Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence and clinical significance of weight regain after bariatric surgery remains largely unclear due to the lack of a standardized definition of significant weight regain. The development of a clinically relevant definition of weight regain requires a better understanding of its clinical significance.

Objectives

To assess rates of weight regain 5 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG), applying six definitions and investigating their association with clinical outcomes.

Methods

Patients were followed up until 5 years after surgery and weight regain was calculated. Regression techniques were used to assess the association of weight regain with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and the presence of comorbidities.

Results

A total of 868 patients participated in the study, with a mean age of 46.6 (± 10.4) years, of which 79% were female. The average preoperative BMI was 44.8 (± 5.9) kg/m2 and the total maximum weight loss was 32% (± 8%). Eighty-seven percent experienced any regain. Significant weight regain rates ranged from 16 to 37% depending on the definition. Three weight regain definitions were associated with deterioration in physical HRQoL (p < 0.05), while associations between definitions of weight regain and the presence of comorbidities 5 years after surgery were not significant.

Conclusion

These results indicate that identifying one single categorical definition of clinically significant weight regain is difficult. Additional research into the clinical significance of weight regain is needed to inform the development of a standardized definition that includes all dimensions of surgery success: weight, HRQoL, and comorbidity remission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to generally excellent results in terms of weight loss, improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and reduction in overall mortality and morbidity, bariatric surgery is considered the best treatment option for extreme obesity [1, 2]. However, in the long-term, these results are not maintained in all patients. There is growing recognition that weight regain is a concern after bariatric surgery [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Weight regain has been associated with deterioration in HRQoL, the re-emergence of type 2 diabetes and other comorbidities, and patients’ opinion about surgery success [3, 4, 9,10,11].

The key studies focusing on long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery show that patients generally regain 5 to 10% of their total weight loss (%TWL) within the first decade [2, 6, 12]. In the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study, the first large, long-term prospective study, %TWL decreased from 32 to 25% within 10 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [2]. In the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) study, %TWL decreased from 35 to 28% within 7 years after RYGB, and in another large long-term study with a high follow-up rate (90% up to 12 years), %TWL decreased from 35 to 27% within 12 years after RYGB [6, 12]. Thus, it seems that some weight regain after bariatric surgery is common. However, different weight loss trajectories were observed and a subgroup of patients regains a significant amount of weight and experiences associated problems [12].

Estimates of the percentage of patients who regain a significant amount of weight vary widely [4,5,6,7,8]. In a systematic review among 16 studies, weight regain rates ranged from 19 to 87% for patients who underwent RYGB and sleeve gastrectomy (SG), while a systematic review among 21 studies found weight regain rates after SG ranged from 6 to 76% over variable follow-up periods ranging from 2 to 6 years [4, 5]. Both reviews report great variability in assessment methods of weight regain among the included studies. This wide variation arises from the lack of consensus on the definition of weight regain. Many different, arbitrary definitions of weight regain are currently found in the literature [10]. These definitions include, but are not limited to: “any weight regain,” the percentage of total weight lost at nadir, the percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL), the percentage of weight change from nadir, or a minimum increase in kilograms [3, 5, 8, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Only two studies have compared measures of weight regain, by applying a number of different definitions of weight regain to the same post-bariatric cohort [8, 10]. Both studies found that the definition of weight regain drastically changed the reported outcomes. The first study applied six different definitions of weight regain to a small cohort (n = 55) of patients 5 years after SG. This led to weight regain rates ranging from 9 to 91% [10]. The second study applied five continuous and eight dichotomous measures to a large cohort of 1406 RYGB patients from the LABS-2 study, who were followed up until 5 years after surgery. Weight regain rates according to the eight dichotomous measures ranged from 44 to 87%, depending on the definition applied [8]. In this study, weight regain measures were also related to other clinical outcomes, such as diabetes.

Thus, studies on the definition of weight regain are still inconclusive. In addition, weight regain rates have not been explored in a European sample, nor in a sample including patients who have either undergone RYGB or SG. Further exploration of the associations of different definitions of weight regain with clinical outcomes is needed to develop a clinically relevant definition [10, 22]. Such a definition will help identify patients who experience weight regain and make it possible to investigate mechanisms causing long-term weight regain, thereby ultimately enhancing long-term treatment outcome.

To examine these issues more thoroughly, this study aims to replicate previous findings regarding weight regain prevalence 5 years after primary SG or RYGB, by applying six different definitions of weight regain, as applied in an earlier study, in a large cohort of bariatric patients [10]. Moreover, the clinical relevance of these definitions was determined by investigating which patient characteristics, such as demographic information, baseline BMI, and surgical procedure, were related to definitions of weight regain and by investigating the relationship between definitions of weight regain and HRQoL and comorbidity resolution at 5-year follow-up. We hypothesized that (1) the definition largely determines long-term weight regain prevalence; (2) the characteristics of patients who regain weight differ across definitions of weight regain; and (3) associations between weight regain and HRQoL and comorbidity resolution will vary by definition used.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Procedure

Patients were selected from the database of the Dutch Obesity Clinic (Nederlandse Obesitas Kliniek: NOK). Consisting of 8 care centers, the NOK is the largest, outpatient clinic group in the Netherlands that provides specialized multidisciplinary care for approximately one third of patients who undergo bariatric surgery. At the NOK, all patients are screened according to IFSO criteria [23]. In addition to bariatric surgery, patients follow an identical multidisciplinary treatment program involving a dietician, psychologist, physical therapist, and medical doctor, aiming to assist them in adopting and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. The treatment program consists of six group visits over 6 weeks prior to surgery to prepare patients for surgery and a comprehensive lifestyle change program for 12 months after surgery. Patients are followed up on a yearly basis, up to 5 years after surgery, after which patients are referred to their general practitioner for follow-up.

Patient Selection

All patients who underwent primary bariatric surgery between 2010 and 2013 were selected from the prospective database (n = 2490). Data was collected in two ways. First, 5-year outcome measures were derived from this database if patients had attended their 5-year follow-up appointment (n = 714). Second, to minimize loss to follow-up and selection bias, patients who had been lost to follow-up and underwent primary bariatric surgery 5 years prior to this study were invited to complete an online survey via email (n = 536). After giving their informed consent, patients filled in an online questionnaire which collected additional 5-year follow-up data. A total of 154 questionnaires were completed and found suitable for analysis. This led to a total of 868 out of 2490 patients being included in this study, with a loss to follow-up rate of 65%. Figure 1 shows the patient selection and recruitment process.

Patient recruitment and the questionnaires used were approved by the medical ethical committee of the VU medical center. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Measures

Demographic Information and Baseline Patient Characteristics

For all patients, baseline weight, height, demographics, surgical procedure, preoperative comorbidity, and HRQoL data were acquired from the database of the NOK. The demographics included age and gender.

Postoperative Weight

Postoperative weight was measured at follow-up appointments up to 5 years after surgery (12, 15, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months). Additional variables, including lowest postoperative weight (i.e., nadir), percent total weight loss (%TWL), and percent excess weight loss (%EWL), were calculated following standardized outcome reporting guidelines [24].

HRQoL Outcome Measures

HRQoL was assessed with the Dutch version of the RAND-36, which is a generic HRQoL questionnaire that consists of 36 questions divided into 9 scales: emotional role functioning, social functioning, vitality, physical functioning, mental health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, health change, and physical role functioning. Two subtotal scores can also be calculated: the physical health summary (PHS) and mental health summary (MHS). The RAND-36 has been validated for patients with extreme obesity [25, 26].

Comorbidity Measures

The presence of the following comorbidities was assessed at preoperative screening by a medical doctor: type 2 diabetes (DM2), dyslipidemia, hypertension, arthroses and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). At five-year follow-up, the status of these comorbidities was determined using the ASMBS guideline [24] (Brethauer). Since HbA1c and cholesterol measures were not available, this was based on patient-reported medication use and blood pressure at follow-up. The comorbidities were categorized as follows: complete remission, improved, unchanged, deteriorated, or de novo. Comorbidities categorized as “de novo” and “deteriorated” were so rare that these groups were too small for analysis. Therefore, comorbidity outcomes were grouped into present (improved, unchanged, deteriorated) or absent (in remission, never present) for our analysis.

Online Questionnaire

Patient data on weight, HRQoL, and comorbidity status at 5 years after surgery were gathered with the online questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of the Dutch version of the RAND-36. In addition, patients were asked to report their current weight, nadir weight, and status of comorbidities.

Definitions of Weight Regain

Nadir weight was determined based on all of the postoperative weight measures available. Weight regain at 5-year follow-up was calculated using five definitions of weight regain mentioned by Lauti et al. as being reported in the literature, as well as by Nedelcu et al. as collected in a social media poll among International Bariatric Club (IBC) surgeons [10, 22]. The current study added a sixth definition of 15% total weight regain from nadir, in accordance with recommendations to use %TWL when reporting weight loss. A 15% regain of total body weight from nadir has been repeatedly used after RYGB [4, 13, 18]. In total, the following six definitions were applied: (1) an increase > 10 kg from nadir, (2) an increase > 25%EWL from nadir, (3) an increase in BMI of 5 kg/m2 from nadir, (4) weight regain to a BMI > 35 kg/m2 after successful weight loss, (5) any weight regain, and (6) an increase > 15% of total body weight from nadir. The definitions and calculations can be found in Table 1.

Statistical Analyses

For all analyses, IBM SPSS statistical software version 24 was used. Independent t tests and chi-square calculations were performed exploring differences between patients who were selected from the database and patients who completed the online survey. Differences in weight regain rates 5 years after surgery and across the six definitions were explored using descriptive statistics. Multiple binomial logistic regression was used to explore the associations between demographics (i.e., age, gender, and preoperative BMI) or type of surgery (SG vs RYGB) and weight regain according to the different definitions 5 years after surgery, and to explore the associations between weight regain and the presence of comorbidities 5 years after surgery. Linear regression was used to explore the relationship between weight regain according to the different definitions and RAND-36 scores 5 years after surgery, adjusted for age, gender, preoperative BMI, surgical procedure, and RAND-36 scores at 2 years after surgery. Assumptions regarding regression were tested and met. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

A total of 868 patients were included in this study, of which 5-year follow-up data was available for 714 patients and 154 patients filled in an online questionnaire. Patients who completed the questionnaire were younger (44.1 ± 11.1 vs 46.6 ± 10.4, p = 0.011) and more likely to be female (89% vs 77%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia at baseline was lower in patients who filled in the online questionnaire. Regarding HRQoL, patients who filled in the online questionnaire had lower scores on the physical health scale of the RAND-36 at 5-year follow-up and higher scores on the mental health scale. Weight data did not differ between groups (see Table 2).

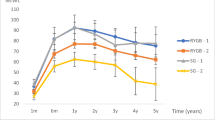

Weight Regain Rates and Associations with Patient Characteristics

At 5-year follow-up, mean %TWL was 25.8% and average weight gain from nadir was 10%. The majority of patients experienced some weight regain at 5-year follow-up: 87% of patients regained weight according to the “any weight regain” definition. In the remaining definitions, percentages of patients classified as experiencing weight regain ranged from 16 to 37% (see Table 3). Percentage TWL is presented in Fig. 2 for all patients and for every weight regain group separately.

After adjustment for all factors, age, preoperative BMI, and surgical procedure were associated with a number of definitions (see Table 4). Higher age was associated with a lower likelihood of experiencing weight regain in three definitions. Higher preoperative BMI was associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing weight regain in three definitions (definitions I, III, and IV) and a lesser likelihood of experiencing weight regain in one definition (definition II). Surgical procedure was significantly related to weight regain in only one definition: patients who underwent SG were more likely to experience weight regain when the > 25%EWL definition was applied than patients who underwent RYGB.

Weight Regain and HRQoL

Weight regain was negatively associated with the PHS of the RAND-36. This association was statistically significant in half of the definitions (see Table 5). No significant relationship between definitions of weight regain and the MHS of the RAND-36 was found.

Weight Regain and Comorbidity Status

Only two associations between the weight regain definition and the presence of comorbidities at 5-year follow-up were statistically significant. Patients who met the criteria of an increase of > 10 kg from nadir or weight regain to a BMI > 35 kg/m2 after successful weight loss were more likely to be diagnosed with OSA at 5-year follow-up (see Table 6).

Discussion

Exploring the long-term prevalence of weight regain in a large sample of Dutch patients who had undergone RYGB or SG, the present study found that the prevalence differs greatly depending on which of six different definitions is used, with weight regain rates ranging from 16 to 87%. In addition, the factors related to weight regain differed for each of these definitions. A higher preoperative BMI and a younger age at the time of bariatric surgery were related to a greater likelihood of experiencing weight regain in three definitions. SG surgery was related to a greater likelihood of experiencing weight regain in one of the six definitions. Three definitions of weight regain were related to deterioration in HRQoL according to the PHS of the RAND-36. Associations with the presence of comorbidities at 5-year follow-up were weak.

As expected, the definition of weight regain greatly influenced weight regain prevalence. Interestingly, the prevalence (16–87%) was considerably lower than in previous studies. The study by Lauti et al. found a prevalence ranging from 40 to 91% according to the same definitions as the present study [10]. The study by King et al. included 1286 of 1406 patients in the weight regain sample, meaning 91% of patients had regained weight. Of this 91%, 44–62% experienced significant weight regain according to the definitions that were also used in the present study [8]. In the present study, percentages were considerably lower, at 21–37%. This might be partly explained by the lower preoperative BMI in the present sample compared to the sample of Lauti et al., as higher preoperative BMI is associated with a greater likelihood of weight regain. However, in the study by King et al., preoperative BMI was comparable to the present study [8, 10].

Another explanation might be that the treatment program of the NOK is different to the “general” bariatric surgery center. In line with recommendations, patients at the NOK follow an intensive multidisciplinary treatment program before and after surgery focusing on changing dietary and physical activity behavior [23, 27, 28]. Research has shown that long-term multidisciplinary support is important for maintaining positive changes after bariatric surgery and may play a role in preventing weight regain [29, 30]. Another study showed similar weight loss trajectories to the present study [7]. Unfortunately, it is difficult to compare this study to others because of the different definitions used, as well as different, or variable, follow-up periods [4, 5]. This emphasizes the need for consensus and standardized outcome reporting of weight regain.

The results confirm that some weight regain occurs in the vast majority of patients who undergo bariatric surgery, with 87% of the total population experiencing “any weight regain,” which is in agreement with several other studies [6,7,8, 12, 31]. These results suggest that some regain is normal, rather than clinically significant.

Preoperative BMI was positively related to weight regain when definitions were based on changes in BMI, %EWL, and kilograms. Recent studies have also shown that weight loss measures based on %EWL or BMI are influenced by preoperative BMI, and this study confirms that these measures are less suitable for comparing patients [32,33,34,35].

Interestingly, age was inversely related to weight regain, which has been described previously [13]. One possible explanation is that younger patients represent a high-risk group, in which problems related to weight gain are more severe. Future research into weight regain risk at a younger age and targeting regain with additional interventions is needed.

Since HRQoL is considered to be one of the key outcomes of bariatric surgery, clinically significant weight regain should be associated with deterioration of HRQoL [36]. Three definitions of weight regain (regain > 10 kg, regain 5 BMI, and regain EWL 25) were related to the physical health component of the RAND-36, measuring HRQoL. Several studies have shown that HRQoL improves after bariatric surgery and that this improvement is related to the amount of weight lost [3, 37,38,39]. They also show stronger associations with the physical health component than the mental health component [38, 40]. Contrary to expectations, the negative association of weight regain with HRQoL was not significant in the > 15%TWR definition. This may be due to the fact that the RAND-36 is a generic HRQoL questionnaire, which might not be sufficiently sensitive to capture changes in HRQoL as a result of bariatric surgery [41]. Therefore, the percentage of 15% might be too small to be clinically significant.

The other key outcomes related to weight regain data were comorbidities at 5-year follow-up. These associations were weak for all definitions of weight regain. Only weight regain > 10 kg and weight regain to a BMI > 35 were significantly related to one comorbidity—that of OSA. These results suggest that none of the six definitions is suitable to predict key clinical outcomes with respect to comorbidities.

In one of the previous studies, a continuous measure that was quantified as a percentage of maximum weight lost performed best on association with clinical outcomes [8]. This is in line with the fact that measures based on kilograms, BMI, or %EWL are not suitable to compare patients with different BMI [32, 34]. A measure reflecting a percentage of total weight loss or regain would, therefore, be more suitable, especially since percentage of total weight loss is now the measurement of choice when reporting weight loss after bariatric surgery [24].

One can argue whether there is a need for a definition of significant weight regain if there is a solid definition of surgical success. Van de Laar et al., for example, suggested that a definition of weight regain would be unnecessary if a cutoff curve for weight loss success was used [34]. Weight regain from that perspective is only relevant if it exceeds the point where surgery is no longer considered a success. However, not differentiating between insufficient weight loss and weight regain ignores the possibly different mechanisms causing weight regain or weight loss failure. Patients experiencing weight regain may benefit from different interventions than patients who experience insufficient weight loss.

All current definitions of weight regain and successful weight loss only use a measure of body weight to define success, ignoring health status and patient experience of weight loss failure or relapse [4, 5, 8]. Ideally, other key outcomes after bariatric surgery, such as improvement or remission of comorbidities and improvement of HRQoL, should also be included when defining whether weight regain is significant [42]. Developing such a clinically relevant definition that takes all important dimensions into account is challenging and, therefore, it should not only involve scientific and clinical experts but also patients, with the aim of reaching worldwide consensus.

The most significant limitation of this study is that the loss to follow-up percentage at 5 years after surgery was 70%. With the inclusion of patients who filled in an online questionnaire, this was still 65%. This is a known problem in most studies of bariatric surgery, with mean compliance at long-term follow-up low [43]. As a result, this study relied, in part, on self-report measures for patients who were recruited to complete an online questionnaire. Differences between patients included in the NOK database and the patients who completed the online questionnaire were small. The status of comorbidities was determined by a medical doctor based on patient-reported medication use and blood pressure. Because HBA1c and cholesterol measures were not available, smaller differences in the status of a comorbidity may have been overlooked. As a result, associations between weight regain and comorbidities may have been more difficult to establish. Another limitation is that the proportion of patients who underwent SG was relatively small. Despite the loss to follow-up, this study still involved a large sample. It is the first study to apply different weight regain definitions to such a large sample of patients who have undergone RYGB or SG and thus provides comprehensive insight into the prevalence of weight regain and its associations with clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

The lack of consensus regarding definitions of weight regain results in great variation in measures of prevalence (16–87%). If weight regain itself was considered as one distinct dimension of surgery success, the percentage of weight change from nadir would be the most suitable measure to compare patients and results. However, treatment value should not only be measured by a percentage of weight change. Some weight regain definitions were associated with deterioration in physical HRQoL, while associations between definitions of weight regain and the presence of comorbidities 5 years after surgery were weak. These results indicate that most of the dichotomous definitions of weight regain that are currently used are of little clinical significance. Hence, identifying one single categorical definition of weight regain, which reflects important clinical outcomes, is difficult. Therefore, additional research into the clinical significance of weight regain is needed to inform the development of a standardized definition of weight regain that considers all the important dimensions of surgery success: weight, HRQoL, and comorbidity remission.

References

Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The BMJ. 2013;347:f5934.

Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219–34.

Karlsson J, Taft C, Rydén A, et al. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study [Original Article]. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1248.

Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X, et al. Weight recidivism post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1922–33.

Lauti M, Kularatna M, Hill AG, et al. Weight regain following sleeve gastrectomy—a systematic review [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2016 June 01;26(6):1326–34.

Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143–55.

Lent MR, Hu Y, Benotti PN, et al. Demographic, clinical, and behavioral determinants of 7-year weight change trajectories in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 2018/07/30/.

King WC, Hinerman AS, Belle SH, et al. Comparison of the performance of common measures of weight regain after bariatric surgery for association with clinical outcomes. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1560–9.

Neto RML, Herbella FAM, Tauil RM, et al. Comorbidities remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity is sustained in a long-term follow-up and correlates with weight regain [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2012;22(10):1580–5.

Lauti M, Lemanu D, Zeng ISL, et al. Definition determines weight regain outcomes after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1123–9.

Freire RH, Borges MC, Alvarez-Leite JI, et al. Food quality, physical activity, and nutritional follow-up as determinant of weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Nutrition. 2012;28(1):53–8.

Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery (labs) study. JAMA Surgery. 2017;

Shantavasinkul PC, Omotosho P, Corsino L, et al. Predictors of weight regain in patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(9):1640–5.

Bradley LE, Forman EM, Kerrigan SG, et al. A pilot study of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight regain after bariatric surgery [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2016;26(10):2433–41.

Bradley LE, Forman EM, Kerrigan SG, et al. Project HELP: a remotely delivered behavioral intervention for weight regain after bariatric surgery [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):586–98.

Amundsen T, Strømmen M, Martins C. Suboptimal weight loss and weight regain after gastric bypass surgery—postoperative status of energy intake, eating behavior, physical activity, and psychometrics [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2017;27(5):1316–23.

Cooper TC, Simmons EB, Webb K, et al. Trends in weight regain following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) bariatric surgery [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1474–81.

Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, et al. Behavioral predictors of weight regain after bariatric surgery [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2010;20(3):349–56.

Yanos BR, Saules KK, Schuh LM, et al. Predictors of lowest weight and long-term weight regain among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1364–70.

da Silva FBL, Gomes DL, de Carvalho KMB. Poor diet quality and postoperative time are independent risk factors for weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Nutrition. 2016;32(11):1250–3.

Himes SM, Grothe KB, Clark MM, et al. Stop regain: a pilot psychological intervention for bariatric patients experiencing weight regain [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):922–7.

Nedelcu M, Khwaja HA, Rogula TG. Weight regain after bariatric surgery—how should it be defined? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):1129–30.

Fried M, Yumuk V, Oppert JM, et al. Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2014;24(1):42–55.

Brethauer SA, Kim J, el Chaar M, et al. Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(3):489–506.

VanderZee KI, Sanderman R, Heyink JW, et al. Psychometric qualities of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0: a multidimensional measure of general health status. Int J Behav Med. 1996;3(2):104–22.

Al Amer R, Al Khalifa K, Alajlan SA, et al. Analyzing the psychometric properties of the Short Form-36 Quality of Life Questionnaire in patients with obesity [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2018;28(8):2521–7.

Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery(). Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2013;21(0 1):S1-27.

Tettero OM, Aronson T, Wolf RJ, et al. Increase in physical activity after bariatric surgery demonstrates improvement in weight loss and cardiorespiratory fitness [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2018 August;13

Coulman KD, MacKichan F, Blazeby JM, et al. Patient experiences of outcomes of bariatric surgery: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(5):547–59.

Gould JC, Beverstein G, Reinhardt S, et al. Impact of routine and long-term follow-up on weight loss after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3(6):627–30.

Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, et al. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2008;18(6):648–51.

Corcelles R, Boules M, Froylich D, et al. Total weight loss as the outcome measure of choice after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2016;26(8):1794–8.

Karmali S, Birch DW, Sharma AM. Is it time to abandon excess weight loss in reporting surgical weight loss? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(4):503–6.

van de Laar AW, van Rijswijk AS, Kakar H, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of 50% excess weight loss (50%EWL) and twelve other bariatric criteria for weight loss success [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2018;27

van de Laar A, de Caluwé L, Dillemans B. Relative outcome measures for bariatric surgery. Evidence against excess weight loss and excess body mass index loss from a series of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2011;21(6):763–7.

Coulman KD, Hopkins J, Brookes ST, et al. A core outcome set for the benefits and adverse events of bariatric and metabolic surgery: the BARIACT Project. PLoS Med. 2016;13(11):e1002187–7.

Monpellier VM, Antoniou EE, Aarts EO, et al. Improvement of health-related quality of life after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass related to weight loss. Obes Surg. 2017;27(5):1168–73.

Sarwer DB, Steffen KJ. Quality of life, body image and sexual functioning in bariatric surgery patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):504–8.

Lindekilde N, Gladstone BP, Lübeck M, et al. The impact of bariatric surgery on quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(8):639–51.

Kolotkin RL, Kim J, Davidson LE, et al. 12-year trajectory of health-related quality of life in gastric bypass patients versus comparison groups. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(9):1359–65.

Müller A, Crosby RD, Selle J, et al. Development and evaluation of the Quality of Life for Obesity Surgery (QOLOS) Questionnaire [journal article]. Obes Surg. 2018;28(2):451–63.

Coulman KD, Howes N, Hopkins J, et al. A comparison of health professionals’ and patients’ views of the importance of outcomes of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg, 26. 2016;(11):2738–46.

Puzziferri N, Roshek TB, Mayo HG, et al. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312(9):934–42.

Acknowledgments

The contribution of MvS is supported by the Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Veni from NWO-MaGW (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research—Division for the Social Sciences, project number 451-16-018). Editorial support was provided by Nicholas Paquette, PhD (Medtronic).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards for studies involving human participants.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

V. Voorwinde and V.M. Monpellier are employed by the Dutch Obesity Clinic. I.M.C. Janssen is the medical director of the Dutch Obesity Clinic. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Voorwinde, V., Steenhuis, I.H.M., Janssen, I.M.C. et al. Definitions of Long-Term Weight Regain and Their Associations with Clinical Outcomes. OBES SURG 30, 527–536 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04210-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04210-x