Abstract

Physical products (e.g., cars, smartphones) increasingly evolve into dynamic service platforms that allow for customization through fee-based activation of restricted add-on features throughout their lifecycle. The authors refer to this emerging phenomenon as “internal product upgrades”. Drawing on normative expectations literature, this research examines pitfalls of internal product upgrades that marketers need to understand. Six experimental studies in two different contexts (consumer-electronics, automotive) reveal that consumers respond less favorably to internal (vs. external) product upgrades. The analyses show that customer-perceived betrayal, which results from increased feature ownership perceptions, drives the effects. Moreover, this research identifies three boundary conditions: it shows that the negative effects are attenuated when (1) the company (vs. consumer) executes the upgrading, and (2) consumers upgrade an intangible (vs. tangible) feature. Finally, consumers react less negatively when (3) the base product is less relevant to their self-identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“The concept of product is undergoing a rapid transformation in the digital age.”

(Kannan & Li, 2017, p. 31).

Driven by the Internet-of-Things (IoT), physical products are not static anymore. Rather, they evolve into dynamic service platforms that allow for customization throughout their lifecycle (Ng & Wakenshaw, 2017). For instance, carmakers like Tesla, Daimler/Mercedes, and Audi increasingly transform their cars into such platforms: they sell vehicles with built-in add-on features that are deliberately restricted-by-design in their function (e.g., deactivated adaptive headlights; restricted extra-battery power). Notably, for an additional fee, consumers can reconfigure their cars by activating those features over the course of their ownership.Footnote 1 We refer to this emerging phenomenon as “internal product upgrades” and define it as fee-based activation of originally built-in, but deliberately restricted, optional features. Internal product upgrades challenge the traditional way of product reconfigurationFootnote 2 through external add-ons, hereafter referred to as external product upgrades (e.g., Bertini et al., 2009; Erat & Bhaskaran, 2012). Internal and external product upgrades are similar such that in both cases an existing base product (e.g., a car) is enhanced by adding a feature (e.g., digital radio receiver). However, they differ in terms of the locus of that added feature: in the case of external product upgrades, the focal feature is physically detached and sold separately from the base product; in contrast, in the case of internal product upgrades, the focal feature is already built-in to the product the consumer has purchased, but it is deliberately restricted and can (only) be activated after the consumer pays an additional fee. Against this conceptual background, we propose that internal (vs. external) product upgrades although they ultimately result in the same functionality trigger distinct consumer responses, which marketers need to understand as they consider offering internal or external upgrades to customers.

Internal product upgrades originated in the consumer-electronics industry (e.g., for laptops or cell phones), but are now increasingly employed across industries (O'Donnell, 2017). Indeed, as Table 1 illustrates, internal product upgrades are forecasted to grow into a multi-billion-dollar business. For example, carmakers are expected to earn an additional €155 (= $184) billion by 2022 by offering consumers the opportunity to enhance their vehicle over its lifecycle; internal product upgrades also reduce production costs, as manufacturers can realize economies-of-scale by producing cars with identical features (Williams, 2017). Thus, firms anticipate internal product upgrades to provide considerable additional profit.

Despite the emerging importance of internal product upgrades in the marketplace, little marketing research has examined how consumers respond to having to pay for activating deliberately restricted features in a physical product they have already purchased, and which they therefore own. As Table 2 shows, prior research on product modifications has focused on phenomena such as external product upgrades through add-on features (i.e., separate discretionary benefits to a corresponding base product; Bertini et al., 2009; Erat & Bhaskaran, 2012; Ma et al., 2015; Ülkü et al., 2012), product versioning (i.e., deliberately subtracting functionality from a product in the manufacturing process; Deneckere & McAfee, 1996; Gershoff et al., 2012), and product upgrading (i.e., replacing an existing product with an enhanced version of the product; Okada, 2001, 2006). Moreover, some research has examined product upgrades via ‘Over-the-Air’ updates (OTA updates) (e.g., OTA updates to dispense ‘bug fixes’ and other software improvements; Foerderer & Heinzl, 2017). Although these approaches (external product upgrades, product versioning, product upgrading, OTA updates) are related phenomena, internal product upgrades are conceptually distinct such that consumers may respond differently because of key characteristics of the internal upgrade: internal features are deliberately restricted by-design, but can be activated after buying the base product by paying an additional fee; that is, internal upgrades relate to a consumer’s product/feature enhancement decision rather than a product replacement decision.Footnote 3 Notably, recent marketing research is beginning to examine how consumers respond to internal product upgrades. However, extant research has either focused on consumers’ pre-purchase responses (Wiegand & Imschloss, 2021) or investigated consumers’ feature purchase intentions for non-permanent internal product upgrades depending on (a) feature tangibility and (b) feature pricing (Schaefers et al., 2022), yet without comparing them to established post-purchase product modification. Thus, the question of how consumers react to permanent internal product upgrades in the post-purchase phase in contrast to the established way of external product upgrades remains unanswered; yet, understanding these issues is important to help firms manage the transition from external to internal product upgrades.

To address these gaps in the literature, we examine consumer responses to internal (vs. external) product upgrades by building on research on normative expectations in exchange relationships (Aggarwal, 2004) and psychological ownership (Reb & Connolly, 2007). We theorize that consumers respond negatively to internal (vs. external) product upgrades because consumers feel betrayed when they are expected to pay an additional fee to gain access to a feature that is already built into their product (i.e., their legal and/or perceived property). In short, we suggest that internal product upgrades can backfire on firms despite the potential benefits for stakeholders (e.g., firms and consumers); Table 1 illustrates this idea with anecdotal evidence of consumers responding (very) negatively to internal product upgrades.

To help marketers understand how consumers respond to internal product upgrades, we conducted six studies that examine three major questions: (1) Will internal (vs. external) product upgrades have negative effects on consumer responses? (2) Which underlying mechanisms help explain these effects? (3) How can firms mitigate negative effects of internal product upgrades? Our results show that internal (vs. external) product upgrades elicit negative effects (e.g., in terms of consumers’ behavioral intentions toward the firm; Study 1). Examining the underlying process, we demonstrate that internal product upgrades trigger perceived betrayal among consumers (Studies 2, 3A, 3B, 4 and 5) and that these negative effects result from higher levels of consumer-perceived “feature ownership” (Studies 3A, 3B, and 4). To attenuate these negative effects, we investigate different strategies related to the managerial marketing mix. Our studies show that changing the method of distribution by shifting the upgrading responsibility to the company (i.e., the company, rather than the consumer, upgrades the focal feature) helps reduce the negative effects of internal product upgrades (Study 2). Furthermore, investigating a product strategy, our findings suggest that internal product upgrades are more detrimental for tangible (vs. intangible) features (Study 4). Our final study (that surveys actual customers of a large car-leasing firm) suggests that managers should take the product’s relevance for a consumer’s identity into account when offering tangible (vs. intangible) product upgrades (Study 5).

Our research makes several contributions. First, examining how consumers react to internal (vs. external) product upgrades, we reveal its systematic negative impact on consumers’ responses in the post-purchase stage. Prior work on product modifications largely focused on consumer responses in a pre-purchase stage (Bertini et al., 2009; Gershoff et al., 2012; Wiegand & Imschloss, 2021), and the few studies on post-purchase responses either examined external product upgrades (Liu et al., 2018), non-built-in software applications (Erat & Bhaskaran, 2012; Yoo et al., 2012), or non-permanent internal product upgrades without comparing them to established product reconfiguration approaches (Schaefers et al., 2022). As such, our research expands the literature on product modifications in general (Bertini et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2015), and it responds to calls for more research on product reconfigurations (Ng & Wakenshaw, 2017).

Second, we explore the underlying process that helps explain the unfavorable consumer response to this new after-sales revenue model: we find internal product upgrades can elicit consumer-perceived betrayal, which arise due to increased perceived feature ownership, and ultimately drives negative downstream effects (e.g., consumer intentions toward the firm).

Third, we investigate conceptually and managerially relevant boundary conditions that revolve around different elements of the managerial marketing mix; specifically, we test three moderating factors (i.e., upgrading responsibility, feature tangibility, and the base product’s relevance for consumer identity). Our findings on these moderators not only help managers identify consumer segments that respond relatively more favorably to internal product upgrades, but also point to actionable strategies that help alleviate their negative effects.Footnote 4

Literature review

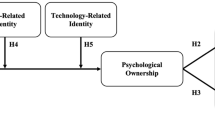

Product modifications in the post-purchase stage are increasingly relevant for firms, as they are a means for after-sales revenue (Ellison, 2005). To date, separately sold external add-on features that enhance the value of an existing base product (e.g., additional memory cards for cell phones) are the dominant approach toward post-purchase product modifications. Accordingly, marketing research on post-purchase product modifications has focused on such external product upgrades. For example, some research has examined how the availability of external add-on features influences the evaluation of the base product in the pre-purchase stage (Bertini et al., 2009). Other work (Erat & Bhaskaran, 2012; Liu et al., 2018) focused on the post-purchase stage itself and examined how base product or add-on pricing influences the decision to purchase the add-on feature or the future replacement of the base product. Recently, some initial research investigated internal product upgrades. For instance, Wiegand and Imschloss (2021) examined how consumers’ attitude and purchase intentions for the base product in the pre-purchase phase differ for internal product upgrades that are sold permanently for a one-time fee versus temporarily for rent. Instead, Schaefers et al. (2022) focused on the post-purchase phase to investigate consumers’ purchase intentions for non-permanent internal product upgrades depending on a feature’s tangibility (tangible vs. intangible) and feature pricing (monthly subscription vs. pay-per-use). These prior studies offer valuable insights into product modifications (as Table 2 shows), but they do not explain how consumers respond to internal vs. external product upgrades after they have purchased (and therefore own) the focal base product. To extend the literature, we draw on insights about consumers’ normative expectations and propose the conceptual framework in Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework. Consumer responses to product upgrade locus in light of boundary conditions based upon elements of the marketing mix (i.e., distribution and product strategy) from a normative expectations perspective. S1, S2, S3A, S3B, S4, and S5 stand for the studies that demonstrate the corresponding effects

Hypotheses: Internal product upgrades and normative expectations

Exchange relationships between consumers and firms are governed by distinct norms (Aggarwal, 2004). Norms are implicit, stable rules and guiding principles that function as a lens to evaluate the appropriateness of a firm’s actions (Aggarwal & Zhang, 2006; Maxwell, 1999). Typically, the underlying norm within exchange relationships implies that both, consumers and firms, provide comparable benefits in return for received benefits (i.e., quid pro quo; Aggarwal, 2004). Hence, exchange relationships focus on the balance of inputs relative to outcomes (Clark & Mills, 1993).Footnote 5 As a reference point to evaluate whether a firm adheres to these norms and whether it treats consumers fairly, consumers often consider their previous marketplace experiences (Kahneman et al., 1986; Xia et al., 2004).

Traditionally, once a consumer has purchased a physical good in exchange relationships, a full transfer of ownership occurred (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012). With ownership, consumers are used to acquiring full property rights over the purchased object (including the right to use all its built-in components; Snare, 1972). However, as internal product upgrades are making products more reconfigurable after the purchase, ownership boundaries become blurred. Although a consumer may have no legal claim to use a focal feature without paying an extra fee, we expect that internal product upgrades nevertheless elicit psychological ownership for internal features as these features are built-into the base product, which customers have purchased and consider their property. This idea is consistent with research suggesting that psychological ownership is inherent within an individual and that legal ownership is not a necessary condition for psychological ownership (e.g., Reb & Connolly, 2007).

Consequently, in the case of internal product upgrades, we expect that the fee-based activation of a focal feature, which is perceived to be part of one’s property, can elicit perceptions of betrayal (i.e., a norm violation) because consumers expect to have free access to it and thus believe they have to pay extra to use their own property. Perceived betrayal is defined as “[…] a customer’s belief that a firm has intentionally violated what is normative in the context of their relationship” (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008, p. 250). In contrast, we theorize that external product upgrades will not elicit similar perceptions of betrayal as the external feature is a separate item that is not already part of the consumer’s purchased product (Bertini et al., 2009; Erat & Bhaskaran, 2012; Liu et al., 2018). Research on exchange relationships suggests that these perceptions of betrayal, in turn, motivate consumers to restore fairness (e.g., by punishing or causing inconveniences to the firm; Grégoire & Fisher, 2008; Grégoire et al., 2009; Ward & Ostrom, 2006). Against this background, we expect that consumers respond less favorably to internal (vs. external) product upgrades in terms of their willingness-to-pay for the feature (WTP) and their loyalty intentions toward the firm, two managerially relevant outcome variables that are widely studied in marketing (e.g., Atasoy & Morewedge, 2017; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Grégoire et al., 2009). We hypothesize:

H1

Consumers will respond less favorably (in terms of WTP or loyalty intentions) to internal (vs. external) product upgrades.

H2a

The effect of internal (vs. external) product upgrades on consumers’ downstream responses will be mediated by perceived betrayal.

H2b

The effect of internal (vs. external) product upgrades on consumers’ downstream responses will be serially mediated such that internal (vs. external) product upgrades lead to higher perceived feature ownership, which leads to higher perceptions of betrayal, which ultimately drive consumers’ downstream responses.

Overview of studies

We conducted six studies across two contexts (consumer-electronics and automotive) to examine our hypotheses (see Table 3). Study 1 provides initial evidence of consumers’ negative behavioral response to internal (vs. external) product upgrades in a consumer-electronics context (H1). Study 2 sheds light on the underlying psychological mechanism via perceived betrayal (H2a) and investigates a managerial intervention related to distribution strategy. Specifically, it examines whether shifting the upgrading responsibility away from consumers and toward the firm can attenuate the negative effects of internal product upgrades (H3, to be introduced below). Next, Studies 3A and 3B demonstrate the serial mediation via perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal (H2b). Study 3B also rules out several alternative explanations (e.g., cost/effort perceptions, environmental friendliness). Study 4 tests the moderating role of feature tangibility (i.e., whether negative effects of internal product upgrades are buffered for features that are more intangible; H4; product strategy). Finally, Study 5 offers segmentation criteria that allow firms to target consumers who are more likely to respond more favorably to internal product upgrades related to the low (vs. high) identity-relevance of the base product (H5); we demonstrate this moderating effect with customers of a global car-leasing company.

Study 1: Effects of internal versus external product upgrades on consumers

The purpose of Study 1 is to investigate the impact of upgrade locus (internal vs. external) on consumer responses (H1).

Design, participants, and procedure

The experiment employed a 2(upgrade locus: internal, external) between-subjects design. We used a familiar consumer-electronics context (base product: smartphone, added feature: memory chip) for external validity (Sela & LeBoeuf, 2017). We recruited 149 smartphone owners (Mage = 46.36, 44.3% female) of a consumer panel provider with a high-quality recruitment process and randomly assigned them to one of the two conditions. Participants were asked to imagine that they had recently bought a 64 GB smartphone (i.e., base product) and were interested in upgrading its memory by purchasing an additional 32 GB of memory (i.e., added feature). An excerpt of the manipulation is as follows, a subtle manipulation with only five words changed across conditions (see Web Appendix A for full stimuli):

“The memory chip that is required for the extra 32 GB [was already / was not] physically built-into the phone when you purchased it. To obtain the extra memory, you have to pay a fee; the [internal / external] memory chip can then be [activated in / incorporated into] your phone.”

Study 1 also aims to rule out the alternative explanation of reusability of the external feature; we informed participants that the memory upgrade is only available for use in their current phone (i.e., the external chip is non-reusable).

We measured participants’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) for the additional memory in an open-ended format with “Please indicate the maximum amount you would be willing to pay for the [added feature]” (e.g., Atasoy & Morewedge, 2017). We also measured loyalty intentions toward the firm (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Grégoire & Fisher, 2006) (See Appendix A for all measures in this and subsequent studies). As a manipulation check, participants indicated if they perceived the added feature to be internal or external to the product; specifically, we measured participants’ perception of spatial proximity of the added feature to the base product with a slider ranging from 0 (not part of the smartphone) to 100 (part of the smartphone). Finally, participants indicated their demographics (gender and age).

Results

Manipulation check

ANOVA showed that the proximity of the added feature to the base product was significantly higher for internal (vs. external) features (Minternal = 79.17 vs. Mexternal = 12.59; F(1, 147) = 195.64, p < 0.001). The means also were significantly different from the scale midpoint (i.e., 50; ps < 0.001). Thus, the manipulation performed as intended.

Willingness-to-Pay

We conducted an ANCOVA on WTP,Footnote 6 as a function of upgrade locus, controlling for gender and age.Footnote 7 Results showed a significant upgrade locus main effect (Minternal = 2.24 vs. Mexternal = 2.85; F(1, 145) = 8.34, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.05); consumers in the internal (vs. external) product upgrade condition reported a significantly lower WTP.

Loyalty intentions

Similarly, an ANCOVA revealed that loyalty intentions toward the firm were lower with an internal (vs. external) product upgrade (Minternal = 5.18 vs. Mexternal = 5.80; F(1, 145) = 10.15, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.07).

Discussion

In support of H1, Study 1 reveals the negative effect of internal product upgrades on consumer responses. These findings provide initial support for our prediction that consumers evaluate internal product upgrades less favorably than external ones. Extending these initial insights, the goal of Study 2 is threefold: First, we investigate the psychological mechanism underlying the negative response to internal (vs. external) upgrades: perceived betrayal (H2a). Second, Study 2 tests a buffering strategy (i.e., upgrading responsibility) to mitigate the negative effects of internal product upgrades (H3, introduced next). Third, using a different context (i.e., cars), we aim to illustrate the generalizability of our results from Study 1.

Study 2: The moderating role of upgrade responsibility

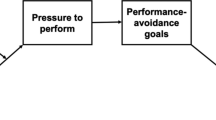

The extent to which consumers perceive a norm violation in an exchange relationship is contingent on the salience of the focal violation (Gershoff et al., 2012; Xia et al., 2004). Thus, to reduce negative reactions, firms need to reduce the salience of the norm violation. Notably, firms can do so using elements of the marketing mix as shown by Gershoff et al. (2012). We build on this idea and investigate several managerially relevant strategies that relate to the marketing mix. In Study 2, we focus on a distribution strategy first: we propose that one viable strategy to mitigate unfavorable effects might be to shift the responsibility for the upgrade from the consumer to the firm. Internal product upgrades over the course of the product’s lifecycle can be co-created by consumers because upgrading the product is a self-service; that is, consumers themselves can perform the upgrade via their computer or smartphone (e.g., Tesla and Audi). This is in line with Ng and Wakenshaw’s (2017) conceptualization of dynamic service platforms, which are designed to have customizable functionalities that can (or have to) be changed by consumers themselves; it is also consistent with the increasingly service-dominated economy and the related servitization of goods (Vargo & Lusch, 2017). However, we expect that as consumers pay for and perform this self-service upgrade it will become salient to them that the performance-boosting feature is already physically embedded in their product (i.e., the product they already paid for when they bought it) and is literally just a fingertip (and a credit card transaction) away from use. In contrast to this self-service solution, having the firm perform the product upgrade reduces this salience, as consumers might not fully comprehend which procedures companies complete to upgrade the product. Therefore, we expect that shifting the upgrading responsibility from the consumer to the firm attenuates the negative effects of internal product upgrades:

H3

-

When performing the upgrade is the consumers’ (self-service) responsibility, they will respond less favorably to internal (vs. external) product upgrades; this effect will be attenuated when the company is responsible for performing the upgrade.

Design, participants, and procedure

Study 2 employed a 2(upgrade locus: internal, external) × 2(upgrading responsibility: consumer, company) between-subjects design. Car owners (N = 330, Mage = 34.56, 50.0% female) of a professional online consumer panel were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. Participants were asked to imagine that they recently bought a car (i.e., base product) of a well-established brand. We asked participants to imagine being interested in upgrading their car’s infotainment system by purchasing a digital radio (i.e., feature upgrade). We manipulated upgrade locus as follows: in the internal product upgrade conditions, every car had a built-in radio receiver, which was deactivated; consumers must pay a fee to activate it. In the external upgrade conditions, consumers must pay for an external radio receiver.

We manipulated upgrading responsibility by describing the upgrading task as being performed by either the consumer or the company (see Web Appendix A). In the consumer-conditions, consumers could upgrade the functionality themselves either by purchasing and thereby activating the digital radio receiver via the company’s online shop (internal product upgrade), or by purchasing and physically adding it to the car (external product upgrade). In the company-conditions, the digital radio receiver is purchased from and activated (vs. purchased and physically installed) by the car company’s dealership.

In addition to their WTP for the added feature, participants also indicated their perceptions of betrayal (Bardhi et al., 2005; Grégoire & Fisher, 2008). Finally, they answered the same manipulation check as in Study 1, and provided demographics (i.e., gender and age).

Pretest

We ran a study to test the company responsibility manipulation, (N = 82, Mage = 46.01, 45.1% female) in which we assessed consumers’ perception of company responsibility (measure adapted from Botti & McGill, 2006). A two-way ANOVA on company responsibility showed a significant upgrading responsibility main effect (Mconsumer = 2.14 vs. Mfirm = 4.69; F(1, 78) = 47.39, p < 0.001). The upgrade locus main effect (F(1, 78) = 1.52, p = 0.22) and interaction (F(1, 78) = 0.191, p = 0.17) were NS, indicating a successful manipulation.

Results

Manipulation check

An upgrade locus × upgrading responsibility ANOVA revealed a significant upgrade locus main effect on proximity (Minternal = 57.96 vs. Mexternal = 17.01; F(1, 326) = 141.87, p < 0.001). The upgrading responsibility main effect (F(1, 326) = 0.63, p = 0.43) and interaction (F(1, 326) = 0.59, p = 0.44) were NS. The means also significantly differed from the midpoint (i.e., 50; ps < 0.01); indicating a successful manipulation of upgrade locus.

Willingness-to-Pay

An ANCOVA on WTP revealed a significant two-way interaction (F(1, 324) = 4.60, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01), and a significant upgrading responsibility main effect (F(1, 324) = 6.00, p < 0.05). The upgrade locus main effect is NS (F(1, 324) = 1.96, p = 0.16).

When the upgrade is the consumer’s responsibility, WTP for internal product upgrades is significantly lower (Minternal,consumer = 3.44 vs. Mexternal,consumer = 4.08; F(1, 324) = 5.93, p < 0.05), replicating the previous findings and supporting H1. However, when the upgrade is the company’s responsibility, WTP for internal vs. external product upgrades did not differ (Minternal,company = 4.28 vs. Mexternal,company = 4.14; F(1, 324) = 0.29, p = 0.59). Furthermore, under the internal upgrade locus condition, WTP was significantly lower when it was the consumer’s (vs. company’s) responsibility (Minternal,consumer = 3.44 vs. Minternal,company = 4.28; F(1, 324) = 10.20, p < 0.01); however, under the external upgrade locus, WTP was unaffected (Mexternal,consumer = 4.08 vs. Mexternal,company = 4.14; F(1, 324) = 0.05, p = 0.83). See Fig. 2A.

Note. When the upgrade is the consumers’ responsibility, they are willing to pay less for an internal (vs. external) product upgrade; when the upgrade is the firm’s responsibility, WTP is relatively unaffected (Panel A). The effects on WTP are driven by the greater magnitude of perceived betrayal when the consumer is responsible for implementing the upgrade (Panel B). (Significant and marginally significant contrasts are noted by bars accordingly in the figures)

Perceived betrayal

An ANCOVA on perceived betrayal showed a significant two-way interaction (F(1, 324) = 4.01, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01) and upgrade locus main effect (F(1, 324) = 18.58, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05); the responsibility main effect was NS (F(1, 324) = 0.01, p = 0.93).

When the upgrade is the consumers’ responsibility, they felt significantly more betrayed by an internal (vs. external) product upgrade (Minternal,consumer = 4.05 vs. Mexternal,consumer = 2.85; F(1, 324) = 18.82, p < 0.001). When it is the company’s responsibility, perceived betrayal for internal vs. external product upgrades was weaker (Minternal,company = 3.66 vs. Mexternal,company = 3.22; F(1, 324) = 2.84, p < 0.10) (see Fig. 2B).

Moderated mediation analysis

We estimated the indirect effect of upgrade locus × upgrading responsibility on WTP through perceived betrayal with PROCESS Model 7 (5,000 resamples; Hayes, 2017). Results showed that perceived betrayal mediates the effects of the two-way interaction on WTP (moderated mediation index = 0.1987, 95% CI = [0.0068, 0.4573]). Perceived betrayal mediates for consumer self-upgrading (a × b = − 0.3135, 95% CI = [− 0.5724, − 0.1255]), but not for company upgrading (a × b = − 0.1148, 95% CI = [− 0.2812, 0.0149]).

Discussion

Supporting H2a, Study 2 shows that consumers’ perceived betrayal mediates the relationship of upgrade locus and behavioral responses. Moreover, in line with Study 1 (H1), Study 2 shows that having consumers upgrade their products internally (vs. externally) themselves triggers negative responses. Importantly, shifting the upgrading responsibility away from the consumer (and toward the company) attenuates the negative effects, in support of H3. As such, Study 2 identifies one approach that managers can employ to attenuate the negative effect of internal product upgrades. Finally, by using an automotive context we illustrate the generalizability of our results, while also drawing on marketplace realities of firms already using these forms of upgrades (e.g., Tesla, Audi, and Daimler/Mercedes).

Study 3: Perceived feature ownership as a driver of perceived betrayal

Study 2 sheds light on one part of the proposed underlying process (i.e., perceived betrayal). Extending this insight, Studies 3A and 3B now investigate the entire serial mediation. We expect that perceptions of betrayal (as shown in Study 2) arise due to increased feature ownership perceptions for internal (vs. external) product upgrades (H2b). Moreover, Study 3B rules out alternative explanations that might drive our effects.

Study 3A

Study 3A Design, participants, and procedure

Study 3A employed a 2(upgrade locus: internal, external) between-subjects design, using a smartphone context, as in Study 1 (base product: smartphone, added feature: memory chip; see Web Appendix A). We recruited 335 smartphone owners (Mage = 41.35, 50.4% female) from a consumer panel as in Study 1. After reading the scenario about upgrading the phone’s memory, participants indicated their WTP, loyalty intentions toward the firm, and perceptions of betrayal. They also indicated their level of psychological ownership for the added feature (Peck & Shu, 2009) (See Appendix A). Finally, participants completed the manipulation check and indicated their demographics (i.e., gender and age).

Study 3A Results

Manipulation check

ANOVA on proximity of the added feature showed that proximity to the base product was significantly higher for internal (vs. external) features (Minternal = 77.14 vs. Mexternal = 16.66; F(1, 333) = 367.86, p < 0.001). The means were significantly different from the scale midpoint (i.e., 50; ps < 0.001). Thus, the manipulation was successful.

Willingness-to-Pay

We conducted an ANCOVA on WTP, as a function of upgrade locus, controlling for gender and age. Consumers in the internal (vs. external) product upgrade condition reported a significantly lower WTP (Minternal = 2.52 vs. Mexternal = 2.84; F(1, 331) = 8.17, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.02), supporting H1.

Loyalty intentions

An ANCOVA showed that loyalty intentions were lower with an internal (vs. external) product upgrade (Minternal = 4.36 vs. Mexternal = 5.03; F(1, 331) = 18.64, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05), supporting H1.

Perceived feature ownership

An ANCOVA on perceived feature ownership showed that participants perceived significantly more ownership for the internal feature than for the external feature (Minternal = 5.04 vs. Mexternal = 2.82; F(1, 331) = 110.51, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.25).

Perceived betrayal

An ANCOVA on perceived betrayal showed that participants in the internal (vs. external) product upgrade condition felt significantly more betrayed (Minternal = 3.59 vs. Mexternal = 2.76; F(1, 331) = 18.52, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05).

Mediation analyses

To test the underlying processes, we conducted serial mediation analyses on each outcome variable (PROCESS Model 6; 5,000 resamples; Hayes, 2017), estimating the indirect effects of upgrade locus on (1) WTP and (2) loyalty intentions through perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal. Results revealed the predicted serial mediation paths on WTP (internal product upgrade → higher feature ownership perceptions → increased perceived betrayal → reduced WTP); a × b = − 0.0957, 95% CI = [− 0.1639, − 0.0416]. There was also a significant serial mediation on loyalty intentions (internal product upgrade → higher feature ownership perceptions → increased perceived betrayal → reduced loyalty intentions); a × b = − 0.3066, 95% CI = [− 0.4507, − 0.1936]. These results are consistent with H2b.

Study 3A Discussion

In support of H1 and H2b, Study 3A sheds light on the psychological mechanism driving consumers perceptions of betrayal in light of internal product upgrades: it reveals that internal (vs. external) product upgrades elicit higher perceptions of feature ownership, which trigger perceptions of betrayal, and ultimately result in less favorable consumer responses.

Study 3B

The goal of Study 3B was twofold. First, we intend to replicate the effects in Study 3A, while also ruling out alternative explanations, namely that our effect relies (1) on consumers’ cost evaluations (i.e., perceived production effort and upgrading effort) or (2) the environmental friendliness of the upgrade.Footnote 8 For exploratory purposes, we also examine five other potential alternative explanations (i.e., perceived convenience, performance risks, failure severity, value-in-use, and perceived greed). Second, we utilize the more subtle upgrade locus manipulation from Study 1, which does not explicitly tell consumers that the feature was actively deactivated by the company. As such, we avoid inducing an artificial negative effect of internal product upgrades when testing the full serial mediation model.

Study 3B Design, participants, and procedure

The experiment employed a 2(upgrade locus: internal, external) between-subjects design. We recruited smartphone owners (N = 272, Mage = 47.06, 40.8% female) using the same context (i.e., base product: phone, added feature: memory chip), consumer panel, and procedure as in Study 1 (see Web Appendix A). We used the same measures for WTP, loyalty intentions, feature ownership, betrayal, and the manipulation check as in Study 3A. Finally, participants indicated demographics (i.e., gender and age). (See Appendix A for items.)

Study 3B Results

Manipulation check

ANOVA on proximity of the added feature showed that proximity to the base product was significantly higher for internal (vs. external) features (Minternal = 72.52 vs. Mexternal = 15.88; F(1, 270) = 227.30, p < 0.001). The means were also significantly different from the scale midpoint (i.e., 50; ps < 0.001). Thus, our manipulation was successful.

Willingness-to-Pay

We conducted an ANCOVA on WTP as a function of upgrade locus. Results showed the predicted significant effect for upgrade locus on WTP (Minternal = 2.13 vs. Mexternal = 2.69; F(1, 268) = 12.47, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04); that is, consumers in the internal (vs. external) product upgrade condition reported a significantly lower WTP.Footnote 9

Loyalty intentions

An ANCOVA on loyalty intentions revealed similar significant results. Loyalty intentions toward the firm were lower with an internal (vs. external) product upgrade (Minternal = 4.64 vs. Mexternal = 5.45; F(1, 268) = 26.04 p < 0.001, η2 = 0.09).

Perceived feature ownership

An ANCOVA on perceived feature ownership revealed that participants had significantly higher feature ownership perceptions for the internal versus the external feature (Minternal = 4.86 vs. Mexternal = 3.89; F(1, 268) = 14.87, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05).

Perceived betrayal

An ANCOVA on perceived betrayal showed that participants in the internal (vs. external) product upgrade condition felt significantly more betrayed (Minternal = 3.57 vs. Mexternal = 2.38; F(1, 268) = 29.60, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10).

Mediation analyses

We conducted serial mediation analyses on each outcome variable (PROCESS Model 6; 5,000 resamples; Hayes, 2017), estimating the indirect effects of upgrade locus on WTP and loyalty intentions through perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal, controlling for age and gender. As in Study 3A, results showed the predicted serial mediation paths on WTP (internal product upgrade → higher feature ownership perceptions → increased perceived betrayal → reduced WTP); a × b = − 0.0310, 95% CI = [− 0.0676, − 0.0077]. We also find a significant serial mediation on loyalty intentions (internal product upgrade → higher feature ownership perceptions → increased perceived betrayal → reduced loyalty intentions); a × b = − 0.0730, 95% CI = [− 0.1426, − 0.0223].

Alternative explanations

To test whether our results (serial mediation via feature ownership perceptions and perceived betrayal), are stable even if we consider the potential alternative explanations, as mentioned in footnote 8, (1) we controlled for the variables in the serial mediation models, (2) we included the variables as parallel mediators in the serial mediation model, (3) we analyzed the relationship between perceived betrayal and two different measures of greed, and (4) we further analyzed value-in-use. Results robustly showed the predicted serial mediation path even if we control for the potential alternative explanations (simultaneously or individually) or include them as parallel mediators. Please see Web Appendix D for complete analyses.

Study 3B Discussion

Study 3B provides three main insights: First, replicating the findings of Study 3A, Study 3B shows that internal (vs. external) product upgrades elicit higher perceptions of feature ownership, which trigger perceived betrayal and ultimately undermine consumer responses. Second, we replicate our findings with an arguably more subtle manipulation, which suggests that our effects are robust. Third, Study 3B shows that the negative (serial mediation) effects of internal product upgrades cannot be attributed to potential alternative explanations, such as cost perceptions or environmental friendliness (see Web Appendix D).

Study 4: The moderating role of feature tangibility

So far, our results demonstrate that consumers feel betrayed when they are confronted with internal (vs. external) upgrades for tangible features like memory chips or digital radio receivers (Studies 2, 3A, and 3B) and that this betrayal results from perceived feature ownership (Studies 3A and 3B). Moreover, Study 2 demonstrated that the negative effects of internal product upgrades can be attenuated via a distribution-related strategy (i.e., upgrading responsibility). We now investigate a product-related strategy and propose that feature tangibility (i.e., the degree to which a feature is more dominated by tangible (e.g., hardware) rather than intangible (e.g., software) elements; Laroche et al., 2001) moderates how consumers respond to internal product upgrades. Prior research shows that ownership perceptions are contingent on product tangibility. Specifically, products high in tangibility create greater ownership perceptions than products low in tangibility (Atasoy & Morewedge, 2017). Building on this notion, we expect that consumers should feel less ownership for an intangible (vs. a tangible) feature in a purchased product. Consequently, consumers should perceive internal upgrades for intangible features as less norm violating and, thus, react less negatively to internal (vs. external) upgrades for intangible features (e.g., driving performance software) than for tangible features (e.g., rear-view camera). We hypothesize:

H4

In the context of an upgrade of a feature that is perceived to be highly tangible, consumers will respond less favorably to internal (vs. external) product upgrades; this effect will be attenuated for product upgrades of features that are perceived to be highly intangible.

Design, participants, and procedure

To test H4, we ran a 2(upgrade locus: internal, external) × 2(feature tangibility: tangible, intangible) between-subjects design. Car owners (N = 476, Mage = 34.99, 53.2% female) of a professional online consumer panel were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. Participants were asked to imagine that they recently bought a car (i.e., the base product) of a well-established brand with an excellent reputation. We manipulated feature tangibility by asking them to imagine being interested in upgrading their car’s basic technology system by purchasing either a rear-view camera (i.e., tangible feature condition) or a driving performance software (i.e., intangible feature condition). We manipulated upgrade locus similar to our previous studies. In the internal upgrade conditions, every car came equipped with a built-in camera (tangible feature) or with the driving performance software already pre-installed (intangible feature); yet, both these features (camera and software) were deliberately deactivated. To obtain the respective feature, consumers have to pay a fee to activate it. In the external product upgrade conditions, consumers pay for an external camera sensor (tangible feature) or for the installation of the software (intangible feature).

We used the same measures for loyalty intentions, feature ownership, and betrayal as in our previous studies. Participants provided demographics (i.e., gender and age); because we used two distinct features (i.e., rear-view camera and driving performance software), we also measured perceived feature centrality to the base product as a control variable (Bertini et al., 2009; Cox & Cox, 2002). Participants also answered the upgrade locus manipulation check and a manipulation check for perceived feature tangibility (i.e., “The [feature] is a … (1) digital product, (7) physical product”, Schmitt, 2019; Shostack, 1977).

Results

Manipulation check

An upgrade locus × feature type ANOVA on perceived feature tangibility revealed a significant main effect of feature type (Mtangible = 4.30 vs. Mintangible = 1.99; (F(1, 472) = 185.98, p < 0.001). The upgrade locus main effect (F(1, 472) = 2.18, p = 0.14) and the interaction (F(1, 472) = 0.62, p = 0.43) were NS. Thus, the manipulation was successful.

Loyalty intentions

A two-way ANCOVA on loyalty revealed a significant upgrade locus × feature tangibility interaction (F(1, 469) = 3.86, p = 0.05, η2 = 0.01). We also found significant main effects of upgrade locus (F(1, 469) = 5.06, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01) and feature tangibility (F(1, 469) = 12.62, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03).

In the tangible feature conditions, loyalty intentions for internal product upgrades were significantly lower (Minternal,tangible = 4.32 vs. Mexternal,tangible = 4.78; F(1, 469) = 9.40, p < 0.01), replicating previous studies and supporting H1. However, in the intangible feature conditions, loyalty intentions for internal (vs. external) upgrades did not differ (Minternal,intangible = 4.95 vs. Mexternal,intangible = 4.99; F(1, 469) = 0.04, p = 0.84). Looked at another way, in the internal upgrade conditions, loyalty intentions were significantly lower for a tangible (vs. intangible) upgrade (Minternal,tangible = 4.32 vs. Minternal,intangible = 4.95; F(1, 469) = 15.25, p < 0.001); in the external upgrade conditions (Mexternal,tangible = 4.78 vs. Mexternal,intangible = 4.99; F(1, 469) = 1.69, p = 0.19), loyalty was relatively unaffected; see Fig. 3A.

Note. Consumers show less favorable loyalty intentions for an internal (vs. external) product upgrade when the focal feature is tangible (vs. intangible) (Panel A). Perceived feature ownership is higher for internal (vs. external) product upgrades of tangible (vs. intangible) features (Panel B). Consumers feel more betrayed when being confronted with an internal (vs. external) product upgrade; this effect is attenuated for feature intangibility (Panel C)

Perceived feature ownership

An upgrade locus × feature tangibility ANCOVA on perceived feature ownership showed a significant interaction effect (F(1, 469) = 9.32, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.02). The analysis also found a significant main effect of upgrade locus (F(1, 469) = 61.98, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.12) and feature tangibility (F(1, 469) = 6.22, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01).

In the tangible feature condition, consumers felt significantly more feature ownership for internal (vs. external) upgrades (Minternal,tangible = 4.94 vs. Mexternal,tangible = 3.02; F(1, 469) = 63.28, p < 0.001), replicating our prior findings. In the intangible feature conditions, perceived ownership for internal (vs. external) upgrades was also significantly different (Minternal,intangible = 3.92 vs. Mexternal,intangible = 3.07; F(1, 469) = 11.04, p < 0.01). Looked at another way, for internal upgrades, perceived feature ownership was significantly greater for tangible (vs. intangible) features (Minternal,tangible = 4.94 vs. Minternal,intangible = 3.92; F(1, 469) = 14.92, p < 0.001). However, for external upgrades, perceived feature ownership was relatively unaffected (Mexternal,tangible = 3.02 vs. Mexternal,intangible = 3.07; F(1, 469) = 0.05, p = 0.82); see Fig. 3B.

Perceived betrayal

An ANCOVA on perceived betrayal showed a significant upgrade locus × feature tangibility interaction (F(1, 469) = 6.27, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01). The main effects of upgrade locus (F(1, 469) = 11.88, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03) and feature tangibility (F(1, 469) = 3.89, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01) were significant as well.

When the upgrade was for a tangible feature, consumers felt significantly more betrayed in the context of internal (vs. external) upgrades (Minternal,tangible = 3.60 vs. Mexternal,tangible = 2.71; F(1, 469) = 18.76, p < 0.001), replicating our previous findings. When upgrading an intangible feature, perceived betrayal was not different for internal (vs. external) product upgrades (Minternal,intangible = 2.91 vs. Mexternal,intangible = 2.76; F(1, 469) = 0.42, p = 0.52). Looked at another way, for internal upgrades, perceived betrayal was significantly higher for tangible (vs. intangible) features (Minternal,tangible = 3.60 vs. Minternal,intangible = 2.91; F(1, 469) = 9.71, p < 0.01). However, for external upgrades, perceived betrayal was relatively unaffected (Mexternal,tangible = 2.71 vs. Mexternal,intangible = 2.76; F(1, 469) = 0.06, p = 0.81); see Fig. 3C.

Moderated serial mediation analysis

We estimated the indirect effect of upgrade locus × feature tangibility on loyalty intentions through perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal, controlling for gender, age, and feature centrality with PROCESS Model 83 (5,000 resamples; Hayes, 2017). Results revealed a significant serial mediation via perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal of the two-way interaction on loyalty intentions (moderated mediation index = 0.1383, 95% CI = [0.0463, 0.2505]). We found a significant serial mediation via perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal in the context of upgrading a tangible feature (a × b = − 0.2477, 95% CI = [− 0.3554, − 0.1553]), replicating our findings from Study 1. The results also revealed a smaller indirect effect when consumers were able to upgrade an intangible feature (a × b = − 0.1094, 95% CI = [− 0.1924, − 0.0397]). These results support H4.

Discussion

As predicted by H4, Study 4 shows that feature tangibility influences the impact of upgrade locus on consumers’ responses. In line with H1, internal (vs. external) upgrades elicit less favorable behavioral responses for tangible features. Yet, the negative effect of internal product upgrades is mitigated for intangible features, as customers perceive less ownership of an intangible (vs. a tangible) feature and, in turn, feel less betrayed.

Study 5: How the relevance of products for consumers’ identity can influence customers’ responses to internal product upgrades

Across the studies thus far, we showed a robust effect that internal (vs. external) product upgrades can result in negative consumer responses. Our final study, in which we worked with a partner firm to survey their actual customers, has three objectives: First, it draws on research that has shown that products (e.g., cars) can be important for consumer identity (Belk, 1988; Ferraro et al., 2011). Thus, Study 5 examines whether the relevance of a product (i.e., a car) for a consumer’s identity is another boundary condition that affects how consumers respond to internal product upgrades, either tangible or intangible. Second, this study is a highly conservative test of our theory as it investigates whether internal product upgrades can backfire even in non-ownership contexts (i.e., with consumers who are leasing their car rather than having purchased it), and whether it might even cause negative spillover effects for companies beyond the manufacturer of the base product (e.g., spillover to car leasing companies). As consumers come to intimately know the object (e.g., their car), control it, and invest themselves to a certain extent (Bagga et al., 2019; Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Fritze et al., 2020), we expect that consumers’ negative responses will emerge even in a non-ownership context (i.e., a leased car). Third, we seek to increase external validity for the findings of Study 4 by surveying actual customers of a global car leasing company who are periodically surveyed regarding new product and service ideas.

When conducting the study, we focused exclusively on internal upgrades for several reasons. First, Study 4 shows that internal product upgrades are more detrimental for tangible (vs. intangible) features, whereas external upgrades are relatively unaffected. Second, while external product upgrades have been the dominant way of product upgrades in the past and are a suitable reference group, in practice, internal product upgrades are increasingly prevalent, and major car manufacturers have made it their mission to integrate advanced digital technologies to enhance customer experience (BMW, 2020). Third, since we are working with a partner firm to conduct a study with their actual customers, the design was guided by what they felt was the more pressing topic to unpack for their business needs.

The product’s relevance for consumers identity and feature tangibility perceptions

Whether or not consumers react negatively to internal product upgrades of tangible features may be contingent on how relevant the product is for their self-identity (Atasoy & Morewedge, 2017; Coulter et al., 2003). The more relevant a product is for the consumers’ identity, the more they should value this material possession, which increases their sense of psychological ownership. For instance, Belk (1988, 2013) argues that material possessions that are highly relevant to a person’s self-identity become part of the extended self and losing them results in a loss of some aspect of the self (Belk, 1988; Ferraro et al., 2011). In a similar vein, Atasoy and Morewedge (2017) find that consumers who strongly relate to a product prefer a physical (i.e., tangible) over a digital (i.e., intangible) format of that product, because they can integrate physical products more easily into their self-identity, establishing higher perception of psychological ownership.

Building on these findings, we expect that the higher a base product’s relevance for a consumer’s identity, the more negative consumers respond to embedded tangible (vs. intangible) features, because these consumers perceive a company’s norm violation through internal product upgrades as particular relevant (given their close bond to the product and its features). In contrast, if consumers are required to pay a fee to upgrade a built-in feature in a base product that is less relevant to their self-identity, we do not expect them to show different responses for tangible (vs. intangible) features. These consumers are less attached to the product and its features, and the norm violation becomes less relevant to them; formally:

H5

If the upgraded product is relatively more relevant to consumers’ identity, they will respond less favorably to tangible (vs. intangible) upgrades; if the product is less relevant to consumers’ identity, their responses to tangible (vs. intangible) upgrades will be relatively unaffected.

Design, participants, and procedure

We collected survey data from customers of a global car leasing company. Participating customers have an ongoing contract with the company (i.e., they are in possession of a leased car). We also supplemented the survey data with secondary contract-based data (i.e., gender, age, and monthly net leasing price). We chose the automotive leasing context because it is a prevalent financing model for cars, and independent leasing companies are common in this industry; thus, this context allows us to also investigate potential spillover effects (from the manufacturer to the leasing company). Notably, cars are also relevant to the identity of many consumers (Belk, 1988), which makes it an ideal category for our study. The online survey was administered by the partner company, with a final sample size of 313 customers.Footnote 10

Importantly, we asked customers to think about their own leased car before reading a promotional offer related to our study. Because the focal upgraded feature was a head-up display, participants first indicated whether they already have a head-up display in their leased car. Next, they read a description of the offer for activating the head-up display in their own leased vehicle, which would be available for the duration of the lease (see Web Appendix A). After reading the offer, customers indicated their loyalty intentions and their perceptions of betrayal by the leasing company (for brevity’s sake, analyses on betrayal are presented in Web Appendix E), using the same items as in previous studies but adapted to the car leasing context. Moreover, customers reported their perceived tangibility of the added feature on a four-item scale (Schmitt, 2019; Shostack, 1977); finally, they assessed the product’s relevance for their identity on a four-item scale (Coulter et al., 2003) (see Appendix A).

Results

Loyalty intentions toward the leasing company

We analyzed customers’ loyalty intentions toward the leasing company as a function of feature tangibility perceptions, product identity relevance, and their interaction, controlling for gender, age, head-up display possession, and monthly net leasing rate. The regression analysis showed the expected interaction (b = − 0.096, t = − 3.80, p < 0.001), and main effects of feature tangibility perceptions (b = 0.198, t = 2.17, p < 0.05) and product identity relevance (b = 0.242, t = 2.60, p < 0.01).

We performed a floodlight analysis to explore the significant two-way interaction. The effect of perceived feature tangibility on loyalty intentions was significant among customers whose product identity relevance was higher than 2.94 (b = − 0.084, t = − 1.97, p = 0.05; see Fig. 4). Customers high in product identity relevance (> 2.94) showed less favorable loyalty intentions toward the leasing company when perceiving the internally upgraded feature as relatively tangible (vs. intangible). Loyalty intentions for customers low in product identity relevance (< 2.94) were relatively unaffected by feature tangibility perceptions.Footnote 11

Discussion

Study 5 suggests that offering fee-based access to built-in, tangible product features can elicit negative responses of customers that consider the base product relevant for their identity. Importantly, the negative effect of feature tangibility is attenuated for customers with a low product identity relevance, supporting H5. Moreover, Study 5 shows that consumers’ negative responses to internal product upgrades even hold in a non-ownership leasing context, which is a conservative test for our theory. Additionally, we find that internal product upgrades are not only detrimental to the focal firm. Rather, internal product upgrades can have negative spillover effects for partners of the manufacturer (e.g., leasing companies) akin to ‘guilt-by-association’. Finally, the results of this study also add to the external validity of our research as we (1) surveyed customers of a leasing firm who are periodically surveyed regarding new product ideas (and thus understand that their answers are considered by the firm), and (2) asked them to think about their actual car, which they leased from the firm. Surveying customers with an actual relationship with the firm is also conceptually closer to the contexts studied in prior research on the mediating role of customer-perceived betrayal.

Single paper meta-analysis

We further tested the overall validity of H1 by performing a single paper meta-analysis (SPM; McShane & Böckenholt, 2017) on Studies 1–4. We standardized the dependent variables and only included those conditions (internal vs. external product upgrades), in which the effect was not attenuated by the manipulated moderator condition (i.e., consumer upgrading conditions (Study 2), tangible feature conditions (Study 4)). Since Studies 1, 3A, and 3B contained multiple outcome variables (i.e., WTP and loyalty intentions), we used the outcome variable with weaker results (WTP for Studies 3A, 3B; loyalty intentions for Study 1), for a more conservative test. This test is also conservative as it does not include any control variables. In support of our theory, the SPM showed that across our studies, consumers’ behavioral intentions were significantly lower when they were facing internal (vs. external) product upgrades (Estimate = − 0.3650, SE = 0.0578; z = − 6.31, p < 0.0001).

General discussion

Although manufacturers increasingly transform (traditionally) static physical products into dynamic service platforms that allow consumers to reconfigure them after the purchase, research on this novel phenomenon is scant. Therefore, we examine internal (vs. external) product upgrades to help marketers understand how consumers respond to this new after-sales revenue model. Six studies show that consumers respond less favorably to internal (vs. external) product upgrades. Moreover, we shed light on the underlying process driving this unfavorable response (a serial mediation: internal product upgrades → perceived feature ownership → perceived betrayal → unfavorable consumer intentions). We also examine (1) two boundary conditions related to elements of the managerial marketing mix, and (2) a consumer-related factor that help firms with better managing internal product upgrades.

Theoretical implications

Internal product upgrades elicit negative post-purchase reactions

By investigating internal product upgrades, we respond to Ng and Wakenshaw’s (2017) call for more research on post-purchase product modifications. Internal product upgrades are a promising product modification strategy from both a managerial and scholarly perspective, beyond existing modifications through software (Erat & Bhaskaran, 2012; Yoo et al., 2012) or external product upgrades (Bertini et al., 2009). Yet, we find that this strategy can backfire, as internal (vs. external) product upgrades elicit less favorable consumer responses. Although add-ons are an important after-sales tool, marketing research has mainly focused on consumers’ pre-purchase evaluations of both non-restricted (Bertini et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2015) and restricted features (Wiegand & Imschloss, 2021). We extend research in the post-purchase phase that investigated different forms of non-permanent internal product upgrades without comparing them to established product reconfiguration approaches (Schaefers et al., 2022). By showing that a feature’s locus (i.e., a feature is physically detached from vs. built-into the product) has negative effects for consumers’ WTP and their relationship to the firm, and even related third-party organizations (e.g., car leasing firms), we offer new insights into product upgrades. These insights are important for scholars and managers, because consistent with increasingly service-dominated economies and the servitization of goods (Vargo & Lusch, 2017) we expect that dynamic service platforms will become even more relevant.

Perceived norm violations explain the negative effects of internal product upgrades

Investigating the underlying reasons for the negative effects, our studies show that consumers feel betrayed by a firm’s internal product upgrades. This betrayal arises because consumers believe they already own the built-in feature, even though they do not have any legal claim to this feature’s functionality without paying an extra fee. In this respect, our findings contribute to research on product versioning (Gershoff et al., 2012) by demonstrating that a fee-based activation of restricted functionalities after the product purchase does not heal the negative effects of product versioning; rather, it further undermines consumers’ responses after the product purchase. We extend prior work by showing that consumers perceive being offered fee-based access to a tangible feature in a product they already own as a norm violation.

Perceived feature ownership drives consumers’ betrayal perceptions

By highlighting the relevance of normative standards that consumers apply to purchased products, we enrich prior research on perceived betrayal and psychological ownership in consumer-firm relationships. Answering a call for more research on perceived betrayal, which is in its “infancy” (Reimann et al., 2018, p. 250), our betrayal-ownership framework is crucial for understanding why consumers respond negatively to internal product upgrades. As such, we expand research on perceived betrayal that is often limited to investigations on charities (Joireman et al., 2020) and communication tactics (e.g., Jewell & Barone, 2007).

Moreover, our work offers unique insights into perceived ownership by taking a reversed endowment effect perspective (Kahneman et al., 1990). While research on the endowment effect investigates how much money owners are willing to accept to give up their ownership for a base product (Kahneman et al., 1990), we examine how much money owners of a base product are willing to pay for a feature that is part of a purchased product but is deliberately restricted. We find that higher feature ownership perceptions elicit perceived betrayal and reduce favorable consumer responses (e.g., WTP/purchase intentions and loyalty intentions).

Upgrading responsibility matters

By shifting the upgrading responsibility away from consumers and toward the firm, an important distribution-related strategy, managers can mitigate the negative effects of internal product upgrades, which underscores that firms must carefully design the upgrading process. While Ng and Wakenshaw (2017) emphasize self-customization as a key characteristic of dynamic service platforms, we show that shifting the upgrading responsibility to the firm (and thus making it less obvious that the increased performance is ‘just a fingertip away’ from use) buffers the negative consequences of internal product upgrades. Thus, firms should assess the extent to which they exploit the full potential of IoT-related upgrades, which are likely to make the norm violation more salient.

Feature tangibility matters

Whereas digital and physical products were easy to distinguish in the past, their boundaries are increasingly blurred; thus, Schmitt (2019, p. 825) states: “the digital revolution is entering a new phase […] by incorporating digital information into physical, solid products.” Just like smartphones, everyday physical objects such as cars and TVs are increasingly (pre-)equipped with digital technology, sensors, or services (Kannan & Li, 2017; Yoo et al., 2012). Therefore, our finding that feature tangibility influences post-purchase product modifications is non-trivial, because consumers tend to perceive tangible and intangible products differently (Atasoy & Morewedge, 2017; Belk, 2013). We show that feature tangibility affects the negative effects of internal product upgrades on perceived feature ownership and, in turn, perceived betrayal and loyalty intentions (i.e., the negative effect is attenuated when consumers upgrade an intangible vs. tangible feature). By showing that perceived feature ownership and perceived betrayal are greater for permanent tangible versus intangible internal product upgrades, while they are relatively unaffected for external product upgrades, our results complement research by Schaefers et al. (2022), who focused on monthly subscriptions for internal product upgrades only. Moreover, although research often treats a product’s physical (i.e., tangible) and digital (i.e., intangible) aspects as discrete elements, consumer perceptions of such products might be malleable: they may evaluate a product differently as a function of whether they perceive it to be more tangible or intangible. Therefore, in Study 5, we examined consumers’ perceived feature tangibility, indicating the relevance of our findings for products that entail both tangible (i.e., physical) and intangible (i.e., digital) elements. Study 5 showed that the negative effect of tangible features is only prevalent for customers who perceive the base product (i.e., their car) as highly relevant for their identity, but there was no difference for customers with a low product identity relevance.

Managerial implications

As internal product upgrades are increasingly emerging in the marketplace, firms need to understand how consumers respond to this after-sales revenue model. Our work alerts managers to the notion that internal product upgrades can cause unintended consequences. However, we also identify actionable contextual and consumer-related moderators, which provide useful implications for managers, summarized in Table 3. First, we investigate a distribution-related strategy: although self-service upgrades seem convenient for consumers, having the firm perform the upgrade can mitigate the negative effects (e.g., on WTP and perceived betrayal (Study 2)). Thus, managers may want to offer firm-implemented upgrading instead of consumer/self-service upgrading, at least as long as internal product upgrades are not established as a new normative standard in the marketplace.

Second, we investigated a product strategy related to the tangibility of a given feature. Managers should segment their customers, features, and products, as our findings suggest that internal product upgrades elicit negative responses particularly for tangible (i.e., hardware) features (Study 4). In contrast, when an intangible (i.e., software) feature is upgraded, the negative effect of internal product upgrades is mitigated. On a related note, managers should also consider how relevant a base product (e.g., a car) is for a customer’s identity, as the negative effects for features that are perceived as tangible are attenuated for customers with a low product identity relevance (Study 5). Therefore, companies should track customers’ perceived feature tangibility and their product identity relevance (e.g., as part of their market research) (Coulter et al., 2003; Leung et al., 2019). Managers can leverage these insights twofold: First, they can segment customers based on their feature tangibility perceptions as well as their product identity relevance and then target those customers who perceive the added feature as rather intangible or in case of features that are perceived as rather tangible have a low product identity relevance.Footnote 12 Second, firms can segment features and base products for which they provide internal product upgrades and focus on features that are intangible or offer them only for products that are less relevant to a customer’s identity.

Third, demonstrating the robustness of our core effect, we show that negative effects of internal product upgrades even emerge in a non-ownership context (i.e., car leasing, Study 5). Importantly, this finding shows that internal product upgrades can cause spillover effects for third-party business partners, like leasing companies. Accordingly, companies that offer product leasing should cautiously balance the pros and cons of internal product upgrades.

Fourth, we not only identify managerially relevant moderators that help alleviate the risks of internal product upgrades, but also include studies that test different promotional strategies (i.e., [a] leveraging transparency at the pre-purchase stage, [b] emphasizing convenience benefits of the upgrade, and [c] using norm appeals). These studies, which are reported in Web Appendices F and G, show the robustness of the basic effect and seem to suggest that the focal strategies were not effective in reducing the negative effects of internal product upgrades, but we note that other promotional messages might be more effective and more research is therefore needed.

Limitations and future research

Our work has limitations that provide promising directions for future research (Table 4). First, we focus on the post-purchase phase, but product modifications can also affect consumers’ pre-purchase evaluations of a base product (Gershoff et al., 2012). Extending findings of Wiegand and Imschloss (2021), future research could examine how internal product upgrades influence, for instance, the number of features selected by consumers. Second, further research might identify additional strategies that prevent negative consumer responses. For example, could anthropomorphizing the product or the added feature prevent a negative response? Third, in Study 4, we manipulated feature tangibility using two features (i.e., one being rather tangible, while the other was rather intangible in nature). Future research might investigate whether manipulating feature tangibility using promotional appeals can also mitigate the negative effects. Fourth, Study 5 surveyed actual customers of a leasing company, but we used a scenario-based approach because access to real-world data for fully implemented internal product upgrades is still limited. As this new after-sales revenue model becomes more prevalent, researchers will gain access to real-world data that would, for example, allow tracking the effects of internal product upgrades over time. Also related to Study 5, we controlled for head-up display possessions by asking consumers whether they had a head-up display in their current leased car. Future research could enrich these data by using secondary data and controlling for the car model features. Fifth, the ethical aspects of internal product upgrades also require attention. While internal product upgrades promise revenues and cost savings for firms, this approach raises questions of environmental sustainability. On the one hand, a-priori embedding hardware (e.g., microchips, batteries) into products that consumers might not use can be detrimental for the environment (e.g., the more sensors and other hardware a car includes, the more energy and fuel it typically needs). On the other hand, internal product upgrades may have the potential to extend product lifecycles, as consumers can modify their products. Moreover, modified products might present opportunities for markets of pre-owned products, which seems favorable for the environment. In short, there might be beneficial and harmful aspects of internal product upgrades for the environment that should be investigated. Finally, the research area on internal product upgrades and the related terminology is still nascent and evolving. On a conceptual level, future research could synthesize knowledge on related product reconfiguration phenomena that use different terminologies (e.g., internal product upgrades, OTA updates, on-demand features).

Notes

For instance, Tesla’s 60 kWh vehicles were originally equipped with a 75 kWh battery that was deliberately restricted in its functionality via software by the company. Customers who owned the 60 kWh vehicle had the option to pay an extra fee of $2,000 to unlock the additional 15 kWh capacity after purchasing the vehicle.

Product reconfiguration refers to the fact that a product’s functionalities can be expanded after the product is purchased. Thus, product reconfiguration is hereafter referred to as post-purchase product modification.

Existing studies on OTA updates investigate operational aspects (e.g., Bauwens et al., 2020) or focus on consumer reactions to software feature updates that are continuously developed (e.g., Foerderer and Heinzl 2017; Franzmann et al., 2019a, 2019b), but they do not examine fee-based upgrades of built-in features that are theoretically fully usable, which is a key characteristic of internal product upgrades.

We further enhance the scholarly and managerial relevance of our research through additional studies (Web Appendix F and G) that test potentially relevant moderators related to promotional strategies. However, these studies find the focal strategies to be non-effective in mitigating negative effects of internal product upgrades.

Although we focus on exchange relationships, we note that communal norms can also influence commercial relationships. However, even in these relationships, the commercial elements dictate a certain level of quid pro quo, especially because relationships with firms almost always involve monetary payment (Aggarwal 2004). For instance, even though healthcare providers are often described through a communal lens, their services are linked to payment (and the vast majority of healthcare providers will not provide services without payment).

In all instances where WTP is included, we log-transformed this variable. In line with prior literature (e.g., Zhou et al., 2018), we log-transformed the data after adding 1 to each score to include zero values.

We control for gender and age across all studies (e.g., Gilly and Zeithaml 1985; Lee and Coughlin 2015), as these variables can affect the contexts we study. We note that our hypothesized effects are stable when control variables are included or excluded (Web Appendix B); Web Appendix C shows results for the control variables.

That is, one alternative explanation for the observed effects is that participants consider internal product upgrades as less effortful for companies. Following a cost-plus pricing approach (Kalapurakal et al., 1991), consumers might expect reduced prices due to lower costs/effort for companies. A second alternative is that consumers are concerned with the environmental impact of internal product upgrades. Integrating additional hardware features into products by default may seem wasteful from a sustainability point of view (e.g., Arkes 1996), which could explain a less favorable response to such upgrades. We thank reviewers for pointing to these alternative explanations. Please see Web Appendix D for detailed results of these alternative explanations.

In addition to WTP, we assessed consumers’ purchase intentions of the product upgrade using a four-item measure (Chandran & Morwitz, 2005). Consistent with the results for WTP, an ANCOVA on purchase intentions found that consumers were significantly less likely to purchase the internal (vs. external) upgrade (Minternal = 3.48 vs. Mexternal = 4.36; F(1, 268) = 12.47, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04). We find a significant serial mediation on purchase intentions (internal product upgrade → higher feature ownership perceptions → increased perceived betrayal → reduced purchase intentions); a × b = − 0.0336, 95% CI = [− 0.0816, − 0.0055].

A total of 2,300 survey invitations were delivered to the firm’s customers during the 24-day collection period. Of those invited, 399 responded (17.3%). Of the 399 responses, 86 (21.6%) were incomplete, resulting in 313 customers (Mage = 48.26, 20.4% female).

The correlations of the relationships of the model (range: 0.02–0.34) and the variance inflation factors (range: 1.00–1.07) indicate that multicollinearity is not an issue (Mason & Perreault Jr., 1991).

Proactively targeting these consumers (with a low product identity relevance) seems especially important, as long as internal product upgrades have not become standard practice. As our conceptual focus on marketplace norms suggests, consumers might get used to internal product upgrades over time; at that point, firms might be able to promote internal product upgrades to all their customers, regardless of product identity relevance.

In Study 5, the items were adapted to replace the word “buy” with “lease” for the leasing firm’s customers.

In Study 4 we manipulated feature tangibility; the manipulation check was “a digital product/a physical product”.

References

Aggarwal, P. (2004). The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 87–101.

Aggarwal, P., & Zhang, M. (2006). The moderating effect of relationship norm salience on consumers’ loss aversion. Journal of Consumer Research, 33, 413–419.

Arkes, H. R. (1996). The psychology of waste. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 9, 213–224.