Abstract

Background

By 2030, the number of US adults age ≥65 will exceed 70 million. Their quality of life has been declared a national priority by the US government.

Objective

Assess effects of an eHealth intervention for older adults on quality of life, independence, and related outcomes.

Design

Multi-site, 2-arm (1:1), non-blinded randomized clinical trial. Recruitment November 2013 to May 2015; data collection through November 2016.

Setting

Three Wisconsin communities (urban, suburban, and rural).

Participants

Purposive community-based sample, 390 adults age ≥65 with health challenges. Exclusions: long-term care, inability to get out of bed/chair unassisted.

Intervention

Access (vs. no access) to interactive website (ElderTree) designed to improve quality of life, social connection, and independence.

Measures

Primary outcome: quality of life (PROMIS Global Health). Secondary: independence (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living); social support (MOS Social Support); depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-8); falls prevention (Falls Behavioral Scale). Moderation: healthcare use (Medical Services Utilization). Both groups completed all measures at baseline, 6, and 12 months.

Results

Three hundred ten participants (79%) completed the 12-month survey. There were no main effects of ElderTree over time. Moderation analyses indicated that among participants with high primary care use, ElderTree (vs. control) led to better trajectories for mental quality of life (OR=0.32, 95% CI 0.10–0.54, P=0.005), social support received (OR=0.17, 95% CI 0.05–0.29, P=0.007), social support provided (OR=0.29, 95% CI 0.13–0.45, P<0.001), and depression (OR= −0.20, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.01, P=0.034). Supplemental analyses suggested ElderTree may be more effective among people with multiple (vs. 0 or 1) chronic conditions.

Limitations

Once randomized, participants were not blind to the condition; self-reports may be subject to memory bias.

Conclusion

Interventions like ET may help improve quality of life and socio-emotional outcomes among older adults with more illness burden. Our next study focuses on this population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov; registration ID number: NCT02128789

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Quality of life (QOL) is a broad concept, encompassing many mental and physical variables. According to a survey of 7400 older adults from 22 countries, its most valued aspects later in life are feelings of energy and happiness, ability to complete activities of daily living, independence, general health, and mobility.1 Other research with older adults indicates that QOL is strongly negatively predicted by depression,2 loneliness,3 pain and functional limitations,4 and dependence on others.5 In one telling study, 80% of 194 older women said they would rather die than experience the reduced quality of life that would result from a hip fracture requiring admission to a nursing home.6

By 2030, the number of US adults age 65 and older will exceed 70 million.7 The Department of Health and Human Services’ latest decennial report, Healthy People 2020, states that improving QOL for older adults is a chief goal in the next decade, for the sake of both individual patients and the US healthcare infrastructure, which is increasingly strained as the population ages.8 The current article reports on a randomized clinical trial of an online intervention designed to sustain or improve QOL among this growing cohort.

eHealth interventions to improve QOL have typically targeted a narrow range of outcomes (e.g., chronic pain, exercise, blood pressure, loneliness).9,10,11,12,13,14 Among studies focused on older adults, most have relied on small samples and quasi-experimental or non-equivalent control group designs.14 In a notable exception, Czaja randomized 300 older adults to receive the online Personal Reminder Information and Social Management (PRISM) system versus printed health-related information. PRISM included links to health-related information and local resources, email, games, and tutorials. At 6 months, the PRISM group (vs. control) reported less loneliness and more social support and well-being. These differences were no longer significant at 12 months.15

The current trial builds on this work, examining the effects of ElderTree (ET), an interactive website addressing key components of older adults’ QOL. ET’s design draws upon self-determination theory (SDT), which posits that feelings of competence, social connection, and intrinsic motivation or autonomy contribute to mental health, well-being, and QOL.16,17,18 ET aligns with the theory by providing information (promoting feelings of competence), connections to other seniors coping with similar issues (promoting social connection), and tools to aid self-management of health (promoting autonomy). SDT has been chosen as the theoretical basis because it is both broad and fundamental enough to underpin a complex, multifaceted eHealth intervention such as ET.

This was a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of older adults living in their homes. We hypothesized that those assigned to ET (vs. control) would show greater improvements over time in the primary outcome of QOL and secondary outcomes of independence, falls prevention, social support, and depression. We predicted that age, sex, and health indicators (risk factors, healthcare use) would moderate the impact of the study arm on these outcomes (Fig. 1). All outcomes were assessed at baseline, 6, and 12 months using validated measures.

METHODS

Trial Design and Participants

This was a non-blinded randomized clinical trial allocating 390 older adults equally (1:1) to the intervention (ET plus participants' usual access to information and communication) or control (participants’ usual access to information and communication only). Participants were recruited from November 2013 to May 2015 from three Wisconsin communities (one urban, one suburban, one rural) for a 12-month intervention plus 6-month follow-up, during which time participants could continue to use ET if desired. The intervention period ended in November 2016.

Participants were adults ≥65 who met at least one of these risk factors in the preceding 12 months: (a) one or more falls, (b) receipt of home health services, (c) skilled nursing facility stay, (d) emergency room visit, (e) hospital admission, and (f) sustained sadness or depression. In our original protocol, we specified three of the first five risk factors, but during pilot testing, this proved too restrictive; as a result, to achieve a sufficient sample, only one factor was required when recruitment for the RCT began. We excluded those living in (a) hospice centers, (b) nursing homes, or (c) assisted living without stove access, as well as those (d) needing bed or chair assistance.

We targeted a final sample of 300 (150 per group) after dropouts to provide minimum power (.80 at P<.05) to detect a modest effect size (Cohen’s d≥.4) with an 80% response rate, based on studies of other online interventions we have developed.19,20,21,22 The trial protocol and statistical plan were previously published.23

Ethics

This study, including protocol changes, was approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s social/behavioral science institutional review board (IRB). We do not report 18-month data, owing to sharply reduced sample for follow-up. After 12-month data collection, some team researchers formed a company to market a smartphone application focused on drug addiction. Although the populations using ET versus the recovery app were different, IRB determined that participants should be re-consented, resulting in a decline in participation.

Intervention

Participants randomized to the intervention received ElderTree for 12 months. ElderTree evolved from related online interventions developed at the Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies (CHESS) for various illnesses (e.g., cancer, HIV, asthma, addiction) and tested in randomized trials.19,20,21,22,24

Rapid cycle testing during the design phase allowed us to determine which potential services were most promising and feasible for ET. The interface and services were developed in collaboration with over 300 older adults. As described elsewhere,23,25 we worked with state-funded Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs) in our three areas using the Asset-Based Community Development26 process to understand the resources and challenges of each community. Community volunteers interviewed older adults individually and in groups, conducting tests of paper prototypes and on-screen iterations of the technology to gauge usability. This process resulted in an interactive website offering informational, social, self-management, and motivational services aimed at improving QOL. (See Fig. 2 for the home page and Table 1 for feature descriptions.)

Procedures and Randomization

Participants were recruited by grant-funded coordinators, one for each area, who reached out to older adults through presentations at health fairs, senior centers, churches, and other community venues, as well as each area’s ADRC. After attending presentations, 871 older adults completed a form expressing interest and were assessed for eligibility. Coordinators mailed baseline surveys to those eligible and made home visits to go through the IRB-approved consent form, answer questions, and obtain written consent. During the visit, coordinators collected baseline surveys and described the condition to which the participant was randomized. Other researchers visited to give participants a computer and internet as needed (both conditions) and to train them in the use of ET (experimental condition).

A computer-generated random allocation sequence was used to randomize eligible participants in a 1:1 ratio to ET or control. Randomization was stratified by region (urban, suburban, rural), computer ownership (yes, no), and living status (alone, not alone); used random blocks of sizes 4 and 6; and was implemented by the project director using sequentially numbered sealed envelopes. The sequence was unknown to the onsite coordinators. Researchers who enrolled participants were blind to the envelope’s contents until after consent was given.

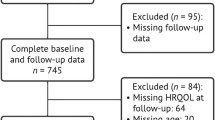

Of 871 older adults assessed for eligibility, 390 agreed to participate, completed baseline surveys, and were randomized to study arm. After randomization, 1 was deemed ineligible, leaving 197 ET and 192 control participants. Of these, 351 (90.0%) completed 6-month surveys (174 ET, 177 control) and 310 (79.5%) completed 12-month surveys (159 ET, 151 control). To retain as many subjects as possible, the 12-month survey included 6 participants who completed baseline but not 6-month surveys (Fig. 3).

Table 2 shows age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, living arrangement, comfort with technology, geographic region, and baseline outcome metrics of the 390 participants.

Measures

Outcome and other measures were gauged at baseline, 6, and 12 months in paper surveys. After completing surveys, participants mailed them to the project director. Validated scales, described below, were used, with minor adaptations of questions to avoid redundancy, reduce burden, and increase readability. Cronbach’s alpha, reported for each scale, is a measure of reliability; higher values indicate greater reliability.

Mental and physical QOL were measured using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health scale.27 Its 10 items subjectively assess physical and mental function, pain, fatigue, social satisfaction, role functioning, depression, and anxiety (Cronbach’s α: baseline=0.88; 6 months=0.86; 12 months=0.87).

Independence was assessed with a 6-item modified Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) checklist.28 Participants reported how easily they could, for example, get to places outside the home, take medications, and deal with finances. Scores were averaged (Cronbach’s α: baseline=0.76; 6 months=0.73; 12 months=0.71).

Social support, received and provided, was measured with 22 items (averaged) based on the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey.29 Items assessed the frequency of positive social interaction, and giving and receiving of informational, emotional, affectionate, and tangible support (Cronbach’s α: baseline=0.95; 6 months=0.96; 12 months=0.96).

Depression was measured with the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (items averaged).30 Respondents indicated whether they, for example, had little interest in doing things; felt down, depressed, or hopeless; and had trouble sleeping (Cronbach’s α: baseline=0.87; 6 months=0.85; 12 months=0.87).

Falls prevention was measured with a modified Falls Behavioral Scale for the Older Person31,32; 15 items assessed the frequency of cognitive and protective adaptations, avoidance of risks, and attention when moving (Cronbach’s α: baseline=0.62; 6 months=0.56; 12 months=0.54).

The use of health services was measured with a modified Medical Services Utilization Form.33 For the last 6 months, participants estimated the number of visits made to their primary care clinic, emergency room, and urgent care, and reported overnight stays in hospital or long-term care (e.g., assisted living facility, nursing home).

ET use data were continuously collected in time-stamped log files, including logon, services used, duration, pages viewed, messages posted and received, weekly surveys completed, and responses to survey items. Future papers will examine system use and weekly survey responses within the current study.

Statistical Analyses

We hypothesized greater improvement over time for the ET group (vs. control) in QOL, social support, falls prevention, independence, and depression. Predictions were tested using cumulative link mixed models (CLMMs) for each outcome across the three time points (baseline, 6, 12 months). Like other mixed models, CLMMs allow some parameters in the model to be treated as random effects and can account for the use of repeated measures from the same respondents.34 CLMMs offer several advantages over linear mixed models: They allow us to analyze ordinal responses without assuming response options are equally spaced or assigned cardinal values. They allow us to model individual responses accounting for their discrete bounded nature. Finally, this type of analysis resembles the intention to treat in that it retains participants who have incomplete data.

For each outcome separately, CLMM models were fit using the “clmm()” function from the ordinal package in R.35 Random effects of intercept and slope for each participant over time were entered with the addition of random effects of the item. We used a CLMM with a logit link, also known as a proportional odds mixed model. Predictor variables were time and study arm. Time was coded as a binary indicator for 6- and 12-month outcomes (time=1) compared to baseline (time=0). Models include an interaction between time and treatment variables as well as main effects. Under this setup, the magnitude of treatment effects is assumed to be constant over time, after baseline. Age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, living arrangement, geographic region, and comfort with technology were entered as covariates in each model.

Moderation analyses examined whether effects differed by age, sex, number of risk factors at baseline, ER and urgent care use, overnight stays in hospital or long-term care, and number of primary care (PC) visits in the 6 months before baseline. Since the moderating effects of PC visits are unlikely to be the same when increasing from 0 to 1 visit versus, for example, 10 to 11 visits or even 2 to 3, we used the Freeman-Tukey transformation on the number of visits. This transformation can be used for count data as it is variance-stabilizing for a Poisson distribution.36 These three-way interaction analyses (time × study arm × moderator) were run using the techniques described above for the main (time × study arm) analyses.

To understand the interactions between time, study arm, and PC visits in the pre-baseline 6 months, number of visits was grouped into terciles using the “interactions” package for R37: 0–1 visit (lower tercile: ET n=98, control n=93), 2 visits (middle tercile: ET n=43, control n=45), and 3+ (max=24) visits (upper tercile: ET n=53, control n=54). Three ET and 2 control participants did not report PC visits.

Role of the Funding Source

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data; preparation, review, approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Contrary to prediction, we did not find a greater improvement over time in any outcome for participants who used ElderTree compared to those who did not. Table 3 presents the results of the main analyses, including both unadjusted P values and type 1 error adjustments.38 (The ElderTree and control groups’ covariate-adjusted scores on outcome measures at baseline, 6, and 12 months are reported in Table 4; see Appendix 1 for detailed results for each outcome.) Given the lack of study arm effects, we did not test for mediation by self-determination theory constructs.

We then examined moderation. We did not find moderation by age, sex, or our health indicators—with the exception of primary care use. As shown in the bottom half of Table 3, among participants with high levels of primary care use (3+ visits) before the study, those in the ET arm (vs. control) showed greater improvements in mental QOL, social support provided and received, and depression (although the P value changed from 0.034 to 0.060 with the more conservative adjustment for multiple tests, as shown in Table 3). A trend toward greater independence is also suggested.

Specifically, as shown in Figure 4, ET participants with the most (3+) primary care visits were 6.4% more likely than control participants with 3+ visits to report “very good” or better mental QOL, while ET participants with the fewest visits (0–1) were 3.1% less likely than control participants with 0–1 visit to do so. High-use ET participants were 6.2% more likely than their control counterparts to report “often” providing social support to others, while low-use ET participants were 5.8% less likely than low-use control participants to do so. High-use ET participants were 5.8% more likely than high-use controls to report “often” receiving social support from others; low-use ET participants were 1.3% less likely than low-use controls to do so. And finally, high-use ET participants were 3.9% more likely than controls to report no depression, while low-use ET participants were 4.4% less likely than controls to do so. Detailed results for all outcomes are provided in Appendix 2.

Probability of ElderTree vs. control participants, by number of primary care visits, responding "very good" or better, "often" or better, and "none at all" on measures of mental quality of life, social support, and depression, respectively (higher probabilities represent better outcomes over time; shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals)

Post Hoc Supplemental Analysis

Results of moderation analyses regarding high levels of primary care use raised the possibility that patients struggling with chronic health conditions were benefiting most from ET. To explore this, we conducted Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis, using a checklist of conditions administered midway through data collection, on mental QOL, social support provided and received, and depression. CART has been increasingly used in public health research to identify target populations 39,40. This analysis indicated that for mental QOL, social support received, and depression, beneficial effects of ET centered on participants with multiple chronic conditions versus one or no condition. For methodological details and the full CART analysis, see Appendix 3.

DISCUSSION

In our study, the ElderTree eHealth system had no overall impact on quality of life or related outcomes for older adults with mild to moderate health challenges who were living in their homes. However, among participants with high levels of primary care use before the study, those assigned to ET showed more positive trajectories for mental quality of life, social support received and provided, and depression.

Our eligibility criteria, focused on health crises in the year prior to recruitment, were less stringent than originally planned. However, we did not find that participants who met more of those criteria benefited more from ET, suggesting that our initial assessment of relevant factors was wrong. The primary care moderation analyses and the post hoc CART analyses suggest that we might do better to focus on patients with chronic conditions rather than those who may have had a health crisis but recovered. We are currently conducting a second RCT to assess whether ET improves psychosocial and health outcomes among patients with multiple chronic conditions.41

According to the latest available data, 94% of Medicare spending is for patients with multiple chronic conditions.42 Treatment of chronic conditions generally occurs in primary care, with a focus on medication and lab results1,6,43,44 but limited time to discuss strategies for self-management or psychological well-being—although such strategies are vital.15 Interventions such as ET that monitor clinical signs, help with self-management of chronic conditions, offer education and motivation tools, and provide social and psychological support may play an increasing role going forward,45,46 especially as adoption rates increase among older adults.47 This seems all the more likely in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which advanced the role of telehealth in easing stress on the healthcare system.45,46

Limitations

Although research staff who consented participants were blind to the condition, there was no meaningful way to blind participants once they were randomized (unlike in a drug trial). Despite this limitation, we reduced bias by giving all participants a laptop and internet access, and by having all participants complete the same measures using paper surveys. An additional limitation is that the survey responses are subject to memory biases. Our ET study currently in progress is using EHRs to verify self-reports.41

Conclusions

While no overall effect was found for our community-based population of older adults using ET, moderation analyses suggest the system might offer psychosocial benefits to patients using high levels of primary care, a healthcare use pattern linked to chronic conditions. Additional research based on these preliminary findings is underway.

References

Molzahn A, Skevington SM, Kalfoss M, et al. The importance of facets of quality of life to older adults: an international investigation. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(2):293-8.

Fassino S, Leombruni P, Abbate Daga G, et al. Quality of life in dependent older adults living at home. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35(1):9-20.

Ekwall AK, Sivberg B, Hallberg IR. Loneliness as a predictor of quality of life among older caregivers. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(1):23-32.

Jakobsson U, Hallberg IR. Pain and quality of life among older people with rheumatoid arthritis and/or osteoarthritis: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(4):430-43.

Salaffi F, Carotti M, Stancati A, et al. Health-related quality of life in older adults with symptomatic hip and knee osteoarthritis: a comparison with matched healthy controls. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17(4):255-63.

Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, et al. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: a time trade off study. BMJ. 2000;320(7231):341-6.

Greenberg S, Administration on Aging (AoA). A profile of older Americans: 2008. Washington, DC: Administration on Aging, U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services; 2008.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). Healthy People 2020: older adults. Accessed at Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/older-adults on August 26, 2020.

Arthritis Foundation. Arthritis pain management. https://www.arthritis.org/living-with-arthritis/pain-management/. .

Macea DD, Gajos K, Daglia Calil YA, Fregni F. The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2010;11(10):917-29.

Bickmore TW, Silliman RA, Nelson K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an automated exercise coach for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1676-83.

King AC, Bickmore TW, Campero MI, et al. Employing virtual advisors in preventive care for underserved communities: results from the COMPASS study. J Health Commun. 2013;18(12):1449-64.

Gray J, O’Malley P. Review: E-health interventions improve blood pressure level and control in hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(12):Jc68.

Cotten SR, Anderson WA, McCullough BM. Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e39.

Czaja SJ, Boot WR, Charness N, et al. Improving social support for older adults through technology: findings from the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Gerontologist. 2018;58(3):467-77.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-regulation and the problem of human autonomy: does psychology need choice, self-determination, and will? J Pers. 2006;74(6):1557-85.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68-78.

Ryan RM, Patrick H, Deci EL, et al. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: interventions based on self-determination theory. Eur Health Psychol. 2008;10(1):2-5.

Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):566-72.

Gustafson D, Wise M, Bhattacharya A, et al. The effects of combining Web-based eHealth with telephone nurse case management for pediatric asthma control: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e101.

Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):435-45.

Gustafson DH, DuBenske LL, Namkoong K, et al. An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Cancer. 2013;119(9):1744-51.

Gustafson DH Sr, McTavish F, Gustafson DH Jr, et al. The effect of an information and communication technology (ICT) on older adults' quality of life: study protocol for a randomized control trial. Trials. 2015;16(1):191.

Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, et al. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(1):1-9.

Gustafson DH Sr, McTavish F, Gustafson D Jr, et al. The use of asset-based community development in a research project aimed at developing mHealth technologies for older adults. In: Rehg JM, Murphy SA, Kumar S, eds. Mobile health: sensors, analytic methods, and applications. New York: Springer; 2017.

Kretzmann JP, McKnight JL. Building communities from the inside out: a path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Chicago, IL: ACTA Publications; 1993.

Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873-80.

Noelker LS, Browdie R, Katz S. A new paradigm for chronic illness and long-term care. Gerontologist. 2014;54(1):13-20.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705-14.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163-73.

Clemson L, Cumming RG, Heard R. The development of an assessment to evaluate behavioral factors associated with falling. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(4):380-8.

Clemson L, Bundy AC, Cumming RG, et al. Validating the Falls Behavioural (FaB) Scale for older people: a Rasch analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(7):498-06.

Polsky D, Glick HA, Yang J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for opioid-dependent youth: data from a randomized trial. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1616-24.

Hedeker D. Methods for multilevel ordinal data in prevention research. Prev Sci. 2015;16(7):997-1006.

Christensen RH. Ordinal—regression models for ordinal data. R package version 2019.12-10. 2019.

Mosteller F, Youtz C. Tables of the Freeman-Tukey Transformations for the Binomial and Poisson distributions. Biometrika. 1961;48(3/4): 433-40. . doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2332765.

Long J. Interactions: comprehensive userfriendly toolkit for probing interactions (Version 1.0). 2019.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological). 1995; 57(1): 289-300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Lemon SC, Roy J, Clark MA, et al. Classification and regression tree analysis in public health: methodological review and comparison with logistic regression. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(3):172-81.

Speybroeck N. Classification and regression trees. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(1):243-6.

Gustafson Sr D, Mares M, Johnston D, et al. A web-based eHealth intervention to improve the quality of life of older adults with multiple chronic conditions: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2021;10(2):e25175. doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/25175.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS.gov). Chronic conditions/ Chartbooks and charts/ Chronic conditions charts: 2017 (ZIP), slide 13. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/Chartbook_Charts. .

Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an aging America: building the health care workforce. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2008.

Farber N, Shinkle D, Lynott J, et al. Aging in place: a state survey of livability policies and practices. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. June 10, 2020. Accessed at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html on August 26, 2020.

Lin LA, Fernandez AC, Bonar EE. Telehealth for substance-using populations in the age of Coronavirus Disease 2019: recommendations to enhance adoption. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020. Epub July 2, 2020.

Pew Research Center. Tech Adoption Climbs Among Older Adults. May 17, 2017. Accessed at Pew research Center Internet & Technology, at https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/ on October 27, 2020.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Asset-Based Community Development leadership, the project staff who recruited subjects and maintained relationships in our three geographic regions, the hundreds of older adults who guided this work and participated in its evaluation, and the researchers who worked with them.

Funding

This project was supported by grant number P50HS019917 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

David H. Gustafson Sr. has a small shareholder interest in CHESS Health, a corporation that develops healthcare technology for patients and family members struggling with addiction; this relationship is managed by Dr. Gustafson and the UW–Madison’s Conflict of Interest Committee. No other disclosures are reported.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 142 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gustafson, D.H., Kornfield, R., Mares, ML. et al. Effect of an eHealth intervention on older adults’ quality of life and health-related outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 521–530 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06888-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06888-1