Abstract

Contemporary sustainability issues require the integration of diverse knowledge to study and address them holistically. How interdisciplinary knowledge integration arises in teamwork is, however, poorly understood. For instance, studies often focus on either individual or team processes, rather than studying their interplay and thereby contributing to understanding knowledge integration in an integral manner. Therefore, in this study we aimed to understand how knowledge integration processes are shaped by interactions in interdisciplinary teamwork. We present insights from an ethnographic case study of interdisciplinary teamwork among eight master’s students. In this student team, we observed two dynamics that impeded knowledge integration: (1) conformative dynamic manifested as avoiding and ignoring differences, and (2) performative dynamic as avoiding and ignoring not-knowing. Based on earlier work, we expected that contributing one’s own and engaging with each other’s knowledge would ensure knowledge integration. However, the dynamics exposed that it did not only depend on whether knowledge was contributed and engaged with, but also which knowledge was exchanged and manipulated in the teamwork. We coin the concept ‘relative expertise’, which emphasizes that interdisciplinary teamwork requires that collaborators act simultaneously as expert—in relation to their own contributory expertise—and non-expert—in relation to others’ contributory expertise. The dynamics hampered acting as a relative expert, and we saw that this was shaped by an interplay of students’ individual epistemic competencies, shared assumptions about teamwork, and social context. The insights may help recognize dynamics and underlying factors that impair knowledge integration, and thereby inform targeted interventions to facilitate knowledge integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Contemporary sustainability issues—such as climate change, resource scarcity, pollution, ever-growing healthcare demands, and global inequalities—are complex problems that transcend boundaries of academic disciplines (McArthur and Sachs 2009; Jerneck et al. 2011; Holm et al. 2013; IPCC 2022). As such, scientific research aiming to understand and address these issues requires interdisciplinary approaches (Rylance 2015). Through those approaches, knowledge and insights from different fields can be brought together to gain a more comprehensive understanding of complex sustainability issues and address them more holistically than what is possible when approaching them from a single disciplinary perspective (Boix Mansilla 2005; Clark et al. 2016). This goal, however, requires that experts from different fields collaborate (Fiore 2008; Ryser et al. 2009) and they integrate their knowledge (Klein 2017). Interdisciplinary knowledge integration goes beyond the accumulation and mechanistic pooling of knowledge from different fields. Rather, it requires relating elements often previously unrelated to create new meanings and actions (Klein 2017; Pohl et al. 2021).

Diversity of perspectives that collaborators from different disciplinary backgrounds bring, then, is essential to interdisciplinary collaboration (Vilsmaier and Lang 2015). This diversity provides opportunities to gain a more comprehensive and layered understanding of sustainability concerns (Dahlin et al. 2005; Crowley and O’Rourke 2020). However, diversity is also at the root of challenges of interdisciplinary collaboration, including misunderstandings and misaligned goals (Cronin and Weingart 2007). Disciplines differ in language, practices, methods, and theories that cause challenges in collaboration (Morse et al. 2007; Regeer and Bunders 2009). Different disciplines are also founded on different values systems and assumptions about knowledge and research as the practice of generating knowledge and attendant or epistemic cultures (Grin and Van De Graaf 1996; Knorr-Cetina 1999; Eigenbrode et al. 2007). Interdisciplinary collaboration requires dealing with these differences to exchange knowledge and to make sense together of the topic under study (Kjellberg et al. 2018). This expectation does not mean interdisciplinary collaboration is aimed explicitly at reaching consensus (Boix Mansilla 2017; O’Rourke 2017; Pohl et al. 2021). Rather, teamwork should use difference as a resource to enrich understanding of a topic without smoothing over disciplinary differences (Souto 2015; Vilsmaier and Lang 2015).

Engaging in interdisciplinary collaboration and integration is also highly demanding of teams as well as individuals, requiring competencies in knowledge integration that are both individual- and team-based (Parker 2010; Misra et al. 2015; Lotrecchiano et al. 2020; Bammer et al. 2020; Pennington et al. 2021; Horn et al. 2022). Insufficient mastery of these competencies has proven to cause conflict among collaborators (Strober 2006) and results in superficial interdisciplinary work (Boix Mansilla 2005). Besides competencies of individual collaborators, interdisciplinary knowledge integration has also been shown to rely on team dynamics (Salazar et al. 2012; Boix Mansilla et al. 2016). Among other traits, psychological safety and trust, power, motivation, team diversity, and disciplinary compatibility shape interdisciplinary teamwork (Salazar et al. 2012; Lotrecchiano et al. 2016; Boix Mansilla et al. 2016; O’Rourke et al. 2019). As a result, both low competence levels and unfavorable team dynamics can impair interdisciplinary collaboration and integration (Salazar et al. 2012; Freeth and Caniglia 2020). Studies of teamwork affirmed it is essential to take an integrative approach that considers both individual and social systemic levels, because they are concurrent and interdependent for understanding team functioning and learning (Volet et al. 2009; Decuyper et al. 2010).

Although a wealth of literature exists about competencies and teamwork for interdisciplinarity, individual and team level processes are often studied in relative isolation, whereas they are known to interact and jointly shape knowledge integration in teams (DeCuyper et al. 2010). The literature provides definitions of knowledge integration (e.g. Pohl et al. 2021), and/or descriptions of factors that affect the development of integrated insights (e.g. Salazar et al. 2012; Boix Mansilla et al. 2016; Pennington et al. 2021), but they report that a need remains to better understand the underlying mechanisms—how these diverse factors affect knowledge integration (Pohl et al. 2021). As knowledge integration is considered key to interdisciplinary work, the lack of knowledge about how it comes about, and—related to that—how it can be facilitated, hamper interdisciplinary practice. This knowledge gap, therefore, hampers design and implementation of educational interventions as well as project management for sustainability research, because understanding of mechanisms that could inform targeted intervention is lacking.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to understand how interactions in interdisciplinary teamwork shape team knowledge integration processes. In order to do so, we present insights from a case study of interdisciplinary teamwork among eight master’s students. We describe how our student team behaved and which factors affected their knowledge integration process. Our findings exposed two behavioural dynamics that impaired their knowledge integration. These observations triggered us to develop a conceptualization of the need to act as a ‘relative expert’ in interdisciplinary teamwork, taking on the role of expert in relation to one’s own expertise and of non-expert in relation to others’ expertise. Moreover, we demonstrate the difficulty of this behaviour and distill personal and team level factors that play a role in those dynamics.

Methods

To gain insight into how individual competencies and team level processes jointly shape team knowledge integration processes, we took an ethnographic approach (Bath 2009). Through this approach, we intensively and closely observed, guided, and studied the functioning of one student team engaging in interdisciplinary teamwork on a complex sustainability issue in the context of a master’s level course over a period of 5 months.

Setting

The data collection for this study took place in the context of the 2021 offering of the course Interdisciplinary Community Service Learning 2 (iCSL2): Addressing Challenges through Transdisciplinary ResearchFootnote 1 (described in more detail in Tijsma et al. 2023). In this course, master’s students from different departments and faculties across VU Amsterdam collaborate in teams. As part of course requirements, they worked on the broad sustainability topic of a Circular Economy. Each student conducted research in the context of his or her master’s program, meeting its requirements and under supervision of an expert from their own department while viewing the topic through the lens of their own fields (theories, methods, approaches, etc.). They voluntarily took the iCSL2 course on top of, and in parallel to, their individual research projects as an extracurricular elective course. In the course they were tasked with integrating insights from their individual projects into a single report. The course ran for 5 months (February–June), and centered around weekly team meetings with the explicit aim of supporting them in the process of integrating knowledge from their individual projects. These meetings were guided by the second author, assisted by the first author. All team meetings (n = 21) in the 2021 offering took place online via Zoom, due to restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, and—depending on content, team needs, and project stage—were between 1 and 2 h in length.

Participants and data collection

In keeping with ethnographic methodology, data collection involved a combination of observations, qualitative interviews, and analysis of written reflection reports. Over the entire course, we conducted observations of the work and interactions of one student team. It consisted of eight students, seven in master’s and one in a PhD program. They were enrolled in the following programs: Business Administration: Strategy and Organization; Digital Business Innovation; Environment and Resource Management; Food Innovation and Healthy Food Design; Management, Policy Analysis, and Entrepreneurship in the Health and Life Sciences; Science and Technology Policy (PhD); and Work and Organizational Psychology (n = 2). Moreover, their master’s programs did not necessarily correspond to monodisciplinary backgrounds. They exhibit varying breadth with different degrees of specialization. Students also combined different bachelor’s and master’s programs, and some were completing multiple degrees in different fields. Thus, the students held diverse academic identities with varying breadth and depth in one or multiple disciplines. Consequently, students also represented a wide range of experience with interdisciplinary work. Besides disciplinary diversity they were also diverse in cultural backgrounds, and the main language of the course—English—was a first tongue for only one student.

We recorded audio and video of all meetings via Zoom. During and immediately after the meetings, the first author took extensive notes in an observational journal. These notes were guided by a gradually developing understanding of the knowledge integration process that arose through continuous conversations and joint reflections between the first and second authors. Throughout the course (during weeks 1–9, 11, 15, 17, 19, and 21), the students completed individual written reflection exercises in English. Moreover, we conducted four semi-structured interviews with each student (during weeks 3, 7, 13 and 21). We followed an interview protocol that outlined objectives of an interview, and formulated questions based on the completed written reflection exercises. The interviews focused on students’ departure points in terms of expectations, backgrounds, and competencies (interview #1 in week 3), differences in disciplinary perspectives among team members (interview #2 in week 7), collaboration among students (interview #3 in week 13), and the entire collaboration process in terms of team dynamics as well as collaboration and integration towards joint end results (interview #4 in week 21). The first author conducted these interviews via Zoom and they lasted for approximately 1 h each. If the first language of the student was Dutch (4/8), we conducted the interviews in Dutch, otherwise in English. We transcribed the interviews verbatim.

Data analysis

Interpretation of data began with writing of reflective observational journals and ongoing conversations among the authors. In the analysis, we built onto our earlier work, in which we characterized four types of student behavior in interdisciplinary teamwork—naive, assertive, accommodating, and integrative—and two sets of epistemic competencies for interdisciplinary teamwork—epistemic steadiness and epistemic adaptability (Horn et al. 2022). We applied this conceptualization as an analytical framework to distinguish behaviours and competencies in relation to knowledge integration in the teamwork.

Based on our earlier work (Horn et al. 2022) we expected the students to achieve knowledge integration when we stimulated them to contribute their knowledge and to engage with knowledge contributions of others. However, already in an early stage of our fieldwork, we noticed that the contribution of and engagement with knowledge did not guarantee the building of shared understanding in the team. Through the ongoing process of taking, analyzing and discussing fieldnotes, two behavioural dynamics emerged through an inductive, iterative analysis process in which we identified lower level codes for behaviours that we observed and which we present underlined in the Findings section (e.g. ‘not bring alternative explanations’ and ‘simplify contributions’). We clustered these into two higher level themes, the two behavioural dynamics: (1) conformative and (2) performative team dynamics.

The surprising observation that contributing and engaging with each other’s knowledge did not suffice for knowledge integration processes served as the starting point for our subsequent abductive reasoning (Kovács and Spens 2005; Le Gall and Langley 2015). This observation challenged our original assumption and sparked two refined research questions in us: (1) how do the dynamics that we observed shape knowledge integration processes? And; (2) what personal and team level factors shape those team dynamics and thereby challenge knowledge integration? To answer the first question, we turned to literature, based on which we propose the conceptualization of acting as a ‘relative expert’, which we further explain in the Findings section. Subsequently, we applied this concept to our data in understanding the behavioural dynamics. To answer the second question we conducted a parallel inductive–deductive analysis of the data, in which we identified behaviours and competencies based on our earlier work (Horn et al. 2022) and inductively identified other factors and the interactions between factors (e.g. ‘familiarity’, ‘online setting’).

Research ethics

All students who participated in the study provided written informed consent about use of their data for scientific research and the possibility of discontinuing their participation in the study at any time, without consequences for participation in the course or relationship with the teaching staff. All of the students who participated in the course opted to continue and to participate in this study. The findings are reported anonymously, by referring to all students in female form and avoiding and removing any identifiable information such as study backgrounds and details about their individual projects. The ethical committee of VU Amsterdam also gave ethical approval for the research project in the context of which findings in this publication are represented.

Findings

Two team dynamics: conformative and performative

While supervising our team, two dynamics in their interactions stood out to us. Already during the observations, these patterns of team dynamics started to emerge, and our understanding and definition of these dynamics gradually developed over the process of data collection and analysis to arrive at the final understanding we present here. Through this process we arrived at the terms ‘conformative’ and ‘performative’ dynamics that we coin in this article. In this subsection, we describe how these dynamics manifested as team level interactions.

Conformative dynamic

The conformative dynamic was a tendency among students to agree with each other’s ideas and contributions. Hence, they steered away from differences of opinion and disagreements. The conformative dynamic was particularly salient in decision-making processes. For instance, in the process of framing their joint research by defining research questions or key concepts, they often quickly settled for a decision through implicit agreement with the first suggestion that came up, rather than critically examining different alternative understandings and views. To illustrate this, the following quote provides an example of this recurring pattern. This example is about how the team defined the key concept of circular economy for their project:

“I suggested this conceptualization of the circular economy based on 3 Rs. [Reduce, Reuse, Recycle] [...] I was surprised that no other definitions were suggested, because I think there are like 40 different Rs to make sense of circular economy. That decision was really made because I made that suggestion and it was just accepted by the others. [...] Now I don’t know whether it was accepted because it is a definition that everyone agrees with or whether they just thought: sure, that’s fine.” - S6 interview 3.

In this example, S6 suggested a definition of circular economy for the framing of their joint project, and this definition was directly and partly implicitly accepted and not complemented by alternative definitions that the team discussed and compared, nor questioned by the other team members. They thus conformed to contributions by others, rather than diverging and diversifying.

Performative dynamic

The performative dynamic was a tendency of the students to pursue a linear process characterized by certainty, without reconsidering statements or decisions. Hence, they steered away from uncertainty, ambiguity, and not-knowing. This dynamic was in particular prevalent in the way the students dealt with (critical) questions and feedback, either from each other or from the teachers. We observed a reluctance to revisit, revise, challenge, and question decisions or statements that they had made. This was, for instance, reflected in discomfort and frustration the students expressed experiencing about the iterative and unclear nature of the collaboration process. They expressed that having to revise their questions and concepts repeatedly caused their motivation to drop, and that they did not feel like they made any progress until they started writing their report and thus started to put actual words on paper. S2 put it as follows:

“We had our main question, however after the presentation we changed the question again to make it a bit more specific. I feel like every time we make a little progress but maybe not as much.”—S2 reflection week 7

This quote illustrates a behaviour we observed repeatedly in the team. Receiving feedback and revisiting the questions thus to her seemed akin to taking a step back, undoing rather than making progress. This demonstrates what we call the performative dynamic, a strive for progress as defined by outcome, performance, and increased certainty and clarity.

Team dynamics and knowledge integration

The dynamics described in the previous subsections seemed to be disruptive to knowledge integration processes in the team. Both the conformative dynamic and the performative dynamics caused the conversations to quickly converge and prevented the diversification and exploration of the knowledge represented in the conversation and thereby prevented the use of the knowledge represented in the knowledge bases of the students. These observations confirm and expand on our previous work (Horn et al. 2022). It confirms the earlier finding that the absence of contributing and engaging with knowledge impairs knowledge integration, as we observed instances in which the dynamics manifested as an absence of contributing and engaging with knowledge. On top of that, we also observed cases in which the students did contribute and engage with knowledge, but in which knowledge integration processes were still impaired. This observation led us to ask the question whether the development of shared understanding does not only rely on the basis that knowledge is contributed and engaged with, but also which knowledge is contributed and engaged with, which we address in the upcoming subsections. This is thus an expansion of our earlier work (Horn et al. 2022), adding the additional focus on which knowledge is contributed and engaged with to the framework we developed in the past.

Knowledge and expertise in interdisciplinary teamwork

Interactional expertise as locus of interdisciplinary teamwork

To understand the significance of which knowledge collaborators exchange in interdisciplinary teamwork, we turned to the ‘periodic table of expertises’ as put forward by Collins and Evans (2007). Based on their observations on how sociologists of science engaged with the scientific communities they studied, they distinguished between two forms of specialist knowledge: interactional and contributory expertise (Collins and Evans 2007). The members of the scientific communities under study, on one hand, held contributory expertise; the advanced understanding of key theories and methodologies in their field, to the extent of being able to use and apply them to develop new knowledge within their domain of expertise, but also explain them to others and train others in them. The sociologists of science, on the other hand, developed interactional expertise; understanding of the field they study that allowed them to understand and engage in conversation with experts from the field, but did not allow them to train others in it or actively engage in the development of new knowledge within those fields. They acquired this expertise through the interaction with the experts, hence the term interactional expertise.

Collins and Evans (2007) themselves defined interactional expertise as the “medium of interchange in properly interdisciplinary, as opposed to multidisciplinary, research” (p.32) Stephens and Stephens (2021) further built upon this in making sense of teams engaging in interdisciplinary teamwork, as expert networks. Those networks consist of experts who hold contributory expertise in their own field and hold (and/or are in the process of developing) interactional expertise in the fields of their consortium members from other fields (Stephens and Stephens 2021). This means that collaborators hold the status of expert within their own disciplinary scope—that which they hold contributory expertise on—they bring their knowledge and abilities to the team and constantly judge what knowledge they should share with the team, and with how much technical detail (Stephens and Stephens 2021). Simultaneously, they develop interactional expertise in their collaborators’ fields, through demonstrating interest and curiosity, and the utilitarian requirements to understand each other’s work for the joint work to progress (Stephens and Stephens 2021). This demonstrates that in the context of interdisciplinary teamwork, the building of interactional expertise is considerably different from its development in the context in which the concepts originally emerged, when sociologists of science immersed themselves in scientific communities (Collin and Evans 2002). Rather than an interaction in which one party is the specialist that brings the contributory expertise and the other is relatively unknowledgeable and acquires interactional expertise, both parties need to take on both roles.

Acting as a relative expert to build shared understanding

So, bringing those insights together, we coin the concept of ‘relative expert’; collaborators in interdisciplinary teamwork need to combine two seemingly contradictory roles: of expert and of non-expert. In relation to their own contributory expertise, they take on a role of expert, explaining what they know to others while indicating their levels of certainty and indicating boundaries of their personal knowledge; thus acting epistemically stable (Horn et al. 2022). In relation to topics on which they do not hold contributory expertise, they take on the role of non-expert, indicate not-knowing, asking questions to others who do possess knowledge about it, and actively committing to understanding through follow-up questions and critical inquiry; thus acting epistemically adaptable (Horn et al. 2022).

Returning to the question which knowledge is to be exchanged in interdisciplinary teamwork, this thus stresses the importance of contributory expertise. To support the building of shared understanding, collaborators should focus their efforts in contribution knowledge on their own contributory expertise. In addition, in engaging with others’ knowledge, the focus should be on others’ contributory expertise. This should, however, be an interactive process in which collaborators depend on and respond to each other’s behaviours. After all, one can only engage with what others have shared and only when they share something can others engage with this. This thus asks for a dialogical interaction in which collaborators constantly switch between and dynamically navigate the roles of expert and non-expert and the corresponding behaviours.

Knowledge interactions in a student team

With the conceptualization of taking on the role of relative expert in mind, we returned to the interactions in the student team we followed and supervised and used the analytical lens of relative expertise and different expertises and knowledge types to make sense of the dynamics and their impact on the development of shared understanding among the students. In the following two sections we describe which knowledge students contributed and engaged with in the conformative and performative dynamics, respectively.

Conformative knowledge behaviours

As we discussed at the beginning of the Findings section, the conformative dynamic manifested as a tendency of the students to agree with each other’s ideas and contributions and to thereby steer clear of differences of opinion and disagreements. When looking at the conformative dynamic through the lens of relative expertise and Collins and Evans’ (2002) types of expertise, we saw that the students often either did not contribute any knowledge, or that they contributed knowledge that was already shared and/or (expected to be) uncontested; this nudged them towards bringing non-specialist rather than contributory knowledge, as everyday knowledge was more likely to be familiar and thus meet an appreciative response and little resistance. In terms of engaging with knowledge, we saw that it was either absent altogether, or the engagement was uncritical.

In the example that we gave when introducing the concept of conformative dynamics, the absence of contributing and engaging with knowledge was pronounced. We saw that the students did not bring alternative definitions—and thus did not bring their contributory expertise—and did not question the definition that was brought in—and thus did not engage with others’ contributory expertise.

We also observed instances at which students contributed knowledge but not their contributory knowledge. This could manifest as simplifying contributions, for instance by avoiding concepts and jargon. S8 wrote the following:

“For the presentations and discussions I did not have many questions, as most people tried to keep specific words out and explain it so everyone could understand what they wanted to do.”—S8 (week 4)

By not using jargon, students seemed to prevent lack of clarity and corresponding difficulties. However, at the same time, consequently they also removed some of the disciplinary specificity and depth of their contributions, and brought less contributory expertise to the joint effort. As S8 indicated, the simplified contributions by her teammates also reduced the questions it sparked in her and thus also prevented her from engaging with her teammate’s expertise.

When students were confronted with knowledge contributions different from their own, we saw they often neglected rather than critically engaged with those differences. They dealt with differences by accepting but not further exploring them. Rather than exploring the underlying causes of these differences, they took note of differences, but left them otherwise untouched. S7 wrote the following about differences and disagreements:

“There were no real disagreements. We talked about the things we did not understand about each other’s articles but generally seem to accept that others have a different way of saying what good scientific knowledge is and what important is for to judge a published article”—S8 reflection week 5

In this quote, S8 demonstrated she took note of differences in perspectives and epistemological views, and she was not only accepting but also trying to empathize with them. However, she did not stress the criticality of addressing differences when collaborating and did not consider them sources of information and as a starting point for exploring the topics. This means that they did not take the opportunity to engage with each other’s unique contributory knowledge bases, but instead limited themselves to the knowledge that was already shared.

Overall, we thus saw that the conformative dynamic was a manifestation of not (fully) acting as a relative expert by contributing their own and engaging with others’ contributory unique expertise. The conformative dynamic was characterized by non-expert behaviour, also in relation to one’s own expertise.

Performative knowledge behaviours

As we discussed earlier, the performative dynamic manifested as a tendency to pursue a linear, certain process by steering clear of uncertainty, ambiguity, and not-knowing. We saw that instead of bringing their own contributory expertise, the performative dynamic meant that students often brought non-specialist knowledge to the teamwork. In addition, instead of engaging with others’ contributory knowledge, they tended to engage with non-novel knowledge that they themselves already held and was thus not the unique contributory knowledge that their teammates brought and they could learn from.

In terms of knowledge contributions, the performative dynamic showed when students spoke up and acted knowledgeable about topics on which they were not necessarily experts. This strategy seemed to allow them to appear more knowledgeable and worthy contributors by sharing non-specialist knowledge, rather than exposing a lack of knowledge about a specific topic. Therefore, they ignored their own not-knowing. This ‘overselling’ of expertise occurred when students resorted to contributing non-specialist knowledge—such as popular understanding—to contribute to topics about which they lacked specialist knowledge. In the following example, S6 contributed information from a popular scientific source—a documentary—during a team meeting to make a broad sweeping statement on a topic about which she did not hold specialist, academic knowledge and could also not be expected to have this specialist knowledge considering her training background:

“Last night I watched the Seaspiracy documentary and there was the thing with the ASC brand I think for the fish, so no dolphin, fish. And that brand had extra trademarks, it was more expensive than brands that did not, so that’s also something, when things look more sustainable, they are also more expensive.”—S6 (transcript meeting 12)

In addition, we saw that students seemed to act more knowledgeable than they were when speaking with certainty and authority about methods, concepts or theories they did not fully grasp. Instead of indicating the boundaries of their knowledge, they tried to give an explanation which was unclear and incohesive. During a meeting, while the students were discussing concepts and their relationships, S5 said the following:

“Isn't it the other way around, like the law is, they put a law like: okay, we don’t allow to sell, I don’t know, plastic products, that people will yeah, I don’t know, the social norm will be more like yeah I don’t like to buy plastic, because in my country it’s not allowed and…”—S5 (meeting 12)

This example demonstrates S5 had limited understanding of concepts that she was referring to—such as laws and social norms. However, instead of indicating that this was not her expertise, she made a suggestion that was not grounded in knowledge that she holds. She also stammered searching for words, and it is hard to understand what exactly she meant.

These contributions of non-specialist knowledge may cause a false sense of understanding and lead teammates to misjudge the person’s expertise. Speaking up frequently created the impression of being a knowledgeable teammate, as S4 expressed in the following quote: “So I think that because [S3] and [S2] are more loud-mouthed, that it also seems as if they are knowledgeable”—S4 interview 3.

In terms of engaging with knowledge, we saw that students often did not ask clarification questions, even though there were plenty of ambiguities and uncertainties to resolve. As teachers we also instructed them explicitly to ask clarification questions. However, instead they often made comments or asked questions about topics they were already somewhat knowledgeable about. As such, they seemed to avoid not-knowing. The following question illustrates an example from practice of a question posed by S3 posed in meeting 2:

“How will you measure [key concept in other’s research], because I think different people will perceive it in a different way, how would you take that into account?” (S3 transcript meeting 2).

This example shows that S3 did not ask what the concept her teammate was working on meant, even though she could not know how it is conceptualized and operationalized in the other’s research. Instead, the comment was about a possible challenge in measuring this concept, asking how the teammate planned to deal with that. This kind of response exposes a tendency that we observed repeatedly and consistently to speak up by expressing showing what they do know rather than exposing what they do not know.

Taken together, we thus saw that the performative dynamic manifested as not (fully) acting as a relative expert. Rather than taking on the role of non-expert in relation to others’ knowledge bases and the lacunas in their own knowledge, the performative dynamic was characterized by expert behaviour also on these occasions.

Students behaving as experts and non-experts

To sum up, we saw that the students in our team often did not act as relative experts. Instead of taking on the role of expert by contributing their unique contributory expertise, they often contributed shared or non-specialist knowledge, or did not contribute any knowledge. In addition, instead of taking on the role of non-expert by engaging with others’ unique contributory expertise, they often engaged with shared and non-specialist knowledge. This is thus in contrast with the knowledge interactions that literature pointed at as to support effective interdisciplinary teamwork and the development of shared understanding.

We argue that the conformative and performative dynamics, being manifestations of the team not acting as relative experts, explain why the development of shared understanding was hampered in our student team. This implies the difficulty of acting as a relative expert, and the existence of forces that incline teams to act conformatively and performatively instead of acting as a relative expert. This raised the follow-up question of what shaped the team interactions towards conformative and performative dynamics and away from a network of relative experts. In the following section we discuss individual and team level processes that we observed to shape the team interactions towards conformative and performative dynamics.

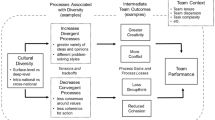

Individual and team level processes

We observed three categories of factors that shaped conformative and performative dynamics: epistemic competencies of individual team members, shared assumptions about interdisciplinary teamwork among team members, and social context. In this subsection, we describe how these three categories of factors affected teamwork and shaped its dynamics.

Individual epistemic competencies affecting team dynamics

On the individual level, we found that students demonstrated predominantly what we in our previous work (Horn et al. 2022) described as naïve behaviour. This implies they lacked competencies to contribute their own knowledge—epistemic stability—as well as competencies to engage with others’ knowledge—epistemic adaptability. We saw that these competencies, and especially lack thereof, shaped dynamics on the team level.

To begin with, students demonstrated low competencies to contribute their unique knowledge to the joint team effort, hence low epistemic stability. For instance, the students seemed to demonstrate limited grounding in their own fields and projects. They often did not fully master key concepts and methods, preventing them from bringing contributory expertise to teamwork. In the following example, S8 explained that inability to convey key concepts from her field to teammates prevented contributing relevant expertise to group discussions:

“I think I find it sometimes hard to bring the concepts that I know about across, like I know them in my mind but then trying to put them to words [...] I don’t know how to explain it.[...] when we talk about concepts and theories, I know about them [...] but then explaining it, putting it to words, and including it in the discussion, I find that really hard”—S8, interview 3.

Limited grounding in her own field inhibited bringing in unique contributory expertise. Not bringing her expertise as a possible alternative to others’ expertise, contributed to the conformative dynamic at a team level. Besides limited grounding in their fields, we also observed students generally had low confidence about their knowledge on the topic they collectively studied, which also made them less inclined to contribute their expertise. For instance, S4 expressed insufficient confidence about her knowledge on the topic, which she expressed to be due to a combination of limited knowledge as well as general insecurity:

“I’m in general quite insecure about my own abilities and knowledge. [...] And in addition to that I don’t even know what I’m doing [in my own project], let alone that I feel like I can contribute something. So, these things reinforce each other.—S4, interview 3

Moreover, students demonstrated low epistemic competencies to engage with the knowledge others contributed. Students often rigidly held onto their views and defended their choices instead of demonstrating the openness to question and potentially revise them. The following example from a conversation in meeting 12 occurred when students were discussing the mind maps they had been working on in subgroups, with questions the two subgroups posed to each other as conversation starters. S3 said the following about the discussion in her subgroup by the end of the meeting:

“And I think that many of the questions that we got [from the other group] were kind of process related, so how does one thing relate to the other. Then we tried to make that more clear, so for example there was a question about the building consensus, so it’s like a flow, you have first the building consensus, this consensus leads to market based instruments, and then examples of these market-based instruments are subsidies and environmental taxes. So it’s kind of like our flow of thinking that it is, that we tried to represent.”—transcript meeting 12

In this example we see that the question from other students did not result in S3 (and possibly her subgroup) critically questioning and potentially revising or enriching their own conceptualizations. Instead of taking the question as an invitation to reflect on their choices, they seemed to defend the choices they had made. We consider this to be indicative of limited openness, humility, curiosity, and reflectivity. Consequently, this denied them an opportunity to engage with others’ knowledge and venture into the unknown, and prevented them from making more diverse knowledge available to a collaborative effort.

Shared assumptions about teamwork

We further observed students held several assumptions about social interactions in teamwork that contributed to emergence of conformative and performative dynamics. Students explicitly mentioned repeatedly they considered disagreement to be an undesirable behavior. For example, S2 reported in week 4 she considered openness and constructiveness to be at odds with having disagreement in teamwork: “I did not experience disagreement in the group. […] everybody was very open and tried to build onto the input of the other students.”. And S1 (interview 1) revealed “I am more likely to follow someone else […] in order to keep the good peace.” Clearly she saw disagreement as a threat to the atmosphere of the team, spurring her to act in conformity with others.

To no surprise, then, students reported they sometimes did not ask critical questions, because they felt that critically questioning others was socially undesirable. For instance, S8 commented she was held back in asking others critical questions—even though she acknowledged their potential value to teamwork—because she did not want to criticize others:

“I think the problem with the questions, at least for myself, is that I don’t want to question what they did. So I think it might be hard to ask: ‘why did you do it this way?’, while asking might actually help them to realize: ‘oh, maybe it should not be like this.’ […] It's a bit like not wanting to question their work. [...] I think that maybe I experience being critical as a negative thing…”—S8 interview 3

The underlying perception seems to be that being critical about contributions of others means criticizing them personally. On top of that, they also seemed to hold the assumption that interdisciplinarity is the pursuit of similarities, rather than an exploration of differences. Besides seeming (personally) critical, students also gave other reasons that asking questions might be deemed as socially undesirable, including feeling like a burden when others needed to answer their questions and seeming unmotivated or uninterested if they did not try harder to understand by themselves.

Moreover, students’ comments suggested that they thought their team members may judge them negatively if they indicated not-knowing. In the following quote S4 explained despite no indication her teammates in this team are judgmental, she held a deeply rooted assumption others may think badly of her when she says something that seems stupid:

“The fear that you say something very stupid and that others think: you know nothing about this. It doesn’t feel unsafe in our team, but still you just want to do it right”—S4 interview 3

Discomfort with not-knowing is ingrained in our educational system: students (and for that matter veteran researchers) are assessed by their knowledge and abilities. S7 echoed the fear that follows:

“We are not taught that it is OK not to know, we always have to know things. If you don’t know, maybe you didn’t try enough. […] you have to know the answer in an exam, and if you don’t, you fail.”—S7 interview 3

Taken together, the students seem to have held assumptions about social interactions in teamwork that contributed to conformative and performative dynamics in the team.

Social context

In addition, other social and contextual factors contributed to emergence of conformative and performative team dynamics. Time pressure caused students to skip divergent processes of critically examining and questioning their approaches to quickly progress towards clear outputs—in terms of performativity—and to aim for quick agreements—in terms of conformitivity. We especially observed this tendency towards the end of the course, when deadlines started to draw close. For instance, S1 explained why she did not pay more attention to trying to understand each other and asking more questions:

“We are curious and want to know more [about each other’s projects], but currently we have too many things in their heads and do not have a lot of time and attention left”—S1 interview 2

Moreover, students indicated some of conformative and performative dynamics also found their origin in feelings of social uneasiness. Gradual development of familiarity seemed to enable and encourage contributing one’s own and engaging with others’ knowledge, thus reducing conformative and performative tendencies. In the following quote, S6 reported becoming more inclined to share knowledge—and thus to potentially act less conformatively and performatively—once team members got to know each other better:

“I think that everyone is getting more comfortable in the group, and that that makes it easier to talk to each other. At first the atmosphere was a bit more formal, and now it’s a bit more relaxed. That helps to sometimes suggest an idea, and to just see how it is received.”—S6, interview 3.

Developing this familiarity was affected by both group size and by the online setting in which the course took place. Students indicated it was somewhat harder to get to know each other and build relationships online than in offline settings (“The online setting makes it a bit more difficult, it remains a little more formal than it would be in real life”—S4, interview 3). Working in smaller subgroups, however, helped build familiarity.

Not only did group size affect the building of familiarity, our findings suggested it also directly affected conformative and performative dynamics. For instance, S2 found the team acted more conformatively and exposed fewer disagreements when conversing with the whole group of eight students as compared to smaller group engagements with only a part of the team. S2 reflected in exercise 9: “I don't think we really have disagreement but it is kind of hard with 8 people because some say more than others. It is hard to really have a conversation with everyone”. S3 also explained how being a relatively big group of eight members could cause individuals to contribute less often, because no one felt directly responsible to speak up and that they would not be held accountable for not contributing:

“We are now with eight people and that is just slightly too big a group for everyone to say something. So maybe when we split into smaller groups, [...] then it stands out when you don’t say anything. While when you are with eight, you may think that someone else will speak up anyway.”—S3, interview 3

In addition, the online setting also directly—on top of the effect through impairing the development of familiarity—affected the likelihood of students speaking up to contribute or engage with others’ knowledge. S4 explained how her insecurity to speak up in the group was accentuated by the online setting:

“With Zoom, when you say something, everyone sees your head big in their screens and all the attention is directed at you. While in real life, the threshold is lower to speak up. [...]At least I notice with myself that I’m more likely to contribute offline than online.”—S4, interview 3.

Therefore, different contextual and social factors influenced team dynamics, including time pressure, familiarity, group size, and the online setting.

An interplay of individual and team level processes

Taken together, these findings show that the conformative and performative dynamics were shaped by individuals’ epistemic competencies, shared assumptions about factors conducive to teamwork, and social context. We saw that this happened through an interplay of these individual and team level, and endogenous and exogenous factors. For instance, we saw that feeling familiar in the team helped students contribute partially developed ideas, even when their confidence was relatively low. As such, a favorable social context (familiarity) helped dealing with limited competence (low epistemic confidence) to move away from behaviour (not speaking up) fueled by assumptions (potentially being judged for saying something stupid), that would have contributed to conformative and performative dynamics that hamper knowledge integration. Oppositely, social context could also reinforce characteristics that hampered knowledge integration. For example, we observed that the online setting made students who were already insecure even less inclined to contribute, and thus reinforced the conformative dynamic.

This also shows that psychological safety and trust served as intermediate, emergent factors shaped by different team processes and contextual factors and in turn affecting the team integration behaviours and dynamics. Something similar could be said about the emergence of experienced power imbalances, which could for instance arise from (experienced) differences in knowledge and assertiveness (individual competencies), and language barriers, cultural differences, and perceived disciplinary hierarchies (social context and assumptions).

So, an interplay of individual and team level factors jointly shaped conformative and performative dynamics, through intermediate, emergent characteristics at the team level. Individual as well as team level processes reinforced dynamics if unfavorable for knowledge integration, and helped overcome the dynamics if favorable. This shows the entwinement of social and knowledge integration processes and the complexity of the mix and interplay of different factors and processes that jointly shape a team’s integrative capacity.

Discussion

To gain insight into how interactions in interdisciplinary teamwork shape knowledge integration processes, this study has reported on collaboration in a student team working on an interdisciplinary project. Based on our findings, we proposed a conceptualization of acting as a ‘relative expert’ in interdisciplinary teamwork, by acting as an expert—sharing one’s contributory expertise in such a way that it become of use to the team effort—and as a non-expert—engaging with others’ expert knowledge through modest inquiry and the attempt to understand and use their contributions. Based on our findings, we surmise that when collaborators take on this dual role of expert and non-expert, shared understanding can be built and knowledge integration can take place in interdisciplinary teamwork. Moreover, we described two dynamics that were characteristics of the collaboration in the team that we followed. Those were disruptive of the process of knowledge integration, as the collaborators often did not act as relative actors. This demonstrates that acting as a relative expert is challenging, and we saw that this was due to social and individual factors. These findings hold the promise to support others to recognize those dynamics in teams that they are active in or that they study and/or support, and to design interventions and guidance to prevent and overcome those dynamics. As such, the improved understanding of this process may contribute to improving interdisciplinary teamwork on complex sustainability issues.

The evidence we gathered indicated a combination of student competencies, social processes and assumptions, and contextual factors shaped two team dynamics that impeded knowledge integration in our team: conformative and performative dynamics. Students in our team did not engage in the cognitive struggle considered crucial for interdisciplinary knowledge integration (Pennington 2016). Neither did they embrace uncertainty and lack of consensus that are essential for interdisciplinary work (Miller 2013). As a consequence, students did not engage in joint framing of the sustainability issue on which they worked, which Oughton and Bracken (2009) judged to be necessary. Rather they reached Defila and Di Giulio’s (2017) notion of ‘agreement in an everyday sense’ (p. 332) and do not use the productive role of difference (Vilsmaier and Lang 2015). Moreover, they did not engage in mutual learning (Schwarz and Bennett 2021). As a consequence, their interdisciplinarity remained narrow and shallow, exhibiting Boix Mansilla’s (2005) conception of ‘naive interdisciplinarity’. To no surprise, the difficulty of knowledge integration is stressed throughout the literature (e.g. O’Rourke et al. 2016; Pohl et al. 2021). It should thus not be surprising that the master’s students often did not succeed in this highly challenging activity.

The conformative dynamic we observed in analyzing this team resonates with earlier findings that differences in interdisciplinary work can be experienced as too uncomfortable to address, resulting in staying in one’s comfort zone (Freeth and Caniglia 2020). Moreover, social pressure to conform and to avoid conflict, has been studied extensively in managerial and psychological research. The concept ‘groupthink’ describes the phenomenon that groups of people may tend to conform to group values and ethics in the presence of high team cohesiveness (i.e., the degree to which team members display shared social attraction, identify themselves positively with the team, and want to remain its members (Hogg and Hains 1998; Huang and Liu 2022)). Moreover, the silencing of disagreement to avoid conflict is reported in organizations (Perlow and Repenning 2009) and interdisciplinary research collaboration (Verouden et al. 2016), for instance by assuming rather than substantiating agreement, which we also saw in our team. This poses the question how constructive disagreement can be nurtured in interdisciplinary teamwork. The authors of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guide to collaboration and team science (Bennett et al. 2018), urge collaborators to be critical towards the substance of other collaborators’ contributions, but not towards the people themselves. Strober (2011), however, argues that such a distinction between cognitive and affective processes is an over-simplification that does not do justice to the fact that interdisciplinary work is “filled with affective issues, including disciplinary identity and uneasiness with presenting work to those outside one’s “comfort zone”” (Strober 2011, p. 70). She thereby argues that affective conflict is inherent to interdisciplinary teamwork. This, therefore, urges the development of further understanding of how to nurture constructive conflict in interdisciplinary teamwork. Besides aversion to conflict, the conformative dynamic that we observed is also in line with findings that collaborators tend to conform, because familiar contributions are received as more useful and the collaborators who make those contributions are perceived as more knowledgeable (Stewart and Stasser 1995). Contributing knowledge that is already shared is thus rewarded through social acceptation and appreciation.

Furthermore, we found the performative dynamic negatively affected knowledge integration processes, because collaborators applied their expertise to contexts they were not knowledgeable about and had fixed views, causing others to overestimate their expertise, and as a consequence to overly rely on it. As such, they acted as experts when their knowledge did not justify that role. Keestra (2017) cautioned against these disadvantages. He proposed development of metacognition as a possible way to mitigate these disadvantages. Studying how students’ metacognition can be trained and how that strategy affects the performative team dynamic may thus be a promising avenue for future research. Our findings on performative dynamics and behaviours parallels Edmondson’s (2002) and Decuyper et al.’s (2010) descriptions of hierarchical teams with low psychological safety. Collaborators were less likely to ask questions, be critical, and admit mistakes when experiencing fear of being perceived as ignorant, incompetent, or disruptive. Our findings also affirmed psychological safety played a role in admitting being wrong or not-knowing as well as uncertain. However, at the same time, our data yielded examples of students who reported feeling safe, but also engaged in performative avoidance of risk aversive behaviours, indicating that the performative dynamics was not just caused by low psychological safety. Hence, our findings suggest this behaviour is a natural tendency that can be either overcome by high psychological safety or exacerbated by a sense of not being safe. Additional research is needed, however, to fathom how psychological safety, innate social tendencies, and competencies jointly shape performative behavioural dynamics.

The three categories of factors that jointly shape the process of integrating team knowledge—individual competencies, shared assumptions, and social and contextual factors—provide three avenues to stimulate, support, and/or train interdisciplinary integration in teams working on complex sustainability issues. First, to deal with assumptions about what interdisciplinary teamwork entails, such as a quest for similarities and a linear process towards a predefined goal, collaborators should be explicitly instructed about interdisciplinarity and teamwork. Second, to support teams in educational and research contexts in collaboration and integration, educators and project managers can provide a favorable context to remove barriers. Both our study and earlier findings by Salazar et al. (2012) and Boix Mansilla et al. (2016) emphasize importance of providing ample time, nurturing psychological safety, and considering team composition in terms of group size and compatibility in supporting interdisciplinary teamwork and, per Boix Mansilla et al. (2016) and Defila and Di Guilio (2017), educators and project leaders.

Moreover, the likelihood that collaborators share unshared knowledge—and thus overcome the conformative dynamic—has been reported to increase with time (Godemann 2008). Although time pressure is likely to affect any interdisciplinary project, this is likely to be accentuated even further by the prominence of extrinsic motivators, such as course deliverables, graded assignments and credits in the educational context. Those are likely to create a push towards more instrumental approaches (Kahu 2013), which in the context of interdisciplinarity may come at the expense of more critical and integrative interdisciplinarity (Bradshaw 2021). Although this is likely to weigh less heavily in our iCSL2 course, due to its voluntary and extracurricular nature, this is a tension that is important to consider when designing and implementing interdisciplinary education. Third, the finding that low epistemic competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration contribute to conformative and performative team dynamics implies that training these competencies can benefit teamwork. Because development of competencies relies on double- and triple-loop learning (Argyris and Schön 1978), experience and reflection can be expected to play key roles (Kolb and Kolb 2009). Future research could also provide more detailed insight into how to develop epistemic competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration.

Methodological considerations

The fact we followed one team of eight students in a 5-month course in detail allowed us to collect rich micro-level data about their collaboration process. The combination of observations, recordings of team meetings, interviews, and written reflections yielded insights into both individual and team processes based on students’ behaviour and self-reports. The combined roles of researchers and teachers may have affected data collection, considering the power relationship between student and teacher. To minimize this, we have explicitly split and communicated the division of tasks in which the first author was the primary researcher who collected fieldnotes and interview data, without being involved in assessment, and the second author was the primary teacher.

And also in the process of data analysis and interpretation, the dual role of teacher and researcher in this action research project should be acknowledged. Our findings heavily rely on our interpretations as researchers, combining insights from our first-hand observations and interview and reflection data. We aimed to capture stable, recurrent patterns that presented themselves over a longer period of time and thus only report findings that we observed repeatedly. To ensure the reliability of our findings, we further relied on data, methodological, and researcher triangulation (Flick 1992; Harvey and MacDonald 1993; Golafshani 2003; Peräkylä 2011). We combined different data collection methods—interviews, reflections, observations—data from different perspectives—student self-report, peer-reports and teacher observations—and had at least weekly joint reflections between the members of the research team (first and second author), and several joint discussions with a researcher not otherwise involved in the project.

The micro-level approach of following one team intensively means we collected data on a small sample with only eight students. However, we deemed this in-depth approach appropriate to achieve our goal of understanding the emergence of knowledge integration processes in interdisciplinary teamwork. The consequent small sample size provided us with insufficient information about how other forms of diversity within the team—such as national cultures and English proficiency—affected teamwork. Follow-up research is needed to shed light on how teamwork is shaped when other factors are added to the mix.

Furthermore, the study of this single team meant that we only learned about knowledge integration in the predominantly naive team, so did not gain insight into how knowledge integration comes about and can be supported in teams with different combinations of behaviours, competencies, sizes, and durations. As a consequence of the limited knowledge integration capacity in this team, we cannot draw definitive conclusions about how successful knowledge integration emerges in interdisciplinary teamwork. The challenges and corresponding obstacles that we observed and identified do help us to understand a little better how team level knowledge integration processes arise and affect team performance (O’Malley 2013). This study proposes new understanding that can be the starting point of additional analyses of knowledge integration processes in interdisciplinary teamwork.

The small sample size of our study does not allow for statistical generalization. Rather, we have provided thick descriptions that allow readers to identify how our findings can be translated to their contexts to ensure transferability (Houghton et al. 2013; Tight 2022). Moreover, the key concepts and constructs that we identified could be used as a basis for the development of testable propositions for assessing the process of knowledge integration through the emergence of three parallel and iterative processes.

Conclusions

To draw conclusions from this case study and related findings, we saw that the interplay of individual level competencies and team processes caused the team to behave conformatively and performatively. This combination of dynamics was disruptive for interdisciplinary collaboration and integration processes, because it prevented students from acting as relative experts. Acting as a relative expert means taking on the role of expert—bringing their knowledge, explaining, clearly indicating its boundaries and (un-)certainties—in relation to their own contributory expertise, while at the same time also taking on the role of non-expert—engaging with others’ knowledge by curiously, critically and modestly questioning—in relation to others’ contributory expertise. Consequently, the process of interdisciplinary collaboration remained narrow and shallow. We thus surmise that these tendencies must be overcome to enable knowledge integration that fulfills the full potential of interdisciplinary teamwork.

Our findings can inform interventions to support interdisciplinary collaboration and integration. The two dynamics we described serve as an analytical and practical lens through which teachers and project leaders can recognize dynamics that may be affecting teams’ knowledge integration processes. Moreover, they provide insights into how these dynamics can be counteracted by challenging teams’ assumptions about interdisciplinarity and knowledge integration, training epistemic competencies for interdisciplinary teamwork and knowledge integration processes, and nurturing a teamwork environment that is safe and supportive of knowledge integration processes. As such, our findings hold the promise to further understanding as well as functioning of interdisciplinary teamwork to address complex sustainability issues.

Key avenues for future research that we identified include understanding psychosocial mechanisms underlying performative behaviour and achieving a more detailed understanding of how development of epistemic competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration can be supported. When these processes are better understood, it will be possible to further open up the black box of knowledge integration.

Data availability

Raw data for this study are not publicly available to preserve individuals’ privacy, considering the small scale and personal nature of the case study.

Notes

As the course name suggests, the iCSL2 course is both interdisciplinary—through the teamwork among students from diverse disciplinary backgrounds towards a joint, integrated product—and transdisciplinary—through the collaboration between university students and community partners. However, the team that we considered in this study only engaged in interdisciplinary collaboration and integration, without collaboration between students and non-academic partners. For an insight into examples of transdisciplinary work in the iCSL courses, we refer readers to Tijsma et al. (2023).

References

Argyris AY, Schön DA (1978) organizational learning: a theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co, Reading

Bammer G, O’Rourke M, O’Connell D et al (2020) Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun 6:5. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0380-0

Bath C (2009) When does the action start and finish? Making the case for an ethnographic action research in educational research. Educ Act Res 17:213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790902914183

Bennett LM, Gadlin H, Marchand C (2018) Collaboration team science: field guide

Boix Mansilla VB (2005) Assessing student work at disciplinary crossroads. Change Mag High Learn 37:14–21. https://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.37.1.14-21

Boix Mansilla VB (2017) Interdisciplinary learning: a cognitive-epistemological Foundation. In: Frodeman R, Klein JT, Pacheco RCS (eds) The Oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 261–275

Boix Mansilla V, Lamont M, Sato K (2016) Shared cognitive–emotional–interactional platforms: markers and conditions for successful interdisciplinary collaborations. Sci Technol Hum Values 41:571–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915614103

Bradshaw AC (2021) Reframing interdisciplinarity toward equity and inclusion. In: Intersections across disciplines. Springer, Cham, pp 197–208

Clark WC, van Kerkhoff L, Lebel L, Gallopin GC (2016) Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:4570–4578. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601266113

Collins HM, Evans R (2002) The third wave of science studies: Studies of expertise and experience. Soc Stud Sci 32(2):235–296

Collins HM, Evans R (2007) Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Cronin MA, Weingart LR (2007) Representational gaps, information processing, and conflict in functionally diverse teams. Acad Manage Rev 32:761–773. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275511

Crowley S, O’Rourke M (2020) Communication failure and cross-disciplinary research. In: O’Rourke M, Orzack SH, Hubbs G (eds) The power of cross-disciplinary practice. The toolbox dialogue initiative. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 1–16

Dahlin KB, Weingart LR, Hinds PJ (2005) Team diversity and information use. Acad Manage J 48:1107–1123. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.19573112

Decuyper S, Dochy F, Van den Bossche P (2010) Grasping the dynamic complexity of team learning: an integrative model for effective team learning in organisations. Educ Res Rev 5:111–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.02.002

Defila R, Di Giulio A (2017) Managing consensus in inter- and transdisciplinary teams: tasks and expertise. In: Frodeman R, Klein JT, Pacheco RCS (eds) The oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 332–337

Edmondson AC (2002) The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: a group-level perspective. Organ Sci 13:128–146. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.2.128.530

Eigenbrode SD, O’Rourke M, Wulfhorst JD et al (2007) Employing philosophical dialogue in collaborative science. Bioscience 57:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1641/B570109

Fiore SM (2008) Interdisciplinarity as teamwork: how the science of teams can inform team science. Small Group Res 39:251–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408317797

Flick U (1992) Triangulation revisited: strategy of validation or alternative? J Theory Soc Behav 22(2):175–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1992.tb00215.x

Freeth R, Caniglia G (2020) Learning to collaborate while collaborating: advancing interdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustain Sci 15:247–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00701-z

Godemann J (2008) Knowledge integration: a key challenge for transdisciplinary cooperation. Environ Educ Res 14:625–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802469188

Golafshani N (2003). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8, pp 597–606. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2003.1870

Grin J, Van De Graaf H (1996) Implementation as communicative action: an interpretive understanding of interactions between policy actors and target groups. Policy Sci 29:291–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138406

Harvey L, MacDonald M (1993) Doing sociology: a practical introduction. Red Globe Press, New York

Hogg MA, Hains SC (1998) Friendship and group identification: a new look at the role of cohesiveness in groupthink. Eur J Soc Psychol 28(3):323–341

Holm P, Goodsite ME, Cloetingh S et al (2013) Collaboration between the natural, social and human sciences in global change research. Environ Sci Policy 28:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.010

Horn A, Urias E, Zweekhorst MBM (2022) Epistemic stability and epistemic adaptability: interdisciplinary knowledge integration competencies for complex sustainability issues. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01113-2

Houghton C, Casey D, Shaw D, Murphy K (2013) Rigour in qualitative case-study research. Nurse Res 20:12–17. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326

Huang CY, Liu YC (2022) Influence of need for cognition and psychological safety climate on information elaboration and team creativity. Eur J Work Organ Psy 31(1):102–116

IPCC (2022) Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Jerneck A, Olsson L, Ness B et al (2011) Structuring sustainability science. Sustain Sci 6:69–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-010-0117-x

Kahu ER (2013) Framing student engagement in higher education. Stud High Educ 38(5):758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

Keestra M (2017) Metacognition and reflection by interdisciplinary experts: insights from cognitive science and philosophy. Issues Interdiscip Stud, pp 121–169

Kjellberg P, O’Rourke M, O’Connor-Gómez D (2018) Interdisciplinarity and the undisciplined student: lessons from the Whittier Scholars Program. Issues Interdiscip Stud 36:34–65

Klein JT (2017) Typologies of interdisciplinarity: the boundary work of definition. In: Frodeman R, Klein JT, Pacheco RCS (eds) Oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 21–34

Knorr-Cetina K (1999) Epistemic cultures: how the sciences make knowledge. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kolb AY, Kolb DA (2009) Experiential learning theory: a dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development. The SAGE handbook of management learning, education and development. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp 42–68

Kovács G, Spens KM (2005) Abductive reasoning in logistics research. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 35:132–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030510590318

Le Gall V, Langley A (2015). An abductive approach to investigating trust development in strategic alliances. In: Handbook of research methods on trust. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp 36–45

Lotrecchiano GR, Mallinson TR, Leblanc-Beaudoin T et al (2016) Individual motivation and threat indicators of collaboration readiness in scientific knowledge producing teams: a scoping review and domain analysis. Heliyon 2:e00105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00105

Lotrecchiano GR, DiazGranados D, Sprecher J et al (2020) Individual and team competencies in translational teams. J Clin Transl Sci 5:e72. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.551

McArthur JW, Sachs J (2009) Needed: a new generation of problem solvers. Chronicle 55:A64

Miller TR (2013) Constructing sustainability science: emerging perspectives and research trajectories. Sustain Sci 8:279–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-012-0180-6

Misra S, Stokols D, Cheng L (2015) The transdisciplinary orientation scale: factor structure and relation to the integrative quality and scope of scientific publications. J Transl Med Epidemiol 3:1042

Morse WC, Nielsen-Pincus M, Force JE, Wulfhorst JD (2007) Bridges and barriers to developing and conducting interdisciplinary graduate-student team research. Ecol Soc 12:art8. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02082-120208

O’Malley MA (2013) When integration fails: prokaryote phylogeny and the tree of life. Stud Hist Philos Sci Part C Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 44(4):551–562

O’Rourke M (2017) Comparing methods for cross-disciplinary research, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 276–290

O’Rourke M, Crowley S, Gonnerman C (2016) On the nature of cross-disciplinary integration: a philosophical framework. Stud Hist Philos Sci Part C Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 56:62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2015.10.003

O’Rourke M, Crowley S, Laursen B, et al (2019) Disciplinary diversity in teams: integrative approaches from unidisciplinarity to transdisciplinarity. In: Hall KL, Vogel AL, Croyle RT (eds) Strategies for team science success: handbook of evidence-based principles for cross-disciplinary science and practical lessons learned from health researchers, pp 21–46

Oughton E, Bracken L (2009) Interdisciplinary research: framing and reframing. Area 41:385–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00903.x

Parker J (2010) Competencies for interdisciplinarity in higher education. Int J Sustain High Educ 11:325–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371011077559

Pennington D (2016) A conceptual model for knowledge integration in interdisciplinary teams: orchestrating individual learning and group processes. J Environ Stud Sci 6:300–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0354-5

Pennington D, Vincent S, Gosselin D, Thompson K (2021) Learning across disciplines in socio-environmental problem framing. Socio-Environ Syst Model 3:17895–17895

Peräkylä A (2011) Validity in research on naturally occurring social interaction. In: Silverman D (ed) Qualitative research, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications Ltd., pp 366–382

Perlow LA, Repenning NP (2009) The dynamics of silencing conflict. Res Organ Behav 29:195–223

Pohl C, Klein JT, Hoffmann S et al (2021) Conceptualising transdisciplinary integration as a multidimensional interactive process. Environ Sci Policy 118:18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.12.005

Regeer BJ, Bunders JFG (2009) A transdisciplinary approach to complex societal issues. RMCO, Den Haag

Rylance R (2015) Grant giving: Global funders to focus on interdisciplinarity. Nature 525:313–315. https://doi.org/10.1038/525313a

Ryser L, Halseth G, Thien D (2009) Strategies and intervening factors influencing student social interaction and experiential learning in an interdisciplinary research team. Res High Educ 50:248–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9118-3

Salazar MR, Lant TK, Fiore SM, Salas E (2012) Facilitating innovation in diverse science teams through integrative capacity. Small Group Res 43:527–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412453622

Schwarz RM, Bennett LM (2021) Team effectiveness model for science (TEMS): using a mutual learning shared mindset to design, develop, and sustain science teams. J Clin Transl Sci 5:e157. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2021.824

Souto PCDN (2015) Creating knowledge with and from the difference: the required dialogicality and dialogical competencies. In: Rev Adm Innov—RAI 12, pp 60. https://doi.org/10.11606/rai.v12i2.100333

Stephens N, Stephens P (2021) Interdisciplinary projects as an expert-network: analysing team work across biological and physical sciences. Sci Technol Stud 34(4):56–73

Stewart DD, Stasser G (1995) Expert role assignment and information sampling during collective recall and decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol 69:619–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.619

Strober MH (2006) Habits of the mind: challenges for multidisciplinary engagement. Soc Epistemol 20:315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691720600847324

Strober MH (2011) Interdisciplinary conversations: challenging habits of thought. Stanford University Press, Stanford