Abstract

Research on educational inequalities has increasingly focused on interventions to increase enrollment in higher education for students of low social origin. However, students of low social origin may not be homogeneous in their need for advice, as natives of low social origin decide less frequently to enter university than their immigrant counterparts in many European countries. Drawing on data from a randomized controlled trial in German schools, we find that counseling in particular does indeed increase the likelihood of enrollment for native students. We then use the results of our empirical analyses to illustrate how an upscaling across schools would affect migration-specific enrollment rates of students of low social origin at the aggregate level. We discuss the implications of our results for research on migration-related inequalities in enrollment as well as for policy regarding program upscaling.

Zusammenfassung

Die Forschung zu Bildungsungleichheiten hat zunehmend Maßnahmen in den Blick genommen, die darauf zielen, die Studienaufnahme von Personen niedriger sozialer Herkunft zu erhöhen. Schülerinnen und Schüler niedriger sozialer Herkunft könnten jedoch bezüglich ihres Beratungsbedarfs nicht homogen sein, da in vielen europäischen Ländern Studienberechtigte ohne Migrationshintergrund niedriger sozialer Herkunft seltener ein Studium beginnen als diejenigen mit Migrationshintergrund gleicher sozialer Herkunft. Unsere empirischen Ergebnisse, die auf Daten einer randomisiert kontrollierten Studie an deutschen Schulen basieren, legen nahe, dass eine individuelle Beratung tatsächlich vor allem die Studienaufnahme von Studienberechtigten ohne Migrationshintergrund erhöht. Anschließend nutzen wir die Ergebnisse unserer empirischen Analysen, um zu illustrieren, wie sich eine Ausweitung des Programms über Schulen hinweg auf die aggregierten Studienaufnahmequoten von Studienberechtigten niedriger sozialer Herkunft mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund auswirken würde. Wir diskutieren die Implikationen unserer Ergebnisse für die Forschung zu migrationsbezogenen Ungleichheiten in der Studienaufnahme sowie politische Implikationen in Bezug auf die Ausweitung von Programmen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the past decade, politicians, practitioners, and researchers have been increasingly interested in policies and programs aimed at reducing educational inequality in general (see Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung [BMBF] 2019; DiPrete and Fox-Williams 2021, p. 17 ff.) and with respect to higher education in particular (BMBF 2010, pp. 51, 56; for a review, see Herbaut and Geven 2020). Among other mechanisms, encouragement and information have been considered instruments for increasing the participation of students from less privileged backgrounds in more advanced education pathways, including higher education (e.g., Barone et al. 2017; Belasco 2013; Ehlert et al. 2017; Keller et al. 2022; Peter and Zambre 2017; Robinson and Roksa 2016; Sattin-Bajaj et al. 2018). In particular, guidance counselors have a considerable impact on the enrollment of students of low social origin (for a review: Herbaut and Geven 2020).

Although research in the USA has raised the issue that educational programs, including guidance counseling, may affect racial or immigration-specific disparities in educational success at different educational stages (see Castleman et al. 2015; See et al. 2012), the impact of counseling as such, and in particular, on immigration-specific inequalities in enrollment has not been thoroughly investigated in Europe. However, looking at students with and without immigrant backgrounds among those of low social origin may be particularly constructive, as in Germany (and in many European countries), immigrants who are entitled to enroll in higher education actually do so more frequently than their native counterparts of equal social origin and performance level (e.g., Kristen et al. 2008; Kristen 2016, p. 650; Mentges 2019; Sudheimer and Buchholz 2021; for Europe: Griga and Hadjar 2014). This finding is often (partially) explained by immigrant students’ higher aspirations (e.g., Becker and Gresch 2016; Salikutluk 2016; Neumeyer et al. 2022) and their strong motive for intergenerational upward mobility (“immigration optimism”; Kao and Tienda 1995; Vallet 2006; see Relikowski et al. 2012). Hence, students of low social origin are not homogeneous as a group, and native students might benefit more strongly from motivational advice in their pursuit of higher education than immigrants of equal social origins. Consequently, a perspective on the impact of counseling that differentiates between natives and immigrants among students of low social origin may contribute to a better understanding of how enrollment can be encouraged, particularly for natives of low social origin who have been overlooked in previous research on educational inequalities.

Although sociologists are keen to understand educational inequalities at the aggregate level and make an effort to model how different policies and interventions would affect disparities (see Lundberg 2022; Jackson and Cox 2013, p. 41), to date, many studies on educational interventions have only reported (heterogeneous) treatment effects and mentioned potential macro-level implications in the concluding section. To evaluate the impact of counseling programs on enrollment rates group-specific participation rates also have to be taken into account (Pietrzyk and Erdmann 2020). First, the size of the treatment effect matters, as a positive effect suggests that enrollment might increase. Second, as counseling is typically voluntary, the number of individuals participating in such programs if given the opportunity is crucial for aggregate enrollment rates (take-up rate). Finally, the extent of implementation of the program plays a role, as upscaling of a program leads to a larger number of students being reached by the program, which impacts aggregate enrollment rates.

Against this backdrop, we investigate (1) whether guidance counseling affects the enrollment in higher education of natives and immigrants of low social origin, (2) which mechanisms drive its effects, particularly regarding the motive for intergenerational upward mobility, and (3) to what extent it reduces inequality in enrollment rates by immigrant status among persons of low social origin. To investigate these questions, we use a unique data set from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on a counseling program of upper secondary school students.

This study contributes to previous research in the following respects:

(1) Against the backdrop of the phenomenon of higher enrollment of immigrants compared with natives observed in several European countries, we focus on native students of low social origin who might be particularly in need of motivational advice on their way to higher education.

(2) By addressing various rational choice components as potential mechanisms of the effect, i.e., the motive for upward mobility, costs, and the probability of the successful completion of university, we contribute to theoretical considerations on immigration-specific educational choices.

(3) Although previous research on the impact of educational interventions typically ends with an estimation of the effect on enrollment, we go beyond the micro level. Using our empirical results on the treatment effect and take-up rates, we examine enrollment rates of natives and immigrants of low social origin based on different levels of upscaling of the program across schools. Thus, we illustrate how conclusions at the aggregate level can be systematically drawn from experimental micro data.

2 Background

2.1 Why do Native Students of Low Social Origin Benefit from Counseling?

Students of low social origin are less likely to enroll in higher education than students from high social origins in many Western countries (Shavit et al. 2007). Researchers have traced this disadvantage for students of low social origin to the so-called primary and secondary effects of social origin, which denote differences between social classes concerning their academic performance and their evaluation of the benefits, costs, and subjective probability of successful completion (Boudon 1974; Breen and Goldthorpe 1997; Erikson and Jonsson 1996). Researchers in the field of educational inequality have thoroughly investigated how programs that provide information and support affect enrollment (for an overview, see Herbaut and Geven 2020) and with respect to social origin in particular (e.g., Barone et al. 2017; Ehlert et al. 2017; Erdmann et al. 2022). Among the different programs, guidance counseling has been shown to be the most effective in raising the university access for students of low social origin (Herbaut and Geven 2020, p. 5 f.).

Sociological research in the USA and the UK has also been concerned with how specific programs mitigate racial or immigration-specific educational disparities (e.g., Gast 2022; See et al. 2012). To date, in Europe, research on immigration-specific disparities in higher education enrollment has not been systematically integrated into this strand of research even though immigration-specific disparities exist. More specifically, immigrants who are entitled to enroll in higher education do so more frequently than their native peers of equal social origin. This pattern was found, for example, in France (Brinbaum and Guégnard 2013), Germany (Kristen et al. 2008; Kristen 2016; Mentges 2019; Dollmann and Weißmann, 2020; Sudheimer and Buchholz 2021; Busse and Scharenberg 2022; but see: Lörz 2019), Norway (Fekjær and Birkelund 2007), Sweden and England (Jackson et al. 2012), and Switzerland (Griga 2014) as well as in an analysis using European data (Griga and Hadjar 2014). As the more ambitious educational choices of immigrants in some countries are revealed only after consideration of the academic performance level, researchers termed this empirical pattern the immigration-specific secondary effect (Heath and Brinbaum 2007, p. 297 f.).

Studies mainly support that so-called immigration optimism (Kao and Tienda 1995; Vallet 2006) is the driving force behind the more ambitious educational choices of immigrants (Dollmann 2017, 2021; Salikutluk 2016; Tjaden and Hunkler 2017). Although generally, persons are assumed to only aspire to maintain their parents’ social status (Boudon 1974), immigrants’ objectives differ from that general pattern (Heath et al. 2008, p. 223). That is, immigrants are more oriented toward intergenerational upward mobility than natives, which translates into their highly ambitious educational choices. This strong motive for upward mobility presumably goes back to immigrants’ positive selection. As emigration involves the high costs of leaving the familiar social environment behind, particularly persons with a strong motive for upward mobility may decide to leave their country of origin voluntarily. Yet, the expectation of higher prosperity often does not come true owing to challenges and barriers. Against this backdrop, the notion forms within immigrant families that their children may attain superior socio-economic status by excelling in education (see Kao and Tienda 1995; Vallet 2006, p. 142).

The ambitious educational choices of immigrants have generally been described as advantageous for immigrants compared with natives (e.g., Dollmann 2017; Engzell 2019; Heath et al. 2008; Jackson et al. 2012; Kristen et al. 2008; Klein and Neugebauer 2023). This perspective can be traced to researchers typically analyzing how immigrants’ educational choices deviate from natives’ choices, thereby implicitly categorizing immigrants as a deviation from the native norm. The reverse perspective that natives make less ambitious educational choices than immigrants, which is disadvantageous for natives, has rarely been adopted by researchers. However, this perspective is also valid and, more importantly, it stimulates research in the field of educational programs that addresses (any) group-specific disadvantages.

Building on rational choice theories and the native disadvantage in university access, we derive three hypotheses. Students of low social origin face barriers with regard to costs and probability of success. Professional advice may break these barriers down by, for example, providing information on financing options and academic requirements. As a result, we expect counseling to have a positive effect on enrollment for students of low social origin (H 1). However, these students may not be homogeneous regarding how strongly they are pulled toward higher education. Immigrants of low social origin are known to lean more toward enrollment than natives do—owing to their comparatively ambitious goals. As counseling may encourage students to develop such goals, we expect that natives of low social origin strongly benefit from counseling and that they benefit more strongly than immigrants of low social origin (H 2). Accordingly, we assume that counseling reduces the perception of barriers to higher education (costs and success probability) equally among natives and immigrants of low social origin, whereas it strengthens the motive for upward mobility, particularly among natives (H 3).

2.2 How Does Counseling of Natives and Immigrants Translate into (In-)equality in Enrollment Rates?

Regarding the potential of an intervention to mitigate inequality, recent studies have pointed out that in addition to the program effect of different social groups (i.e., treatment effect), group-specific participation rates matter for (in-)equality in aggregate enrollment rates (Pietrzyk and Erdmann 2020). The latter reflects the proportion of students participating in the program if given the opportunity (take-up rates). The opportunity of participation depends, in turn, on the level of implementation of the program, e.g., across schools, which we call the level of “upscaling” of the program.

Against this backdrop, using estimates of group-specific treatment effects and take-up rates gained through our experimental design, we illustrate how counseling would reduce inequality at the population level based on immigrant status among persons of low social origin, depending on different levels of upscaling.

3 Research Design

3.1 The Counseling Program

We investigated the research questions in the context of a guidance counseling program run by universities and universities of applied sciences in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The core of the program is individual, intensive student counseling in a upper secondary school by specifically qualified counselors from university advisory services. The program’s primary goal at the time of our study was to foster university enrollment among persons of low social origin. Further objectives were, for example, to support students in developing ambitious goals, to help students to develop the self-confidence to realize their educational and professional objectives, to plan concrete actions to realize the goals (see Qualification for Counselors n.d.).

During counseling sessions, counselors advised students in various ways, depending on students’ individual needs, for example, the choice between vocational training and university enrollment, the type of higher education institution, the choice of major, the requirements for applying for university admission or financing one’s studies. As the program was based on student needs, the frequency of counseling sessions varied. In our sample, students participated on average in five counseling sessions. The program is designed to provide long-term support and may continue even after the students leave school. It is currently implemented in around 30% of all upper secondary schools in North Rhine-Westphalia; among schools with socially disadvantaged students, 40% of schools are covered by the program.

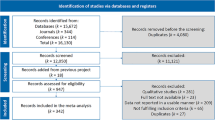

3.2 Data: The Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

The ZuBAb study (“Zukunfts- und Berufspläne vor dem Abitur” [Future and career plans before high school graduation]) was a RCT that evaluated the counseling program outlined above (for an overview, see Pietrzyk et al. 2019).Footnote 1 It was conducted in upper secondary schools in North Rhine-Westphalia in sociostructurally disadvantaged surroundings.Footnote 2 The RCT was carried out in the following steps (Fig. 1). For the baseline measurement, students in 30 schools were surveyed using a standardized instrument. All students who attended the penultimate year before school graduation were targeted. They were asked about their plans for professional life and post-school pathways, their social environment, their interests, and various psychosocial competencies by means of a paper and pencil questionnaire.

Owing to the limited capacity for program delivery of the universities and counselors involved, not all students who participated in the baseline survey could be included in the RCT. Students were selected randomly and individually for RCT participation within schools (N = 1344; among those n = 703 of low social origin, the target group of our analysis). In accordance with the target group of the program, students of low social origin were prioritized, whereas students from high social origins were only included in the RCT if free participation places remained at a given school. Social origin was defined by the parents’ highest educational degree: students without/with a parent who had graduated from a higher education institution were considered of low/high social origin.

Participants in the RCT were then randomly and individually assigned to a treatment condition with program participation and a control condition without program participation. School and social origin served as blocking variables.Footnote 3 Overall, the randomization led to an equal distribution of essential predictors of enrollment between experimental conditions, namely the intention to enroll in university and academic achievement at baseline measurement (see Table A1 in Online Appendix). Furthermore, randomization led to an almost equal distribution of immigrant status among persons of low social origin across experimental conditions (see Table A2 in Online Appendix). The program began immediately after the baseline measurement and random assignment of students to experimental conditions. Therefore, counseling started around 1 year before school graduation for participating students. Compliance with random assignment was about 80% (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix).

In the further course of the study, study participants were surveyed in three additional waves.Footnote 4 Regarding enrollment, we used data gathered 1.5 years after school graduation in wave 4. Our analytical sample is based on RCT participants of low social origin only. Owing to panel attrition and missing data,Footnote 5 the main results are based on N = 559 persons of low social origin, including n = 240 natives (treatment condition: n = 123, control condition: n = 117) and n = 319 immigrants (treatment condition: n = 158, control condition: n = 161).Footnote 6

3.3 Analytical Procedures

3.3.1 Program Effect for Natives and Immigrants

We estimate the local average treatment effect (LATE) by conducting instrumental variable (IV) regressions, with treatment assignment serving as the instrument for actual participation. When estimating the participation effect, this procedure considers both the random assignment and the actual participation in the counseling program. It informs about the impact on those who were induced to participate in the program by random assignment to the treatment condition (see Angrist et al. 1996).

To test the treatment effect on enrollment, we run a model for all persons of low social origin and a model with an interaction term between immigrant status and program participation (with the interaction between immigrant status and treatment assignment being a second instrument). In these models, university enrollment 1.5 years after high school graduation serves as the outcome (wave 4), and we apply robust standard errors.Footnote 7 To check for the robustness of the main results, we run different models. First, we additionally consider academic performance at baseline, as randomization led to a slightly unequal distribution of academic performance across experimental conditions for immigrants. Second, we use the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach, in which only treatment assignment is considered. Third, we conduct analyses with school fixed effects.

To test the treatment effect on the rational choice components, we also run IV regressions with an interaction term between immigrant status and program participation (with the interaction between immigrant status and treatment assignment being a second instrument). In these models, the motive for upward mobility and the perceived costs and success probability measured during the last year before high school graduation (wave 2) serve as the outcomes, and we apply robust standard errors.

3.3.2 Program Effect on the Aggregate Level

Group-specific estimations of LATE are not sufficient to conclude how a program influences enrollment rates at the aggregate level. Specifically, Pietrzyk and Erdmann (2020) pointed out that the extent to which programs reduce educational inequality at the aggregate level depends on the treatment effect for different social groups (LATEj) and group-specific participation rates (PRj).

Hence, the enrollment rate of group j denoted by \({\overline{Y}}_{\mathrm{agg}}^{j}\) is calculated by

with the enrollment rate without treatment (\(\overline{Y}^{j0}\)) modified by the local average treatment effect (LATEj) weighted by the participation rate of the group j (PRj), and \(\overline{Y}^{j0}\) weighted by the share of non-participants (1−PRj).

The participation rate of group j PRj is determined by the take-up rate (TUj) and the extent of implementation, that is, upscaling (US), as follows:

Inserting Eq. 2 into Eq. 1 and simplifying, we obtain the following prediction of \({\overline{Y}}_{\mathrm{agg}}^{j}\):

This equation allows us to calculate whether and in which respect the extent of implementation of the program across schools would affect group-specific enrollment rates.

For \(\overline{Y}^{j0}\), LATEj, and TUj, we use our empirical results.Footnote 8 Specifically, \(\overline{Y}^{j0}\) is the predicted enrollment rate for non-participants and LATEj the group-specific local average treatment effect. TUj is the compliance rate to the treatment assignment.Footnote 9 For simplicity, we apply only one value of US for both natives and immigrants, thereby assuming that upscaling is equally distributed across schools with a low and a high proportion of immigrants.

3.4 Operationalization

Immigrant Status. Immigrant status is measured by the country of birth of respondents, their parents, and their grandparents. When the respondent, at least one parent, or at least two grandparents were born abroad, the respondent is assumed to be an immigrant; otherwise, the respondent is a native.Footnote 10 This rather broad conceptualization is based on the operationalization of immigrant status in the National Educational Panel Study (Olczyk et al. 2014). It is reasonable in the German context as labor market recruitment started in the late 1950s in Germany, leading to the descendants of former so-called guest workers living in the third generation in Germany. For reasons of simplicity, we speak of “immigrants” rather than “descendants of immigrants” in the following.

Enrollment. We operationalize enrollment by whether the respondent was enrolled at a higher education institution 1.5 years after leaving upper secondary school, regardless of the type of institution, for example, university or university of applied sciences.

Motive for upward mobility: This motive is measured on a five-point Likert scale with the question “How important is it for you to achieve a higher income than your father in your later professional life?”.

Costs. The perception of costs is measured on a five-point Likert scale with the question “During vocational training or studies, various things have to be paid for, e.g., travel expenses, books, rent, or fees. Regardless of your actual educational aspirations, how much of a financial burden would it be on you and your family to cover these costs if you were to study?”

Success Probability. The perception of success probability is measured on a five-point Likert scale with the question “How likely do you think it is that you could manage to study after finishing school?”.

4 Results

4.1 Do Students of Low Social Origin Benefit from Counseling?

First, we tested whether program participation enhances enrollment of persons of low social origin, regardless of immigrant status. The results of the IV regression model yield a moderate LATE of around 13 percentage points for all persons of low social origin (p < 0.05; see Table B1 in the Online Appendix). Therefore, our results confirm a positive impact of counseling on enrollment among persons of low social origin.

Second, we tested the hypothesis of a particularly strong effect for native students. Indeed, results from an IV regression reveal a strong LATE for natives (see Table B2 in the Online Appendix). More specifically, the effect is estimated to be 22 percentage points for natives (p < 0.05). In contrast, the LATE for immigrants is estimated to be seven percentage points (not statistically significant). Looking at the interaction term between immigrant status and participation, it amounts to −15 percentage points, suggesting a more substantial treatment effect for natives than for immigrants. However, this interaction term does not reach statistical significance.

To illustrate the findings, Fig. 2 shows predicted probabilities of university enrollment for natives and immigrants who did not participate and who did participate in the program. The figure illustrates the difference in LATE between natives and immigrants, as discussed above. Among natives who did not take part in the program, only 5 out of 10 persons enrolled in university (predicted enrollment rate: 49%), whereas around 7 out of 10 persons enrolled in university if they had taken part in the program (predicted enrollment rate: 71%). The difference between immigrants who did not participate and who did participate in the program is much lower (predicted enrollment rate: 58% vs 64%).Footnote 11 Looking at those who did not participate in the program, we see that natives were less likely to enroll than immigrants, reflecting immigrants’ strong educational aspirations without treatment (predicted enrollment rate: 49% vs 58%). For participants, the pattern is reversed, with natives being more likely to enroll than immigrants (71% vs 64%).

Predicted probabilities of enrollment by immigrant status and program participation. (Note: Predicted probabilities are based on an IV regression with random assignment to experimental conditions and the interaction between immigrant status and random assignment serving as instruments (see Table B2 in the Appendix); N = 559 students of low social origin)

4.1.1 Robustness Checks

The finding of a positive treatment effect for natives and a (descriptively) lower effect for immigrants is robust across model specifications. When academic performance at baseline is additionally considered, the native effect is estimated to be 20 percentage points (p < 0.05), whereas the interaction term is estimated to be −22 percentage points and is statistically significant (p < 0.10; see Table C1 in the Online Appendix). The increase in effect heterogeneity after consideration of academic performance may be due to the fact that randomization led to a slightly unequal distribution of academic performance across experimental conditions for immigrants.

The ITT approach provides slightly lower estimates for the native effect (without academic performance: 14, p < 0.05, with academic performance: 12, p < 0.05) and slightly lower estimates of effect heterogeneity than in the IV regressions (without academic performance: −9 percentage points, p > 0.10; with academic performance: −14 percentage points, p < 0.10; see Table C2 in the Online Appendix). The lower estimates when using ITT compared with IV regressions are not surprising against the backdrop of imperfect compliance with random assignment in the investigated sample.

Furthermore, when introducing school fixed effects, IV estimates mainly correspond to the main results. Without consideration of academic performance at baseline, the native effect is 19 percentage points (p < 0.05), and effect heterogeneity based on immigrant status is estimated to be −12 percentage points (p > 0.10). With consideration of academic performance, the native effect is 20 percentage points (p < 0.05) and effect heterogeneity is estimated to be −20 percentage points (p < 0.10; see Table C3). However, as randomization did not lead to an equal distribution of natives and immigrants of low social origin within schools, these estimates may be imprecise.

In addition, we run the main model with a different specification of immigrant status. More specifically, we excluded immigrant students of the third generation from the analysis. The results remain largely stable, as we observe a native effect of 22 percentage points (p < 0.05) and an interaction term of −13 percentage points (p > 0.10; see Table C4) under this specification.

4.2 Does Counseling Influence Rational Choice Components Among Students of Low Social Origin?

We investigated the proposed explanation for the strong treatment effect among natives, that is, whether natives’ upward mobility motive has been strongly enhanced by program participation and whether it has been particularly enhanced when compared with immigrants, whereas the perception of the barriers to enrollment (costs and probability of success) has been equally reduced for both groups.

Looking at immigration-specific differences on the relevant rational choice components before the treatment started (see Table B3 in the Online Appendix) we saw that natives’ motive for upward mobility was weaker than immigrants’ desire for upward mobility—a result that corresponds to prior research and our expectations. Furthermore, we observed no immigration-specific differences in the perception of barriers of enrollment: natives perceived the costs of higher education and their probability of success for higher education in a similar manner to immigrants.

We then tested how program participation has influenced the relevant rational choice parameters. We estimated the LATE on these rational choice components, measured after the program had started in wave 2 (last year before school graduation), based on IV regressions with an interaction term between immigrant status and participation.

Our findings (see Table 1) suggest that natives did not benefit from program participation concerning their motive for upward mobility. For this group, the LATE on the upward mobility motive of −0.149 on a z-standardized scale is descriptively negative, suggesting a negative effect on the motive, but nonsignificant (p > 0.10). Furthermore, the (nonsignificant) interaction coefficient of 0.38 points on a z-standardized scale rather suggests that participation enhanced immigrants’ upward mobility motive more strongly than that of natives (p > 0.10). Contrary to our expectations, it therefore appears that program participation has possibly strengthened the already strongly developed motive for upward mobility of immigrants rather than motivating natives to strive for status gain. Instead, the perceived costs of higher education are reduced for natives and are furthermore heterogeneously affected in favor of natives. More specifically, program participation reduced the perceived costs among natives moderately by 0.42 points on a z-standardized scale (p < 0.05), whereas it did not mitigate the perceived costs among immigrants (interaction term: 0.62 points on a z-standardized scale, p < 0.05). Concerning perceived probability of success, we do not observe an effect of program participation for natives or immigrants.

4.3 How Does Counseling Impact Enrollment Rates of Natives and Immigrants of Low Social Origin?

Based on the strong treatment effect for natives, one could conclude that the program considerably enhances enrollment of natives and thereby reduces differences in the enrollment rates of natives and immigrants. However, such conclusions based solely on the treatment effect may be misleading as, for example, the extent of program implementation affects aggregate enrollment rates of both groups and potential convergence of enrollments. Therefore, we may now look more closely at aggregate enrollment rates and how they may be affected by the extent of upscaling of the program across schools.

We use the results from our estimations to calculate aggregate enrollment rates. Although each of the parameters is prone to change, for our illustrative purposes, we focus on upscaling of the given program and assume that our estimated parameters can be generalized to other schools and that they are unaffected by upscaling. We are well aware of the strong methodological assumptions (discussed, for example, in footnote 8). However, rather than merely speculating about macro-level implications, we extrapolate our findings more systematically than previous research and aim to inspire further research on the aggregation of treatment effects.

Table 2 lists the values that we use to calculate the aggregate enrollment rates. In addition to values gained from the above presented results, we approximate TUj by the compliance rate to treatment assignment, which is the participation of those who had been assigned to the program and who actually took the offer. In our sample, we observed the take-up of natives to be lower than that of immigrants (78% vs 85%).Footnote 12

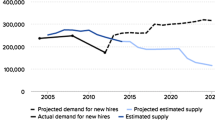

Figure 3 shows that the enrollment rate of natives of low social origin converges with the enrollment rate of immigrants with increasing levels of program upscaling across schools. The steeper slope for natives reflects their stronger LATE compared with immigrants. However, the program benefit for natives is partially counteracted by their lower take-up rate. Considering the gap between the group-specific enrollment rates, an upscaling of the intervention by ten percentage points corresponds to a reduction in the native–immigrant enrollment gap by 1.2 percentage points.Footnote 13 At about 80% school coverage, the enrollment rate of natives catches up with that of immigrants.

If we apply the current extent of the program’s implementation in North Rhine-Westphalia, around 30% of upper secondary schools, the program increased the enrollment rate for natives of low social origin by five percentage points and by two percentage points for immigrants (compared with the pre-implementation phase). Therefore, natives’ enrollment rate has come considerably closer to the enrollment rate of immigrants, thereby reducing the initial immigration-specific enrollment gap of nine percentage points to five percentage points: this corresponds to the gap being reduced by almost half.Footnote 14

In summary, our illustration shows that looking at the group-specific treatment effects of interventions should be expanded by consideration of take-up rates and the level of upscaling when conclusions regarding inequalities at the aggregate level are drawn.

5 Discussion

Educational programs aimed at fostering enrollment in higher education for socially disadvantaged students have attracted much attention from politicians, practitioners, and researchers in the past decade. We contribute to this research by investigating the impact of a counseling program in Germany, which targets students from disadvantaged backgrounds in upper secondary schools. We focus on variations by immigrant status. Previous research uncovered the so-called enrollment advantage of immigrants, although we reconceptualized this pattern as a native disadvantage. We expected the program to particularly foster enrollment among natives of low social origin by motivating them to strive for ambitious goals. In addition, we went beyond a micro level estimation of treatment effects by explicitly looking at how enrollment rates at the aggregate level would be affected by the program. We investigated our research questions with unique data from an experimental study of a counseling program offered in upper secondary schools in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Our results show that natives of low social origin benefit strongly from counseling with respect to enrollment. If they participate in the program, their enrollment rate rises considerably by 22 percentage points. The size of the effect seems to be remarkable compared with other studies providing information and support to students of low social origin with effect sizes that rarely exceed 15 percentage points (Herbaut and Geven 2020, Fig. 2, right side). This is notable when taking into account that the interventions that have been previously observed to be particularly effective are more comprehensive and start earlier in the educational career than the program investigated in this study. By contrast, the program effect for immigrants of low social origin is only seven percentage points. This indicates a different reactivity to program participation, albeit the difference is not significant in our analyses. Furthermore, in contrast to our expectations the strong effect for natives appears not to stem from a program effect on the motive for upward mobility, but from a program effect on perceived costs. Although the strong positive treatment effect on enrollment for natives suggests that the program could reduce the immigration-specific enrollment gap, this might be slowed down by a lower willingness of natives to participate in the program compared with immigrants. Extrapolating our empirical findings to different levels of program upscaling, we illustrate that equality of enrollment rates would require a wide implementation of the program.

Our results have important implications for politicians, practitioners, and researchers, both in the field of educational inequality and in the field of educational programs. First, researchers in the field of educational programs may benefit from paying specific attention to the intersection of social origin and immigrant status in future research. For various educational programs that foster the transition to demanding educational tracks, heterogeneity based on immigrant status might conceal a positive impact of interventions for natives of low social origin if researchers only investigate the program’s average impact. In extreme cases, a program may appear to have no considerable impact on access to demanding educational tracks, even though it fosters enrollment in ambitious tracks of natives of low social origin.

Second, the results may stimulate research on educational inequality based on immigrant status. Against the overall lower educational attainment of immigrants than natives, upper secondary school graduates are particularly interesting, as immigrants who “survived” until school graduation are more likely to enroll than their native peers. However, as our analyses show, this pattern may weaken over time. Depending on the availability of programs fostering enrollment of (native) students of low social origin, the well-described advantage for immigrants in university access may decrease. Because counseling is highly promoted in many European countries and may be expanded in the coming years, researchers dealing with immigration-specific disparities should be aware of this possible consequence to understand future changes.

Third, our results are also interesting from a theoretical viewpoint. The advantage of immigrants in enrollment has been mainly explained by this group’s stronger striving for intergenerational upward mobility compared with natives (see Dollmann 2017, 2021; Salikutluk 2016; Tjaden and Hunkler 2017; for other explanations see Salikutluk 2016, p. 583 f.). We also observe this stronger motive for the upward mobility of immigrants in our sample before treatment begins. However, contrary to our expectations, we cannot confirm that the strong treatment effect for natives on enrollment is driven by the program fostering their motive for upward mobility. It even appears that immigrants’ motive for upward mobility was further strengthened by the program. Instead, our results suggest that the strong native effect might be due to changing perceptions of the costs of higher education. After program participation, natives perceived the costs to be considerably lower, whereas immigrants’ perception of costs was not mitigated by the program. Taken together, our results suggest that the mechanisms driving inequality without treatment (i.e., motive for upward mobility) might differ from the mechanisms that reduce inequality (i.e., perceived costs); at least, this seems to be the case for immigration-specific disparities in enrollment.

Fourth, although natives benefit strongly from program participation they are slightly more reluctant to take up the counseling offer than their immigrant peers. Both phenomena suggest that particular efforts to motivate native students to participate in counseling might be reasonable. However, this fact should not be misunderstood as native students being generally disadvantaged compared with immigrants. Differences in academic performance between natives and immigrants of equal social origin (e.g., Sudheimer and Buchholz 2021) may reflect obstacles immigrant students encounter in the acquisition of academic skills in schools. Furthermore, the results should not be interpreted to mean that immigrants do not benefit from counseling at all. Although the program’s effect on their enrollment was indeed relatively weak, immigrants may nevertheless benefit from professional support regarding their educational career within higher education.

We note some limitations of our study and avenues for future research. First, we are not able to describe concrete processes that took place during the counseling sessions that may explain the different reactivity of native and immigrant students. It could be the case that participants just processed information differently. Such differences in information processing have been observed in other (highly standardized) interventions with different reactions of men and women (Finger et al. 2020; Erdmann et al. 2023). Furthermore, counselors may have acted differently depending on students’ needs in the semi-standardized setting of the investigated program and may have responded constructively to students’ needs as reflected in our baseline measurement before program participation. Because of the counselors’ flexibility in responding to participants’ needs, we cannot say which components of the intervention influenced natives’ cost estimates. However, our results suggest that natives of low social origin might benefit from information about the costs of higher education. This is remarkable as otherwise information sessions, which provide information on costs and benefits of higher education in a group setting, do not influence the enrollment of socially disadvantaged individuals if native and immigrant students are considered simultaneously (e.g., Barone et al. 2017; for an overview: Herbaut and Geven 2020). Finally, we cannot rule out counselors possibly discriminating against immigrants. However, in a recent German study on the same program investigated here, immigrants reported that they experienced positive personal regard by their school counselors (Schuchart and Siebel 2022).

Second, the weak effect for immigrants might be explained by spillover effects among this group. By violating the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (see Angrist et al. 1996), such spillover effects would bias the estimation of the treatment effect downward. However, spillover effects may occur for both groups and for both groups the estimate would be downwardly biased. Only in the case that spillover effects were higher among immigrants would the estimated difference be upwardly biased—a possibility that we cannot exclude but consider not very likely.

Third, higher enrollment rates of immigrants in higher education than those of natives are observed in several European countries. And also in the United States, some groups of immigrants or racial minorities have been observed to enroll more frequently in college than native students or white students when background characteristics such as social origin and academic performance are controlled (Belasco 2013, p. 793; López Turley 2009, p. 136). Whether effect heterogeneity of counseling based on immigrant status or race among students of low social origin can be observed outside Germany may be the subject of future research. Furthermore, we have not applied an important differentiation of immigrant students, that is, country of origin. As particularly students with a background from Turkey are known to strive ambitiously for education (e.g., Salikutluk 2016), future research may uncover heterogeneity by country of origin regarding program effects and macro-level implications. More specifically, for students of low social origin with a background from Turkey, the program effect may be even smaller and the program may need to be even more widespread to equalize enrollment rates between natives and immigrants than indicated by our results.

Fourth, we based our illustration of different extents of upscaling on observations and estimates from an experimental study. In fact, scaling a program based on results gained in field experiments is far from trivial (Al-Ubaydli et al. 2021; see Lundberg 2022). For example, parameters may change during program expansion owing to adaptations of involved, interrelated actors, such as schools, counselors, or universities, or spillover effects for schools, counselors, or universities. Still, we consider the methodological refinement of how interventions potentially influence educational disparities at the aggregate level to be a contribution to research in sociology of education. Aggregation issues have not yet been the subject of considerable interest. We hope our illustration will stimulate further methodological developments in this field that extend beyond research that merely reports treatment effects. Experimental research designs could be developed that randomly vary the share of treated units to find out if, for example, nonlinear relationships exist at the lower and upper ends of upscaling.

Finally, the study examined enrollment as the first step after high school completion. Future research should investigate how natives and immigrants of low social origin who were motivated to enroll by the program perform within higher education and whether they are equally successful as students who would have pursued higher education, regardless of the program. Not only would this be relevant to the evaluation of the program, but such an investigation would approach the consequences of immigrants’ ambitious choices (see Dollmann and Weißmann 2020; Klein and Neugebauer 2023; Tjaden and Hunkler 2017) from an innovative perspective.

The present study finds that intensive guidance counseling targeting students of low social origin can increase enrollment in higher education, especially among native students, and, if widely implemented, may strongly reduce the native disadvantage at the aggregate level. Our study contributes to the sociology of education by pointing out that the reluctance of students from lower social origins to enroll may be mitigated by specific and well-targeted support. However, students of low social origin are by far not homogeneous and may have different support needs. Our perspective, which considers students of low social origin with and without immigrant background and overcomes implicit assumptions concerning those categorized as the norm and deviation, teaches that native students of low social origin are a particularly disadvantaged group with respect to their university decision-making. More generally, research on educational inequalities at the micro and macro levels will benefit from moving away from separate analyses of specific social dimensions to exploring blind spots regarding heterogeneity within disadvantaged groups in theoretical considerations, implicit normative assumptions, and empirical approaches.

Notes

The trial is registered at the Social Science Registry under ID AEARCTR-0002738: https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/2738. Present analyses are post hoc as the details of the analysis plan of this paper were not part of the registration.

The selection of schools was based on an index of socio-structural disadvantage provided by Isaac (2011), which includes, for example, the share of unemployed individuals and individuals receiving social welfare in the neighborhood. Gymnasien and Gesamtschulen are included in the sample.

In accordance with scientific standards, the randomization was conducted by a researcher outside the study’s research team, namely a researcher from GESIS (Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences).

Panel attrition was equally distributed between experimental conditions on predictors of university enrollment, namely on the intention to enroll in higher education and academic achievement, as measured in the baseline wave (see Table A4 in the Online Appendix). In the analytical sample of students from low social origins, panel attrition was equally distributed across experimental conditions for immigrants. For natives, a slight selection bias that works in favor of our hypotheses is visible, as some students with relatively low achievement and intention to enroll in the treatment condition refrained from further participation. However, as only a few students dropped out, the slightly unequal drop-out did not lead to an unequal distribution of predictors across experimental conditions in the remaining analytical sample.

In wave 4, 563 persons from low social origins participated, i.e. 20% panel attrition.

Within the groups of natives and immigrants from low social origins, the randomization did not perfectly equalize the distribution of important predictors of enrollment across experimental conditions (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix). This slight deviation from an equal distribution works against our hypothesis, as immigrants assigned to the treatment condition showed slightly higher levels of academic performance at baseline than immigrants assigned to the control condition.

Our illustration of the different extents of upscaling is based on several assumptions. Most importantly, \(\overline{Y}^{j0}\) and LATEj are assumed to be generalizable over the population. As self-selection into program participation among individuals to whom the program is offered is explicitly considered in Eq. 3, this relevant threat to the external validity of treatment effects is considered. However, selection into study participation at the school and individual level may lead to deviations of \(\overline{Y}^{j0}\) and LATEj that we are unable to detect.

The group-specific compliance rate to treatment assignment can work as an approximation of TUj under real-world conditions. However, compliance rates to treatment assignment might slightly overestimate TUj, as study participants are potentially already positively selected based on their willingness to take part in the program. Because this applies to both natives and immigrants, conclusions about the program’s impact on the immigration-specific difference in university enrollment should be largely unaffected by this circumstance.

A description of immigrant students by generation status and country of origin is provided in the Appendix (Table A6 in Online Appendix)—a differentiation that has been used in previous research (e.g., Gresch and Kristen 2011; Kristen et al. 2008). Owing to low case numbers, we refrain from differentiations by immigration-generation status or country of origin in our analyses. However, particularly immigrant individuals of the third generation may be heterogeneous regarding the importance they assign to obstacles connected to their family history of migration. Therefore, we run further robustness checks with a different specification of immigrant status. More specifically, when immigrant individuals of the third generation are excluded from the analysis, the main results do not change substantially (see section “Results” and Table C4 in the Online Appendix).

The difference in the above-reported participation effect of 7 percentage points for immigrants is due to rounding.

The difference in take-up between natives and immigrants reaches statistical significance only if a loose criterion for significance is applied (Chi-squared test, p < 0.10, one-tailed; n = 281).

This value can be easily gained when group-specific estimates for \({\overline{Y}}_{\mathrm{agg}}^{j}\) are compared at a given level of upscaling.

If we focus on schools with socially disadvantaged students, where the extent of implementation is 40%, we see that natives’ enrollment increased by seven percentage points and immigrants’ enrollment by two percentage points. Consequently, the initial immigration-specific disparity in university access of nine percentage points is reduced to four percentage points, corresponding to lowering the initial gap by more than half.

References

Al-Ubaydli, Omar, Min Sok Lee, John A. List, Claire L. Mackevicius and Dana Suskind. 2021. How Can Experiments Play a Greater Role in Public Policy? Twelve Proposals from an Economic Model of Scaling. Behavioral Public Policy 5(1):2–49.

Angrist, Joshua D., Guido W. Imbens and Donald B. Rubin. 1996. Identification of Causal Effects Using Instrumental Variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association 91:444–455.

Barone, Carlo, Antonio Schizzerotto, Giovanni Abbiati and Gianluca Argentin. 2017. Information Barriers, Social Inequality, and Plans for Higher Education: Evidence from a Field Experiment. European Sociological Review 33(1):84–96.

Becker, Birgit, and Cornelia Gresch. 2016. Bildungsaspirationen in Familien mit Migrationshintergrund. In Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf, eds. Claudia Diehl, Christian Hunkler and Cornelia Kristen, 73–116. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Belasco, Andrew S. 2013. Creating College Opportunity: School Counselors and Their Influence on Postsecondary Enrollment. Research in Higher Education 54:781–804.

Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. New York: Wiley.

Breen, Richard, and John H. Goldthorpe. 1997. Explaining Educational Differentials: Towards a Formal Rational Action Theory. Rationality and Society 9(3):275–305.

Brinbaum, Yael, and Christine Guégnard. 2013. Choices and Enrollments in French Secondary and Higher Education: Repercussions for Second-Generation Immigrants. Comparative Education Review 57(3):481–502.

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). 2010. Bericht zur Umsetzung des Bologna-Prozesses in Deutschland. Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/shareddocs/downloads/files/umsetzung_bologna_prozess_2007_09.pdf (Accessed: 18 April 2023).

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). 2019. Forschungsschwerpunkt Abbau von Bildungsbarrieren. https://www.empirische-bildungsforschung-bmbf.de/de/Abbau-von-Bildungsbarrieren-1750.html) (Accessed: 18 April 2023).

Busse, Robin, and Katja Scharenberg. 2022. How Immigrant Optimism Shapes Educational Transitions Over the Educational Life Course: Empirical Evidence from Germany. Frontiers in Education 7.

Castleman, Benjamin L., Laura Owen and Lindsay C. Page. 2015. Stay Late or Start Early? Experimental Evidence on the Benefits of College Matriculation Support from High Schools versus Colleges. Economics of Education Review 47:168–179.

DiPrete, Thomas A., and Brittany N. Fox-Williams. 2021. The Relevance of Inequality in Sociology for Inequality Reduction. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7:1–30.

Dollmann, Jörg. 2017. Positive Choices for All? SES- and Gender-Specific Premia of Immigrants at Educational Transitions. Research on Social Stratification and Mobility 49:20–31.

Dollmann, Jörg. 2021. Ethnic Inequality in Choice- and Performance-Driven Education Systems: a Longitudinal Study of Educational Choices in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The British Journal of Sociology 72(4):974–991.

Dollmann, Jörg, and Markus Weißmann. 2020. The Story After Immigrants’ Ambitious Educational Choices: Real Improvement or Back to Square One? European Sociological Review 36:35–47.

Ehlert, Martin, Claudia Finger, Alessandra Rusconi and Heike Solga. 2017. Applying to College. Do Information Deficits Lower the Likelihood of College-eligible Students from Less-Privileged Families to Pursue their College Intentions?—Evidence from a Field Experiment. Social Science Research 67:193–212.

Engzell, Per. 2019. Aspiration Squeeze: The Struggle of Children to Positively Selected Immigrants. Sociology of Education 92(1):83–103.

Erdmann, Melinda, Irena Pietrzyk, Marcel Helbig, Marita Jacob and Stefan Stuth. 2022. Do Intensive Guidance Programs Reduce Social Inequality in the Transition to Higher Education in Germany? Experimental Evidence from the ZuBAb Study 0.5 years after High School Graduation. WZB Discussion Paper, P 2022-001. https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2022/p22-001.pdf (Accessed: 11 Aug. 2023).

Erdmann, Melinda, Juliana Schneider, Irena Pietrzyk, Marita Jacob and Marcel Helbig. 2023. The Impact of Guidance Counselling on Gender Segregation: Major Choice and Persistence in Higher Education. An Experimental Study. Frontiers in Sociology 8:1–15.

Erikson, Robert, and Jan O. Jonsson. 1996. Explaining Class Inequality in Education: the Swedish Test Case. In Can Education be Equalized? The Swedish Case in Comparative Perspective, eds. Robert Erikson and Jan O. Jonsson, 1–64. Boulder: Westview Press.

Fekjær, Silje Noack, and Gunn Elisabeth Birkelund. 2007. Does the Ethnic Composition of Upper Secondary Schools Influence Educational Achievement and Attainment? A Multilevel Analysis of the Norwegian Case. European Sociological Review 23(3):309–323.

Finger, Claudia, Heike Solga, Martin Ehlert and Alessandra Rusconi. 2020. Gender Differences in the Choice of Field of Study and the Relevance of Income Information: Insights From a Field Experiment. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 65:100457.

Gast, Melanie Jones. 2022. Reconceptualizing College Knowledge: Class, Race, and Black Students in a College-Counseling Field. Sociology of Education 95(1):43–60.

Gresch, Cornelia, and Cornelia Kristen. 2011. Staatsbürgerschaft oder Migrationshintergrund? Ein Vergleich unterschiedlicher Operationalisierungsweisen am Beispiel der Bildungsbeteiligung. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 40(3):208–227.

Griga, Dorit. 2014. Participation in Higher Education of Youths With a Migrant Background in Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Sociology 40(3):379–400.

Griga, Dorit, and Andreas Hadjar. 2014. Migrant Background and Higher Education Participation in Europe: The Effect of the Educational Systems. European Sociological Review 30(3):275–286.

Heath, Anthony, and Yael Brinbaum. 2007. Guest Editorial. Explaining Ethnic Inequalities in Educational Attainment. Ethnicities 7(3):291–305.

Heath, Anthony F., Catherine Rothon and Elina Kilpi. 2008. The Second Generation in Western Europe: Education, Unemployment, and Occupational Attainment. Annual Review of Sociology 34:211–235.

Herbaut, Estelle, and Koen Geven. 2020. What works to reduce inequalities in higher education? A systematic review of the (quasi-)experimental literature on outreach and financial aid. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 65:100442.

Isaac, Kevin. 2011. Neues Standorttypenkonzept. Faire Vergleiche bei Lernstandserhebungen. Schule NRW 06/11. https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/e/upload/download/mat_11-12/Amtsblatt_SchuleNRW_06_11_Isaac-Standorttypenkonzept.pdf (Accessed: 6 May 2022).

Jackson, Michelle, and David R. Cox. 2013. The Principles of Experimental Design and their Application in Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 19:27–49.

Jackson, Michelle, Jan O. Jonsson and Frida Rudolphi. 2012. Ethnic Inequality in Choice-Driven Education Systems: a Longitudinal Study of Performance and Choice in England and Sweden. Sociology of Education 85:158–178.

Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1995. Optimism and Achievement: The Educational performance of Immigrant Youth. Social Science Quarterly 76(1):1–19.

Keller, Tamás, Károly Takács and Felix Elwert. 2022. Yes, You Can! Effects of Transparent Admission Standards on High School Track Choice: A Randomized Field Experiment. Social Forces 101(1):341–368.

Klein, Daniel, and Martin Neugebauer. 2023. A Downside to High Aspirations? Immigrants (Non-) Success in Tertiary Education. Acta Sociologica. 66(4):448–467.

Kristen, Cornelia. 2016. Migrationsspezifische Ungleichheiten im deutschen Hochschulbereich. In Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf: Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten, eds. Claudia Diehl, Christian Hunkler and Cornelia Kristen, 643–668. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kristen, Cornelia, David Reimer and Irena Kogan. 2008. Higher Education Entry of Turkish Immigrant Youth in Germany. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49(2–3):127–151.

López Turley, Ruth N. 2009. College Proximity. Mapping Access to Opportunity. Sociology of Education 82(April):126–146.

Lörz, Markus. 2019. Intersektionalität im Hochschulbereich: In welchen Bildungsphasen bestehen soziale Ungleichheiten nach Migrationshintergrund, Geschlecht und sozialer Herkunft – und inwieweit zeigen sich Interaktionseffekte. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 22(1):101–124.

Lundberg, Ian. 2022. The Gap-Closing Estimand: A Causal Approach to Study Interventions That Close Disparities Across Social Categories. Sociological Methods & Research. Online First:1–64.

Mentges, Hanna. 2019. Studium oder Berufsausbildung? Migrationsspezifische Bildungsentscheidungen von Studienberechtigten. Eine kritische Replikation und Erweiterung der Studie von Kristen et al. (2008). Soziale Welt 70(4):403–434.

Neumeyer, Sebastian, Melanie Olczyk, Miriam Schmaus and Gisela Will. 2022. Reducing or Widening the Gap? How the Educational Aspirations and Expectations of Turkish and Majority Families Develop During Lower Secondary Education in Germany. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 74:259–285.

Olczyk, Melanie, Gisela Will and Cornelia Kristen. 2014. Personen mit Zuwanderungshintergrund im NEPS. Zur Bestimmung von Generationenstatus und Herkunftsgruppe. NEPS Working Paper No. 41b.

Peter, Frauke H., and Vaishali Zambre. 2017. Intended College Enrollment and Educational Inequality: Do Students Lack Information? Economics of Education Review 60:125–141.

Pietrzyk, Irena and Melinda Erdmann. 2020. Investigating the Impact of Interventions on Educational Disparities: Estimating Average Treatment Effects (ATEs) is Not Sufficient. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 65:100471.

Pietrzyk, Irena, Jutta Allmendinger, Melinda Erdmann, Marcel Helbig, Marita Jacob and Stefan Stuth. 2019. Future and Career Plans before High School Graduation (ZuBAb): Background, Research Questions and Research Design. Discussion Paper P 2019–004. https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2019/p19-004.pdf (Accessed: 20 June 2023)

Qualification for Counselors. n. d. [Weiterbildung zum NRW-Talentscout.] https://www.nrw-talentzentrum.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Redakteure/Downloaddaten/Druckdaten/Weiterbildung_zertifizierte_Talentscouts/221123_Qualifizierung_zum_NRW-Talentscout_web.pdf (Accessed: 12 Jan. 2023).

Relikowski, Ilona, Erbil Yilmaz and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 2012. Wie lassen sich die hohen Bildungsaspirationen von Migranten erklären? Eine Mixed-Methods-Studie zur Rolle von strukturellen Aufstiegschancen und individueller. In Soziologische Bildungsforschung, eds. Rolf Becker and Heike Solga, 111–136. Special Issue 52, Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Robinson, Karen Jeong, and Josipa Roksa. 2016. Counselors, Information, and High School-Going Culture: Inequality in the College Application Process. Research in Higher Education 57:845–868.

Salikutluk, Zerrin. 2016. Why Do Immigrant Students Aim High? Explaining the Aspiration–Achievement Paradox of Immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review 32(5):581–592.

Sattin-Bajaj, Carolyn, Jennifer L. Jennings, Sean P. Corcoran, Elizabeth Christine Baker-Smith and Chantal Hailey. 2018. Surviving at the Street Level: How Counselors’ Implementation of School Choice Policy Shapes Students’ High School Destinations. Sociology of Education 91(1):46–71.

Schuchart, Claudia, and Angelika Siebel. 2022. Counselling of Immigrant Students in Schools—the Development of Shared Understanding between Advisers and Students. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 51(5):820–834.

See, Beng Huat, Stephen Gorard and Carole Torgerson. 2012. Promoting Post-16 Participation of Ethnic Minority Students from Disadvantaged Backgrounds: a Systematic Review of the Most Promising Interventions. Research in Post-Compulsory Education 17(4):409–422.

Shavit, Yossi, Richard Arum and Adam Gamoran. 2007. Stratification in Higher Education. A Comparative Study. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Sudheimer, Swetlana, and Sandra Buchholz. 2021. Muster migrationsspezifischer Unterschiede unter Studienberechtigten in Deutschland: Soziale Herkunft – Schulische Leistungen – Bildungsaspirationen. In Migration, Mobilität und soziale Ungleichheit in der Hochschulbildung, Higher Education Research and Science Studies, eds. Monika Jungbauer-Gans and Anja Gottburgsen, 27–58. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Tjaden, Jasper Dag, and Christian Hunkler. 2017. The Optimism Trap: Migrants’ Educational Choices in Stratified Education Systems. Social Science Research 67:213–228.

Vallet, Louis-André. 2006. What Can We Do to Improve the Education of Children from Disadvantaged Backgrounds? Paper prepared for the Joint Working Group on Globalization and Education of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Vatican City. http://www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/es7/es7-vallet.pdf (Accessed: 6 May 2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues in the ZuBAb-project, Marcel Helbig, Juliana Schneider and Jutta Allmendinger, for their joint work.

Funding

This project was supported by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (MKW-NRW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the MKW-NRW.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Irena Pietrzyk provided the idea for the paper and planned it. She was in charge of data collection, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. Marita Jacob helped to plan and write the paper, and revised it during the writing process. Melinda Erdmann was in charge of data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

I. Pietrzyk, M. Jacob, and M. Erdmann declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All human subjects gave their informed consent prior to their participation in the research and adequate steps were taken to protect participants’ confidentiality. The project was approved by the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB) Institutional Review Board, and was pre-registered on the platform social science registry: https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/2738/

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Online Appendix: https://kzfss.uni-koeln.de/sites/kzfss/pdf/Pietrzyk-et-al.pdf

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pietrzyk, I., Jacob, M. & Erdmann, M. Who Benefits from Guidance Counseling? Insights into Native and Immigrant Students of Low Social Origin. Köln Z Soziol 75, 395–417 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-023-00921-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-023-00921-3