Abstract

Background

The course of fatigue in long-term breast cancer survivors (BCSs) is unknown. The current study examined chronic fatigue (CF) cross-sectionally and longitudinally in relapse-free women up to 10 years after multimodal treatment for BC stage II/III. The prevalence of persistent fatigue (PF: having CF at two assessments separated by >2 years) and its predictors were also investigated.

Methods

Data from questionnaires (including the Fatigue Questionnaire and questions regarding socio-demographics and physical symptoms) were collected twice from 249 BCSs: 2.5–7 years post-BC diagnosis (T1) and 2.5–3 years thereafter (T2). A physical examination including blood sampling was performed at T1.

Results

CF was diagnosed in 33% of the women at T1 and in 39% at T2, including 57 (23%) subjects with PF. Current psychological distress, treatment-area related discomfort and high body mass index (BMI) were associated with CF at T1 and predicted PF. Increased leukocyte count also predicted PF. Treatment for mental problems prior to the BC, increased hsCRP-level and respiratory symptoms were associated with CF at T1 but did not predict PF.

Conclusions

Women may experience fatigue up to 10 years after multimodal BC treatment, with about one third having CF and about one fourth having PF.

Implications for cancer survivors

During follow-up, BCSs and their doctors should maximize their efforts to reduce psychological distress, overweight and pain within the BC-treated area, all linked to the development of persistent fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fatigue is a subjective experience involving feelings of “tiredness, weakness and/or lack of energy [1] and may also imply a subjective sense of cognitive limitations [2, 3]. Fatigue associated with cancer is “disproportionate to exercise level and not relieved by rest” [4, 5] and has a negative impact on the quality of life of affected individuals [1, 4, 6–9].

Fatigue is a major complaint in breast cancer survivors (BCSs) affecting as many as 30% [1, 10–12]. Most of the previous studies on fatigue in BCSs have been cross-sectional assessing the level of fatigue, but not its duration [5]. Thus, individuals with transient fatigue could not be separated from those with persisting symptoms. Chronic fatigue (CF), defined as fatigue above a certain level for 6 months or longer [13, 14], thus becomes of special relevance in cancer survivors. Further, few studies have explored fatigue in women more than 5 years post-BC treatment [12], and only one of these long-term studies had a longitudinal design [11]. Therefore, knowledge about the course of fatigue in long-term BCSs is limited.

The one long-term longitudinal study demonstrated that depression, high blood pressure, BC-treatment including chemo- and radiotherapy and baseline fatigue scores predicted fatigue [11]. Also a short-term longitudinal study showed that pre-treatment fatigue score predicted fatigue in BCSs at follow-up 2.5 years after treatment [15]. In both cross-sectional and short-term longitudinal studies psychological distress [1, 6, 15, 16] and possible side-effects of BC treatment [1, 6, 7, 16–18] are consistently reported as related to fatigue, while results are conflicting regarding the association between post-treatment fatigue and socio-demographic variables [1, 6], age at BC diagnosis, and disease- and treatment-related factors [1, 6, 10, 15, 18–20]. Some studies indicate that pro-inflammatory cytokines may play a role in the development of fatigue [21, 22], and a prolonged immune response in fatigued BCSs has been proposed [10, 23]. However, factors related to fatigue in short-term longitudinal and cross-sectional studies may not necessarily be associated with persistence of fatigue.

Thus, the aims of the present study were to investigate:

-

1)

The course of CF in long-term BCSs assessed at two separate time points, 2.5–7 years post-BC treatment (T1) and 2.5–3 years after T1 (T2).

-

2)

The prevalence of persistent fatigue (PF i.e. having CF at both T1 and T2).

-

3)

Which clinical factors predict PF?

We hypothesized that young age at BC diagnosis, psychological distress and post-BC-related late effects were associated with PF.

Methods

Study sample

Prior to 2002 most cancer patients living in the southern part of Norway (comprising about 40% of the Norwegian population) were referred to the Norwegian Radium Hospital (NRH) when they needed radiotherapy. In 2004/2005 (T1) women treated for BC stage II/III during the years 1998–2002 with postoperative loco-regional radiotherapy at the NRH were invited to attend a follow-up study on late clinical and biochemical effects. Candidates for study inclusion were identified from the hospital’s radiotherapy registry and had to fulfil the following inclusion criteria: 1) age ≤75 years in 2004/2005, 2) no recurrence of BC, 3) no other cancer except for basal cell carcinoma, carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix, or prior or simultaneous surgery for contra lateral BC stage I with no adjuvant treatment.

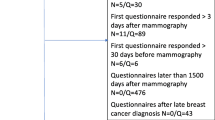

Of the 415 invited eligible women, 317 (76%) women completed the questionnaires and also attended an outpatient physical examination with blood sampling at the NRH at T1.

In 2007, 310 women (registered alive) of those attending the outpatient examination were invited by mail to participate in a second follow-up (T2) by responding to the same questionnaire package as at T1. At T2, 249 (80%) eligible women returned the questionnaires (Fig. 1). Women who had completed the questionnaires both at T1 and at T2 (N = 249) were included in the present study.

Treatment modalities

The women received standardized treatment according to national guidelines issued by the Norwegian Breast Cancer Group. Surgical treatment consisted of modified radical mastectomy (N = 184, 74%) or breast conserving surgery (N = 65, 26%) with axillary dissection at level I–II. Most of the women received adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 199, 80%) and/or anti-estrogen treatment (N = 217, 87%) (Table 1). The radiation target volume included the breast after breast conserving surgery or the chest wall after modified radical mastectomy, the ipsilateral supra- and infraclavicular fossa, lymph nodes along the ipsilateral internal mammary artery and the ipsilateral axilla. Prior to 2000, radiotherapy was based on standardized field arrangements, while from 2000 and onwards, treatment was based on transverse CT-images using a commercial treatment planning system. Radiotherapy with standardized field arrangements was given to 87 (35%) of the BCSs and the CT-based radiotherapy to 162 (65%). Further details regarding patient selection and treatment have been described previously [24].

Due to the unselective recruitment of patients to the hospital and the standardized treatment they received, we consider the sample as representative for Norwegian women treated for BC stage II/III during the relevant period.

Measurements

Patient-reported assessments

Information on socio-demographics, fatigue and mental health was obtained by questionnaires. Marital status was dichotomized as paired (married/cohabiting) versus non-paired (separated/divorced/widows). Level of education was categorized as ≤10 years, 11–12 years or ≥13 years of basic education. “Previous treatment for mental problems” included consultations with a psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist before the survey. A diagnosis of hypothyroidism and use of thyroxin were also recorded.

The fatigue questionnaire (FQ) inquires about fatigue symptoms during the previous month compared to when the subject last felt well [13]. It measures two underlying constructs: 7 items assessing physical fatigue and 4 items measuring mental fatigue (i.e. subjectively reported cognitive difficulties) [13]. Each item has four response alternatives (0–3), with higher scores implying more fatigue. Total fatigue is defined as the sum score of all 11 items, with 33 as the maximum score.

Chalder et al suggested a cut-off point of 4 or higher on a dichotomized scale for case definition [13] and in line with this the raw FQ scores were dichotomized (0 = 0 or 1, 1 = 2 or 3). The FQ has an additional item assessing the duration of the fatigue symptoms, and chronic fatigue (CF) was defined as a sum of dichotomized scores ≥4 combined with symptom duration of 6 months or longer [13, 14].

A recent review of instruments for assessment of cancer-related fatigue recommended use of the FQ [25]. The FQ has been used in numerous studies involving cancer patients [26] with internal consistencies ≥0.85 and a stable factor structure supporting its construct validity [13, 25]. The FQ’s Cronbach’s α’s in the present sample were 0.92 (physical fatigue), 0.87 (mental fatigue) and 0.93 (total fatigue).

In line with prior research [22] subjects having CF at both assessment points were defined as having persistent fatigue (PF).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [27] includes two subscales: anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). Each subscale consists of seven items. Each item has four response alternatives (0 = “not present”, 3 = “severe”), giving sum scores on each subscale from 0 to 21. In line with the author’s recommendations, a sum score ≥8 within either scale was defined as a possible case [27]. Scores above this threshold on one or both subscales were combined into one variable, HADS caseness, classifying subjects with high levels of psychological distress. Cronbach’s α’s in the current study were 0.85 (HADS-A) and 0.83 (HADS-D).

Missing responses in the FQ (2 subjects) and HADS (2 subjects) were replaced by an individualized mean score calculated from the completed items for each scale, given that at least half of the items within that scale had been responded to.

Disease-related data and data from clinical examination

Clinical data were collected from the women’s medical records at the NRH.

At the first assessment, an experienced oncologist scored the presence of tissue fibrosis in the irradiated regions as “none”, “little”, “some” and “substantial”, based upon the LENT SOMA scoring system [28]. The women were asked about pain within or close to the BC-treated area (0 = “none”, 1 = “little”, 2 = “some”, 3 = “substantial” pain). The scores for fibrosis and pain were dichotomized (0 = “none/little”, 1 = “some/substantial”). As both the presence of fibrosis and/or pain contribute to discomfort in the BC-treated area, these factors were merged into one variable; “treatment-area related discomfort” categorized as 0 = “none/little pain and fibrosis” and 1 = “some/substantial pain and/or some/substantial fibrosis”.

The women were also asked whether they experienced respiratory symptoms (“no”/“yes”). Objective respiratory tests included peak expiratory flow and forced expiratory volume.

Body mass index (BMI) at T1 was calculated using the formula BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2 and categorized according to guidelines [29]: underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9) and obese (≥30). Data on weight before chemotherapy and at T1 enabled the assessment of weight changes over time.

Blood tests

Non-fasting blood samples were drawn at T1. Thyroid blood tests (TSH-measurements) were analyzed as described elsewhere [24]. Results on TSH were dichotomized as ≤/>3.5 mU/L [24]. Leukocyte counts and determination of hemoglobin were performed with CELL-DYN® 4000 (Abbott diagnostic division, U.S.A). The reference range for leukocyte count was 3.3–11.0·109 /l and for hemoglobin 11.5–15.5 g/dl. Serum levels of C-reactive protein were measured with a high-sensitivity, particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay (hsCRP), (Roche Diagnostica, Basel, Switzerland). The detection limit for hsCRP was 0.5 μg/l.

Statistics

Continuous variables were described using median and (range), categorical variables with proportions and [95% confidence intervals]. Unadjusted associations were assessed using Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon and Chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Correlations between pairs of continuous variables were measured with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Confidence intervals for proportions of those with incidental and resolving CF at T1 and T2 were constructed using the normal distribution approximation.

Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to identify adjusted associations between different independent variables and PF. Leukocyte count, hemoglobin- and hsCRP-level were treated as continuous variables in the logistic regression models as we assumed linearity on the log-odds scale. Predictors with a p-value <0.1 in the univariate analyses were entered into a multiple logistic regression model. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL).

Ethics

The Regional Committee for Medical and Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate approved the study. All participants gave written informed consent.

Results

Attrition analysis

The 98 women at T1 not attending the outpatient examination did not differ significantly from the responders regarding age at BC diagnosis, BC laterality and type of surgery or radiotherapy. However, a significantly lower proportion of the non-responders had been treated with chemotherapy compared to the responders (69% vs 81%, p = 0.01).

The 68 subjects attending only once did not differ significantly from the 249 included women regarding age at BC diagnosis, follow up time, BC laterality or BC treatment. Neither were there any significant differences between these non-responders and the study population regarding CF status and HADS caseness at T1.

Chronic fatigue at T1

CF was diagnosed in 33% [27–39]% (N = 82), of the 249 women at T1.

Compared to the non-fatigued individuals, a significantly higher proportion of those with CF reported previous treatment for mental problems (4% [1–7]% vs 20% [11–28]%) and were possible HADS cases (17% [11–22]% vs 43% [32–53]%), (p < 0.001, respectively), (Table 1). Further, women with CF experienced significantly more treatment-area related discomfort (p < 0.001) and respiratory symptoms (p = 0.004).

While 30% [21–41]% (N = 25), of the women with CF had BMI ≥ 30 at T1, only 15% [10–20]% (N = 25), of the non-fatigued women were categorized as obese (p = 0.01). Median weight gain was 4.0 kg (−17 to 30)kg in women with CF compared to 2.0 kg (−16 to19)kg in the non-fatigued subjects (p = 0.01).

The levels of hsCRP were significantly higher in subjects with CF as compared to those without CF (median and range: 2.5 (0.2–23.0)mg/l vs 1.5 (0.2–31.0)mg/l [p = 0.004]). A higher hsCRP-level was also significantly associated with treatment-area related discomfort (p < 0.001).

Except for the findings on hsCRP, no significant difference was found between women with or without CF concerning the remaining of the biochemical tests described in the measurements section. Nor did we find any difference between subjects with or without CF regarding age at BC diagnosis or at survey, marital and educational status, different types of cancer treatment or a diagnosis of hypothyroidism.

Even though self-reported respiratory symptoms were significantly associated with CF, the objective respiratory tests were not.

Previous treatment for mental problems, HADS caseness, treatment-area related discomfort and having respiratory symptoms remained significantly associated with CF in a multiple model including all variables significantly related to CF in Table 1.

Course of CF and factors associated with PF

Ninety-seven (39% [33–45]%) of the women had CF at T2, including 57 individuals who also had CF at T1. The latter women were classified as having PF. Twenty-five (10% [6–14]%) women were diagnosed with resolving fatigue- i.e CF only at T1, while 40 (16% [12–21]%) subjects were incident cases with CF only at T2. At both assessment points women with PF had significantly higher total fatigue scores than those with chronic fatigue at either T1 or T2 (p = 0.012 at T1 and p = 0.023 at T2) (Fig. 2). As expected, the total fatigue scores at the two assessment points were significantly correlated (Pearson correlation r = 0.64, p = 0.01).

In the univariate analyses previous treatment for mental problems, HADS caseness, BMI ≥ 30, treatment-area related discomfort, increasing hsCRP and leukocyte count evaluated at T1 were significant predictors for PF, while educational and marital status reached borderline significance (Table 2). Contrary to the findings on CF, respiratory symptoms were not associated with PF. Neither were hemoglobin-level, an elevated TSH or a diagnosis of hypothyroidism related to PF.

hsCRP-level was significantly associated with PF in the univariate analysis and also strongly correlated with treatment-area related discomfort. In the multiple analysis, treatment-area related discomfort remained a significant predictor while hsCRP did not reach significance.

In the final multiple model BMI ≥ 30, treatment-area related discomfort, HADS caseness, increasing leukocyte count and 11–12 years of education remained significant predictors for PF. Previous treatment for mental problems reached borderline significance (p = 0.06).

Discussion

In the current study 23% of the attending women had PF, i.e. they were diagnosed with CF at 2.5–7 years after their BC treatment (T1) and then again 2.5–3 years later (T2). CF was diagnosed in 33% of the attending women at T1 and in 39% at T2. However, these proportions do not always refer to the same individuals. While 10% had resolving fatigue with CF only at T1, 16% were incident cases with CF only at T2. Thus, our data demonstrate that CF after BC treatment is not necessarily a constant condition.

Current psychological distress, treatment-area related discomfort and BMI ≥ 30 were associated with CF at T1 and were also significant predictors for PF in the multiple analyses. In our sample an increased leukocyte count (still within the reference range) was also associated with PF. While respiratory symptoms and a higher hsCRP-level were related to CF in the cross-sectional study at T1, these factors did not significantly predict PF in the multiple model. Further, individuals with PF had significantly higher total fatigue scores at both assessments compared to the scores of subjects with CF only at either time point.

Our finding that about one third of the women had CF at each assessment point is in line with previously published results [1, 11]. Regarding the persistence of fatigue, one study reported that 19% of relapse-free women were severely fatigued both 29 months post-BC treatment and 2 years thereafter [30], while another reported that 21% of the BCSs surveyed 5–10 years after diagnosis had persistent fatigue [11]. The authors of the latter paper proposed that within the 1/3 of BCSs reporting fatigue at any time, a subgroup of women experienced “more debilitating fatigue symptoms” [11]. This is in accordance with our findings that subjects with PF had higher total fatigue scores at both assessment points compared to those with transient CF.

The findings of seeking help for mental problems prior to the BC and current psychological distress being associated with both CF and PF are in concordance with this study’s hypothesis and previous research [1, 6, 11, 15, 16, 19, 31]. Additionally, discomfort in the BC-treated area, representing both pain and/or fibrosis, was associated with CF and PF. Bower et al demonstrated that bodily pain was related to fatigue in women assessed up to 5 years post-BC treatment, and it was also a marginal predictor of fatigue at follow-up 5 years later [1, 11]. However, the location of pain was not specified. In another study, arm and shoulder pain was associated with fatigue post-BC treatment [18].

In addition to exploring self-reported factors, we also evaluated several clinical variables as possible predictors for CF and PF. We found that the median weight increase in women with CF was twice as large as in those without CF. In line with previous research [6, 7] we found that high post-BC BMI was associated with CF and a significant predictor of PF. Thus, efforts to reduce obesity in BC-treated women may contribute to lower their risk for developing persistent fatigue symptoms. The association between increased BMI and PF could also indicate a common underlying mechanism not explored in the present study design.

We observed a strong association between high hsCRP-level and treatment-area related discomfort. Therefore, only treatment-area related discomfort was entered into our final multiple logistic regression model and remained significantly associated with PF. In the univariate analysis hsCRP-level was a significant predictor of PF, with higher levels being associated with PF. Further, increased leukocyte count was associated with PF. Additionally, our data show that women with CF had higher levels of hsCRP compared to subjects without CF. Alexander et al also reported increased leukocyte count and CRP in relapse-free women with fatigue post-BC treatment, suggesting that a prolonged inflammatory response might underlie persistent fatigue [10]. Our data may also imply that an activated immune system plays a role in CF and PF, which is supported by gene expression analyses on a subsample of the women attending the present study [23]. However, a possible association between fatigue and inflammatory markers should be addressed in future studies.

We found no support for our hypothesis that young age at BC diagnosis was associated with CF or PF. Neither did we find that a diagnosis of hypothyroidism or an elevated TSH-level impacted on the women’s fatigue status. These results are in agreement with earlier research stating that abnormal thyroid function is not related to fatigue post-BC treatment [10].

We could not demonstrate any association between CF and PF and the BC treatment. However, all the included women were treated for stage II/III disease with postoperative radiotherapy, and most of them also received hormones and/or chemotherapy. Thus, our study was not optimally designed to assess the impact of different treatments upon fatigue.

A limitation of the current study is that information about the women’s fatigue status pre-BC diagnosis was not available. Therefore, we cannot conclude that fatigue was specifically related to BC. However, given the age-span relevant for the current study, CF in the general Norwegian population range from 12 to 22% [32]. Thus, CF is more prevalent in women after multimodal BC treatment than in the general population.

Even though not significant, our data indicate that the proportion of women with CF increased during the study’s time span. The women included in the current study had a higher systemic treatment burden than the non-responders. Therefore, a response bias caused by including subjects with more subjective symptoms cannot be excluded. Also in the general population the prevalence of fatigue increases with increasing age, other co-morbidities and strains of life [32]. Therefore, the observed increment in CF might be due to other factors than the BC or the BC treatment.

Also, having CF at both assessment points do not necessarily imply that the fatigue condition has been persistent during the whole observation period. However, previous papers on fatigue in BCSs used a similar approach by defining individuals with persistent fatigue as “survivors who reported significant fatigue on at least to occasions after cancer diagnosis and treatment” [21, 22, 33].

Definite information about the women’s pre-BC mental health status was not available and women visiting a psychologist/psychiatrist before their BC diagnosis were registered as having received “previous treatment for mental problems”. The survey run regularly by the Statistics Norway’s Health Interview Survey (http://www.ssb.no) reports that 4% of Norwegian females visited a psychologist/psychiatrist during the past 12 months in 1998. Thus, compared to the general Norwegian population, a considerably higher proportion (20%) of the women with CF had consulted a psychologist/psychiatrist prior to their BC diagnosis.

A recent review confirmed the association between fatigue and depression and anxiety, but the authors concluded that “directionality needs to be better delineated in longitudinal studies” [34]. Also in our study, directionality between CF and the associated factors is difficult to judge as data on the attending women’s pre-BC fatigue status were not available. However, we still consider our findings clinically important because most of the factors found at the first evaluation to be associated with the persistence of fatigue are possible targets for interventions.

Each woman was clinically examined by one oncologist. Independent oncologists examining the same individual could have allowed for estimation of the reliability of the ratings of fibrosis. However, the examination was performed by a limited number of experienced oncologists with a common scoring agreement supporting the reliability of this assessment.

Due to the relatively high number of study participants it was feasible to test multiple predictors possibly associated with PF. However, we did not have enough subjects to fit a model testing possible interactions between the variables.

Strengths of the current study are related to the long follow-up time and the longitudinal design enabling exploration of the course of CF and identification of individuals with PF as those with CF at both assessment points. Additional strength of the present study is the use of the FQ. Compared to other commonly used questionnaires assessing fatigue, the FQ has the advantage that the duration of fatigue is queried. Only subjects with symptom duration ≥6 months were defined as having CF, thus separating individuals with transient fatigue from those with more persistent symptoms. Finally, due to the unselective recruitment of patients to the hospital during the treatment period (1998–2002) and the standardized treatment they received based upon the existing national guidelines at that time, we consider the sample as representative for Norwegian women treated for BC stage II/III during the relevant treatment period.

Conclusions/ implications for breast cancer survivors

Women may experience fatigue up to 10 years after multimodal BC treatment, with about one third having CF and about one fourth having PF.

Psychological distress, high BMI and discomfort related to the BC-treated area at the first follow-up were associated with CF and significantly predicted persistence of CF at the second evaluation (i.e. PF). Therefore, efforts to improve these factors may contribute to relieve PF in BCSs.

References

Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life 1. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–53.

Loge JH, Abrahamsen AF, Ekeberg O, Kaasa S. Hodgkin’s disease survivors more fatigued than the general population. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:253–61.

Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: prevalence, correlates and interventions. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:27–43.

Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, Mustian KM, Fiscella K, Morrow GR. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12:22–34.

Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S. Breast cancer and fatigue. Sleep Med Clin. 2008;3:61–71.

Broeckel JA, Jacobsen PB, Horton J, Balducci L, Lyman GH. Characteristics and correlates of fatigue after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1689–96.

Andrykowski MA, Curran SL, Lightner R. Off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a controlled comparison. J Behav Med. 1998;21:1–18.

Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3385–91.

Stone P, Richardson A, Ream E, Smith AG, Kerr DJ, Kearney N. Cancer-related fatigue: inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-centre patient survey. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:971–5.

Alexander S, Minton O, Andrews P, Stone P. A comparison of the characteristics of disease-free breast cancer survivors with or without cancer-related fatigue syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:384–92.

Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors—A longitudinal investigation. Cancer. 2006;106:751–8.

Minton, Stone. How common is fatigue in disease-free breast cancer survivors? A systematic review of the literature. breast cancer res treat 2007.

Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–53.

Wessely S. The epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:139–51.

Geinitz H, Zimmermann FB, Thamm R, Keller M, Busch R, Molls M. Fatigue in patients with adjuvant radiation therapy for breast cancer: long-term follow-up. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:327–33.

Nieboer P, Buijs C, Rodenhuis S, Seynaeve C, Beex LVAM, van der Wall E, et al. Fatigue and relating factors in high-risk breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant standard or high-dose chemotherapy: a longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8296–304.

Fan HGM, Houede-Tchen N, Yi QL, Chemerynsky I, Downie FP, Sabate K, et al. Fatigue, menopausal symptoms, and cognitive function in women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: 1-and 2-year follow-up of a prospective controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8025–32.

Kim SH, Son BH, Hwang SY, Han W, Yang JH, Lee S, et al. Fatigue and depression in disease-free breast cancer survivors: prevalence, correlates, and association with quality of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35:644–55.

Andrykowski MA, Schmidt JE, Salsman JM, Beacham AO, Jacobsen PB. Use of a case definition approach to identify cancer-related fatigue in women undergoing adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6613–22.

Goldstein D, Bennett B, Friedlander M, Davenport T, Hickie I, Lloyd A. Fatigue states after cancer treatment occur both in association with, and independent of, mood disorder: a longitudinal study. Bmc Cancer 2006; 6

Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Cole SW, Irwin MR. Inflammatory biomarkers for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2759–66.

Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue: links with inflammation in cancer patients and survivors. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:863–71.

Landmark-Høyvik H, Reinertsen KV, Loge JH, Fossa SD, Borresen-Dale AL, Dumeaux V. Alterations of gene expression in blood cells associated with chronic fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9(5):333–40.

Reinertsen KV, Cvancarova M, Wist E, Bjøro T, Dahl AA, Danielsen T, et al. Thyroid function in women after multimodal treatment for breast cancer stage II/III: comparison with controls from a population sample. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;13:2009.

Minton O, Stone P. A systematic review of the scales used for the measurement of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) 1. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:17–25.

Stone PC, Minton O. Cancer-related fatigue. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1097–104.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Late Effects of Normal Tissues (LENT) Consensus Conference. Lent soma scales for all anatomic sites. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 1995; 31:1049–91.

Eveleth PB. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee—WHO. Am J Human Biol. 1996;8:786–7.

Servaes P, Gielissen MFM, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. The course of severe fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:787–95.

Ganz PA, Bower JE. Cancer related fatigue: a focus on breast cancer and Hodgkin’s disease survivors. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:474–9.

Loge JH, Ekeberg O, Kaasa S. Fatigue in the general Norwegian population: normative data and associations. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:53–65.

Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Fatigue and proinflammatory cytokine activity in breast cancer survivors. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:604–11.

Brown LF, Kroenke K. Cancer-related fatigue and its associations with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:440–7.

Acknowledgement

The Health Region South-East in Norway has funded the first author during her work with this paper.

Conflicts of interest

This manuscript contains original material with data not previously reported.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Reinertsen, K.V., Cvancarova, M., Loge, J.H. et al. Predictors and course of chronic fatigue in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 4, 405–414 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0145-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0145-7