Abstract

This article published in Gruppe Interaktion Organisation (GIO) reports study results on soft skills and mental work ability in young professionals ready to enter the job market. The so-called soft skills (psychological capacities) are nowadays an entrance ticket into the modern working world. Thus, the question is to which degree young professionals who will soon enter the labor market are fit in their soft skills. Are physical or mental health problems related with deficits in soft skills? Which dimensions of soft skills are impaired?

365 young professionals in advanced education from a technical college, who will soon enter the labor market, were investigated via online-questionnaire. Participants were asked to rate their self-perceived capacity level according to Mini-ICF-APP, mental and physical health problems, exam and education-related anxiety, self-efficacy and procrastination.

Students with mental health problems had higher exam anxiety, and lower study-related self-efficacy as compared to students without health problems at all, or students with physical health problems. But, procrastination behavior was similarly present among students with mental health problems and students with physical health problems. Students with health problems did not report globally weaker capacity levels. Lower levels of capacities depend on the type of health problem: In students with mental health problems, social soft skills were impaired rather than content-related capacities. Physical health problems do not affect the self-perceived psychological capacities.

In conclusion, focusing on specific soft skills in training and work adjustment could be fruitful in addition (or as an alternative) to training of profession-specific expertise.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Artikel aus der Zeitschrift Gruppe Interaktion Organisation (GIO) berichtet über Studienergebnisse zur Frage der psychischen (Arbeits)Fähigkeiten bei akademisch qualifizierten Berufseinsteigern mit und ohne (psychischen) Gesundheitsproblemen. Psychische Fähigkeiten, die sogenannten Soft Skills, werden in unserer modernen Arbeitswelt immer wichtiger. Die Frage ist, wie Fähigkeitsprofile bei jungen Berufseinsteigern ausgeprägt sind, ob körperliche oder psychische Erkrankungen mit Defiziten in Fähigkeiten eingehergehen, und welche Fähigkeitsdimensionen ggf. betroffen sind.

365 junge Menschen in fortgeschrittener Ausbildung (Studierende einer technischen Hochschule und einer Fachhochschule), deren Einstieg in den Arbeitsmarkt bevorsteht, nahmen an der Onlineuntersuchung teil. Die Teilnehmenden berichteten im Selbstberichtsfragebogen ihr Fähigkeitsprofil (nach Mini-ICF-APP), examens- oder studiumsbezogene Ängste, Prokratinationsverhalten, und ihre leistungsbezogene Selbstwirksamkeit. Außerdem gaben sie an, ob körperliche oder psychische Gesundheitsprobleme vorliegen.

Studierende mit psychischen Gesundheitsproblemen hatten stärkere Prüfungsängste und geringere Selbstwirksamkeit im Vergleich zu Studierenden mit körperlichen Gesundheitsproblemen oder Gesunden. Prokrastinations-Verhalten war bei Studierenden mit körperlichen oder psychischen Problemen in ähnlicher Größenordnung ausgeprägt.

Studierende mit Gesundheitsproblemen hatten keine generell schwächeren Fähigkeiten. Das Fähigkeitsniveau stand vielmehr in Zusammenhang mit der Art des Gesundheitsproblems: Studierende mit psychischen Gesundheitsproblemen hatten Einschränkungen in sozialen Fähigkeiten, jedoch kaum in Kompetenz- und inhaltsbezogenen Fähigkeiten. Körperliche Gesundheitsprobleme scheinen nicht mit psychischen Fähigkeiten in Zusammenhang zu stehen. In Trainings oder auch bei der Arbeitsplatzanpassung bei Arbeitsbewältigungsproblemen könnte ggf. auf Soft Skills abgezielt werden, alternativ oder ergänzend zum Training inhaltlicher Expertisen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Work requires psychological capacities

Our modern world of work requires a considerable proportion of psychological capacities, tendentially becoming constantly more important. These are for example demands for flexibility, contacts with others and group integration, decision making and judgements, endurance and proactivity (Linden et al. 2010, 2015; Parker and Bindl 2017; West et al. 2009). Young people who will be next to enter the labor market are confronted with these psychological capacity demands, even at the beginning of their professional and academic education (“studies”) period (Goastellec and Ruiz 2015; Schmidt et al. 2019).

Recent studies showed that young people are not only faced with demands for psychological capacities before entering the labor market. A part of them are also already suffering from physical or mental health problems or even both (Pacheco et al. 2017; Wege et al. 2016; Auerbach et al. 2018; Mullins et al. 2017).

Chronic health problems are usually life-long health problems, starting often at a young age (Stansfeld et al. 2008). The problem is that they usually do not make the entry into and success within the labor market easier (Varekamp et al. 2006; Small et al. 2016).

Young professionals affected from health problems are faced with work participation problems and the need to cope with them. Research has shown that observed and self-perceived health-related participation problems are congruent (Linden et al. 2018b).

Build on these facts, the research question arises how young professionals with different health problems perceive their own psychological capacity level, in comparison to healthy students. This will shed light on the type of possible impairments and may give way for specific actions: workplace adjustment or trainings concerning specific capacities.

1.1 Psychological demands in modern working world and professional education

The modern working world requires psychological capacities such as proactivity and crafting a job, fulfilling one or more prescribed roles which may interact, team work capacity, coping with decision latitudes, and others (Parker et al. 2017). Such psychological work demands have been broadly investigated in work psychology research (Parker et al. 2017; Linden et al. 2015).

Professional education takes place in a relatively predefined life context, i.e. younger age, a limited time duration in which a certain goal (finishing education and earning a professional degree) shall be fulfilled. These are concrete goals and reaching them requires certain psycho-mental capacities, i.e. interactional soft skills and cognitive capacities (Goastellec and Ruiz 2015). The latter are general capacities of planning and structuring one’s studies, self-management and proactivity, and—concerning the content of the respective subject or profession—the capacity to apply expertise and to make decisions and judgments.

Occurring problems during professional education can be observed in prolongation of education, i.e. delay in finishing the studies, exam anxiety (potentially especially in higher study years, Manisha et al. 2019), procrastination, and accompanying loss of (work-related) self-efficacy (e.g. Alonso et al. 2018; Middendorff et al. 2017; Naim et al. 2014). There might be structural reasons for problems in education, like the necessity to have a part-time job in parallel to an academic education, or family responsibilities (Porchea et al. 2010).

Analogous to mental work ability demands in all domains of work, also professional and academic education poses mental capacity demands, such as (international) mobility, life-long learning expectation, broad choices of what and where to study, and perceived stress—even if the latter is rather independent from objective work load which has hardly changed over the time (Huisman and van der Wende 2004; Schmidt et al. 2019).

Despite that, there are health-related reasons for problems in education too, i.e. mental or physical illness. In case of widely exceeded duration of education, higher costs for extended educational fees embody an additional burden.

1.2 Mental health problems

According to the modern health definition by the WHO (ICF 2001), health problems should be described with a multidimensional biopsychosocial perspective by considering person factors (socio-demographics, specific characteristics), context factors (e.g. work demands), symptoms (e.g. exam or college anxiety) and activities/capacities (i.e. procrastination behavior, adjustment to rules, flexibility, proactivity) of the person.

Internationally, mental health problems are becoming the greatest health burden. Mental health problems occur in all societal groups, including young professionals and young academics. Mental health problems are associated with psychological capacity disorders, and social participation problems, such as work disability and sick leave (Linden et al. 2010, 2018; Stansfeld et al. 2008). Capacities represent clusters of activities a person can carry out, e.g. adherence to rules, flexibility, proactivity, planning and structuring, group interaction or self care. Capacities rather than symptoms are explanative for work ability (Gatchel et al. 1994; Linden et al. 2010). In social-medicine, the concept of capacities according to the internationally evaluated Mini-ICF-APP (Linden et al. 2009) is routinely used according to guidelines (DRV 2012; SGVP 2012).

Similar to the epidemiology within the general population, the percentage of mental health problems among young professionals and students amounts approximately 30% (Auerbach et al. 2018). Mental health problems are known to be associated with capacity disorders and impairment (Linden et al. 2018), which is found in students as well (Alonso et al. 2018). 25–36% of those who fulfill the criteria of any mental disorder according to DSM‑V report to be in a treatment (Bruffaerts et al. 2019).

The topic mental health in young professionals and students is currently getting more and more attention (Cuijpers et al. 2019; Ebert et al. 2018), including interventions (Harrer et al. 2018). The question is which factors may be associated with impairment—resulting in extended years of education or frequent or long sick leave absence—among some young persons who have mental health problems.

Mental health problems such as loss of motivation, problems with time management, learning deficits, missing contacts to colleagues, fear towards supervisors, problems with self-organization and exam anxieties may occur. Moreover, structural conditions may contribute to prolongation of education. Deficits in exam organization, exams with a high failing rate or studies with admission restriction may contribute to perceived problems. The study subject does not play an important role in prolonged education (Terbuyken 2005). Support and coaching by the educational institution may reduce problematic prolongation of education.

Person-related aspects which may be problematic and thus might contribute to prolongation of education duration are perceived low self-efficacy, high exam anxiety (Naim et al. 2014), high procrastination and perceived deficits in psycho-mental capacities, such as interactional soft skills, work and organizational capacities and expertise-related capacities.

Another aspect which could be associated with absence and problems in education is college phobic anxiety. This phenomenon has been described early (Hodgman and Braiman 1965) and means, similar to workplace phobic anxiety (Muschalla and Linden 2009), that the affected person suffers from intense fear when thinking about or coming near the education/college place, resulting in an avoidance behavior, which may present itself as increased absence durations. College phobic anxiety is thus more general than exam anxiety. Exam anxiety affects specifically examination situations and does not mean general avoidance behavior towards the educational institution.

1.3 Question of research

Why is it important to study mental health in young professionals who are presently in the last phase of their education? Young persons are the future working persons who built the stability of societies. The working world is changing with increased demands for coping with mental demands at work (instead of physical demands) (von Ameln and Wimmer 2016). Thus, it is important to know about the empirical reality of mental capacity levels, and possible determinants and accompanying factors of mental capacity (and in some cases even capacity impairment) in the group of presumably “fit” persons of their cohorts.

Since the modern working world requires psychological capacities respective soft skills (Linden et al. 2018; von Ameln and Wimmer 2016), but nothing is presently known about the capacity profiles of young professionals right before entrance into working life, it is of interest which capacity dimensions may be endangered to be vulnerable or in some persons even impaired. Then, interventions may address the concrete capacity dimensions of interest—be it for person trainings, or adjustment of education programs and work tasks.

The explorative questions of research are therefore:

-

1.

Are there differences in personal factors (age, sick leave duration, college-related anxiety, procrastination behavior, study-related self-efficacy, exam anxiety) in young professionals without health problems, young professionals with physical health problems and young professionals with mental health problems?

-

2.

Are there differences in the subjective perception of their psychological capacities in young professionals without health problems, young professionals with physical health problems, and young professionals with mental health problems?

-

3.

Are there differences in the subjective perception of their psychological capacities in young professionals (with mental health problems) in comparison to mid-aged persons (with mental health problems)?

-

4.

(To which degree) are weak psychological capacity levels associated with mental or physical health problems?

2 Method

An online questionnaire was distributed in different colleges. In order to gather a heterogeneous sample, all subjects and types of colleges (state and private, scientific and practice-oriented colleges) were included. Participants filled in their socio-demographics, including study-related aspects: number of semesters studied until now, high-school leaving degree, absence duration from their educational setting within the past 12 months. Additionally, the students were asked whether they suffered from a physical or a mental health problem, or both.

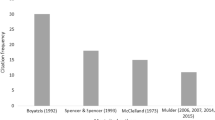

Psychometric scales were then given, including the exam anxiety scale (Hodapp et al. 2011), the Procrastination Scale (GPS‑K, Klingsiek and Fries 2018), the scale for self-efficacy in studies (adapted from Schyns and Collani 2002), the college phobia scale (adapted from the workplace phobia scale WPS, Muschalla and Linden 2009), and the psycho-mental capacities self-rating Mini-ICF-APP‑S (Linden et al. 2018).

553 young professionals opened the questionnaire, and 365 finished and could be included into analysis with full data. 238 had no health problems, 47 had physical health problems, 40 had mental health problems, and 40 had physical and mental health problems.

2.1 Participants

Young professionals were on average 23.11 years old (SD = 3.7), 67.9% were female, 92.5% were in education at a state college, 7.5% at a private college. Students had a high school leaving degree of on average 2.19 (SD = 0.77), were presently studying for averaging 6.5 (SD = 4.45) semesters in total and 4 (SD = 2.9) semesters in their current professional field. They have been on sick leave for averagely 1.75 (SD = 4.54) weeks within the past 12 months, 35% said that they have any health problem and 75% among these said that the health problem impaired their studies. Most (85%) of the students had hobbies, 24.1% lived with a partner, 39.8% lived in shared apartment or in dormitories, 17.3% in their parents’ home, 18.9% on their own. 3% had already children. Most of the students (74.9%) got financial support for studies from their parents, 48.7% had an additional job parallel to education, 22.5% obtained financial support from the state (Bafög).

The investigated young professionals in this study are in most aspects similar to a national representative German student sample (N = 67,007; Middendorff et al. 2017): Students from that national sample were on average 24.7 years old, 48% had a partnership, 6% had children, 11% reported health problems which impair their studies (47% of these due to mental health problems). Concerning financial study support, 86% reported support by their parents, 61% had a job parallel to studies, 25% perceived state financial support. A difference is that within the here investigated students there were more females than in the national sample (48%).

2.2 Instruments

Item examples, rating formats and number of items of the self-rating scales used in this study are displayed in Table 1.

Mini-ICF-APP-S

An instrument to quantify psychological capacities, or soft skills, is the Mini-ICF-APP (Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation disorders in mental illness, Linden et al. 2009, 2015; Balestrieri et al. 2013; Molodynski et al. 2013). It has become a standard in guidelines for socio-medical expert assessments (DRV 2012; SGVP 2012). The Mini-ICF-APP capacity concept has proven validity in the sense of correlations with the ability to work and the dimensions of the Groningen Social Disability Schedule (Wiersma et al. 1990). It posesses sensitivity to change (Linden et al. 2015). There are 13 capacity dimensions (Table 1). In the Mini-ICF-APP‑S, participants are asked to give a rating how well they are in the 13 capacities. Detailed descriptions of the dimensions are given and the ratings are described on a behavioral level. The bipolar rating prevents a bias towards aggravation of incapacity in clinical samples. The Mini-ICF-APP‑S has been successfully evaluated in a large survey with clinical (n = 1143) and general population (n = 102) samples (Linden et al. 2018).

College phobia scale

The College Phobia Scale, CPS, measures college-related anxiety. It is an adapted version of the evaluated Workplace Phobia Scale (WPS, Muschalla and Linden 2009), which measures panic and avoidance behaviour towards the workplace. For the presently used college phobia version, each item of the WPS has been adjusted to read “at college” instead of “at work”. The college phobia scale is given to the participants under the title ‘questionnaire on college problems’ which examines ‘behaviour, thoughts, and feelings which can occur in relation to college’. In different working samples, about 4–5% of general population report high work phobic anxiety (Vignoli et al. 2017; Muschalla et al. 2013). A mean score from the college phobia scale reflects the overall college phobic anxiety.

Exam anxiety

The exam anxiety scale (Hodapp et al. 2011) is self-rating for thoughts and feelings in exam situations. Exam anxiety has been operationalized as situation-specific characteristic which includes the dimensions tenseness, worrying, interference and defect in optimism. The person is asked to say to which degree s/he normally feels anxiety in situations of examination.

General procrastination scale

The Procrastination Scale (GPS‑K, Klingsiek and Fries 2018) describes dysfunctional postponement of duties in spite of knowing it should be done now.

Self-efficacy in education

The adapted scale for occupational self-efficacy (Schyns and Collani 2002) measures how strongly a person is convinced to conduct a certain behavior within the education and studying context.

Chronic health problems

Participants were asked: “Do you suffer from health problems?” If they stated “yes”, they were asked: “Are your health problems chronic?” and which type: “mental disorder”, or “physical disorder”. If a participant had both, s/he marked both mental and physical disorder in the questionnaire.

Similarly, in studies in outpatient service, such self-reports of chronic (mental) health issues have been assessed (Muschalla and Linden 2014; Linden et al. 2018b) and regularly turn out to be valid in comparison with structured diagnostic interviews or observer-ratings.

3 Results

3.1 Education-related problems and personal characteristics

Young professionals with mental health problems have higher exam anxiety (Table 2), and lower study-related self-efficacy as compared to those without health problems at all, or those with physical health problems.

However, procrastination behavior is similarly present in young professionals with mental health problems and young professionals with physical health problems. Furthermore, sick leave is similar in young professionals with mental or physical health problems, but those who suffer from both are significantly longer on sick leave than all others.

There are no differences in age, high school leaving degree or number of study duration. In the groups of young professionals with any kind of health problem, women are over-represented.

3.2 Psychological capacities

Young professionals with mental health problems perceive a part of their capacities (Table 3) lower than do young professionals with physical or without health problems: Those with mental health problems reported lower capacity levels in flexibility, proactivity, endurance, self-care. Similarly, they perceived partly lower capacity level in social capacity dimensions i.e. contacts with thirds, group capacity, assertiveness.

One capacity which turned out to be a slight problem among young professionals with health problems (in a mental as well as in a physical manner) was mobility: They rated their mobility capacity lower than young professionals without any health problem.

Adjustment to rules and routines, decision making and judgment together with applying expertise were similar in all groups, indicating no significant difference between young professionals with or without any type of health problems.

In comparison to the capacity levels of older persons with mental health problems (average age 50 years, Linden et al. 2018), young professionals with mental health problems show similar results in their capacity self-rating (Table 3). The only exceptions are that young professionals with mental health problems judge themselves better in decision making and mobility, but worse in endurance and making contacts.

Interestingly, healthy students perceive their capacities partly lower than older persons from the general population, namely in flexibility, competency, proactivity and contacts.

3.3 Capacities and health problems

Capacities are independent from age, sex, high school leaving grade and physical health problems (Table 4). In contrast, lower perceived mental capacities are rather consistently associated with mental health problems and specific behavioral problems like college anxiety, exam anxiety, procrastination behavior, low study-related self-efficacy.

4 Discussion

On the one hand, data show that some capacity dimensions are associated with mental health problems, but not with physical health problems. These were the so-called soft skills which require psychological functions such as interactional capacities (contact, group, assertiveness), planning and structuring, proactivity, flexibility. These capacities are not bound to specific contents, in contrast to capacities which rather refer to specific knowledge or content issues. This finding is similar to what is known from middle-aged persons: those with mental health problems report lower capacity levels than mentally healthy persons (Linden et al. 2018a).

On the other hand, some capacities are perceived similarly among students with and students without health problems. These are the capacities which reflect more content-associated issues: applying expertise, decision making. Applied to the field of profession-oriented education, as has been done here, these capacities reflect professional capacities. In such “content-directed” capacities young professionals with and without health problems are equally fit, because this is a relevant entrance capacity to professional education.

Students with physical health problems report similar psychological capacity levels like healthy students. A physical health problem may be associated with a higher need for the person to adjust to difficult context conditions, applying for assistance or inventing new ways of active coping (Dempster et al. 2015; Reynolds et al. 2016), adjusting to or tolerating conditions, and using self-help means (Lambert et al. 2017). Students with physical health problems thus may be faced with rather higher demands for flexibility, group integration and tolerance of context conditions. It may be that they are well trained in these capacities and therefore do not perceive restrictions in comparison to completely healthy persons.

Psychosomatic patients (Linden et al. 2018), as well as students with mental health problems report partly similar profiles of their capacities: They see capacity problems in assertiveness, proactivity, endurance and flexibility, rather than in adherence to regulations, or decision making or competency. Mental health problems are regularly chronic in their nature (Stansfeld et al. 2008) and thus may appear with similar capacity problems in different age groups, and over the life span. Longitudinal studies on psychological capacities are needed, but the here reported data suggest at least that the most often perceived problems in different age groups seem to be interactional problems (assertiveness), activity-related problems (endurance, proactivity), and flexibility.

The fact that healthy students judge their capacities partly lower than do older persons from the general population is congruent to findings in a large psychosomatic patient sample. Furthermore, it was found that older patients perceive their psychological capacities as better than younger patients (Linden et al. 2018). Similar findings are also discussed for other capacities, for example wisdom, which seems to be higher in the middle years of life than in the early years (Ardelt and Oh 2016).

4.1 Limitations

In this here investigated sample women were overrepresented. However, since the research interest here was the comparison of mental healthy and mental ill persons, and the percentage of females is higher in the mental ill group (similar to epidemiology studies on mental disorders), this signals that the sample is valid concerning the typical gender distribution of mental health problems (Linden et al. 2018).

Data was collected through a cross-sectional self-report investigation and reflect therefore the young professionals’ perception of their psychological capacities at one time. There might be an overestimation of possible correlations due to a common response pattern (common method bias). Furthermore, results might be influenced by the different sizes of the four groups.

However, since observable performance problems and problems in work ability are to a high degree predicted by self-perceived work ability or performance expectation (de Vries et al. 2018), these self-reports are of great importance. They build the basis for the identification of persons at risk, and what to address to whom as preventive actions.

5 Conclusion and outlook

The obtained data from this present investigation support the idea that preventive action for young professionals at risk—similar to mid-life employees at risk—may focus on supporting interactional, self-management and soft skills (McEwan et al. 2017; Oakman et al. 2018; Carolan et al. 2017). This is even more important as nowadays team work and other interactional and management capacities are required in almost all professional fields (Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2011; McEwan et al. 2017; BAuA 2019).

Capacity trainings and optimization of resources can be offered by companies within occupational health programs. These can be fruitful for job beginners as well as other employees. There is a broad variety of evaluated behavior-oriented trainings which can be conducted in single or group settings (Linden et al. 2015). In each single case, specific interventions for the specific capacities of interest must be chosen (instead of delivering one standard training to everybody). According to the person-job/role-fit-model (French 1973), the specific job situation and job demands and the capacity profile of the trainee must be considered: a shy sales employee might need training of contact and interactional capacities, a person newly promoted into a leading position might be trained in team (leading) capacity and decision making, whereas a technician might rather need specific competence skills. Employers must also be aware of the fact that not everybody can be trained to become a champion. People have different capacity profiles and different limitations in trainability. Finding the right person-job-fit, i.e. the right person for specific tasks, is another way of successful coping with mental work demands. (Young) employees self-reports of their capacity profiles can be used as a starting point for finding the right person-job-fit.

References

Alonso, J., Vilagut, G., Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Bruffaerts, R., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Ennis, E., Gutiérrez-Garcia, R. A., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Lee, S., Bantjes, J., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., Kessler, R. C., & WMH-ICS Collaborators, W. H. O. (2018). The role impairment associated with mental disorder risk profiles in the WHO World Mental Health International College Student Initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28, e1750. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1750.

von Ameln, F., & Wimmer, R. (2016). Neue Arbeitswelt, Führung und organisationaler Wandel. Gruppe Interaktion Organisation, 47, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-016-0303-0.

Ardelt, M., & Oh, H. (2016). Correlates of wisdom. In S. K. Whitbourne (Ed.), The ececlopedia of adulthood and ageing (pp. 262–264). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118528921.wbeaa184.

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., Kessler, R. C., & WMH-ICS Collaborators, W. H. O. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127, 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362.

Balestrieri, M., Isola, M., Bonn, R., Tam, T., Vio, M., Linden, M., & Maso, E. (2013). Validation of an Italian version of the Mini-ICF-APP, a short instrument for rating activity and participation restrictions in psychiatric disorders. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 22, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796012000480.

BAuA (2019). Grundauswertung der BIBB/BAuA Erwerbstätigenbefragung 2018. https://www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/Publikationen/Berichte/F2417-2.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3. Accessed 6 Feb 2020.

Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Hermosillo De la Torre, A. E., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Stein, D. J., Ennis, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., Kessler, R. C., & WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators (2019). Lifetime and 12-months treatment for mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among first year college students. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20, e1764. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1764.

Carolan, S., Harris, P. R., & Cavanagh, K. (2017). Improving employee wellbeing and effectiveness: systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the Workplace. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, e271. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7583.

Cuijpers, P., Auerbach, R. P., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., Ebert, D., Karyotaki, E., & Kessler, R. C. (2019). Introduction to the special issue: The WHO World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 9, e1762. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1762.

Dempster, M., Howell, D., & McCorry, N. K. (2015). Illness perceptions and coping in physical health conditions: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 79, 506–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.10.006.

DRV (2012). Leitlinien für die sozialmedizinische Begutachtung. Sozialmedizinische Beurteilung bei psychischen und Verhaltensstörungen. https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Experten/infos_fuer_aerzte/begutachtung/empfehlung_psychische_stoerungen_2006_pdf.pdf;jsessionid=B1D7D700851F4403D5818618290207EB.delivery1-9-replication?__blob=publicationFile&v=1. Accessed 6 Feb 2020.

Ebert, D. D., Franke, M., Kählke, F., Küchler, A. M., Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Alonso, J., Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Auerbach, R. P., Kessler, R. C., Baumeister, H., WHO World Mental health – International College Student collaborators (2018). Increasing intentions to use mental health services among university students. Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial within the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health International College Student Initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20, e1754. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1754.

French Jr., J. R. P. (1973). Person role fit. Occupational Mental Health, 3, 15–20.

Gatchel, R. J., Polatin, P. B., Mayer, T. G., & Garcy, P. D. (1994). Psychopathology and the rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 75, 666–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9993(94)90191-0.

Goastellec, G., & Ruiz, G. (2015). Finding an Apprenticeship: hidden curriculum and social consequences. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01441.

Harrer, M., Adam, S. H., Baumeister, H., Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Auerbach, R. P., Kessler, R. C., Bruffaerts, R., Berling, M., & Ebert, D. D. (2018). Internet interventions for mental health in university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26, e1759. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1759.

Hodapp, V., Rohrmann, S., & Ringeisen, T. (2011). PAF-Prüfungsangstfragebogen. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Hodgman, C. H., & Braiman, A. (1965). “College phobia”: school refusal in university students. American Journal of Psychiatry, 121, 801–805. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.121.8.801.

Huisman, J., & van der Wende, M. (2004). On cooperation and competition. National and European Policies on Internationalisation of Higher Education. Bonn: Lemmens.

Kauffeld, S., & Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2011). Meetings matter: effects of team meetings on team and organizational success. Small Group Research, 43, 130–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496411429599.

Klingsiek, K. B., & Fries, S. (2018). Allgemeine Prokrastination. Entwicklung und Validierung einer deutschsprachigen Kurzskala der General Procrastination Scale. Diagnostica, 58, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000060.

Lambert, S. D., Beatty, L., McElduff, P., Levesque, J. V., Lawsin, C., Jacobsen, P., Turner, J., & Girgis, A. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of written self-administered psychosocial interventions among adults with a physical illness. Patient Education and Counselling, 199, 2200–2217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.039.

Linden, M., Baron, S., & Muschalla, B. (2009). Mini-ICF-Rating für psychische Störungen (Mini-ICF-APP). Ein Kurzinstrument zur Beurteilung von Fähigkeits- bzw. Kapazitätsstörungen bei psychischen Störungen. Göttingen: Hans Huber.

Linden, M., Baron, S., & Muschalla, B. (2010). Capacity according to ICF in relation to work related attitudes and performance in psychosomatic patients. Psychopathology, 43, 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1159/000315125.

Linden, M., Baron, S., & Muschalla, B. (2015). Mini-ICF-Rating für Aktivitäts- und Partizipationsbeeinträchtigungen bei psychischen Erkrankungen (Mini-ICF-APP). Ein Kurzinstrument zur Fremdbeurteilung von Aktivitäts- und Partizipationsbeeinträchtigungen bei psychischen Erkrankungen in Anlehnung an die Internationale Klassifikation der Funktionsfähigkeit, Behinderung und Gesundheit (ICF) der Weltgesundheitsorganisation. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber.

Linden, M., Keller, L., Noack, N., & Muschalla, B. (2018a). Self-rating of capacity limitations in mental disorders: The “Mini-ICF-APP-S”. Behavioral Medicine and Rehabilitation Practice, 101, 14–21.

Linden, M., Deck, R., & Muschalla, B. (2018b). Rate and spectrum of participation impairment in patients with chronic mental disorders: comparison of self- and expert ratings. Contemporary Behavioral Health Care, 3, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.15761/CBHC.1000124.

Manisha, M., Pavithra, V., & Suganya, M. (2019). Evaluation of exam anxiety among health science students. International Journal of Research and Review, 6, 359–363. https://doi.org/10.4444/ijrr.1002/1389.

McEwan, D., Ruissen, G. R., Eys, M. A., Zumbo, B. D., & Beauchamp, M. R. (2017). The effectiveness of teamwork training on teamwork behaviors and team performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventions. PLoS ONE, 12, e169604. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169604.

Middendorff, E., Apolinarski, B., Becker, K., Bornkessel, P., Brandt, T., Heißenberg, S., & Poskowsky, J. (2017). Die wirtschaftliche und soziale Lage der Studierenden in Deutschland 2016. 21. Sozialerhebung des Deutschen Studentenwerks – durchgeführt vom Deutschen Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung. Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). https://www.studentenwerk-oberfranken.de/fileadmin/content/default/_downloads/se21_hauptbericht.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2020.

Molodynski, A., Linden, M., Juckel, G., Yeeles, K., Anderson, C., Vazquez-Montes, M., & Burns, T. (2013). The reliability, validity, and applicability of an English language version of the Mini-ICF-APP. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 1347–1354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0604-8.

Mullins, A. J., Gamwell, K. L., Sharkey, C. M., Bakula, D. M., Tackett, A. P., Suorsa, K. I., Chaney, J. M., & Mullins, L. L. (2017). Illness uncertainty and illness intrusiveness as predictors of depressive and anxious symptomology in college students with chronic illnesses. Journal of American College Health, 65, 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2017.1312415.

Muschalla, B., & Linden, M. (2009). Workplace Phobia—a first explorative study on its relation to established anxiety disorders, sick leave, and work-directed treatment. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 14, 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500903207398.

Muschalla, B., & Linden, M. (2014). Workplace phobia, workplace problems, and work ability in primary care patients with chronic mental disorders. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 27, 486–494. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.04.130308.

Muschalla, B., Heldmann, M., & Fay, D. (2013). The significance of job-anxiety in a working population. Occupational Medicine, 63, 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqt072.

Naim, H., Khan, W. A., Naim, H. H., & Jawaid, M. (2014). Examination related anxiety and its management amongst medical students. Journal for Studies in Management and Planning, 1, 104–114.

Oakman, J., Neupane, S., Proper, K. I., Kinsman, N., & Nygard, C. H. (2018). Workplace interventions to improve work ability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of their effectiveness. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health, 44, 134–146. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3685.

Pacheco, J. P., Giacomin, H. T., Tam, W. W., Ribeiro, T. B., Arab, C., Bezerra, I. M., & Pinasco, G. C. (2017). Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 39, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223.

Parker, S. K., & Bindl, U. K. (2017). Proactivity at work: making things happen in organizations. London: Routledge.

Parker, S. K., Morgeson, F. P., & Johns, G. (2017). One hundred years of work design research: looking back and looking forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102, 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000106.

Porchea, S. F., Allen, J., Robbins, S., & Phelps, R. P. (2010). Predictors of long-term enrollment and degree outcomes for community college students: integrating academic, psychosocial, socio-demographic, and situational factors. The Journal of Higher Education, 81, 680–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2010.11779077.

Reynolds, N., Mrug, S., Wolfe, K., Schwebel, D., & Wallander, J. (2016). Spiritual coping, psychosocial adjustment, and physical health in youth with chronic illness: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychology Review, 10, 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1159142.

Schmidt, L., Scheiter, F., Neubauer, A. B., & Sieverding, M. (2019). Anforderungen, Entscheidungsfreiräume und Stress im Studium. Erste Befunde zu Reliabilität und Validität eines Fragebogens zu strukturellen Belastungen und Ressourcen (StrukStud) in Anlehnung an den Job Content Questionnaire. Diagnostica, 65, 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000213.

Schyns, B., & Collani, G. (2002). A new occupational self-efficacy scale and its relation to personality constructs and organizational variables. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11, 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320244000148.

SGVP (2012). Qualitätsleitlinien für psychiatrische Gutachten in der Eidgenössischen Invalidenversicherung. https://www.swiss-insurance-medicine.ch/tl_files/firstTheme/PDF%20Dateien%20ab%202015/4%20Fachwissen%20nachschlagen/Medizinische%20Gutachten/SIM%20Qualitaetsleitlinien%20IV%20Gutachten.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2020.

Small, S., de Boer, C., & Swab, M. (2016). Perceived barriers to and facilitators of labor market engagement for individuals with chronic physical illness in their experiences with disability policy: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 13, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2493.

Stansfeld, S. A., Clark, C., Caldwell, T., Rodgers, B., & Power, C. (2008). Psychosocial work characteristics and anxiety and depressive disorders in midlife: the effects of prior psychological distress. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2007.036640.

Terbuyken, G. (2005). Der Langzeitstudent – das unbekannte Wesen? Daten zu Langzeitstudierenden des Studiengangs Sozialwesen an der Evangelischen Fachhochschule Hannover. Hannover: Blumhardt-Verlag.

Varekamp, I., Verbeek, J. H., & van Dijk, F. J. (Hrsg.) (2006). How can we help employees with chronic diseases to stay at work? A review of interventions aimed at job retention and based on an empowerment perspective. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 80, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-006-0112-9.

Vignoli, M., Muschalla, B., & Mariani, M. G. (2017). Workplace phobic anxiety as a mental health phenomenon in the job demands-resources model. BioMed Research International, 2017, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3285092.

de Vries, H., Fishta, A., Weikert, B., Rodriguez Sanchez, A., & Wegewitz. U. (2018). Determinants of Sickness Absence and Return to Work Among Employees with Common Mental Disorders: A Scoping Review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 28, 393-417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9730-1.

Wege, N., Muth, T., & Angerer, P. (2016). Mental health among currently enrolled medical students in Germany. Public Health, 132, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.12.014.

West, B. J., Patera, J. L., & Carsten, M. K. (2009). Team level positivity: investigating positive psychological capacities and team level outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.593.

WHO (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wiersma, D., DeJong, A., Kraaijkamp, H. J. M., & Ormel, J. (1990). The Groningen social disabilities schedule. Manual and questionnaires, 2nd version. World Health Organization: University of Groningen, Department of Social Psychiatry.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muschalla, B., Kutzner, I. Mental work ability: young professionals with mental health problems perceive lower levels of soft skills. Gr Interakt Org 52, 91–104 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-021-00552-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-021-00552-2