Abstract

Global sustainability challenges transcend disciplines and, therefore, demand interdisciplinary approaches that are characterized by cross-disciplinary collaboration and integration across disciplines. In accordance with this need for interdisciplinary approaches, sustainability professionals have been reported to require interdisciplinary competencies. Although the necessity of interdisciplinary competencies is generally agreed upon, and there has been extensive research to understand competencies for interdisciplinarity, there is still no comprehensive understanding of how individual competencies shape the ability to integrate knowledge across disciplines. Therefore, based on empirical research and literature review, we propose a novel framework to understand competencies for interdisciplinarity. The empirical data were collected through written reflection and interviews with 19 students in the context of an interdisciplinary master’s course. We describe four typical behaviours—naïve, assertive, accommodating, and integrative. Based on these behavioural typologies, we define two sets of competencies that collaborators require to engage in interdisciplinary knowledge integration: Epistemic Stability (ES) and Epistemic Adaptability (EA). ES competencies are the competencies to contribute one’s own academic knowledge, such as theoretical and methodological grounding in one’s own field and confidence, and EA competencies are the competencies to engage with academic knowledge contributed by others, such as curiosity, openness and communicative skills. Our findings show that interdisciplinary knowledge integration requires ES and EA competencies. Our framework for interdisciplinary competencies offers insights for revising and designing more interventions to prepare (future) professionals for interdisciplinary work on sustainability issues, providing insights on criteria for assessment, management, and training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Society faces an increasing number of complex sustainability challenges, such as climate change, pollution, social segregation, and inequality in wealth, health, and well-being—all of which transcend academic disciplines (Holm et al. 2013; Jerneck et al. 2011; McArthur and Sachs 2009). Due to their complex and multifaceted nature, these issues demand knowledge that goes beyond what individual (disciplinary) researchers and practitioners hold (Ryser et al. 2009). Therefore, they require collaboration between professionals from different academic fields: cross-disciplinary teamwork (Fiore 2008). Cross-disciplinary collaboration takes multiple forms such as multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity. To address real-world sustainability issues effectively and holistically, cross-disciplinary teamwork should be in service to practice, meaning that societal needs inform disciplinary representation and collaboration as to achieve more relevant outcomes (Clark et al. 2016; Donaldson et al. 2010; Miller 2013; Robinson 2008). To achieve this, knowledge should not merely be combined through accumulation, mechanistic pooling, and juxtaposition as is the case in multidisciplinarity (Klein 2017). But rather, new knowledge should be generated to create new, more extensive, and more relevant understanding that goes beyond what any individual disciplinary perspective can contribute (Klein 2017; Mansilla 2005). This knowledge integration distinguishes interdisciplinarity from multidisciplinarity (Klein 2017).

Interdisciplinary knowledge integration depends on the representation of diverse knowledge—in terms of theories, approaches, and methods—to address sustainability issues holistically, as diversity in cross-disciplinary teams allows for more comprehensive understanding (Klein 2017; Drach-Zahavy and Somech 2001). This requires harnessing differences to use the diversity of knowledge as a resource to cross-disciplinary work (Bammer 2013). Yet, at the same time, this diversity also poses its main challenge (Cronin and Weingart 2007; Luan et al. 2016; Majchrzak et al. 2012). This means that interdisciplinary knowledge integration poses an inherent trade-off: the greater the disciplinary diversity in the team (including the number of disciplines involved, distribution of disciplinary perspectives across team members, and degree of dissimilarity among the disciplines), the more promising it is in terms of innovation and comprehensiveness to address complex issues, but also the more challenging it is to overcome the incommensurabilities (Crowley and O’Rourke 2020; Salazar et al. 2012). Researchers are socialized in their respective fields and research communities and tend to hold disparate science views, characterized by beliefs and assumptions that differ epistemologically—i.e., in terms of how to create knowledge and how to support knowledge claims—and ontologically—i.e., in terms of how research represents the inherent nature of the world (Knorr Cetina 1999; Eigenbrode et al. 2007; MacLeod 2018; Moon et al. 2021). Moreover, fields also differ in their practices, and styles of thinking, presenting, and questioning, which are likely to cause tensions and disagreements in interdisciplinary teamwork and so hamper integration (Strober 2006; Morse et al. 2007; MacLeod 2018).

Navigating these disciplinary differences requires competencies that researchers and practitioners do not self-evidently possess (Brown et al. 2015; Cairns et al. 2020; Larson et al. 2011; Salas et al. 2018; Salgado et al. 2018; Strober 2006). Without training in interdisciplinarity, cross-disciplinary collaboration may be devoid of disciplinary perspectives (Mansilla et al. 2009), or remain limited to monodisciplinary or multidisciplinary processes and outcomes and thus lack the necessary integration to address sustainability issues holistically (Mansilla et al. 2009; Richter and Paretti 2009; Roy et al. 2020). Equipping (future) professionals for interdisciplinary work thus requires explicit training in interdisciplinary competencies (Di Giulio and Defila 2017; Fiore et al. 2019; Godemann 2006; Roy et al. 2020). As the university trains future professionals, higher education plays a key role in educating responsible leaders, managers and change agents for the transition towards a more sustainable society (Godemann 2006; Hesselbarth and Schaltegger 2014; Garcia et al. 2006; Mossman 2018; Osiemo 2012; Palma et al. 2011). In response to the growing awareness of this need for competence-building, higher education is paying increasing attention to competency-based training to prepare (future) professionals to address sustainability holistically (Ashby and Exter 2019; Barth et al. 2007; Brundiers et al. 2021; Parker 2010). But although interdisciplinary competencies are acknowledged as essential to sustainability work and learning (Brundiers et al. 2021; Vajaradul et al. 2021; Wiek et al. 2011), they remain poorly understood. For instance, some authors list ‘interdisciplinary competency’ as one of many competencies necessary for sustainability work (Barth et al. 2007), which seems to suggest that it is a single thing, whereas others argue that competence in interdisciplinarity requires a vast array of different competencies that need to be further unpacked to make sufficient sense of them to inform the design of training and education that targets these competencies (Parker 2010). A wealth of literature lists interdisciplinary competencies, and provides insight into specific knowledge, skills and attitudes that are necessary for interdisciplinary teamwork (e.g., Guimarães et al. 2019; Nash et al. 2003; Nurius and Kemp 2019). But the literature does not offer much insight into how different competencies relate to each other and collectively shape the competence to engage in interdisciplinary knowledge integration (Parker 2010). Designing and implementing training with the explicit intention to build interdisciplinary competencies to address sustainability issues holistically in cross-disciplinary teams requires that these competencies are better understood.

In this paper, we aim to break new ground in understanding competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration by providing insight into typical behaviours of individuals in the context of cross-disciplinary collaboration and by offering a new conceptualization of the competencies interdisciplinary knowledge integration requires. We further this under-theorized field by answering the question of how competencies shape individuals’ ability to engage in interdisciplinary knowledge integration, which is the defining characteristic of interdisciplinary teamwork (Klein 2017). To do so, we combine insights from literature with empirical findings in the context of an interdisciplinary master’s course. In the context of this course, we identified four typical behaviours which are indicative of two defining sets of competencies required for interdisciplinary knowledge integration. Together, these behaviours and corresponding competencies provide a framework to gain insights into how competencies shape interdisciplinary teamwork. These insights are relevant to educators, researchers, and practitioners, offering criteria for assessment, management and intervention in developing training in competencies for interdisciplinarity.

Materials and methods

To build onto knowledge and generate new theoretical insights into how competencies shape individual ability to engage in interdisciplinary teamwork for knowledge integration in sustainability, we applied an exploratory research design based on abductive reasoning. This approach involved a continuous process of moving back and forth between data and theory to produce a new framework (Kovács and Spens 2005; Van Breda and Swilling 2019). This iterative process is further explained in the data analysis section below. Such an in-depth approach makes it possible to richly describe and understand individual behaviour and competencies and how these shape knowledge integration in cross-disciplinary teamwork.

To understand how students’ behaviours and competencies shaped interdisciplinary knowledge integration, we analysed the students’ behaviours through observations and their reflections on their own and their peers’ behaviours through written reflection exercises and interviews. Although we examined their behaviour in the context of an interdisciplinary course in which they collaborated in cross-disciplinary teams, the unit of analysis is thus the individual student—we describe their behaviour and corresponding competencies in the context of cross-disciplinary collaboration. For the purpose of this study, we operationalized interdisciplinary knowledge integration as the process of building shared understanding in which the knowledge contributed by different individuals from different academic backgrounds is represented and related to each other, and new meaning emerges that none of the people held prior to the interaction (Klein 2017; O’Rourke et al. 2016). In studying the students’ behaviours and corresponding competencies, we did not focus on the development of competencies that they demonstrated throughout the course. Although we observed that their behaviours were relatively stable throughout the course—in the end, the scope of an eight-week course is limited—we did observe that students could behave differently at different moments, likely due to contextual factors and learning. In our analysis, we focused on describing different relatively stable patterns of behaviour in different students and at different instances to understand the diversity of behaviour exhibited, rather than the learning that took place in our student cohort. As such, we do not zoom in on changes in behaviour over time, but rather consider the observations in this relatively short course as a snapshot of their behaviour.

Study design and context

In abductive studies, it is critical to select a research setting where the phenomenon examined is highly salient, to ensure sufficiently detailed and rich data collection on different dimensions of the underlying phenomenon (Le Gall and Langley 2015). We chose the course “Interdisciplinary Community Service Learning: Defining Challenges in a Multi-Stakeholder Context” (iCSL) at the VU Amsterdam in the Netherlands for this study. As this course focuses on familiarizing students with interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge integration, it provides an excellent setting to study student competencies in interdisciplinary knowledge integration prior to receiving explicit training in these competencies. In the course, students collaborated in two cross-disciplinary teams (one of 7 and one of 12 students) on a joint project to describe a complex sustainability issue (such as waste management and inclusive technologies for health and well-being) from different academic as well as non-academic perspectives. One of the learning goals of the course is for students to become familiar with, and gain practical experience in, interdisciplinary research. Several choices were made in designing the course to support interdisciplinary collaboration and learning. To stimulate an ongoing conversation among students, all meetings centred around interactive exercises that took place in smaller subgroups of three to four students, which included mind-mapping assignments, group reflections, and an interdisciplinary journal club in which the students read and discussed papers from each other’s fields. As neither theory nor practice would be enough by themselves to train students in interdisciplinarity (Di Giulio and Defila 2017), the course included weekly written reflection exercises to further enhance interdisciplinary learning. The course requires 84 h of coursework, spread out over 8 weeks, which included weekly 2-h meetings, online preparation, and project work.

Students from any master’s programme at this university could enroll in the course, and students were actively recruited to guarantee a diverse and balanced student cohort. In total, 19 students completed the course. They were from 12 different master’s programmes, representing six of the nine faculties at the VU Amsterdam: science (n = 8), humanities (n = 5), business and economics (n = 3), medicine (n = 1), social sciences (n = 1), and religion and theology (n = 1). To ensure the anonymity of students involved in the courses we refer to the students’ study backgrounds only in broad categories: health and life sciences (n = 2); exact sciences (n = 2); management studies (n = 3), social sciences (n = 2), humanities (n = 4), and interdisciplinary programmes (n = 6). The category of interdisciplinary programmes was added, because not all master’s programmes fit into a single category, and because it was found relevant to the findings that some students are also explicitly trained for interdisciplinarity in their own master’s programme. Defining the students’ backgrounds in these broad categories enabled us to distinguish to some extent between the different disciplinary perspectives of the students and the extent of interdisciplinary training they received prior to the iCSL course. It is, however, important to note that even within these categories we observed substantial diversity, such as students with more or less specialized prior education, and different breadth of the interdisciplinary programs. It should be noted that the programmes that students are enrolled in do not necessarily map directly onto disciplines, and disciplines are not straightforward categories themselves to begin with (Klein 1983). All respondents are referred to by randomized numbers and as women, although the cohort consisted of ten female and nine male students.

Data collection

To understand competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration, in this study, we collected data from different sources to capture student knowledge integration behaviour, and to triangulate between sources and perspectives. It is important to note that the data collected was not aimed at assessing the mastery of a given set of competencies. Rather, we set out to understand how competencies shape interdisciplinary knowledge integration. We defined competencies as repertoires of capabilities, activities, processes and responses that enable individuals to meet the demands for interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge integration (Kurz and Bartram 2002). This definition is highly outcome-focused, defining competencies as a function of the success in demonstrating the behaviour that a situation demands (Heinsman et al. 2007). As such, behaviour can be considered a direct derivative of competencies and thus a reliable indicator of them (Heinsman et al. 2007). Therefore, we analysed students’ competencies for interdisciplinarity through their behaviour in the interdisciplinary course and collected data about their behaviour through observations (by staff) and student reflections (oral and written) about their own and others’ behaviour.

As this study was conducted in the context of a university course, learning activities and data collection were closely interwoven. For example, we analysed written student reflection exercises, conducted interviews that functioned as data collection as well as oral reflection exercises, and made observations during the course meetings. Consequently, we as authors also had multiple roles, as we co-designed the course (AH, MZ), attended classes (AH, MZ), were a point of contact for students (AH), and conducted the oral reflection sessions (AH). This gave us very rich insights into the students’ experiences, from their comments and feedback at any moment during the course, as well as from our own direct experience. Moreover, this allowed us to triangulate between self-report in their reflections and behaviour that we observed in class. It should, however, be noted that the close connection between research and education and the overlapping roles of researcher and educator could also have affected the students’ behaviour. We did not get signals of students acting more socially or in more pedagogically desirable ways, and we did not observe any differences in behaviour in the absence of teaching staff (as reported by students about each other) compared to when teaching staff were present; however, these cannot be ruled out and their possibility should be taken into consideration in making sense of the data in this study. Student participation in the study was voluntary and students could also participate in the course without participating in the study. All students who participated in the study provided written informed consent about the collection of research data and could discontinue their participation in the study at any time, without consequences for taking the course. It is worth mentioning that although participation in the study was voluntary, all students who took the course also opted in on participating in the study, and none withdrew their consent for the use of their data. As such, the data analyzed and reported on in this study represent the full student cohort of the course.

Reflection exercises

As part of the course, the students completed weekly online written reflection exercises. Each week, the reflection exercise consisted of a week-specific question, related to the week’s course content, and a general question about the students’ learning in that week of the course. The reflection exercises were completed in English.

Interviews

The oral reflection sessions between students and first author (AH) that took place in weeks five and six of the course were recorded as research data. In these semi-structured interviews, we aimed to gain insight into the students’ perspectives about interdisciplinarity, their own (disciplinary) background, and the interactions with students from other backgrounds. We prepared each interview based on the student’s completed written reflection exercises. Each interview lasted for approximately 1 h. To allow students to best express themselves, we conducted the interviews in Dutch when this was the student’s mother tongue (n = 11), and otherwise in English (n = 8). We audio-recorded the interviews and transcribed them verbatim.

Observations

The first author (AH) attended all course meetings and kept a reflective journal of her observations during the meetings. Predefined topics about disciplinary collaboration (disciplinary differences, knowledge exchange, and integration) guided her reflections, complemented by open observations. Moreover, she gathered insights from other staff members through conversations which informed this study indirectly.

Data analysis

In line with the theory-building approach and aim of this study, we did not base our analysis on a preconceived conceptual framework. Instead, we set out to develop a novel framework to contribute to the under-theorized topic of understanding interdisciplinary competencies. We followed an abductive reasoning approach, in which we analysed theory and empirical data through recursive iteration and continuous comparison (Le Gall and Langley 2015; Ridder 2017; Van Breda and Swilling 2019). In contrast to purely inductive approaches, we started with pre-existing conceptual ideas from substantive literature on interdisciplinary collaboration. In this literature, a commonly described obstacle to interdisciplinary knowledge integration is the lack of interdisciplinary competencies, represented by the ‘disciplinary expert’ who dominates discussions and asserts the primacy of their own discipline when exposed to experts from other fields in cross-disciplinary teams. (Brown et al. 2015; Crowley and O’Rourke 2020; Morse et al. 2007; Richter and Paretti 2009; Strober 2006). Thus, the ability to engage in interdisciplinary knowledge integration is commonly reported to be constrained by the absence of competencies necessary to understand and appreciate norms, theories, approaches and breakthroughs from other disciplines (Brown et al. 2015).

Based on these reports, we expected to observe this behaviour among our students. Although we indeed observed this type of behaviour in our student cohort, we also observed other behavioural patterns that we had not anticipated. We were particularly puzzled by the observation that some students held (overly) optimistic views of interdisciplinarity, were unaware of disciplinary differences, and were hardly involved in the content of the joint project. For this type of student, enhanced understanding and appreciation of other disciplines would not suffice to succeed in knowledge integration. As this ‘type’ does not fit into the general rule of our initial theorizations, we dove into the literature on competencies for interdisciplinary collaboration to construct plausible explanations to explain and better understand this type of student through an iterative process of theory matching. Thus, insights from the data guided further exploration of literature to refine and further develop the understanding of the behavioural typologies, including the identification of other patterns that did not fit into them. From this iteration between literature and data, ‘sensitizing concepts’ emerged. These concepts helped us identify unexplored connections between constructs from existing literature (e.g., T-shaped researchers (McIntosh and Taylor 2013), epistemic agility (Haider et al. 2018), methodological groundedness (Haider et al. 2018), epistemic humility (Gardiner 2020)), giving us directions for further analysis of the data in order to understand and explain the behavioural patterns that we observed. We repeated this iteration between the data, emergent concepts and relevant literature several times until definitive, empirically grounded concepts emerged that were also applied throughout the analysis of the empirical data. These concepts provide the basis for the conceptual framework of integrative competencies we present in the results section.

Results

In this section, we present the results of our study. We start by describing four typical and within-student consistent patterns of behaviour that we observed among students in our course: naïve, assertive, accommodating, and integrative behaviours. We describe how these typical behaviours manifest and how they affect team processes and knowledge integration. We illustrate these behavioural patterns through the use of examples from individual students in particular interaction, which are representative of the consistent patterns that we observed. As competencies are defined by the ability to successfully demonstrate behaviour (Heinsman et al. 2007), we inferred which competencies these behaviours indicate. Then, we present a novel conceptualization of the competencies necessary for interdisciplinary knowledge integration. In our framework, we distinguish between two sets of competencies: Epistemic Stability (ES) and Epistemic Adaptability (EA). ES competencies allow collaborators to contribute their own unique knowledge to a collaboration. EA competencies, on the other hand, allow collaborators to engage with the knowledge contributed by others. Assertive behaviour is the result of high ES and low EA competency, whereas accommodating behaviour is the result of low ES and high EA. We show that interdisciplinary collaboration requires ES and EA competencies. We conclude the results section with more detailed definitions of these competency sets, including an overview of the competencies within each category.

Naïve

First of all, we observed behaviour that we call ‘naïve’. When we started our research to understand competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration, the observation of this behaviour among our students surprised us. A wealth of literature stresses how challenging interdisciplinary work is and how it potentially results in tensions and conflicts (e.g., Brown et al. 2015; Crowley and O’Rourke 2020; Morse et al. 2007; Richter and Paretti 2009; Strober 2006). But on many occasions, our students were actually very optimistic about interdisciplinary collaboration and reported that they did not foresee or encounter many challenges. For instance, they did not get into conflict and did not experience difficulties in dealing with disciplinary divides. When we set out to understand this behaviour, we observed that naïve behaviour was characterized by only contributing to the joint work through common knowledge, which prevented conflict, but also caused the discussions and products to remain superficial. Moreover, their (overly) optimistic take on interdisciplinarity seemed to be rooted in the fact that they made sense of disciplines as focusing on different topics, rather than acknowledging that underlying values and assumptions vary wildly across disciplines. As such, they saw the advantages of interdisciplinary work—more diverse knowledge about the topic at hand—without being aware of its challenges—deeply rooted, persistent and fundamental differences of epistemological and ontological beliefs.

An example of a student in whom we observed naïve behaviour is S4, who has a humanities background. During in-class conversations, she contributed little of her own academic knowledge and asked few content-related questions of fellow students or teaching staff. She either remained quiet or contributed to the team discussions in a more process-oriented way, by taking notes, relaying knowledge or taking on organizational tasks such as planning or dividing tasks. In the following quote one of her fellow students (S19) shares an experience with S4 during the journal club exercise:

“Yeah, I think, I first offered my opinion of what I thought the paper was about and how it applied and [S4] kind of agreed and then we ended up writing our key points on the sticky notes, based on what I said. But I didn't really hear if [she] had any other distinct opinions on it. [She] just kind of agreed and said: ‘Yeah that's pretty much the main point and that's what I get from it’”—Student 19 (interdisciplinary programme) about Student 4 (humanities)

This description shows that S4 and S19 did not engage in interdisciplinary knowledge integration, as they settled for the explanation that S19 gave about the paper and S4’s view was not represented in their conversation. Consequently, the conversation remained superficial and does not generate new insights.

We observed a similar pattern during an exercise in which the students created a causal tree of the topic they were working on. A group of students discussed whether a certain concept is a cause or a consequence of plastics pollution. When they did not immediately agree with each other, they decided to place the concept in two different locations (both as cause and consequence) of the causal tree, rather than engaging in an in-depth discussion of what the concept means and why different people hold different opinions. As they avoided addressing this difference of opinion, they failed to realize the potential to learn about each other’s perspectives and to enrich their understanding of the topic. We saw that the students who exhibited naïve behaviour tended to avoid conflict rather than engage in constructive disagreement about differences of opinion that could result in learning about different perspectives and enriching understanding.

Two additional characteristics that we observed to be typical of naïve behaviour are low awareness of and attention to disciplinary differences, and limited insight into the values and assumptions behind their own academic knowledge. These combine to yield low interdisciplinary consciousness (Kjellberg et al. 2018), which is illustrated by the following example of S11. She described that it is important for her that her research focuses on concrete solutions and has practical implications. She mentioned that some of the students in her group seemed to focus more on describing phenomena or problems rather than working towards practical solutions. When asked about what could be the rationale for her fellow students’ view, she said the following:

“See, maybe they just want to deliver a good report for the course, just describing the problem. Maybe they don’t necessarily feel like they have to deliver something that others can continue with. They just describe the whole problem, and that’s it. In the course we also don’t have to write something that has practical relevance.”—Student 11 (exact sciences)

This quote demonstrates that S11 observed a difference between her and her fellow students in how they view the role of their research. Although teaching staff and other students identified this as a difference rooted in different disciplinary backgrounds, S11 seemed unaware of this. Even when asked about it repeatedly and explicitly, she kept making sense of the differences in terms of practical and social drivers, without connecting it to the values and assumptions related to their respective (disciplinary) backgrounds.

Taken together, collaboration that is characterized by naïve behaviour is seemingly smooth, because conflict is rare, collaborators are optimistic about interdisciplinarity and are consequently motivated to do interdisciplinary work. This motivation and optimism seem to be rooted in an incomplete understanding of what interdisciplinary collaboration entails which underestimates its challenges. As such, naïve collaborators are committed to delivering a product together and see value in cross-disciplinary collaboration (as they see it), but do not truly engage in the process of interdisciplinary collaboration to challenge their own and others’ perceptions and ideas. This behaviour is in accordance with the type of interdisciplinarity that Mansilla (2005) described and coined “naïve interdisciplinarity” which is characterized by the lack of integration of disciplinary perspectives and the lack of their representation in interdisciplinary work. Therefore, this seemingly smooth collaboration impedes knowledge integration, because the diversity of knowledge in the cross-disciplinary team is smoothed over rather than wielded to realize the potential of interdisciplinary teamwork to gain a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the topic (DeWulf et al. 2004). The absence of conflict we observed hampers knowledge integration, as conflicting views are considered to be the starting point for building common ground and subsequently constructing a more comprehensive understanding (Repko and Szostak 2020).

Assertive

Another typical pattern of behaviour that we observed in interactions among students, was assertive behaviour. This was the type of behaviour that we anticipated encountering in an interdisciplinary course. Assertive behaviour is characterised by strong disciplinary perspectives, rigidity of opinions and views, overrepresentation in interactions, and a superior attitude towards other disciplines.

An example of assertive behaviour became clear with S1 (health & life sciences) throughout the course. She had a very strong quantitative grounding, and she often brought up her wish to include quantitative measures during the course. Her contributions were perceived as enriching the teamwork by her fellow students. S15 put it as follows: “[S1] has a very clear direction in mind and [she] makes sure that that is where she is heading for, and that is interesting.” Yet, S1 also demonstrated behaviour that prevented knowledge integration. For instance, she was experienced as being judgmental about the contributions from other fields, and did not seem to truly value research from other fields as highly as from her own field. For instance, in the context of the journal club, S22 observed a heated discussion between S1 (health & life sciences) and S15 (social sciences) about their respective papers. In one of her written reflections, S22 wrote the following about this interaction:

“[S1] and [S15] didn’t agree with the methods used in each other’s paper, they didn’t think each other’s papers were good papers. I found that really interesting to see. I think that after the discussion they may have changed their views a little, but I don’t think that [S1] has really accepted that [S15]’s way is also a good way of conducting research”—Student 22

This quote illustrates that S1 was perceived as not open to S15’s view. The fact that she did not seem to accept S15’s approach as valid indicates that she did not value S15’s view and was unwilling or unable to critically reflect on (the limitations of) her own view. This prevented them from reaching shared understanding. We observed that as a consequence of their assertiveness and tendency to push their own rather than accept others’ knowledge contributions, assertive behaviour often resulted in overrepresentation in the process and consequently also in the product. This hampers integration of different knowledge bases. Because of their strong stance and resistance to changing their minds, students who show assertive behaviour may get into conflict, especially with others who behave similarly.

Moreover, acting assertively may—consciously or unconsciously—result in taking a superior stance towards team members from other fields. The following quote gives an example of a student who expressed a sense of greater importance and value of her own knowledge from her own field (exact sciences) compared to those of others (social sciences), indicating superiority:

“Yes, we can learn from each other, when we see the different disciplines and the value of the different disciplines. But for them that means that they see something that they don’t understand, so they’ll attach more value to it. They will maybe realize that if these technical aspects are something that they should take along, they will then depend on others who do possess this knowledge. While for me, it’s an insight that their disciplines can be supportive, but I can’t immediately think of anything that they contribute that I would never be able to come up with myself.”—Student 21 (exact sciences)

In this quote, S21 described that she perceived an asymmetrical interdependence between social and exact sciences, by which she implied superiority of her own field (exact sciences) over other fields (social sciences). She seemed to be at least partly unaware of her superior stance, as there is a discrepancy between what she said at first (“we can learn from each other”) and what she showed immediately after (“I can’t immediately think of anything that they contribute that I would never be able to come up with myself”). In line with the general (perceived) hierarchy of knowledge and disciplines and the literature (Harris et al. 2009), we observed superior and assertive behaviours most commonly among students with backgrounds in the exact and life sciences, and less commonly in students trained in social sciences and humanities.

Taken together, collaborators who demonstrate assertive behaviour are of value to a cross-disciplinary team as they bring unique knowledge and perspectives to the collaboration. As such, their contributions enrich teamwork. This was expressed by students and is also echoed in literature as it has been reported that the contribution of more unique knowledge leads to better and more comprehensive results (Godemann 2008). However, assertive behaviour hampers knowledge integration through the tendency of people who exhibit it to inflexibly hold on to their own views and through overrepresentation of assertive voices that leave little room for the representation of others’ views.

Accommodating

We observed interactions in which students demonstrated accommodating behaviour. Accommodating behaviour was characterized by listening and asking questions, relying mostly on others’ knowledge and ideas, underrepresentation of accommodating voices in the process and underrepresentation of their knowledge in products, and possible feelings of inferiority. For example, we observed typical accommodating behaviour in S22 (interdisciplinary program) throughout the course. In class, she often asked questions and tended to listen well. Moreover, she expressed that she did not hold a strong disciplinary identity, because she was trained broadly. In the following quote she describes her role in a discussion with classmates:

“Then we formed a problem map. I took an active role in this discussion. I tried to ask people what they thought, and why. If something was not clear or could be interpreted ambiguously, I asked them to explain further. I tried to not impose my opinion in the discussion, even though I was the one holding the chalk and writing most things on the board. I tried to give everyone a voice in the discussion.”—Student 22 (interdisciplinary program)

This example shows that S22 took on a neutral role in the process, asking questions and observing, rather than mingling in on the content of the discussion. She explained in a reflection interview that this behaviour comes naturally to her: she is interested and enjoys learning about others’ views: “I just like asking why, why, why, why”.

Several students who displayed accommodating behaviour expressed that they experienced a feeling of disciplinary inferiority, as they assumed or feared that their classmates did not value their fields’ knowledge. In the following quote, S5 (humanities) provides insight into her feeling of disciplinary inferiority:

“I found it very interesting to collaborate with a math student. But the other way around I’m not always sure if people also see it that way… That’s why I found it quite hard to bring [the contribution from my field] that first time. […] I feel like it’s looked down upon. Probably that is not even the case. But that feeling is fueled by the fact that from an early age onwards you’re told that hard science is the real science, and [my field] is more like, feminine, the feminine humanities versus the hard sciences”—Student 5 (humanities)

In line with the general (perceived) hierarchy of knowledge and disciplines as also reported by Harris et al. (2009), we observed these feelings, expressions, and behaviours of inferiority more commonly among students trained in social sciences and humanities, and less among science students. Moreover, accommodating behaviour was more common among students trained in broad, interdisciplinary programmes compared to students trained in more specialized fields, in line with literature that reports interdisciplinarily trained people may feel like they lack expertise in any particular field (Darbellay 2015).

Overall, accommodating behaviour contributes to interdisciplinary integration by facilitating the process of knowledge exchange by listening well and asking questions. As such, collaborators who behave accommodatingly hold the potential to play an important role in bridging disciplinary divides within cross-disciplinary teams, as is also described by Maglaughlin and Sonnewald (2005) and echoed in the view that interdisciplinary teamwork can benefit from one or more team members who function as ‘connectors’ who are specialized in integration and implementation to harness the knowledge contributions of other (disciplinary) team members (Bammer et al. 2020; Pennington et al. 2020). However, they often do not contribute much of their own knowledge to the content of the project, and instead take the role of process facilitator. Taking a predominantly procedural role prevents collaborators who exhibit accommodating behaviour from contributing the knowledge that they hold and thus limits the diversity of knowledge available to the interdisciplinary effort. Consequently, when collaborators exhibit accommodating behaviour, they depend on teammates who contribute their own knowledge to make their contribution to interdisciplinary knowledge integration. Moreover, when not contributing their knowledge and perspectives, they deprive the team of yet another take on the topic that could potentially enrich their joint understanding.

Integrative

The fourth, and last, pattern of behaviour that we observed in our course is what we call integrative behaviour. Integrative behaviour was characterized by actively connecting one’s own and others’ knowledge. Students who demonstrated integrative behaviour were relatively uncommon.

In the following quote, S7 (interdisciplinary programme) described an interaction between herself and S17 (management studies), in which she connected terminology that S17 used to key concepts in her own field to create shared understanding:

“So I try to translate what [S17] says into my ‘language’ [...] For instance, [she] started talking about improving life. Then I recognized that that also holds a connection to value, at least what I mean when I use the concept value. Then I explained that to [her], and also explained about ‘the bottom of the pyramid’, that there are a lot of people in the bottom classes and that that is also exactly where that value proposition lies.”

When further probed about how this translation came about, she explained the following:

“By giving a definition of a word and asking what they mean with a word. I think I literally asked her: ‘can you define what you mean by the meaning of life?’. Then I check with myself whether I understand […] and if I don’t understand, then I ask again. Or I say that I don’t understand, and ask whether she can explain it again in other words. So, there is a kind of checking loop: do I understand? No, then ask follow-up questions. And as soon as we reach an explanation that I do understand, I confirm. Then we agree on a definition that we both understand and can work with. That’s then that definition of that word, you have kind of a convention. […] This doesn’t have to be entirely new, but it does consist of both worlds, both people. Both parties contribute something. Together you build your own language that we use in that discussion. [...] So, by listening and truly trying to understand what they mean to say. And then try to relate to it, and also realize they are coming from another academic environment than your own.”—Student 7 (interdisciplinary programme)

This quote is an illustration of S7’s ability to create a shared understanding that combines her own and S17’s knowledge bases. Rather than steering away from things that she did not understand, S7 takes a moment of unclarity as the starting point for further exploration to expand their shared understanding. She brought her own knowledge to the interaction, by sharing key concepts (value, value proposition, ‘bottom of the pyramid’) from her field and explaining those to S17. And she engaged with the knowledge that S17 brought to the conversation (e.g., ‘meaning of life’) by trying to understand, summarizing in her own words, checking whether she understood correctly, and asking questions. This was a process of multiple rounds of recursion resulting in a conversation of a dialogical nature (Tsoukas 2009). This interactive process of contributing her own knowledge and engaging with S17’s knowledge allowed her to actively seek connections and together with S17 create shared understanding that integrated knowledge from both of them, applied to the context of the project, and represented ideas that are new (to them). In doing so, she aimed for what she referred to as a ‘convention’, i.e., an agreement in the context of the joint project that does not necessarily represent the viewpoint of either of them outside the context of the joint project. Therefore, this is as Defila and Di Giulio (2017) describe a consensus, not in an ‘agreement in an everyday sense’, but rather an agreed upon description that makes sense for the context of the joint work that aligns with the views, beliefs, assumptions of the collaborators’ backgrounds. The joint ‘language’ that S7 describes is similar to what Galison (1997) calls pidgin or creole, a language that neither of the collaborators is native in, but that they both understand for the purpose of their interaction. Striving for this consensus, S7 does not attempt to convince S17, but rather embraces the possibility of each holding their own views while collaborating on the basis of an agreed upon consensus. As such, she exhibits a plural understanding in which multiple ways of understanding the topic of understanding can exist alongside each other, rather than one of them having to be right, leaving the other to be wrong.

Epistemic competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration

The findings presented so far imply that interdisciplinary knowledge integration requires contributing one’s own knowledge and engaging with each other’s knowledge, because we saw that the absence of either or both of these behaviours—in naïve, assertive, and accommodating behaviour—hampered knowledge integration in teams. To make this point explicit, consider teams of collaborators who all exhibit the same type of behaviour. With only naïve behaviour, differences are glossed rather than harnessed to avoid conflict. With only assertive behaviour, knowledge integration will be hampered because collaborators will hold on to their own views and not manage to make links and arrive at an integrated, more comprehensive understanding. And teams of only accommodating behaviour will lack content and disciplinary perspectives that can be integrated, because accommodating behaviour relies on others to contribute knowledge in the absence of which there is no knowledge for the accommodating team to engage with. When collaborators contribute their own knowledge and engage with each other’s knowledge—as is the case in integrative behaviour and in interactions between assertive and accommodating collaborators—we saw team interactions that aided knowledge integration, such as repeated questioning to create understanding and linking of concepts from the knowledge bases of different collaborators.

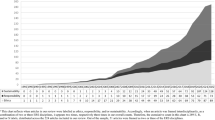

As interdisciplinary knowledge integration requires these two sets of behaviours—contributing one’s own knowledge and engaging with others’ knowledge—and competencies are defined as the ability to demonstrate certain behaviour (Heinsman et al. 2007), it follows that interdisciplinary knowledge integration also requires two corresponding sets of competencies: Epistemic Stability (ES) competencies, and Epistemic Adaptability (EA) competencies. ES comprises competencies that allow a collaborator to contribute their own knowledge to the interaction, whereas EA includes competencies that enable engaging with others’ knowledge. We call these epistemic competencies, because they describe how students deal with knowledge—both their own and the knowledge of others—to achieve interdisciplinary knowledge integration. When individuals exhibit behaviour that is indicative of both ES and EA, we consider this a demonstration of Integrative Competence. Figure 1 provides an overview of the behavioural patterns that we observed, and their relationship to the two sets of epistemic competencies (ES on the y-axis and EA on the x-axis).

We continue this section by describing the competencies that fall within these two sets, based on insights from empirical research and a review of the literature. A third set of competencies only arise through the presence of ES and EA competencies, we call these integrative competencies.

Epistemic Stability—In the examples of assertive and integrative behaviour, we saw that students contributed their knowledge by sharing concepts, theories or methods. As such, they demonstrate that they have sufficient understanding of concepts in their fields (Nash et al. 2003; Mansilla et al. 2005; Haider et al. 2018; Nurius and Kemp 2019) to apply this knowledge to diverse contexts and explain it to others unfamiliar with their field; this indicates performance-based understanding (Mansilla 2005). Their behaviour is also indicative of communicative skill to explain knowledge from their field (Nurius and Kemp 2019). Moreover, they show that they have confidence (Nash et al. 2003; Nurius and Kemp 2019) about their understanding of their own field and their field’s relevance to the project. This allows them to bring their knowledge to the interaction and stand by it, even if others do not (immediately) understand it or do not agree with it. In addition, the examples also show their drive to contribute knowledge from her field (Falcone et al. 2019), as they opt to bring unique knowledge to the interaction, whereas sticking to common knowledge would have been considerably easier and quicker. This is closely related to their academic identities (Di Giulio and Defila 2017) and motivation to act as a representative of their field in the cross-disciplinary team. In contrast, in accommodating and naive behaviour at least some of these competencies are absent. The fact that those students recurrently refrain from contributing their knowledge to the teamwork throughout the course may be due to limited knowledge in their own field, insecurity about their proficiency in their field or its relevance to the joint effort, a weak identity or drive to represent their field, or a lack of awareness about disciplinary differences and one’s own unique knowledge. For instance, we saw that S22 explicitly expressed that she did not hold a strong disciplinary identity, and that S5 expressed an insecurity to contribute insights from her field because she feared the perceived inferiority of her field.

Epistemic Adaptability—Basic understanding of others’ fields helped collaborators understand each other’s contributions and improved their ability to engage with those contributions. For instance, S22 was trained broadly, and that helped her understand and relate to the views of different students and take on a bridging role in their conversation. Moreover, in the examples of accommodating and integrative behaviour, we saw that students engaged with the knowledge of others by trying to understand, asking questions, and accepting and reproducing the other’s views and knowledge for the joint project. By trying to understand, engaging in deep listening and asking questions, these students demonstrated intellectual curiosity (Nash et al. 2003; Strober 2006; Nurius and Kemp 2019). For instance, S22 kept asking why and expressed that she was—and generally tends to be—curious to know more and understand better. By taking others’ input seriously and not (directly) disregarding ideas different from their own, these students also demonstrate suspension of judgement that allows them to be open to other ideas and value different perspectives (Nash et al. 2003; Strober 2006; Thompson 2009; Parker 2010; Larson et al. 2011; Nurius and Kemp 2019). Moreover, we observed that these students expressed when they did not understand something, and sometimes changed or expanded their view based on new insights provided by others. This illustrates an attitude of epistemic humility (Nash et al. 2003; Gardiner 2020), acknowledging the limitations of one’s own knowledge. On the contrary, assertive and naive behaviour illustrates the absence of at least some of these competencies. The fact that they do not engage actively with others' knowledge may be caused by a lack of intellectual curiosity to understand the others’ reasoning, strong prejudices and thus not being open to other views, or conviction that one’s own field holds all the answers (i.e., the absence of epistemic humility). We saw, for instance, that S1 had a rigid image of good science as being quantitative and lacked an open attitude to critically question her view. And S21 expressed a seemingly implicit assumption or prejudice of superiority of sciences compared to social sciences, indicating a lack of humility.

Integrative Competencies—In addition to the competencies that relate specifically to the ES or the EA dimensions, we also observed competencies that students only demonstrated possessing if they mastered ES and EA competencies. These integrative competencies are pluralistic understanding and functional disagreement. In the example of S7 and S17 we observed that they reached what S7 calls a “convention”, or as Defila and Di Giulio (2017) call it: consensus. S7’s ability and willingness to agree on such a consensus, is indicative of a pluralistic understanding of the topic at hand, allowing for multiple equally valid interpretations and acceptance of their coexistence (Lélé and Norgaard 2005; Miller et al. 2013). Moreover, we observed in integrative behaviour the willingness to address conflicts or disagreements, rather than ignoring them or smoothing them over. In the example of S7, she actively searched for the points of unclarity or disagreement by repeatedly asking questions, which demonstrates that she saw disagreement and misunderstanding as a learning opportunity rather than an obstacle (Freeth and Canglia 2020; Monteiro and Keating 2009).

Table 1 gives an overview of the ES, EA and integrative competencies building onto the competencies identified in previous studies.

Discussion

This study offers a framework founded in empirical research and a review of the literature for understanding interdisciplinary competencies that are essential to addressing contemporary sustainability issues. We advance the field beyond merely listing competencies by shedding light on how interplaying competencies shape the individual ability to engage in knowledge integration, which is the defining characteristic of interdisciplinarity (Klein 2010). To understand competencies for interdisciplinary knowledge integration, we introduced the concepts of Epistemic Stability (ES)—the competencies to contribute one’s own academic knowledge—and Epistemic Adaptability (EA)—the competencies to engage with others’ knowledge. This study shows how an individual’s ability to engage in knowledge integration is shaped by ES and EA competencies.

The distinction between ES and EA echoes the paradox of interdisciplinarity that depends on, but is also challenged by, knowledge diversity (Crowley and O’Rourke 2020) and aligns with literature describing the process of knowledge integration as depending on the exchange of unique knowledge as well as the creation of cohesive conceptual understanding by the whole team (Godemann 2008). Moreover, the distinction between ES and EA aligns with, and adds to, the conceptualization of T-shaped researchers, who are individuals with deep specialized expertise in a particular (disciplinary) field (vertical leg of the T) and broader expertise in neighbouring disciplines and general skills to collaboration and communicate across disciplines (horizontal head of the T) (McIntosh and Taylor 2013). And similarly, it aligns with the conceptualization of interdisciplinary competencies as shield-shaped that builds onto the notion of T-shape, further emphasizing the importance of holding or acquiring understanding of the fields of one’s collaborators (Bosque-Pérez et al. 2016). A similar link can be made between the conceptualization that we propose in this study and the conceptualization of Haider et al. (2018) who argue that rigorous interdisciplinary sustainability science requires epistemic agility and methodological grounding. These conceptualizations, however, define the necessary assets more narrowly, as the T-shape (McIntosh and Taylor 2013) as well as the methodological grounding (Haider et al. 2018) focus exclusively on knowledge and skills, whereas we aimed to gain a holistic understanding of epistemic competencies that contribute to the ability to demonstrate integrative behaviour, including mindsets and attitudes.

The four behaviours we described demonstrate that collaborators can hold different combinations of ES and EA competencies. The naïve behaviour that we observed in our study, shows similar characteristics to what Mansilla et al. (2009) call naïve interdisciplinarity and Haider et al. (2018) refer to as the “conceptual la-la-land”. When assessing interdisciplinary student work, Mansilla et al. (2009) considered this work to be naïve when disciplinary perspectives are missing and can thus not be integrated, so the end result is limited to a common-sense understanding. The assertive behaviour we report aligns with the frequently described tendency of experts to hold their own discipline and disciplinary knowledge in higher regard than others’ and talk about their own perspective rather than listening to others (Brown et al. 2015; Richter and Paretti 2009; Strober 2006). Both in our study and in the literature, this behaviour is most prominent among highly specialized collaborators; in the case of our course these are students who are trained in highly specific fields, and in literature this becomes apparent among experienced researchers who have been active in a field for a long period of time (Brown et al. 2015; Richter and Paretti 2009; Strober 2006). In contrast, accommodating behaviour is far less described in the literature. It does, however, resonate with the findings of Kjellberg et al. (2018) that students can also develop discipline-crossing competencies before they are strongly grounded in one discipline.

As such, our conceptualization of competency dimensions and behaviours combines insights from previous reports that depart from a dominant disciplinary perspective (Brown et al. 2015; Strober 2006), and reports on the “undisciplined journey” (Haider et al. 2018; Kjellberg et al. 2018). The two-dimensional interdisciplinary competency space reconciles these isolated reports and captures the different possible assets collaborators can bring to interdisciplinary teamwork. This framework holds the promise of informing the design of interventions to support the development of competencies for interdisciplinarity in educational but also research contexts.

Implications

Our study shows that the majority of master’s students in our course did not possess integrative competence and even a substantial number of students exhibited naïve behaviour. This is not surprising, as students are still in the process of learning and acquiring competencies, and their prior experience with interdisciplinary work varied widely. The fact that the students in our course proved to be lower on ES competencies than previously reported for later career researchers (Brown et al. 2015; Strober, 2006) makes sense as they are early career scholars who are still acquiring expertise in one field and developing a professional identity. This, however, also raises the question of how to strike a balance in university courses, equipping students to address complex, inherently interdisciplinary sustainability issues without compromising ES to the extent that we end up with programmes that run an inch deep and a mile wide (Mansilla, 2005). This is also echoed in the finding by Kishita et al. (2018) that university programmes for sustainability either take a specialist or a generalist approach, dealing with the often experienced and reported trade-off between depth and breadth in training for addressing sustainability issues. Moreover, Roy et al. (2020) report that interdisciplinary sustainability courses require a combination of training content and interdisciplinary competencies, and Pennington et al. (2020) report that educators struggle with training students in discipline-specific and discipline-spanning competencies for sustainability issues. Moreover, on the individual level, this tension between depth and breadth poses the challenge of creating and adopting an academic identity and team role that allows one to share knowledge on the topics of one’s expertise while also being an interdisciplinarian (Darbellay 2015). It should be noted that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this issue, or a universally ideal ratio of (disciplinary) specialization versus interdisciplinary integration. Rather, this balancing act depends on the ambitions of training programmes (Guimarães et al. 2019). This calls for careful consideration in course and program design to train ES as well as EA competencies, and balance breadth and depth in such a way that they fit educational goals and job market and societal demands, as well as prior experiences and backgrounds of learners.

Besides, this general recommendation for educators and education designers to carefully balance learning activities for the development of ES and EA competencies, the insights from our study, together with earlier lessons from literature, also provide more concrete handles for the design of interdisciplinary education for sustainability. Our findings that ES competencies are essential to interdisciplinary work, and that many Master’s students did not seem to be very epistemically stable, underlines that when turning to interdisciplinary training, training in specialized skills and knowledge should not be neglected altogether. Approaches such as the one described by Bosque-Pérez et al. (2016) could be helpful here. They describe an interdisciplinary program for PhD students who conduct individual PhD research in a specialized field while working in parallel in a cross-disciplinary team. Moreover, our findings stress the need to explicitly train students in competencies for interdisciplinarity, which requires not only acquiring knowledge about interdisciplinarity, but also gaining experience in interdisciplinarity to acquire skills (Bridle et al. 2013; Pennington et al. 2021), and reflection to develop an attitude that supports interdisciplinary teamwork (Parker 2010). To raise awareness of disciplinary differences that was quite commonly lacking in our cohort, as became clear from the students with naïve behaviour, one could use approaches such as the Toolbox dialogue method (Hubbs et al. 2020), as applied by Kjellberg et al. (2018) to support the development of interdisciplinary consciousness and by Pennington et al. (2021) to expose differences in epistemological assumptions to aid interdisciplinary teamwork.

A question that remains unanswered in this study is how individual competencies shape the performance of interdisciplinary knowledge integration at the team level. It does not seem necessary for all team members to possess full integrative competence to successfully integrate knowledge as a team (Bammer 2013). The model of pi-shaped collaboration that is described in literature, for instance, explicitly relies on collaboration between individuals with different specialized expertise (likely exhibiting assertive behaviour) and individuals with broad collaborative skills that help make the link between those specialists (accommodating behaviour) (Ceri 2018; Pennington et al. 2020). In this approach, individuals with high EA but low ES competence could be valuable to interdisciplinary efforts to build bridges between the knowledge bases of others who are with low EA but high ES competence, similar to what Maglaughlin et al. (2005) describe as “bridging”. And the other way around, individuals with high ES but low EA competence can be of value to the team by contributing their knowledge that others manage to link together.

Although a team may thus manage to integrate knowledge and deliver an integrated end result through different individuals displaying assertive and accommodating behaviour, we do expect that uniting these two competency sets in one individual—and thus exhibiting integrative competence—brings added value to interdisciplinary teamwork. In collaboration, knowledge integration requires transferring knowledge from one person to another (Haythornthwaite 2006; Xue et al. 2020). Thus, if a team displays only assertive and accommodating behaviours, but not integrative, then accommodating individuals would be responsible for facilitating the combination of knowledge shared by assertive individuals. This causes the knowledge transfer to require additional steps of transformation (Liyanage et al. 2009), because the knowledge shared by different assertive individuals has to be assimilated by the intermediary accommodating team members. This in turn may result in not all knowledge that is contributed by the assertive team members being integrated, when it is not fully understood by the accommodating team members. Furthermore, accommodating individuals can only integrate knowledge that is explicitly shared by assertive members, whereas tacit knowledge and unspoken knowledge remain unused. As such, unique knowledge held by team members is lost when knowledge integration depends on accommodating team members who interpret and integrate the contributions from teammates, rather than teammates connecting the contributions of others to their own knowledge bases directly as would be the case with integrative behaviour. So, the absence of individuals displaying integrative behaviour may limit the knowledge that is represented in the joint effort, creating extra translation steps that may cause knowledge, nuances, and details to be lost in translation and making teams more vulnerable to changes in composition. Therefore, we argue that integrative competence is likely to make collaborators as well as teams more versatile and agile. However, this hypothesis requires further investigation to fully fathom how the interaction of individual behaviours shapes team knowledge integration capacity and gain better understanding of the function of integrative behaviour and competencies in interdisciplinary knowledge integration.

Moreover, it has been reported that interdisciplinary team functioning emerges from a complex interplay between individual traits and competencies, and social team level processes (Lotrecchiano et al. 2016; Pennington 2016). How ES and EA competency sets in a continuous process of social learning shape interdisciplinary collaboration at the team level should be the subject of future research. This will require also considering social processes and social learning, disciplinary compatibility, and personalities, since these have previously been shown to affect team integrative capacity (Bromme 2000; Cairns et al. 2020; Krishnakumar et al. 2020; O’Rourke et al. 2019; Salas et al. 2018; Salazar et al. 2012). If the mechanisms through which individual competencies and other factors shape team integrative performance were better understood, additional interventions could be designed to actively facilitate cross-disciplinary teams in research and education to improve their integrative capacity. Furthermore, insight into the competence of teams and team members based on the proposed framework may inform interventions that specifically target competencies the lack of which hampers knowledge integration in particular research or education settings.

Finally, it should be added that sustainability issues not only require integration of knowledge across disciplines, but also between academic and practice knowledge (Clark et al. 2016; Robinson 2008). The framework we propose in this study was only based on empirical research in the context of cross-disciplinary teams, but future research may shed light on its relevance for collaboration between academics and team members from outside the academy (i.e., transdisciplinary collaboration).

Methodological considerations

Addressing complex sustainability issues requires integration of knowledge from different disciplines. Our representation of competencies in terms of ES and EA adds to the understanding of what knowledge integration actually entails and why it is difficult to achieve. There are, however, also limitations to the approach that we took in this study. These include the simplified representation of reality when developing a framework, the ambiguous definition of disciplines, the indirect observation of competencies in practice, and the relatively small number of students among the data for this study were collected.

First of all, a framework like the one we have presented is inevitably a simplified representation of reality. For the sake of clarity, competencies were considered in isolation, when they are in fact in a continuous and complex interplay with personality traits, experiences, social dynamics and contextual factors (Bromme 2000). As a consequence of the simplification, the behaviours we described may seem relatively rigid, stable, and ‘black and white’. These seemingly well-demarcated categories proved helpful in understanding the framework and data, even though they may not do justice to all nuances in practice such as possible development throughout the course and differences in behaviour depending on contextual factors. We consider it acceptable to consider students’ competencies as more or less stable throughout the course, given that an 8-week course is basically only a snapshot of the students’ competencies at a single moment in a single context. People are likely to behave differently in different contexts and different moments in time. On top of that, students are likely to still be in the process of developing these competencies and may thus be expected to change if they were followed over a longer period of time, especially while being involved in cross-disciplinary teamwork and training these skills explicitly.

Second, another complicating factor in dealing with this student cohort, over and above the interpretation of the results, is the high diversity of students and study backgrounds. Disciplines are by definition diverse in their level of specialization, breadth and uniqueness of methods and perspectives and are not as stable as the presentation of distinct categories may imply (Klein 1983). In addition, the master’s programmes represented in the cohort do not translate directly into monodisciplinary fields, as several are offered across departments or even faculties. And then, there is a wide diversity of prior educational, professional and personal experiences that students bring to the course that also shape their scientific identities and views. In other words, there is no straightforward translation between study programme and disciplinary perspectives, and the majority (if not all) of the students cannot be considered to represent a single monodisciplinary perspective.

Third, our conclusions about competencies were the result of the indirect insights that behaviour provides into the mastery of competencies. The combination of observations and student reflections helped us triangulate and allowed us to also detect the absence of behaviour through observation and student cross-reporting. However, both methods also have limitations. The observations allowed us to distinguish between what students say and what they display, and thus eliminate socially desirable answers, but did not provide direct insight into competencies. The reflections by the students, on the other hand, provide more direct insight into students’ competencies, but are subject to their own interpretation. This means that student reflections may be shaped by what they think is expected or desired of them, and their own (possibly limited) understanding of their own behaviour and underlying processes.

And lastly, the framework we present in this study came about through the combination of a thorough study of literature and empirical research. As such, our empirical insights are embedded in and build upon existing insights and connect findings to practice, increasing the likelihood that they directly inform educational and research approaches and answer the call by Salas et al. (2018) to connect theory and practice for interdisciplinarity. Our empirical study was based on data from a modest cohort of 19 students. Because of the connection to literature, the repeated observation of the behaviours in different students, and the diversity of student demographics and backgrounds, we feel confident that the findings are sufficiently supported by our data in spite of the relatively small cohort. It cannot be ruled out, however, that more nuances and influencing factors could be identified when studying a larger cohort, as this would allow for greater sensitivity to detect outliers and general patterns.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the framework we propose in this article contributes to understanding interdisciplinary knowledge integration to address complex sustainability issues. It demonstrates that interdisciplinary teamwork requires navigating a paradox inherent in interdisciplinarity and also requires two sets of epistemic competencies: epistemic stability and epistemic adaptability. By furthering the understanding of interdisciplinary competencies for sustainability, the proposed conceptualization holds the promise of informing interventions and training for students, researchers and practitioners in the field of sustainability. The framework offers handles for assessment, targeted interventions based on individual and team needs, and training that fits the competency levels and combinations that are shaped—among others—by career phase and training. Moreover, our study invites future research to understand interdisciplinary knowledge integration at a team level, translate the competency framework into concrete training and intervention strategies, and study the relevance of the framework to other contexts such as knowledge integration between academics and nonacademics.

References

Ashby I, Exter M (2019) Designing for interdisciplinarity in higher education: considerations for instructional designers. TechTrends 63(2):202–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0352-z

Bammer G (2013) Disciplining interdisciplinarity: Integration and implementation sciences for researching complex real-world problems. ANU Press, Canberra

Bammer G, O’Rourke M, O’Connell D et al (2020) Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0380-0

Barth M, Godemann J, Rieckmann M, Stoltenberg U (2007) Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int J Sustain Higher Educ 8(4):416–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370710823582

Bosque-Pérez NA, Klos PZ, Force JE, Waits LP, Cleary K, Rhoades P et al (2016) A pedagogical model for team-based, problem-focused interdisciplinary doctoral education. Bioscience 66(6):477–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw042

Bridle H, Vrieling A, Cardillo M, Araya Y, Hinojosa L (2013) Preparing for an interdisciplinary future: a perspective from early-career researchers. Futures 53:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2013.09.003

Bromme R (2000) Beyond one’s own perspective: the psychology of cognitive interdisciplinarity. Practicing interdisciplinarity. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, pp 115–133

Brown RR, Deletic A, Wong TH (2015) Interdisciplinarity: how to catalyse collaboration. Nature News 525:315–317. https://doi.org/10.1038/525315a

Brundiers K, Barth M, Cebrián G, Cohen M, Diaz L, Doucette-Remington S et al (2021) Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain Sci 16(1):13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00838-2

Cairns R, Hielscher S, Light A (2020) Collaboration, creativity, conflict and chaos: doing interdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustain Sci 15(6):1711–1721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00784-z

Ceri S (2018) On the role of statistics in the era of big data: a computer science perspective. Statist Probab Lett 136:68–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spl.2018.02.019

Clark WC, Van Kerkhoff L, Lebel L, Gallopin GC (2016) Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(17):4570–4578. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601266113

Cronin MA, Weingart LR (2007) Representational gaps, information processing, and conflict in functionally diverse teams. Acad Manag Rev 32(3):761–773. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275511

Crowley S, O’Rourke M (2020) Communication failure and cross-disciplinary research. The toolbox dialogue initiative. CRC Press, Florida, pp 1–16

Darbellay F (2015) Rethinking inter-and transdisciplinarity: undisciplined knowledge and the emergence of a new thought style. Futures 65:163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2014.10.009

Defila R, di Giulio A (2017) Managing consensus in inter-and transdisciplinary teams: tasks and expertise. The Oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 332–337

Dewulf A, Craps M, Dercon G (2004) How issues get framed and reframed when different communities meet: a multi-level analysis of a collaborative soil conservation initiative in the Ecuadorian Andes. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 14(3):177–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.772

Di Giulio A, Defila R (2017) Enabling university educators to equip students with inter-and transdisciplinary competencies. Int J Sustain High Educ. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2016-0030

Donaldson A, Ward N, Bradley S (2010) Mess among disciplines: interdisciplinarity in environmental research. Environ Plan A 42(7):1521–1536. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42483

Drach-Zahavy A, Somech A (2001) Understanding team innovation: the role of team processes and structures. Group Dyn Theory Res Pract 5(2):111–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.5.2.111