Abstract

Reflecting on teaching experience is meaningful in teacher education because it enables student teachers to evaluate their professional behaviours in the classroom and to develop new instructional strategies. Little is known, however, about the motivational aspects of the reflection process, such as self-efficacy for reflection. Self-efficacy is an important resource in teacher education which relates negatively to stress and burnout, and positively to professional behaviour. This longitudinal intervention study with data from N = 600 student teachers investigates how self-efficacy for reflection can be enhanced over the course of one semester. Our findings show that student teachers’ self-efficacy increased significantly in an intervention group in which student teachers systematically reflected on teaching situations in the context of micro-teaching experiences. There was no increase in self-efficacy in the control group in which student teachers did not teach in schools, nor systematically reflect. The increase in self-efficacy for reflection in the intervention group was moderated by previous pedagogical experiences in teaching of student teachers. Our findings are discussed for further development in teacher training.

Zusammenfassung

Die Reflexion von Unterrichtserfahrungen ist in der Lehrkräftebildung von hoher Bedeutung, da sie es den Lehramtsstudierenden ermöglicht, ihr professionelles Verhalten im Unterricht zu bewerten und neue Unterrichtsstrategien zu entwickeln. Es ist jedoch wenig über die motivationalen Aspekte des Reflexionsprozesses bekannt, wie z. B. die reflexionsbezogene Selbstwirksamkeit. Selbstwirksamkeit ist eine wichtige Ressource in der Lehrerkräftebildung, die sich negativ auf Stress und Burnout und positiv auf professionelles Verhalten auswirkt. Diese längsschnittliche Interventionsstudie mit Daten von N = 600 Lehramtsstudierenden untersucht, wie die reflexionsbezogene Selbstwirksamkeit im Laufe eines Semesters verbessert werden kann. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die Selbstwirksamkeit von Lehramtsstudierenden in der Interventionsgruppe, die im Kontext von Microteaching Erfahrungen Unterricht systematisch reflektierten, signifikant anstieg. In der Kontrollgruppe, in der die Lehramtsstudierenden weder in Schulen unterrichteten noch systematisch reflektierten, war keine Zunahme der Selbstwirksamkeit zu verzeichnen. Der Anstieg der Selbstwirksamkeit in der Interventionsgruppe wurde durch pädagogische Vorerfahrungen im Unterrichten moderiert. Unsere Ergebnisse werden für die Weiterentwicklung der Lehrkräftebildung diskutiert.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Reflective processes are a key concern of educational research because reflection is assumed to lead (student) teachers to reflect on their own beliefs about effective teaching, and, through this, improve their teaching in practice (Schön 1987; Rahm and Lunkenbein 2014). Whereas the importance of reflection for the development of professional competence in schools has been widely discussed in theoretical and empirical work (e.g., Babaei and Abednia 2016; Richter et al. 2022; Weß et al. 2017), there is a lack of research on the motivational aspects of reflective processes. It is currently not well understood to what extent self-efficacy for reflection can be promoted through micro-teaching experiences and by systematic reflection on teaching situations during teacher training. Kulgemeyer et al. (2021) for example assumed that student teachers who enter the practical semester with a higher capacity for reflection, are more successfully able to develop their professional knowledge, didactic knowledge and pedagogical knowledge based on their practical experience. The present study addresses this gap by investigating how self-efficacy for reflection developed over the course of one semester. We compared the change in self-efficacy for reflection in an intervention group in which student teachers systematically reflected on videotaped or protocol-based teaching experiences, and in a control group in which systematic reflection and micro-teaching experiences did not take place. Assuming that mastery experiences are an important source of self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura 1997), we also examined how prior pedagogical practice in schools was associated with changes in student teacher self-efficacy for reflection. Our findings inform educational research about the changes in student teachers self-efficacy beliefs in the area of reflection and about the role of systematic reflection in enhancing student teacher’s self-efficacy for reflection.

2 Reflection on teaching practice

On a conceptual level, reflective thinking has been defined as the conscious and aimed reflection which involves a) a state of doubt or mental difficulty, in which thinking arises and b) an act of searching and investigating to find material that removes doubt, clarifies and eliminates perplexity (Dewey 1933). In this theoretical context, reflection has been described as a mental process that includes the structuring or restructuring of insights, experiences, problems, or existing knowledge (Korthagen et al. 2001). Schön (1987) differentiated between reflection-on-action and refection-in-action. Reflection-in-action referring to spontaneously arising actions in the classroom which prompt a reframing of the situation which happens automatically and affects teaching behaviour during the situation at hand (Schön 1987). This kind of reflection, however, presupposes pedagogical experience and is therefore not suitable for novices (Hatton and Smith 1995). In contrast, reflection-on-action is an intentional process initiated after a teaching situation in which an unexpected situation appeared during the routine action, prompting the practitioner to reconsider his or her actions after the situation in order to develop adaptive behaviours for future teaching actions (Schön 1987). Therefore, reflection-on-action can be stimulated by different actions, for example research describes reflection-generating activities that refer to actions that initiate reflective processes such as the discussion of case studies, writing journal entries, or audio- or video-recordings and analysing of lessons in teacher education and teaching practice (Jaeger 2013). In this process, pre-service teachers or teachers take on the role of a reflective practitioner (Schön 1987) because their teaching practice is reflected upon/on.

Kleinknecht and Gröschner (2016) suggest three steps of the process of reflection and refer to literature on professional vision (e.g., Seidel and Stürmer 2014): (1) describe (2) evaluate and explain and (3) develop alternative teaching strategies to improve the teaching practice. The concept of reflection and the concept of professional vision are theoretically linked. For example, the identification of relevant situations in the teaching process, labelled as ‘noticing’ in professional vision, can be seen as a key requisite for the first step of reflection (describing). The process of knowledge-based explanations of teaching situations (reasoning) in professional vision (Sherin and Van Es 2009) is theoretically close to the second step in the reflection process (evaluate and explain). However, a clear distinction between both concepts is that reflection includes the critical thinking about own explanations and the development of alternative actions (step 3: develop alternative teaching strategies) (vgl. Hatton and Smith 1995), which is not part of professional vision.

In our study, we focus on reflection-generating activities, in our case the reflection of the taught lessons in the class using videos or protocols, that include the three steps of reflection. Thus, our work refers to reflection-on-action rather than to reflection-in-action.

3 Motivational aspects of reflection: self-efficacy for reflection and its sources

Self-efficacy beliefs are a central aspect of motivational processes (Bandura 1997) and in context of teacher education it has been defined as a judgment of one’s own capabilities to bring about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning, even when experiencing challenges (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy 2001). This definition has also been relied upon in research involving student teachers (Eisfeld et al. 2020; Hußner et al. 2022). In addition to the global self-efficacy facets, specific facets of self-efficacy beliefs are also distinguished in recent research (e.g., teacher self-efficacy for classroom management etc.). Self-efficacy for reflection can be understood as the belief of being able to overcome challenging reflections on the basis of one’s own abilities (Lohse-Bossenz et al. 2019). To our knowledge, recent research has not investigated the role of self-efficacy for reflection for student teachers’ professional development during teacher education. Therefore, previous results about the effects of general (rather than reflection-related) self-efficacy are reviewed here. However, because general self-efficacy relates to competence beliefs in regard to teaching and school-related tasks, the findings of these studies can only provide preliminary assumptions for the construct of student teacher self-efficacy for reflection.

Referring to socio-cognitive theory (Bandura 1989), the four sources of self-efficacy beliefs are mastery experiences (own teaching experiences), vicarious experiences (observing teaching of other’s), verbal persuasion (feedback) and physiological and affective states (arousal in situations where the ability in the area concerned is demonstrated) (cf. Morris et al. 2017). Applied to the context of teaching, important sources of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs are own practical experiences (mastery experiences) as strongest source of self-efficacy—for example in schools—and the observation of expert teachers in classrooms (vicarious experiences) which also has been empirically analysed for pre-service teachers in context of teacher education program (Martins et al. 2015). In the context of reflection processes, examples for vicarious experiences could be the observation of others in their process of reflection, happening for example in collegial case supervision (Strieker et al. 2016). Verbal persuasion in the context of reflections could be when student teachers are provided with feedback on their verbal or written reflections (Murphy and Ermeling 2016).

Prior research, however, is inconclusive. Some studies showed an increase in self-efficacy of student teachers after practical phases (Eisfeld et al. 2020; Ronfeldt and Reininger 2012). Other findings indicated that student teachers’ self-efficacy does not increase in practical phases in which student teachers did not teach a lot (Schüle et al. 2017). Therefore, the design (duration, scope) of the practical phase may be crucial for its effectiveness. When student teachers have the chance to teach and reflect on their own teaching experiences in classrooms during school internships in teacher education, self-efficacy for reflection increases during the semester (Hußner et al. 2022). An open question is whether student teachers’ self-efficacy also increases during their university studies when no practical phases are involved. Research suggests that particularly in the first semester of their studies, self-efficacy of student teachers increases even without practical experiences (Lamote and Engels 2010). Taken together, it might be assumed that student teachers’ self-efficacy increases during their studies—particularly after a practicum or with the help of vicarious experiences through case studies.

If real-life experiences cannot be provided in teacher education, there might be other learning opportunities that contribute to an increase in student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection. One factor might be pedagogical experiences that student teachers have outside of university. The daily social interactions that are related to such prior pedagogical experiences of (student) teachers initiate reflection processes about these micro-level interactions which then shape subsequent reflection processes and the own competence in relation to that process (Fend 1998; Wyss 2008). However, studies usually examine the role of prior pedagogical experiences for general—and not reflection-specific—self-efficacy of teachers. For example, findings show that student teachers with prior pedagogical experiences report a lower perceived increase in competence with regard to professional activities as a teacher (Cramer 2012). However, knowledge is missing about the role that prior teaching experiences might play in the context of competence beliefs about reflection of teaching. Another option to gain pedagogical experiences more indirectly is the reflection of classroom videos. The reflection of such videos is expected to be an enhancer of a positive development of student teachers’ and teachers’ self-efficacy (Gold et al. 2017; Naidoo and Naidoo 2021). On a theoretical level, the videotaped observation of own teaching behaviour might be a source of self-efficacy beliefs in the sense of mastery learning (Gold et al. 2017). Research, accordingly, showed a positive trend of changes in teacher self-efficacy in a group of teachers that based on videos reflected their own or another teachers’ classroom behaviours compared to teachers who exchanged their experiences, but did not reflect on their own or others’ teaching based on videos (Gröschner et al. 2018). Moreover, in context of education programs, results of Karsenti and Collin (2011) showed that pre-service teachers who learned with simulated video recordings increased their self-efficacy assessed by the adapted scale of Friedman and Kass (2002).

4 Self-Efficacy for reflection and individual characteristics of (student) teachers

Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986) describes that individual and learning environmental factors have an effect on behaviour and development. Student teachers’ individual characteristics may therefore influence the extent to which student teachers benefit from learning opportunities (see also Voss et al. 2017). Given that mastery experience is an important source of self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura 1997)—which is also true for the teaching context (e.g. Pfitzner-Eden 2016b)—it is assumed that prior teaching performances in teaching have a positive effect on self-efficacy beliefs of teachers. Empirical evidence accordingly showed that prior educational experiences in private or professional contexts had an important and positive effect on preservice teachers’ self-efficacy (Bruinsma and Jansen 2010; Jennek et al. 2019).

Besides prior experience, another individual factor that might be crucial for the development of student teachers’ self-efficacy is their professional knowledge. Both, professional knowledge and competence beliefs are described as key components of teachers’ professional competence (Baumert and Kunter 2006). Findings regarding the relation between self-efficacy and pedagogical knowledge of experienced teachers suggested that general, not task-specific, teacher self-efficacy is positively associated with general pedagogical knowledge (Lauermann and König 2016). In regard to student teacher self-efficacy for reflection, results showed that self-efficacy for reflection is positively associated with pedagogical knowledge, which in turn was significantly related to reflective performance (Stender et al. 2021). However, recent research on the relation between self-efficacy and general pedagogical knowledge shows no clear pattern of results as some studies did not find systematic associations for student teachers (König et al. 2012), pre-service teachers (Depaepe and König 2018) or teachers (Lazarides and Schiefele 2021).

5 The present study

Reflection is a central prerequisite for the development of (student) teachers’ professional behaviours. Despite its importance, little is known about the motivational aspects of reflection on teaching. In this study, we therefore examine how self-efficacy for reflection can be enhanced in teacher education. We thereby focus on (i) changes in student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection from the beginning (Time 1) to the end (Time 2) of a semester in the intervention and the control group; (ii) the differences in changes in self-efficacy for reflection between an intervention group that reflected practical experiences versus a control group that did not teach and did not reflect; and (iii) whether the change of self-efficacy for reflection (Time 1 to Time 2) is related to pedagogical knowledge and previous pedagogical experiences of student teachers in the intervention and the control group. More concretely, we investigated the following research questions and hypotheses:

Research question 1

How does student teacher self-efficacy for reflection change across the course of a semester?

Hypothesis 1a

We expect a general increase in student teacher self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers during teacher education.

Hypothesis 1b

Because student teachers’ self-efficacy can be enhanced by mastery experiences as strongest source of self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura 1997; Hußner et al. 2022; Schüle et al. 2017), we assumed that the proposed increase in student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection is stronger for student teachers who gained practical experience in reflecting authentic teaching situations.

Research questions 2

How are prior pedagogical experiences in teaching and pedagogical knowledge related to changes in student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection in context of video-based or protocol-based reflection?

Hypothesis 2a

Prior pedagogical experiences can be a source of mastery experiences (Jennek et al. 2019), but current empirical research showed no significant relation between prior pedagogical experiences in teaching and the change in student teacher self-efficacy (Meschede and Hardy 2020; Oesterhelt et al. 2012)—we therefore tested whether previous pedagogical experiences outside of university practicums were interrelated with changes (Time 1 to Time 2) in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers over one semester who taught and reflected on teaching situations.

Hypothesis 2b

Moreover, research about the relation between teacher self-efficacy and professional knowledge is inconsistent—with some studies indicating positive associations (e.g., Stender et al. 2021) and other studies indicating no systematic relationship (e.g., Lauermann and König 2016)—we therefore tested whether pedagogical knowledge is interrelated with changes (Time 1 to Time 2) in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers over one semester who taught and reflected on teaching situations.

6 Methods

6.1 Sample

In this study we used data from N = 600 student teachers (Intervention group (IG): n = 248; Control group (CG): n = 352) at one German university (52.7% female; 91% born in Germany) who participated in an online questionnaire that assessed student teachers’ motivation and emotion at the beginning (Time 1) and the end (Time 2) of one semester (summer term 2019: n = 61, winter term 2019/2020: n = 51, summer term 2020: n = 127, winter term 2020/2021: n = 111, summer term 2021: n = 87, winter term 2021/2022: n = 162, n = 1 missing information about the semester). Student teachers were on average 24 years old (M = 24.24, SD = 4.78) and in their fifth bachelor semester (M = 4.93, SD = 2.61). The three most-studied subjects of the student teachers were German (19.5%), Sports (13.0%) and English (12.8%). A minority of the student teachers (22.3%) already had previous pedagogical experiences in teaching (M = 10.5 months, SD = 14.88), such as working in schools during their studies. Student teachers in the intervention group (n = 248, missing values for n = 52) reflected on their teaching experience by (a) watching a video of their own teaching practice (n = 98), (b) watching a video of another (student) teachers’ teaching practice (n = 65), or (c) reading a written teaching protocol of one’s own teaching lesson (n = 33).

The students in our sample participated in courses in their teacher education program that focused on the enhancement of student motivation in school. Students in the intervention group participated in courses that provided them with the opportunity to develop lesson plans, to teach lessons based on their lesson plans in authentic classrooms, and to reflect on their lessons based on videos of their own teaching, the teaching of other student teachers, or on a lesson protocol. In a lesson protocol, the student teachers have written down chronologically the observed teaching activities in the classroom. Students in the control group attended courses without such practical experiences and without the associated opportunities for reflection, but with the focus on instructional development through case studies. The intervention is described in further detail in the Design and Procedure section. A total of n = 248 teacher students were in the intervention group (50.5% female, 88.5% born in Germany). These student teachers were on average 24 years old (M = 23.99, SD = 4.63) and were on average in their fifth bachelor semester (M = 5.14, SD = 2.54) when they participated in the survey. The most-studied subjects in the intervention group were German (19.5%), English (13.0%), Ethics (13.0%) and Sports (13.0%). About one third (27.5%) of the students in the intervention group had previous pedagogical experiences (M = 7.98 months, SD = 10.35). Student teachers in the intervention group achieved on average M = 12.82 (SD = 3.59) points out of 23 points in the pedagogical knowledge test. A total of n = 352 student teachers (53.1% female, 93.8% born Germany) were in the control group were on average 24 years old (M = 23.98, SD = 4.42) and were at the time of the survey on average in the fifth semester (M = 4.74, SD = 2.66). The three most-studied subjects in the control group were German (18.5%), History (13.4%) and English (12.8%). About one fifth of the student teachers (19.0%) already had previous pedagogical experiences in teaching (M = 12.61 months, SD = 19.14). Student teachers in the control group achieved on average M = 13.85 (SD = 3.08) points out of 23 points in the pedagogical knowledge test.

6.2 Design and procedure

Our study focusses on student teachers who participated in bachelor courses in educational science that focused on topics of motivating teaching strategies and teaching quality. Student teachers were either in courses that included micro-teaching sessions in secondary classrooms (intervention group) or in courses that were based on cooperative group work without pedagogical practices in schools (control group). Students assigned themselves in one of the courses which are provided in the study plan at the end of the bachelor’s degree in teacher education program. In the intervention group, student teachers were assigned a supervising teacher, developed a teaching concept for one 45–90 min lesson, and taught this lesson in a school. Student teachers prepared this lesson on their own or in teams by transferring the theoretical input of the course that focused on motivational psychology and that was taught during the first weeks of the course into practice. Before teaching, student teachers presented their lessons in the course to receive feedback from the other student teachers in the course and from the lecturer (as possible form of vicarious experience in reflecting). Furthermore, the student teachers sent the lesson plan to the supervising teacher for feedback (as possible form of verbal persuasion in reflecting). To get to know the classroom in which they were going to teach, the student teachers observed one lesson of their supervising teacher in that classroom. Finally, student teachers taught their lesson and videotaped it if it was permitted by the school and if consent was provided by the children and parents. Using the video of their own teaching, a video of another student teacher, or via lesson protocol, student teachers systematically reflected on the lessons by means of a written reflection task (as form of mastery experience in reflecting).

In this task they were requested to select a challenging teaching situation (duration ~5–10 min) on the video and to reflect on this situation using the three-step reflection process which includes 1) the description of the situation, 2) interpretation (evaluation and explanation) of the situation and 3) formulating alternatives for action (Kleinknecht and Gröschner 2016). Once completed, student teachers were requested to select a positive teaching situation (duration ~5–10 min) and to reflect on it. The student teachers in the control group did not teach as part of their course and were not provided with opportunities to systematically reflect. Instead, they worked with classroom video data and engaged in practical tasks such as classroom observation activities or developing solutions to problematic classroom situations which differs in terms of the intensity (e.g., own teaching, written exploration, feedback) compared to the activities in the intervention group.

6.3 Measures

The student teachers were surveyed online at the beginning (Time 1) and the end of the semester (Time 2). The survey assessed student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection, pedagogical knowledge and previous pedagogical experiences in teaching in months. The item wordings from the online survey and the reliabilities (α) for reflection-related self-efficacy, previous pedagogical experience and the pedagogical knowledge are reported in Table 1.

Self-efficacy for reflection at the beginning and the end of one semester was assessed using a scale developed by Fraij (2018)—the German item wording is presented in the Appendix (Tab. A1). The range of the response format is from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Previous pedagogical experiences (as a substitute teacher or assistant teacher) were captured according to König et al. (2013), adding the number of experiences in month.

Pedagogical knowledge was assessed using the 23-item subscale classroom instruction from the original German version of the standardized knowledge test Bilwiss (Kunina-Habenicht et al. 2020). The standardized test includes subdimensions consisting of 23 multiple-choice items, 16 items with a binary response format (“true”/“not true”) and seven items with a four-category response format as a multiple-choice question. The test assesses teachers’ knowledge of different areas of teaching, such as questions on classroom management or cooperative learning. Test scores range from 0 (minimum) to 23 (maximum). The sum of all test items represents the individual knowledge level. In this study, student teachers achieved a minimum of 0.25 to a maximum of 21.25 points.

6.4 Statistical analyses

In a first step, we evaluated measurement invariance of self-efficacy for reflection by using a stepwise procedure described by Byrne (1989) and applied cut-off criteria described by Chen (2007). We tested for strong measurement invariance—this means that we fixed item loadings and intercepts to be invariant across time points. The data met the criteria for time invariance, because a change of ≥ − 0.010 in comparative fit index (∆CFI), ≥ 0.015 in root mean square error of approximation (∆RMSEA), and accompanied with ≥ 0.030 in standardized root mean square residual (∆SRMR) indicate non-invariance (Chen 2007). Measurement invariance of the overall sample was confirmed in our study, the results of the testing procedure are reported in the Appendix (Tab. A2).

To test hypotheses 1a, we applied an unconditional latent change model (LCM) testing the changes in self-efficacy for reflection from the beginning (Time 1) to the end of one semester (Time 2) for all student teachers in the intervention and the control group (McArdle 2009). To examine hypothesis 1b, we used the Wald Chi Square Test (Asparouhouv and Muthén 2007) to examine differences in change scores between the intervention and the control group. To test hypotheses 2a and b, we extended the unconditional LCM and added previous pedagogical experiences in teaching (hypothesis 2a) and pedagogical knowledge (hypothesis 2b) as predictors of the change in self-efficacy for reflection. All analyses were carried out in Mplus version 8.6 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015). In line with Hu and Bentler (1999) the model fit for TLI and CFI, values of 0.90 or higher are considered satisfactory, while values above 0.95 are considered excellent. For the RMSEA, values ≤ 0.05 represent a good fit, values between 0.05 and 0.08 an adequate fit, and values between 0.08 and 0.10 a poor fit (Browne and Cudeck 1993).

7 Results

7.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Mean scores for self-efficacy for reflection, previous pedagogical experiences and pedagogical knowledge for the intervention and the control group are represented in Table 2. The correlations between the captured constructs were examined for student teachers in the intervention (n = 248) and the control group (n = 352).

Correlations are represented in Table 3. There were positive and significant associations between self-efficacy for reflection at the end of a semester (Time 2) and previous pedagogical experiences in teaching (Time 1), but only for student teachers in the intervention group which support that student teachers with high previous pedagogical experiences (Time 1) had high self-efficacy for reflection at the end of one semester (Time 2).

7.2 Latent change analysis

The unconditional latent change model showed that the change in self-efficacy for reflection was positive and significant for the sample as a whole (M∆ = 0.26, p < 0.001). The model fit was good, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06.

To examine the change in self-efficacy for reflection between the intervention and the control group—we used the Wald chi test which showed a significant difference between in group membership with control group being coded as “1” and intervention group coded as “2”, β = 0.18, SE = 0.07, p = 0.011. The model fit was acceptable, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.08.

The unconditional latent change model for student teachers in the intervention group showed a significant change in self-efficacy for reflection from the beginning to the end of a semester, M∆ = 0.23, p < 0.001. The model showed a good model fit, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.18. For student teachers in the control group, the self-efficacy for reflection did not change significantly from the beginning to the end of a semester, M∆ = 0.04, p < 0.305. The model fit was good, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.08.

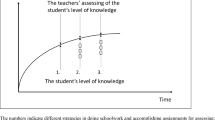

We subsequently computed a conditional latent change model in Fig. 1 in which we included previous pedagogical experiences for teaching and pedagogical knowledge (Time 1) as predictors of the change in self-efficacy for reflection for student teachers in the intervention group from the beginning to the end of one semester (Time 1 to Time 2). The results showed that previous pedagogical experiences for teaching (Time 1) were positively and significantly related to the average change in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers over a semester (Time 1 to Time 2), β = 0.74, p < 0.001. In contrast, pedagogical knowledge (Time 1) of student teachers in the intervention group was negatively but non-significantly associated with the change in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers over one semester (Time 1 to Time 2), β = −0.01, p = 0.985. The model fit for the analysis was acceptable, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.20.

Structural paths for the relations between student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection and the predictors pedagogical knowledge, previous pedagogical experiences and the means of reflection. (The increase in mean value of self-efficacy for reflection in the intervention group was M = 0.23***, the increase in the control group was not significant with M = 0.04)

Moreover, we subsequently computed three conditional latent change models in which we tested if the reflection medium has an impact on the change in student teacher’s self-efficacy for reflection in the intervention group over one semester (Time 1 to Time 2)—no significant effect for the reflection medium on the change of self-efficacy for reflection were foundFootnote 1.

7.3 Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the change in self-efficacy for reflection in a group of student teachers who taught and reflected systematically on their own videotaped teaching experiences, on videotaped experiences of other student teachers or on a lesson protocol (the intervention group) and to compare this to the change in self-efficacy for reflection in a group of student teachers who did not teach and did not reflect (the control group). We also investigated how individual characteristics of student teachers—more concretely, their previous pedagogical experiences in teaching and their pedagogical knowledge—were interrelated with changes in self-efficacy for reflection. In the following sections, we discuss our key findings in detail.

7.4 Motivational aspects of reflection: changes in self-efficacy for reflection

In line with hypothesis 1a, the results of this study showed a positive and significant change in self-efficacy for reflection in student teachers over the course of one semester. Our findings thus support those of recent studies that had shown an increase in student teachers’ self-efficacy over the course of one semester when student teachers were involved in practical phases during teacher education program (Eisfeld et al. 2020; Hußner et al. 2022; Ronfeldt and Reininger 2012). However, other studies found that teacher self-efficacy decreased during practical periods (Lin and Gorrell 2001; Schüle et al. 2017) or did not change significantly for student teachers who could not teach because of the online-semester during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hußner et al. 2022). Reasons for the incoherent findings of the change in teacher self-efficacy might be the different operationalisation and conceptualisations of the examined constructs of teacher self-efficacy beliefs. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that examined changes in student teacher self-efficacy for reflection in context of micro-teaching experiences. Our findings thus contribute to a better understanding of the motivational aspects of reflection processes and their developmental change in teacher education. Whereas theoretical work had described a decline in self-efficacy due to a practical shock (German: Praxisschock) (Richter et al. 2013) or a university shock of student teachers in the first semester (Pfitzner-Eden 2016a), our results indicate that in regard to self-efficacy for reflection, micro-teaching settings and systematic reflections implemented early in teacher education enable student teachers to perceive themselves as competent to reflect own experiences.

In line with Hypothesis 1b, our findings showed that self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers who taught and reflected on teaching experiences systematically increased positively and significantly over one semester during a university course including micro-teaching settings. Self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers who did not teach and who did not reflect did not change significantly over one semester. An explanation for the significant and positive change in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers in the intervention group who taught and reflected on teaching experiences might be that student teachers in the intervention group were asked to develop alternatives for classroom situations that went well for them, but also on experiences that did not go well. These reflective processes might have contributed to an increased perception of own mastery experiences and they may feel encouraged by reflecting on their positive experiences. Against the background of the process of reflective thinking (Dewey 1933) when student teachers were asked to reflect on a challenging teaching situation (of the own video, a video of others or a lesson protocol) it may lead to thinking about state of doubts with regard to classroom behaviour. When student teachers reflected a positive teaching situation, it may lead to minimize the perplexity of the teaching situation, for example because of the perception of positive emotions. An additional analysis showed that student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection at the beginning and the end of one semester is predominantly moderately (Cohen 1988) related to teaching-related self-efficacy (for instructional strategies, rT1 = 0.34, rT2 =0.47; for classroom management, rT1 = 0.30, rT2 =0.44; for student engagement, rT1 = 0.26, rT2 =0.55). Thus, student teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching was associated with their self-efficacy in reflection—however, the moderate correlation coefficients indicate that we assessed different constructs. Each of the self-efficacy facets, however, increased after the reflection of the micro-teaching event (T2) (see Appendix, Tab. A3). Self-efficacy for classroom management increased mostly compared to the other two sub facets of teaching-related self-efficacy or self-efficacy for reflection. However, because we did not assess self-efficacy for reflection right after the micro-teaching event, we cannot be sure whether the increase in self-efficacy for reflection is caused by the teaching experience per se or rather by the structured reflection about the teaching situations, or by the combination of both. Thus, future research should examine in intensive longitudinal designs shorter time-intervals in student teachers’ teaching and reflection processes.

Interestingly, our additional analyses showed no significant differences in changes of self-efficacy for reflection between different means of reflection (videos, protocols). Reasons for these findings might be that the mean of the reflection does not play the main role for the development of self-efficacy for reflection. However, it might be more relevant that the student teachers’ reflection processes are encourage by means of teaching situations (Lazarides and Schiefele 2021).

7.5 Self-efficacy for reflection, prior pedagogical experiences and pedagogical knowledge

Confirming our assumptions (Hypothesis 2a), the change in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers in the intervention group was positively associated with prior teaching experiences which student teachers undertook outside of university in addition to the regular practical phases during their teacher education programs. Our findings are contrary to current findings of empirical research which showed that prior teaching experiences are not significantly associated with self-efficacy beliefs of student teachers (Meschede and Hardy 2020; Oesterhelt et al. 2012). Due to mastery experiences as important source of self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura 1997), prior experiences in teaching might play a relevant role in the context of effective performance in class that student teachers feel more confident in new classroom situations and challenging situations. In this context, student teachers may take the role as a Reflective Practitioner (Schön 1987) by reflecting their own teaching behaviours in class which might lead to the adaption of actions for future teaching situations.

Confirming our assumptions (Hypothesis 2b) and recent research which found no association between professional knowledge and teacher self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., Lauermann and König 2016), the increase in self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers in the intervention group who taught and reflected on teaching situations was not associated with pedagogical knowledge. An explanation might be that for experienced teachers, knowledge is predominantly linked through theoretical knowledge and practical experience referred to the concept reflecting-in-action (Schön 1987), thus knowledge has a stronger impact on self-efficacy for experienced teachers than for student teachers, who acquire theoretical knowledge as part of their studies but are less able to link it to practical experience (Lauermann and König 2016). Another explanation might be that professional knowledge should probably become more significant in the act of reflection (together with self-efficacy) when it comes to determining the quality of reflection, for example by using differentiated knowledge for interpreting and generating alternative courses of action. However, the quality of reflections is not the subject of the current analysis, which is why further studies should examine the links between reflection quality and the change in self-efficacy for reflection in order to gain insight into the structuring of the practice phases in teacher training.

The psychological process that may explain the finding that prior pedagogical experience increases self-efficacy for reflection might be that student teachers with prior experiences in teaching had already had many opportunities to reflect on their teaching behaviours—either because they connected the practical teaching experience with the theory in their studies at the university or through exchange with experienced teachers or other students (Stenberg et al. 2016). Such prior experiences might have enabled them to see teaching experiences in general as an opportunity for reflection—and thus, they might have learned more about themselves and their competences in the domain of reflection during their teaching experience in the semester. In contrast, it might be expected that student teachers with higher professional knowledge can make use of their knowledge to reflect on their teaching experience during the semester. Thus, it can be assumed that professional knowledge alone does not help student teachers feel more competent in the domain of reflection after teaching experiences. Other factors such as feedback from others about explanations they found for their own teaching behaviours or their experience of re-visiting their teaching experience in a systematic reflection process might be more important for feelings of competence in the domain of reflection than knowledge.

7.6 Limitations

Despite its contribution to recent research, our study has various limitations that need to be discussed. First the sample includes student teachers from one German university—therefore it is necessary to evaluate the findings of the positive change of self-efficacy for reflection with samples of student teachers from different universities and with a larger sample to provide greater statistical power. A second limitation is that the content focus of the intervention and the pedagogical knowledge which refers to different areas of teaching and questions about classroom management or cooperative learning of student teachers—whereas the intervention focused on the reflection of micro-teaching experiences in regard of teaching strategies and motivation of students in the class. As a third limitation we consider a missing third group of student teachers who did the practical experiences without systematical reflection on it to identify the impacts of self-efficacy for reflection and practical experience, or the reflection on it. A fourth limitation might be that in our study we did not assess whether the student teachers in both the intervention and the control group gained further practical experience in internships during the examined semester and thus contributed to the positive change in self-efficacy. Moreover, the high perceptions of self-efficacy for reflection at the beginning of one semester for student teachers in both groups might lead to the assumption of the unrealistic optimism about the risk of facing negative events (Weinstein 1989), because student teachers received themselves as self-efficient regarding their reflection ability which represent the fifth limitation of our study.

8 Conclusion

Our study proposes that micro-teaching experiences in teacher education program and systematic reflection of such are useful to enhance self-efficacy for reflection of student teachers. Moreover, the positive effect of previous pedagogical experiences in teaching on the change of student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection indicates that the chance to teach enables student teachers to feel confident for reflecting on challenging situations in the classroom. In future studies, it might be important to examine the knowledge about reflection of student teachers rather than the pedagogical knowledge in general when aiming to examine interrelations between professional knowledge and self-efficacy for reflection. However, it might be interesting if the positive change in self-efficacy for reflection in the context of reflection processes also applies to experienced teachers.

Our findings yield implications for teacher education as micro-teaching experiences and its reflection offer the possibility to reinforce theory and practice transfer as well as the professional development of student teachers.

Notes

Protocol: CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.23;.

Own video: CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.24;.

Videos of other’s: CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.24.

References

Asparouhouv, T., & Muthén, B. (2007). Wald test of mean equality for potential latent class predictors in mixture modeling. http://www.statmodel.com/download/MeanTest1.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2023.

Babaei, M., & Abednia, A. (2016). Reflective teaching and self-efficacy beliefs: exploring relationships in the context of teaching EFL in Iran. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 41(9), 1–26.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2006). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 9(4), 469–520.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In D. K. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park: SAGE.

Bruinsma, M., & Jansen, E. P. (2010). Is the motivation to become a teacher related to pre-service teachers’intentions to remain in the profession? European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 185–200.

Byrne, B. M. (1989). Multigroup comparisons and the assumption of equivalent construct validity across groups: Methodological and substantive issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(4), 503–523.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edn.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cramer, C. (2012). Entwicklung von Professionalität in der Lehrerbildung: Empirische Befunde zu Eingangsbedingungen, Prozessmerkmalen und Ausbildungserfahrungen Lehramtsstudierender. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Depaepe, F., & König, J. (2018). General pedagogical knowledge, self-efficacy and instructional practice: disentangling their relationship in pre-service teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 177–190.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: D.C. Heath & Company.

Eisfeld, M., Raufelder, D., & Hoferichter, F. (2020). Wie sich Lehramtsstudierende in der Entwicklung ihres berufsbezogenen Selbstkonzepts und ihrer Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung in neuen reflexiven Praxisformaten von Studierenden in herkömmlichen Schulpraktika unterscheiden: –Empirische Ergebnisse einer landesweiten Studie in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Herausforderung Lehrer*innenbildung-Zeitschrift zur Konzeption, Gestaltung und Diskussion, 3(1), 48–66.

Fend, H. (1998). Qualität im Bildungswesen. Schulforschung zu Systembedingungen, Schulprofilen und Lehrerleistung. Weinheim: Juventa.

Fraij, A. (2018). Skalendokumentation der Gießener Offensive Lehrerbildung zur Reflexionsbereitschaft. Gießener Elektronische Bibliothek.

Friedman, I. A., & Kass, E. (2002). Teacher self-efficacy: a classroom-organization conceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(6), 675–686.

Gold, B., Hellermann, C., & Holodynski, M. (2017). Effekte videobasierter Trainings zur Förderung der Selbstwirksamkeitsüberzeugungen über Klassenführung im Grundschulunterricht. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 20(1), 115–136.

Gröschner, A., Schindler, A.-K., Holzberger, D., Alles, M., & Seidel, T. (2018). How systematic video reflection in teacher professional development regarding classroom discourse contributes to teacher and student self-efficacy. International Journal of Educational Research, 90, 223–233.

Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Hußner, I., Lazarides, R., & Westphal, A. (2022). COVID-19-bedingte Online-vs. Präsenzlehre: Differentielle Entwicklungsverläufe von Beanspruchung und Selbstwirksamkeit in der Lehrkräftebildung? Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 25(5), 1243–1266.

Jaeger, E. L. (2013). Teacher reflection: supports, barriers, and results. Issues in Teacher Education, 22(1), 89–104.

Jennek, J., Lazarides, R., Panka, K., Körner, D., & Rubach, C. (2019). Funktion und Qualität von Praktika und Praxisbezügen aus Sicht von Lehramtsstudierenden. Herausforderung Lehrer* innenbildung-Zeitschrift zur Konzeption, Gestaltung und Diskussion, 2(1), 39–52.

Karsenti, T., & Collin, S. (2011). The impact of online teaching videos on Canadian pre-service teachers. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 28(3), 195–204.

Kleinknecht, M., & Gröschner, A. (2016). Fostering preservice teachers’ noticing with structured video feedback: Results of an online-and video-based intervention study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.002.

König, J., Kaiser, G., & Felbrich, A. (2012). Spiegelt sich pädagogisches Wissen in den Kompetenzselbsteinschätzungen angehender Lehrkräfte? Zum Zusammenhang von Wissen und Überzeugungen am Ende der Lehrerausbildung. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 58(4), 476–491.

König, J., Rothland, M., Darge, K., Lünnemann, M., & Tachtsoglou, S. (2013). Erfassung und Struktur berufswahlrelevanter Faktoren für die Lehrerausbildung und den Lehrerberuf in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 16(3), 553–577.

Korthagen, F. A. J., Kessels, J., Koster, B., Lagerwerf, B., & Wubbels, T. (2001). Linking practice and theory: The pedagogy of realistic teacher education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kulgemeyer, C., Kempin, M., & Weißbach, A. (2021). Entwicklung von Professionswissen und Reflexionsfähigkeit im Praxissemester. In Naturwissenschaftlicher Unterricht und Lehrerbildung im Umbruch (pp. 262–265).

Kunina-Habenicht, O., Maurer, C., Wolf, K., Holzberger, D., Schmidt, M., Dicke, T., Teuber, Z., Koc-Januchta, M., Lohse-Bossenz, H., & Leutner, D. (2020). Der BilWiss‑2.0‑Test. Diagnostica, 66, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000238.

Lamote, C., & Engels, N. (2010). The development of student teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(1), 3–18.

Lauermann, F., & König, J. (2016). Teachers’ professional competence and wellbeing: understanding the links between general pedagogical knowledge, self-efficacy and burnout. Learning and Instruction, 45, 9–19.

Lazarides, R., & Schiefele, U. (2021). The relative strength of relations between different facets of teacher motivation and core dimensions of teaching quality in mathematics‑a multilevel analysis. Learning and Instruction, 76, 101489.

Lin, H.-L., & Gorrell, J. (2001). Exploratory analysis of pre-service teacher efficacy in Taiwan. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(5), 623–635.

Lohse-Bossenz, H., Schönknecht, L., & Brandtner, M. (2019). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung Reflexionsbezogener Selbstwirksamkeit von Lehrkräften im Vorbereitungsdienst. Empirische Pädagogik, 33(2), 164–179.

Martins, M., Costa, J., & Onofre, M. (2015). Practicum experiences as sources of pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(2), 263–279.

McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 577–605.

Meschede, N., & Hardy, I. (2020). Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen von Lehramtsstudierenden zum adaptiven Unterrichten in heterogenen Lerngruppen. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 23(3), 565–589.

Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., & Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the sources of teaching self-efficacy: a critical review of emerging literature. Educational Psychology Review, 29(4), 795–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9378-y.

Murphy, D. L., & Ermeling, B. A. (2016). Feedback on reflection: comparing rating-scale and forced-choice formats for measuring and facilitating teacher team reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 17(3), 317–333.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Naidoo, K., & Naidoo, L. J. (2021). Designing teaching and reflection experiences to develop candidates’ science teaching self-efficacy. Research in Science & Technological Education, 41(1), 211–231.

Oesterhelt, V., Gröschner, A., Seidel, T., & Sygusch, R. (2012). Pädagogische Vorerfahrungen und Kompetenzeinschätzungen im Kontext eines Praxissemesters-Domänenspezifische Betrachtungen am Beispiel der Sportlehrerbildung. Lehrerbildung auf dem Prüfstand, 5(1), 29–46.

Pfitzner-Eden, F. (2016a). I feel less confident so I quit? Do true changes in teacher self-efficacy predict changes in preservice teachers’ intention to quit their teaching degree? Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 240–254.

Pfitzner-Eden, F. (2016b). Why do I feel more confident? Bandura’s sources predict preservice teachers’ latent changes in teacher self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1486.

Rahm, S., & Lunkenbein, M. (2014). Anbahnung von Reflexivität im Praktikum. Empirische Befunde zur Wirkung von Beobachtungsaufgaben im Grundschulpraktikum. In K.-H. Arnold, A. Gröschner & T. Hascher (Hrsg.), Schulpraktika in der Lehrerbildung: theoretische Grundlagen, Konzeptionen, Prozesse und Effekte (pp. 237–256). Münster: Waxmann.

Richter, D., Kunter, M., Lüdtke, O., Klusmann, U., Anders, Y., & Baumert, J. (2013). How different mentoring approaches affect beginning teachers’ development in the first years of practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 166–177.

Richter, E., Hußner, I., Huang, Y., Richter, D., & Lazarides, R. (2022). Video-based reflection in teacher education: comparing virtual reality and real classroom videos. Computers & Education, 190, 104601.

Ronfeldt, M., & Reininger, M. (2012). More or better student teaching? Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(8), 1091–1106.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schüle, C., Besa, K.-S., Schriek, J., & Arnold, K.-H. (2017). Die Veränderung der Lehrerselbstwirksamkeitsüberzeugung in Schulpraktika. Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung, 7(1), 23–40.

Seidel, T., & Stürmer, K. (2014). Modeling and measuring the structure of professional vision in preservice teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 51(4), 739–771.

Sherin, M. G., & Van Es, E. (2009). Effects of video club participation on teachers’ professional vision. Journal of Teacher Education, 60, 20–37.

Stenberg, K., Rajala, A., & Hilppo, J. (2016). Fostering theory–practice reflection in teaching practicums. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(5), 470–485.

Stender, J., Watson, C., Vogelsang, C., & Schaper, N. (2021). Wie hängen bildungswissenschaftliches Professionswissen, Einstellungen zu Reflexion und die Reflexionsperformanz angehender Lehrpersonen zusammen? Herausforderung Lehrer*innenbildung-Zeitschrift zur Konzeption, Gestaltung und Diskussion, 4(1), 229–248.

Strieker, T., Adams, M., Cone, N., Hubbard, D., & Lim, W. (2016). Supervision matters: collegial, developmental and reflective approaches to supervision of teacher candidates. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1251075.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, W. A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1.

Voss, T., Wagner, W., Klusmann, U., Trautwein, U., & Kunter, M. (2017). Changes in beginning teachers’ classroom management knowledge and emotional exhaustion during the induction phase. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 170–184.

Weinstein, C. S. (1989). Teacher education students‘ preconceptions of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2), 53–60.

Weß, R., Priemer, B., Weusmann, B., Sorge, S., & Neumann, I. (2017). Veränderung von Lehr-bezogenen SWE im MINT-Lehramtsstudium. In C. Maurer (Ed.), Qualitätsvoller Chemie- und Physikunterricht – normative und empirische Dimensionen (pp. 531–534). Gesellschaft für Didaktik der Chemie und Physik, Jahrestagung, Regensburg.

Wyss, C. (2008). Zur Reflexionsfähigkeit und-praxis der Lehrperson. Bildungsforschung. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:4599.

Funding

The study was developed within the programme “Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung” funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Germany (grant number 01JA1516) and the DFG project “Reflexion im pädagogischen Kontext: Interdisziplinäre Systematisierung und Integration” (grant number LO 2635/1-1).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I. Hußner, R. Lazarides, W. Symes, E. Richter and A. Westphal declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hußner, I., Lazarides, R., Symes, W. et al. Reflect on your teaching experience: systematic reflection of teaching behaviour and changes in student teachers’ self-efficacy for reflection. Z Erziehungswiss 26, 1301–1320 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-023-01190-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-023-01190-8