Abstract

Political risk frequently impedes the flow of capital into developing countries. In response, governments often adopt innovative institutions that aim to attract greater flows of international investment and trade by changing the institutional environment and limiting the risk to outside investors. One primary example of this is the Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), aimed specifically at increasing the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) to developing countries. Yet the literature in political science and economics is inconclusive about whether or not BITs do indeed stimulate FDI, and it provides conflicting theoretical reasoning for the claimed connection. This article argues that BITs do attract FDI to developing countries, but the story is a complicated one. Two important factors must be taken into account. First, BITs cannot entirely substitute for an otherwise weak investment environment. Countries must have the necessary domestic institutions in place that interact with BITs to make these international commitments credible and valuable to investors. Second, as the coverage of BITs increases, overall FDI flows to developing countries increase. However, although remaining positive, the marginal effect of a country’s BITs on its own FDI may fall because of heightened competition for FDI from other BIT countries. Using data from 97 countries for 1984–2007, we provide empirical evidence consistent with both of these theoretical claims.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is important to distinguish our claim from the claim that the effort to attract FDI to developing countries is a zero-sum gain. That is not our claim. We expect the pie to expand as the number of BITs increases, but as the number of treaties increases, individual countries cannot differentiate themselves from others on the basis of their commitment to the BITs’ regime.

For example, Kerner (2009), Büthe and Milner (2008, 2009), Salacuse and Sullivan (2004) and Neumayer and Spess (2005) find strong correlations between BITs and FDI flows. At the same time, using a different set of models and assumptions, Hallward-Driemeier (2003) and Tobin and Rose-Ackerman (2005) find little evidence of this connection.

An exception is NAFTA that includes an investment chapter covering the United States, Canada and Mexico.

Montt (2009: 65–66) and Peinhardt and Allee (2010) document the rise of investor-state arbitration clauses in BITs. Investor-state arbitration made BITs more useful to investors who no longer needed to obtain the support of their home governments when a dispute arose. BITs generally provide for resolution of investor-host country disputes by the World Bank Group’s International Center for the Settlement of International Disputes (ICSID), which was created especially to handle such disputes www.worldbank.org/icsid. The ICSID Convention was formulated by the Executive Directors of the World Bank in 1965 and went into force in 1966 after it was ratified by twenty countries. The ICSID website reports that 144 countries had ratified the Convention by April 2010 (http://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=CasesRH&actionVal=ShowHome&pageName=MemberStates_Home).

The BITs regime is not an “international organization” in the sense used by Mansfield and Pevehouse (2008). They define an international organization as one that has an institutionalized international presence that has a staff, a headquarters, and holds regular meetings. Nevertheless, the growing collection of BITs serves many of the same functions in the global economy as more institutionalized organizations that impose constraints on state behavior.

For the contrasting view see Ginsburg (2005).

Of course, in the coming decades, as MNCs from some emerging economies such as China, India and Brazil, begin to invest in other countries, our focus on FDI that originates in developed countries will need to be modified.

Here and in our empirical tests, we simplify the signaling function of BITs by assuming that all BITs with developed countries are of equal weight. A more complex model might take account of the identity of treaty partners beyond a division between developed countries and those classified as developing or emerging economies. One might posit that BITs with large economies or those that invest heavily abroad would send a stronger signal. This is a plausible supposition, and we have experimented with alternative weighting systems to take this possibility into account. Specifically, we weighted BITs by two different factors: the home country’s significance in FDI flows to developing countries and the home country’s significance as an economic power (its overall GDP). However, because the results differed little from those reported in the text, we have retained the original, simpler formulation. Although, in principle, the identity of the signatories might matter, in practice, this appears not to be an important factor in understanding the impact of BITs in the late twentieth century.

Note that these scores conflate the expected value of investments and their riskiness into a single index number that represents the certainty equivalent of investment. One can think of BITs as improving both mean and variance so that the certainty equivalent of investment projects increases for the country in question.

In the most comprehensive study looking at why countries sign BITs, Elkins et al. (2006) find that the proliferation of BITs is a result of competitive economic pressures among developing countries to capture greater shares of foreign investment.

Of course, different firms face different options. According to one effort at synthesis, foreign investment decisions are a function of ownership, internalization, and locational advantages (Rugman 1980; Dunning 2001). Ownership advantages are the advantages that particular firms hold over their rivals. They imply some form of imperfect competition that benefits some foreign firms over others and over domestic firms. Internalization advantages focus on the efficiency of direct investment over the sale of goods and services to foreign firms in host countries through contractual agreements. They stem from the high costs of contracting and the desire not to reveal insider knowledge. These two factors are tied to the characteristics of particular MNCs. We do not study these aspects of investment choice.

Looking at total FDI from a variety of firms, Chakrabarti (2001) found that market size was positively correlated with FDI flows in all the articles that he reviewed.

The merits of democracy in attracting FDI are contested. Several scholars argue that democratic institutions provide better property rights protection, policy stability, and lower political risks and, are therefore, more attractive environments to foreign investors (World Bank 2005; Jensen 2006). However, the empirical evidence linking FDI flows to democratic governments is weak. Li and Resnick (2003) argue that the greater political participation and representation inherent in democracies may constrain their ability to attract FDI because of less favorable conditions for foreign investors, such as higher taxes and labor-friendly policies (Henisz 2000). Although most wealthy democracies also have strong property rights regimes, the link is less tight in the poorer parts of the world (Jakobsen and de Soysa 2006). If democracy plays a role in determining FDI, it appears to do so mainly through its ability to create stable institutions and strong property rights, which, in turn, contribute to profitability. See also Goldsmith (1995), LeBlang (1996) and Grabowski and Shields (1989).

All of the interactive specifications naturally include a high degree of collinearity between the variables. Following Franzese and Kam (2007), we believe that in spite of the high standard errors inherent in this approach, we are warranted in using it to ensure that our model matches our theory.

Summary statistics are available in Appendix A.

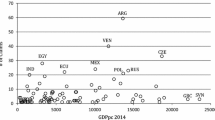

Choi and Samy (2006) compare two papers with divergent findings on the relationship between democracy and FDI and find the difference to be a result of the form of the dependent variable—that is the decision to employ net FDI inflows (Li and Resnick 2003) versus using a ratio of FDI to GDP (Jensen 2003). Choi and Samy (2006) show that empirically the difference results from outliers clearly apparent in the FDI/GDP study that were not removed in the net inflows study. Our dataset, which comes from the same source as both of the earlier studies, clearly indicates the presence of similar outliers. In our robustness checks we show that neither removal of the outliers nor measuring FDI as a percentage of GDP has an undue impact on our results.

It has become standard practice in the literature on FDI to use the log, rather than the level of FDI as the dependent variable. The log specification reduces the weight of observations with very high FDI flows and ensures homoskedasticity in the error term.

There are three components of FDI: equity capital, reinvested earnings, and intra-company loans. If one of these three components is negative and is not offset by positive amounts in the remaining components, the resulting measure of FDI inflows can be negative, indicating disinvestment.

The results from using a count of BITs signed rather than just those in force did not significantly change the results of the analysis.

Many PTAs currently include an investment chapter that is equivalent to a BIT. Although these investment chapters are not included in most available lists or counts of BITs, we code them as BITs and include them in our count of BITs because they are for all intents and purposes indistinguishable from a BIT.

We only consider BITs with high income (OECD) countries on the ground that they are the ones with the potential to have an impact on FDI flows during the time period of our study.

Including the ICRG variable limits the number of countries included in the analysis. If we exclude the ICRG index, 21 additional countries are added. However, its exclusion does not change our results significantly, and as no other widely available measure takes account of our theoretical construct of political risk, we include it in the final analysis. Results with its exclusion are available from the authors.

Our time period is constrained by the availability of political risk data. In our robustness checks we substitute for a measure of democracy that allows a longer time frame, but the results are not unduly affected.

We are not concerned with FDI between wealthy countries most of which have strong domestic legal environments and do not sign BITs with each other.

Because of the possibility of different structural relationships for very small countries, as is the custom in the broader literature on economic growth and foreign investment, we eliminate countries with a population below one million from our sample (Büthe and Milner 2008).

We include results using yearly data in the table on robustness checks.

We do include the best instrument available for BITs, detailed below.

We use the Sargan test to assess the validity of our instruments. The null hypothesis is that the instruments are uncorrelated with the error term (i.e., are valid instruments), and a rejection of the null hypothesis at conventional levels of statistical significance means that instruments are not valid. We report the p-value of the Sargan test, where anything greater than 0.10 indicates that the instruments are valid.

Neighbor is defined as all contiguous countries with either a common border or less than 150 nautical miles between the countries.

Arellano-Bond deals with time-specific factors identically to 2SLS-IV, with the addition of time dummies. Additionally, it accounts for country-specific factors through first-differencing.

We chose 250 BITs, the number of treaties in place in 1990 when BIT signing increased from an average of 10–20 per year to an average of 50 per year.

The correlation between the two dependent variables for the data points that they have in common is 0.76.

Results available from authors.

References

Abbott, F. M. (2000). NAFTA and the legalization of world politics: a case study. International Organization, 54, 519–547.

Abbott, K., & Snidal, D. (2000). Hard and soft law in international governance. International Organization, 54(3), 421–456.

Alfaro, L., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Volosovych, V. (2007). Capital flows in a globalized world: The role of policies and institutions. In E. Sebastian (Ed.), Capital controls and capital flows in emerging economies: Policies, practices, and consequences (pp. 19–71). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Alfaro, L., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Volosovych, V. (2008). Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries? An empirical investigation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(2), 347–368.

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2008). Not the least BIT rational: An empirical test of the ‘rational design’ of investment treaties. In Conference on the political economy of international organizations. Monte Verità, Switzerland.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equation. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at instrumental variable estimation of error-component models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51.

Barro, R., & Lee, J.-W. (2000). International data on educational attainment: Updates and implications. CID Working Paper No. 42.

Blonigen, B. (2005). A review of the empirical literature on FDI determinants. Atlantic Economic Journal, 33(4), 383–403.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bubb, R., & Rose-Ackerman, S. (2007). BITs and bargains: strategic aspects of bilateral and multilateral regulation of foreign investment. International Review of Law and Economics, 27(3), 291–311.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. (2008). The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: increasing FDI through trade agreements? American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 741–762.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2009). Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: A political analysis. In K. P. Sauvant & L. E. Sachs (Eds.), The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows (pp. 171–224). New York: Oxford University Press.

Chakrabarti, A. (2001). The determinants of foreign direct investments: sensitivity analyses of cross-country regressions. Kyklos, 54(1), 89–114.

Choi, S.-W., & Samy, Y. (2006). Puzzling through: The impact of regime type on inflows of foreign direct investment. In Unpublished Manuscript.

Dolzer, R., & Stevens, M. (1995). Bilateral investment treaties. The International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Dunning, J. H. (2001). The Eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: past, present and future. International Journal of Economics and Business, 8(2), 173–190.

Eichengreen, B., & Irwin, D. (1995). Trade blocs, currency blocs, and the reorientation of trade in the 1930s. Journal of International Economics, 38, 1–24.

Eichengreen, B., & Irwin, D. (1997). The role of history in bilateral trade flows. In J. Frankel (Ed.), The regionalization of the world economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Elkins, Z., Guzman, A., & Simmons, B. (2006). Competing for capital: the diffusion of bilateral investment treaties, 1960–2000. International Organization, 60, 811–846.

Franzese, R., & Kam, C. (2007). Modeling and interpreting interactive hypotheses in regression analysis: A brief refresher and some practical advice. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ginsburg, T. (2005). International substitutes for domestic institutions: bilateral investment treaties and governance. International Review of Law and Economics, 25, 107–123.

Goldsmith, A. (1995). Democracy, property rights and economic growth. Journal of Development Studies, 32(2), 157–175.

Grabowski, R., & Shields, M. (1989). Lewis and Ricardo: a reinterpretation. World Development, 17(2), 193–198.

Granger, C., & Newbold, P. (1974). Spurious regressions in econometrics. Journal of Econometrics, 2, 111–120.

Guzmán, A. (1998). Why LDCs sign treaties that hurt them: explaining the popularity of bilateral investment treaties. Virginia Journal of International Law, 38, 639–688.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Montgomery, A. H. (2008). Power or plenty: how do international trade institutions affect economic sanctions? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(2), 213–242.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., von Stein, J., & Gartzke, E. (2008). International organizations count. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(2), 175–188.

Hallward-Driemeier, M. (2003). Do bilateral investment treaties attract FDI? Only a bit...and they could bite. In World bank policy research working paper. Washington: World Bank.

Hansen, L. (1982). Large sample properties of generalised method of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50, 1029–1054.

Henisz, W. (2000). The institutional environment for multinational investment. Journal Of Law Economics & Organization, 16(2), 334–364.

Jakobsen, J., & de Soysa, I. (2006). Do foreign investors punish democracy? Theory and empirics, 1984–2001. Kyklos, 59(3), 383–410.

Jensen, N. (2003). Democratic governance and multinational corporations: political regimes and inflows of foreign direct investment. International Organization, 57(3), 587–616.

Jensen, N. (2006). Nation-states and the multinational corporation: Political economy of foreign direct investment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jun, K., & Singh, H. (1996). The determinants of foreign direct investment in developing countries. Transnational Corporations, 5(2), 67–105.

Keefer, P. (1999). When do special interests run rampant? Disentangling the role in banking crises of elections, incomplete information, and, checks and balances in banking crises. In The world bank, policy research working paper series. Washington: World Bank.

Kerner, A. (2009). Why should i believe you? The costs and consequences of bilateral investment treaties. International Studies Quarterly, 53(1), 73–102.

Kosack, S., & Tobin, J. (2006). Funding self-sustaining development: the role of aid, FDI and government in economic success. International Organization, 60(1), 205–243.

Leblang, D. (1996). Property rights, democracy and economic growth. Political Research Quarterly, 49(1), 5–27.

Levy Yeyati, E., Panizza, U., & Stein, E. (2007). The cyclical nature of north-south FDI flows. Journal of International Money and Finance, 26(1), 104–130.

Li, Q., & Resnick, A. (2003). Reversal of fortunes: democratic institutions and foreign direct investment inflows to developing countries. International Organization, 57(1), 175–211.

Manger, M. S. (2009). Investing in protection: The politics of preferential trade agreements between North and South. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2008). Democratization and the varieties of international organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(2), 269–294.

Marshall, M., & Jaggers, K. (2008). Polity IV project. University of Maryland. Available from http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/polity/.

Martin, L. L. (2000). Democratic commitments: Legislatures and international cooperation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Montt, S. (2009). State liability in investment treaty arbitration: Global constitutionalism and administrative law in the BIT generation. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Neumayer, E., & Spess, L. (2005). Do bilateral investment treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries? World Development, 33(10), 1567–1585.

Noorbakhsh, F., Paloni, A., & Youssef, A. (2001). Human capital and FDI inflows to developing countries: new empirical evidence. World Development, 29(9), 1593–1610.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peinhardt, C., & Allee, T. (2010). Devil in the details: The investment effects of dispute settlement variation in BITs. Paper presented at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the International Political Economy Society. Palo Alto, CA.

Phillips, P. (1987). Time series regression with a unit root. Econometrica, 55(2), 277–301.

Roodman, D. (2009). How to xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136.

Root, F., & Ahmed, A. (1979). Empirical determinants of manufacturing direct foreign investment in developing countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 27, 751–767.

Rugman, A. (1980). Internalization as a general theory of foreign direct investment: a re-appraisal of the literature. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 116(2), 365–379.

Salacuse, J., & Sullivan, N. (2004). Do BITs really work? An evaluation of bilateral investment treaties and their grand bargain. Harvard International Law Journal, 46(1), 67–130.

Sargan, J. D. (1958). The estimation of economic relationships using instrumental variables. Econometrica, 26, 393–415.

Schneider, F., & Frey, B. (1985). Economic and political determinants of foreign direct investment. World Development, 13, 161–175.

Simmons, B. (2000). International law and state behavior: commitment and compliance in international monetary affairs. American Political Science Review, 94(4), 819–835.

Stock, J., & Watson, M. (1988). Variable trends in economic time series. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(3), 147–174.

Tobin, J. (2008). Interest groups, political investments and property rights enforcement in developing countries. Ph.D. dissertation. Yale University.

Tobin, J., & Rose-Ackerman, S. (2005). Foreign direct investment and the business environment in developing countries: The impact of bilateral investment treaties. In Yale law & economics research papers. New Haven.

UNCTAD. (1999). UNCTAD hosts bilateral investment treaty negotiations by group of fifteen countries. Geneva.

UNCTAD. (2001). Bilateral investment treaties 1959–1999. Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD. (2003). World investment report 2003. New York: United Nations.

UNCTAD. (2006). Developments in international investment agreements in 2005. In IIA monitor. Geneva.

UNCTAD. (2007). Investment instruments online. UNCTAD.

Wawro, G. (2002). Estimating dynamic panel models in political science. Political Analysis, 10, 25–48.

Wei, S.-J. (2000). How taxing is corruption on international investors? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 1–11.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48(4), 817–838.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

World Bank. (2005). World development report 2005: A better investment climate for everyone. Washington: The World Bank.

Yackee, J. (2008). Conceptual difficulties in the empirical study of bilateral investment treaties. Brooklyn Journal of International Law, 33(2), 405–462.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Summary Statistics

Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

FDI | 751.13 | 3931.28 | −513.76 | 76,214 |

Log of FDI | 3.61 | 2.68 | −6.24 | 11.24 |

BITs | 2.22 | 4.14 | 0 | 27 |

World BITs | 339.27 | 350.50 | 5 | 993 |

Political risk (high numbers indicate low risk) | 57.30 | 12.62 | 15.17 | 82.57 |

Log GDP per capita | 6.84 | 1.12 | 4.23 | 9.24 |

GDP growth | 3.94 | 4.87 | −42.45 | 35.89 |

Trade openness | 73.27 | 40.06 | 2.35 | 310.58 |

Natural resources | 27.54 | 38.64 | 0.04 | 602.23 |

Log of population | 15.19 | 2.03 | 9.68 | 20.99 |

Average neighbor BITs | 1.44 | 2.50 | 0 | 14.2 |

Appendix B

Countries Included in Analyses

Albania | Guinea | Panama |

Algeria | Guinea-Bissau | Papua New Guinea |

Angola | Guyana | Paraguay |

Argentina | Haiti | Peru |

Armenia | Honduras | Philippines |

Azerbaijan | Hungary | Poland |

Bangladesh | India | Romania |

Belarus | Indonesia | Russian Federation |

Bolivia | Iran | Senegal |

Botswana | Jamaica | Serbia |

Brazil | Jordan | Sierra Leone |

Bulgaria | Kazakhstan | Slovak Republic |

Burkina Faso | Kenya | South Africa |

Cameroon | Latvia | Sri Lanka |

Chile | Lebanon | Sudan |

China | Liberia | Suriname |

Colombia | Libya | Syrian Arab Republic |

Congo, Dem. Rep. | Lithuania | Tanzania |

Congo, Rep. | Madagascar | Thailand |

Costa Rica | Malawi | Togo |

Cote d’Ivoire | Malaysia | Trinidad and Tobago |

Croatia | Mali | Tunisia |

Czech Republic | Mexico | Turkey |

Dominican Republic | Moldova | Uganda |

Ecuador | Mongolia | Ukraine |

Egypt | Morocco | Uruguay |

El Salvador | Mozambique | Venezuela |

Estonia | Namibia | Vietnam |

Ethiopia | Nicaragua | Yemen, Rep. |

Gabon | Niger | Zambia |

Gambia, The | Nigeria | Zimbabwe |

Ghana | Oman | |

Guatemala | Pakistan | |

N = 97 | ||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tobin, J.L., Rose-Ackerman, S. When BITs have some bite: The political-economic environment for bilateral investment treaties. Rev Int Organ 6, 1–32 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9089-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9089-y