Abstract

Sustainability research is characterized by a plurality of interests, actors, and research traditions. Sustainability is a widely used concept across multiple disciplines and often a cross-cutting theme in different research projects. However, there is a limited understanding of how researchers from multiple disciplinary backgrounds approach sustainability and position themselves in sustainability research as a part of their researcher identity. Previous studies among sustainability science experts have indicated diverse approaches and definitions of the socio-political, epistemic and normative dimensions of sustainability. In this study, we use semi-structured interviews with researchers (N = 7) and a survey distributed to two academic institutes in Finland (N = 376) to examine how researchers relate to sustainability research through the notions of identity as ‘being’ and ‘doing’ and how the differing ways to relate to sustainability research shape preferred definitions and approaches. The examination of perspectives among researchers enables the identification of diverse views related to sustainability and, consequently, sheds light on what kinds of ideas of sustainability get presented in the research. We conclude that understanding different identities is crucial for negotiating and implementing sustainability and developing sustainability research, requiring more attention to researchers’ positionality and reflexivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the past 30 years, sustainability has evolved into a widely used buzzword and boundary concept bridging science, policy and society (Kajikawa et al. 2014; Kates 2011; Lundgren 2021; Scoones 2007). For example, in the Web of Science there are more than 38,000 articles that use the term ‘sustainability’ in the year 2020 (Web of Science 2021). Between 2014 and 2020, over 220,000 articles use the concept of sustainability mostly in the framework of sustainable development, with a remarkable increase that has taken place after the introduction of the UN Global Action program Agenda2030 (Web of Science). As Agenda2030 reveals, sustainable development and related research cover all spheres of life, although the environmental aspect, or environmental sustainability, is the most prominent field in the research (Kajikawa et al. 2014).

Given the huge amount and wide scope of sustainability research (Lundgren 2021), but also the broadness and vagueness of the concept (Dryzek 2013), there are multiple ways to understand and frame the concept of sustainability or sustainable development (Miller 2015; Purvis et al. 2019). For example, Salas-Zapata and Ortiz-Muñoz (2019) distinguish four types of sustainability expressions among scholars: sustainability as (i) a set of guiding criteria for human action; (ii) a goal of humankind; (iii) an object of research; (iv) and/or an approach of study. As a result, the scope of sustainability research is ranging from research related loosely to covering some of the aspects of sustainability to sustainability science as a research field centered around sustainability questions. Sustainability science started to develop in the early 2000s to assess and explore the fundamental character of interactions between nature and society and enhance society’s capacity to guide those interactions along more sustainable trajectories (Kates et al. 2001, p. 641). Since then, sustainability science has become an established research field. Although its scope is still broad and evolving, it can be characterized as a problem-based, integrative, interactive, emergent and reflexive research field that involves strong forms of collaboration and partnerships (Haider et al. 2018), which makes it different from overall sustainability research. Given this wide scope of sustainability research with more specific and ambitious research frames to more general ones, there is a huge variety of research topics, approaches and methodologies (Haider et al. 2018). However, despite the broadness of the research field, researchers are seldom explicit about how they define the concept of sustainability or how they approach it (ibid.). Sustainability-related research hence is versatile in its depth of engagement with sustainability issues, as well as approaches and strategies to study and enact sustainability.

Besides having a wide scope in approaches and conceptualizations, sustainability research is also normative (Miller 2015), bringing together different epistemic views (related to the validation of knowledge and justified beliefs) that are associated with non-epistemic views (e.g., personal values). The epistemic and non-epistemic views determine the ways scientists interpret the normative dimensions of sustainability research, influence the design of the research agendas and shape the perceived credibility of alternative normative claims and concerns (Miller 2013; Nagatsu et al. 2020). Normativity is an integral part of sustainability research, and therefore understanding and dealing with normativity is a key competence of a sustainability researcher (Wiek et al. 2011). Furthermore, researchers may adopt various roles in sustainability research, from the observer, facilitator to change agent, depending on the research setting and their personal skills and interests (Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014), employing/accomplishing different normative views on if and how changes should be enacted in the world. Overall, normativity and different roles in sustainability research call for greater reflexivity among the participants in research projects, including researchers’ own values and aims (Horcea-Milcu et al. 2018; Nagatsu et al. 2020), that are also ingredients of researchers’ personal and professional identity.

The interlinked aspects of many conceptualizations as well as the normative views and goals that form a plural research landscape in sustainability research need to be constantly reflected and navigated. The plurality has vastly been brought into focus in terms of diverse epistemic starting points in inter- and transdisciplinary sustainability research. Recent research has for example shed light on different interpretations of sustainability researchers’ views and research agendas/approaches regarding sustainability (Miller 2015; Wuelser 2014) and different ways of being and doing sustainability research (see e.g., Hilger et al. 2018; Horlings et al. 2020; Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014). However, there is less understanding of how researchers inside and outside sustainability-related research conceptualize sustainability and how these conceptualizations are related to researcher identities. The calls for greater reflexivity among sustainability researchers (e.g., Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014; Horlings et al. 2020) have overlooked the contribution of professional identity to shaping positionality in sustainability research. The diverse definitions and approaches and plural epistemic views on sustainability can be seen as related to the formulation of researcher identities. These perspectives on sustainability can be used as a tool to understand the similarities and differences of researchers’ professional development, social categorization and group affiliation over time (Hammack 2015). Moreover, as problem-solving is at the core of sustainability research and sustainability research aims at having a real-world impact, it is crucial to shed light on the deeper levels of how sustainability research is related to and formed through researcher identities.

In this article, we explore the ways in which researcher identities and conceptualizations of sustainability are related. We aim to answer the following research questions: (i) How do researchers relate to sustainability research through ‘being’ sustainability researchers and ‘doing’ sustainability research? (ii) How are the different definitions of sustainability and research approaches associated with ‘being’ and ‘doing’? These questions aim at starting the discussion on the role of the researcher identity in sustainability research which is an area that is profoundly plural and normative as noted above. The richness of conceptualizations and interpretations of sustainability can be seen as a strength regarding sustainability transitions and transformations but has also been considered as one of the challenges in sustainability research, hindering communication and collaboration between researchers (Adger 2006; Cutter et al. 2008; Gallopín, 2006; Shahadu 2016). Understanding this richness is crucial for the collaboration of researchers with different disciplinary backgrounds (Hakkarainen et al. 2021). Normativity and positionality, in turn, may raise doubts about the quality and validity of the research, if reflexivity is not sufficiently practiced. Additionally, several universities and research institutions are establishing sustainability centers and institutes (Salovaara et al. 2020; Slager et al. 2020; Spoelstra 2013). In these processes, sustainability research has become an established field of study, which raises questions about what the criteria are for becoming a member of a sustainability researcher community and who is a sustainability researcher. Our research adds to our understanding of who is engaging in sustainability questions and what kinds of perspectives are included (or excluded) in sustainability research.

Operationalizing sustainability researcher identity through ‘being’ and ‘doing’

Identity is a broad concept and a growing research field within social sciences (Côté 2006). It can be studied and approached with different theories depending on the discipline and goal of the research (Castelló et al. 2021; Ennals et al. 2016; Wilcock 1999). In short, identity as a concept gives a tool to explore and elaborate ‘the dynamic interplay over time of personal narratives, values and processes of identification with diverse groups and communities’ (McCune 2021). As a result, identity refers to the sense of self defined by psychological, physical and interpersonal characteristics including individual continuity and change over time, as well as social characterization and group affiliation (Castello et al. 2021).

Identity is also associated with one’s profession (Eteläpelto et al. 2013). Academic identity has been studied in relation to the various tasks and roles people have in academia, for example as a teacher and as a researcher, and the possible contradictions between them (Clegg 2008; Billot 2010; Dugas et al. 2020). It can also be considered from the perspective of the positionality of the researcher in the research field framing the research conducted (Cuevas-Garcia 2015). The basis of the academic identity is constructed through education providing epistemic views and competences, but also affected by personal values, motives and experiences (Ibarra et al. 2018; Winter 2009). Eteläpelto et al. (2013) have defined professional identity as the resource of agency at the individual level in addition to professional competences (e.g., knowledge), work experience, personal well-being and a sense of professional agency. Professional identity can relate to a special meaning especially in action-oriented sustainability research, where researchers may take a broader role than just an observer (see e.g., Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014) calling for acknowledging of researchers’ positionality and self-reflexivity (Popa et al. 2015; Wilson et al. 2022).

To build connections between the researcher identity and sustainability research, we utilize the conceptualization Wilcock (1999) originally created for a therapeutic occupation, which typically aims to combine theory and practice. According to Wilcock, engagement in occupations can be explained through four interacting dimensions, namely between being, doing, becoming and belonging (Ennals et al. 2016; Wilcock 1999). Doing is often used as a synonym for an occupation characterizing what is visible in professions. Being, in turn, encapsulates ‘nature and essence’, being true to oneself and one’s individual capacities. Accordingly, we suggest that being represents researchers’ inner aims and normative positions in sustainability research and guides the virtue of doing, which, in turn, concerns the actions, choices made in the actual research. On the other hand, we also hold that doing sustainability research is possible without being sustainability researchers. Doing and being are not only connected to each other but also to becoming and belonging. Becoming refers to the sense of the future, a possibility of a personal transformation, which has also been considered an important underlying dimension at least for some sustainability researchers acknowledging the self-reflexivity and inner transformation of sustainability researchers (Horlings et al. 2020).

All these aspects may contribute to the idea of belonging, referring to a (in)formal membership of a community/communities (Ennals et al. 2016). This is also an important aspect of sustainability research. Many sustainability researchers may have a disciplinary background in some specific fields, as sustainability science is only recently getting a formal position in the academic world. Many sustainability researchers may have a dual identity, for example as a geographer or sustainability scientist, being committed to promote sustainability transformation, and practicing inter- and transdisciplinarity. Another aspect related to belonging is that sustainable development and sustainability itself a study that is a cross-cutting strategic goal of many universities and research institutes (Soini et al. 2018), which makes it important to involve a wide group of researchers beyond sustainability scientists to understand how sustainability research identity and conceptualized are formed and interlinked.

Although all four of these modes of identity are relevant for sustainability research, we focus on being and doing due to the original research setting (see Chapter 3) but discuss the relevance of becoming and belonging in the formulation of sustainability researcher identity (see Chapter 5).

Dimensions of sustainability research and researcher identity

Following the previous discussion, we hypothesize that researcher identities are likely to be associated with different normative, epistemic and socio-political ways of being a researcher and doing research (Knaggård et al. 2018), and are further manifested through different research approaches and conceptualizations. Based on interviews with 28 key sustainability scientist researchers, Miller (2013) constructed a framework for sustainability science research and practice. The framework consists of three dimensions: normative, epistemic and socio-political (Table 1). The normative dimension refers to definitions of sustainability, the epistemic dimension refers to approaches to sustainability agendas and the socio-political dimension to the role of knowledge in society.

Many combinations of dimensions are possible, for example, the universalist definition and coupled-system approach seem to communicate well with the knowledge-first approach, as well as the procedural and social change approach with process-oriented knowledge production, illustrating two main orientations for sustainability science (Miller 2013). This division follows the descriptive-analytical, system-oriented way of conducting sustainability research and the more co-creative and solution-oriented way which are discussed in the current sustainability science literature (Lang et al. 2017; Lang and Wiek 2021).

The framework presented in Table 1 was originally created among sustainability science pioneers. Since its publication about ten years ago, sustainability has been mainstreamed in universities' and research institutes' strategies and is a crucial part of many research projects outside sustainability science and the work of researchers who are not educated sustainability scientists. Therefore, it is relevant to widen the understanding of the use of the different dimensions among researchers in general beyond strict sustainability experts. We use the concept of sustainability research instead of sustainability science to mark the aim of this study to expand understanding of conceptualizations beyond actual sustainability scientists to all research activities that concern sustainability.

Methods

This article is based on a study, which originally aimed to better understand the different conceptualizations of sustainability used by the researchers working in two research institutes in Finland. The reason for this study was the observation that sustainability was a key and overarching term used in the strategy of both institutes, as well as employed by several researchers, while understood in many ways. The study originally aimed to find out what were the most common ways to use and operationalize sustainability. The research strategy employed two phases: first to conduct a few interviews with researchers representing different disciplines, and then design a survey to be disseminated among all the researchers in these two institutes. The interviews pointed out that the issue of researcher identity was essential, something worthwhile to be considered, and to be tackled also by the survey, and sustainability research more broadly. Therefore, we integrated the question related to identity also in the survey. The article uses a mixed methods research strategy based on semi-structured interviews (N = 7) and survey data (N = 376). The survey included quantitative Likert-scale questions and an open-ended question about definitions of sustainability, which resulted in 133 answers analyzed as qualitative data. The relationship between these two bodies of data is reciprocal: The qualitative interviews informed the survey design but also helped explain and illustrate the survey results in more in-depth.

In the following sections, we will first describe the institutes where the research was conducted and after that the research material (interviews and survey) and methods more in depth.

Research institutes

The research was carried out in two public research institutes in Finland. The first public research institute defines its vision as “a sustainable future and well-being from renewable natural resources” and has a strategy that consists of programs and focus areas with sustainability as a cross-cutting theme. The institute has about 1300 employees, 50% of which are scientists. Besides research (70% of person months), the institute provides statutory and expert services (20%), statistical services (5%) and customer services (5%). Approximately 60% of its budget (75 million €) comes from the state budget and 40% (60 million €) from external funding, such as regional and structural funding, EU, the Academy of Finland and private companies.

The university consists of 11 faculties, has around 38,000 students and 8,200 employees. The strategic goals are divided into four areas: well-being for humans and our environment, a humane and fair world, a sustainable future for our planet, and the possibilities that limitless curiosity opens up—a universe of ideas and opportunities. Sustainability is the cross-cutting theme of the university in the new strategy (2021–2030). The university revenues (around 714 million euros) consist of around 58% core funding from the state, 40% external funding (Academy of Finland, Foundations, EU, Business Finland, Ministries, Companies, other sources) and 1.8% revenues generated by the university. The university has a sustainability science institute founded in 2018. The institute has over 500 members from nine faculties.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted in the summer and autumn of 2019. In total, seven interviews with the researchers were carried out to: (i) identify the key issues associated with the sustainability concept; (ii) reveal similarities and differences in definitions of the concept and its scope; and (iii) explain overall agreements and disagreements between researchers. Six interviews were conducted face-to-face, and one was received by email. The language of the interview was Finnish in five cases and English in two cases. The interview questions focused on the meaning of sustainability for the interviewee, the use of the dimensions of sustainability and perceived achievability of sustainability in society.

We searched for interviewees based on their research projects, publications and public profile that indicate they conduct sustainability research. Moreover, the interviewees were selected because their research areas, approaches and scientific backgrounds were different from each other, and enabled a versatile set of exploratory interviews. The purpose of the interviews was not to be a significant sample but to provide updated information about researchers’ engagement in the field of sustainability.

The themes of the interviews included: (1) what sustainability means to the society and the respondent in personal; (2) how does the respondent understand the concept of sustainability and its relations; (3) whether the respondent thinks that sustainability is achievable and why; (4) how the respondent’s own research relates to sustainability; (5) whether the respondent expects sustainability to affect their work in the future and how.

The results of the interviews were used to develop a larger survey that was supplemented by Miller (2013). The survey was designed to collect data on a bigger sample of researchers (see Sect. “Survey”). The survey included an open-ended question resulting in 133 qualitative answers. The open-ended question asked the respondent to give their own definition of sustainability after a set of statements related to pre-identified definitions.

Analysis of interviews and open-ended survey question

The qualitative material was analyzed thematically using Atlas.ti qualitative data analysis software. Three rounds of thematic coding were conducted, focusing on emerging themes in relation to definitions of sustainability (Gibbs 2018). Collected information was then classified according to different characteristics of the sustainability concept. The coding process was open to any emerging themes and did not apply a strict coding structure to be able to capture any unexpected or surprising aspects related to sustainability.

Survey

Participants

The survey was collected during 2020 through an online questionnaire at one large public research institute and one large university in Finland. The questionnaire was distributed to personnel email addresses, and it was also advertised on the intranet pages of the organizations. A total of 376 responses were received. It was possible to respond to the survey either in English or in Finnish. About 23% of the respondents were affiliated with the research institute and 77% were affiliated with the university. Of the respondents, about 54% were women. Around 44% of the respondents were between 34 and 51 years of age, 25% were 33 years or less and 31% were 52 years or older. The mean years of research experience in the sample was about 16 years (SD = 11.3). About 42% of the respondents represented natural sciences and medicine (including life sciences, physical sciences, mathematics, data science, computer science, medicine and pharmacy), about 35% represented social sciences and humanities (including humanities, theology, social science, economics, education, law and psychology) and about 23% represented agricultural sciences (including agriculture, forestry, agricultural and environmental economics and veterinary sciences). Of all the participants, only one reported the field of sustainability science as their specific research field.

Materials

The questions analyzed in this study were part of a larger survey that focused on sustainability research (see Supplementary Material 1 for questions analyzed in this study). The questions about the approaches and definitions of sustainability were operationalized using the definitions by Miller (2013) and measured with statements presented in Table 2 and qualitative interviews. If not otherwise mentioned, the response scale was a 7-point Likert scale (1 = disagree very strongly—7 = agree very strongly).

Respondents’ perception of themselves as a sustainability researcher (i.e. ‘being’) was measured with the question ‘do you think of yourself as a sustainability researcher?’ The response options were ‘no’ and ‘yes’. Respondents’ views on whether they did sustainability research (i.e. ‘doing’) was measured with a question about whether the respondent did sustainability research; the response options were ‘no’, ‘yes, but sustainability is not an essential part of my research’ and ‘yes, sustainability is an essential part of my research’.

In addition, the questions on how many years one has done research, research discipline, gender (woman, man, other, does not want to tell), age group and organization were included in the analyses.

Quantitative analysis of the survey

Variables measuring the conceptualizations of sustainability were formed using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation. PCA yielded six components with Eigenvalue over 1 (Table 3), which together explained 61.73% of the variation in the responses. The PCA corresponds fairly well to the six components of sustainability by Miller (2013). The component scores were saved as new variables to be used in further analyses.

The association between the question measuring researcher identity (a binary variable) and explanatory variables was tested with binary logistic regression. The association between the question measuring if a respondent did sustainability research (a categorical variable with three categories) and explanatory variables was tested with multinomial logistic regression. The association between researcher identity and doing sustainability research was tested with a cross-tabulation and Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

Results

Identifying oneself as a sustainability researcher

The qualitative interviews revealed a difference between being and doing, i.e., defining oneself as a sustainability researcher or a researcher who does sustainability research. The research work of every interviewee in this study was related to sustainability in diverse ways. Despite this, interviewees did not necessarily see themselves as sustainability researchers. This was reflected in statements indicating insecurity regarding the relationship between ‘being’ and ‘doing’ sustainability research: ‘It is interesting but not the main issue to follow because I’m not a sustainability researcher in my own opinion’.

The interviewees were not specifically asked to reflect on whether they considered themselves sustainability researchers or representatives of another scientific discipline. Still, some of them spontaneously wanted to define themselves either at the beginning of the interview or when it came to the question about how sustainability is reflected in their own work. These interviewees showed primary connectedness to their scientific background. ‘I am an economist […]’ or ‘As a researcher in legal fields, I examine sustainability from the legal system’.

The interviewees, whose scientific background did not come up in the interviews, did not explicitly call themselves sustainability researchers. This was the case even if the research work of these interviewees seemed to be intertwined with sustainability issues. ‘In terms of research, I haven’t been directly involved, but everything has to do with [sustainability]’. It seems that the interviewees defined sustainability research specifically as developing, using or analyzing the concept or methods of sustainability—not as the study of sustainability itself: ‘I have never used [sustainability] as an analytical concept, but it has always been about improving it [sustainability]’.

The survey data show divisions between ‘being’ a sustainability researcher or ‘doing’ sustainability research. The cross-tabulation of the questions about doing sustainability research and thinking of oneself as a sustainability researcher indicated that doing sustainability research was positively associated with thinking of oneself as a sustainability researcher (Pearson χ2 = 115.51, p < 0.001) (Table 4). However, doing sustainability research and thinking of oneself as a sustainability researcher were only partly overlapping with each other. For example, about 7% of the respondents did sustainability research and considered sustainability as an essential part of their research but did not think of themselves as sustainability researchers and about 4% of the respondents did not do sustainability research but thought of themselves as sustainability researchers.

Approaches and definitions of sustainability across different groups

Survey

The binary logistic regression model was used to test the associations between the perception of oneself as a sustainability researcher and the approaches and definitions of sustainability (Table 5). Those who thought of themselves as sustainability researchers were more likely to agree with the normative universalist and normative procedural definitions of sustainability. In addition, those who thought of themselves as sustainability researchers were more likely to agree with the epistemic coupled-system approach and less with the socio-political knowledge-first role than those who did not think of themselves as sustainability researchers. Those who thought of themselves as sustainability researchers were also slightly older than those who did not think of themselves as sustainability researchers.

The multinomial regression model was used to test the associations between doing sustainability research and approaches and definitions of sustainability (Table 6). Those who did sustainability research but to whom sustainability was not an essential part of their research were used as the reference group. Those who did not do any sustainability research were less likely to agree with the normative universalist and the normative procedural definitions of sustainability than those who did sustainability research but to whom sustainability was not an essential part of their research. In addition, those who did not do any sustainability research were more likely to agree with the knowledge-first role and less with the process-oriented role than those who did sustainability research but to whom sustainability was not an essential part of their research. Those who did sustainability research but to whom sustainability was not essential were more likely to be between 34 and 51 years old, and those who did not do any sustainability research were more likely to be less than 34 years old. Moreover, those who did no sustainability research had slightly fewer years of research experience than those who did sustainability research but to whom sustainability was not essential.

Those to whom sustainability was an essential part of their research were more likely to agree with the epistemic coupled-systems approach than those to whom sustainability was not essential. Moreover, those to whom sustainability was essential were less likely to agree with the socio-political knowledge-first role than those to whom sustainability was not essential.

Qualitative data on conceptualizations of sustainability

The analysis of the qualitative material confirms the plurality that is related to definitions of sustainability. Analysis of the freely given definitions for sustainability shows multiple definitions among both researchers who defined themselves as sustainability-related scientists and those who did not consider themselves to work in sustainability (Table 7). Many of the respondents between both groups emphasize the same aspects of sustainability, such as balance; the well-being of humans, non-humans and cross generations; and natural resources.

There was a greater variety of definitions given among researchers who consider themselves sustainability researchers. These additional themes to ‘non-sustainability researchers’ included more specifically different societal processes such as peace, education, attitude and lifestyle changes and even inner aspects such as consciousness and feeling oneness with nature. This may indicate more holistic views on sustainability and the recent orientation to transformative sustainability research. It is notable that the most emphasized aspects of the given definitions were already included in the statements in the survey. Yet these aspects were rephrased with their own words in the open question in which researchers tended to frame their perspective from the viewpoint of their disciplinary background (e.g., focusing on natural resource use).

Based on the semi-structured interviews, four rough views on conceptualizations of sustainability could be identified.

The first position relates to dimensional definitions of sustainability including social, ecological, economic and sometimes culture. These dimensions were not considered as equal pillars, but greater weight was given to the ecological component. In this view, the approach to sustainability seems rather pragmatic and even critical to the further development of the concept as the following quote illustrates:

‘(…) holistic sustainability sounds mad to me. As some kind of tree-hugging, it sounds weird to an economist. Sustainability as a concept emphasizes comprehensiveness. You do not need to repeat it by talking about holistic sustainability’.

The second position emphasizes sustainability as a process but also refers to the social, economic and ecological dimensions: ‘It is a temporal process that aims at shifting a system to another, more desirable state’.

The third position emphasizes sustainability as a process as well but adopts a critical position to conceptualize sustainability through dimensions. Here, other aspects of sustainability such as societal processes and preferences are emphasized in the discussion of sustainability as well as other concepts such as resilience and transformations: ‘Why should we list 4–6 dimensions when we are anyway aiming at holistic sustainability […] I am against dimensions but when we talk about sustainability we need to talk about something concrete […] Any time we look beyond nature [to social issues] we need to think of what we are actually talking about. […]’.

Criticality towards the use of the concept of sustainability can be identified as the fourth approach. This includes a view that sustainability is a vague concept that is used too often so that it loses its meaning. The interviewee phrases: ‘I am critical towards using the concept because it is used so often. It is used lightly and without thinking. It is extremely difficult to say that something is sustainable if you consider both environment and human perspectives at different times and scales. People value sustainability differently’.

Discussion

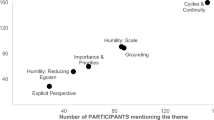

Our results demonstrate the link between different researcher identities and preferred approaches and definitions of sustainability. However, they also illustrate how the different approaches are not contradictory but rather complementary, demonstrating nuances in the preferred emphasis among researchers (Miller 2015). Sustainability researchers need to be able to adopt different approaches and definitions depending on the questions and problems studied but also depending on people involved in inter- and transdisciplinary collaborations (Cuevas-Garcia 2015; Soininen et al. 2022). Figure 1 presents a heuristic model with guiding questions to reflect the relationships between identity and the chosen approaches and definitions to sustainability that researchers may employ to start to assess their underlying assumptions regarding sustainability-related research. The needed flexibility of epistemological stances within sustainability research (Haider et al. 2018) might challenge a formulation of a strong disciplinary identity. On the other hand, a sustainability researcher identity might be more easily adopted by researchers who are willing to execute this reflexive flexibility and epistemic agility in their work. Our explorative research provides a starting point to consider these emerging questions in the field of sustainability.

Sustainability researchers’ identity through ‘doing’ and ‘being’

We operationalized researcher identity through the notions of ‘being’ a sustainability researcher and ‘doing’ sustainability research. Our results show that the relationship between conducting (doing) sustainability research and considering oneself a sustainability researcher (being) is not straightforward. While most researchers simultaneously identified themselves as sustainability researchers and did sustainability-related research (being & doing), there were also researchers who did sustainability research without considering themselves as sustainability researchers (doing) and vice versa (Table 4). The qualitative interviews indicated that being a sustainability researcher is not necessarily always desired by some researchers even though they would do sustainability research through their occupation, highlighting the different identities gained through ‘being’ and ‘doing’ (Ennals et al. 2016; Wilcock 1999). In these cases, sustainability was most likely approached from one’s disciplinary point of view, and there was a sense of resistance towards other conceptualizations of sustainability. Hence, this suggests that sometimes there can be an intentional gap between ‘doing’ sustainability research and ‘being’ a sustainability researcher, which adds to the epistemic plurality of sustainability-related research and may affect attitudes with practical implications in inter- and transdisciplinary collaborations (Guimarães et al. 2019; Spoelstra 2013). However, due to the normativity and epistemic plurality in sustainability research that is not bound to disciplinary identities (Hakkarainen et al. 2021), sustainability researcher identity can also function as a lever away from strict disciplinary identities.

In our survey sample, most respondents were not affiliated formally with sustainability science institutes or considered their research field to specifically be sustainability science (one respondent named sustainability science as their field). This can be explained by the relatively recent increase in formal education in sustainability science (Salovaara et al. 2020), which means that many people engaging with sustainability research are not trained sustainability scientists and do not have a formal identity as sustainability researchers. This does not, however, mean that they could not conduct sustainability research. Nevertheless, any of the respondents still considered themselves sustainability researchers, indicating that a sustainability researcher identity might be particularly fluid and dynamic (Castello et al. 2021) compared to research fields that have a less crosscutting and interdisciplinary edge. It can be easy to adopt as it is not necessarily dependent on institutional aspects or labels, such as degree or affiliation or a specific discipline. Interdisciplinary approaches and capacities are considered to be further strengthened among sustainability scientists (Schoolman et al. 2012; Soininen et al. 2022), which might contribute to identity-building among researchers in that field and call for stronger institutional support. However, stronger institutionalization of sustainability research in the form of sustainability science in turn may lead to a situation that researchers who are not fully embedded in the field do not dare to take ‘the hat’ of sustainability scientist.

‘Being’ and ‘doing’ in relation to dimensions of sustainability research

The results related to approaches and definitions of sustainability illustrate the heterogeneity within sustainability research. The researchers who considered themselves sustainability researchers (‘being’) were more likely to agree on the normative universalist definitions and procedural definitions of sustainability, as well as the epistemic coupled-systems approach than the researchers who did not consider themselves to be sustainability researchers. In turn, those who did not consider themselves sustainability researchers agreed more with the socio-political knowledge-first role than those who considered themselves sustainability researchers. These findings indicate that systems thinking and analytical understanding of systems dynamics within sustainability research is still a strong paradigm despite the proposed shift towards more process-oriented, co-creative and relational approaches (West et al. 2020). Differences were not detected in the prominence of the epistemic social change approach between those who considered themselves sustainability researchers and those who did not.

Normative universalist definition was gradually more emphasized by the researchers who did not work with sustainability-related research and by the researchers who worked with sustainability research but did not consider sustainability an essential part of their research compared to the researchers to whom sustainability was an essential part of their research (‘doing’). Moreover, those to whom sustainability was an essential part of research agreed more with the normative procedural definitions of sustainability than those who did sustainability research but to whom it was not an essential part of the research. Universalist definition presents a more conventional approach to sustainability research when compared to more procedural and transformative modes that have been adopted through collaborative and transdisciplinary approaches to sustainability research (Horcea-Milcu et al. 2020). Moreover, those who did sustainability research aligned more with the socio-political process-oriented role than those who did not do any sustainability research. The noted differences in data may indicate that the procedural and process-oriented variants of sustainability research relating more to the collaborative approaches in sustainability research (e.g., Chambers et al. 2021) have not been largely adopted in research communities outside sustainability science. However, both these modes are still recognized as prominent even within sustainability science, in which it is crucial to build bridges between the different approaches (Lang and Wiek 2021).

Similarly, the qualitative analysis of the survey responses demonstrated the variety of definitions among respondents who considered themselves sustainability researchers and those who did not (Table 7). The most repeated themes were similar among both groups, which indicates that common definitions of sustainability are widely shared and applied. Yet, more themes could be identified in the responses of sustainability researchers (being), which showcases the great diversity of conceptualizations of sustainability even within sustainability research experts (Miller 2013). This was also reflected in the interviews that showed a variety of approaching sustainability in research. Among sustainability-oriented researchers there are the researchers who are most embedded in the sustainability field and therefore more likely to first take up new ideas and theories related to sustainability. The results advance understanding of sustainability science outlined by Miller (2013) by also considering researchers’ perceptions of sustainability outside the sustainability science field. However, alongside the increasing use (and misuse) of the concept of sustainability (Waas et al. 2011), the desirability of using the concept might decrease among those invested in sustainability-related research.

Implications for sustainability research

Sustainability in current research is a cross-cutting theme not limited to those who have been formally trained in sustainability science. Therefore, sustainability-related research is and will be characterized by a diversity of researcher identities. When sustainability science as a field develops methodologically and theoretically, it could be expected that the new framings trigger the rest of academia. However, as shown in this study, researcher identities might remain discipline-specific, which could affect how newer approaches within sustainability science such as co-creative, relational and process-oriented modes of knowledge production (Norström et al. 2020; Turnhout et al. 2020; West et al. 2020) that challenge researchers' roles and identities as objective observers are accepted as a valid way to produce knowledge in wider academia. Sustainability research and sustainability science need to acknowledge and deal with diversity related to definitions of and approaches to sustainability (Blythe et al. 2017).

The lack of a physical environment in the forms of sustainability science institutes might also create a barrier to forming a sustainability researcher identity. Formal sustainability science education could contribute to identity building through enabling ‘becoming’, and through physical spaces and institutes formed around sustainability research supporting ‘belonging’ to a group of people with similar interests. In addition to ‘belonging’ fostered through social recognition, belonging can be linked to the material resources that enable the developing and applying of their knowledge-related expertise (Montana 2021). As Ennals et al. (2016) discuss, belonging as a way to form identity supports doing, being and becoming. However, because of the versatility of the sustainability concepts as illustrated in this study, founding sustainability science institutes require discussion on the diverse framings but also the identities touching upon questions, such as what sustainability research is and who can be considered a sustainability researcher. When sustainability is placed at the center of agendas at universities, this discussion reaches beyond those explicitly ‘doing’ sustainability research or ‘being’ sustainability researchers to all research work in general. One of the key issues in sustainability research has been the diversity of ways sustainability has been conceptualized, leading to a need to navigate and reconcile the different views while still maintaining the epistemic plurality (Hakkarainen 2022). The results open up the discussion on interlinkages of identity, positionality and reflexivity (Wilson et al. 2022) in sustainability research and understanding researcher identity that can be used for facilitating communication across researchers from different scientific disciplines engaging with sustainability.

Limitations and future research

There are some limitations that need to be considered in making the conclusion from the results. First, the number of qualitative interviews was small; therefore, it is possible that the themes identified in the interviews were not exhaustive. However, the interviews complemented existing literature in the development of survey questions. In addition, the qualitative interviews guided studying the relationship between researcher identities and conceptualizations of sustainability. Second, the survey sample was not representative, and therefore, it is likely that researchers interested in sustainability are overrepresented in the data set. In addition, the survey questions used for measuring conceptualizations of sustainability were not based on previously validated scales because, as far as we know, such scales do not exist. We also acknowledge that to better align the survey items to measure the social change dimensions, our scale should have included a statement about perceptions of action-oriented research. However, the discussions around sustainability would greatly benefit from valid scales to measure conceptualizations of sustainability. The findings of the current study can be used for developing these scales.

Conclusions

This study aimed to identify connections between diverse dimensions of sustainability research and researcher identity among researchers within and outside the sustainability research field. We used Miller’s (2013, 2015) framework of different approaches and definitions of sustainability research. We related the framework to researcher identity that was operationalized through the notions of ‘doing’ sustainability research and ‘being’ a sustainability researcher. Using semi-structured interviews and a survey sent to two big research institutes in Finland, we could identify some connections between preferred dimensions of sustainability research and researcher identity. However, we emphasize that the different approaches to and definitions of sustainability are not contradictory. Our findings contribute to the discussion about sustainability researcher identity, which is increasingly important when sustainability is mainstreamed into many fields of research. Identity offers one lens to increase reflexivity through understanding differing perspectives and aims that shape how research is conducted and what is achieved with it. These themes could be further unpacked in practical research projects to also understand how researchers with different relationships to sustainability, and possibly from different disciplines, come together to develop tools to work in research environments of diverse views and positions towards sustainability. It becomes increasingly important to understand tensions and power relationships between researchers and disciplines when sustainability research is undertaken among multiple disciplines.

References

Adger WN (2006) Vulnerability. Glob Environ Change 16(3):268–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006

Billot J (2010) The imagined and the real: identifying the tensions for academic identity. High Educ Res Dev 29(6):709–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.487201

Blythe J, Nash K, Yates J, Cumming G (2017) Feedbacks as a bridging concept for advancing transdisciplinary sustainability research. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 26–27:114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.05.004

Castelló M, McAlpine L, Sala-Bubaré A, Inouye K, Skakni I (2021) What perspectives underlie ‘researcher identity’? A review of two decades of empirical studies. High Educ 81(3):567–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00557-8

Chambers JM, Wyborn C, Ryan ME, Reid RS, Riechers M, Serban A, Pickering T (2021) Six modes of co-production for sustainability. Nat Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00755-x

Côté J (2006) Identity studies: how close are we to developing a social science of identity? An appraisal of the field. Identity 6(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532706xid0601_2

Cuevas-Garcia CA (2015) ‘I have never cared for particular disciplines’—negotiating an interdisciplinary self in biographical narrative. Contemp Soc Sci 10(1):86–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2014.974664

Cutter S, Barnes L, Berry M, Burton C, Evans E (2008) Community and regional resilience: perspectives from hazards, disasters, and emergency. Washington DC

Dryzek JS (2013) The politics of the earth. Environmental discourses. Oxforford University Press

Dugas D, Stich AE, Harris LN, Summers KH (2020) ‘I’m being pulled in too many different directions’: academic identity tensions at regional public universities in challenging economic times. Stud High Educ 45(2):312–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1522625

Ennals P, Fortune T, Williams A, D’Cruz K (2016) Shifting occupational identity: doing, being, becoming and belonging in the academy. High Educ Res Dev 35(3):433–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107884

Eteläpelto A, Vähäsantanen K, Hökkä P, Paloniemi S (2013) What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educ Res Rev 10(December):45–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Gallopín GC (2006) Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob Environ Change 16(3):293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004

Gibbs GR (2018) Analyzing qualitative data. Sage Publication, London

Guimarães MH, Pohl C, Bina O, Varanda M (2019) Who is doing inter- and transdisciplinary research, and why? An empirical study of motivations, attitudes, skills, and behaviours. Futures 112(5):102441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2019.102441

Haider LJ, Hentati-Sundberg J, Giusti M, Goodness J, Hamann M, Masterson VA, Sinare H (2018) The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sustain Sci 13(1):191–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0445-1

Hakkarainen V (2022) Towards inclusivity in ecosystem governance: the epistemic dimension of human-nature connections and its implications for sustainability science. University of Helsinki. Unigrafia, Helsinki. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-8004-9

Hakkarainen V, Amato DD, Jämsä J, Soini K (2021) Transdisciplinary research in natural resources management : towards an integrative and transformative use of co-concepts. Sustain Dev. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2276

Hammack PL (2015) Theoretical foundations of identity. In: McLean KC, Syed M (eds) The Oxford handbook of identity development. Oxford University Press, pp 11–30

Hilger A, Rose M, Wanner M (2018) Changing faces-factors influencing the roles of researchers in real-world laboratories. Gaia 27(1):138–145. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.27.1.9

Horcea-Milcu AI, Abson DJ, Dorresteijn I, Loos J, Hanspach J, Fischer J (2018) The role of co-evolutionary development and value change debt in navigating transitioning cultural landscapes: the case of Southern Transylvania. J Environ Plan Manag 61(5–6):800–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1332985

Horcea-Milcu AI, Martín-López B, Lam DPM, Lang DJ (2020) Research pathways to foster transformation: Linking sustainability science and social-ecological systems research. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11332-250113

Horlings LG, Nieto-Romero M, Pisters S, Soini K (2020) Operationalising transformative sustainability science through place-based research: the role of researchers. Sustain Sci 15(2):467–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00757-x

Ibarra C, O’Ryan R, Silva B (2018) Applying knowledge governance to understand the role of science in environmental regulation: the case of arsenic in Chile. Environ Sci Policy 86(January):115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.05.002

Kajikawa Y, Tacoa F, Yamaguchi K (2014) Sustainability science: the changing landscape of sustainability research. Sustain Sci 9(4):431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0244-x

Kates RW (2011) What kind of a science is sustainability science? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(49):19449–19450. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1116097108

Kates RW et al (2001) Sustainability science. Science 292(5517):641–642

Knaggård Å, Ness B, Harnesk D (2018) Finding an academic space: reflexivity among sustainability researchers. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10505-230420

Lang DJ, Wiek A (2021) Structuring and advancing solution-oriented research for sustainability: this article belongs to Ambio’s 50th Anniversary Collection. Theme: solutions-oriented research. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01537-7

Lang DJ, Wiek A, von Wehrden H (2017) Bridging divides in sustainability science. Sustain Sci 12(6):875–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0497-2

Lundgren J (2021) The grand concepts of environmental studies boundary objects between disciplines and policymakers. J Environ Stud Sci 11(1):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-020-00585-x

McCune V (2021) Academic identities in contemporary higher education: sustaining identities that value teaching. Teach High Educ 26(1):20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1632826

Miller TR (2013) Constructing sustainability science: emerging perspectives and research trajectories. Sustain Sci 8(2):279–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-012-0180-6

Miller TR (2015) Reocnstructing sustainability science: knowledge and action for a sustainable future. Earthscan, London and New York

Montana J (2021) From inclusion to epistemic belonging in international environmental expertise: learning from the institutionalisation of scenarios and models in IPBES. Environ Sociol 7(4):305–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2021.1958532

Nagatsu M, Davis T, DesRoches CT, Koskinen I, MacLeod M, Stojanovic M, Thorén H (2020) Philosophy of science for sustainability science. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00832-8

Norström AV, Cvitanovic C, Löf MF, West S, Wyborn C, Balvanera P, Österblom H (2020) Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2

Popa F, Guillermin M, Dedeurwaerdere T (2015) A pragmatist approach to transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: from complex systems theory to reflexive science. Futures 65:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2014.02.002

Purvis B, Mao Y, Robinson D (2019) Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain Sci 14(3):681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

Salas-Zapata WA, Ortiz-Muñoz SM (2019) Analysis of meanings of the concept of sustainability. Sustain Dev 27(1):153–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1885

Salovaara JJ, Soini K, Pietikäinen J (2020) Sustainability science in education: analysis of master’s programmes’ curricula. Sustain Sci 15(3):901–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00745-1

Schoolman ED, Guest JS, Bush KF, Bell AR (2012) How interdisciplinary is sustainability research? Analyzing the structure of an emerging scientific field. Sustain Sci 7(1):67–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0139-z

Scoones I (2007) Sustainability. Dev Pract 17(4–5):589–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469609

Shahadu H (2016) Towards an umbrella science of sustainability. Sustain Sci 11(5):777–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0375-3

Slager R, Pouryousefi S, Moon J, Schoolman ED (2020) Sustainability centres and fit: how centres work to integrate sustainability within business schools. J Bus Ethics 161(2):375–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3965-4

Soini K, Jurgilevich A, Pietikäinen J, Korhonen-Kurki K (2018) Universities responding to the call for sustainability: a typology of sustainability centres. J Cleaner Prod 170:1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.228

Soininen N, Raymond CM, Tuomisto H, Ruotsalainen L, Thorén H, Horcea-Milcu AI, Nagatsu M (2022) Bridge over troubled water: managing compatibility and conflict among thought collectives in sustainability science. Sustain Sci 17(1):27–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-01068-w

Spoelstra SF (2013) Sustainability research: organizational challenge for intermediary research institutes. NJAS Wageningen J Life Sci 66:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2013.06.002

Turnhout E, Metze T, Wyborn C, Klenk N, Louder E (2020) The politics of co-production: participation, power, and transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 42(2018):15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009

Waas T, Hugé J, Verbruggen A, Wright T (2011) Sustainable development: a bird’s eye view. Sustainability 3(10):1637–1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su3101637

Web of Science (2021) https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search. Accessed Mar 2021

West S, Haider LJ, Stålhammar S, Woroniecki S (2020) A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst People I. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417. (in press)

Wiek A, Withycombe L, Redman CL (2011) Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustain Sci 6(2):203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6

Wilcock AA (1999) Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Aust Occup Ther J 46(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x

Wilson C, Janes G, Williams J (2022) Identity, positionality and reflexivity: relevance and application to research paramedics. Brit Paramed J 7(2):43–49. https://doi.org/10.29045/14784726.2022.09.7.2.43

Winter R (2009) Academic manager or managed academic? Academic identity schisms in higher education. J High Educ Policy Manag 31(2):121–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800902825835

Wittmayer JM, Schäpke N (2014) Action, research and participation: roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain Sci 9(4):483–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0258-4

Wuelser G (2014) Towards adequately framing sustainability goals in research projects: the case of land use studies. Sustain Sci 9(3):263–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0236-2

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Natalia Kuosmanen for her contribution to the planning and data collection of this paper. We are also grateful for all the researchers who participated in this research, either as an interviewee or respondent in the survey. The comments of the two anonymous reviewers and the editor were extremely helpful to clarify the research process, some of the concepts used, as well as interpretation of the results. We are grateful for them.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital. This study was funded by Natural Resources Institute Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handled by Thaddeus Miller, University of Massachusetts, United States.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hakkarainen, V., Ovaska, U., Soini, K. et al. ‘Being’ and ‘doing’: interconnections between researcher identity and conceptualizations of sustainability research. Sustain Sci 18, 2341–2355 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-023-01364-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-023-01364-7