, focusing on demographic variables [45-48], type of treatment [36,49,50], or relationship context [51]. Whilst this body of work is important in identifying factors that may be associated with sexual difficulties after cancer, little attention has been paid to the subjective and social meaning and consequences of such sexual changes [37,52]. This has led to calls for research on cancer and sexuality to adopt an “integrative” approach ([53], p.3717), recognising physical, psychological, and relational aspects of experience [37], as well as the ways in which social constructions of sex influence the experience of sexual change [52,54,55]. In this vein, there is a substantial body of research examining the psychological consequences of sexual changes experienced after cancer [6,30,36,37,48,56-58], suggesting that sexual difficulties are associated with lower quality of life, and higher levels of distress. There is also evidence that sexual changes after cancer can impact upon the couple relationship [59], due to emotional distance between couples [60], feeling unwanted by one’s partner [16], negative thoughts about sexual contact [61], or difficulty with couple communication [62,63].

Previous research on psychological and relational aspects of changes to sexuality after cancer has primarily used quantitative methods of data collection. Whilst this provides important information about the nature and psycho-social correlates of sexual changes, it does not enable analysis of the subjective experience and meaning of such changes for people with cancer [64]. There has been some qualitative research that has examined changes to sexuality after cancer see [11,16,21], and the ways in which socio-cultural discourses shape the experience and interpretation of sexuality [52,65]. However, this research has been based on a small number of participants, primarily with sexual or reproductive cancers, which limits insights into the experience of individuals with other types of cancer.

Study aims and research questions

There is a need for a larger mixed method study across a range of relationship contexts and cancer types to examine the nature and subjective experience of changes to sexual well-being after cancer, as well as the perceived individual and relational consequences, using a broad definition of sexual activity. This is the aim of the present study. We are adopting an integrative material-discursive-intrapsychic (MDI) model [64,66], which conceptualises sex and sexual well-being as a multi-faceted construct [67], wherein the effects of cancer and its treatment result from the interconnection of material, discursive and intrapsychic factors. This includes the materiality of embodied sexual changes after cancer, including changes in desire and functioning, and anatomical changes resulting from cancer treatment, as well as the material context of people’s lives, such as whether they are in a relationship or have partner support; changes which occur at an intrapsychic level, such as reductions on psychological well-being, and changes to sexual self-schema [68], identity [69], or body image [61]; and socio-cultural representations and discourses which shape the experience and interpretation of sex, telling us what is ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ sexual behaviour [55]. In contrast to bio-psycho-social models of experience [70], which conceptualise biology, psychology and social factors as independent, the MDI model conceptualises material, intrapsychic and discursive factors as inseparable. For example, the experience of material changes to sexual functioning which result from prostate cancer treatment – erectile dysfunction and reductions in sexual desire - is inseparable from intrapsychic responses to such changes – feelings of loss of manhood and depression [5] – and the discursive context which positions erectile functioning as sign of masculinity, and performance of coital sex as ‘real sex’ [71].

Within this MDI framework, we addressed the following questions: What is the nature and subjective experience of sexual changes experienced after cancer, for women and men, across reproductive and non-reproductive cancers? What are the perceived causes and consequences of such changes, for the person with cancer, and for their intimate relationship?

Method

Participants

Six hundred and fifty seven people with cancer (535 women, 122 men) took part in the study, part of a larger mixed methods project examining the construction and experience of changes to sexuality after cancer [43,51,55,72]. The average age of survey participants was 52.6 years (range 19-87) and cancer was diagnosed on average five years prior to participation in the study (range 1 month – 40 years). The majority (95%) identified as from an Anglo-European-Australian background, with the remainder identifying as from Asian, Aboriginal and Indian subcontinent backgrounds. The following cancer types were reported: breast (64.7%), prostate (13.2%), gynaecological (6.8%), haematological (5.6%), gastrointestinal (2.3%), neurological (1.5%), skin (1.5%), head and neck (0.9%), respiratory (0.2%), and other (0.4%). There were no significant demographic differences between participants with sexual or reproductive cancers (breast, prostate, gynaecological), and non-reproductive cancers. Eighty-six per cent of participants were currently in a relationship, 77% living together, with the average relationship length being 20 years (range 2 months-53 years). Ninety five per cent of participants identified as heterosexual, the remainder self-identifying as gay men (1.9%), lesbian (3%), or as poly-sexual (0.1%). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

We recruited participants nationally through cancer support groups, media stories in local press, advertisements in cancer specific newsletters, hospital clinics, and local cancer organisation websites and telephone helplines. Two individuals, a person with cancer and a partner, nominated by a cancer consumer organisation acted as consultants on the project, commenting on the design, method and interpretation of results. We received ethics approval from the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, and from three Health Authorities, from which participants were drawn.

Measures

Participants completed an online or postal questionnaire examining their experiences of sexuality and intimacy post-cancer, using a combination of closed and open-ended survey items. The survey included standardised measures of sexual and relationship functioning, psychological well-being, and quality of life, reported elsewhere [51], as well as measures of sexual satisfaction, sexual frequency, changes in sexual activities, and perceived causes and consequences of sexual changes, reported in the present paper.

Sexual frequency

Participants were asked to report “how frequently did you engage in sexual activity (e.g. sexual intercourse, masturbation, oral sex)?” before the onset of cancer and currently, on a five point scale: never, rarely (less than once a month), sometimes (more than once a month, less than twice a week), often (more than twice a week) and every day. This item was drawn from the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ-14) [73], a validated instrument which evaluates sexual dysfunction, and modified to include the ‘before the onset’ of cancer ratings.

Cause of changes to sexual frequency

Participants who indicated that sexual frequency had changed, were asked to indicate what factors were perceived to be the cause of such change, using a yes/no response. These factors were: medication, surgery, general pain, loss of feeling, tiredness, sex specific difficulties (vaginal dryness, erectile difficulties), body changes, appearance changes, feeling unattractive, relationship change, psychological problems, stress, getting older, and other (self-nominated).

Change in sexual activities

A single item sexual measure developed as part of the study was used to assess “have your sexual activities changed since the onset of cancer?” using a yes/no response.

Nature of change in sexual activities

Participants were then asked “If yes, please indicate the types of sexual activities you engaged in now, and before the onset of cancer (please tick as many boxes as appropriate): kissing; petting, caressing and stroking; masturbating alone; masturbating with your partner; oral sex; sexual intercourse (vaginal and anal); use of sex toys; other (self-nominated)”.

Sexual satisfaction

A single item developed as part of the study was used to assess sexual satisfaction currently, and before cancer, using a 5 point Likert scale, ranging from could not be better, to could not be worse. The wording of the question was: “Below is a rating scale upon which we would like you to record your personal evaluation of how satisfying your sexual relationship is. The rating is simple. Make your evaluation by placing a tick in the appropriate box in each of the two columns that best describes your relationship as it is “Currently” and how it was “Before the Onset of Cancer””.

Open ended survey items

Participants provided qualitative responses to the following open ended questions: “What do you think are the causes of any changes in the type of sexual activities you engage in since the onset of cancer?”; “how have any changes to your sexuality since the onset of cancer made you feel about yourself and your relationship?”

In-depth interviews

At the completion of the survey, participants indicated whether they would like to be considered to take part in a one-to-one interview, to discuss changes to sexuality in more depth, as well as experiences of communication and information provision about sexuality from health professionals, the letter reported elsewhere [74]. Of the 657 survey respondents, 274 responded positively to the invitation. We purposively selected 44 people with cancer for interview (23 women, 21 men) representing a cross section of cancer types and stages, gender, and sexual orientation. The average age of interviewees was 54.6 years, with 50% experiencing a reproductive cancer (prostate, breast, gynaecological, anal) and 50% a non-reproductive cancer (colorectal, melanoma, lymphoma, leukaemia, kidney, bladder, and brain). Individual semi-structured interviews, lasting on average 60 minutes, were conducted by either a woman or man interviewer, on a face-to-face (7) or telephone basis (72). Participants were given a choice as to the mode of interview (telephone or face to face), and asked if they had a preference about the gender of the interviewer: the majority had no preference for gender, but chose telephone modality. Telephone interviews have previously been recommended for interviews regarding sensitive, potentially embarrassing topics [75], such as cancer and sexuality, and pilot interviews indicated that they were an effective modality to utilise in this study. Prior to the interview, participants were sent an information sheet and consent form to read and sign, as well as a list of the interview topics, including: changes to sexuality and intimacy; and experiences of communication and information provision about sexuality with health professionals. All of the interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis of closed responses

The McNemar Chi-Square test for paired samples was used to test before cancer/after cancer differences within gender and cancer classification groups on ratings of sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction. To allow for dichotomous analysis and facilitate interpretation, ratings of sexual frequency were recoded into ‘never or rarely’ and ‘sometime, often and everyday’, whereas ratings of sexual satisfaction were recoded into ‘highly unsatisfying or unsatisfying’ and ‘adequate, satisfying and highly satisfying’ reflecting the direction and meaning of the original Likert scales. The McNemar Chi-Square test was also used to assess differences in frequency data for changes in sexual activities before and after cancer separately for women and men. The Fisher’s Exact Test (FET) was performed upon the categorical data associated with the perceived causes of changes in sexual frequency. In these analyses, the FET calculates the exact probability of significant differences in the reported assignments of women and men. An alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported for principal outcomes.

Qualitative analysis of open ended responses and interviews

The analysis was conducted using theoretical thematic analysis [76], using an inductive approach, with the development of themes being data driven, rather than based on pre-existing research on sexuality and cancer. In the analysis, our aim was to examine data at a latent level, examining the underlying ideas, constructions and discourses that shape or inform the semantic content of the data, interpreted within a material-discursive-intrapsychic theoretical framework [77]. All of the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the answers to open ended questions collated. One of us read the resulting transcripts in conjunction with the audio recording, to check for errors in transcription. Detailed memo notes and potential analytical insights were also recorded during this process. A subset of the interviews and open ended questions was then independently read and reread by two of us to identify first order codes such as “embodied changes”, “emotional distress”, “relational issues”, “interactions with health professionals”, or “support needed”. The entire data set was then coded using NVivo, a computer package that facilitates organization of coded qualitative data. All of the coded data was then read through independently by two members of the research team. Codes were then grouped into higher order themes; a careful and recursive decision making process, which involved checking for emerging patterns, for variability and consistency, and making judgements about which codes were similar and dissimilar. The thematically coded data was then collated and reorganized through reading and rereading, allowing for a further refinement and review of themes, where a number of themes were collapsed into each other and a thematic map of the data was developed. In this final stage, a number of core themes were developed, which essentially linked many of the themes. These included the impact of sexual changes on self and identity [78], communication with health professionals [74], and renegotiation of sexuality [55], reported elsewhere, as well as perception of causes of sexual changes, emotional consequences of sexual changes, and impact of sexual changes on relationships, the focus of the present paper. Following analysis, the data were organised and presented using a conceptually clustered matrix [79], with exemplar quotes drawn from both the interviews and open ended survey questions provided in tables to illustrate each of the themes. The key to the quotes is: M/W = man or woman; age; gay/lesbian/heterosexual; cancer type.

Results

Subjective experience of changes to sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction and sexual activities after cancer

Sexual frequency

Table 2 presents the data on sexual frequency before and after cancer, for men and women, across both reproductive (breast, gynaecological and prostate) and non-reproductive cancers (all other cancers); age band (below and above age 55); years since diagnosis (less or more than two years); and current relationship duration (less or more than 15 years). There was a significant reduction in sexual frequency for both women (χ2 (1, 530) = 186.92, p < .001) and men (χ2 (1, 122) = 27.23, p < .001), with 11.9% of women and 13.1% of men reporting that sex occurred never or rarely before cancer, compared to 52.5% of women and 41% of men making this report after cancer. This pattern of a reported reduction in frequency occurred across all age, cancer type, years since diagnosis and relationship length categories: ≤55 years of age (χ2 (1, 389) = 130.05, p < .001) and ≥56 years of age (χ2 (1, 260) = 83.16, p < .001); reproductive (χ2 (1, 564) = 209.76, p < .001) and non-reproductive cancers (χ2 (1, 82) = 26.26, p < .01); ≤2 years since diagnosis (χ2 (1, 274) = 83.03, p < .001) and ≥3 years since diagnosis (χ2 (1, 375) = 130.06, p < .001); and ≤15 years in current relationship (χ2 (1, 262) = 69.77, p < .001) and ≥16 years in current relationship (χ2 (1, 366) = 141.74, p < .001).

Participants with a reproductive cancer type were significantly more likely to report that sex occurred never or rarely after cancer (52.4%) compared to 32.5% of those with a non-reproductive cancer (χ2 (1, 648) = 11.42, p < .001), but no differences were found in these reports according age, years since diagnosis and years in current relationship.

Sexual satisfaction

Table 3 identifies the changes in sexual satisfaction after cancer, for women and for men, across reproductive and non-reproductive cancers, age band, years since diagnosis and current relationship duration. Both women (χ2 (1, 506) = 186.49, p < .001) and men (χ2 (1, 117) = 39.93, p < .001) rated their sexual relationship as significantly less satisfying after cancer, with 48.8% of women and 44.4% of men rating their current relationship as unsatisfying, compared to 6.7% of women and 4.3% of men before cancer. This finding was consistent across all age, cancer type, years since diagnosis and relationship length categories: ≤55 years of age (χ2 (1, 370) = 140.34, p < .001) and ≥56 years of age (χ2 (1, 250) = 84.15, p < .001); reproductive (χ2 (1, 541) = 217.36, p < .001) and non-reproductive cancers (χ2 (1, 76) = 10.32, p < .01); ≤2 years since diagnosis (χ2 (1, 262) = 91.46, p < .001) and ≥3 years since diagnosis (χ2 (1, 359) = 133.99, p < .001); and ≤15 years in current relationship (χ2 (1, 250) = 81.92, p < .001) and ≥16 years in current relationship (χ2 (1, 354) = 140.51, p < .001).

No differences were found in the proportion of participants after cancer rating the sexual relationship as unsatisfying according to age, years since diagnosis and years in current relationship, although participants with a reproductive cancer type were significantly more likely to report unsatisfying sexual relationships after cancer (49.9%) compared to 35.9% of those with a non-reproductive cancer (χ2 (1, 621) = 5.36, p = .021).

Sexual activities

Seventy eight per cent of women and 76% of men indicated that their sexual activities had changed after cancer. The nature of changes in sexual activities is illustrated in Figure 1, combining reproductive and non-reproductive cancers.

A significant reduction in kissing (χ2 (1, 503) = 47.76, p < .001, 95% CI [.802,.290]), petting/caressing (χ2 (1, 493) = 100.65, p < .001, 95% CI [.032,.139]), self-masturbation (χ2 (1, 479) = 28.19, p < .001, 95% CI [.238,.536]), partner masturbation (χ2 (1, 479) = 64.61, p < .001, 95% CI [.170,.277]), oral sex (χ2 (1, 483) = 108.22, p < .001, 95% CI [.051,.165]), sexual intercourse (χ2 (1, 497) = 115.35, p < .001, 95% CI [.037,.138]), and sex toys (χ2 (1, 473) = 29.71, p < .001, 95% CI [.150,.442]) was reported by women. For men, a significant reduction in kissing (χ2 (1, 104) = 4.27, p = .039, 95% CI [.045,.926]), petting/caressing (χ2 (1, 106) = 4.76, p = .029, 95% CI [.090,.893]), self-masturbation (χ2 (1, 92) = 4.65, p = .031, 95% CI [.166,.924]), oral sex (χ2 (1, 93) = 7.04, p = .008, 95% CI [.077,.729]), and sexual intercourse (χ2 (1, 98) = 23.08, p < .001, 95% CI [.030,.320]) was reported. Although not statistically significant, the use of sex toys in men was the only sexual activity with a reported increase after cancer.

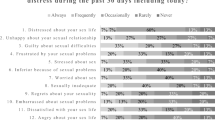

Perceived causes of changes to sexual frequency and activities after cancer

Figure 2 contains responses to the closed ended question asking about perceived causes of reduced frequency of sexual activities, for women and men, combining reproductive and non-reproductive cancers. Sex specific difficulties (vaginal dryness and erectile dysfunction) were the most commonly reported explanation for both women and men, followed by tiredness and feeling unattractive for women, and surgery and getting older for men. Women were significantly more likely than men to indicate that general pain (p = .016; FET), tiredness (p < .001; FET), body changes (p < .001; FET), appearance changes (p < .001; FET), and feeling unattractive (p < .001; FET) were causes of changes to sexual frequency, whereas men were more likely to attribute change to getting older (p = .039; FET).

Four themes were identified in participant’s open ended survey and interview accounts of their perception of what had caused changes in sexual activities following cancer, summarised in Table 4. The most common theme, reported by approximately a third of the total survey sample, related to material changes to the body associated with sexual functioning, such as erectile performance, vaginal dryness or pain, the absence of sexual desire or arousal, or the aging process. A number of participants, approximately one eighth of the survey sample, also reported intrapsychic factors, such as stress, lack of confidence, low self-esteem, or fear, with a similar proportion identifying body image concerns, including feeling ‘hideous’ or ‘grotesque’, or worrying that a partner would find them unattractive. A number of participants, approximately one seventh of the survey sample, also identified relationship context as a factor that exacerbated difficulties, focusing on partner disinterest or rejection.

Perceived consequences of changes to sexual activities after cancer

In response to an open ended survey and interview question asking ‘how have changes to your sexuality made you feel about yourself and your relationship?’, participants described intrapsychic consequences and changes to their intimate relationship.

Intrapsychic consequences of changes to sexuality

Approximately half of the survey participants identified intrapsychic consequences of changes to sexuality. These included disappointment at loss of sexual intimacy, frustration and anger, sadness, feelings of inadequacy and changes to sense of masculinity of femininity, as well as increased confidence and self-comfort, outlined in Table 5.

Relationship changes

A number of participants identified changes to their intimate relationship as a consequence of sexual changes experienced after cancer. These included relationship strain or termination, difficulties forming a new relationship, strengthened relationship, re-prioritisation of sex and re-negotiation of sexual intimacy, illustrated in Table 6.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the subjective experience of changes to sexuality after cancer, as well as the perceived individual and relational causes and consequences of such changes, for women and men, across both reproductive and non-reproductive cancers and a range of relational contexts, using a mixed method design. The findings further develop the findings of previous research, which has primarily focused on either women or men with sexual and reproductive cancers, using quantitative survey methods.

Whilst reported levels of sexual dissatisfaction prior to cancer were comparable with Australian population norms [80], the majority of participants reported significant reductions in sexual satisfaction and frequency, as well as changes in a range of specific sexual activities, after cancer. Whilst a greater proportion of those with prostate, breast or gynaecological reported these sexual changes, the proportion of individuals reporting reductions in sexual frequency and satisfaction after cancer increased significantly for both the reproductive and non-reproductive cancers. This confirms previous research reports of cessation or reduction in sexual frequency after cancer, associated with reductions in sexual satisfaction [3,12,28,64,81], and refutes the notion that such changes are only a concern for individuals with cancer that directly affects the reproductive organs [43]. As there was no effect of time since diagnosis on reports of sexual changes, this confirms previous findings that sexual changes can be experienced at any stage of the cancer journey [16], and can be one of the most enduring negative consequences of cancer [82]. Concerns about sexual changes were also reported across age and gender, refuting the myth that older people are not sexual beings [83,84], and that sexuality is more of a concern to men than to women with cancer [85]. Whilst many older men and women reported distress in relation to sexual changes experienced following cancer, for some participants age was positioned as a cause of such changes, which allowed sexual changes to be positioned as normal or natural, resulting in a reprioritisation of sex within relationships. These findings suggest that broader cultural discourses which position older people as ‘naturally’ less sexual may serve a positive purpose for some individuals, allowing acceptance of sexual change after illness.

Whilst previous research on cancer and sexuality has focused on sexual intercourse [37,54], the present study adopted a broader definition of sex, examining both coital and non-coital sexual practices. Engagement in sexual intercourse was significantly reduced after cancer for both women and men, confirming previous research [13,18,86]. Engagement in non-coital sexual practices, including self and mutual masturbation, oral sex, and kissing, was also reduced, suggesting that once sexual intercourse becomes difficult or impossible, other forms of sexual intimacy may also cease. However, some forms of sexual intimacy did remain, even if reduced. Kissing and petting/caressing were reported to be the most common sexual activities after cancer for both women and men. When viewed in conjunction with a face-value increase in men’s reports of the use of sex toys, and qualitative accounts of the exploration of new sexual practices, or non-genital intimacy, this indicates sexual re-negotiation [87] or flexibility [88] following cancer on the part of some couples. This suggests that future research on sexuality and cancer should not only adopt a wider definition of sex to include non-coital sexual practices, but also examine strategies of sexual re-negotiation [55].

A substantial number of participants in the present study directly attributed changes in sexual frequency and sexual activities to the material consequences of cancer and cancer treatment, including vaginal dryness, erectile dysfunction, tiredness, loss of feeling, and general pain. However, participants also identified intrapsychic factors such as fear, stress, confidence and low self-esteem, as well as concerns about appearance, and relational factors, as causes of sexual changes. At the same time, a range of negative intrapsychic and relational factors were described as consequences of sexual changes experienced after cancer. This confirms previous reports that embodied sexual changes [78], psychological distress [6,45], relationship context [51,89,90], are associated with sexual difficulties after cancer, reinforcing the view that research on sexuality and cancer should adopt an integrative approach that acknowledges biological, psychological and relational factors [36,37,53]. The findings of the present study suggests that psycho-social and relational factors can be conceptualised as both causes and consequences of sexual changes experienced after cancer, which may operate in a vicious cycle of increasing difficulty and distress in the absence of information or support. This is in contrast to previous quantitative research which has examined psycho-social and relational factors as either predictors of sexual dysfunction after cancer e.g. [12,27,36,45], or as outcomes of sexual changes e.g. [56,91,92].

The material-discursive-intrapsychic model adopted in this research also acknowledges the discursive construction of gender and the sexual body in conceptualising the experience of sexual changes after cancer [78,93]. In this vein, many women participants attributed sexual changes after cancer to body image concerns, and to feeling unattractive as a consequence of sexual changes. This supports previous reports that cancer can serve as an ‘invisible assault to femininity’ [94], associated with diminished gender identity [59,95], and feelings of lack of sexual attractiveness and sexual confidence [96,97]. Socio-cultural constructions of idealised femininity normalise sexually attractive women as thin and young [98], with intact breasts signifying desirability [99]. Whilst such ‘emphasised femininity’ [100] is often unattainable, it is a core cultural ideal that shapes many women’s experiences of embodiment [101]. As the present study shows, these constructions impact on women’s sexual practices and subjectivity post-cancer – leading many of the participants feeling that they are now noncompliant with femininity, because they are reportedly ‘inadequate’, ‘fat’, ‘different’, ‘grotesque’ and ‘sexually unattractive’.

At the same time, a number of men also described concerns about masculinity, focusing on feelings of inadequacy, as reported in previous research on identity and sexuality in men with cancer [11,12,102,103]. Loss of erectile function can lead men to feel a change in their self-worth and manhood [7], with men who have prostate cancer reporting that they no longer live up to social expectations of masculine behaviour [104]. Men have also reported that their sexuality is ‘fractured’ post-cancer due to the onset of ‘failed’ sexual performance and diminished desire and pleasure [11]. In addition, men have reported feeling as though they are failing in their intimate relationship post-cancer, with erectile dysfunction seen as limiting the means by which they can ‘meet the needs of their partner’ [105,106]. Similar accounts were evident in the present study, in reports of perceived personal and relationship failure on the part of male participants- see also [93]. These accounts draw on discursive constructions of ‘real sex’ as coital penetration; described as the “coital imperative” [107,108] (pp44), (pp229), these socially constructed meanings serve to “set the horizon of the possible” in terms of sexual desire and behaviour [109], (pp16), provide the context within which individuals construct and experience changes to sexual feelings or behaviour following cancer.

Conversely, we found that a number of participants reported greater sexual confidence, a more positive self-image and increased relational closeness. Many of these participants reported being far less critical of their body post-cancer, less insecure about body image, as well as sexually empowered [78]. The responses of partners were a central part of this positive response, confirming previous research in this area [90,110,111], with many participants providing accounts that partner suggested acceptance of sexual changes, and continuation of partner interest and desire, was a helpful way of negotiating and dealing with the disruption of cancer. The importance of the discursive construction of the post-cancer sexual body was evident in accounts of relational negotiation of sexuality, wherein partners were reported to have positioned the changed sexual body as abject, or conversely, accepted sexual changes. These accounts draw on broader cultural discourse about sexual embodiment and illness, wherein breaches of bodily boundaries through leakage of fluid, surgical scarring, or the use of medical interventions such as a colostomy bag, signify disgust and decay, the anathema of sexual attractiveness or desire [112,113].

This study has a number of strengths and limitations. The strengths were the inclusion of men and women across a range of cancer types, ages, cancer stages and relationship contexts, to examine the subjective experience and consequences of sexual changes after cancer. The mixed method design, and relatively large sample for the qualitative component, is also a strength. Whilst previous research has focused on the heterosexual population, the present study included individuals who identified as gay, lesbian and polysexual, confirming that sexual changes also affect this hitherto “hidden population” [114]. However, as sample size of LGB individuals precluded sub-group analysis, further research is needed to examine the causes and consequences of sexual changes and renegotiation after cancer within a larger population of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals, who have been described as an “overlooked health disparity” ([115], p1009) in the context of cancer. Further limitations were the use of a single item to measure sexual satisfaction, and non-standardised measures of changes to sexual frequency and sexual activities. The retrospective nature of data collection, asking participants to report on perceived changes pre-post cancer, was also a limitation; prospective analysis of sexual changes through the course of diagnosis and treatment would overcome this. The over representation of women with breast cancer, and low representation of men in the sample is also a limitation. Whilst breast cancer is the most common cancer affecting women, there is an under-representation of prostate cancer, the most common cancer affecting men, as well as other common cancer types [1], including respiratory, skin, gastro-intestinal and head and neck cancers. This may be because individuals with non-reproductive cancers are less likely to volunteer for a study on sexual changes, as well as effective strategies of participant recruitment on the part of breast cancer organisations. Future research which specifically targets non-reproductive cancers is needed to examine the subjective experience of sexual changes after cancer, and examine whether the present findings can be generalised.

Clinical implications

The findings of the present study have a number of clinical implications. Firstly, they confirm the importance of health professionals and support workers acknowledging sexual changes when providing health information and developing supportive interventions. There is evidence that information about sexual changes and strategies of re-negotiation is often not forthcoming in clinical consultations [44,116], in particular for women and for individuals with a non-reproductive cancer [43], and as a result patient sexual concerns are unaddressed. Equally, whilst a range of one-to-one and couple interventions have been developed to address sexual difficulties after cancer [41,117-120], these are primarily focused on the functioning of the body for individuals with breast, prostate or gynaecological cancer. There needs to be an expansion of such support into non-reproductive cancers, to address the concerns and support needs of patients and their partners, across cancer stage, age, and relationship status, with the impact of cancer on sexuality acknowledged by researchers and health professionals working across the whole spectrum of cancer care.

Secondly, our findings suggest that psychological interventions aimed at reducing distress and improving quality of life after cancer should include a component on sexual well-being, and conversely, that sexual interventions should incorporate components on psychological and relational functioning. Clinicians need to acknowledge the complex meanings individuals with cancer attribute to sexual changes, in the context of their individual lives and relationships, rather than solely focusing on the functioning of the sexual body [52]. The implication of the finding that partners play a key role in perception of changes to sexuality points to the need for health professionals to recognise the relational and intersubjective nature of sexuality so that discussion of sexuality between people with cancer and their partners is normalised and legitimated [121]. As previous research has reported that couple therapies which facilitate relational coping and communication in the context of cancer are effective in reducing distress e.g. [122-124], couple focused information and supportive interventions to reduce sexual concerns may be beneficial for those in a sexual relationship. However, sexual concerns also affect single people, as was evidenced by accounts of difficulties in forming new relationships in the present study. Information and support services also need to acknowledge and address the specific needs and concerns of single people, a group whose sexual concerns are often overlooked by clinicians [43,125].

Thirdly, our findings suggest that clinicians should adopt a broad conceptualisation of sex when discussing sexual changes, and sexual renegotiation after cancer, rather than focusing on coital sex. There have been previous reports of renegotiation of sexual practices following cancer, with men with prostate cancer reporting “different” and “better” sex after treatment ([126], p323), expressing intimacy through oral sex and touch, rather than penetration [127,128]. Research with partners of people with cancer has also reported renegotiation of sex to include practices previously positioned as secondary to “real sex”, such as mutual masturbation and oral sex [42,110]. This suggests that couples can resist the “coital imperative” ([108], p.229), the biomedical model of sex enshrined in definitions of ‘sexual dysfunction’, which conceptualises sex as penis-vagina intercourse. However, little attention has been given to renegotiation of sexual practice or intimacy after cancer, which has led to a plea for more attention to be paid to “successful strategies used by couples to maintain sexual intimacy” ([129], p142).

Conclusions

Whilst previous research on cancer and sexuality has primarily focused on women with breast or gynaecological cancers, or men with prostate or testicular cancer, the findings of the present study demonstrate that post-cancer sexual and body image issues are also a concern for many women and men with non-reproductive cancers – including those in this sample with haematological, gastrointestinal, neurological, skin, respiratory, and head and neck cancers, across a range of age-groups, cancer stages and relationship contexts. For many individuals, these changes were a source of distress or relationship difficulty. This suggests that acknowledgment of sexuality should be on the agenda of cancer researchers, clinicians and policy makers, in order to facilitate prevention and intervention strategies that aim to reduce distress associated with sexual changes experienced after cancer and assist with sexual renegotiation.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, editor. Cancer in Australia: An Overview 2014. Canberra: AIHW; 2014. Cat. No CAN 88.

World Health Organisation. The world health organisation quality of life assessment (whoqol) position paper. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1403–9.

Mercadante S, Vitrano V, Catania V. Sexual issues in early and late stage cancer: a review. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(6):659–65.

Anderson BL, Golden-Kreutz DM. Sexual self-concept for the women with cancer. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, De-Nour AK, editors. Cancer and the family. London: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. p. 311–6.

Arrington MI. Prostate cancer and the social construction of masculine sexual identity. Int J Mens Health. 2008;7(3):299–306.

Galbraith ME, Arechiga A, Ramirez J, Pedro LW. Prostate cancer survivors’ and partners’ self-reports of health-related quality of life, treatment symptoms, and marital satisfaction 2.5-5.5 years after treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(2):E30–41.

Bokhour BG, Clarke JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:649–55.

Badr H, Carmack Taylor CL. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18(7):735–46.

Carpentier MY, Fortenberry JD. Romantic and sexual relationships, body image, and fertility in adolescent and young adult testicular cancer survivors: a review of the literature. J Adolescent Health. 2010;47(2):115–25.

Tuinman MA, Hoekstra HJ, Vidrine DJ, Gritz ER, Sleijfer DT, Fleer J, et al. Sexual function, depressive symptoms and marital status in nonseminoma testicular cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncol. 2010;19(3):238–47.

Gurevich M, Bishop S, Bower J, Malka M, Nyhof-Young J. (Dis)embodying gender and sexuality in testicular cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(9):1597–607.

Rossen P, Pedersen AF, Zachariae R, von der Maase H. Sexuality and body image in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(4):571–8.

Basson R. Sexual function of women with chronic illness and cancer. Womens Health. 2010;6(3):407–29.

Schover LR, Fife M, Gershenson DM. Sexual dysfunction and treatment for early stage cervical cancer. Cancer. 1989;63(1):204–12.

Holmes L. Sexuality in gynaecological cancer patients. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2005;4(6):35–9.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Changes to sexual well-being and intimacy after breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(6):456–64.

Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. New Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1383–9.

Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Quality of life and sexual functioning in young women with early-stage breast cancer 1 year after lumpectomy. Psycho-Oncol. 2013;22(6):1242–8.

Bertero C, Wilmoth MC. Breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment affecting the self. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(3):194–202.

Plotti F, Sansone M, Di Donato V, Antonelli E, Altavilla T, Angioli R, et al. Quality of life and sexual function after type C2/type III radical hysterectomy for locally advanced cervical cancer: a prospective study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(3):894–904.

Archibald S, Lemieux S, Byers ES, Tamlyn K, Worth J. Chemically-induced menopause and the sexual functioning of breast cancer survivors. Women Ther. 2006;29(1/2):83–106.

Wilmoth MC. The aftermath of breast cancer: an altered sexual self. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24(4):278–86.

Sekse RJT, Raaheim M, Blaaka G, Gjengedal E. Life beyond cancer: women’s experiences 5 years after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(4):799–807.

Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D’Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2006;15(7):579–94.

Bal MD, Yilmaz SD, Beji NK. Sexual health in patients with gynecological cancer: a qualitative study. Sex Disabil. 2013;31(1):83–92.

Green M, Naumann RW, Elliott M, Hall J, Higgins R, Grigsby JH. Sexual dysfunction following vulvectomy. In: Gynecologic Oncology. vol. 77th ed. 2000. p. 73–7.

Juraskova I, Butow P, Bonner C, Robertson R, Sharpe L. Sexual adjustment following early stage cervical and endometrial cancer: prospective controlled multi-centre study. Psycho-Oncol. 2013;22(1):153–9.

Meyerowitz B, Desmond K, Rowland J, Wyatt G, Ganz P. Sexuality following breast cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 1999;25:237–50.

Galbraith ME, Crighton F. Alterations of sexual function in Men with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(2):102–14.

Greenfield DM, Walters SJ, Coleman RE, Hancock BW, Snowden JA, Shalet SM, et al. Quality of life, self-esteem, fatigue, and sexual function in young Men after cancer: a controlled cross-sectional study. Cancer. 2010;116(6):1592–601.

Jonker-Pool G, Hoekstra HJ, van Imhoff GW, Sonneveld DJA, Sleijfer DT, van Driel MF, et al. Male sexuality after cancer treatment-needs for information and support: testicular cancer compared to malignant lymphoma. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(2):143–50.

Jarden M, Schjodt I, Thygesen KH. The impact of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on sexuality: a systematic review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:716+.

van der Horst-Schrivers ANA, van Ieperen E, Wymenga A, Boezen H, Weijmar-Schultz WCM, Kema IP, et al. Sexual function in patients with metastatic midgut carcinoid tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89(2):231–6.

Low C, Fullarton M, Parkinson E, O’Brien K, Jackson SR, Lowe D, et al. Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(10):898–903.

Monga U, Tan G, Ostermann HJ, Monga TN. Sexuality in head and neck cancer patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(3):298–304.

Milbury K, Cohen L, Jenkins R, Skibber JM, Schover LR. The association between psychosocial and medical factors with long-term sexual dysfunction after treatment for colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3)):793–802.

Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Den Oudsten BL. Sexual (dys)function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(1):19–27.

Donovan KA, Thompson LM, Hoffe SM. Sexual function in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2010;17(1):44–51.

Salem HK. Radical cystectomy with preservation of sexual function and fertility in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: New technique. Int J Urol. 2007;14:294–8.

Shell JA, Carolan M, Zhang Y, Meneses KD. The longitudinal effects of cancer treatment on sexuality in individuals with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(1):73–9.

Miles C, Candy B, Jones L, Williams R, Tookman A, King M. Interventions for sexual dysfunction following treatments for cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:1–61.

Hawkins Y, Ussher JM, Gilbert E, Perz J, Sandoval M, Sundquist K. Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis of cancer. The experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2009;34(4):271–80.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WKT, Mason C, Hobbs K, et al. Talking about sex after cancer: a discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol Health. 2013;28(12):1370–90.

Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186(5):224–7.

Kiserud CE, Schover LR, Dahl AA, Fosså A, Bjøro T, Loge JH, et al. Do male lymphoma survivors have impaired sexual function? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):6019–26.

Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, Leonard M. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2010;19(8):814–22.

Jenkins R, Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke C, Neese L, Klein EA, et al. Sexuality and health-related quality of life after prostate cancer in African-American and white Men treated for localized disease. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30(2):79–93.

Den Oudsten BL, Van Heck GL, Van der Steeg AFW, Roukema JA, De Vries J. Clinical factors are not the best predictors of quality of sexual life and sexual functioning in women with early stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2010;19:646–56.

Greimel ERWRKSHJ. Quality of life and sexual functioning after cervical cancer treatment: a long-term follow-up study. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18(5):476–82.

Biglia N, Moggio G, Peano E, Sgandurra P, Ponzone R, Nappi RE, et al. Effects of surgical and adjuvant therapies for breast cancer on sexuality, cognitive functions, and body weight. J Sex Med. 2010;7(5):1891–900.

Perz J, Ussher JM, Gilbert E. Feeling well and talking about sex: psycho-social predictors of sexual functioning after cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):228–47.

White ID, Faithfull S, Allan H. The re-construction of women’s sexual lives after pelvic radiotherapy: A critique of social constructionist and biomedical perspectives on the study of female sexuality after cancer treatment. Soc Sci Med. 2013;76:188–96.

Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. JCO. 2012;30(30):3712–9.

Hyde A. The politics of heterosexuality—a missing discourse in cancer nursing literature on sexuality: A discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(2):315–25.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WKT, Hobbs K. Renegotiating sex after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(6):454–62.

Dahn JR, Penedo FJ, Gonzalez JS, Esquiabro M, Antoni MH, Roos BA, et al. Sexual functioning and quality of life after prostate cancer treatment: considering sexual desire. Urology. 2004;63(2):273–7.

Matthews AK, Aikens JE, Helmrich SP, Anderson DD, Herbst AL, Waggoner SE. Sexual functioning and mood among long-term survivors of clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina or cervix. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2000;17(3-4):27–45.

Andersen BL. Surviving cancer. Cancer. 1994;74(4):1484–95.

Burns M, Costello J, Ryan-Woolley B, Davidson S. Assessing the impact of late treatment effects in cervical cancer: an exploratory study of women’s sexuality. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16(4):364–72.

Rolland JS. In sickness and in health: The impact of illness on couples’ relationships. J Marital Fam Ther. 1994;20(4):327–35.

Cull A, Cowie VJ, Farquharson DIM, Livingstone JRB, Smart GE, Elton RA. Early stage cervical cancer: psychosocial and sexual outcomes of treatment. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:1216–20.

Bourgeois-Law G, Lotocki R. Sexuality and gynaecological cancer: a needs assessment. Can J Hum Sex. 1999;8(4):231–40.

Stead ML, Fallowfield L, Selby P, Brown JM. Psychosexual function and impact of gynaecological cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21(2):309–20.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Sexuality after breast cancer: a review. Maturitas. 2010;66:397–407.

Young IM. Breasted experience: the look and the feeling. In: Leder D, editor. The body in medical thought and practice. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. p. 215–32.

Ussher JM. Women’s Madness: A Material-Discursive-Intra psychic Approach. In: Fee D, editor. Psychology and the Postmodern: Mental Illness as Discourse and Experience. London: Sage; 2000. p. 207–30.

Cleary V, Hegarty J. Understanding sexuality in women with gynaecological cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(1):38–45.

Andersen BL, Woods XE, Copeland LJ. Sexual self-schema and sexual morbidity among gynaecologic cancer survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;65(2):221–9.

Charmaz C. The body, identity, and self: adapting to impairment. Sociol Q. 1995;36(4):657–80.

Engel G. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for bio-medicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36.

Potts A. The essence of the hard on”. Men and Masc. 2000;3(1):85–103.

Perz J, Ussher JM, Gilbert E. Constructions of sex and intimacy after cancer: Q methodology study of people with cancer, their partners, and health professionals. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:270.

Keller A, McGarvey EL, Clayton AH. Reliability and construct validity of the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire short-form (CSFQ-14). J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(1):43–52.

Gilbert E, Perz J, Ussher JM: Talking about Sex with Health Professionals: The Experience of People with Cancer and their Partners. Eur J Cancer Care 2014, in press.

Sturges J, Hanrahan K. Comparing Telephone and Face-to-Face Qualitative Interviewing: A Research Note. Qual Res. 2004;4:107–18.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Ussher JM. Unravelling women’s madness: Beyond positivism and constructivism and towards a material-discursive-intrapsychic approach. In: Menzies R, Chunn DE, Chan W, editors. Women, madness and the law: A feminist reader. London: Glasshouse press; 2005. p. 19–40.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Embodying sexual subjectivity after cancer: A qualitative study of people with cancer and intimate partners. Psychol Health. 2013;28(6):603–19.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc; 1994.

Badcock PB, Smith AMA, Richters J, Rissel C, de Visser RO, Simpson JM, et al. Characteristics of heterosexual regular relationships among a representative sample of adults: the Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sex Health. 2014;11(5):427–38.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Sexuality after gynaecological cancer: A review of the material, intrapsychic, and discursive aspects of treatment on women’s sexual-wellbeing. Maturitas. 2011;70(1):42–57.

De Groot JM, Mah K, Fyles A, Winton S, Greenwood S, De Petrillo AD, et al. The psychosocial impact of cervical cancer among affected women and their partners. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:918–25.

Loe M. Sex and the senior woman: pleasure and danger in the Viagra Era. Sexualities. 2004;7(3):303–26.

Watters Y, Boyd TV. Sexuality in later life: opportunity for reflections for healthcare providers. Sex Rel Ther. 2009;24(3-4):307–15.

Traa MJ, Orsini RG, Oudsten BLD, Vries JD, Roukema JA, Bosman SJ, et al. Measuring the health-related quality of life and sexual functioning of patients with rectal cancer: Does type of treatment matter? Int J Cancer. 2013;134(3):979–87.

Jankowska M. Sexual functioning of testicular cancer survivors and their partners – A review of literature. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2012;17(1):54–62.

Ussher JM, Perz J. PMS as a process of negotiation: Women’s experience and management of premenstrual distress. Psychol Health. 2013;28(8):909–27.

Barsky JMR. Sexual dysfunction and chronic illness: the role of flexibility in coping. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(3):235–53.

Alder J, Zanetti R, Wight E, Urech C, Fink N, Bitzer J. Sexual dysfunction after premenopausal stage I and II breast cancer: Do androgens play a role? J Sex Med. 2008;5:1898–906.

Sawin EM. “The Body Gives Way, Things Happen”: Older women describe breast cancer with a non-supportive intimate partner. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(1):64–70.

Howlett K, Koetters T, Edrington J, West C, Paul S, Lee K, et al. Changes in sexual function on mood and quality of life in patients undergoing radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):E58–66.

Hannah MT, Gritz ER, Wellisch DK, Fobair P, Hoppe RT, Bloom JR, et al. Changes in marital and sexual functioning in long-term survivors and their spouses: Testicular cancer versus hodgkin’s disease. Psycho-Oncol. 1992;1(2):89–103.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J, Wong WKT, Hobbs K, Mason C. Men’s experiences of sexuality after cancer: a material discursive intra-psychic approach. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(8):881–95.

Butler L, Banfield V, Sveinson T, Allen K, Downe-Wanboldt B, Alteneder RR. Conceptualizing sexual health in cancer care. West J Nurs Res. 1998;20(6):683–705.

Lamb MA, Sheldon TA. The sexual adaptation of women treated for endometrial cancer. Cancer Pract. 1994;2(2):103–13.

Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, Sharpe L, McLeod C, Hacker N. Post-treatment sexual adjustment following cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight. Psycho-Oncol. 2003;12(3):267–79.

Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Early-stage cervical carcinoma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. Cancer. 2004;100(1):97–106.

Ussher JM. Fantasies of Femininity: Reframing the Boundaries of Sex. London/New York: Penguin/Rutgers; 1997.

Spence J. Cultural sniping: The art of transgression. London: Sage; 1995.

Connell RW. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. California: Stanford University Press; 1987.

Bordo S. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Culture and the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993.

Burns SM, Mahalik JR. Understanding How masculine gender scripts may contribute to Men’s adjustment following treatment for prostate cancer. Am J Mens Health. 2007;1(4):250–61.

Walsh E, Hegarty J. Men’s experiences of radical prostatectomy as treatment for prostate cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:125–33.

Cushman MA, Phillips JL, Wasserug RJ. The language of emasculation: implications for cancer patients. Int J Mens Health. 2010;9(1):3–25.

Maliski SL, Rivera S, Connor S, Lopez G, Litwin MS. Renegotiating masculine identity after prostate cancer treatment. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(12):1609–20.

Fergus KD, Gray RE, Fitch MI. Sexual dysfunction and the preservation of manhood: Experiences of men with prostate cancer. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(3):303–16.

Jackson M. Sex research and the construction of sexuality: A tool of male supremacy? Wom Stud Int Forum. 1984;7(1):43–51.

McPhillips K, Braun V, Gavey N. Defining (hetero)sex: How imperative is the coital imperative? Wom Stud Int Forum. 2001;24:229–40.

Weeks J. Sexuality. London: Routledge; 2003.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: The experiences of carers. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(4):998–1009.

Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: A phone survey of men’s and women’s perspectives. Psycho-Oncol. 2003;12(5):463–73.

Manderson L. Boundary breaches: the body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(2):405–15.

Isaksen LW. Toward a sociology of (gendered) disgust: images of bodily decay and the social organization of care work. J Fam Issues. 2002;23(7):791–811.

Filiault SM, Drummond MJN, Smith JA. Gay men and prostate cancer: voicing the concerns of a hidden population. J Mens health. 2008;5(4):327–32.

Brown JP, Tracy JK. Lesbians and cancer: An overlooked health disparity. Cancer Cause Control. 2008;19(10):1009–20.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Information needs associated with changes to sexual well-being after breast cancer. Eur J Canc Care. 2013;69(3):327–37.

Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, Neese L, Klein EA, Zippe C, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(8):1773–85.

Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2689–700.

Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE. Randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(10):1620–6.

Latini DM, Hart SL, Coon DW, Knight SJ. Sexual rehabilitation after localized prostate cancer: current interventions and future directions. Cancer J. 2009;15:34–40.

Stilos K, Doyle C, Daines P. Addressing the sexual health needs of patients with gynecologic cancers. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):457–63.

Kayser K. Enhancing dyadic coping during a time of crisis: A theory-based intervention with breast cancer patients and their partners. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with chronic illness: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. p. 175–94.

Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1122–35.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Hawkins Y, Brack M. Evaluating the efficacy of psycho-social interventions for informal carers of cancer patients: A systematic review of the research literature. Health Psychol Rev. 2009;3(1):85–107.

Hordern AJ, Street AF. Constructions of sexuality and intimacy after cancer: Patient and health professional perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(8):1704–18.

Potts A, Grace VM, Vares T, Gavey N. ‘Sex for life’? Men’s counter-stories on ‘erectile dysfunction’, male sexuality and ageing. Sociol Health Illn. 2006;28(3):306–29.

Oliffe J. Constructions of masculinity following prostatectomy-induced impotence. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2249–59.

Arrington MI. “I don’t want to be an artificial man”: Narrative reconstruction of sexuality among prostate cancer survivors. Sex Cult. 2003;7(2):30–58.

Beck AM, Robinson JW, Carlson LE. Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. Urol Oncol-Semin Ori. 2009;27(2):137–43.

Acknowledgements

An Australian Research Council Linkage Grant, LP0883344, funded this research in conjunction with the Cancer Council New South Wales and the National Breast Cancer Foundation. We received in-kind support from Westmead Hospital and Nepean Hospital. The chief investigators on the project were Jane Ussher, Janette Perz and Emilee Gilbert and the partner investigators were Gerard Wain, Gill Batt, Kendra Sundquist, Kim Hobbs, Catherine Mason, Laura Kirsten and Sue Carrick. We thank Tim Wong, Caroline Joyce, Emma Hurst, Jennifer Read, Anneke Wray, Jan Marie and Chloe Parton for research support and assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JP, JMU and EG designed, planned and coordinated the study with significant input from The Australian Cancer and Sexuality Study Team (ACSST)1. JP performed the statistical analysis and initial interpretation of the results with JU assisting in the interpretation of data. JMU performed the qualitative analysis, in consultation with JP and EG. JU drafted the manuscript with JP and EG revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

1ACSST members include: Gerard Wain (Westmead Hospital), Gill Batt (Cancer Council New South Wales), Kendra Sundquist (Cancer Council New South Wales), Kim Hobbs (Westmead Hospital), Catherine Mason (Nepean Hospital), Laura Kirsten (Nepean Hospital) Sue Carrick (National Breast Cancer Foundation) and Tim Wong (University of Western Sydney).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ussher, J.M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E. et al. Perceived causes and consequences of sexual changes after cancer for women and men: a mixed method study. BMC Cancer 15, 268 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1243-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1243-8