Abstract

States have increasingly started to terminate and renegotiate their bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Dominant explanations have however overlooked the underlying bargaining dynamic of investment treaty negotiations. This paper argues that while states initially in a weaker negotiating position have the strongest incentives to change their existing BITs, their ability to do so is constrained by their bargaining power. Such states become more likely to demand renegotiation or exit dissatisfying BITs if they have experienced sufficient changes in their bargaining power in relation to the treaty partner. This paper identifies observable implications of the weaker states’ incentives and bargaining power constraints for adjusting their bilateral investment treaty commitments. Leveraging a panel dataset on 2,623 BITs ranging from 1962 to 2019, interaction effects between bargaining power and incentives stemming from rationalist and bounded rationality assumptions about states’ decision-making are analyzed in relation to the occurrence of renegotiations and terminations. The paper finds that change in bargaining power in relation to the treaty partner is an important factor underlying the weaker states’ ability to terminate or renegotiate BITs, contributing to the study of investment regime reform and exit from international institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

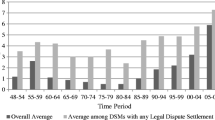

The most prominent institutional architecture to regulate international investment today consists of a web of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) practice enabled by them (Bonnitcha et al., 2017). In recent years, the international governance regime has increasingly seen states terminating and renegotiating their investment treaties (Fig. 1.) Dominant explanations for the shift argue that the increasingly controversial practice of ISDS is driving the current change: the practice enables foreign investors to bring lawsuits against their host governments in international tribunals and claim compensation when they feel the host has violated the terms of the treaty, turning governments against them (Waibel, 2010; Haftel & Thompson, 2018; Thompson et al., 2019).

While such disputes were initially thought to mainly arise in situations of direct expropriation such as nationalization, modern ISDS mostly addresses so-called cases of indirect appropriation. There are increasing concerns that investors employ ISDS not only when the host government is intentionally infringing their property rights, but when damage is done to their investments as a by-product of other regulatory efforts, or even strategically to deter unfavorable future policies (Wellhausen, 2016; Pelc, 2017; Johns et al., 2020; Moehlecke, 2020). For example, Argentina became the target of many ISDS-challenges due to its efforts to manage the financial crisis of early-2000s: currency devaluation and other emergency measures hit foreign investors with severe financial losses who responded through legal means.

The declining number of new BITs and the simultaneously increasing ISDS cases have led many to observe that the investment regime is currently undergoing a “backlash” against the dispute settlement mechanism, akin to wider challenges to globalization, international organizations, and liberal international order (Lake et al., 2021; Walter, 2021). Governments are increasingly pursuing efforts towards greater state regulatory space (Broude et al., 2017) by terminating, renegotiating, replacing BITs with investment provisions in new preferential trade agreements (PTAs), or even adopting alternative domestic legal arrangements (Berge & St John, 2021).

Yet, many states have not taken action to reform their BIT-commitments, while others have only done so selectively. Why do some states keep their investment treaties even when faced with the risks of ISDS? What explains the variation in governments’ reform efforts regarding their BITs? The current emphasis on ISDS as an explanation for driving change in the investment treaty regime is overlooking structural dynamics that are well-established in the literature on international cooperation and negotiations. A largely overlooked constraint on government action can help to address this puzzle – the bargaining power dynamic between treaty partners.

The weaker parties in BIT relations tend to be disadvantaged in investment arbitration, and therefore have the strongest incentives to overhaul the existing investment treaties (Schultz & Dupont, 2014; Behn et al., 2017). Especially developing countries are the most frequent respondent states in ISDS cases, while developed Western countries such as the USA, the Netherlands, and the UK are the most frequent home states of claimants (UNCTAD, 2020b). However, developing countries often find their options for BIT reform severely limited. Unless an improvement in their bargaining power has taken place since treaty signature – largely determined by relative economic power – these states are unlikely to have the leverage to push for change in the terms of investment governance with their stronger counter parts. States that were initially in a weaker bargaining power position in relation to their treaty partners therefore continue to be constrained by their weaker bargaining power position in the BIT regime.

Economic power translates into bargaining power in investment treaty negotiations by improving concrete alternatives to the existing agreements, and generating confidence that such better outside options are realistically achievable in the future (Fisher & Ury, 1981; Lax & Sebenius, 1985). Once in place, any state wishing to escape international investment treaties must weigh their options considering the existing treaty. If a state’s relative economic position has improved since signing of the BIT, it is more likely to develop a credible exit threat through improved alternatives, and therefore becomes able to demand renegotiation of the agreement or else withdraw from it.

Due to the asymmetric origins of the BIT regime, the treaties disproportionately favor the initially stronger partner states, who were able to push for their favored features in the treaties (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010; Alschner & Skougarevskiy, 2016). Although there are various incentives that may drive stronger states to want to adjust their BITs, such as desires to modernize their terms, their ability to demand reform will not depend on changes in their bargaining power because of their already stronger position at the time of treaty signing. On the other hand, the initially weaker states will benefit from a closing of the relative economic gap. They become more likely to act on any reform incentives following improvement in their bargaining power.

The incentives for the weaker states driving change in BITs are likely to differ depending on the reasons for which they initially signed them. States who joined for boundedly rational reasons are likely to learn about the risks of BITs after facing ISDS-cases and therefore change their minds about BITs (Poulsen & Aisbett, 2013). On the other hand, states who adhered more to the assumptions of rationalist logic and perceived BITs as a tool to attract more investment are likely to initiate reform following changes that attract FDI independent of the legal protections provided by BITs: economic growth and improved law and order can provide incentives for such states to reform BITs. The initially weaker states are, however, only likely to act upon these incentives if the constraint of bargaining power enables their reform efforts.

The theory is supported with evidence from a panel dataset on BITs with data on the timing of their signature, renegotiation, and termination. The findings suggest that the effect of the weaker party facing ISDS cases on BIT termination and renegotiation is conditional on whether there has been a substantial change in the relative economic power between the treaty partners. Results from various models illustrate that the more the initially weaker party to the BIT has caught up with the stronger party, the larger the effect of an additional ISDS case as respondent is on the probability of BIT reform. Furthermore, economic growth and improved law and order in the initially weaker country have a greater positive effect on the likelihood that the BIT gets unilaterally terminated or renegotiated if the two signatory states have decreased their economic power difference.

The main contributions of the paper are twofold. While the consideration of states power, competition, and negotiation dynamics have been at the center of explaining initial emergence and design of BIT (Guzman, 1998; Elkins et al., 2006; Allee & Peinhardt, 2010, 2014), a similar framework has not been employed to explain recent developments in the investment treaty regime. This paper contributes to the empirical research on change in international regimes by showing that a background factor of international bargaining power influences the outcomes of BITs for states that face the strongest incentives for overhauling the current system for investment governance.

Furthermore, the investment treaty regime provides an interesting context in which to study which actors exit from international agreements and why. It contributes to the emerging literature on states’ exit from international organizations (Gray, 2018; von Borzyskowski & Vabulas, 2019) by highlighting that decisions to sign, renegotiate, or terminate international agreements always involve strategic considerations, even amidst the potential dynamics of backlash against globalization.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. First, it outlines the asymmetric origins of BITs and how trends in ISDS have been described to catalyze changes in the regime. Second, the theory about constraints and incentives of the weaker states surrounding the investment treaty reform is presented along with testable hypotheses. Third, a quantitative study using a panel dataset on BITs is presented, along with measures for bargaining power and different incentives. Fourth, results of empirical analysis focusing on interaction effects between constraints and incentives in predicting deviation from an existing BIT are presented. The final section concludes.

1.1 The origins of BITs and their reform

1.1.1 Decision to sign

From the very first investment treaty between Germany and Pakistan in 1959, BITs were meant to protect the interests of foreign investors abroad, and therefore, enhance foreign direct investment (FDI) into states which otherwise may have been left without benefits of this specific form of economic cooperation. In particular, developing countries hoped to attract badly needed capital by signing BITs with major capital exporters during the economic downturn of the 1980 and 1990 s, which was also a time of stagnant international bank lending (Simmons, 2014).

Two broad strands of research on the origins of the BIT-regime adopt different assumptions about the decision-making processes of states when first signing BITs. Adopting some of the rationalist and unitary-state assumptions, international relations literature has theorized of BITs as instruments for addressing cooperation problems surrounding international investment (Abbott & Snidal, 1998; Koremenos et al., 2003; Koremenos, 2005). In particular, the rational design paradigm has considered the strong dispute settlement features a prime example of an enforcement mechanism for continued international cooperation, or an escape clause allowing temporary deviation from treaty obligations but preserving long term cooperation (Rosendorff & Milner, 2001; Allee & Elsig, 2016). BITs have been theorized to provide host states a credible commitment device to “tie their hands” regarding fair treatment of foreign investors, and BITs could lead to the race-to-the-bottom dynamic amongst developing countries competing for foreign capital (Salacuse, 1990, 2017; Guzman, 1998; Salacuse & Sullivan, 2005; Elkins et al., 2006; Tobin & Rose-Ackerman, 2011).

On the other hand, the bounded rationality perspective asserts that real-world leaders are likely to resort to mental short-cuts optimizing time and effort, and therefore likely to fall into cognitive biases in their decision-making (Poulsen, 2015). BITs were, according to this logic, not a classically rational choice by states, but merely a boundedly rational one – perhaps due to their status as focal points for arranging governance of investments (Poulsen, 2020). While rationalist states in a world of complete information could be expected to accept ISDS as a fundamental part of how BITs work and enhance credible commitments, and even anticipate the occasional arbitration with foreign investors, boundedly rational states might be more likely to turn against BITs after facing disputes with investors. ISDS can provide a vital learning mechanism regarding the true risks BITs entail (Poulsen & Aisbett, 2013).

Decisions to sign, keep, or reform BITs are also often influenced by non-economic considerations. States may be more motivated to sign economic agreements with foreign policy and military allies (Powers, 2004; Long & Leeds, 2006), or with countries that have good reputations (Gray, 2013; Gray & Hicks, 2014). There may also be ideological reasons for which states choose to cooperate with certain partners over others, with some states willing to sign and maintain agreements with autocrats or populists (Debre, 2022, 2021b; Voeten, 2021). Furthermore, various domestic political dynamics have been found to influence BIT signing, such as attempts to signal competence to domestic audiences in the face of a civil conflict (Billing & Lugg, 2019), or to enhance leadership survival in autocracies (Arias et al., 2018). Despite BITs continuing to be highly technical instruments, decisions regarding them are fundamentally political beyond their international legal and economic purposes.

1.1.2 Investment dispute settlement and “backlash”

In 2017, the lowest number of BITs were negotiated since 1983 and the number of terminations exceeded new agreements for the first time (UNCTAD, 2018, p. 88). Because BIT terminations and renegotiations closely follow the trend of accumulating ISDS disputes, many have accepted that increasing instance of investment arbitration is driving BIT reform efforts (Fig. 2.)

However, many states have not pursued reform of their BITs despite facing ISDS cases. Although Argentina has been a respondent in the largest number of ISDS disputes, 62 reported by UNCTAD, it has not terminated any of its BITs, and only renegotiated one.Footnote 1 Likewise, when Ecuador decided to take radical action in response to accumulating legal challenges based on its investment treaties, it unilaterally denounced many BITs between 2008 and 2010. However, at the time, it decided to keep some of the treaties that had resulted in legal disputes, most notably the BIT with the United States. States have therefore been selective in their efforts to reform BITs, with greater caution paid regarding BITs with important economic partners.Footnote 2 Given the explanatory power attributed to ISDS experience in the current literature, it is remarkable that most states that have faced ISDS have not terminated any BITs, while some states have terminated and renegotiated treaties despite none, or relatively few arbitration cases faced.

1.1.3 Strategies for changing BITs

When a state wants to pursue changing the terms of its BITs, it has several strategies at its disposal. First, it can exit the agreement by conducting unilateral termination according to the provisions of the BIT in question. The downside is that while this dissolves any obligations towards new investors under the treaty, unilateral termination triggers the so-called sunset clause, ensuring that the terms of the treaty stay in force for investments made prior to termination usually between 10 and 15 years afterwards (Harrison, 2012).

More importantly, unilateral termination of BITs can also signal to foreign investors an unwillingness to guarantee their protections in the future. Foreign investors often rely on cues regarding the investment climate and credit worthiness of target countries (Brooks et al., 2015; Kerner & Pelc, 2022; Shim, forthcoming). Signing BITs can be thought of as having provided a signal to investors lacking adequate information about the investment conditions in prospective host countries, because the risk of ISDS is greater in countries with bad investment climates (Tobin & Rose-Ackerman, 2011). Exit from BITs, in turn, can be interpreted by investors as preparation to limit exposure to investment arbitration, and therefore increase uncertainty over the government’s intentions regarding investment regulation, potentially discouraging investment.Footnote 3

Unilateral termination of BITs can also send a hostile signal to the partner state, who might interpret the exit as defection from a cooperative equilibrium, damaging the reputation of the state as a reliable partner in international cooperation (Axelrod, 1984; Axelrod & Keohane, 1985; Oye, 1986). Furthermore, the unilateral withdrawal from BITs and ISDS arbitration centers such as the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) became adopted by left-wing governments in Latin America through the 2000s (Calvert, 2018a). Any other states also considering taking unilateral action regarding BITs risk becoming associated with such governments, which used harsh rhetoric against the investment treaty regime, ISDS, and multinational companies (Gray, 2013). Concerns over hostile signalling through unilateral BIT terminations are therefore a serious cost of pursuing the strategy.

Given the costs on unilateral termination, states can attempt to reach an agreement with their bilateral partner to adjust the terms of the BIT. They can renegotiate or amend the existing BIT, negotiate a new replacing agreement, or mutually agree to terminate it.Footnote 4 However, initiating any adjustments to BITs can be challenging especially for the initially weaker parties. If the initially stronger state continues to benefit from the agreement, it has little incentive to re-open BIT negotiations, or mutually terminate it.Footnote 5 Especially the traditionally major capital exporters tend to prefer to keep their investment protections unchanged with developing country partners, at least until an alternative instrument can be drafted and proposed at their own initiative.Footnote 6

Any adjustment of existing BITs requires the treaty signatory states to reach an agreement, and therefore, they face the same challenges as renegotiation: as long as one state continues to prefer keeping the old provisions in place, renegotiation or mutual termination are unrealistic options especially for the initially weaker states seeking BIT reform. Often, unilateral termination of the BIT is the only realistic strategy available for the initially weaker states.

2 Why some states terminate and renegotiate BITs while others do not?

2.1 Bargaining power constraints

BITs are fundamentally shaped by the underlying asymmetric negotiations. Crucially, the state with stronger bargaining power in relation to the opponent shapes the treaty to more closely resemble its preferences, while the weaker party in negotiations is largely a rule-taker (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010, 2014; Alschner & Skougarevskiy, 2016). At the onset of the BIT regime, the treaties in protection of foreign investments were designed by powerful, capital exporting states. European countries, and later the United States, were leading the way in designing legal protections for investors, often in regions of political instability.Footnote 7 This asymmetry resulted in expansive protections for foreign investors from the powerful, largely capital exporting states, such as the strong ISDS-mechanism, sunset clauses ensuring treaty protections long after possible treaty termination, and vague definitions of investments and investor nationality.

If these underlying asymmetric power relations change, we should also expect a change in BITs themselves. Recent years have seen an increasing importance of new actors in the global economy. China as well as other emerging economies have increasingly taken an active role in economic negotiations for the first time, with states such as India, Indonesia, South Africa among those who have unilaterally terminated large numbers of their BITs.Footnote 8 It is likely that as such states undergo substantive changes in their economies and also begin to export more capital, they become more interested in actively shaping their rules of investment governance (Haftel et al., 2021).

We should expect changes in the economic power dynamic to result in changes in BITs because economic power translates into bargaining power in investment treaty negotiations. Economic power improves concrete alternatives to the existing agreements and generates confidence that better outside options are realistically achievable in the future. Economically stronger states tend to enjoy greater opportunities in the global economy. Foreign investors are particularly interested in investing in developing countries with large economies in pursuit of larger returns for their investments, and hence their governments are also motivated to sign BITs with them (Chakrabarti, 2001; Neumayer, 2006). All else equal, negotiating an economic agreement with an economically powerful partner is considered a promising opportunity for any government, leading fast growth economies to become attractive as new economic partners. It is therefore the greater access to such potentially improved alternatives for investment and economic partners that translates economic power into bargaining power (Fisher & Ury, 1981; Lax & Sebenius, 1985).

States’ bargaining power in international negotiations can also stem from various different sources. Domestic audiences can effectively limit the extent to which compromises can be made, narrowing the bargaining window available at the international level (Putnam, 1988). Because the options available regarding international negotiations may shift depending on what is ratifiable domestically, state leadership as well as coalitions that provide them with political power can also shape the bargaining power of a government (Mattes et al., 2016). State capacity and bureaucratic quality of governments can also strongly shape negotiation outcomes, especially with regards to BITs (Berge & Stiansen, 2016; Berge, 2021). The opportunities for improving bargaining power might also vary depending on the institutional bargaining environment (Schneider, 2011). Such differing sources of power in negotiations can make for different international bargaining outcomes. However, given the extent to which global economic asymmetries have shaped the BIT regime, it is precisely changes in the economic power symmetries that are likely account for the largest shifts in bargaining power dynamics in the aggregate.

When a state experiences an improvement in its economic power, its existing agreements need to continue to be favorable in comparison to the new potential alternatives brought by economic improvement. If a state views the terms of the existing BITs as worse than could be achieved through outside options, it develops a credible exit threat – a possibility that unless the terms of cooperation are adjusted to meet its preferences, the dissatisfied party will exit from the agreement (Bergès & Chambolle, 2009; Slapin, 2009). In practice, change in the relative economic power over time between signatory states is effective in creating a credible exit threat, because especially the stronger states are most likely to observe improvement in the weaker states bargaining power when they catch up with them economically.

Development of exit threat by a signatory state makes both unilateral termination and renegotiation of BITs more likely. For unilateral termination, the state needs to believe that it is better-off without the BIT in place, a possibility that increases in likelihood the stronger its perceived alternatives become. Likewise, renegotiation becomes more likely if the partner state becomes aware of the emerging exit threat and is willing to accommodate the new demands to preserve the cooperative agreement. However, the change in bargaining power alone is unlikely to be sufficient in explaining whether renegotiation or unilateral termination of a BIT is the likely outcome. In empirical testing, whether bargaining power is a determinant of both terminations and renegotiations is investigated separately. Furthermore, some of the possible factors which might make unilateral termination more likely over successful renegotiation are also explored.

Although both signatory states might want to push for change in BITs, it is primarily the initially weaker party that becomes more likely to initiate reform of their BITs following an improvement in its bargaining power. Because the initially stronger parties were already able to demand changes in existing agreements or else walk away from them, their ability to initiate changes in investment treaties is not dependent on further improvement in their bargaining power, like that of their weaker counter parts. One would therefore expect the initially weaker states to be more responsive to changes in the underlying bargaining power dynamic.

The bargaining power dynamic influences states’ decisions regarding BITs regardless of the reasons for which they signed BITs in the first place: once in place, there are consequences if agreed-on obligations are abandoned, and states must consider the associated costs and benefits. Afterall, it is a different matter to deviate from an established agreement than it is to join one in the first place (Mossallam, 2015). Bargaining power change can therefore explain when an initially weaker state is able to initiate change in their treaties by lifting some of the constraints on the government’s decision-making. Next, states’ incentives for BIT reform beyond bargaining power are outlined.

2.2 States’ incentives for reform

While the reasons for why individual governments seek reform in their international agreements vary, it is possible to identify common incentives across states. Although many states have begun to recognize the need for rethinking investment governance, it has been primarily developing and emerging economies that have taken the lead in BIT termination and renegotiation (UNCTAD, 2020a). This is because the primary concern of developed countries continues to be the provision of protections for their investors in host countries (Neumayer, 2006), and they continue to enjoy the benefits from BITs they negotiated in a stronger bargaining position. Developed countries have so far initiated multilateral discussions toward adjusting the terms of investment agreements amongst themselves and have therefore been less likely to push for reform in individual BITs especially with developing country partners.

2.2.1 Initially weaker states’ incentives

Factors that incentivize weaker states to change their BITs are likely to differ depending on whether they signed them as a result of a rationalist cost-benefit analysis, or because of boundedly rational decision-making. If the decision to sign BITs initially was made based on mental short-cuts, ISDS-cases can generate learning effects that break the bounded rationality underlying the agreement. Once governments become targets of ISDS lawsuits, the underlying boundedly rational logic of BITs becomes questioned: instead of defaulting to the old cognitive biases, increased efforts are made to carefully consider the costs and benefits of the BIT. This dynamic can explain the lack of enthusiasm towards signing more investment treaties since the legal disputes have started to accumulate (Poulsen & Aisbett, 2013). Experienced ISDS cases as respondent are therefore likely to form the strongest incentive driving their decision to terminate or renegotiate old BITs.Footnote 9

How exactly weaker states will want to adjust their BITs in response to learning through ISDS is however not obvious. States have been found to pursue larger state regulatory space in BITs as a result of ISDS experience (Thompson et al., 2019), and others have increased the precision of their legal language (Manger & Peinhardt, 2017). However, some initially weaker states might be willing to accept stronger investor protections due to their shifting status from mostly capital recipient towards a sender of FDI (Haftel et al., 2021). Regardless of exactly what kind of change is pursued, experiencing ISDS is likely to initiate a review and re-consideration of the old investment instruments, and hence increase the likelihood of change in them.

Because the initially weaker states’ BIT policies are likely to be constrained by their bargaining power in relation to the partner state, the effect of learning through ISDS on BIT outcomes will likely be conditional on bargaining power change. When the two parties have approached each other in their relative economic power, it is expected to empower the initially weaker state and make them able to act upon their reform incentives. It is therefore likely that if the economic gap between the parties has decreased, the chance of BIT reform also increases when interacted with the initially weaker party’s ISDS experience.

H1: BIT is increasingly likely to get terminated or renegotiated when the initially weaker signatory state has faced ISDS cases and the relative economic power difference has decreased since treaty signature.

There are distinct incentives that are likely to drive the behavior of states that initially signed BITs according to rationalist assumptions to attract FDI. They can develop other means to appear attractive to investors, and hence make old BITs futile in this task: high economic growth may result in an ability to attract investors regardless of whether or not the state is a signatory to BITs.Footnote 10 Additionally, improved law and order domestically may serve the same purpose as BITs to secure property rights of foreign investors, decreasing uncertainty and investment risk, and therefore making the treaties futile and unnecessarily risky.

Like the incentives emerging in response to facing ISDS, the bargaining power constraints however influence whether the emergence of these incentives can be acted upon by the initially weaker states. Interaction effects between factors that capture these incentives and bargaining power change are therefore expected to correspond to higher likelihood of change in the old BIT.

Hypothesis 2

BIT is increasingly likely to get terminated or renegotiated when the weaker signatory state has experienced high economic growth and the relative economic power difference between signatory states has decreased since treaty signature.

Hypothesis 3

BIT is increasingly likely to get terminated or renegotiated when the weaker signatory state has improved its law and order and the relative economic power difference between signatory states has decreased since treaty signature.

2.2.2 Initially stronger states’ incentives

In contrast to the weaker states, the stronger parties are less likely to face incentives to renegotiate or terminate BITs, as their investors continue to enjoy the protections provided in them. Stronger states are unlikely to develop incentives for reform in light of improvements in economic conditions like their weaker counterparts; however, they may also become incentivized to adjust BITs in response to ISDS cases. Concerns that regulation of investments for the protection of the environment or public health may result in international arbitration have become increasingly pressing also in developed countries.Footnote 11

Stronger states may therefore also recognize the need to update or make treaty terms more precise considering new regulatory needs, especially if the domestic political opinion favors stronger regulation of foreign investment. However, it has so-far manifested mostly in discussions over investment agreements amongst Western developed states, such as the Transatlantic Trade and Partnership Agreement (TTIP) (Hamilton and Pelkmans, 2015), and the decisions at the EU-level to eventually fade out all intra-EU BITs. In the past, states have attempted to keep their investment treaty commitments relatively consistent with each other, making use of model templates when negotiating their BITs (Berge & Stiansen, 2016; Allee & Elsig, 2019). Therefore, if the investment rules amongst developed countries get adjusted, the initially stronger states might also become eventually inclined to adjust their BITs with others for greater consistency.

3 Data and methods

The employed dataset is based on the UNCTAD International Investment Agreements Navigator, which includes information on the timing of termination and renegotiation of BITs.Footnote 12 The unit of analysis is the individual treaty-year, embedded in country dyads: for example, both the Indonesia-Netherlands BIT (1968) and the Indonesia-Netherlands BIT (1994) are included as separate treaties in the dataset, belonging in the same Indonesia-Netherlands-dyad. The treaties have observations from the year the BIT entered into force until the year it gets terminated or renegotiated, or until 2019 in case the BIT does not experience either event.

The data structure has two main advantages. It enables the identification of the unique negotiation year of the treaty, which is leveraged for constructing the measure capturing bargaining power change. Furthermore, the data structure allows the employment of BIT fixed effects in modelling, isolating the effects of interest from any treaty-specific features. The dataset includes 2,623 unique BITs within 2,481 dyads, and a total of 51,702 treaty-years ranging from 1962 to 2019. Because the theorized bargaining power dynamic is only expected to explain outcomes of BITs that have the power of international law, only BITs that have entered into force are included.Footnote 13

To capture the bargaining power dynamic between BIT signatory states, two strategies are adopted. First, the signatory states are ordered according to which one was likely the stronger party in the BIT negotiations initially. Following the literature on the power-dynamics at the onset of the BIT-regime, the primary coding rule identifies the state with a larger volume of FDI exports in the year of BIT signature as the stronger party.Footnote 14 However, to account for the access to and power of technical knowledge and expertise in economic negotiations, if the party with smaller exports was a member of the OECD, the OECD member is coded as stronger. 90% of the dyads can be ordered according to these two rules. To include additional dyads, especially with developing countries for which export data is limited, two additional coding rules are employed: if one of the states was a member state of the EU in the year of BIT signature while the other was not, it is coded as the stronger party. If the dyad cannot be ordered by these rules, the party with higher gross domestic product (GDP) in the year of signature is coded as stronger.

Second, change in bargaining power, the main variable capturing constraints, is measured employing GDP data only. This is because GDP data has the best coverage both in the timeseries as well as the cross section, and therefore results in a sufficient coverage for the variable. Measure Relative power change therefore captures the difference between the parties’ logged GDP compared to what it was in the year of BIT signature (Eq. 1). Negative values correspond to a decreased economic gap between the parties.Footnote 15

The measure is not suitable in assessing bargaining power change in situations where one party overtook the other in terms of economic power, a situation concerning a small subset of treaty-years (1,061 out of 51,702).Footnote 16 These instances are not included in the main Relative power change variable, but they are noted separately with a binary variable Overtook, which captures if a state had a lower GDP in the year of BIT signature but a larger GDP in the year of observation than the partner state.

The main outcome variable Deviation is binary, capturing whether the BIT is renegotiated, amended, unilaterally terminated, or terminated by consent. When incentives align with the lifting of bargaining power constraints, the BIT is expected to deviate from staying in force, whether through renegotiation or unilateral termination.Footnote 17 To investigate possibly differing attributes of Unilateral termination and Renegotiation, their occurrence is also captured by respective binary variables.

To measure the theorized incentives for each signatory state, ISDS respondent cum. measures the number of cumulative ISDS cases brought against the states separately. I include ISDS cases based on BITs as well as other instruments, as legal challenges by foreign investors are likely to change states’ incentives regardless of which instrument was used to bring the suit. It is also possible that states learn from other countries’ ISDS experiences as well as their own, possibility accounted for by year fixed effects. As a robustness check, I also investigate the effect of each state having faced any ISDS cases, captured by a binary variable ISDS respondent any. Although governments are unlikely to initiate BIT reform following cases where they were home states because governments are rarely involved in disputes their companies initiate, I also test for any possibile learning effects with the variable ISDS home cum, measuring cumulative cases as home state respectively for each signatory state. Economic Growth is captured by the annual GDP percent growth rate measure from World Development Indicators, and Law and Order variable comes from the PRS Group’s researcher dataset, where it is measured in 6-point scale with higher values capturing more positive conditions from the perspective of potential foreign investors (PRS Group, 2020).

3.1 Additional attributes of BITs outcomes

To account for other possible factors driving BIT-policy decisions, a set of control variables are included. Because the amount of FDI a government exports may influence its willingness to change investment treaties, variable FDI outflows is included to measure the volume of FDI exported by the government as a percentage of its GDP. Although the developments concerning intra-EU BITs are recent, it is possible that some of the latest terminations in the dataset result from them. I therefore control for Intra-EU, which is coded 1 if both of the parties are EU members.

Change in the political regime might make leaders more receptive to citizens’ demands, and it is captured by variable Democratization, which is a binary variable taking the value 1 the state has experienced an increase in their democracy score of 3 or more the past three years.Footnote 18 Likewise, because governments which are sensitive to citizens’ and NGOs’ activism and any opposition to ISDS practice are more likely to initiate reform of BITs, Democratic accountability captures higher accountability with increasing values on a six-point scale from the PRS researcher dataset. Further, the Socioeconomic conditions in each partner state are measured by a variable on a 12-point scale, higher values indicating stronger conditions, because overall living conditions in a country may be associated with more vocal participation in the policy-making processes and hence influence elite decision-making.

Changes in state leadership can also create incentives for new leaders to abandon foreign policies of their successors, and shifts in domestic supporting coalitions can also influence economic and foreign policy decision-making (Mattes et al., 2016). I therefore control for changes in the ruling government, which might induce policy changes in BITs with variable Leader transition, coded as 1 if there is at least one leadership transition in a given year and 0 otherwise. Further, SOLS change captures changes in the political leader’s supporting societal coalition, coded as 1 if there is at least one SOLS change that lasts longer than 30 days in the year and 0 otherwise (Leeds & Mattes, 2021). Further, a variable Government stability from the PRS dataset is included to account for the possibility that governments may engage in short-term planning if their political survival is uncertain, and hence make decisions without regards for medium and long-term societal consequences.

Governments might also have ideological attitudes towards international regimes which can explain their actions towards BIT commitments, and differ how responsive they are to civil society sentiment as a result (Calvert, 2018a; Montal, 2019). Some states can gain domestic political benefits from taking a strong stand against ISDS, such as in the Ecuador’s leftwing leadership through the two Correa governments (Conaghan, 2008; Becker, 2013). Leftist executive is a binary measure capturing whether or not the executive of the country is labelled as communist, socialist, social democratic or left-wing in the Database of Political Institutions (Cruz et al., 2021), as left-wing movements have been especially proactive in initiating BIT reform.

In addition, the factors driving renegotiation and termination of BITs are likely to differ. As more states have opted to unilaterally terminate their BITs, this might also incentivize other states to follow suit, possibility controlled for by year fixed effects in the employed models.Footnote 19 While the success of renegotiation is likely to depend on various negotiation dynamics, Bureaucratic quality is likely to lower the costs and increase the likelihood of renegotiation success. It is accounted for by the variable from PRS dataset, higher values corresponding to higher strength an expertise to govern without drastic changes in policy.

Finally, whether the bargaining power dynamic also influences the contents of BITs rather than merely the instance of BIT termination and renegotiation is examined. I capture whether there has been a change in the direction of larger state regulatory space (SRS) using data from Thompson et al., (2019). Because desire for greater SRS might motivate many states to seek BIT reform, the impact of shifting bargaining power can also influence the extent to which it is achieved. Delta SRS ISDS captures change in SRS in ISDS provisions, while Delta SRS Subs. measures changes in substantive treaty provisions based on the SRS value of the initial BIT and its replacement. Positive values in these variables indicate an increase in SRS and negative values indicate a decrease. All the variables are summarized in Table A1 in the Appendix.

3.1.1 Method

The main model presented is a linear probability model with fixed effects for each individual BIT and year. Linear probability model is chosen as the main model for the ease of interpretation of the interaction effects of interest.Footnote 20 To ensure that the rarity of events in the data does not influence the results, survival analysis is conducted using a Cox Proportional Hazard model. To acknowledge variation in the different BIT outcomes, I also substitute the outcome variable to assess the effect of hypothesized variables on unilateral terminations and renegotiations separately.

I address further concerns of endogeneity by employing fixed effects and lagging all independent variables by two years, indicated by the t-2 subscript. The treaty-fixed effects αij address the concern that design features in BITs or the relationship between the partner states may be driving the results by controlling for all time-invariant factors that are specific to the treaty or the country dyad.Footnote 21 The year fixed effects δt-2, on the other hand, enable accounting for any year-specific trends that are constant across entities but vary over time, such as general trends in the world economy, overall accumulation of ISDS-disputes or BIT terminations, or any major world events in a specific year. The main model estimated is presented by Eq. 2

where \({Deviation}_{ijt}\) is the dependent variable whether the BIT between states i and j on a year t gets terminated or renegotiated. \({BP}_{ijt-2}\) is the relative economic power change since the initial year of treaty signature. \({X}_{it-2}\) and \({X}_{jt-2}\) are sets of time- and state-varying observable variables, while \({X}_{ijt-2}\) is a set of time- and dyad-varying variables. \({}_{ij}\) is the treaty fixed effect, \({}_{t-2}\) is the year fixed effect, and \({u}_{ijt-2}\) is the idiosyncratic error.

The main goal is therefore to investigate whether there are interaction effects between bargaining power constraints and variables capturing the weaker state’s incentives when estimating the likelihood of BIT deviation. Because different treaties can be nested within the same country dyads, this dependence of treaty-year observations may be a cause of concern for consistency of the standard errors. I account for this by clustering standard errors at the dyad-level. Although there is significant overlap between BIT and dyad fixed effects, I run the models using both as a robustness check.Footnote 22

4 Results

4.1 Interaction effects

The key finding of the analysis is that there are interaction effects with the relative power change variable across different incentives for the weaker state. In all models conducted, decreasing relative economic power gap amplifies the effect of the initially weaker states’ reform incentives – number of ISDS cases as respondent, economic growth, and law and order. In other words, bargaining power change between the treaty partners is found to condition the impact of other developments on investment treaty reform. The results from the main linear probability models are reported in Table 1.

The results contribute to the discussion on the effect of ISDS on the backlash against BITs. Most notably, the impact of ISDS experience depends on bargaining power change. The interaction effect between relative power change and ISDS Respondent for the weaker party is negative and statistically significant, supporting Hypothesis 1. Relative power change between the parties in favor of the weaker state results in a larger effect of an additional investment dispute the weaker party faces on the likelihood of deviating from the BIT.

Figure 3 shows graphically the conditional effects of the three incentive-variables of the weaker party on deviation from the BIT for different levels of the relative power change, as reported in Model 4 in Table 1.Footnote 23 Narrowing of the relative power gap corresponds to greater positive effect of the weaker party’s incentives on BIT deviation.

Conditional effects of initially weaker state’s incentives on BIT Deviation by Relative power change, LMP with year and BIT FEs, SEs clustered by dyad (Model 4. Table 1).

It is remarkable that the broad, structural bargaining power variable has a detectable effect on the specific policy-decisions regarding BITs. Substantively, an economic power change of approximately − 0.144 (1st quartile of the distribution) had taken place when South Africa unilaterally terminated a BIT with Germany in 2014 since signing the treaty in 1995. The linear prediction for the effect of an additional ISDS case against the initially weaker state in such BITs increases the likelihood of its deviation by 0.2%.Footnote 24 On the other hand, economic power change of magnitude of 0.02 (3rd quartile) took place between the signatory states such as South Korea and Bangladesh between their BIT signature in 1986 and 2019. Such widened power gap negates the effect of an additional ISDS case against the weaker state, making no difference to the likelihood of BIT reform (effect size of 0.04%, not statistically significant at 95% confidence level). Changed power dynamics therefore determine whether faced ISDS cases make any difference to whether the BIT stays in place or not.

Results in Fig. 3. suggest a puzzling finding that additional ISDS cases faced by the weaker state make BITs less likely to get renegotiated or terminated at higher levels of relative power change. If the theory is correct and decreasing bargaining power difference enables weaker states to act on their reform incentives, we would not expect any effect when the power asymmetry has worsened. To test this, Model 4 from Table 1 is run separately for two subsets of the data: treaty-years where the weaker party has gotten relatively weaker (12,781 observations) and where the weaker party has caught up (25,883 observations). In the former subset where relative power change is larger than zero, the interaction effect has disappeared, while it remains negative and statistically significant for relative power change values smaller than zero (Fig. 4.) Indeed, it is precisely the closing bargaining power gap that amplifies the effect of ISDS experience on BIT outcomes.

Conditional effects of initially weaker state’s incentives on BIT Deviation by Relative power change in two subsets of the data, where bargaining power gap has closed and where it has increased since BIT signature. Interaction effect is not statistically significant for positive values of relative power change. LMP with year and BIT FEs, SEs clustered by dyad (Table 1. Model 4.)

Negative interaction effects are also detected for measures capturing economic growth and law and order of the initially weaker state, providing support for Hypotheses 2 and 3. Closing the bargaining power gap creates conditions where economic growth as well as improved law and order in the initially weaker state correspond to increased chance of BIT reform.

Because the handful of states who have overtaken their partner in terms of economic power should be expected to be the most empowered to overhaul existing international agreements, the analysis is replicated accounting for such instances, of which there are only a small number of cases (Table A2 in the Appendix). Although no interaction effects are detected in models where the relative power change variable is substituted with the overtook-variable, the independent effect of overtaking is positive and statistically significant, as is the law and order -variable for the initially weaker party, increasing the likelihood of change in BITs.Footnote 25 It is likely that states who alter the bargaining power dynamic the most are also the most likely to also initiate changes in their economic agreements.

A series of robustness checks is conducted to confirm the results of hypothesis testing. The linear probability model with two-way fixed effects may be sensitive to the limited variation in the outcome variable. To ensure that the rarity of instances of termination and renegotiation of BITs in the data is not a concern, survival analysis using a Cox Proportional Hazard model is conducted. In addition, the BIT fixed effects are substituted with dyad fixed effects in one specification, and fixed effect logistic regression is also estimated.Footnote 26 Finally, the theorized dynamic should be expected to manifest best where the asymmetric bargaining power dynamics have been the greatest. I therefore subset the data to include only North-South BITs.Footnote 27 All the estimated models return negative and statistically significant coefficients for the hypothesized interaction effects between relative power change and the weaker party’s incentives.

4.1.1 Independent effects

In addition to the results from hypothesis testing, a set of observations are noted from the independent effects of the main variables. Although one should expect small effect sizes for broad societal and macroeconomic factors on specific policy decisions, the independent effect of facing ISDS cases has a remarkably small effect on the likelihood of BIT termination or renegotiation. Models 3 and 4 reported in Table 1. attribute less than 0.01% increase in the probability of change in the BIT per additional ISDS dispute of the initially weaker state. The equivalent coefficient for the initially stronger state ceases to be statistically significant in the fully restricted model. This is somewhat surprising given the explanatory power attributed to experiencing ISDS in the literature.

Considering the possibility that the cumulative ISDS respondent experience may not be the only determinant of learning, the fully restricted model is replicated with alternative measures for ISDS experience.Footnote 28 The effect of the initially weaker state facing larger numbers of ISDS cases has a larger and statistically significant effect, with some 0.3% increase in the probability of BIT deviation per additional ISDS case. It is possible that larger waves of arbitration faced have a stronger impact on a government than the cumulative ISDS experience.Footnote 29 The other two measures, ISDS respondent any and cumulative ISDS home experience, do not have a statistically significant effect on BIT change for either signatory party. This is likely because states have formed new BITs with different partners even after already experiencing their first ISDS case, and hence it is likely to have little impact on newer agreements. The null effect of ISDS home country experience is also in line with the findings of previous research, suggesting that states only learn and react to the risk of BITs after being in the receiving end of lawsuits.

The effect of law and order in the initially weaker party has a consistently positive and statistically significant effect on BIT deviation in all models conducted. The finding suggests that as the initially weaker party improves the strength and impartiality of its legal system and the popular observance of law (PRS Group, 2020, p. 5), the BIT becomes increasingly likely to get unilaterally terminated or renegotiated. One score increase in the 6-point discrete scale is associated with an increase of between 0.5% and 1.15% in the different linear probability models. While the economic growth of the stronger party is associated with increased probability of BIT deviation, its independent effect is not particularly stable across different models and specifications.

Although relative power changes present an important conditioning factor in the BIT regime, there is only partial evidence for its independent effect on treaty outcomes. The independent effect of the bargaining power change variable is positive and statistically significant in the models reported in Table 1; however, the effect is highly conditional of the ISDS variable employed for the signatory parties (Table A5 in the Appendix). It appears that while rational choice theory would expect states to adjust their international agreements in light of shifting bargaining power, the effect is not consistently detectable. Instead, as the results of interaction effects indicate, relative power change conditions the effects of other factors, especially for those disadvantaged in bargaining.

4.1.2 Termination vs. renegotiation

Because termination and renegotiation are likely to differ in their determinants, additional analysis is conducted with unilateral termination and renegotiation as separate dependent variables. The results reported in Table 2. compare the strictest linear probability model with two-way fixed effects for the different binary outcomes of deviation, unilateral termination, and renegotiation.Footnote 30

The results for the different types of outcomes reveal how different sources of power in the negotiation dynamic shape BITs. Relative power change, ISDS experience, and improved law and order in the initially weaker state make unilateral termination of the BIT more likely. However, it is the initially stronger state’s ISDS experience, economic growth, and bureaucratic quality that are associated with increased likelihood of successful renegotiation. Furthermore, the hypothesized interaction effects are only statistically significant for unilateral terminations.

These findings suggest that the initially stronger states are more effective in pushing through renegotiation of the terms of investment cooperation, powered by their already strong position as well as likely superior negotiation technical skill and resources. On the other hand, the bargaining power dynamic is better at predicting unilateral terminations, because often the only option for the initially weaker states is to take unilateral action to exit the agreement to achieve change in their terms. These findings have implications for the study of other state exits from international agreements and negotiations, as more treaty terminations can be expected in situations with highly asymmetrical negotiation dynamics.

Although relative economic power change does not predict the instance of BIT renegotiation, it shapes the state regulatory space following BIT reform. The interaction effect between relative power change and the initially weaker party’s experience as ISDS respondent has a negative and statistically significant effect on both Delta SRS Substantive as well as Delta SRS ISDS.Footnote 31 Although the increase in state regulatory space is partially a result of the initially weaker states unilaterally terminating BITs, in the aggregate, states establish less restrictive terms for investment regulation following the initially weaker party’s ISDS experience if the economic power gap has narrowed. In addition, bureaucratic quality of both states leads to lager SRS, highlighting its importance as an additional source of power in investment treaty negotiations.

5 Conclusions

ISDS experience has so far dominated the analysis of changes in the BIT regime. The regulation of international investment is, however, not uniquely exempt from the dynamics of international negotiations: bargaining power considerations are inevitably present whenever inter-state agreements are negotiated. The rationalist account relying on changes in the bargaining power dynamic can provide important insight into on-going changes in the BIT regime. Many different factors influence states’ incentives regarding their investment treaty commitments, ranging from experience with ISDS to becoming otherwise attractive for international investors, and to domestic political factors. Yet, it is important that actors’ ability to act upon their incentives will be constrained by power considerations in the international arena – especially with regards to international investment, shaped by asymmetric inter-state relations.

The results from the presented empirical analysis illustrate how the impacts of various factors motivating especially the initially weaker party in the negotiation relationship to reform BITs depend on bargaining power changes. Experience as respondents in ISDS cases are likely to incentivize states to abandon old BITs, as they are likely to learn from the consequences of investment treaties when facing lawsuits from investors. While the ISDS cases faced by the signatory parties have an independent effect on the likelihood of BIT reform, in line with existing research, if the relative power difference between the parties has gotten smaller, additional ISDS cases faced by the initially weaker party increase the likelihood of BIT termination. Furthermore, if there has been no catching up, or the bargaining power asymmetry has worsened, facing additional ISDS cases by the weaker state does not have any impact on the probability of the old BIT to cease to remain in place.

Interaction effects between relative power change on the one hand, and measures capturing economic growth and improved law and order on the other, likewise have a statistically significant effect on terminating or renegotiating BITs. Weaker states who were likely to initially have signed BITs in the hopes of attracting FDI are likely to seek their reform when they become otherwise favorable for foreign investors. Higher economic growth and improved law and order in the weaker state increase the likelihood of termination or renegotiation of the old BIT more the smaller the economic power difference between the states has gotten. Although the effect sizes detected are small, it is remarkable that bargaining power factors create a detectable impact on such specific policy-outcomes as investment treaty negotiations.

Differences are found in the predictors of unilateral termination and renegotiation of BITs. While the ISDS experience, economic growth, and bureaucratic capacity of the initially stronger state increase the likelihood of successful renegotiations, the initially weaker state’s ISDS experience and improved law and order are associated with increased probability of unilateral termination of the BIT. It is likely that the states that continue to be the stronger parties in the bilateral relations are most successful in adjusting the terms of investment treaties when they develop an interest in doing so. This might also explain why the interaction effects between relative power change and weaker states incentive variables do not have a statistically significant effect on BIT renegotiation. However, when a change in BITs does take place, they are more likely to allow for greater state regulatory space following the initially weaker state’s ISDS experience if it also has caught up economically with the partner.

The current academic and policy discussion surrounding the investment regime has been largely focused on the legal aspects of investment treaty arbitration and the implications for states’ regulatory autonomy. Undoubtedly, better understanding of the legal and technical detail on behalf of policymakers as well as researchers about the regime is certainly called for. However, there are plenty of existing tools of studying international economic governance, inter-state bargaining, and treaty-based cooperation that have largely been overlooked in the often legal-dominated space. Decades of international relations theory indicate that structural factors matter for international outcomes, and they can also help in explaining states’ behavior regarding BITs otherwise left unexplained.

The implications of changing bargaining power dynamics are likely to become more important in the future for the BIT regime. With the dispersion of information on the risks of ISDS and inadequacies of the current investment treaty regime underway, improved alternatives for attraction and regulation of FDI, as well as domestic pressures towards reform, more states are likely to become incentivized to move towards a new model of investment governance. On the other hand, the analysis shows that the impact of these developments will depend to some extent on international bargaining power considerations. When relative power changes have been small, the impacts of the motivations for reform on BITs remain modest. However, we are likely to see new actors becoming more active in the arena of international economic agreements if relative economic power differences decrease between traditional investment treaty partners.

Important questions for further inquiry also emerge from the findings, expanding the research agenda on the investment treaty regime. In addition to the employed economic power -based measures, there is a range of other possible factors that constitute bargaining power in the world economy. In addition to access to alternative agreements, partners, and sources of capital, the interplay of such international bargaining power sources with domestic sources of bargaining power can make for different negotiation outcomes altogether. In addition, future research on factors that determine whether either unilateral denunciation or renegotiation can further improve the explanatory power of models of BIT reform, and interrogate the strategic choice faced by states that must decide the best course of action in pursuit of better terms for their economic cooperation.

The findings from the investment treaty regime can also inform scholars and practitioners beyond the specific issue area. Shifting power dynamics in the world economy are also likely to result in changes in other international governance regimes, as some actors can engage in serious negotiations often for the first time. Furthermore, the findings imply that decisions to withdraw from international agreements always involve a strategic element: even when facing strong incentives to exit, such incentives do not always automatically result in political action.

Data Availability

Replication code and dataset for the conducted analysis are available online at the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

Notes

Overall, the association between ISDS cases a state has faced and how many BITs they have resorted to unilaterally terminate or renegotiate is weak, see Figure A1 in Online Appendix, available on the Review of International Organizations webpage.

It has also been found that terminating BITs may exclude states from receiving financing from institutions such as IMF and the World Bank, which implicitly consider BITs a part of providing sufficient legal guarantees for the treatment of investors (Mossallam, 2015).

States can replace old BITs by negotiating a new investment treaty or a more comprehensive economic agreement with investment provisions. After conclusion of a new agreement, the old BIT ceases to be in force (Bernasconi-Osterwalder et al., 2020). Because negotiation processes take time, effort, and diplomatic resources, recent policy discussions have also explored less costly ways for reshaping the investment treaty regime, for example, through issuing joint interpretative statements for arbitration proceedings (Poulsen & Gertz, 2021).

While mutual termination of BITs through an exchange of notes (note verbal) would arguably be the least costly means to adjust terms of investment cooperation, it is empirically a rare instance. Most of the mutually terminated BITs have been intra-EU BITs, following the Achmea ruling by the European Court of Justice that arbitration clauses in BITs are incompatible with EU law (Foucard & Krestin, 2018).

The Council of the European Union gave the EU Commission a mandate to begin to negotiate the creation of a multilateral investment court in 2018, which manifests a European effort to replace the system of ad hoc arbitration tribunals (Bungenberg & Reinisch, 2020).

Because investors form powerful interest groups in most democratic states, their governments are motivated to serve their interests. These states took the lead with their drafted model agreements, and the terms of investment governance were largely dictated by such countries and imposed on their treaty partners in the developing world (Salacuse, 1990: 655–75). On the role of the bureaucrats of European capital exporting countries in shaping the investment regime, see St John (2018).

The newly found activism has also become evident through the increasing popularity of South-South BITs, for example the United Arab Emirates having signed 10 new BITs since 2018 with non-Western partners.

Although governments can also learn about the risks of ISDS by being the home states of disputing investors, governments are usually not involved in such arbitrations. Sometimes companies even treaty-shop and establish “mail box companies” in states with favorable investment agreements (van Os & Knotterus, 2011; Chaisse, 2015; Thrall, 2021), and hence have little connection to their home governments beyond legal affiliation.

Despite many governments’ perceptions, whether or not BITs have been successful in attracting FDI in the first place has been a controversial question both in research and policy. For a summary of the empirical challenges, see Bonnitcha et al., 2017 Ch. 6.

For example, Germany’s efforts to transform towards renewable energy sources by banning nuclear energy initiated ISDS cases with foreign investors in the energy sector (Vattenfall AB and others v. Federal Republic of Germany, 2011). Likewise, Australia found itself in legal problems with Philipp Morris and other tobacco companies following its policy to enhance public health by only allowing plain cigarette packaging (Philip Morris Asia Limited v The Commonwealth of Australia, 2017). Recently, the coal phase-out plan by Netherlands provoked an arbitration case in ICSID by a German energy company RWE (Wehrmann, 2021).

The status information of BITs in the dataset are reported as they stood on the 15 h April 2020, when the data was collected.

On the impact of bargaining power on the ratification of international agreements, see Western 2020.

Larger capital exporters were likely less dependent on any given BIT due to their attractiveness to potential alternative economic partners, and hence stronger according to the bargaining power as outside options -approach.

Substantively, one unit decrease in relative power change is equivalent to Party 1 having had 10 times the GDP of Party 2 on the year of BIT signature and ended up with equal economic power in the year of observation. Although large, there are four country dyads which experienced such dramatic change at least in one observation year in the data.

There are 88 dyads where the initially weaker party has overtaken the initially stronger party in terms of GDP, and 17 dyads where the initially stronger party has overtaken the initially weaker party, at least in one observation year.

The data includes instances of BIT amendments reported as Amendment Protocols by UNCTAD, as well as renegotiations that have not been reported to have taken force. Some BITs have also been replaced by PTAs rather than new BITs, which are also included in the variable. Instances of termination by consent are also included in the main outcome variable, as it signals that an agreement regarding reform has been reached by the parties. Exclusion of mutual terminations does not substantively change the results.

The measure is constructed using the Quality of Government dataset Freedom House/Imputed Polity2 -measure (Theorell et al., 2020).

Government representatives frequently share their experiences in investment treaty reform in policy discussion platforms such as those hosted by the UNCTAD, the South Centre, and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), presenting possibilities for policy-diffusion.

Treaty fixed effects address the problem of large amounts of data that would be otherwise required to control for a multitude of factors, such as unique treaty features (i.e. how strict the dispute settlement provisions are, termination provisions, colonial history between partner states, or diplomatic or cultural factors) that do not vary over the study period in a significant majority of the cases.

Table A3 in the Appendix.

Histogram of the relative power change variable is presented in Figure A2 in the appendix.

The equivalent difference made for the non-cumulative measure of ISDS experience is 0.7%. For cases where the initially weaker party has caught up a lot with their stronger counter parts (relative power change < -1), such as China with European partners Austria, Denmark, and Norway, the effect size of ISDS respondent is 0.6%.

The results are however not robust to clustering standard errors by dyad, as there are only a small number of country-pairs where such a large shift in relative economic power change has taken place.

Table A3 in the Appendix.

North-South BITs are identified as those where the initially stronger party was a member of the OECD while the initially weaker party was not, constituting 32,062 of the BIT years in the dataset. Table A4 in the Appendix.

Table A5 in the Appendix.

While the larger numbers of ISDS cases for the initially stronger state have a negative effect on the likelihood of BIT termination or renegotiation in one specification, the effect is not detected in any of the other models.

Because of the rarity of instances, and the Leftist executive -control variable having a large amount of missing data, it is left out from the specifications presented in Table 2.

Table A6 in the Appendix.

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). ‘Why States Act through Formal International Organizations’. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32

Allee, T., & Elsig, M. (2016). ‘Why do some international institutions contain strong dispute settlement provisions? New evidence from preferential trade agreements’. The Review of International Organizations, 11(1), 89–120

Allee, T., & Elsig, M. (2019). ‘Are the Contents of International Treaties Copied and Pasted? Evidence from Preferential Trade Agreements’. International Studies Quarterly, 63(3), 603–613

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2010). ‘Delegating Differences: Bilateral Investment Treaties and Bargaining Over Dispute Resolution Provisions’. International Studies Quarterly, 54(1), 1–26

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2014). ‘Evaluating Three Explanations for the Design of Bilateral Investment Treaties’. World Politics, 66(1), 47–87

Alschner, W., & Skougarevskiy, D. (2016). ‘Mapping the Universe of International Investment Agreements’. Journal of International Economic Law, 19(3), 561–588

Arias, E., Hollyer, J. R., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2018). ‘Cooperative Autocracies: Leader Survival, Creditworthiness, and Bilateral Investment Treaties*’. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 905–921

Axelrod, R., & Keohane, R. O. (1985). ‘Achieving Cooperation under Anarchy: Strategies and Institutions’. World Politics, 38(1), 226–254

Axelrod, R. M. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books

Baltagi, B. H. (2014). Econometric Analysis of Panel Data. Wiley Global Education

Becker, M. (2013). ‘The Stormy Relations between Rafael Correa and Social Movements in Ecuador’. Latin American Perspectives, 40(3), 43–62

Behn, D., Berge, T. L., & Langford, M. (2017). ‘Poor States or Poor Governance: Explaining Outcomes in Investment Treaty Arbitration’. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 38, 333

Berge, T. L. (2021). State Capacity in the International Investment Treaty Regime. University of Oslo

Berge, T. L., & St John, T. (2021). ‘Asymmetric diffusion: World Bank “best practice” and the spread of arbitration in national investment laws’. Review of International Political Economy, 28(3), 584–610

Berge, T. L., & Stiansen, Ø. (2016). Bureaucratic Capacity and Preference Attainment in International Economic Negotiations. Negotiating BITs with Models. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2851454

Bergès, F., & Chambolle, C. (2009). ‘Threat of Exit as a Source of Bargaining Power’. Recherches Économiques de Louvain/ Louvain Economic Review, 75(3), 353–368

Bernasconi-Osterwalder, N., et al. (2020). Terminating a Bilateral Investment Treaty. International Institute for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/terminating-treaty-best-practices-en.pdf (Accessed 29 July 2021)

Billing, T., & Lugg, A. D. (2019). ‘Conflicted Capital: The Effect of Civil Conflict on Patterns of BIT Signing’. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(2), 373–404

Bonnitcha, J., Poulsen, L. N. S., & Waibel, M. (2017). The Political Economy of the Investment Treaty Regime. Oxford University Press

von Borzyskowski, I., & Vabulas, F. (2019). ‘Hello, goodbye: When do states withdraw from international organizations?’. The Review of International Organizations, 14(2), 335–366

Brooks, S. M., Cunha, R., & Mosley, L. (2015). ‘Categories, Creditworthiness, and Contagion: How Investors’ Shortcuts Affect Sovereign Debt Markets’. International Studies Quarterly, 59(3), 587–601

Broude, T., Haftel, Y. Z., & Thompson, A. (2017). ‘The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Regulatory Space: A Comparison of Treaty Texts’. Journal of International Economic Law, 20(2), 391–417

Bungenberg, M., & Reinisch, A. (2020). From Bilateral Arbitral Tribunals and Investment Courts to a Multilateral Investment Court: Options Regarding the Institutionalization of Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Springer Nature

Calvert, J. (2018a). ‘Civil Society and Investor–state Dispute Settlement: Assessing the Social Dimensions of Investment Disputes in Latin America’. New Political Economy, 23(1), 46–65

Calvert, J. (2018b). ‘Constructing investor rights? Why some states (fail to) terminate bilateral investment treaties’. Review of International Political Economy, 25(1), 75–97

Chaisse, J. (2015). ‘The Treaty Shopping Practice: Corporate Structuring and Restructuring to Gain Access to Investment Treaties and Arbitration’. Hastings Business Law Journal, 11(2), 225–306

Chakrabarti, A. (2001). ‘The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments: Sensitivity Analyses of Cross-Country Regressions’. Kyklos, 54(1), 89–114

Conaghan, C. M. (2008). ‘Ecuador: Correa’s Plebiscitary Presidency’. Journal of Democracy, 19(2), 46–60

Cruz, C., Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2021). The Database of Political Institutions 2020 (DPI2020). Inter-American Development Bank

Debre, M. J. (2021b). ‘The dark side of regionalism: how regional organizations help authoritarian regimes to boost survival’, Democratization, 28(2), pp. 394–413

Debre, M. J. (2022). Clubs of autocrats: Regional organizations and authoritarian survival, The Review of International Organizations, 17, 485–511

Elkins, Z., Guzman, A. T., & Simmons, B. A. (2006). ‘Competing for Capital: The Diffusion of Bilateral Investment Treaties, 1960–2000’. International Organization, 60(4), 811–846

Fisher, R., & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in. Random House

Foucard, C., & Krestin, M. (2018). The Judgment of the CJEU in Slovak Republic v. Achmea – A Loud Clap of Thunder on the Intra-EU BIT Sky!, Kluwer Arbitration Blog. Available at: http://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2018/03/07/the-judgment-of-the-cjeu-in-slovak-republic-v-achmea/ (Accessed: 29 July 2021)

Gray, J. (2013). The Company States Keep: International Economic Organizations and Investor Perceptions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Gray, J. (2018). ‘Life, Death, or Zombie? The Vitality of International Organizations’. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 1–13

Gray, J., & Hicks, R. P. (2014). ‘Reputations, Perceptions, and International Economic Agreements’. International Interactions, 40(3), 325–349

Guzman, A. T. (1998). ‘Why LDCs Sign Treaties that Hurt Them: Explaining the Popularity of Bilateral Investment Treaties’. Virginia Journal of International Law, 38, 639–688