Abstract

We explore how first-time adopters of complex new technology products are influenced by the volume of positive WOM that they receive prior to adoption. Such positive WOM can flow through to alter adopter’s goals during initial product use, with consequences for their usage experiences and strategies. Two longitudinal surveys and an experiment reveal a potential downside of positive WOM. Specifically, receiving a greater volume of positive WOM about a new technology product can establish normative standards for adopter’s performance during product use. This leads adopters to feel pressure to meet those standards, prompting avoidance-oriented performance goals for initial use of their new product. Together, these processes undermine adopter’s experiences with their new product, as well as their strategies for using it. Our findings offer insights for marketers and researchers by identifying and explaining an ironic post-adoption effect of PWOM.

Too much of a good thing? High volumes of positive WOM can undermine adopters of new technology products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Introducing new products is critical for companies but fraught with challenges. When consumers consider complex new technology products, uncertainty about the product’s potential benefits and costs can undermine their willingness to adopt (Hoeffler, 2003). The effort and challenge of learning to use such products increases the risk of failing to realize their potential benefits (Alexander et al., 2008; Rogers, 2003). Exacerbating these challenges, the adoption decision is not the end of the process. Post-adoption, Rogers (2003) identifies the implementation stage, where adopters begin to use the product. Here, they must make the behavioral changes needed to gain its benefits; failure to attain these benefits could result in disadoption (Lehmann & Parker, 2017; Parthasarathy & Lassar, 2023).

As they prepare for initial new product use, adopters form achievement goals which may be mastery goals or performance goals. Mastery goals aim to attain competence relative to intrapersonal or absolute standards, while performance goals aim to attain competence relative to interpersonal or normative standards (Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). Performance goals can be approach- or avoidance-oriented, toward gaining positive—or avoiding negative—judgments of competence from others (Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Elliott, 1983; Elliot, 1999). Critically, the goals that new product adopters pursue during initial product use influence how they interpret, evaluate, and act on achievement information and task feedback during that use (Ames & Archer, 1987; Dweck, 1986).

Prior research on new products has largely focused on the impact of mastery goals. For example, reference-group comparisons can affect adopter’s expectations about their potential to achieve mastery with skill-based products (Harding et al., 2019). Similarly, product (dis)satisfaction is driven by the extent to which early experiences (dis)confirm adopter’s expectations about whether they can achieve mastery (e.g., Parthasarathy & Bhattacherjee, 1998). We focus instead on performance goals.

We do so because innovation diffusion is an interpersonal process. Individuals receive a great deal of information from other consumers, which can influence new product adoption or rejection (Rogers, 2003). Such word-of-mouth (WOM) is a vital process in the marketplace (Moore & Lafreniere, 2020), especially for the success of new products (Baker & Naveen, 2018). WOM is a critical driver of sales (Babić Rosario et al., 2016), yet its potential to have an impact post-adoption—during initial new product use—has been underexplored. This research contributes by exploring how the volume of positive WOM (PWOM) that first-time adopters receive about new technology products affects their performance goals, and therefore their experiences during initial product use.

In two longitudinal surveys and an experiment, we reveal an ironic post-adoption effect of PWOM, and explore why this effect occurs. We find that receiving greater volumes of PWOM prior to adopting a new technology product can establish descriptive social norms for people’s product performance during initial use. Adopters feel pressure to meet these normative standards and avoid negative judgments from others, so they pursue avoidance-oriented performance goals (Elliot, 1999; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). Ultimately, these processes negatively impact adopter’s experiences with their new product, as well as their strategies for using it.

Below, we outline our predictions, present our empirical work, and discuss its implications for researchers and marketers.

2 Conceptual development

2.1 Performance goals

We focus on consumer’s performance goals during initial product use. These goals, which focus on attaining competence relative to normative standards, can be approach- or avoidance-oriented, and are reflected in the emotions adopters experience as they begin using their new product (Elliot, 1999). When adopters pursue performance-approach goals, they focus on the benefits and potential of the new product and are motivated to achieve success relative to normative (i.e., descriptive) standards. As a result, when learning about and using their new product, they experience positive emotions such as excitement (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996). In contrast, when adopters pursue performance-avoidance goals, they focus on the costs and challenges of the new product and are motivated to avoid failure relative to normative standards. As a result, when learning about and using their new product, they experience negative emotions such as anxiety (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996). Accordingly, we conceptualize and measure positive and negative emotions as indicators of performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals, respectively.

Although performance goals strongly influence adopter’s new product experiences (Ames & Archer, 1987), little work has examined what factors might prompt adopters to pursue approach- or avoidance-oriented performance goals. We identify and explore one possible factor: the volume of PWOM that adopters receive.

2.2 Positive word-of-mouth

PWOM generally has positive effects on consumers: it improves product attitudes, reduces perceived risk, encourages trial and adoption, and increases sales (Babić Rosario et al., 2016; Moore & Lafreniere, 2020). PWOM can help consumers decide whether to adopt a new product by providing positive information about its benefits and attributes; thus, PWOM may prompt performance-approach goals.

At the same time, PWOM can inform adopters about the challenges of learning and using a new product—especially new technology products (Rogers, 2003). Further, PWOM can set expectations about normative standards of performance with a new product, against which adopters may be judged (Rogers, 2003). To positively evaluate and recommend a new product (e.g., “This app is awesome!”), consumers must have gained competence with it. In other words, PWOM sets standards about others’ success and competence with the product.

Critically, we posit that performance goals will increase as adopters receive more PWOM. Higher volumes of PWOM indicate greater consensus about the quality and benefits of the product (He & Bond, 2015; Moore & Lafreniere, 2020). This should strengthen performance-approach goals. Simultaneously, however, higher volumes of PWOM indicate stronger social norms and higher performance standards (Gerard et al., 1968; Latané & Wolf, 1981). As volume increases—as more and more others endorse the product—failure to meet these standards reflects more negatively on the individual (not the product; Moore & Lafreniere, 2020). This should strengthen performance-avoidance goals. Because this latter effect is novel and ironic, our subsequent theorizing and empirics explore the relationship between PWOM volume and performance-avoidance goals.

2.3 Pressure to perform & product complexity

We posit that the link between PWOM volume and performance-avoidance goals is mediated by pressure to perform and moderated by product complexity.

First, as greater volumes of PWOM strengthen normative standards of performance, adopters who fail to meet these standards become increasingly likely to be judged negatively on their competence. In response, we suggest that adopters feel pressure to perform at least as competently as those sharing PWOM. Stated differently, adopters feel they should meet the normative performance standards set by PWOM; this felt pressure should increase as PWOM volume increases. An inability to meet these performance standards could result in negative judgments from the self and others (Smith, 2000). Adopters should be motivated to avoid such undesirable outcomes, in turn prompting performance-avoidance goals (Elliot, 1999).

Second, the link between PWOM volume and pressure to perform may be especially strong for complex new technology products (Rogers, 2003). Although more-complex products are more difficult to understand and use, receiving high volumes of PWOM about these products suggests that others have gained competence with them, despite their complexity. As a result, the pressure to perform that adopters feel with increasing PWOM volume should be stronger for complex products. In short, product complexity should moderate the relationship between PWOM volume and pressure to perform.

2.4 Consequences for new product use

Taken together, we expect PWOM volume, pressure to perform, and performance-avoidance goals to have consequences for adopters during initial new product use. We focus on product experiences and usage strategies.

First, performance-avoidance goals influence adopter’s interpretation and evaluation of achievement information and task feedback during initial product use, making negative experiences and outcomes more salient (Ames & Archer, 1987; Dweck, 1986). As a result, adopters with performance-avoidance goals may exhibit outcomes such as greater dissatisfaction, ongoing negative emotion, and negative usage surprises.

Second, performance-avoidance goals should lead to more conservative usage strategies, such as spending more time reading instructions and engaging in more constrained product exploration. These strategies undermine the insight-based learning associated with positive usage outcomes (Lakshmanan & Krishnan, 2011).

2.5 Conceptual model

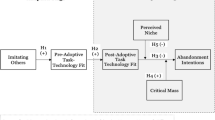

Figure 1 presents our conceptual model. We predict that greater volumes of PWOM will prompt performance-avoidance goals—reflected in negative emotions—via pressure to perform. Product complexity will moderate the effect of PWOM volume on pressure to perform. Overall, this process will lead adopters to have more negative usage experiences and to use their new products more conservatively.

3 Overview of studies

In two surveys and an experiment, we explore how PWOM volume affects first-time adopters of complex new technology products.

Studies 1 and 2 are longitudinal surveys of consumers adopting new communications and entertainment products. During Wave 1 of these surveys, we contact consumers who have decided to adopt a new product for the first time, but who have not yet acquired it. We measure the volume of PWOM they heard about the product, along with performance-avoidance goals, pressure to perform (Study 2 only), and usage intentions for the new product. During Wave 2, we contact Wave 1 respondents who have received and used the product and measure their actual initial usage experiences and strategies. We then explore whether PWOM volume affects initial usage outcomes via pressure to perform (Study 2) and performance-avoidance goals (Studies 1 and 2). Study 3 is a scenario-based experiment about adopting a 3D printer for use in the kitchen. We manipulate PWOM volume and measure perceptions of product complexity. This study replicates our surveys while offering support for the moderating effect of product complexity.

Table 1 includes sample items from each study; the Supplemental Appendix includes all measures across studies. For brevity, we report only measures and analyses that are relevant to our hypotheses; additional details and analyses are available in the Supplemental Appendix and from the authors.

4 Study 1

Study 1 offers a first examination of our prediction that receiving greater volumes of PWOM can indirectly, negatively affect adopter’s initial product usage experiences and strategies by prompting performance-avoidance goals.

4.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from the CBS Television City online panel in 2004. We identified consumers who planned to acquire one of 21 communications or entertainment products for the first time in the next 2 months (Table 2).

Eligible consumers agreed to be surveyed one week before product acquisition (Wave 1), 1–2 weeks after acquisition (Wave 2), and six weeks after acquisition (Wave 3). We report relevant data from Waves 1 and 2 (the number of responses in Wave 3 was insufficient for analysis). Our analyses utilize responses from the final sample of 299 participants who completed both waves (51% female; Mage = 35.96, SD = 9.82). Participants in Wave 1 who did (vs. did not) complete Wave 2 did not differ on key measures.

4.2 Surveys

In Wave 1, prior to product acquisition, participants reported on: perceived PWOM volume (I heard many people talking about how [product] has many advantages and benefits; 1 = strongly disagree/5 = strongly agree); performance-avoidance goals (anxious and worried; 1 = strongly disagree/5 = strongly agree); intended conservative usage strategies (hours spent reading instructions; percent of features used)Footnote 1; and being an early adopter. The early adopter measure is used as a covariate in our analysis (Rogers, 2003).

Participants qualified for Wave 2 if they had acquired the product and had it available for use in the previous 7–21 days. During Wave 2, they reported on actual conservative usage strategies during the first week they had the product, using the items from Wave 1. Then they reported on negative usage experiences (negative surprises, ongoing negative emotions; 5-point agree/disagree scales) during initial product use.

4.3 Results

First, we examined the relationship between PWOM volume and performance-avoidance goals. As expected, greater PWOM volume was associated with increased performance-avoidance goals (b = 0.14, t(296) = 2.18 p = .03).

Second, we tested the relationship between performance-avoidance goals and usage experiences (Wave 2) and intended (Wave 1) and actual (Wave 2) conservative usage strategies. Performance-avoidance goals were associated with increased negative usage experiences (b = 0.45, t(296) = 10.53, p < .001), intended conservative usage (b = 0.28, t(293) = 3.44, p < .001), and actual conservative usage (b = 0.51, t(295) = 6.74, p < .001).

Finally, we tested whether PWOM volume indirectly affected these outcomes. Mediation analyses (Hayes, 2017; model 4; 10,000 bootstrap samples) showed significant indirect effects of PWOM volume on negative usage experiences (CI95: 0.01–0.14), intended conservative usage (CI95: 0.01–0.11), and actual conservative usage (CI95: 0.01–0.18) via performance-avoidance goals.

4.4 Discussion

Study 1 offers initial evidence that greater volumes of pre-acquisition PWOM are indirectly and negatively related to adopter’s subsequent experiences and usage strategies with their new products. This occurs because adopters who receive more PWOM form more performance-avoidance goals. In turn, performance-avoidance goals lead to more negative usage experiences and more conservative usage strategies. These effects were shown in usage intentions before product acquisition and in initial use shortly after acquisition.

5 Study 2

Study 2 aims to replicate and extend Study 1. Using another longitudinal survey of first-time adopters of new technology products, we again test the predicted relationships between PWOM volume, performance-avoidance goals, and new product usage experiences and strategies. Further, we test the proposed mediating role of pressure to perform and measure a broader range of usage experiences.

5.1 Participants

Via Qualtrics, in 2016, we recruited consumers who intended to acquire one of 19 communication or entertainment products for the first time in the next 1–2 weeks (Table 2), and who agreed to be surveyed prior to acquisition (Wave 1) and one week after acquisition (Wave 2). For analyses that require only Wave 1 data, we used 505 total responses from Wave 1 participants (64% female, Mage = 35.69, SD = 11.08). For analyses requiring Waves 1 and 2, we used responses from 140 participants who completed both waves (61% female, Mage = 33.90, SD = 10.43). Participants in Wave 1 who did (vs. did not) complete Wave 2 did not differ on key measures.

5.2 Surveys

In Wave 1, participants reported on performance-avoidance goals, pressure to perform, intended usage strategies, and perceived PWOM volume, similar to Study 1 (1 = strongly disagree/7 = strongly agree). We measured early adopter tendencies and perceived product newness as covariates (Rogers, 2003).

To be eligible for Wave 2, participants had to have been using the product for at least seven days (those who did not qualify yet were re-contacted later). In Wave 2, participants reported on four initial usage experiences (7-point agree/disagree scales): product dissatisfaction, negative usage surprises, disconfirmation of expectations, and intentions to spread NWOM. Participants then rated their ongoing negative emotions while using the product in the coming week. Participants also reported on actual conservative usage strategies as in Study 1.

5.3 Results

We first tested the predicted relationships between PWOM volume, pressure to perform, and performance-avoidance goals. As expected, greater PWOM volume was associated with increased pressure to perform (b = 0.21, t(501) = 3.54, p < .001), and pressure to perform was associated with increased performance-avoidance goals (b = 0.18, t(501) = 5.57, p < .001). Mediation confirmed that PWOM volume increased performance-avoidance goals via pressure to perform (CI95: 0.02–0.07; model 4).

Next, we examined the relationship between performance-avoidance goals and usage experiences. Performance-avoidance goals were associated with increased dissatisfaction (b = 0.21, t(136) = 2.87, p < .01), negative usage surprises (b = 0.37, t(136) = 3.44, p < .001), disconfirmed expectations (b = 0.35, t(136) = 3.62, p < .001), NWOM intentions (b = 0.27, t(136) = 2.72, p < .01), and ongoing negative emotion (b = 0.52, t(136) = 8.16, p < .001). A serial mediation analysis showed that PWOM volume indirectly increased dissatisfaction (CI95: 0.0001–0.03), negative usage surprises (CI95: 0.0002–0.05), disconfirmed expectations (CI95: 0.00–0.04), NWOM intentions (CI95: 0.00–0.04), and ongoing negative emotion (CI94: 0.00–0.05) via pressure to perform and performance-avoidance goals (model 6).

Finally, we tested the relationship between performance-avoidance goals and intended and actual conservative usage strategies. Performance-avoidance goals were associated with increased intended conservative use (b = 0.13, t(501) = 2.63, p < .001). A serial mediation analysis showed that PWOM volume increased intended conservative use via pressure to perform and performance-avoidance goals (CI95: 0.0003–0.01; model 6). Unexpectedly, performance-avoidance goals were not associated with actual conservative use (p > .48). Further, there was no indirect effect of PWOM volume on actual conservative use via pressure to perform and performance-avoidance goals (CI95: -0.01–0.003; model 6).

5.4 Discussion

This second longitudinal survey offers additional evidence that PWOM volume can negatively affect adopters. We found that greater perceived PWOM volume increased the pressure first-time adopters felt to use their new technology product competently. This pressure elicited performance-avoidance goals, which undermined adopter’s intended usage strategies and initial usage experiences. Together, across different time periods and different sets of technology products, Studies 1 and 2 reveal the predicted relationships between PWOM volume, pressure to perform, performance-avoidance goals, and new product usage experiences and strategies.

6 Study 3

Study 3 builds on our survey findings with an experiment that manipulates PWOM volume and tests the moderating effect of product complexity. Study 3 also explores whether the effect of PWOM volume on pressure to perform depends on PWOM content that cues recipients to consider the product’s learning costs and risks.

Participants read a scenario about a really-new product (i.e., one with which consumers lack prior experience; Hoeffler, 2003): a 3D printer for the kitchen. In the scenario, participants receive low or high volumes of PWOM, which either strongly or weakly cues learning costs and risks. We measure pressure to perform, performance-avoidance goals, expected usage experiences and strategies, and perceived product complexity.

Study 3 aims to replicate our previous findings that increasing PWOM volume indirectly undermines adopter’s initial usage experiences and strategies via pressure to perform and performance-avoidance goals. It also tests whether the relationship between PWOM volume and pressure is moderated by product complexity, and whether these relationships hold regardless of whether PWOM cues learning costs and risks.

6.1 Design and methods

We pre-screened Mechanical Turk participants (N = 1428) using a “Consumer Preferences & Hobbies” survey. Those who knew what a 3D printer was and who were interested in baking qualified (N = 630). Qualified participants were invited to complete Study 3 (N = 461; 63% female; Mage = 40.06, SD = 12.00), a 2 (PWOM volume: high, low) by 2 (cuing learning costs: strong, weak) between-subjects study.

Participants read an introductory paragraph describing 3D printers and how they can be used for creating desserts in the kitchen. Next, they read a scenario where they received PWOM about a 3D printer during a dinner prepared by a friend, along with other guests. The friend gushes about the 3D printer, reinforcing PWOM the participant had heard previously from the friend (low PWOM volume) or from many friends (high PWOM volume). The friend describes what they have done with the printer, shows its use, and points out its technical aspects.

The scenario also manipulated the degree to which PWOM cued learning costs and risks. In the weak-cue condition, participants read that using the printer is straightforward, they should be able produce great treats, and they should invite others over and share. In the strong-cue condition, participants read that using the printer is not the easiest thing to do, that they could produce some embarrassing monsters, and they should wow others and share their designs. Stimuli are in the Supplemental Appendix.

After reading the scenario, participants imagined they had acquired and set up the 3D printer and were asked to think about how they would use it for the first time. Then, like prior studies, participants reported on performance-avoidance goals, pressure to perform, early adopter tendencies (covariate), intended conservative usage strategies, and four anticipated usage experiences: negative surprises, dissatisfaction, disconfirmed expectations, and intentions to spread PWOM. New in Study 3, we measured product complexity using perceptions of how extreme the product’s benefits were (7-point scales; Hoeffler, 2003).

6.2 Results

First, we tested the relationship between PWOM volume (high = 1/low = -1) and pressure to perform, with mean-centered perceived product complexity and cuing (strong/weak) as moderators. We found a 2-way interaction between product complexity and PWOM volume, such that greater complexity strengthened the effect of PWOM volume on pressure to perform (b = 0.19, t(452) = 2.04, p < .05). Neither the 2-way interaction of PWOM volume and cuing (p > .93) nor the 3-way interaction of PWOM volume, cuing, and complexity were significant (p > .41). Cuing had an independent effect on pressure to perform (see Supplemental Appendix).

Next, we found that greater pressure to perform increased performance-avoidance goals (t(448) = 0.27, p < .001). Mediation analysis showed that PWOM volume indirectly increased performance-avoidance goals via pressure to perform, and this was moderated by product complexity (index of moderated mediation CI95: 0.01 – 0.09; model 7).

We then tested the impact of performance-avoidance goals on usage strategies and experiences. Performance-avoidance goals increased intended conservative usage strategies (b = 0.09, t(458) = 2.39, p < .02) and anticipated negative usage surprises (b = 0.24, t(458) = 6.16, p < .001). Moderated serial mediation analysis (model 83) confirmed that PWOM volume increased intended conservative usage strategies (CI95: 0.001 – 0.01) and negative surprises (CI95: 0.001 – 0.02) via pressure to perform and performance-avoidance goals. Product complexity moderated this relationship, such that greater complexity increased the observed effects.

We found no significant effects for the other anticipated usage experiences (dissatisfaction, disconfirmed expectations, PWOM). See the Supplementary Appendix for results and discussion.

6.3 Discussion

Study 3 provides experimental evidence that receiving a greater volume of PWOM can negatively affect adopters. Using a scenario for a really-new product, we manipulate the volume of PWOM that adopters receive and the degree to which the PWOM cues the product’s learning costs and risks. We also measure product complexity. We find that regardless of whether PWOM cues learning costs and risks, a high (vs. low) volume of PWOM increases adopters’ performance-avoidance goals by increasing pressure to perform with the product. Similarly, via pressure to perform and performance-avoidance goals, PWOM volume undermines adopter’s intended usage strategies and some anticipated usage experiences. These effects strengthen with greater product complexity, as shown in Fig. 2.

7 General discussion

This paper provides an initial exploration of how PWOM volume impacts first-time adopters of new technology products. We show that greater volumes of pre-acquisition PWOM can flow through to alter adopter’s goals for and experiences during initial product use. Specifically, greater PWOM volume can exert pressure for adopters to perform to the normative standards set by PWOM, leading them to form performance-avoidance goals for initial use of their new product. This process undermines adopter’s usage experiences, as well as their intended and actual usage strategies, especially for more complex products.

These findings offer theoretical and practical contributions. On the theory side, we illustrate that PWOM can exert (ironic) post-acquisition effects: while it can positively impact decisions to adopt a complex new technology product, it may subsequently undermine product use. Further, this research suggests that success and satisfaction during new product use are not simply a function of mastery goals and individual expectations (cf., Parthasarathy & Bhattacherjee, 1998). We highlight the importance of performance goals, showing that PWOM can exert pressure to perform and motivate adopters to pursue performance-avoidance goals. In doing so, we contribute more broadly to literature on goal pursuit and social referents. For example, Huang (2018) demonstrates that consumers in the midst of pursuing goals (e.g., losing weight) avoid information about others’ performance, even though this information would be motivating. We show that at the beginning of goal pursuit (e.g., gaining competence with a new product), adopters might be better off avoiding social information.

Practically, this research highlights the importance of managing consumer’s experiences as they transition from adopting to using their new product. Our results suggest that minimizing the potential for adopters to form performance-avoidance goals is as important as conveying the product’s benefits, particularly for complex products. Managing adopter’s propensity to form avoidance- or approach-oriented goals as they begin using their new product is critical because our results hint at a self-fulfilling prophecy. Since adopters with performance-avoidance goals focus on avoiding failure, they exhibit more conservative usage strategies, limiting their opportunities for insights and jumps in learning (Lakshmanan & Krishnan, 2011). Further, their focus on negative usage experiences reinforces their avoidance goals and undermines subsequent product use. These negative outcomes suggest that marketers should attempt to lessen the pressure to perform that adopters bring to their initial product use. To do so, they could shield recent adopters from receiving information about others’ performance. For example, rather than promoting “user success stories” as learning resources, marketers could find ways to show the value of exploration as a path to achieving successful outcomes.

Future research could identify other situational factors (beyond PWOM volume) that lead to different goals and outcomes for adopters. For example, characteristics that speed (slow) the rate of adoption of an innovation (e.g., observability; Rogers, 2003) may decrease (increase) adopter’s performance-avoidance goals. Additionally, future work could explore when PWOM is more or less likely to trigger approach- or avoidance-oriented goals. While adopters in our studies were all close to adopting (i.e., within a week), the time between deciding to adopt and acquiring the new product might play a role. Adopters who are further from acquisition tend to focus on benefits (Alexander et al., 2008)—thus, PWOM may be more likely to elicit excitement (vs. anxiety) when acquisition is further in the future. Future research could also test whether approach- and avoidance-oriented goals do lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, as suggested above. Such work could test interventions that would help avoidance-focused adopters use—and enjoy—their new products.

Data availability

To adhere to the data policy, we have deposited the data here: https://researchbox.org/1606.

Notes

We developed formative indexes of conservative usage strategies (Shih & Venkatesh, 2004); details are in the Supplementary Appendix.

References

Alexander, D. L., Lynch Jr., J. G., & Wang, Q. (2008). As time goes by: Do cold feet follow warm intentions for really new versus incrementally new products? Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 307–319.

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1987). Mothers’ beliefs about the role of ability and effort in school learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 409–414.

Babić Rosario, A., Sotgiu, F., De Valck, K., & Bijmolt, T. H. (2016). The effect of electronic word of mouth on sales: A meta-analytic review of platform, product, and metric factors. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(3), 297–318.

Baker, A. M., & Naveen, N. (2018). Word-of-mouth processes in marketing new products: recent research and future opportunities. Handbook of research on new product development, 313–335.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Elliott, E. S. (1983). Achievement motivation. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 643–691). Wiley.

Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist, 34(3), 169–189.

Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 461–475.

Gerard, H. B., Wilhelmy, R. A., & Conolley, E. S. (1968). Conformity and group size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(1), 79–82.

Harding, R. D., Hildebrand, D., Kramer, T., & Lasaleta, J. D. (2019). The impact of acquisition mode on expected speed of product mastery and subsequent consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(1), 140–158.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

He, S. X., & Bond, S. D. (2015). Why is the crowd divided? Attribution for dispersion in online word of mouth. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1509–1527.

Hoeffler, S. (2003). Measuring preferences for really new products. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(4), 406–420.

Huang, S. C. (2018). Social information avoidance: When, why, and how it is costly in goal pursuit. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(3), 382–395.

Lakshmanan, A., & Krishnan, H. S. (2011). The Aha! Experience: Insight and discontinuous learning in product usage. Journal of Marketing, 75(6), 105–123.

Latané, B., & Wolf, S. (1981). The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychological Review, 88(5), 438–453.

Lehmann, D. R., & Parker, J. R. (2017). Disadoption AMS Review, 7(1), 36–51.

Mahajan, V., Muller, E., & Bass, F. M. (1990). New Product Diffusion models in marketing: A review and directions for Research. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 1–26.

Moldovan, S., Goldenberg, J., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2011). The different roles of product originality and usefulness in Generating Word-of-mouth. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 28(2), 109–119.

Moore, S. G., & Lafreniere, K. C. (2020). How online word-of‐mouth impacts receivers. Consumer Psychology Review, 3(1), 34–59.

Parthasarathy, M., & Bhattacherjee, A. (1998). Understanding post-adoption behavior in the context of online services. Information Systems Research, 9(4), 362–379.

Parthasarathy, M., & Lassar, W. (2023). The adoption and disadoption of electric vehicles by innovators. Marketing Letters, 34(4), 549–573.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free.

Shih, C-F., & Venkatesh, A. (2004). Beyond adoption: Development and application of a Use-Diffusion Model. Journal of Marketing, 68(January), 59–72.

Smith, R. H. (2000). Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons. In J. Suls, & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of Social Comparison (pp. 173–200). Springer.

Urdan, T., & Kaplan, A. (2020). The origins, evolution, and future directions of achievement goal theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101862.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Marketing Science Institute and CBS Corporation for financial support of this research, and Ted Kneisler, David Poltrack, and Brian Rodriguez for their help in fielding Study 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All data collection processes complied with the ethical standards and all participants consented to participate in our studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alexander, D.L., Moore, S.G. Too much of a good thing? High volumes of positive WOM can undermine adopters of new technology products. Mark Lett (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-024-09734-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-024-09734-6