Abstract

Many empirical studies have demonstrated positive ethnic choice effects at the transition to upper secondary education. This means that ethnic minority students—given the same academic performance, parental resources and type of school at lower secondary level—aspire to more demanding educational programs than ethnic majority students. Previous research has often examined only single cohorts of school-leavers and has rarely considered differences between ethnic minority generations. Therefore, little is known about the extent to which these positive ethnic choice effects vary over time and across minority generations. The aim of this paper is to fill this gap using large-scale survey data from Switzerland (2000–2016; N = 100,495). Using multilevel analyses, I am able to show that positive ethnic choice effects are persistent over time in Switzerland. Furthermore, it becomes clear that positive ethnic choice effects vary across ethnic minority generations, with these effects decreasing with each succeeding minority generation. Ethnic minority students with one parent born in Switzerland hardly differ from ethnic majority students in their educational decisions.

Zusammenfassung

Viele empirische Studien haben positive ethnische Wahleffekte beim Übergang in die Sekundarstufe II nachgewiesen. Das bedeutet, dass Schülerinnen und Schüler mit Migrationshintergrund – bei gleichen schulischen Leistungen, gleichen elterlichen Ressourcen und gleichem besuchtem Schultyp in der Sekundarstufe I – anspruchsvollere Bildungsprogramme anstreben als Schülerinnen und Schüler ohne Migrationshintergrund. Bisherige Forschungsarbeiten haben oft lediglich einzelne Kohorten von Schulabgängern untersucht und selten Unterschiede zwischen dem Generationenstatus von Schülerinnen mit Migrationshintergrund berücksichtigt. Daher ist wenig darüber bekannt, inwieweit positive ethnische Wahleffekte im Laufe der historischen Zeit und zwischen den Migrantengenerationen variieren. Ziel der vorliegenden Arbeit ist es, diese Lücke mit Hilfe von umfangreichen Befragungsdaten aus der Schweiz (2000–2016; N = 100.495) zu schließen. Mithilfe von Mehrebenenanalysen kann ich zeigen, dass positive ethnische Wahleffekte in der Schweiz über die Zeit persistent sind. Darüber hinaus wird deutlich, dass positive ethnische Wahleffekte zwischen den Generationen von Minderheiten variieren. Positive ethnische Wahleffekte nehmen über die Minderheitengeneration hinweg ab. Schülerinnen und Schüler mit Migrationshintergrund mit einem in der Schweiz geborenen Elternteil unterscheiden sich in ihren Bildungsentscheidungen kaum mehr von Schülern ohne Migrationshintergrund.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Various studies show persistent ethnic disadvantages in the educational system. Ethnic minority students show lower academic achievement, are less likely to pursue an academic track, and are more often found on tracks with lower academic requirements (Heath and Brinbaum 2007; Heath et al. 2008; Heath 2014). Against the background of these clear disadvantages in the resource endowment of minority students, the consistent findings of positive ethnic choice effects from different countries are all the more compelling (for Germany: Kristen and Dollmann 2010; Dollmann 2017; Dollmann and Weißmann 2019; Tjaden 2017; Kristen et al. 2008; for France: Brinbaum and Guégnard 2013; Brinbaum and Cebolla-Boado 2007; for the UK: Jackson et al. 2012; for Sweden: Jonsson and Rudolphi 2011; for Norway: Fekjær and Birkelund 2007; for Finland: Kilpi-Jakonen 2011; for the Netherlands: van de Werfhorst and van Tubergen 2007; for Switzerland: Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017). Positive ethnic choice effects mean that after controlling for academic ability, type of school attended, and social background, minority students choose academic tracks significantly more often than native students. Thus, they make more ambitious choices than might be expected given their academic achievements and resource endowment (Dollmann and Weißmann 2019).

It is also interesting to note that positive ethnic choice effects at the transition to upper secondary education can also be found in countries with a very strong and rewarding vocational education and training (VET) system (Allmendinger 1989; Buchmann et al. 2016; Korber and Oesch 2019), such as Germany and Switzerland (for Germany: Kristen and Dollmann 2010; Dollmann 2017; Dollmann and Weißmann 2019; Tjaden 2017; Kristen et al. 2008; for Switzerland: Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Glauser 2018).

Previous studies of ethnic choice effects have often focused on the following analyses concerning the influence of ethnic origin: first, on the differences between majority and minority students (e.g., Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Dollmann 2017); second, on the comparison between majority students and different groups of minority students (e.g., Glauser 2018; Dollmann and Weißmann 2019)—analyses separated by minority groups are often calculated because there can be substantial differences in educational attainment, educational achievement, and social background among them (SCCRE 2018); and third, on differences between majority students and minority generations in general (e.g., Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Dollmann 2017). Generational status is taken into account, as it can be assumed that country-specific human capital increases over successive generations (Kilpi-Jakonen 2011). Several studies have indicated that minority students born in the host country show greater educational achievement and a better command of the local language than minority students born abroad (Esser 2008). The findings from these studies suggest that there might be significant differences in ethnic choice effects across minority groups (Dollmann 2017; Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017) and also across minority generations (e.g., Glauser 2018; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018).

However, hardly any studies present analyses of ethnic choice effects separately for minority groups and migrant generations (e.g., Kilpi-Jakonen 2011). Thus, little is known about how the intersection between minority groups and migrant generation affects ethnic choice effects. Furthermore, many studies limit their analyses to a single cohort of school-leavers. Thus, little is known about how ethnic choice effects vary over time. For example, changes in immigration patterns (due to changing immigration policies) could cause these effects to vary over time, and selective migration might have an impact on minority–majority differences in educational attainment (Engzell 2019; Spörlein and Kristen 2019; Spörlein et al. 2020).

This descriptive paper goes beyond previous research on ethnic choice effects in two ways (and thereby attempts to fill gaps in the state of research): first, by considering a time dimension; and second, by differentiating minority groups by migrant generations. The focus of this paper is on the description of ethnic choice effects (using different indicators of minority status) over time. This paper is thus aimed at answering the following two research questions: are positive ethnic choice effects (for all minority students and differentiated by minority groups) at the transition to upper secondary academic education in Switzerland a time-persistent phenomenon? Are differences observed between minority generations in ethnic choice effects (for all minority students and differentiated by minority groups) at the transition to upper secondary academic education in Switzerland?

For my analyses, I use large-scale, cross-sectional survey data (PISA 2000–PISA 2012; and Überprüfung des Erreichens der Grundkompetenzen 2016 [ÜGK 2016]) from Switzerland that contain information on educational choices at the end of lower secondary school (9th Grade). In total, information from 100,495 students from six survey time points is used for the analyses. These surveys include a share between 10.0% (PISA 2000) and 26.7% (ÜGK 2016) of all 9th-graders enrolled in Switzerland in the respective year.

Switzerland is an interesting case for the study of ethnic choice effects at the transition to upper secondary education for several reasons. First, VET in Switzerland has a high reputation and is seen as a worthwhile educational alternative to academic education (Buchmann et al. 2016; Korber and Oesch 2019; Nennstiel 2021). Second, in Switzerland, one-third of 15- to 24-year-olds are minority students (BfS 2020). Third, the availability of the large-scale survey data used in this study makes it possible to analyze ethnic choice effects for several minority groups differentiated by generational status (first and second generations, as well as the 2.5 generation; Olczyk et al. 2014; Gresch and Kristen 2011).

In the next section, I briefly introduce the Swiss context before presenting the state of research on positive ethnic choice effects and the theoretical considerations. I then describe the data, operationalization, and statistical analysis procedures. This is followed by the presentation of my results. Finally, I discuss my findings and contextualize them within the current state of research.

2 Swiss Context

Switzerland has a highly stratified education system (Allmendinger 1989; Buchmann et al. 2016; Combet 2019), which is organized at the canton level. Despite cantonal differences, the transfer from primary school to the tripartite lower secondary school usually occurs after 6th Grade. At the lower secondary school level there are schools with basic requirements that prepare students for VET, alongside schools with extended requirements that prepare students both for VET and for more demanding upper secondary schools. In addition, the pre-Gymnasium prepares students for the Matura, which entitles students to study at university. In Switzerland, compulsory schooling ends after 9th Grade. Thereafter, the transition to upper secondary education takes place. At this point of transition, too, three dominant educational paths can be distinguished: entry to an academic track; entry to VET; and entry to an interim solution (e.g., repeating 9th Grade or the preparatory year for vocational training). The alternative to these is neither education nor employment (NEET) (SCCRE 2018).

Immediately following lower secondary school, 28% of students enter academic upper secondary education, 45% enter VET, and 11% engage in interim solutions, whereas the remainder do not choose any of these three paths (e.g., they have a gap year, or they enter the labor market) (SCCRE 2018). Failure to enter qualified upper secondary education directly (e.g., engaging in interim solutions) is associated with an increased risk of not graduating from upper secondary education (Sacchi and Meyer 2016). Minority students are at a higher risk for dropout than native students, both from the academic track and from VET (Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; SCCRE 2018).

Migration to Switzerland is often described as having occurred in waves (Fibbi et al. 2015; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018).Footnote 1 The first wave was the immigration of classical labor migrants from Italy and Spain, who were often unskilled. This immigration was based on bilateral treaties between Switzerland and Italy (1946 and 1964) and between Switzerland and Spain (1961). It is worth mentioning that the aim of these treaties was to prevent migrants from settling permanently in Switzerland. This policy was characterized by offering easy access to low-skilled jobs and making access to the benefits of the social system more difficult. From the beginning of the 1960s, Switzerland toughened its migration policy (reducing the number of foreign workers) as a result of increasing rejection of the previous migration policy among the population and a tense economic situation. As a result of the economic recovery in the 1980s, the demand for labor migrants increased. During this second wave, labor migrants mainly came from Portugal, Turkey, and Yugoslavia and were often unskilled workers, similar to the labor migrants of the first wave (Fibbi et al. 2015). These first two waves were well reflected in the distributions of foreign workers in Switzerland over time. In 1970, 56% of foreign workers were Italian citizens (1980: 44%; 1990: 31%), 14% were Spanish citizens (1980: 13%; 1990: 11%), 0.4% were Portuguese citizens (1980: 3%; 1990: 10%), 1.2% were Turkish citizens (1980: 4%; 1990: 6%), and 3.2% were citizens of Yugoslavia (1980: 8%; 1990: 14%) (Farago et al. 1996).

As a result of the Yugoslav Wars, a large number of refugees moved to Switzerland in the early 1990s. In the mid-1990s, the economic situation in Switzerland deteriorated again and immigration policy was adapted once more. A so-called “three circles model” was introduced, based on the cultural distance of migrants’ countries of origin. For people from the first circle (the EU and EFTA), there were no quotas. For people from North America and Eastern Europe (the second circle), there were limited quotas, whereas immigrants from all other countries were only granted entry permits if they were highly qualified. Moreover, there was a possibility of immigration for family reunification and via asylum. In 2002, a bilateral agreement between Switzerland and the EU came into force, granting EU and EFTA citizens free access to the Swiss labor market (fully implemented as of 2008). For persons from non-EFTA countries, the rules were further adapted to allow only highly qualified people access to the Swiss labor market (Fibbi et al. 2015).

The adjusted immigration framework from the mid-1990s onward led to a third wave of migration comprising mainly people from the EU and neighboring countries (Cattaneo and Wolter 2015; Griga 2014). Notable in this regard was the change in the educational qualifications of working-age immigrants. In the 1990s, 10% of them had a university degree, whereas in 2009 the figure was 60% (SCCRE 2014). This shows a trend toward tertiary educational qualifications over time for both EU/EFTA and other immigrants (EU/EFTA 1986–1995: 27%; 1995–2002: 48%; 2002–2009: 54%; other immigrant groups 1986–1995: 11%; 1995–2002: 33%; 2002–2009: 41% [Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft 2011]). Among EU citizens, there were some large differences in educational attainment. For example, in 2005, over half (52%) of German nationals (2010: 52%; 2015: 55%) and 46% of French nationals (2010: 52%; 2015: 55%) had a university degree, compared with 11% of Italians (2010: 14%; 2015: 23%) and 14% of Spaniards (2010: 18%; 2015: 28%) had a university degree (BfS 2022).

In addition to their respective migration wave or geographic relation to Switzerland (e.g., neighboring countries), the classification of minority groups for empirical analysis often also considers their social structural position (Glauser 2018; Nennstiel 2022; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017). In terms of the “ethnic hierarchies” (Hagendoorn 1995) of migrant groups in Switzerland, it is noticeable that migrants from Turkey and the Balkans face the greatest disadvantages in the education system and in the labor market. For Northwest European migrants (e.g., from Germany, France, and Austria), hardly any disadvantages are observed owing to selective immigration. The Southern Europeans (from Italy, Spain, and Portugal) are situated between these two groups (Zschirnt 2020, 2019; Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft 2018). These hierarchies are also evident in the social origins of students in the data used in this study (see Fig. 1).Footnote 2

Socioeconomic background (highest parental ISEI, HISEI) of the student population over time and minority group. Estimates based on m = 50 multiple imputed datasets; my own calculations. GER Germany, FRA France, AUT Austria, BEL Belgium, IT Italy, SP Spain, POR Portugal, TUR Turkey. (Source: PISA 2000–PISA 2012; ÜGK 2016)

When examining disparities between natives and minority students, minority students are often differentiated not only by their regional origin, but also by their generational status (Olczyk et al. 2014). The first minority generation indicates that the students themselves and their parents were born abroad. If the students were born in the host country and the parents were born abroad, this is referred to as the second generation. If, in addition to the child, at least one parent was born in the host country, this generation is referred to as the 2.25–3.75 generation, depending on the place of birth of the grandparents.Footnote 3 The data used in this study (see Fig. 2) also show effects indicating that the generational composition of the minority groups varies greatly depending on the migration wave and migration groups. In the group of classical labor migrants of the first wave (Italy, Spain, and Portugal), a large share of the children belong to the second generation and the 2.5 generation. However, the situation is different for minority students from the Balkans and Turkey. Here one can see a strong effect of the Yugoslav Wars (a very high proportion of first-generation minority students in 2000 and 2003): there are fewer children of the 2.5 generation, and from 2009 onward most of the children belong to the second generation. Accordingly, this group is also referred to as the “new second generation,” distinct from the second generation of the first wave of immigration (Fibbi et al. 2015). In the group of neighboring countries, it is noticeable that a large proportion of the children have one parent born in Switzerland. The slight increase in the number of first-generation students in neighboring countries—and also in the number of students from Southern European EU countries—could be due to changes in immigration policies since the mid-1990s. As a result, more people from these countries have immigrated to Switzerland.

3 State of Research and Theoretical Considerations

A consistent and persistent research finding in educational research is that minority students show lower academic abilities, are overrepresented on less demanding school tracks, and are underrepresented on academic tracks compared with natives (e.g., Meunier 2011; Contini and Azzolini 2016; Borgna and Contini 2014; Veerman and Dronkers 2016; Spörlein and Schlueter 2018). These patterns are also evident for Switzerland (SCCRE 2018). Administrative data (BfS 2020) show that 26% of Swiss students attend the upper secondary academic track. For students from the Balkans (8%) and Turkey (12%), these percentages are considerably lower. In contrast, students from neighboring countries, such as France (49%) and Germany (38%), are notably more likely to attend the academic track than natives.

Taking into account academic ability, social background, and prior educational choices, positive ethnic choice effects are found in many European countries (e.g., Jackson et al. 2012; Brinbaum and Guégnard 2013; Kilpi-Jakonen 2011; van de Werfhorst and van Tubergen 2007; Tjaden 2017). This means that, if minority students had the same academic abilities and the same parental resources and pursued the same lower secondary school tracks, minority students would choose upper secondary academic tracks more often than native students. With regard to educational aspirations, it is also evident that, taking into account the abovementioned factors, minority students show more ambitious educational aspirations (e.g., Salikutluk 2016; for an overview of recent aspiration studies from Germany, see Becker and Gresch 2016). Although educational choices and educational aspirations are not congruent, educational choices are strongly influenced by educational aspirations. Furthermore, aspirations adapt during the decision process (Gottfredson 1981; Heckhausen and Tomasik 2002) and can thus be very predictive of actual choices. It can thus be theorized that (realistic) educational aspirations are increasingly adjusted as the decision point approaches (Becker and Gresch 2016).

Interestingly, positive ethnic choice effects are evident at different points in the education system of countries that have prominent and financially rewarding VET systems, such as Germany and Switzerland (for Germany: Kristen and Dollmann 2010; Dollmann 2017; Dollmann and Weißmann 2019; Tjaden 2017; Kristen et al. 2008; for Switzerland: Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017). For Germany, Dollmann (2017) showed positive ethnic choice effects in the transition to upper secondary academic education of 13 percentage points. For the same educational transition, Dollmann and Weißmann (2019) found similarly large positive ethnic choice effects in a dataset restricted to students who did not attend the academic track in lower secondary education. These were particularly pronounced for the group of Turks and for students from either the former Yugoslavia or the republics established after the break-up of Yugoslavia. For children from Northern and Western Europe, the positive ethnic choice effects were the largest in terms of magnitude. However, this group had significantly higher transition rates than natives, even without taking control variables into account. For Switzerland, Tjaden and Scharenberger (2017), using data based on the PISA2000 sample, detected positive ethnic choice effects of eight percentage points at the transition to upper secondary academic education. These positive ethnic choice effects were found to be particularly strong for students from Spain and Portugal (10 percentage points) and from the Balkans and Turkey (13 percentage points). Wolter and Zumbuehl (2018) were also able to identify ethnic premia at this transition based on Swiss PISA2012 sample data linked to administrative data (9 percentage points). They also found particularly strong positive ethnic choice effects for students from the Balkans (7.5%), from Portugal (6%), and from neighboring countries (6%).

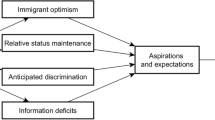

As the focus of this paper, as mentioned above, is to show descriptive changes over time and across minority generations in ethnic choice effects, I only briefly discuss the most common explanations for ethnic choice effects in the literature (for a detailed discussion of different theoretical explanations for higher educational aspirations among minority students, see Becker and Gresch 2016). The explanations are presented in an effort to derive expectations about the extent to which ethnic choice effects might vary over time and across minority generations.Footnote 4

Following the seminal work of Kao and Tienda (1995), immigrant optimism came into focus as an explanation for ambitious educational choices. Minority students might have higher educational aspirations, as individuals who migrate are a selective group and also migrate in order to provide a better life for themselves and their children (Kao and Tienda 1995, 1998). Accordingly, higher aspirations might be transferred from parents to children. Moreover, it can be argued that, if parents do not manage to achieve an advantageous position in the host country (for example, because their qualifications are not recognized and they therefore have to work in a job for which they are overqualified), their aspirations are transferred to their children. Various studies show that minority students have higher aspirations in regard to social upward mobility than native students (Salikutluk 2016; Heath and Brinbaum 2007).

Another mechanism that is often discussed in the context of the high educational aspirations of minority students is that of an information deficit (Kristen and Olczyk 2013; Forster and van de Werfhorst 2020). As migrant parents have not gone through the educational system themselves, they might underestimate the benefits of VET and overestimate the likelihood of success in academic education. Furthermore, it could be argued that VET is not well-known in many countries, whereas universities exist all over the world.

The preference of minority students for academic education could also be a reaction to expected discrimination in the apprenticeship market (Heath and Brinbaum 2007; Jonsson and Rudolphi 2011). Many experimental application studies have provided evidence that migrants—especially those from Turkey and the Balkans—are discriminated against during the application process (Lancee 2021; for Switzerland: Zschirnt 2019, 2020). To circumvent this discrimination, minority students may remain in the education system for longer in the hope that such discrimination will be less severe in labor market segments that require higher education certificates (Jackson et al. 2012).

In the following, I outline my theoretical expectations and derive hypotheses. First, I discuss in general terms the extent to which ethnic choice effects can be expected according to minority status, minority group, and minority generation (H 1–H 3). I then discuss how these expected effects may vary over time (H 4–H 6). Finally, I discuss the extent to which ethnic choice effects for the intersection of minority group and minority generation may change over time (H 7). Based on previous research, the following hypothesis is derived for the Swiss context:

H 1

There are positive ethnic choice effects at the transition to upper secondary academic education.

Regarding the difference in ethnic choice effects between minority groups, based on previous research and theoretical explanations, these can be expected to be particularly strong for minority students from Turkey and the Balkans, because this group, for example, experiences the greatest discrimination in application processes and is socioeconomically the most disadvantaged. For the group of students from neighboring countries (e.g., France, Germany, and Austria), on the other hand, smaller positive ethnic choice effects are to be expected as they have greater participation in upper secondary academic education than natives, and the education and training system in Switzerland is similar to that of their country of origin. Furthermore, this group is on average socioeconomically similar to, or slightly better placed than majority students. The group of students from Southern Europe should be placed between these two groups.

H 2

Positive ethnic choice effects should be largest for minority students from the Balkans and Turkey and smallest for minority students from Northwestern Europe. The positive ethnic choice effects of minority students from Southern Europe are expected to fall between the two groups.

The following factors could influence disparities in ethnic choice effects between minority generations. First, it can be assumed that minority students born in the host country (second generation and above) have more information about the educational system of the host country, and also that they have higher country-specific human capital. Various studies reveal that younger minority generations are better integrated in school and better equipped with country-specific human capital (Esser 2009, 2008; Drouhot and Nee 2019). This could lead to less ambitious choices across generations. Furthermore, the high educational aspirations of minority students could converge with those of natives in the cohort sequence as a result of better social integration (Kao and Tienda 1995, 1998; Fleischmann and Kristen 2014). This could be reflected, for example, in the comparison between minority generations where parents were born in the host country (2.5 generation or above versus the first and second generation) and those where parents were not. Since these children have at least one parent born in the host country, they should have stronger language skills and more knowledge about the school and labor market system (Kilpi-Jakonen 2011). Research into the influence of generational status on positive ethnic choice effects in Germany and Switzerland is inconclusive. Regarding positive ethnic choice effects at the transition to upper secondary academic education, Tjaden and Scharenberg (2017) do not find any generational differences in Switzerland (undifferentiated by minority group). Wolter and Zumbuehl (2018) find stronger positive ethnic choice effects for second-generation minority students than for first-generation minority students in Switzerland (without controlling for attendance of lower secondary school and undifferentiated by minority group). For Germany, Dollmann (2017) shows that the largest positive ethnic choice effects are found for the first minority generation and that these become smaller over the following generations. Although the state of research is mixed, based on the theoretical considerations, positive ethnic choice effects are assumed to weaken over successive generations.

H 3

Across the generational sequence, positive ethnic choice effects decrease.

After formulating expectations about how ethnic choice effects might vary across minority groups and migrant generations, in the following I explain how the expected effects (by minority status, minority group, and minority generation) might vary over time. As research into changes in ethnic choice effects over time is scarce, I will limit myself to a discussion of why these effects might vary.

Regarding the general ethnic choice effect (undifferentiated by minority groups), the composition of minority students could have an impact on changes over time. The socioeconomic composition of migrants in a country could change, either through better social integration across migrant generations or through changes in immigration policies. As discussed above, a significant change in immigration policy occurred in Switzerland in the 1990s, which resulted in an increase in highly skilled immigrants (mainly from EU and EFTA countries) entering the country. The results of the PISA study clearly show that the composition of immigrants can have an impact on majority–minority differences. For example, test scores in math for first-generation minority students increased by 40 points between 2000 and 2009 (whereas test scores for native students did not increase), with 75% of this increase being attributable to the changing socioeconomic background (Cattaneo and Wolter 2015). The change in the minority composition (an increasing number of high-skilled immigrants) influenced by the change in immigration policy could lead to a weakening of positive ethnic choice effects over time. However, one could argue against this, because in the calculation of ethnic choice effects the social origin of the students is already controlled for. Yet, several studies show that ethnic choice effects are largest among groups that are socioeconomically most disadvantaged (Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018). This pattern could be caused by the fact that these groups try to improve their social position in the generational sequence through achieving upward mobility by acting on their ambitious educational aspirations (Salikutluk 2016). Therefore, I expect that positive ethnic choice effects should decrease over time.

H 4

Positive ethnic choice effects should become less pronounced over time.

Changes in the differences in educational choices between majority students and minority student groups over time could be caused by changes in the composition of minority students (e.g., the proportion of different minority generations or changes in the socioeconomic positioning of parents). For example, if the proportion of children in a minority group whose parents were born in the host country increases, this could lead to a convergence of educational choices between this minority group and the majority students. A similar process could be expected if the social integration of minority groups improves over time. Better socioeconomic placement of parents could lead to lower aspirations for upward mobility and thus to less ambitious educational choices. Positive ethnic choice effects have been most consistently observed for the group of students from the Balkans and Turkey (Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018). The economic integration of the parents of this minority group has hardly changed in relative terms (e.g., distance to native parents: see Fig. 1). However, the proportion of Swiss-born children in this group has increased considerably (see Fig. 2). This should lead to an increase in country-specific human capital and knowledge about the education system over time (e.g., since children from this group pass through the Swiss education system from the beginning), as well as to a convergence of the educational choices of these minority students with those of majority students. For the other minority groups, hardly any changes in the economic positioning of the parents or the generational composition were found. Therefore, I only assume a change in the ethnic choice effects of minority students from the Balkans and Turkey over time.

H 5

Positive ethnic choice effects for minority students from the Balkans and Turkey should decrease over time. The positive ethnic choice effects for the other minority groups should remain stable over time.

The changing composition of migrants (e.g., through changing immigration policies) could have an impact on the change in overall generational effects in Switzerland. If one follows the argument that an increase in higher-skilled migrants leads to their children making potentially less ambitious choices than majority children (see the reasoning for the justification of H 4 above), generational effects should decrease over time.

H 6

Positive ethnic generational choice effects should decrease over time.

Finally, as described above, I discuss the extent to which ethnic choice effects interacting with minority group and minority status may change over time. Looking at the intersection of minority group and minority generation over time means holding constant the group composition by generation status of each minority group. This means, for example, comparing ethnic choice effects for second-generation minority students from Southern Europe in 2000 with second-generation minority students from Southern Europe in 2016. Therefore, the abovementioned arguments regarding the changed composition of their generational status should have less explanatory power. Furthermore, as described above (e.g., see Fig. 1), the distance in the socioeconomic positioning of the parents of the minority groups compared with that of the majority group has hardly changed. I therefore assume that the ethnic choice effects differentiated by minority group and minority generation remain stable over time.

H 7

The positive ethnic choice effects differentiated by minority group and migrant generation remain stable over time.

4 Data

The analyses are based on several large-scale surveys from Switzerland: PISA (2000), PISA (2003), PISA (2006), PISA (2009), PISA (2012), and ÜGK (2016). All of these surveys interviewed 9th-graders shortly before the end of compulsory schooling (April–June of the year in question). Stratified random sampling was used to create the samples. Regions were selected within the participating cantons; schools were randomly selected within these regions; and then students were selected within their schools. An advantage of using these data is that the sampling is similar across waves. Furthermore, like many surveys conducted in school classes, these data have the advantage that over 90% of the selected students participated. For the analyses, I apply the design weights provided for schools and students (Verner and Helbling 2019; McCluskey and Zahner 2003).

4.1 Operationalization

The dependent variable is a dummy variable establishing whether a transition to an academic track is aimed at (1), or not (0: VET, interim solutions, or NEET).Footnote 5 I measure the educational choice for an academic track shortly before the students leave compulsory schooling (measurement time: April–June; upper secondary education usually starts in mid-August). This differs from most other ethnic choice studies, which measure educational choices using the factual transition one year after the end of compulsory schooling. Nevertheless, some studies also refer to ethnic choice effects, even though information on educational choices is being used before the transition to upper secondary education (e.g., Tjaden and Hunkler 2017). Furthermore, for the following reasons, I assume that the measurement used in this study should not generate substantial bias. First, in many cantons, entrance examinations or admissions procedures are required for access to academic tracks. At the time the surveys were conducted, which was between 16 weeks and 6 weeks before the beginning of upper secondary education, the registration procedures for the academic track schools had already been completed. Second, for those who want to enter the VET system, for example, it is common for apprenticeship positions to be already filled at the time the surveys were conducted (e.g., SBFI 2017). Third, it is known from aspiration research that aspirations are adjusted over time as the decision deadline approaches (Gottfredson 1981; Heckhausen and Tomasik 2002). Accordingly, possible adjustment processes in respect of educational decisions should be largely completed at the time of measurement. Fourth, the surveys explicitly asked about the probable educational path over the next school year after leaving compulsory schooling (“What training or activity will you probably start after the summer vacations?”). Fifth, further analysis (not shown) using data from the TREE cohort ([TREE 2016]; a follow-up study after PISA 2000) and TREE2 cohort ([TREE 2021]; a follow-up study after ÜGK 2016) indicates that, one year after leaving compulsory school, 90% (TREE) and 92% (TREE2) of those students who said they wanted to attend an academic track at the end of 9th Grade were actually attending an academic track.Footnote 6

Students are assigned a migrant background if at least one parent was born abroad. Consistent with previous studies, I classify students into the following minority groups (e.g., Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018): Swiss, Northwestern Europe (Germany, France, Austria, and Belgium), Southern Europe (Italy, Spain, and Portugal), the Balkans and Turkey, and other countries (all other countries). The grouping is based on the country of birth of the students and of their parents.Footnote 7 For 2006, no data were available that would allow a classification into migrant groups. Pupils whose parents are assigned different groups of origin (except for pupils with one Swiss-born parent)—for example, students with a French mother and a Turkish father—are assigned the minority group of the mother.Footnote 8

Furthermore, I differentiate the following migrant generations. Students are assigned to the first generation when they themselves and both of their parents were born abroad. If the students were born in Switzerland and both parents were born abroad, the students are assigned to the second migrant generation. If one parent was born abroad and one parent was born in Switzerland, the students are assigned to the 2.5 migrant generation. As there is no information about the countries of birth of the grandparents in the data, I cannot further differentiate the generations.

The following control variables, which have also been considered in other ethnic choice effects studies (e.g., Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017), were included in the analyses: lower secondary school track (basic requirements, extended requirements, academic track, and school without selection); age (in months); mean competence (weighted likelihood estimates) for the score in math and/or languages; social origin (highest parental ISEI); regional type of the municipality of the school (city, town, small town, or village); canton of residence; one Swiss-born parent (no/yes); and student born in Switzerland (no/yes).Footnote 9 See Table S2 in the Online Appendix for more information on the operationalization.

4.2 Analytical Sample and Missing Values

A total of 100,495 students participated in the surveys (excluding special needs students and students from schools without valid school weights). Of these students, 13.7% reported no valid response to the educational choice question.Footnote 10 This degree of missing information is consistent with findings from previous studies (Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017). The other model variables have the following missing value patterns: highest parental ISEI (2.5%), minority group (1.6%), regional type (1.4%), migration background (1%), age (0.2%), sex (0.1%), and competence scores (0.03%). Table 1 lists the case numbers separately by year, minority status, minority generation, and minority group. In addition, the numbers of all 9th-Grade students enrolled in Switzerland in the respective survey years are displayed. These figures show that the respective samples represent between 10 and 26.7% of the total number of 9th-Grade students in Switzerland.

5 Statistical Methods

As some variables in the data used show a substantial share of missing values, I replace the missing values in the dependent variable and the control variables with simulated values using multiple imputation (50 multiple imputed datasets per year; different imputations for models differentiated and undifferentiated by minority group; multiple imputation using predictive mean matching by 10 nearest neighbors; burn-in = 50). In addition to the model variables, the following auxiliary variables were included in the imputation models: home educational resources (PISA 52,53,54,55,2012); parental education; born in Switzerland; number of Swiss-born parents; student weights; and school weights.Footnote 11 All results presented in the paper are based on these imputed datasets.

In the first step of the analyses, the bivariate relationships between educational choices and minority status, minority group and minority generation are presented. These analyses show differences in educational choices between majority students and different minority groups, without considering different social backgrounds or academic achievement. In the second step of the analyses, regression models are calculated considering the control variables in order to present ethnic choice effects. To account for the cluttering of students in schools, I estimate multilevel models that include a random intercept for the schools and dummy variables for the cantons, as transition rates vary substantially across cantons.Footnote 12 As the dependent variable is a binary variable that does not represent a latent construct, I follow the recommendations of Breen et al. (2018) and estimate linear probability models. Separate regression models are calculated for the following comparisons: majority students versus minority students (undifferentiated by minority group); majority students versus minority students (differentiated by minority group); majority students versus students of different migrant generations (undifferentiated by minority group); and majority students versus students of different migrant generations (differentiated by minority group).

All analyses were performed using Stata 17 and some user-written ados (Jann 2007, 2014, 2018).

6 Bivariate Results

Figure 3 shows the proportion of students choosing the academic track over time by minority group. Comparing majority students with minority students shows that they opt for the academic track with similar frequency and that this pattern remains stable over time. When looking at minority groups, Swiss students aspire to the academic track more often than minority students from the Balkans and Turkey, but less often than minority students from Northwestern Europe and other countries. Students from Southern Europe have a slightly lower share of academic track choice than majority students. Except for students from other countries, there is a slightly positive trend toward more academic track choice over time.

Figure 4 shows the share of academic track choice over time by migrant generation and minority groups. When looking at the minority generations (undifferentiated by minority groups), there is a noticeable tendency for the academic track choice to increase in the cohort sequence and to converge with the patterns of the Swiss students. It is interesting to note that students from the 2.5 generation choose the academic track more often than majority students. When looking at the minority groups by generational status, clear differences emerge in patterns across the generational sequence. The group from Northwestern Europe shows higher academic track choice than the majority group in all generations. It is interesting to note that these shares tend to be highest in the second generation, and that a drop in rates from the second generation to the 2.5 generation can be observed. Students from minority groups that have a lower share of academic track choice than majority students (Balkans and Turkey and Southern Europe) tend to show an increase in academic track choice across generations. In these groups, academic track choice tends to be higher in the second generation than in the first generation.

Upper secondary academic track choices by minority group and minority generation, over time. Estimates based on m = 50 multiple imputed datasets; my own calculations. GER Germany, FRA France, AUT Austria, BEL Belgium, IT Italy, SP Spain, POR Portugal, TUR Turkey. (Source: PISA 2000–PISA 2012; ÜGK 2016)

7 Regression Results

Figure 5 depicts the ethnic choice effects for minority students, undifferentiated (top panel) and differentiated (bottom panel) by minority group. The regression tables (full model) are provided in the Online Appendix (see Table S3). Positive ethnic choice effects (majority versus minority students) can be found in Switzerland. This effect is very stable over time and does not decrease in magnitude: positive ethnic choice effects can be detected in every year studied.

Ethnic choice effects (academic track versus rest) over time, differentiated by minority group. Estimates based on m = 50 multiple imputed datasets; my own calculations. GER Germany, FRA France, AUT Austria, BEL Belgium, IT Italy, SP Spain, POR Portugal, TUR Turkey. (Source: PISA 2000–PISA 2012; ÜGK 2016)

Looking at the ethnic choice effects differentiated by minority groups, differences between the minority groups become apparent. For 2000, positive ethnic choice effects can only be found for students from the Balkans and from Turkey. In other years, positive ethnic choice effects can be found for all minority groups. For 2000–2012, the positive ethnic choice effects in the group of minority students from the Balkans and Turkey are larger than those for the groups from Northwestern Europe and Southern Europe. It should be noted, however, that the difference between the groups for 2003–2012 is only 2–3 percentage points. For 2016, there is no longer any difference between these groups.

Figure 6 depicts the ethnic choice effects for minority generations, undifferentiated (top panel) and differentiated (bottom panel) by minority group. It becomes apparent that the positive ethnic choice effects decrease in the generation sequence. This is particularly evident between the second generation and the 2.5 generation. For all minority generations—with the exception of the 2.5 generation in 2000 and 2006—statistically significant positive ethnic choice effects can be detected over time. These effects are very stable and do not diminish over time.

Ethnic choice effects (academic track versus rest) over time, differentiated by minority group and migrant generation. Estimates based on m = 50 multiple imputed datasets; my own calculations. GER Germany, FRA France, AUT Austria, BEL Belgium, IT Italy, SP Spain, POR Portugal, TUR Turkey. (Source: PISA 2000–PISA 2012; ÜGK 2016)

If we look at the individual minority groups differentiated by their generational status, the following points are noticeable. For minority students from Northwestern European countries, only a few statistically significant positive ethnic choice effects can be observed (first generation in 2012 and 2016; second generation in 2003 and 2016; second generation in 2009). No clear time trend can be identified for this group. Apart from 2000, positive ethnic choice effects for the group of Southern European minority students can be found for all years for the first and second generation. For the 2.5 generation, these effects can only be detected for 2016. For the group of minority students from the Balkans and Turkey, positive ethnic choice effects can be found for all years for the first and second migrant generations. For the 2.5 generation, no statistically significant positive effects are found for any of the years. For this group, too, the positive ethnic choice effects tend to decrease across succeeding generations (comparing the first, second, and 2.5 generation within one year). In general, positive ethnic choice effects decrease over the generations. However, a substantial shift of the generational effects over time cannot be detected.

8 Discussion

The aim of this descriptive paper has been to examine to what extent positive ethnic choice effects (across minority groups and minority generations) at the transition to upper secondary academic education represent a persistent empirical phenomenon in Switzerland (2000–2016). For this purpose, I used large-scale survey data (PISA 52,53,54,55,2012; and ÜGK 2016), which, owing to the large number of cases, has also enabled me to calculate subgroup analyses within minority groups across migrant generations.

In the first step of the analysis, I found persistent positive ethnic choice effects for minority students (in line with H 1). These results are in line with those of previous Swiss studies (Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018) and international studies (e.g., Jackson et al. 2012; Brinbaum and Guégnard 2013; Kilpi-Jakonen 2011; van de Werfhorst and van Tubergen 2007). Previous research has often focused on the analysis of a single transition cohort. The results of this paper go beyond those of previous research insofar as I have been able to show that these effects are demonstrable across multiple student cohorts (2000–2016). Positive ethnic choice effects (majority versus minority students) are persistent over time. This result is at odds with H 4, which suggests that positive ethnic choice effects should diminish over time. This persistence may be attributable to the fact that positive ethnic choice effects are statistical effects taking social origin into account, and thus changes in the composition of migrants (e.g., due to changes in immigration policies)—contrary to what I expected based on prior research—may not have a major influence on these effects.

In the second step of the analysis, I presented the results on ethnic choice effects differentiated by minority groups. The results show that—as theoretically expected—there are differences between the minority groups. In line with H 2, I have been able to demonstrate that the positive ethnic choice effects are largest for minority students from the Balkans and Turkey, followed by minority students from Southern Europe and Northwestern Europe. These findings are consistent with results of previous Swiss studies (Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018). Since this study, unlike previous studies, examines multiple cohorts of students, I have been able to show that, over time, the year 2000 in particular stands out as a special year. For 2000, only the group of minority students from Balkans and Turkey showed a positive ethnic choice effect, whereas in all other years positive ethnic choice effects can be detected for other minority groups as well. The results regarding the time effect support H 5 inasmuch as, over time (comparing 2000 and 2016), the group of minority students from the Balkans and Turkey lost its salient position and no further differences between the groups can be observed. In this context, however, it must also be made clear that the group differences for the years between 2003 and 2012 were only 2–3 percentage points.

In a third step of the analysis, ethnic choice effects were presented according to migrant generational status. As assumed in H 3, positive ethnic choice effects have been found to decline across generations. In particular, a more pronounced reduction of effects could be observed between the second generation and 2.5 generation. This could indicate that one parent born in Switzerland can support his or her child in building up country-specific human capital and provide him or her with information on the education system (Kilpi-Jakonen 2011). Furthermore, it is known from past research that the socioeconomic placement of parents in the generational sequence increases and that children in the generational sequence also have more country-specific human capital (Esser 2009, 2008; Drouhot and Nee 2019). This could contribute to the generational effects described above. Contrary to H 6, generational effects have been found to be stable over time. Theoretically, it was expected that, owing to the change in the composition of minority students (as a result of the change in immigration policies in the 1990s toward more highly skilled migrants), and owing to the change in the generational composition of minority students as a result of migration history (see Fig. 2), generational effects would decrease over time.

In a fourth step of the analysis, ethnic choice effects were presented differentiated by minority group and migrant generation. For the most part, this could not be reported in previous studies owing to the limited number of available cases. The subdivision of migrant generations by minority groups revealed some compelling results. I have found that ethnic choice effects are a persistent empirical phenomenon only for minority students whose parents were both born abroad (first and second generation). In particular, for students from the Balkans and Turkey, and Southern Europe, persistent positive ethnic choice effects are evident. However, for minority students whose parents were born in Northwestern Europe, no persistent positive ethnic choice effects have been observed. This could be because these parents speak at least one national language and that the school systems of these countries—depending on the language region of Switzerland—are very similar to the Swiss system. Furthermore, this group is better off in terms of parental occupational status than natives (see Fig. 1). In line with H 7, the ethnic choice patterns across migrant generations has been found to be quite stable over time for all minority groups.

Looking at minority students with one parent born in Switzerland (2.5 generation), positive ethnic choice effects were observed in some cases. However, the results do not indicate a persistent pattern, but rather that minority students with a Swiss-born parent barely differ from majority students in their decision regarding the upper secondary academic track. For this group, it could be argued that common explanatory patterns for positive ethnic choice effects might not be so explicative, because one parent has not migrated and so knows the education system (Kao and Tienda 1995; Forster and van de Werfhorst 2020). Hence, the results illustrate that it is not only important to distinguish between minority groups but also to differentiate within minority groups by generational status. Minority students whose parents both immigrated to Switzerland make more ambitious educational decisions than natives when they have the same academic abilities and parental resources. Minority students with one Swiss-born parent take very similar educational decisions at the transition to upper secondary academic education as natives, given the same academic abilities and parental resources. These results suggest that, from the 2.5 migrant generation (migrants with one Swiss-born and one foreign-born parent) onward, the educational choices made by minority students are similar to those made by natives for the minority groups investigated in this study. This convergence could result in less ambitious educational choices and hence lower dropout rates in upper secondary education for minority students (Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Tjaden and Hunkler 2017; Dollmann and Weißmann 2019).

One limitation of my study is that I have been unable to conduct a mediation analysis for the positive ethnic choice effects because of missing information in the datasets used. It has therefore not been possible for me to examine which theoretical mechanisms (e.g., immigrant optimism, information deficit, and blocked opportunities (Kao and Tienda 1995; Forster and van de Werfhorst 2020; Heath and Brinbaum 2007; Jackson et al. 2012; Dollmann 2017)) have the greatest explanatory power, and to what extent these vary between the minority groups and over time. Previous studies suggest that higher aspirations in particular can explain these positive ethnic choice effects (Dollmann 2017; Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Tjaden and Scharenberg 2017). Future research may help to clarify the reported generational differences. Furthermore, an intriguing question for future research is why these generational effects remain stable over time (contrary to my theoretical expectations). Another limitation of my study is that I have been unable to further differentiate the minority groups, for three reasons. First, there is no information on the birthplace of the grandparents in the dataset, so I could not further distinguish between migrant generations (Olczyk et al. 2014). Second, the dataset contains the very heterogeneous group of “other birth countries,” which cannot be further differentiated. However, from German research, we know, for example, that Southeast Asian minority students have especially ambitious educational aspirations (e.g., Nauck and Schnoor 2015). Third, even though I use large-scale data from a country with a high proportion of minority students and a large sample size relative to the student population (at least 10% of all enrolled 9th-Grade students), further differentiation—for example by gender (Fleischmann and Kristen 2014)—could lead to sample size problems. This suggests that even more sophisticated analyses of ethnic choice effects in the education system might need to focus on the use of administrative data (Wolter and Zumbuehl 2018; Gresch and Kristen 2011).

In summary, the results of this study suggest that positive ethnic choice effects in Switzerland are a persistent empirical phenomenon. This is particularly true for minority students from the Balkans, Turkey, Southern Europe, and other countries, whose parents were not born in Switzerland. Furthermore, minority students with a Swiss-born parent make very similar educational choices to those made by natives given the same academic abilities and parental resources. In the generational sequence, the educational decisions of minority students converge with those of natives. Hence, the results of this study suggest that more attention should be paid to generational status in research on ethnic choice effects.

Notes

For a more detailed description of Swiss immigration history, see Fibbi et al. (2015).

As the questionnaires in 2000 and 2003 only gave the option of selecting country of birth (France or Belgium), Belgium is included in this group, even though it is not a neighboring country from Northwestern Europe.

As no information on the country of birth of the grandparents is available in the data, I summarize those children who were themselves born in Switzerland and who also have one parent born in the country as the 2.5 generation.

Owing to data limitations, I am unable to conduct a mediation analysis on the explanatory power of these different mechanisms in this paper. I therefore focus on descriptively analyzing changes in ethnic choice effects over time.

For the exact classification of the different educational upper secondary programs, see Table S1 in the Online Appendix.

For majority students, these figures are 92% (TREE) and 93% (TREE2). For minority students, these figures are 87% (TREE) and 87% (TREE2).

In some studies, Italy is assigned to the group of Northwestern European countries. Such a classification does not substantially change the results shown below (see Figs. S1 and S2 in the Online Appendix).

The number of cases is too small for an analysis of this group alone, as this group accounts for only about 3% of the sample.

The variables “Swiss-born parent” and “student born in Switzerland” are used to generate the generational status for the analyses differentiated by minority generation.

It is interesting to note that relatively few “Do not know” answers were given, and that often the question was not answered at all (item nonresponse). This, and the fact that this question was often at the end of the last page of the questionnaire, might indicate that some of the students stopped answering the sometimes very lengthy questionnaire in an earlier section.

Simulation studies on biases in estimation results owing to missing values in the dependent variable arrive at different recommendations for imputations using auxiliary variables as to whether the imputed dependent variable should be used in the analyses or deleted (MID; von Hippel 2007; Sullivan et al. 2015). Figures S3 and S4 in the Online Appendix depict the results of the ethnic choice models using MID (N = 86,726). These results hardly differ from the results presented in the following pages.

Transfer rates to upper secondary academic education are significantly higher in French-speaking and Italian-speaking Switzerland than in German-speaking Switzerland (SCCRE 2018).

References

Allmendinger, Jutta. 1989. Educational systems and labor market outcomes. European Sociological Review 5:231–250.

Becker, Birgit, and Cornelia Gresch. 2016. Bildungsaspirationen in Familien mit Migrationshintergrund. In Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf: Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten, eds. Claudia Diehl, Christian Hunkler and Cornelia Kristen, 73–115. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

BfS (Bundesamt für Statistik). 2020. Ständige Wohnbevölkerung ab 15 Jahren nach Migrationsstatus und verschiedenen soziodemografischen Merkmalen, 2019. ID: su-d-01.05.03.01.01. Neuenburg: Bundesamt für Statistik.

BfS (Bundesamt für Statistik). 2022. Nach ausgewählten Nationalitäten: Ausbildungsstufen der ständigen Wohnbevölkerung und Erwerbstätigen nach Geschlecht. Neuenburg: Bundesamt für Statistik. je-d-03.02.00.04.01.03

Borgna, Camilla, and Dalit Contini. 2014. Migrant achievement penalties in Western Europe: Do educational systems matter? European Sociological Review 30:670–683.

Breen, Richard, Kristian Bernt Karlson and Anders Holm. 2018. Interpreting and understanding logits, probits, and other nonlinear probability models. Annual Review of Sociology 44:39–54.

Brinbaum, Yaël, and Hector Cebolla-Boado. 2007. The school careers of ethnic minority youth in France: Success or disillusion? Ethnicities 7:445–474.

Brinbaum, Yaël, and Christine Guégnard. 2013. Choices and enrollments in French secondary and higher education: Repercussions for second-generation immigrants. Comparative Education Review 57:481–502.

Buchmann, Marlis, Irene Kriesi, Maarten Koomen, Christian Imdorf and Ariane Basler. 2016. Differentiation in secondary education and inequality in educational opportunities: The case of Switzerland. In Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality—An International Comparison, eds. Hans-Peter Blossfeld, Sandra Buchholz, Jan Skopek and Moris Triventi, 111–128. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Cattaneo, Maria A., and Stefan C. Wolter. 2015. Better migrants, better PISA results: Findings from a natural experiment. IZA Journal of Migration 4:18.

Combet, Benita. 2019. The institutional dimension of class-based educational decision-making: Evidence from regional variation in Switzerland. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 48:301–320.

Contini, Dalit, and Davide Azzolini. 2016. Performance and decisions: Immigrant–native gaps in educational transitions in Italy. Journal of Applied Statistics 43:98–114.

Dollmann, Jörg. 2017. Positive choices for all? SES- and gender-specific premia of immigrants at educational transitions. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 49:20–31.

Dollmann, Jörg, and Markus Weißmann. 2019. The story after Immigrants’ ambitious educational choices: Real improvement or back to square one? European Sociological Review 36:32–47.

Drouhot, Lucas G., and Victor Nee. 2019. Assimilation and the second generation in Europe and America: Blending and segregating social dynamics between immigrants and natives. Annual Review of Sociology 45:177–199.

Engzell, Per. 2019. Aspiration squeeze: The struggle of children to positively selected immigrants. Sociology of Education 92:83–103.

Esser, Hartmut. 2008. Spracherwerb und Einreisealter: Die schwierigen Bedingungen der Bilingualität. In Migration und Integration, ed. Frank Kalter, 202–229. Sonderheft 48, Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Esser, Hartmut. 2009. Pluralisierung oder Assimilation? Effekte der multiplen Inklusion auf die Integration von Migranten. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 38:358–378.

Farago, Peter, Claude Hunold and Fredy Kuhn. 1996. Ausländische Erwerbstätige in der Schweiz: eine Strukturanalyse. Bern: Bundesamt für Statistik.

Fekjær, Silje N., and Gunn E. Birkelund. 2007. Does the ethnic composition of upper secondary schools influence educational achievement and attainment? A multilevel analysis of the Norwegian case. European Sociological Review 23:309–323.

Fibbi, Rosita, Ceren Topgül, Dusan Ugrina and Philippe Wanner. 2015. The new second generation in Switzerland: Youth of Turkish and former Yugoslav descent in Zurich and Basel. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Fleischmann, Fenella, and Cornelia Kristen. 2014. Gender inequalities in the education of the second generation in Western Countries. Sociology of Education 87:143–170.

Forster, Andrea G., and Herman G. van de Werfhorst. 2020. Navigating institutions: Parents’ knowledge of the educational system and students’ success in education. European Sociological Review 36:48–64.

Glauser, David. 2018. Same same but different. Migrationsspezifische Ungleichheiten beim Übergang in Ausbildungen der Sekundarstufe II in der Deutschschweiz. In Migration und Berufsbildung in der Schweiz, ed. Sonja Engelage, 158–189. Zürich: Seismo Verlag.

Gottfredson, Linda S. 1981. Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology 28:545–579.

Gresch, Cornelia, and Cornelia Kristen. 2011. Staatsbürgerschaft oder Migrationshintergrund? Ein Vergleich unterschiedlicher Operationalisierungsweisen am Beispiel der Bildungsbeteiligung. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 40:208–227.

Griga, Dorit. 2014. Participation in higher education of youths with a migrant background in Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Sociology 40:379–400.

Hagendoorn, Louk. 1995. Intergroup biases in multiple group systems: The perception of ethnic hierarchies. European Review of Social Psychology 6:199–228.

Heath, Anthony F. 2014. Unequal attainments: ethnic educational inequalities in ten Western countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heath, Anthony F., and Yaël Brinbaum. 2007. Guest editorial: Explaining ethnic inequalities in educational attainment. Ethnicities 7:291–304.

Heath, Anthony F., Catherine Rothon and Elina Kilpi. 2008. The second generation in Western Europe: Education, unemployment, and occupational attainment. Annual Review of Sociology 34:211–235.

Heckhausen, Jutta, and Martin J. Tomasik. 2002. Get an apprenticeship before school is out: How German adolescents adjust vocational aspirations when getting close to a developmental deadline. Journal of Vocational Behavior 60:199–219.

Jackson, Michelle, Jan O. Jonsson and Frida Rudolphi. 2012. Ethnic inequality in choice-driven education systems: A longitudinal study of performance and choice in England and Sweden. Sociology of Education 85:158–178.

Jann, Ben. 2007. Making regression tables simplified. The Stata Journal 7:227–244.

Jann, Ben. 2014. Plotting regression coefficients and other estimates. The Stata Journal 14:708–737.

Jann, Ben. 2018. Customizing Stata graphs made easy (part 1). The Stata Journal 18:491–502.

Jonsson, Jan O., and Frida Rudolphi. 2011. Weak performance—strong determination: School achievement and educational choice among children of immigrants in Sweden. European Sociological Review 27:487–508.

Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1995. Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly 76:1–19.

Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1998. Educational aspirations of minority youth. American Journal of Education 106:349–384.

Kilpi-Jakonen, Elina. 2011. Continuation to upper secondary education in Finland: Children of immigrants and the majority compared. Acta Sociologica 54:77–106.

Korber, Maïlys, and Daniel Oesch. 2019. Vocational versus general education: Employment and earnings over the life course in Switzerland. Advances in Life Course Research 40:1–13.

Kristen, Cornelia, and Jörg Dollmann. 2010. Sekundäre Effekte der ethnischen Herkunft: Kinder aus türkischen Familien am ersten Bildungsübergang. In Vom Kindergarten bis zur Hochschule: Die Generierung von ethnischen und sozialen Disparitäten in der Bildungsbiographie, eds. Birgit Becker and David Reimer, 117–144. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kristen, Cornelia, and Melanie Olczyk. 2013. Ethnische Einbettung und Bildungserfolg. In Bildungskontexte: Strukturelle Voraussetzungen und Ursachen ungleicher Bildungschancen, eds. Rolf Becker and Alexander Schulze, 353–403. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Kristen, Cornelia, David Reimer and Irena Kogan. 2008. Higher education entry of Turkish immigrant youth in Germany. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49:127–151.

Lancee, Bram. 2021. Ethnic discrimination in hiring: comparing groups across contexts. Results from a cross-national field experiment. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47:1181–1200.

McCluskey, Huguette, and Claudia Zahner. 2003. Das Projekt PISA und die Durchführung in der Schweiz. Tech. rep. Bern: Bundesamt für Statistik/Eidgenössische Konferenz der kantonalen Erziehungsdirektoren.

Meunier, Muriel. 2011. Immigration and student achievement: Evidence from Switzerland. Economics of Education Review 30:16–38.

Nauck, Bernhard, and Birger Schnoor. 2015. Against all odds? Bildungserfolg in vietnamesischen und türkischen Familien in Deutschland. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 67:633–657.

Nennstiel, Richard. 2021. Do more demanding lower secondary school certificates for minority students pay off? A comparison of VET access between Germany and German-speaking Switzerland. Soziale Welt 72:313–342.

Nennstiel, Richard. 2022. Explaining ethnic differences in access to VET in German-speaking Switzerland: The effects of application behavior and resources. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 50:396–414.

Olczyk, Melanie, Gisela Will and Cornelia Kristen. 2014. Immigrants in the NEPS: Identifying generation status and group of origin. Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, National Educational Panel Study, Bamberg, NEPS Working Paper No. 41a.

PISA, 2000. Huguette McCluskey-Cavin: PISA ch – Messung der Kompetenzen und Befragung der SchülerInnen in der Schweiz im 9. Schuljahr – 2000 [Dataset]. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2004. (Students) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-387-1 (Schools) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-388-1.

PISA, 2003. PISA.ch—Measurement of skills and survey of 9th year students in Switzerland—2003 [Dataset]. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2011. (Students) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-580-1 (Schools) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-581-1.

PISA, 2006. PISA.ch—Measurement of skills and survey of 9th year students in Switzerland—2006 [Dataset]. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2011. (Students) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-582-1 (Schools) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-583-1.

PISA, 2009. PISA.ch: Measurement of skills and survey of 9th year students in Switzerland—2009 [Dataset]. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2012. (Students) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-592-1 (Schools) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-593-1.

PISA, 2012. PISA.ch: Measurement of skills and survey of 9th year students in Switzerland—2012 [Dataset]. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2016. (Students) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-670-1 (Schools) https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-671-1.

Sacchi, Stefan, and Thomas Meyer. 2016. Übergangslösungen beim Eintritt in die Schweizer Berufsbildung: Brückenschlag oder Sackgasse? Swiss Journal of Sociology 42:8–40.

Salikutluk, Zerrin. 2016. Why do immigrant students aim high? Explaining the aspiration–achievement paradox of immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review 32:581–592.

SBFI, Staatssekretariat für Bildung, Forschung und Innovation. 2017. Lehrstellenbarometer April 2017. Tech. rep. Bern: Staatssekretariat für Bildung, Forschung und Innovation SBFI.

SCCRE. 2014. Swiss Education Report. Aarau: Swiss Coordination Centre for Research in Education.

SCCRE. 2018. Swiss Education Report. Aarau: Swiss Coordination Centre for Research in Education.

Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft. 2011. 7. Bericht des Observatoriums zum Freizügigkeitsabkommen Schweiz – EU. Auswirkungen der Personenfreizügigkeit auf den Schweizer Arbeitsmarkt. Bern: SECO – Direktion für Arbeit.

Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft. 2018. 14. Bericht des Observatoriums zum Freizügigkeitsabkommen Schweiz – EU. Auswirkungen der Personenfreizügigkeit auf Arbeitsmarkt und Sozialversicherungen. Bern: SECO – Direktion für Arbeit.

Spörlein, Christoph, and Cornelia Kristen. 2019. Why we should care about regional origins: Educational selectivity among refugees and labor migrants in Western Europe. Frontiers in Sociology 4:39.

Spörlein, Christoph, and Elmar Schlueter. 2018. How education systems shape cross-national ethnic inequality in math competence scores: Moving beyond mean differences. PLOS ONE 13:1–21.

Spörlein, Christoph, Cornelia Kristen, Regine Schmidt and Jörg Welker. 2020. Selectivity profiles of recently arrived refugees and labour migrants in Germany. Soziale Welt 71:54–89.

Sullivan, Thomas R., Amy B. Salter, Philip Ryan and Katherine J. Lee. 2015. Bias and precision of the “multiple imputation, then deletion” method for dealing with missing outcome data. American Journal of Epidemiology 182:528–534.

Tjaden, Jasper Dag. 2017. Migrant background and access to vocational education in Germany: Self-selection, discrimination, or both? Zeitschrift für Soziologie 46:107–123.

Tjaden, Jasper Dag, and Christian Hunkler. 2017. The optimism trap: Migrants’ educational choices in stratified education systems. Social Science Research 67:213–228.

Tjaden, Jasper Dag, and Katja Scharenberg. 2017. Ethnic choice effects at the transition into upper-secondary education in Switzerland. Acta Sociologica 60:309–324.

TREE, 2016. Transitions from Education to Employment, Cohort 1 (TREE) [Dataset]. University of Bern. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne. https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-816-7

TREE, 2021. Transitions from Education to Employment, Cohort 2 (TREE2), Panel waves 0–2 (2016–2018) [Dataset]. University of Bern. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne. https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-1255-1.

ÜGK, 2016. Christian Nidegger: ÜGK/COFO/VECOF 2016: Competencies of Swiss pupils in mathematics [Dataset]. Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2019. https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-1004-1.

Veerman, Gert-Jan Martijn, and Jaap Dronkers. 2016. Ethnic composition and school performance in the secondary education of Turkish migrant students in seven countries and 19 European educational systems. International Migration Review 50:537–567.

Verner, Martin, and Laura Helbling. 2019. Sampling ÜGK 2016. Technischer Bericht zu Stichprobendesign, Gewichtung und Varianzschätzung bei der Überprüfung des Erreichens der Grundkompetenzen 2016. Zürich: Institut für Bildungsevaluation, Universität Zürich.

Von Hippel, Paul T. 2007. Regression with missing ys: an improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data. Sociological Methodology 37: 83–117.

Werfhorst, Herman G. van de, and Frank Van Tubergen. 2007. Ethnicity, schooling, and merit in the Netherlands. Ethnicities 7:416–444.

Wolter, Stefan C., and Maria Zumbuehl. 2018. The native-migrant gap in the progression into and through upper-secondary education. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 6810.

Zschirnt, Eva. 2019. Equal outcomes, but different treatment—subtle discrimination in email responses. From a correspondence test in Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Sociology 45:143–160.

Zschirnt, Eva. 2020. Evidence of hiring discrimination against the second generation: Results from a correspondence test in the Swiss labour market. Journal of International Migration and Integration 21:563–585.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments on earlier drafts, I wish to thank David Glauser, Rolf Becker, the editors of the journal, and the two anonymous reviewers.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

R. Nennstiel declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Online Appendix: https://kzfss.uni-koeln.de/sites/kzfss/pdf/Nennstiel.pdf

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article