Abstract

BACKGROUND

It is well established that specialists often adopt new medical technologies earlier than generalists, and that racial and ethnic minority patients are less likely than White patients to receive many procedures and prescription drugs. However, little is known about the role that specialists or generalists may play in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in uptake of new medical technologies. Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA tests, introduced as a cervical cancer screening tool in 2000, present a rich context for exploring patterns of use across patient and provider subgroups.

OBJECTIVE

To identify patient characteristics and the provider specialty associated with overall and appropriate use of HPV DNA tests over time, and to examine the associations between clinical guidelines and adoption of the test in an underserved population.

DESIGN

Retrospective longitudinal study using Florida Medicaid administrative claims data.

PARTICIPANTS

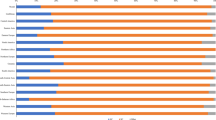

Cervical cancer screening test claims for 415,239 female beneficiaries ages 21 to 64 from July 2001 through June 2006.

MAIN MEASURES

Overall and appropriate use of HPV DNA tests.

KEY RESULTS

Although minority women were initially less likely than White women to receive HPV DNA tests, test use grew more rapidly among Black and Hispanic women compared to White women. Obstetricians/gynecologists were significantly more likely than primary care providers to administer HPV DNA tests. Release of the first set of clinical guidelines was associated with a large increase in the use of HPV DNA tests (adjusted odds ratio: 2.46, p < 0.0001); subsequent guidelines were associated with more modest increases.

CONCLUSIONS

Uptake of new cervical cancer screening protocols can occur quickly among traditionally underserved groups and may be aided by early adoption by specialists.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Harrold LR, Field TS, Gurwitz JH. Knowledge, patterns of care, and outcomes of care for generalists and specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(8):499–511.

De Smet BD, et al. Over and under-utilization of cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors by primary care physicians and specialists: the tortoise and the hare revisited. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):694–7.

Hirth RA, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME. Specialist and generalist physicians' adoption of antibiotic therapy to eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection. Med Care. 1996;34(12):1199–204.

Landon BE, et al. Physician specialization and antiretroviral therapy for HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(4):233–41.

Rappaport KM, Forrest CB, Holtzman NA. Adoption of liquid-based cervical cancer screening tests by family physicians and gynecologists. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):927–47.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Disparities Report. 2008 [cited; Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr08/nhdr08.pdf. Accessed May 2010.

Jha AK, et al. Racial trends in the use of major procedures among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):683–91.

Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, D.C.; 2003.

Epstein AM, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation-clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med. 2000;343(21):1537–44. 2 p preceding 1537.

Schneider EC, et al. Racial differences in cardiac revascularization rates: does "overuse" explain higher rates among white patients? Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):328–37.

Canto JG, et al. Relation of race and sex to the use of reperfusion therapy in Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(15):1094–100.

Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ. Racial disparities in medical care. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1471–3.

Sirovich BE, Welch HG. The frequency of Pap smear screening in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):243–50.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA; 2004.

National Council on Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality. Washington, DC; 2006.

Adams EK, Breen N, Joski PJ. Impact of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program on mammography and Pap test utilization among white, Hispanic, and African American women: 1996–2000. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):348–58.

Hewitt M, Devesa SS, Breen N. Cervical cancer screening among US women: analyses of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med. 2004;39(2):270–8.

Lewis BG, et al. Preventive services use among women seen by gynecologists, general medical physicians, or both. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):945–52.

US Food and Drug Administration. Approval order for Digene Hybrid Capture® 2 (HC2)High-Risk HPV DNA Test - P890064/S009 2003 [cited July 13, 2006]; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/pdf/p890064s009a.pdf. Accessed May 2010

Wright TC Jr, et al. Interim guidance for the use of human papillomavirus DNA testing as an adjunct to cervical cytology for screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):304–9.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 3rd ed. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003.

Wright TC Jr, et al. 2001 Consensus Guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2120–9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 45, August 2003. Cervical cytology screening (replaces committee opinion 152, March 1995). Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(2):417–27.

Saslow D, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):342–62.

Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus DNA testing and HPV-16, 18 vaccination. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(5):308–20.

Freeman, H., Wingrove, B. Excess cervical cancer mortality: A marker for low access to health care in poor communities. May 2005, National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities: Rockville, MD.

Saraiya M, et al. Cervical cancer incidence in a prevaccine era in the United States, 1998–2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):360–70.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Conversion Table of New ICD-9-CM Codes. October 2009 [cited; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd9/icdcnv10.pdf. Accessed May 2010.

Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2003. 188(6): p. 1383–92.

Fitzmaurice, G., Laird, N., Ware, J. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. 2004, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Williams R. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56:645–646.

Irwin K, et al. Cervical cancer screening, abnormal cytology management, and counseling practices in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):397–409.

Saraiya M, et al. Cervical cancer screening and management practices among providers in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP). Cancer. 2007;110(5):1024–32.

Noller KL, et al. Cervical cytology screening practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(2):259–65.

Jain N, et al. Use of DNA tests for human Papillomavirus infection by US clinicians, 2004. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(1):76–81.

Institute of Medicine. Chapter 2. Definitions and key terms, in Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. In: L.K. Field MJ, Editor. 1990, National Academy Press: Washington, DC.

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157(4):408–16.

Cabana MD, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65.

Feder G, et al. Clinical guidelines: using clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7185):728–30.

Grimshaw J, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S14–20.

O'Malley AS, Pham HH, Reschovsky JD. Predictors of the growing influence of clinical practice guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):742–8.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges Paul Cleary, Richard Frank, and Sue Goldie for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript, and Christina Fu for outstanding technical assistance. The author was supported, in part, by a George Bennett Fellowship from the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making.

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract no. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Use of HPV DNA Testing, 2002–2004

Consensus Guidelines from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (April 2002)22 | American Cancer Society Guidelines (November 2002)24 | United States Preventive Services Task Force Guidelines (January 2003)21 | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Guidelines (August 2003)23 | Co-sponsored Interim Guidance from National Cancer Institute, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and American Cancer Society (February 2004)20 | |

HPV DNA testing for triage of ASC-US Pap test results | Yes | Not addressed | Not addressed | Yes | Yes |

HPV DNA testing in conjunction with Pap test for primary screening in women age 30+ | Not addressed | It would be reasonable to consider that for women aged 30 or over screening may be performed every 3 years using cytology combined with a test for high-risk HPV types | Insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for HPV infection | Once a woman reaches age 30, it is appropriate for her to have the test for the HPV at the same time as the Pap | HPV DNA testing may be added to cervical cytology for screening in women aged 30 years and older |

Procedure Codes

Claim | Procedure codes |

HPV DNA testing | 87620, 87621, 87622 |

Thin preparation Pap testing | 88142, 88143, 88174, 88175 |

Conventional Pap testing | 88141,88144, 88145, 88147, 88148, 88150-5, 88160-2, 88164-7 |

Colposcopy | 57452, 57454 |

Clinical visit | 99201-5, 99211-5, 99241-5, 99385-6, 99395-6 |

Hysterectomy | 58150, 58152, 58200, 58210, 58240, 58260, 58262-3, 58267, 58270, 58275, 58280, 58285 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anhang Price, R. Association Between Physician Specialty and Uptake of New Medical Technologies: HPV Tests in Florida Medicaid. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 1178–1185 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1415-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1415-9