Abstract

Background

Professionalism standards encourage physicians to participate in public advocacy on behalf of societal health and well-being. While the number of publications of advocacy curricula for GME-level trainees has increased, there has been no formal effort to catalog them.

Objective

To systematically review the existing literature on curricula for teaching advocacy to GME-level trainees and synthesize the results to provide a resource for programs interested in developing advocacy curricula.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify articles published in English that describe advocacy curricula for graduate medical education trainees in the USA and Canada current to September 2017. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts to identify articles meeting our inclusion and exclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. We abstracted information and themes on curriculum development, implementation, and sustainability. Learning objectives, educational content, teaching methods, and evaluations for each curriculum were also extracted.

Results

After reviewing 884 articles, we identified 38 articles meeting our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Curricula were offered across a variety of specialties, with 84% offered in primary care specialties. There was considerable heterogeneity in the educational content of included advocacy curriculum, ranging from community partnership to legislative advocacy. Common facilitators of curriculum implementation included the American Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements, institutional support, and preexisting faculty experience. Common barriers were competing curricular demands, time constraints, and turnover in volunteer faculty and community partners. Formal evaluation revealed that advocacy curricula were acceptable to trainees and improved knowledge, attitudes, and reported self-efficacy around advocacy.

Discussion

Our systematic review of the medical education literature identified several advocacy curricula for graduate medical education trainees. These curricula provide templates for integrating advocacy education into GME-level training programs across specialties, but more work needs to be done to define standards and expectations around GME training for this professional activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND

Physician professional responsibilities extend beyond clinical practice and include an advocacy role focused on the promotion of societal health and well-being.1, 2 This position has been affirmed by the American Medical Association (AMA) in its Declaration on Professional Responsibility, which stated that physicians must “advocate for the social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”3 And many other authors and professional medical organizations have also argued for the importance of public advocacy as a professional obligation.4,5,6

It has been suggested that knowledge, skills, and attitudes around advocacy should be explicitly incorporated into graduate medical education.4, 7 Graduate medical education (GME) training is an important venue for such interventions as it is the time when professional attitudes and behaviors are solidified. Often trainees enter residency with prior experiences in advocacy and a desire to continue that work; however, this interest drops during residency.8, 9 Given this decline, it is not surprising that few physicians maintain an advocacy role after training, despite an understanding of the importance and desire to be public advocates.10, 11 Importantly, residents exposed to advocacy in GME training are more likely to incorporate these activities into their future careers.12, 13

The American Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in the USA14 and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons (RCPS) in Canada15 recognize training in advocacy as an objective of graduate medical education. Several specialties have amplified this call and have explicitly included educational and training experiences around advocacy in their ACGME program requirements.16 Not surprisingly, when included as a program requirement, such as in pediatrics, most programs subsequently include advocacy training into their training program.17

Individual residency programs have included training on the public role of physicians in their communities for many years,18, 19 although there has only recently been a push to standardize advocacy training.4, 7, 20, 21 Currently, there are no shared standards across specialties to guide the content of this type of training.22 While the focus of advocacy efforts may differ between specialties, standards and the tools to teach the attitudes, skills, and knowledge for advocacy training are not specialty specific and can be shared. While there have been surveys of the inclusion of advocacy into residency training,9, 17, 23 to date, there is no systematic review of published literature on GME-level educational interventions on physician advocacy.

The goal of our study was to (1) systematically review the existing literature regarding curricula for teaching advocacy to GME-level trainees and (2) synthesize this information into a resource for programs interested in developing advocacy curricula.

METHODS

A medical librarian (MG) conducted systematic literature searches in Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) databases. Citations were included current to September 2017. A combination of controlled vocabulary and free text words and phrases was used in the searches. Concepts included graduate medical education, curriculum, advocacy, community engagement, lobbying, human rights, social justice, and community-based participatory research (Online Appendix 1). Other sources of peer-reviewed medical educational literature were hand-searched, such as MedEdPORTAL (AAMC, Washington, DC), using similar search terms to identify interventions published prior to September 2017. In addition, bibliographies of included articles were hand-searched to identify articles that were otherwise not identified. The articles were then uploaded into a systematic review software for title/abstract evaluation (Covidence, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia).

We included articles that described formal educational curricula that incorporated an explicitly stated objective focusing on improving trainees’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes around advocacy. For this review, we utilized the definition of advocacy developed by Earnest et al.: “action by a physician to promote social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being.”4 We included activities that focused on systemic changes that affect population- or community-level health outcomes beyond hospital- or clinic-level interventions. These encompassed domains of public policy advocacy, legislative advocacy, grassroots organizing, and partnerships with non-medical community groups on community-level health interventions. Educational initiatives that were limited to quality improvement, hospital/clinic-based population health, or individual patient advocacy were excluded. Many of the studies we reviewed involved engagement with community organizations. In order to focus on efforts to actively change systems in non-clinical settings, we included curriculum that involved partnerships with community organizations and excluded those that were limited to exposing trainees to community resources.

We included only educational interventions for trainees in graduate medical education (residents or fellows) but did not limit by specialty. We included only programs in Canada and the USA given the similarities in medical training in these two countries. We included only articles published in English and did not exclude articles based on types, length, or quality of the educational intervention, or absence of formal evaluation.

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts to identify articles meeting the inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. The full texts of the abstracts which screened positive were then independently reviewed by two reviewers to assess for inclusion, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. (BH, TR, LW, RK reviewed titles/abstracts and full text articles).

For all articles that met our inclusion criteria, we extracted data via an online form. Elements for data extraction were determined by a review of the educational literature and author consensus. We (BH, LW, RK) extracted information on the country, specialty, and description of the training programs. We also extracted information on curricular requirements, learning objectives, educational strategies, role of community partners, curriculum development, evaluation methods, and resources utilized. Finally, we included a brief synopsis of each curricular offering. If information was not included in the published article, it was coded as “unclear” in our extraction tool. In addition, we calculated summary statistics of included articles. The denominator for these summary statistics included only articles from which relevant information could be ascertained from the published manuscript.

We supplemented the structured data collection with a thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences in objectives, implementation, and evaluation of the included educational interventions. One of us (BH) developed a framework for the thematic analysis after an initial reading of all the included studies. Subsequently, the framework was reviewed by the team and then applied to each study to extract common themes (BH, LW independently coded all studies). We then synthesized and described themes that emerged.

RESULTS

The initial search identified 884 references meeting our criteria; after eliminating duplicates, 724 articles were deemed irrelevant by screening of titles and abstracts (Fig. 1—PRISMA diagram). Of the 160 full-text articles assessed for inclusion, 132 articles were excluded and 28 articles were included. Reasons for exclusion included the following: (a) articles that did not describe a curriculum, (b) curricula that did not have advocacy as an explicit educational objective, (c) curricula that did not target graduate medical education, or (d) citations that did not have a full manuscript published (abstract only). Eight additional articles were identified via hand-searching the references of articles meeting our inclusion criteria. Two additional articles were identified in MedEdPORTAL. Ultimately, we included 38 articles in our data extraction and analysis. Articles included were published from 1985 to 2017 with 22 published from 2009 onward. Summarized findings from our data extraction are presented in Tables 1 and 2. There was considerable variability in the descriptions of curricula, which ranged from brief outlines of the covered topics to more in-depth, fully reproducible descriptions with included materials and lesson plans. This variability limited our ability to extract all the data points required to fully compare the included curricula.

Educational Setting and Teaching Methods

Accounting for overlap in the curricula described in the included articles, our review included descriptions of individual curricula from 32 distinct residency programs and three articles that described curricula at multiple institutions. Of these three, one described a curriculum developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Community Pediatrics Training Initiative (CPTI) which was not tied to a residency program,36 one described multiple curricula developed as part of the California Collaborative in Pediatrics and Legislative Advocacy,28 and one described a curriculum offered to all Canadian OB/Gyn programs.50

The described curricular interventions were offered across a variety of specialties including internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, and surgical specialties, although the majority were in primary care specialties (n = 31, 84% in pediatrics, internal medicine, or family medicine) with the largest number involving pediatric residents (n = 18), followed by internal medicine (n = 9) and family medicine (n = 8) (Table 2). Several curricula involved participants from multiple specialties, with one article describing a curriculum based in one residency program but open to participants from any specialty,35 and three articles describing shared resources within curricula required by different specialties within one institution.30, 49, 60 Another four articles described curricula in four separate specialty training programs at the same institution.24, 26, 44, 52 Thirty-two were from the USA, and 6 were from Canada.

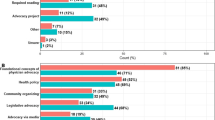

Teaching methodologies also varied, ranging from curricula that exclusively included didactic seminars and modules to curricula that were exclusively structured around experiential learning via mentored community-based advocacy projects (Table 2). Several curricula (n = 9) were structured around collective group projects with contribution from all participants. The majority included some component of didactic learning, and a majority included a component of experiential learning. There was also considerable heterogeneity in the structure and content of identified advocacy curricula. Thirty-one articles described curricula that were clearly identified as formal additions to the resident curriculum, and a minority were electives. The range of time committed to the curriculum ranged from one half day to 12 weeks.

Educational Content

In our thematic analysis, we noted a shared definition of advocacy on a general level, but significant variation in the application and specifics of that definition. Broadly speaking, all studies described advocacy as related to the role of physicians in recognizing and acting on community- and system-level factors that impact the health of their patients, outside of direct patient care. Aside from that, however, there was disagreement on where this action should be focused. Most, but not all, described advocacy as focusing on addressing health inequity and social determinants of health. And the curricula ranged from focusing on community-level collaboration and impact to influencing health policy on state and federal levels. Several studies, typically those that had more dedicated curricular time, attempted to address the spectrum of these forms of advocacy engagement.

There was no consistent set of educational content offered across curriculum, as this varied with the advocacy focus (community versus federal policy) (Table 2). Although a majority included training on partnerships with community organizations (n = 24), others focused exclusively on health policy/legislative advocacy. Among curricula that included partnerships with community organizations, the involvement of community organizations varied from providing brief lectures to serving as collaborative partners at training sites. A majority of curricula included a required community-partnered advocacy project (n = 22). Ten programs included content on legislative advocacy or an experience visiting a legislator or legislative body (state capital, Capitol Hill, etc.). A minority (n = 8) included training on persuasive communication, such as op-ed writing, media relations, or public speaking. Only three programs included content on grassroots advocacy or community organizing.27, 34, 46 Only one included research-based advocacy as a core topic,27 though several other articles described scholarly products of residents who had been through the curriculum.

Implementation and Sustainability

Among the studies included, there were several noted facilitators and barriers to the implementation of an advocacy curriculum. The role of accrediting bodies (ACGME, RCPS) in mandating advocacy training was noted as a facilitator for curricular development. In particular, the “health advocate” role within the CanMEDS framework and the ACGME Pediatric program requirements were a motivator for Canadian and US training programs, respectively. That said, most studies noted the lack of specificity in these mandates as a barrier to implementation.

Other facilitators included support from leadership, protected faculty time, direct funding (either grants such as Anne E. Dyson Community Pediatrics Training Initiative61 or from the medical school), and the availability of resources and skills within the faculty and community. In addition, four curricula involved formal collaboration with a professional organization, such as the state chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics,43, 47, 56, 62 with two curricula having been developed by a specialty-specific professional organization for its trainees.37, 50

The most common barriers referenced were the competing time demands and conflicts with clinical responsibilities. The culture of the training program, lack of local champions, and turnover in faculty and community partners were also noted as barriers to implementation. Among programs that included community partnerships, differences in expectations and culture between community partners, faculty, and trainees were noted as a barrier to implementation. Very few of the articles included information on the direct and/or indirect costs of curricular implementation, such as direct financial costs, faculty resources, lost clinical productivity, or administrative support.

Regarding sustainability, most of the articles described curricula implemented for three or fewer academic years (n = 27, 71%), and there were fewer emergent themes on facilitators and barriers on this topic. Among longer standing curricula, the integration of advocacy into the identity and values of the training program was noted as the most common facilitator to creating a sustainable curriculum. Turnover, especially in volunteer faculty and leadership, and stable funding sources were noted as barriers to sustainability.

Evaluation

Formal curricular evaluation was reported in 55% (n = 21) of articles, and no consistent form of evaluation was performed across the curricula. Evaluation most often included pre/post-test evaluation of resident report of self-efficacy, attitudes, or knowledge around advocacy, but no consistent sets of questions were utilized. Some articles included qualitative interviews, focus groups, or personal reflective documentation to assess the curriculum. When reported, trainee’s experience of advocacy curriculum was generally positive and appreciated. Most evaluation showed improvement of trainee’s attitudes, skills, and knowledge around advocacy, as well as increased sense of self-efficacy and reported likelihood to do advocacy in the future. Articles commonly reported on completion of community-partnered projects and research products as evidence of successful curriculum. A few articles reported on longer term outcomes, such as post-residency career choices, though these were not evaluated in a controlled, unbiased manner, and evaluation of other long-term outcomes was limited. There were no comparisons of different curricula to assess best practices for teaching advocacy.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this systematic review was to describe the spectrum of GME-level advocacy curricula that have been reported in the literature. We describe the range of educational methods, content, and experiences implementing and sustaining advocacy curricula for GME-level trainees, thus providing a resource for programs interested in integrating this type of training into their own residency programs. It is notable that multiple specialties have implemented advocacy curricula, ranging from family medicine to orthopedic surgery, although the majority were among primary care specialties (most commonly, pediatrics). A key observation that emerged in our review was the lack of a consistent body of knowledge or skill set, and a notable heterogeneity in the methodology and resources used across the curricula.

Efforts to include explicit advocacy training would benefit from continued development of standardized goals, content, and outcome measures to better correlate with stated educational objectives.7 While all the curricula shared a general definition of advocacy, the included advocacy examples varied across different settings. Our review points out some content areas that could potentially be included in a shared advocacy education framework. For example, most programs included partnership with community organizations and community-based advocacy projects as a core experiential educational component. The same could be said regarding the inclusion of knowledge and skills around legislative advocacy and persuasive communication.

The diversity of these described initiatives is, however, beneficial for programs seeking to incorporate advocacy training. Depending upon available resources, new programs can draw from a menu of potential curricular content and approaches to adapt to their needs. Given the limited description of resources required and short duration of most described curricula, however, there is a scarcity of information regarding the sustainability of these types of curricular efforts. Although many of the articles included formal evaluation, there was no consistent method used across articles, and the majority used pre/post-surveys of self-efficacy, skills, attitudes, and knowledge. A few assessed longer-term outcomes, such as post-residency career choices, but these were limited. Importantly, these long-term assessments were subject to selection bias, as it is likely that residency programs offering advocacy training attracted residents who were predisposed to participate in advocacy work following training, and these assessments lacked control groups. Given the inconsistency of evaluation methods, there is a need for standardization of objectives and assessments to facilitate comparisons across curricula.

The over representation of primary care specialties, especially pediatrics, likely represents the influence of two factors: first, prior adoption of community-oriented primary care and social medicine models, and second, the role of accrediting bodies. Several of the included curricula self-identified as teaching “community medicine,” “community-oriented primary care (COPC),” or “social medicine,” though our definition of advocacy certainly applied.18, 19 This was particularly relevant to the movement to increase community medicine training in the 1980s,63 and several of the curricula we identified were developed during this period.33, 34, 37, 38, 43, 48, 53, 57 These earlier trends in medical training, which were limited to primary care specialties, may explain the relative lack of advocacy curricula in non-primary care specialties. That said, some of the articles that we screened which reported on “community-oriented primary care” curricula did not include content on advocacy. This discrepancy points again to the importance of developing shared educational objectives and a definition of advocacy in this sphere.7, 22

Second, the over-representation of pediatrics training programs is notable and speaks to the role of accrediting bodies in driving curricular innovation. Since 2001, the ACGME Pediatric program requirements have required educational experiences that prepare residents for the role of advocate for the health of children in the community.16 Although several of the included curricula for pediatric trainees predated 2001, the majority were published after and directly referenced the inclusion of child advocacy in the requirements as part of the rationale for their creation.22, 24, 28, 32, 36, 38, 40, 41, 51, 56, 58 In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics directly supported residency programs through the Dyson Community Pediatrics Training Initiative (CPTI) 13, 28, 29, 36, 58 and provided other institutional support around the development and implementation of child advocacy curricula.61, 64 Published surveys of advocacy training among pediatric residency programs revealed shared educational objectives and content which may reflect success of these efforts by the AAP.17

There were several limitations of our study. First, as there is no standard definition of advocacy, it is possible that the definition we used for our inclusion criteria may have missed articles or curricula that would have been included under a different definition. We also excluded several articles that were descriptions of entire residency programs that likely included components of advocacy and community partnership but were excluded because they did not include descriptions of discrete curricula.19, 65, 66 We attempted to address limitations in our search methodology by hand-searching citations of articles that met our inclusion criteria, thereby expanding the scope of our search. We also limited our search to residency programs in the USA and Canada given the commonalities in GME training in these two countries, yet there is likely much to learn about teaching these skills in other training settings and other countries. As our article search was completed in 2017, we may have missed relevant studies published after that time. The heterogeneity of included articles limited our ability to synthesize our findings, though we have reported on common themes that emerged across the included articles. Finally, we acknowledge that by limiting our search to only the published literature, our review represents an under-sampling of GME curricular offerings in this area. Anecdotally, we are aware of several programs (ours included) that have developed curricula on this topic area that have not been published in the medical literature. This gap may lead to reporting bias, and unpublished curricula may systematically differ from those in the published literature, especially in reporting the facilitators and barriers to implementation in different settings. To improve GME-level advocacy training in the future, more work is needed to fill in knowledge about best practices.

CONCLUSION

Our systematic review of the medical education literature identified 38 GME-level advocacy curricula. These curricula were predominately from primary care specialties, likely due to historical precedents in these specialties. Educational content and teaching methods varied across curricular offerings, though often included a focus on community partnership. These curricula were well accepted by trainees, but evaluation was variable and limited.

Advocacy is an established professional responsibility, and all trainees should be educated in advocacy skills, knowledge, and attitudes. The collection of articles included here provides examples of curricular approaches for integrating advocacy education into GME training programs, irrespective of discipline. Future curricular efforts in this area would benefit from development of shared definitions, objectives, and standards. Finally, our findings speak to the important role that accrediting bodies can play across specialties to define standards and expectations for GME-level advocacy training.

References

Wynia MK, Latham SR, Kao AC, Berg JW, Emanuel LL. Medical professionalism in society. N Engl J Med 1999;341(21):1612–6.

Wynia MK, Papadakis MA, Sullivan WM, Hafferty FW. More than a list of values and desired behaviors: a foundational understanding of medical professionalism. Acad Med 2014;89(5):712–4.

American Medical Association. Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract with Humanity. Mo Med 2002;99(5):195.

Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: Physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med 2010;85(1):63–7.

ABIM Foundation, et al. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(3):243–6.

DuPlessis HM, Boulter CSC, Cora-Bramble D, et al. The Pediatrician’s Role in Community Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):1092–4.

Croft D, Jay SJ, Meslin EM, Gaffney MM, Odell JD. Perspective: is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med 2012 Sep;87(9):1165–70.

Stafford S, Sedlak T, Fok MC, Wong RY. Evaluation of resident attitudes and self-reported competencies in health advocacy. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:82.

Leveridge M, Beiko D, Wilson JW, Siemens DR. Health advocacy training in urology: a Canadian survey on attitudes and experience in residency. Can Urol Assoc J 2007;1(4):363–9.

Gruen RL, Campbell EG, Blumenthal D. Public roles of US physicians: community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2467–75.

Grande D, Armstrong K. Community volunteerism of US physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(12):1987–91.

Minkovitz CS, Goldshore M, Solomon BS, Guyer B, Grason H. Five-year follow-up of Community Pediatrics Training Initiative. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):83–90.

Shipley LJ, Stelzner SM, Zenni EA, Hargunani D, O’Keefe J, Miller C, et al. Teaching community pediatrics to pediatric residents: strategic approaches and successful models for education in community health and child advocacy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4 Suppl):1150–7.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements 2017. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed on May 9, 2019.

Frank, J. (Ed.). The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Available at: http://www.ub.edu/medicina_unitateducaciomedica/documentos/CanMeds.pdf. Accessed on May 9, 2019.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics 2017. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/320_pediatrics_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed on May 9, 2019.

Lichtenstein C, Hoffman BD, Moon RY. How do US pediatric residency programs teach and evaluate community pediatrics and advocacy training? Acad Pediatr 2017;17(5):544–9.

Mullan F. Community-oriented primary care: an agenda for the ‘80s. N Engl J Med 1982;307(17):1076–8.

Strelnick AH, Shonubi PA. Integrating community oriented primary care into training and practice: a view from the Bronx. Fam Med 1986;18(4):205–9.

Dharamsi S, Ho A, Spadafora SM, Woollard R. The physician as health advocate: translating the quest for social responsibility into medical education and practice. Acad Med 2011;86(9):1108–13.

Hubinette M, Dobson S, Scott I, Sherbino J. Health advocacy. Med Teach 2017;39(2):128–35.

Chamberlain LJ, Sanders LM, Takayama JI. Advocacy by any other name would smell as sweet. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(4):453.

Catalanotti JS, Popiel DK, Duwell MM, Price JH, Miles JC. Public health training in internal medicine residency programs: a national survey. Am J Prev Med 2014;47(5 Suppl 3):S360–7.

Au H, Harrison M, Ahmet A, et al. Residents as health advocates: The development, implementation and evaluation of a child advocacy initiative at the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario). Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(7):567–72.

Bachofer S, Velarde L, Clithero A. Laying the foundation: a residency curriculum that supports informed advocacy by family physicians. Am J Prev Med 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S312–3.

Bandiera G. Emergency medicine health advocacy: foundations for training and practice. CJEM. 2003;5(5):336–42.

Basu G, Pels RJ, Stark RL, Jain P, Bor DH, McCormick D. Training Internal Medicine Residents in Social Medicine and Research-Based Health Advocacy: A Novel, In-Depth Curriculum Acad Med 2017;92(4):515–20.

Chamberlain LJ, Sanders LM, Takayama JI. Child advocacy training: curriculum outcomes and resident satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005 Sep;159(9):842–7.

Chung E, Kahn S, Altshuler M, Lane JL, Plumb J. The JeffSTARS Advocacy and Community Partnership Elective: A Closer Look at Child Health Advocacy in Action. MedEdPORTAL. Available at: https://www.mededportal.org/publication/10526/. Accessed on May 9, 2019.

Cohen E, Fullerton DF, Retkin R, Weintraub D, Tames P, Brandfield J, et al. Medical-legal partnership: collaborating with lawyers to identify and address health disparities. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25(2):136–9.

Daniels AH, Bariteau JT, Grabel Z, DiGiovanni CW. Prospective analysis of a novel orthopedic residency advocacy education program. R I Med J (2013). ;97(10):43–6.

Delago C, Gracely E. Evaluation and comparison of a 1-month versus a 2-week community pediatrics and advocacy rotation for pediatric residents. Clin Pediatr 2007;46(9):821–30.

Donsky J, Villela T, Rodriguez M, Grumbach K. Teaching community-oriented primary care through longitudinal group projects. Fam Med 1998;30(6):424–30.

Fisher JA. Medical training in community medicine: a comprehensive, academic, service-based curriculum. J Community Health 2003;28(6):407–20.

Greysen SR, Wassermann T, Payne P, Mullan F. Teaching health policy to residents--three-year experience with a multi-specialty curriculum. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(12):1322–6.

Hoffman B, Rose J, Best D, Linton J, Chapman S, Lossius M, et al. The Community Pediatrics Training Initiative Project Planning Tool: A Practical Approach to Community-Based Advocacy. MedEdPORTAL. Available at: https://www.mededportal.org/publication/10630/. Accessed on May 9, 2019.

Hufford L, West DC, Paterniti DA, Pan RJ. Community-based advocacy training: applying asset-based community development in resident education. Acad Med 2009;84(6):765–70.

Kaczorowski J, Aligne CA, Halterman JS, Allan MJ, Aten MJ, Shipley LJ. A block rotation in community health and child advocacy: Improved competency of pediatric residency graduates. Ambul Pediatr 2004;4(4):283–8.

Kaprielian VS, Silberberg M, McDonald MA, Koo D, Hull SK, Murphy G, et al. Teaching population health: a competency map approach to education. Acad Med 2013;88(5):626–37.

Klein M, Vaughn LM. Teaching social determinants of child health in a pediatric advocacy rotation: small intervention, big impact. Med Teach 2010;32(9):754–9.

Kuo AA, Shetgiri R, Guerrero AD, et al. A public health approach to pediatric residency education: responding to social determinants of health. J Grad Med Educ 2011;3(2):217–23.

Long T, Chaiyachati KH, Khan A, Siddharthan T, Meyer E, Brienza R. Expanding Health Policy and Advocacy Education for Graduate Trainees. J Grad Med Educ 2014 Sep;6(3):547–50.

Lozano P, Biggs VM, Sibley BJ, Smith TM, Marcuse EK, Bergman AB. Advocacy training during pediatric residency. Pediatrics. 1994;94(4 I):532–6.

Martin D, Hum S, Han M, Whitehead C. Laying the foundation: teaching policy and advocacy to medical trainees. Med Teach 2013;35(5):352–8.

Michael YL, Gregg J, Amann T, Solotaroff R, Sve C, Bowen JL. Evaluation of a community-based, service-oriented social medicine residency curriculum. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2011;5(4):433–42.

Miller FA, Melton WD, Waitzkin H. An innovative community medicine curriculum: the La Mesa housecleaning cooperative. West J Med 2000;172(5):337–9.

Novotny TE, Seward J, Sun RK, Acree K. The “sausage factory” tour of the legislative process: an interactive orientation. Am J Public Health 1999;89(5):771–3.

Paterniti DA, Pan RJ, Smith LF, Horan NM, West DC. From physician-centered to community-oriented perspectives on health care: Assessing the efficacy of community-based training. Acad Med 2006;81(4):347–53.

Paul E, Fullerton DF, Cohen E, Lawton E, Ryan A, Sandel M. Medical-legal partnerships: addressing competency needs through lawyers. J Grad Med Educ 2009;1(2):304–9.

Posner G, Finlayson S, Luna V, Miller D, Fung-Kee-Fung M. Experiencing Health Advocacy During Cervical Cancer Awareness Week: A National Initiative for Obstetrics and Gynaecology Residents. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(7):633–8.

Roth EJ, Barreto P, Sherritt L, Palfrey JS, Risko W, Knight JR. A new, experiential curriculum in child advocacy for pediatric residents. Ambul Pediatr 2004;4(5):418–23.

Sharma M. Developing an integrated curriculum on the health of marginalized populations: successes, challenges, and next steps. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25(2):663–9.

Shope TR, Bradley BJ, Taras HL. A block rotation in community pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1999;104(1 Pt 2):143–7.

Tapia NM, Milewicz A, Whitney SE, Liang MK, Braxton CC. Identifying and Eliminating Deficiencies in the General Surgery Resident Core Competency Curriculum. JAMA Surg 2014;149(6):514–8.

Taylor BD, Buckner AV, Walker CD, Blumenthal DS. Faith-based partnerships in graduate medical education: The experience of the Morehouse School of Medicine Public Health/Preventive Medicine Residency Program. Am J Prev Med 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S283–9.

Varkey P, Billings ML, Matthews GA, Voigt RG. The power of collaboration: Integrating a preventive medicine-public health curriculum into a pediatric residency. Am J Prev Med 2011;41(4 SUPPL. 3):S314-S6.

Werblun MN, Dankers H, Betton H, Tapp J. A structured experiential curriculum in community medicine. J Fam Pract 1979;8(4):771–4.

Willis E, Frazier T, Samuels RC, Bragg D, Marcdante K. Pediatric residents address critical child health issues in the community. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2007;1(3):273–80.

Zakaria S, Johnson EN, Hayashi JL, Christmas C. Graduate Medical Education in the Freddie Gray Era. N Engl J Med 2015 Nov 19;373(21):1998–2000.

Kaczorowski J, Aligne CA, Halterman JS, Allan MJ, Aten MJ, Shipley LJ. A block rotation in community health and child advocacy: Improved competency of pediatric residency graduates. Ambul Pediatr 2004;4(4):283–8.

American Academy of Peditrics. Dyson Community Pediatrics Training Initiative. Available at: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/CPTI/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Mitchell JD, Parhar P, Narayana A. Teaching and assessing systems-based practice: A pilot course in health care policy, finance, and law for radiation oncology residents. J Grad Med Educ 2010;2(3):384–8.

Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1996.

Kaczorowski J. Pediatrics in the community: community pediatrics training initiative (CPTI). Pediatr Rev 2008 Jan;29(1):31–2.

Strelnick AH, Swiderski D, Fornari A, Gorski V, Korin E, Ozuah P, et al. The residency program in social medicine of Montefiore Medical Center: 37 years of mission-driven, interdisciplinary training in primary care, population health, and social medicine. Acad Med 2008;83(4):378–89.

Furin JJ, Farmer P, Wolf M, et al. A novel training model to address health problems in poor and underserved populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2006;17(1):17–24.

Contributors

There were no significant contributors to this manuscript outside of those included in the authorship group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howell, B.A., Kristal, R.B., Whitmire, L.R. et al. A Systematic Review of Advocacy Curricula in Graduate Medical Education. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 2592–2601 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05184-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05184-3