Abstract

Background

Advocacy is an integral component of a physician’s professional responsibilities, yet efforts to teach advocacy skills in a systematic and comprehensive manner have been inconsistent and challenging. There is currently no consensus on the tools and content that should be included in advocacy curricula for graduate medical trainees.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review of recently published GME advocacy curricula and delineate foundational concepts and topics in advocacy education that are pertinent to trainees across specialties and career paths.

Methods

We conducted an updated systematic review based off Howell et al. (J Gen Intern Med 34(11):2592–2601, 2019) to identify articles published between September 2017 and March 2022 that described GME advocacy curricula developed in the USA and Canada. Searches of grey literature were used to find citations potentially missed by the search strategy. Articles were independently reviewed by two authors to identify those meeting our inclusion and exclusion criteria; a third author resolved discrepancies. Three reviewers used a web-based interface to extract curricular details from the final selection of articles. Two reviewers conducted a detailed analysis of recurring themes in curricular design and implementation.

Results

Of 867 articles reviewed, 26 articles, describing 31 unique curricula, met inclusion and exclusion criteria. The majority (84%) represented Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, Pediatrics, and Psychiatry programs. The most common learning methods included experiential learning, didactics, and project-based work. Most covered community partnerships (58%) and legislative advocacy (58%) as advocacy tools and social determinants of health (58%) as an educational topic. Evaluation results were inconsistently reported. Analysis of recurring themes showed that advocacy curricula benefit from an overarching culture supportive of advocacy education and should ideally be learner-centric, educator-friendly, and action-oriented.

Discussion

Combining core features of advocacy curricula identified in prior publications with our findings, we propose an integrative framework to guide design and implementation of advocacy curricula for GME trainees. Additional research is needed to build expert consensus and ultimately develop model curricula for disseminated use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Advocacy is a key component of the modern physician’s professional responsibilities according to many influential medical organizations, including the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)1], American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)2, American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM)3, American College of Physicians (ACP)3, American Medical Association (AMA)4, 5, American Psychiatric Association (APA)6, and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada7–22. ACGME common program requirements for residents and fellows across specialties acknowledge education on social determinants of health (SDOH) and health disparities16,23, 24 as essential; advocacy education is included but in a very limited scope as it pertains to direct patient care and patient care systems.25 The CanMEDS framework used in Canada more explicitly identifies health advocate as one of seven core abilities physicians must demonstrate to expertly care for patients15,22.

Graduate medical trainees across specialties13, 14,21 have demonstrated interest in learning about advocacy and developing practical advocacy skills.13 As the last intensive didactic opportunity prior to independent medical practice, the graduate medical education (GME) years present a prime opportunity to teach advocacy. Data suggests that meaningful engagement in advocacy can reinforce physician identity and the choice to practice medicine8–11,26, provide an outlet for stress management27, mitigate burnout7–9,26,28, and support professional development29. Despite increasing recognition of its importance, advocacy education remains elusive and challenging. Residents and fellows face significant time constraints due to extensive direct patient care responsibilities, and some trainees may even consider advocacy-related activities to be burdensome or unrealistic given competing demands21. Advocacy is also difficult to teach and assess30. Lack of formal7, 8,11,19,21, explicit9,31, and consistent11,16,32 training leads to inadequate preparation13,28,33 of trainees and negatively impacts patient care13. Perhaps most challenging for educators in this space has been the lack of formal curricula and guidelines to facilitate teaching efforts15–17,19.

In 2019, Howell et al. published the first systematic review analyzing methodologies, structure, content, facilitating factors, and barriers across GME advocacy curricula34. They analyzed 38 articles published through September 2017 and found that the most common tools covered in advocacy curricula included health policy and legislative advocacy, persuasive communication (media advocacy, op-ed writing, public speaking), grassroots advocacy, community partnership, and research-based advocacy. They concluded that advocacy education can “benefit from continued development of standardized goals, content, and outcome measures to better correlate with stated educational objectives.”.34

Since this initial review 5 years ago, a spotlight on structural inequities and resultant health disparities, laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic, has pushed physician advocacy to the forefront of national conversation35–37, and many programs have published their GME advocacy curricula, sharing creative solutions to barriers as well as lessons learned in curricular implementation. Given the substantial effort and expertise required to develop curricula de novo, several authors have called for developing and disseminating advocacy curricula that can be adapted across GME programs and specialties16,21. We hypothesized that this new wave of articles represents a critical mass sufficient for investigating any significant changes in advocacy education in the last 5 years and analyzing common themes and program structures that could serve as a basis for an eventual model curriculum. For these reasons, we conducted an updated systematic review utilizing a search strategy similar to that created by Howell et al. to evaluate GME advocacy curricula published from September 2017 to March 2022. Building on the foundational concepts presented in the Howell review, our work aimed to delineate a comprehensive landscape of GME advocacy curricula and provide new insights into the common components (e.g., logistics, tools, content, evaluation methods), key barriers, and best practices that can guide development of model advocacy curricula for disseminated use across GME programs and specialties.

METHODS

A medical librarian (RO) conducted systematic literature searches in PubMed (NLM), Embase (Embase.com), PsycINFO (ProQuest), and Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC via ProQuest) databases (Appendix). Search strategies for PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO were replicated using those published in the prior study34. The original documentation did not reveal a replicable ERIC strategy, so a new strategy was designed, mapping closely to the original intent of the PsycINFO database strategy. Citations were included from September 1, 2017, to March 4, 2022. One author (AA) searched MedEdPORTAL (see the Appendix for search strategy) to identify additional curricular content published September 2017 forward. As in the prior study, search concepts included graduate medical education, curriculum, advocacy, community engagement, human rights, social justice, lobbying, vulnerable populations, and poverty. Deduplication algorithms in EndNote™38 were run against all citations.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined using the prior study’s criteria as a guide: English language manuscripts published between September 1, 2017 and March 4, 2022, describing graduate medical educational curricula in US and Canadian programs and explicitly discussing concepts related to advocacy training. Articles were excluded if the topic had narrow educational scope (i.e., limited to only clinic-based quality improvement and population health, only individual patient advocacy, or describing a single community resource), described programs outside the USA and Canada, published as an abstract only, or published in a language other than English. Similar to the prior study, we used the Earnest et al. definition of advocacy: “action by a physician to promote social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being.”.5

Two reviewers (AA, JL) independently screened titles and abstracts of all citations identified in the initial search for inclusion and exclusion with disputes resolved by a third reviewer (NA). Two reviewers (JL, NA) then hand searched the bibliographies of included articles for potential articles not previously identified. One reviewer (NA) also reviewed all articles citing the original Howell study, which revealed additional articles from Web of Science and PubMed. Duplicate articles were identified and removed. One reviewer (NA) read the abstracts for all articles identified via these additional search methods. No automation tools, other than EndNote™, were used during any step of the search process, and the strategy was not registered with PROSPERO since it was derived directly from the prior study.

All three reviewers (AA, JL, NA) read the final set of selected articles; each reviewer read the articles in a different order to prevent fatigue-related bias toward the end of the article set (AA read in alphabetical order by author last name; JL read in reverse alphabetical order by author last name; NA read in random order). Google Forms™, a web-based interface, was used to extract curricular details. General information about the curricula (e.g., country, institution, specialty, requirement, duration, teaching methods) was gathered as done in the preceding systematic review. We also extracted details of skills-based “advocacy tools” (e.g., legislative advocacy, community partnership, etc) and looked at knowledge-based “content areas” (e.g., SDOH, health equity and racial justice, quality improvement as a systemic policy rather than a process, and major health legislation). Data was gathered on evaluation methods beyond the original review article.

Once data was comprehensively extracted from each article, two reviewers (NA, AA) conducted a detailed synthesis. Original articles were reviewed again, and discrepancies were discussed to resolve inconsistencies in analysis. Additional notes from each reviewer beyond evaluation of standard curricular components were summarized. A summary statement for each article was generated and analyzed for recurring themes in curricular design and implementation.

RESULTS

Our initial search produced 802 citations that were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion, with 126 articles identified for full text review. Twenty-five articles ultimately met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. A hand search of the bibliographies of these articles and a review of all articles citing the initial Howell study produced an additional 65 citations of which one met all inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

The final set of 26 included articles represented 31 total GME curricula, as two articles (Vance and Kennedy) each detailed the same set of seven unique Psychiatry curricula. Table 1 summarizes the content and logistical structure for each included curriculum. US-based programs accounted for the majority of curricula (30 of 31); only one was from Canada. Curricula were most commonly found in Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, Pediatrics, and Psychiatry programs with only 16% representing other specialties, including Obstetrics and Gynecology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Preventive Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties.

Curricular Methods, Tools, and Content

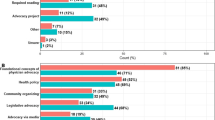

Curricular details on teaching methods, skills-based advocacy tools, and knowledge-based advocacy and policy content areas are shown in Table 2. Table 3 summarizes frequency of specific characteristics across curricula.

Teaching Methods

The most frequently used educational methods were experiential learning and lectures, followed by small group discussions. 77% of curricula (n = 24) described using multiple teaching methods, with 52% (n = 15) using both experiential learning and didactics (lecture, small group, or both). Projects were also a common tactic, with 38% (n = 24) of curricula utilizing individual and/or group projects. Only one curriculum reported using web-based modules39. Other unique educational methods described included panel debate40, writing an online blog29, developing advocacy alerts,17 and coaching.11

Skills-Based Advocacy Tools

Nearly all (94%, n = 29) of the curricula taught participants at least one advocacy tool, with 55% (n = 17) teaching more than one tool. Legislative advocacy skills, community partnership strategies, and advocacy writing (including op-eds, testimony, and other persuasive writing techniques) were most common. Some curricula utilized specific frameworks to teach specific tools (e.g., Asset-Based Community Development42 or Community-Based Participatory Research39 for community partnership) whereas others provided a broad overview of physician advocacy methods.14 Other unique tools included grant writing18 and legal research tools.19

Knowledge-Based Advocacy and Policy Content Areas

In addition to teaching tools needed to conduct advocacy work, 68% (n = 21) of curricula also covered specific topics relevant to advocacy and policy. Themes of inequity and social justice were prominent: SDOH and health equity/racial justice were the two most frequently taught topics, and four curricula taught structural competency. 60% (n = 19) of curricula included at least one of these three topics. Fewer curricula taught general health policy topics, with just 20% (n = 7) including quality improvement, healthcare finance, and/or major legislation (e.g., Affordable Care Act). Most curricula teaching legislative advocacy discussed local and state-level legislative pieces rather than national pieces of healthcare legislation. Several curricula included specific policy content on areas relevant to their specialties, such as mental health policy or child health policy topics (e.g., gun safety, SIDS, nutrition, etc), either alone or as part of broader themes on SDOH.

Evaluation Methods

The considerable heterogeneity between the articles and the elements of curricular design and evaluation included in them limited our ability to evaluate the quality of each study using any standard scale. We did, however, assess articles on their evaluation techniques as one measure of quality. Each article was given a quality score based on the characteristics of their evaluation (A for multimodal evaluation, B for single method of evaluation, and C for no evaluation) (Table 4). A majority (68%, n = 21) of the articles reported results of a formal evaluation with many (42%, n = 13) engaging in multimodal evaluation methods. All reported evaluations focused on trainee perceptions and satisfaction, while 67% (n = 14) also reported on trainee knowledge and skill acquisition. Many of these evaluations were conducted via surveys (48%, n = 14), either pre- and post-curriculum surveys or post-curriculum surveys alone. A variety of qualitative methods, including focus groups and interviews, were also used to elicit feedback from participants and stakeholders such as community partners. Unique quantitative methods included differences in RVUs in a clinical setting,10 measures of blog success based on readership and media references to posts, and various measures of participant outcomes such as grant success, future degree acquisition, or advocacy career paths. Consideration for long-term impact and residents’ interest and likelihood to continue advocacy efforts beyond residency was given7 although not consistently measured.

Core Elements of Curricular Design and Implementation

All included articles reflected upon lessons learned in curricular design and implementation based on evaluation results and the practical experience of leading advocacy curricula. We extracted recurrent themes meaningful for advocacy education.

Creating an Overarching Culture Supportive of Advocacy Education

Multiple articles highlighted the importance of GME programs creating buy-in for advocacy education by establishing a culture that supports advocacy training and efforts14–16,19,21,26. Early introduction of curricula16 was thought to promote advocacy-related knowledge acquisition, skill-building, and bonding10,11 and ultimately increase engagement in advocacy efforts throughout training.17 Some authors found that curricula should ideally be longitudinal with competency progression as a core component20,26.

Designation of resident and faculty champions13,14,21,27,29 was identified by several articles as a key strategy to promote curricular success and sustainability. Highlighting advocacy opportunities and outcomes at meetings, on program websites, and through listservs21,26 and providing platforms to share advocacy projects long-term26 were tools used to increase visibility and accessibility of advocacy-focused work, limit activation energy and encourage participation in this work14,15,17,21,26, reflect program identity to residency applicants during recruitment7,18,21,26,31, and promote longevity of efforts26.

Several publications discussed collaboration culture and reported that trainees benefit from working with other GME-level trainees7,40 across specialties21, participating in interdisciplinary16 and interprofessional9,15 teams, and engaging in systems-based learning9,15. Collaboration with the broader community, including other institutions and professional organizations11,20, was also helpful, especially when access to local advocacy resources was limited for various reasons, including geographic location15,19.

Designing Curricula to be Learner-Centric

Strategies to ensure that advocacy curricula are tailored to learner needs and interests were presented in several articles. Many emphasized the need for protected time to participate in offered curricula12,15,17,19–21,27,42, specifically recommending designated rotation blocks7,10,18,26,41, existing noon conferences13,16,20, academic half days15,16, and meals during meetings7,11,12,21 as strategies to facilitate curricular engagement. Recruitment of additional trainees to participate in advocacy endeavors was suggested to decreased burden of participation on trainees18.

Many authors proposed tactics to make advocacy education relevant and attainable to trainees. Several curricula recommended that educators explicitly discuss how developed skills can be applied in a medical career9,12,14 and emphasize that advocacy is achievable and important to physician identity irrespective of career path13. Establishing realistic and attainable goals, keeping the scope of projects feasible42, and allowing sufficient time for preparation of deliverables42 were methods used to prevent defeatism and burnout12. Clearly describing the objectives of curricular components and practical experiences upfront26,32,42, providing advance briefings42, and labeling advocacy activities as such15 enhanced trainees’ understanding of curricular purpose and intended impact.

In terms of outcomes, building and utilizing skill checklists20 were a suggested tool to track achievement. Scholarly opportunities were shown to be of importance to trainees21,27,29,31, and articles described ways to ensure trainees saw academic benefit from their advocacy education (e.g., residents interested in pursuing fellowship could combine advocacy efforts with research interests to produce scholarly work)7. Provision of academic recognition promoted a sense of achievement and career advancement7.

Articles described the importance of making curricula responsive to trainees. Explicitly recognizing trainee discomfort in engaging with advocacy education, creating supportive spaces for discussion and reflection13, and guiding learners through conversations regarding issues, challenges, and experiences in advocacy work26,32,42 were key themes. Authors recommended that educators discuss relevant facts in a manner that creates empathy for divergent viewpoints while dispelling incorrect preconceived notions and decreasing bias40. Providing feedback and tools to overcome barriers to successful advocacy was additionally supportive14.

Articles also described ways to make curricula adaptable to evolving learner needs14,21,31. Soliciting feedback from learners and then incorporating reported interests into curricular elements (e.g., selecting guest speakers—legislators, community activists, journalists, etc.—using trainee input)15,21, supporting trainee autonomy and ownership of advocacy work, and providing options (e.g., option to do projects individually or in small groups, option of topics for projects, etc) were strategies to customize the experience and make it more relevant15,40.

Supporting Educators

Educators trained in teaching advocacy are limited in number14,16,18,19,21, and several articles suggested that protected time for advocacy educators14,19 could facilitate curricular development, help existing instructors manage competing demands, and provide interested faculty time to gain relevant skills and experience21. Having multiple faculty facilitators for each curricular component also helped overcome logistical barriers associated with planning20, and some programs developed no- or low-cost10,17 curricular elements implementable without any faculty expertise.

Educators are expected to mentor trainees and role model constructive advocacy behaviors14, and a couple articles discussed strategies to support this role. One article recommended utilizing peer mentorship, group mentorship, and mentors outside the institution if advocacy champions are not immediately available14; another article recommended that programs provide clear expectations for faculty members regarding their specific mentorship responsibilities26.

Including Action-Oriented Components

Advocacy is a skills-based pursuit14, and trainees value real-world application of advocacy frameworks9,10,12,14 as well as active learning opportunities40. Thus, multiple articles suggested that educational efforts should focus on action and practical aspects of advocacy40 rather than discussions surrounding theoretical advocacy and political viewpoints14,40. Incorporation of action-oriented and timely topics was suggested as a potential strategy to improve attendance especially when residents are on busy rotations and less motivated to engage7.

Trainees often consider advocacy to be primarily patient-centered and individual-focused12,14,15. Several articles suggested integrating advocacy work with existing clinical responsibilities10 to make the impact of advocacy more visible12, bridge the gap between recognizing an issue and engaging in work that decreases disparities16,26, and support trainees in guiding tangible improvements in their clinical practice13,15,26. Taking these efforts a step further, community service opportunities may allow physicians to interact on a human level with their patients, adjusting the power dynamic that often exists in the clinical setting15 and moving trainees beyond a purely individual concept of advocacy. Multiple articles cautioned that advocacy activities involving patients and communities should adapt to their evolving needs12–16, engage nonclinical and community stakeholders28,31,42, minimize burden for community partners42, and demonstrate community impact18. Efforts should be sustainable for the community involved as well33. Care should be taken that efforts are patient-relevant and not just serving to address physician interests14.

Several curricula incorporated action-oriented activities beyond the community-level, most commonly utilizing field trips to state capitols as an experiential strategy to help learners practice persuasive legislative advocacy skills14,19,21; this strategy presented challenges though when instruction timing did not align with legislative windows19. Project-focused work potentially led to better outcomes such as increased camaraderie, leadership opportunities, and effectiveness7,40, but connecting trainees with longitudinal projects was sometimes time-consuming and may benefit from utilizing national networks over local ones moving forward7.

DISCUSSION

Advocacy is a core part of physician training that requires active instruction; it is no longer sufficient to assume trainees will acquire essential advocacy knowledge and skills through just passive exposure21. Authors of prior publications have sought to determine components of an ideal curriculum for advocacy education14,34,43–45, and our work builds upon this. Similar to Howell et al., we found that GME advocacy curricula most frequently focus on grassroots advocacy and community partnership, legislative advocacy, and persuasive communication in terms of topics covered, and most utilize lecture and experiential learning elements for teaching methods. While more curricula reviewed by Howell et al. included projects, our review showed that more recently published curricula instead include small group sessions. Specialties most represented in both reviews were Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Family Medicine while our updated review had substantial representation of curricula in Psychiatry as well. Both reviews noted heterogeneity in curricular evaluation methods while we further investigated the nature of the variability. Beyond the work of Howell et al., we found that content areas of most interest include social and structural determinants of health as well as health equity and racial justice. Our work also revealed additional insights regarding core features and components of GME advocacy curricula, building upon the work of Vance et al. (included in our review) who identified core components (didactics and experiential learning), attributes (practical, adaptive, patient-focused), and supports (champions, buy-in, and mentorship) across curricula in Psychiatry. Our common findings with these prior publications support the notion of an emerging consensus on core elements of advocacy curricula while our updated findings may reflect a shift in current advocacy teaching trends at the GME level.

We have combined our findings with the results of prior publications to propose an innovative and integrative framework grounded in experience that can be used to support and sustain advocacy education for GME trainees (Fig. 2). We specifically propose that programs should create culture that supports advocacy curricula, recognizes the unique needs of learners and educators, focuses on action-oriented skill development, utilizes a variety of teaching methods and advocacy tools, incorporates content and topics of relevance and interest, and conducts evaluation of impact on trainees and communities. The elements of our framework importantly align with several ACGME core requirements for residents and fellows23,24 (Table 5) as well as Malcolm Knowles’s Adult Learning Theory.

An overarching GME culture supportive of advocacy education and efforts is foundational to building curricula that are sustainable longitudinally. Trainee engagement in curricular elements requires time, and creation and delivery of curricular content are highly time-intensive. We support the call of multiple authors that programs should provide protected time for both trainees and educators. Skilled instructors are limited and should be considered a valuable asset.

Multiple curricula explicitly state the need for combining didactics with experiential learning, but we propose that the addition of action-oriented project-based work, whether completed individually or in groups, is also important. Most curricula include didactics, which can be incorporated into existing lecture/conference time to provide learners with protected time. Experiential learning opportunities can be incorporated with clinical duties to increase trainee connection with clinical work. Project-based work and community collaboration often go together although this is not necessary. Only one curriculum we reviewed utilized web-based modules although, since the COVID-19 pandemic, this is likely not representative of the current state of advocacy education.

Beyond op-ed writing, writing tools in general are considered important. Media engagement strategies, such as social media posts, overlap with writing skills. Many curricula and associated projects depend on funding from various grants7,11,13,20,27,28,42, and it is likely beneficial to specifically include grant-writing skills in advocacy curricula18.

In terms of content, health disparities in marginalized populations are of frequent interest28,32. Curricula should likely also teach advocacy ethics19 although this was only highlighted in a few articles.

Evaluation is generally lacking; most curricula utilize surveys to elicit trainee feedback and perceptions rather than objectively measure attainment of knowledge and skills. This area can use focus as advocacy is an action-oriented, skills-based pursuit. We recommend educators utilize Levels 3 and 4 of the Kirkpatrick Model of Evaluation to collect data during and after GME training to gain insight into the usefulness and utilization of advocacy skills learned in training11,13,18,20,26,29,31 and the impact of training on patient and community health8,31.

Our proposed framework is a starting point that we hope will generate a broad structure for advocacy curricula that can be adapted by individual programs. A future consensus process to affirm and finalize this structure is necessary as the degree to which our findings represent a complete landscape of GME advocacy curricula is limited by several factors. Our search extracted only published curricula, meaning valuable information from unpublished curricula was not available for analysis. There were likely also articles that discussed advocacy tools and content without labeling them as such and were thus not captured in our search despite our attempts to use inclusive search terms. Of the curricula we did capture, some articles lacked significant details, so the actual curricula may have included methods, tools, and content areas not reflected in our analysis. Most articles discussed a single curriculum at one institution, so results may not be generalizable although we attempted to address this by primarily extracting themes discussed across multiple publications.

Although our data represents a majority of Psychiatry curricula given the work of Vance et al. and Kennedy et al., Pediatrics is often regarded as having the most well-developed advocacy curricula, which may be secondary to the ACGME’s explicit requirement for pediatric trainees to learn about advocacy. In the future, explicit recognition of advocacy education as essential by the ACGME can enhance the presence and efficacy of advocacy curricula across specialties21. Resources and support from national organizations can also be helpful21. While our work adds to prior studies to determine effective teaching methods, core advocacy tools, and important content areas, further work is necessary to make sure these findings are truly representative of advocacy curricula being developed and taught across GME.

CONCLUSION

Modern physicians must demonstrate proficiency in advocacy skills to meaningfully care for their patients and patient populations; incorporating formal, comprehensive advocacy curricula into GME programs can facilitate competency achievement. Our findings from a systematic review of recently published GME advocacy curricula, combined with findings from previously published curricula, reveal recurrent core components that can be used to develop foundational advocacy education modules for dissemination and adaptation across GME programs. These include building program culture supportive of advocacy education; designing curricula to be action-oriented and mindful of learner and educator needs; utilizing didactics, experiential learning, and projects to teach advocacy; covering advocacy tools including legislative advocacy, community partnership, persuasive writing, and research methods; and teaching social and structural determinants of health, health equity, and racial justice. Next steps are to build expert consensus on core features and components of advocacy curricula and utilize our proposed framework to design standardized advocacy modules and mitigate some of the repetitive burden that educators face in teaching advocacy.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics 2022. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/320_pediatrics_2022.pdf. Accessed on June 13, 2023.

American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP Advocacy Guide: Pointing you in the right direction to become an effective advocate. 2009. Available at www.aap.org/moc/advocacyguide. Accessed on June 13, 2023.

ABIM Foundation, et al. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(3):243–6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012

American Medical Association. Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract with Humanity. Mo Med 2002;99(5):195.

Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: Physician Advocacy: What Is It and How Do We Do It? Acad Med 2010;85(1):63-7. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40.

American Psychiatric Association. APA Commentary on Ethics in Practice. 2015. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/file%20library/psychiatrists/practice/ethics/apa-commentary-on-ethics-in-practice.pdf. Access on June 13, 2023.

Andrews J, Jones C, Tetrault J, Coontz K. Advocacy Training for Residents: Insights From Tulane’s Internal Medicine Residency Program. Acad Med 2019;94(2):204-207. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002500.

Goss E, Iyer S, Arnsten J, Wang L, Smith CL. Liberation Medicine: a Community Partnership and Health Advocacy Curriculum for Internal Medicine Residents. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(10):3102-3104. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05518-1.

Neff J, Holmes SM, Knight KR, et al. Structural competency: curriculum for medical students, residents, and interprofessional teams on the structural factors that produce health disparities. MedEdPORTAL 2020;16:10888.

Sieplinga K, Disbrow E, Triemstra J, van de Ridder M. Off to a Jump Start: Using Immersive Activities to Integrate Continuity Clinic and Advocacy. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2021;8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205211059652

Emery EH, Shaffer JD, McCormick D, et al. Preparing doctors in training for health activist roles: a cross-institutional community organizing workshop for incoming medical residents. MedEdPORTAL 2022;18:11208.

Campbell M, Didwania A. Health Equity in Graduate Medical Education: Exploring Internal Medicine Residents’ Perspectives on a Social Determinants of Health Curriculum. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2020;31(4s):154-162. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2020.0147.

Lax Y, Braganza S, Patel M. Three-Tiered Advocacy: Using a Longitudinal Curriculum to Teach Pediatric Residents Advocacy on an Individual, Community, and Legislative Level. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2019;6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519859300

Vance MC, Kennedy KG. Developing an Advocacy Curriculum: Lessons Learned from a National Survey of Psychiatric Residency Programs. Acad Psychiatry 2020;44(3):283-288. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-020-01179-z.

Ying Y, Seabrook C. Health Advocacy Competency: Integrating Social Outreach into Surgical Education. J Surg Educ 2019;76(3):756-761. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.11.006.

Khera SP, Chung JJ, Daw M, Kaminski MA. A Framework and Curriculum for Training Residents in Population Health. Population Health Management 2022;25(1):57-64. (Article) (In English). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2021.0079.

Teran PR, Wong R, Van Ramshorst RD, et al. Evaluation of Legislative Advocacy Alerts for Pediatric Residents. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2020;59(4-5):500-504. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922820904596.

Pak-Gorstein S, Batra M, Johnston B, et al. Training Pediatricians to Address Health Disparities: An Innovative Residency Track Combining Global Health With Community Pediatrics and Advocacy. Acad Med 2018;93(9):1315-1320. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002304.

Piel J. Legislative Advocacy and Forensic Psychiatry Training. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2018;46(2):147-154. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.29158/jaapl.003741-18.

Majeed A, Newton H, Mahesan A, Vazifedan T, Ramirez D. Advancing Advocacy: Implementation of a Child Health Advocacy Curriculum in a Pediatrics Residency Program. MedEdPORTAL 2020;16:10882. Available at: https://www.mededportal.org/doi/epdf/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10882. Accessed June 13, 2023.

Kennedy KG, Vance MC. Resource document: advocacy teaching in psychiatry residency training programs. 2018. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Directories/Library-and-Archive/resource_documents/2018-Resource-Document-Advocacy-Teaching-in-Psychiatry-Residency-Training.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2023.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. CanMEDS: Better standards, better physicians, better care. Available at https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e. Accessed June 13, 2023.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). 2022. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2023.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Fellowship). 2022. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprfellowship_2022v3.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2023.

Fried JE, Shipman SA, Sessums LL. Advocacy: Achieving Physician Competency. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:2297-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05278-y

Knox KE, Lehmann W, Vogelgesang J, Simpson D. Community Health, Advocacy, and Managing Populations (CHAMP) Longitudinal Residency Education and Evaluation. J Patient Cent Res Rev 2018;5(1):45-54. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.17294/2330-0698.1580.

Traba C, Pai S, Bode S, Hoffman B. Building a Community Partnership in a Pandemic: NJ Pediatric Residency Advocacy Collaborative. Pediatrics 2021;147:e2020012252. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-012252

Krishnaswami J, Jaini PA, Howard R, Ghaddar S. Community-Engaged Lifestyle Medicine: Building Health Equity Through Preventive Medicine Residency Training. Am J Prev Med 2018;55(3):412-421. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.012.

Jones KB, Fortenberry K, Sanyer O, Knighton R, Van Hala S. Creation of a Family Medicine Residency Blog. Int J Psychiatry Med 2018;53(5-6):427-435. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217418791457.

LaDonna KA, Watling CJ, Cristancho SM, Burm S. Exploring Patients’ and Physicians’ Perspectives About Competent Health Advocacy. Med Educ 2021;55(4):486-495. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14408.

Oldfield BJ, Clark BW, Mix MC, et al. Two Novel Urban Health Primary Care Residency Tracks That Focus On Community-Level Structural Vulnerabilities. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33(12):2250-2255. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4272-y.

Bromage B, Encandela JA, Cranford M, et al. Understanding Health Disparities Through the Eyes of Community Members: a Structural Competency Education Intervention. Acad Psychiatry 2019;43(2):244-247. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-018-0937-z.

Whetstone S, Autry M. Linking Global Health to Local Health Within an Ob/Gyn Residency Program. AMA J Ethics 2018;20(1):253-260. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.3.medu1-1803.

Howell BA, Kristal RB, Whitmire LR, Gentry M, Rabin TL, Rosenbaum J. A Systematic Review of Advocacy Curricula in Graduate Medical Education. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(11):2592-2601. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05184-3.

Finkbeiner C, Doria C, Ellis-Kahana J, Loder CM. Changing obstetrics and gynecology residency education to combat reproductive injustice: a call to action. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2021;137(4):717-722.

Janeway M, Wilson S, Sanchez SE, Arora TK, Dechert T. Citizenship and Social Responsibility in Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg 2022;157:532-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.0621

Wright LS, Louisias M, Phipatanakul W. The United States’ reckoning with racism during the COVID-19 pandemic: what can we learn and do as allergist-immunologists? The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2021;147(2):504.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-Duplication of Database Search Results for Systematic Reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 2016;104(3):240-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014.

Gimpel N, Pagels P, Kindratt T. Community Action Research Experience (CARE): Training Family Physicians in Community Based Participatory Research. Educ Prim Care 2017;28(6):334-339. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2017.1295789.

Hirsch MA, Nguyen VQ, Wieczorek NS, Rhoads CF, Weaver PR. Teaching health care policy: using panel debate to teach residents about the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. MedEdPORTAL 2017;13:10655.

Michelson CD, Dzara K, Ramani S, Vinci R, Schumacher D. Keystone: Exploring Pediatric Residents’ Experiences in a Longitudinal Integrated Block. Teach Learn Med 2019;31(1):99-108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1478732.

Webber S, Butteris SM, Houser L, Coller K, Coller RJ. Asset-Based Community Development as a Strategy for Developing Local Global Health Curricula. Acad Pediatr 2018;18(5):496-501. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.001.

Coutinho AJ, Nguyen BM, Kelly C, et al. Formal Advocacy Curricula in Family Medicine Residencies: a CERA Survey of Program Directors. Fam Med 2020;52(4):255-261. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2020.591430.

Flynn L, Verma S. Fundamental Components of a Curriculum for Residents in Health Advocacy. Med Teach 2008;30(7):e178-83. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802139757.

McDonald M, Lavelle C, Wen M, Sherbino J, Hulme J. The State of Health Advocacy Training in Postgraduate Medical Education: a Scoping Review. Med Educ 2019;53(12):1209-1220. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13929.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Benjamin A. Howell and Mark Gentry for their collaboration and their team for conducting the initial work off of which our work is based. Part of Dr. Arons’s time for this project was funded by HRSA training grant T32HP19025 and the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of California San Francisco.

Funding

Part of Dr. Arons’s time for this project was funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) through grant number T32HP19025. The contents above are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agrawal, N., Lucier, J., Ogawa, R. et al. Advocacy Curricula in Graduate Medical Education: an Updated Systematic Review from 2017 to 2022. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 2792–2807 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08244-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08244-x