Abstract

International norms and rules are created in international negotiations. A comprehensive survey shows that the satisfaction with negotiation outcomes varies between delegates, states and International Organizations (IOs), which is important as it has potential ramifications for state compliance and the effectiveness of the international rules and norms. This paper investigates which role individual, country and IO features and their interactions play for satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes. Drawing on approaches of international negotiation and cooperation, hypotheses on individual, country and IO features are specified and examined empirically with a multilevel analysis. This reveals that especially individual and IO level features impact outcome satisfaction. Outcome satisfaction increases if delegates put in much work in negotiations and can conduct them flexibly and if IOs are small in size, and have institutional designs that seek to foster debates. The paper also shows that there are cross-level interaction effects. Most notably, the positive effect of flexibility on high outcome satisfaction is less pronounced when negotiations are more strongly characterized by bargaining dynamics. Vice-versa, when IOs are prone to arguing dynamics all actors become more satisfied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The current international system is characterized by a multitude of international rules and norms which are often the result of international negotiations taking place in or being brought about by International Organizations (IOs). This encompasses a broad array of different policy fields and includes hard as well as soft law, thus having substantive effects on state conduct (e.g. Risse, et al. 1999; Cortell and Davis 2000; Shelton 2000). As the current international order is by large a negotiated one, international negotiations are often in the limelight of research (e.g. Kremenyuk 1991; Plantey 2007; Odell 2010; Coleman 2013; Albin and Druckman 2014).

This paper adds to this often qualitative literature that provides in-depth case studies of individual negotiations, as it examines satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes of more than 900 delegates in 173 different countries across 49 IOs selected to vary the policy fields they cover, task-specific and general purpose modes of IO operation as well as their global and regional reach. Thus, this paper provides comprehensive comparative insights into similarities and differences with respect to negotiation success across individuals, states, and IOs. Most strikingly, outcome satisfaction varies not only between individual delegates but also considerably across IOs as negotiation arenas. On the one end of the spectrum there is the International Maritime Organization (IMO) or the Conference on Disarmament (CD) with a rather low outcome satisfaction while actors in IOs such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) are much more satisfied with negotiation outcomes on average. What factors might account for this variation?

While social psychology and business studies provide insights into individual level factors such as flexibility or workload (e.g. Druckman 1983; Bazerman et al. 2001; Rubin and Brown 2013), political science often focuses on country characteristics such as bargaining power or capacities as well as IO features such as membership composition or voting rules when studying dynamics and outcomes of negotiations (e.g. Habeeb 1988; Fearon 1998; Plantey 2007; Panke 2017). Yet, there are no studies that systematically include and vary factors on the individual, country as well as the IO level and also examine how these variables interact across levels.

Thus, the paper sheds light on the following research question by investigating a large number of IOs and actors: Which role do individual, country and IO features and their interactions play for outcome satisfaction in IOs?

The paper is organized into five sections. Section 2 introduces the dependent variable and illustrates how satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes varies between individuals as well as across countries and IOs. In order to account for the observed variation, section 3 uses general negotiation approaches and international cooperation theories to specify hypotheses on individual characteristics, country features, and IO level variables on outcome satisfaction. In addition, section 3 theorizes cross-level interaction effects. To shed light on the empirical plausibility of the hypotheses, section 4 provides a multilevel analysis. This reveals that especially individual and IO characteristics are of importance, while not all country factors play out as expected once we control for the other two levels. Outcome satisfaction is the most pronounced if delegates put in a lot of work into negotiations and have a high level of flexibility to conduct negotiations and when IOs are smaller in size, and allow for dynamic debates between delegates, whilst the IO has institutional rules in place that seek to prevent interruptions of debates.

In general delegates with much room of maneuver in how to conduct negotiations are more satisfied with outcomes than delegates that operate with strings attached. This effect is further enhanced by some IO features. For instance, as negotiations are more strongly characterized by bargaining dynamics, the satisfaction with negotiation outcomes of delegates with high flexibility decreases. Unlike their colleagues, highly flexible delegates cannot effectively use tied-hands strategies and are therefore less successful when bargaining takes place. The concluding part summarizes the major findings and discusses their implications (section 5).

2 Dependent variable and puzzle

This paper examines whether actors regard their own positions reflected in final negotiation outcomes and does so for a large number of different IOs. Outcome satisfaction has been researched in a number of different fields, such as business, organizational and behavioral studies as well as in conflict management (e.g. Bercovitch 1992; Oliver et al. 1994; Purdy et al. 2000; Naquin 2003; Novemsky and Schweitzer 2004; Curhan, et al. 2010; Patton and Balakrishnan 2010). In the field of International Relations, most qualitative studies on negotiation success capture either the question whether the negotiation strategies of actors were effective and enabled an actor to change the negotiation outcome accordingly or capture the overlap between initial positions and the final outcome document. Quantitative negotiation studies often use voting for the final outcome document (rather than rejecting it or strategically abstaining) as a proxy for negotiation success. The former type of studies is based on indicators that require detailed case studies and interviews as well as access to primary sources in order to assess the extent to which an individual actor was successful and therefore focuses on a small number of cases. By contrast, the latter type of negotiation research adopts a large N perspective. Yet, inferring negotiation success from voting can only be done in IOs in which voting takes place and in which roll-call data is publicly accessible, but not the ones in which outcomes are passed by consensus or in which voting records are confidential. This paper, by contrast, uses a survey in order to capture outcome satisfaction across a broad array of different IOs that vary in size and institutional design features such as rules of debates, or voting procedures. A survey as an instrument of data collection has the advantage to gather comparable information across a large number of actors and countries in a large number of IOs, irrespective of whether IOs pass decisions with or without voting and irrespective of how transparent the IO decision-making process is with respect to this process (Panke 2018; Fowler 2013).

The survey was executed among current and former national delegates, aiming to capture their perceptions on numerous issues amongst them the satisfaction with the negotiation outcome, which forms the dependent variable of this paper (see below). The sampling of IOs for the survey took place in several steps. The following six points of criteria establish the basis of the initial selection of the IOs from the IO yearbook and Correlates of War (COW) database: (1) an IO must be still in operation in 2016, (2) must be composed of states rather than, for example, companies, private individuals, or other organizations, (3) have the purpose of creating and reinforcing international norms and rules, (4) allow public access to its institutional rules (e.g. founding treaties and rules of procedures), (5) vary with respect to size, age, policy field, general-purpose and task-specific, and regional vs. global reach, and (6) allow access to information on who participated in IO negotiations in order to be contacted for the survey. Application of the first four criteria to the IO yearbook and Correlates of War (COW) database yields 114 IOs remaining, applying the last two criteria leads to a representative sample of 49 IOs (for a list of IOs included see Table A1 in Appendix). Similar to other research comparing IOs (Tallberg et al. 2013; Hooghe and Marks 2015), our sample of IOs entails well-known organizations and less well-known ones, as well as organizations that are often regarded as highly consequential (e.g. IMF, ILO, IAEA) or playing a lesser role in global governance (e.g. IWC, ITTO, WMO).

After the selection of IOs, we identified our target group in several stages. First, the list of participants, which contains information on country delegates who attended the meetings of the main legislative bodies of the respective IOs in 2016 and 2017, was obtained from IO homepages and, if not available online, was requested from IO secretariats.Footnote 1 In the next step, the contact information (e.g. personalized e-mail addresses, personal office telephone numbers) required for the circulation of the online survey was gathered from a variety of sources, including the homepages of state ministries, national missions abroad, consulates, and other official state agencies with which the delegates were affiliated. Depending on the reporting system of IOs and the transparency of their negotiations and governance structure as well as the transparency of states and the size of their diplomatic missions at IO headquarters, the number of national delegates that could be identified as participating in negotiations varies between IOs and member states.

For IOs in which the participating actors could be identified only for some negotiations, we did not sample the participants, but invited all to the survey. For IOs in which all actors participating in the negotiations in 2016 and 2017 could be identified, we invited all of them if their numbers were limited in total, which was usually the case if their delegations were not too big on average (exceeding an average of 5, e.g. the OIE), and only contacted a maximum of up to 8 participants per member state for IOs in which the list of potential survey participants was very high (e.g. the UNGA, c.f. Table A1). Table A2 provides a summary of survey respondents per country. Due to several factors, there are more responses from some countries than others: First, states that hold more IO memberships receive overall more invitations to the survey. Second, states that have larger ministries back home and larger delegations at the IO negotiation table (e.g. richer states) have more participants to be included in the survey. Third, the more democratic countries are, the more transparent they tend to be with respect to personalized contact information of attendees of international negotiations. Fourth, in some countries the fluctuation of national delegates posted to IOs and located in ministries back home is very high. This reduces the chances to obtain current personalized official e-mail addresses that are still in operation of those delegates that participated in the IO negotiations in 2016 and 2017.

Before running the survey, the questionnaire was translated from English into French, Spanish, and Arabic by native speakers and pre-tested by former diplomats in order to check the quality and intelligibility of the questionnaire. Following this, customized invitation e-mails were sent out to individual participants with a link to the online survey page, explaining the purpose of the research as gathering information on IO institutional design and deliberation and the survey, and providing instructions on how to complete it. Each actor was assigned a unique code to track responses and prevent multiple completion from the same expert, nonetheless, all delegates were assured complete anonymity and their personal data was removed prior to compiling the survey data. After the initial invitation, a second and a third invitation were sent to all who had not responded to the survey and followed up by phone interviews in order to maximize the response rate.

The survey was conducted between May 2018 and July 2019 and included 1079 responses, 997 of which provided an answer for the dependent variable of this paper, outcome satisfaction, from 49 different IOs. The number of surveyed participants for each IO varies depending on several factors such as their size, policy area, and accessibility of participant lists (needed to identify member state delegates and invite them to participate in the survey). In general, the number of evaluations ranges from three (Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America or OPANAL, in short) to as high as 87 (International Office of Epizootics or OIE), nonetheless, the average participation with 38.94 respondents is relatively high, and this number is not skewed by a few IOs with a relatively higher number of respondents. In fact, 38 IOs out of 49 have ten or more respondents. Response rate ranges between 3.05% lowest and 57.69%, with an average value of 22.11% (see Table 1A in Appendix).

2.1 Descriptive analysis

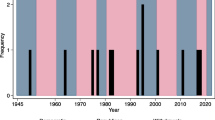

What type of patterns do we observe with respect to outcome satisfaction? To shed light on this question, we used an item in our survey in which participants reported to what extent they usually see their national position reflected in the final outcome. The respondents reported on a five-point Likert scale whether they strongly agree or strongly disagree with the following question: “In the [name of the respective IO], I usually see my national position reflected in the final outcome.”Footnote 2 Accordingly, our dependent variable focuses on the extent of outcome satisfaction and can range from one (least satisfaction) to five (most satisfaction). The dependent variable has a mean value of 3.58, indicating that respondents tend to report at least a moderate level of satisfaction with the outcome. As Graph 1 shows, we observe quite a variation in outcome satisfaction between individual delegates. Despite the clustering of responses around the moderate (three) and high level (four) of outcome satisfaction, some respondents still report relatively lower (one or two) or higher (five) levels of satisfaction. The bulk of the participants reported having a moderate (31.59%) or higher level of outcome satisfaction (45.84%). The highest (five) and the lowest levels of satisfaction (one and two), on the other hand, appear to have much fewer observations. While about 13% of respondents reported having the highest level of satisfaction, only about 3 % of them confined their responses in the least satisfaction whereas somewhat low level outcome satisfaction (two) receives about 7 % of all responses. The former suggests that there is no systematic self-reporting bias at stake when diplomats report their perceptions on how strongly their respective national positions are reflected in the final outcomes, otherwise Graph 1 would portray a strong left-skewed distribution especially with respect to the highest level of outcome satisfaction. This interpretation is supported by Table 1 which shows that outcome satisfaction varies considerably between IOs (from 2.7 to 4.33), with some IO not featuring the highest extent of outcome satisfaction at all (Graph 2).

Countries display quite a variation with respect to the average extent their positions are reflected in IO negotiation outcomes. Overall, 85 out of 173 countries score above the grand mean level of outcome satisfaction (3.58) while 92 countries score below it. Empirically it ranges from one (e.g. Eritrea, Seychelles, St Lucia, and Swaziland) to as high as five (e.g. South Sudan, Senegal, Oman, and Niger) and it is not regionally clustered. For instance, some African countries such as Eritrea and Swaziland have a low level of outcome satisfaction (1.0, each), other African countries such as South Sudan and Senegal exhibit a high level of average outcome satisfaction (5.0, each). In Asia, delegates from India report generally a relatively lower level of outcome satisfaction (2.67) while those from Malaysia (5.0) and Singapore (4.33) are happy with the outcome. The average level of outcome satisfaction in Americas ranges from 1.0 (e.g. St Lucia) to 3.22 (Chile) with the prominent countries in the region such as Brazil and the United States displaying somewhat moderate levels of satisfaction with the outcome (3.47 and 3.76 respectively). Among the European countries, Greece has the lowest score (2.86) and Bulgaria has the highest (4.20) while countries like France (3.61) and Germany (3.74) score only slightly above the general mean level of outcome satisfaction.

In addition to individual-level patterns of outcome satisfaction, Graph 2 maps the relative percentages of each category of outcome satisfaction across 49 IOs in the sample. Compared to Graph 1, the second graph shows a more detailed mapping of our dependent variable. While the general pattern of satisfaction in Graph 1 holds, disaggregated plotting shows that its extent varies across different IOs. Empirically, the average level of outcome satisfaction across IOs ranges between 2.7 (International Maritime Organization or IMO) and 4.33 (ARIPO and OPANAL; see Table 1). This indicates that outcome satisfaction is not realized in relative terms (e.g. is not a zero-sum game, by which the high satisfaction of one actor automatically translates into a low satisfaction of the other actor).

Zooming in on individual IOs and relative percentages of the extent of outcome satisfaction, in turn, provides a more interesting picture. For instance, delegates opted only for the highest level options with respect to their perception of outcome satisfaction in some IOs such as Latin American Energy Organization (OLADE) and Latin American Commission for Civil Aviation (CLAC), while in others (e.g. IMO) the lower category of satisfaction constitutes as high as 40% of all responses. At first glance, this pattern might suggest an IO-level effect which is uniform for its actors, especially on their inclination in reporting similar levels of outcome satisfaction. However, a further look at the graph opposes such an intuition. Since, for example, participants that reported having the lowest and those having the highest level of satisfaction constitute almost the same share in some IOs such as International Labor Organization (6.25% and 8.33%, respectively) and Organization of American States (15.38%, each). Thus, relaxing the presumption that the delegates operate in a uniform manner within the same institutional context could better reveal the driving forces behind outcome satisfaction. For instance, some IO features such as its size and institutional rules might have different effects on outcome satisfaction depending on particular actor characteristics (e.g. their level of flexibility). Nevertheless, the question of whether indeed such an interaction effect exists between the individual characteristics of delegates and the nature of the institutional context in which they operate is a subject of empirical analysis.

3 Theory

With the proliferation of IOs after the end of the Second World War and again after the end of the Cold War the number of international norms and rules has increased considerably. Today there are hardly any policy areas in which no IO is active and for which there are no formal or informal rules and norms in place (Beck et al. 1998; Martin and Simmons 2001; Carlsnaes et al. 2002; Barnett and Finnemore 2004; Alvarez 2005; Armstrong et al. 2010; Archer 2014; Diehl and Frederking 2015). In other words, the anarchical system described by international relations scholars of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g. Morgenthau 1948; Waltz 1959) has been replaced by regulated anarchy that has been created and expanded through multilateral negotiations taking place in IOs and regimes. Thus, International Relations scholarship offers a rich account of theories of international cooperation in general and of negotiation approaches in particular. This section draws on this body of literature in order to develop hypotheses on satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes that relate to features of the actors themselves (actor characteristics on the individual and the country level), features of the international negotiation context (IO characteristics) and interlinkages between these elements.

Much of the scholarship on international cooperation and negotiations can be distinguished alongside a rationalist-constructivist divide (Wendt 1992; Oakeshott 1991; Johnson 1993; Martin 1993; Levy 1997; Snidal 2002 Ruggie 1998; Fearon and Wendt 2002; Risse 2002; Hurd 2008; Checkel 1998, 2004). While the former assumes that states operate as strategic rationalist actors and use their power to pursue their positions on the basis of bargaining, the latter assumes that actors pursue their position on the basis of debates in which the power of the better argument prevails and can even lead to changes in positions and interests of actors involved (Müller 2004; Evans et al. 1993; Elgström and Jönsson 2000; Falkner 2000; Bailer 2004; Magnette 2004). Empirical studies have demonstrated that both ontological assumptions are useful, since both forms of interaction take place in real-life negotiations within IOs (Elster 1992; Risse 1999, 2000; Holzinger 2004; Deitelhoff and Müller 2005): Debates entail elements of bargaining, in which actors seek to push their positions by voicing demands, promises, concessions and implicit threats (e.g. unilateral actions, no-vote threats), as well as elements of arguing, in which actors voice their positions linked to technical, legal, factual, scientific or normative reasons. Thus, we capture both dynamics in our hypotheses and turn the prevalence of argumentative versus bargaining-based dynamics and corresponding actor orientations into an empirical rather than an ontological question (c.f. hypothesis 8a and 8b; interaction hypotheses 1a-2b).

International negotiations are often complex and time intensive as negotiations do not only take place in the formal arenas (working groups, committees, Conferences of the Parties), but also in informal settings, such as coffee breaks, lunches, receptions, or workshops. In all these contexts, delegates can use a broad array of multilateral and bilateral strategies in order to promote their national positions (Habeeb 1988; Odell 2000; Reardon 2004; Dür and Mateo 2010b; Panke 2013; Panke, et al. 2018). As activity is likely to be conducive to success, we expect: The more work a delegate puts into pursuing the national position, the greater are the chances to succeed in shaping the negotiation outcome (hypothesis 1).

National positions are usually developed in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFAs) or line ministries in the capitals back home and subsequently sent to the national delegations at the IO negotiation table (Kassim et al. 2000; Panke 2010). These instructions differ in the room of maneuver to conduct the negotiations that they provide the actors with (Kassim, et al. 2000). Some diplomats have little leeway in how to conduct negotiations as their instructions entail the speaking points and outline the negotiation strategy to be adopted (Mo 1995; Tsebelis 2002), while others might be equipped with instructions that leave them great flexibility to respond to and shape negotiation dynamics as they evolve. Actors with higher levels of flexibility in how to conduct the negotiations are more likely to be successful in negotiations, not only because they might be able to avoid delays and periods of inactivity at the negotiation table resulting from the need to wait for responses from the capital or the failure of the capital to provide updates at all (Panke 2013). Thus, flexible actors tend to be in a position in which they can be more active in general, as they can make use of more opportunities to engage with other delegates, and this activity can translate into better prospects for negotiation success. Hence, hypothesis 2 states: The higher the room for maneuver a state delegate has in how to conduct international negotiations, the greater the chances that he or she is satisfied with negotiation outcomes.

While actors are formally equal in most IOs (Keohane 1989), they nevertheless differ with respect to the bargaining power they bring to the negotiation table (Axelrod 1984; Habeeb 1988; Keohane 1989; Tallberg 2008; Zartman and Rubin 2009; Dür and Mateo 2010a; da Conceição-Heldt 2014). The more powerful a state, the better are its unilateral alternatives to multilateral cooperation and the greater their chances to obtain concessions by voicing bargaining threats (Axelrod 1984; Keohane 1989; Keohane and Nye 1989; Kremenyuk 1991; Odell 2000; Zartman and Rubin 2009). Moreover, actors from powerful states can use their economic financial wealth in order to offer side-payments or facilitate package deals as means of making concessions and compromises (Habeeb 1988; Pruitt 1991; Plantey 2007; Zartman and Rubin 2009). Finally, economic financial wealth usually associated with state power is a useful negotiation asset in an indirect manner: actors from wealthy states are usually well-equipped with respect to administrative and other support in multilateral negotiations and can often rely on the backing of a large delegation, whilst actors from weak states are more often on their own or supported by considerably smaller teams (Zartman and Berman 1982; Panke 2013). All of this can impact the chances of actors to successfully pursue their positions in international negotiations that reflect bargaining dynamics (all three pathways) and argumentative dynamics (third pathway). Thus, we expect: The more power a state has, the greater the chances that its delegate is satisfied with negotiation outcomes in an IO (hypothesis 3).

International negotiations are often time and work-intensive, whereby multiple aspects and issues are at the negotiation table at once (Kremenyuk 1991; Watkins 1999; Plantey 2007; Blavoukos and Bourantonis 2011). IOs often cope with packed negotiation agendas through a horizontal division of labor by which different agenda items are pre-negotiated in different committees or working groups. Thus, it is essential that delegates receive their positions and instructions form the capitals in due time (Laffan 1998). In case instructions arrive with a delay or not at all, delegations do not know which position to push in the IO and cannot meaningfully take part in the negotiations (Panke 2013). This is problematic since many of the issues on the IO agenda are usually resolved by the time the Conference of the Parties (CoP) starts (Habeeb 1988; Stein 1989; Prizeman 2012). Hence, the better the domestic policy formulation apparatus functions, and the quicker the Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MAF) or line ministries are in developing national positions and passing the instructions on to their delegations at the IO negotiation table, the earlier national delegates can push the national position in the international negotiation arena, and the greater are the chances that they succeed in influencing the negotiation outcome that is in line with their national position. Vice-versa, delegations from countries in which the domestic formulation of policy does not work swiftly and effectively are more often in a situation in which they have no instructions at the beginning of negotiations and have therefore fewer opportunities to influence the negotiation outcome accordingly. Hence, we expect: The more effective the domestic policy development apparatus works, the greater the chances that its delegate is satisfied with negotiation outcomes in an IO (hypothesis 4).

In addition to actor characteristics, factors located on the IO-level might also influence the extent to which actors are satisfied with negotiation outcomes.

IOs differ in size as some have fewer than 20 member states, while others are very encompassing with 190 and more states (Martin and Simmons 2001; Orsini 2014). For almost every item on the negotiation agenda of an IO, states already have domestic rules, regulations or norms in place that either directly or indirectly relate to the issue at stake. Consequently, the more states are sitting at an IO negotiation table, the greater is the number of different positions that need to be taken into consideration during the negotiations. Accordingly, in negotiation contexts with a higher number of actors, it is increasingly likely that actors have to make more concessions or have to compromise more strongly than in smaller IOs in which the diversity of positions is lower. Hence, the chances that an actor regards a negotiation outcome as strongly reflecting the national position decreases the larger IOs are in size (hypothesis 5).

Similarly, voting rules might impact outcome satisfaction. While almost all IOs are based on the notion of sovereign equality between the states (Hurd 2011), IOs differ concerning whether or not they allow for majority decisions or require unanimity in order to pass international rules and norms (McIntyre 1954; Posner and Sykes 2014). When majority voting is possible, it can happen that some states are outvoted (Hosli 1995; Hooghe and Marks 2014). This is not possible under conditions of unanimity, in which defector each member state holds a veto position. Therefore, we expect: if an IO does not allow for majority voting, outcome satisfaction increases (hypothesis 6).

Two additional institutional design features might be important: rules that seek to create room and time for debates between the actors, and rules that allow for the interruption of debates (Panke et al. 2019). The former should increase outcome satisfaction as it provides a context in which states can formally engage with each other and push their respective national positions – either through argumentative or based on bargaining-oriented strategies. By contrast, IOs with institutional designs that seek to delimit opportunities for exchange between diplomats in order to increase the speed of negotiations should lead to a decrease in the extent to which actors regard their own positions reflected in the final negotiation outcome as the opportunities to work towards consensual outcomes or construct compromises that encompass all or almost all actors are reduced the more restricted debates are. Consequently, we expect that IOs’ institutional designs that seek to foster debates should increase the outcome satisfaction of actors (hypothesis 7a). Vice-versa, IO institutional designs that allow for interruptions of debates should reduce the outcome satisfaction of actors (hypothesis 7b).Footnote 3

Scholarship on interactions in international negotiations distinguishes between whether actors predominantly operate in a bargaining context, exchanging positions linked to explicit or implicit threats, make demands and concessions, or whether a more argumentative mode is at play in which actors also articulate their positions and seek to influence the negotiation outcome, but do so in exchanging legal, factual, scientific, technical, political or normative reasons for and against certain problem solutions (Fischer and Forester 1993; Müller and Risse 2001; Fischer 2003; Johnstone 2003; Deitelhoff and Müller 2005; Koskenniemi 2006). Thus, bargaining tends to create winners and losers and lowest common denominator outcomes, whereas arguing tends to lead to an upgrading of common interests and more demanding outcomes (Elster 1992; Moravcsik 1993; Fearon 1998; Lewis 1998; Schoppa 1999; Busch and Reinhardt 2003; Dür and Mateo 2010a). Although we now know that both modes take place in multilateral negotiations, not all negotiations might be equally characterized by arguing and bargaining dynamics, as it might happen that one mode is more prevalent than the other. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypotheses: The higher the extent of arguing in an IO, the more satisfied actors are with negotiation outcomes in this context (hypothesis 8a). Vice-versa, the higher the extent of bargaining in an IO, the less satisfied actors are with negotiation outcomes in this context (hypothesis 8b).

In addition to hypotheses on actor and IO characteristics, we also explore cross-level interactions. Rather than formulating 36 interaction hypotheses linking each actor factor to each context factor for two different outcome variables each (high and moderate satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes), we are more selective. We focus especially on whether the effect of actor flexibility on outcome satisfaction is moderated by the institutional design features as this individual-level variable has the largest effect size (see Table 2). In addition, the flexibility variable is included in all regression models as it is not highly correlated with any of the individual, country or IO level features. As the dependent variable, outcome satisfaction, is an ordered count variable, we specify a hypothesis for one of the outcomes only (high success; outcome 5) for each interaction between actor and institutional context features. We selected high success, since we are most interested in the underlying dynamics of high outcome satisfaction. In addition, in the appendix, we also specify one hypothesis for moderate success (outcome 3) for each interaction between actor and institutional context features and report the results.

First, we shed light on how the effect of actor flexibility to conduct negotiations on their outcome satisfaction might be moderated in IOs in which argumentative dynamics are strongly at play. When mainly argumentative dynamics are at play in an IO, actors voice principled positions that are linked to reasons to persuade third party actors to take a point on board and change the negotiation outcome accordingly (Elster 1992; Risse 1999; Holzinger 2004; Müller 2004; Deitelhoff and Müller 2005). Yet, in order to engage in such debates, actors need flexibility in order to respond to one another (Perloff 1993; Cruz 2000; Checkel 2002; Deitelhoff 2009). Delegates that have much flexibility to negotiate without having to ask their line ministry in the capital for new or changed instructions or positions for each and every position adjustment are more likely to participate meaningfully in argumentative debates and thereby increase their chances of influencing the negotiation outcome and being satisfied with the latter. Thus, when arguing takes place in a negotiation, actor flexibility has a positive effect on outcome satisfaction as it allows delegates to meaningfully respond to each other instead of talking at cross purposes, and this effect is the more pronounced the stronger the argumentative dynamics in an IO is. Therefore, the first interaction hypothesis is: Actors who are relatively more flexible in how to conduct negotiations have a higher probability of being very successful (outcome 5) and the positive effect of flexibility is more pronounced the more the negotiation context is characterized by arguing (hypothesis I-1).

Second, the negative effect of actor flexibility on outcome satisfaction that can be expected under conditions of bargaining, might be moderated by institutional contexts in which bargaining dynamics are strongly at play. Under conditions of bargaining, however, inflexibility becomes an asset. Actors with high levels of flexibility cannot recur to the full array of bargaining strategies. Most notably, using the tied hands strategy, by which actors signal that they cannot move towards others as they cannot change or adapt their positions, cannot credibly be applied and lose their effectiveness (Putnam 1988; Knopf 1993; Mo 1995). Vice-versa, actors that are bound by tight instructions can use this ‘limitation’ as an asset to obtain concessions of third party actors (Lehman and McCoy 1992; Paarlberg 1997). Thus, the latter type of actors should be more successful in negotiations mainly characterized by bargaining dynamics. In other words: Inflexibility can be an asset when bargaining takes place. Accordingly, the second interaction hypothesis states: Highly flexible delegates have a higher probability of being very successful than delegates that operate following tight instructions (outcome 5) and the positive effect of flexibility decreases the more the negotiation context is characterized by bargaining (hypothesis I-2).

Apart from interaction dynamics at play in IOs, IO institutional design could also impact how actor characteristics play out with respect to outcome satisfaction. IO size, IO voting rules, IO rules promoting debates between diplomats and IO rules allowing for the interruption of debates could reinforce or delimited the effect of flexibility on outcome satisfaction.

The larger IOs are in size, the more actors are at the negotiation table. An increase in membership size could reduce the positive effect of high flexibility in conducting negotiations on being very successful. In larger IOs the number of positions that need to be taken into account for a negotiation outcome to pass increases (Axelrod and Keohane 1986). This, in turn, increases the chances that each actor has to move from its initial ideal position (Tsebelis 2002). Accordingly, we expect the following: A higher flexibility of delegates is conducive to a higher probability of being very successful (outcome 5) which becomes less pronounced the larger IOs are (hypothesis I-3).

Voting rules might also impact outcome satisfaction, as consensus or unanimity requires to accommodate all actors to some extent (Mattila and Lane 2001; Hurd 2011; Rittberger et al. 2012). This is particularly beneficial to inflexible actors, who have a higher likelihood to be accommodated under unanimity rule and should, therefore, be increasingly satisfied with a negotiation outcome if IOs operate on unanimity rather than majority voting. Accordingly, the fourth interaction hypothesis states: In general, high flexibility actors have a greater likelihood of being successful than inflexible actors (outcome 5) and this effect is reduced if IOs operate on the basis of unanimity rules instead of majority voting (hypothesis I-4).

Finally, the focus is on how institutional rules seeking to promote debates and seeking to shorten them modify the positive impact of flexibility on being satisfied with outcomes achieved in IO negotiations. Institutional design rules that are geared towards shortening discussions amongst national delegates reduce the opportunities of the actors to pursue their positions in the IO. This should reduce the positive effect of high flexibility on outcome satisfaction since flexibility in how to conduct negotiations can only pay off if negotiation dynamics can unfold freely. Vice-versa, Institutional design rules promoting debates create more chances for discussions amongst the actors and increase thereby their opportunities to make their voices heard and influence the negotiation outcome. Under such rules, the positive effect of high flexibility on the dependent variable should be further amplified. Thus, we formulate the following two sets of interaction hypotheses: Actors who are relatively more flexible in how to conduct international negotiations have a higher probability of being very successful (outcome 5) and the positive effect of flexibility is more pronounced for such actors the more the IO institutional design seeks to promote debates (hypothesis I-5). Higher flexibility of actors is conducive to a higher probability of being very successful (outcome 5) which becomes less pronounced the more IO institutional design is geared towards shortening discussions (hypothesis I-6).

4 Empirical analysis and discussion

The dependent variable of this paper is the extent of satisfaction of delegates with the final outcome. Data for the dependent variable stems from our 2019 survey (c.f. Section 2). The variable is categorical in nature and can conceptually range between one and five in an ordinal manner. In addition, we have variables measured at three different levels in our models; namely individual-, country-, and IO-level. However, while we have a clustering pattern at IO-level (i.e. country officials nested in different IOs), we do not have a clustering pattern at the country level as there are not enough observations per county in each of the IOs. Thus, in accordance with the nature of the data, we do not observe any substantial and significant changes in the results when we incorporate country-level random effects in addition to IO-level in our multilevel models. Therefore, all of our models include IO random effects to account for possible non-independency of the responses for the same IO. With respect to the empirical analysis of the hypotheses, we opt for mixed-effect ordered logit regression, which suits the best considering the ordinal nature of our dependent variable as well as the hierarchical structure of data.

The independent variables are measured on three different levels and data come from various sources (for summary statistics, c.f. Table A3). The independent variables for the first two hypotheses which concern the individual characteristics are measured by two items of our 2019 survey. For the first hypothesis, respondents indicated the extent of the “workload” for national delegations on a five-point scale. For the second hypothesis, a similar measure was used in order to capture the degree of “flexibility” that delegates have in debates.

Data for the country-level hypotheses stem from the World Development Indicators (WDI) and Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) datasets compiled by the World Bank. For hypothesis 3, state power is measured by a proxy variable: “GDP” in constant 2010 US billion dollars. “Government effectiveness” is used as a proxy for hypothesis 4 which captures the quality of policy formulation and implementation as well as the government’s commitment to such policies.Footnote 4 This variable can range empirically between −2.5 and 2.5.

For our IO-level independent variables, we have mainly drawn on data from a novel dataset that constitutes numerous measures on IOs’ institutional characteristics (Panke et al. 2019). For hypothesis 5, “IO size” counts the number of member states with full membership rights in 2016 based on the official IO websites. For the marginal plots (Graph 3 and A1) we divided this variable by ten in order to accommodate problems of not converging models stemming from the wide gap between the highest and lowest value of the variable IO size in the dataset. “Consensus rule” is the independent variable for hypothesis 6. It is measured by a dummy variable which is coded one if IO institutional design arranges decisions to be exclusively or predominantly taken by unanimity in the main decision-making arena and coded zero otherwise. Data for hypothesis 7a is based on a composite measure that captures the extent of IO institutional design geared towards fostering debates between delegates (e.g. by allowing for proposals or amendments by individual actors, allowing for exceptions concerning the timing of proposals, the withdrawal of proposals or amendments and the reintroduction of withdrawn or rejected items). The variable “fostering debates” can range between 0 and 1 in a continuous manner. For hypothesis 7b, we have drawn on another continuous variable that measures to what degree IO institutional design allows for interruptions of debates (e.g. granting individuals the right to interrupt discussion, allowing delegates to close the debate on a specific item, and to close the meeting). The variable “interruptions of debates” can range empirically between 0 and 1. Independent variables for hypothesis 8a and 8b are the “extent of arguing” and the “extent of bargaining”, respectively, and both are based on data from the survey. The corresponding survey items ask the respondents to report to what extent arguing as well as bargaining takes place in a given IO on a five-level scale. Bargaining is characterized by actors seeking to push their positions by voicing demands, promises, concessions and implicit threats (e.g. unilateral actions, no-vote threats), while arguing is characterized by actors voicing their positions linked to technical, legal, factual, scientific or normative reasons. Then, the mean value of both items (i.e. arguing and bargaining) are calculated for each IO.

shows that the chances of being moderately successful are lower for delegates that can flexibly and actively conduct negotiations than delegates that operate on the basis of tight instructions and this probability decreases the more arguing takes place in IO debates (hypothesis I 1 moderate success). Hypothesis I 2 on moderate success is plausible in some respects. Increasing bargaining dynamics in an IO context increase the chances of highly flexible actors to be moderately satisfied with outcomes. Yet, bargaining does not have the same moderating effect on actors without much flexibility as the line is not linear. Hence, bargaining has a different moderating effect for highly flexible actors than for inflexible ones. An increase in IO size only slightly increases the probabilities for moderate outcome satisfaction for delegates that can and that cannot flexibly conduct negotiations (hypothesis I 3 moderate success). There is also support for hypothesis I-4 on moderate success. High flexibility delegates are more likely to be moderately successful when IOs operate on the basis of unanimity instead of majority voting. Hypothesis I-5 on moderate success has to be rejected. Inflexible actors behave in a non-linear manner with respect to moderate outcome satisfaction when the extent to which IO design seeks to induce debates increases. For HI 6 on moderate success, the moderating effect of IO institutional design varies between highly and hardly flexible actors. While the chances of being moderately successful increase for highly flexible delegates the more interruptions of negotiations are possible (in line with hypothesis I 6 moderate success), yet the chances of being moderately successful increase with IO institutional designs geared towards shortening discussions for inflexible actors

In the first step of our statistical analysis, we shed light on the plausibility of the first eight hypotheses and examine the interaction hypotheses in a second step. All models are parsimonious and free from a multicollinearity problem as they do not entail strongly correlated variables in one and the same model (such as consensus rule and interruptions of debates, or IO size and bargaining).Footnote 5 Table 2 indicates that many but not all theoretical expectations hold.

Table 2 lends support to both individual level hypotheses. Models 1 and 2 feature positive and highly significant covariates with respect to the workload of individual delegates. Thus, in line with hypothesis 1, delegates are more satisfied with IO negotiation outcomes, the more work they put into the corresponding negotiations. A second individual level feature is of high importance. The more flexible delegates are in how to conduct negotiations the more active they are and the stronger their satisfaction with outcomes. As the sign is robustly positive for all models and highly significant as well (Models 1–5, Table 2), we can reject the null hypothesis in favor of hypothesis 2.

The hypotheses on the country level reveal interesting insights. Hypothesis 3 expects that delegates from more powerful states have higher chances of being satisfied with the negotiation outcome. While the sign of the power variable is positive in all models, it is only significant in models 3 and 5. Thus, an increase in state power in tendency improves a delegate’s prospect to be satisfied with the outcomes in international negotiations. By contrast, diplomats are not more easily satisfied with international negotiation outcomes if they are from states with efficient government apparatus for the development of policy positions. As the models indicate that the coefficient is not robust and insignificant, hypothesis 4 has to be rejected.

On the IO level, hypothesis 5 is plausible. As expected, delegates are less satisfied with negotiation outcomes larger the IOs’ negotiation settings are, and the findings are significant in both models (Models 1 and 2). By contrast, hypothesis 6 has to be rejected as a consensus rule for arriving at decisions does not significantly increase outcome satisfaction in the corresponding IO (Model 3). The extent to which IO institutional design seeks to foster diplomatic debates matters as models 3 and 5 robustly feature appositive sign and are significant. In line with hypothesis 7a, delegates are more satisfied with negotiation outcomes if IOs provide many opportunities for introducing and modifying proposals in a dynamic manner and thereby induce debates. Vice-versa, hypothesis 7b expects that IOs with institutional rules that allow for interrupting negotiations feature lower levels of outcome satisfaction. In accordance with hypothesis 7b, models 1 and 4 report negative and significant coefficients. Hypothesis 8a and b zoom in on the nature of debates taking place in IOs. Hypothesis 8a expects that outcome satisfaction increases the stronger debates reflect arguing. While the signs are robustly positive in models 1, 2 and 4, neither finding is significant and hypothesis 8a needs to be rejected. By contrast, hypothesis 8b is plausible. The more debates are characterized by bargaining dynamics, the less satisfied delegates tend to be (Models 3 and 5, Table 2).

In sum, we find that many individual and IO factors impact outcome satisfaction in a systematic manner, while only one country level factor impacts outcome satisfaction in tendency if one controls for individual and IO level variables at the same time. Most importantly, delegates are increasingly successful the more work they put in negotiations, the more flexible they can conduct negotiations, if they are from powerful states (in tendency), and if the negotiations take place in an IO which is small in size, induces debates between delegates whilst preventing frequent interruptions, and in which international negotiations are not strongly characterized by bargaining.

In a second step, we examine the cross-level interaction effects specified in the theoretical section. The marginal plots for the interaction hypotheses on high outcome satisfaction are depicted in Graph 3 (for results on moderate outcome satisfaction, c.f. Appendix Graph A1).Footnote 6

The interaction plots show that delegates with high flexibility are overall more likely to be highly satisfied with negotiation outcomes than delegates that operate with strings attached (Graph 3). A glance into the six different IO-level modifying factors reveals mixed findings for the interaction hypotheses.

The upper left plot illustrates that in tendency highly flexible actors are more satisfied with outcomes, if arguing gets more pronounced in a negotiation context. Thus, the more technical, legal, factual, scientific or normative reasons are exchanged during negotiations, the more satisfied actors become with the outcome – especially if they themselves have room for maneuver to get actively involved in these discussions.

The upper-middle plot shows that as bargaining dynamics become more prevalent in negotiations, this reduces the satisfaction with negotiation outcomes of delegates with high flexibility. This reflects that tied-hands strategies matter in bargaining situations, by which actors with inflexible negotiation approaches can leverage up. In such two-level game situations, highly flexible actors benefit less from their flexibility and are therefore decreasingly successful.

Compared to the first two interactions, the observed patterns in the latter four plots are less defined. Highly flexible actors tend to be less satisfied with negotiation outcomes, the larger IOs are as depicted in the upper right plot. In larger IOs the number of actor positions to be taken into account increases, which requires more concessions and compromises to be made and moves the outcome towards the lowest common denominator. This reduces the outcome satisfaction in tendency.

Moving to the lower left plot, consensus rule in IO decision-making only slightly reduces the satisfaction with outcomes for highly flexible actors, compared to IOs that allow for majority voting. Yet, the modifying effect of this institutional rule on outcome satisfaction is not nuanced.

While the plots were in line with the respective directionality of the interaction effects as specified by all interaction hypotheses discussed so far, this is not the case for hypothesis I 5. The institutional rules geared towards fostering debates between delegates hardly modify the effects of actor flexibility. Yet, the lower middle plot illustrates that if there is increasingly much room for diplomatic exchanges, this reduces the outcome satisfaction in tendency. This runs against the expectation of hypothesis I 5.

Finally, the lower right plot allows studying whether institutional rules disrupting debates between delegates modify the outcome satisfaction. Highly flexible actors are somewhat less satisfied with outcomes the more the IO institutional design allowed for frequent disruptions of negotiations, as this prevents these delegates from putting their leeway in how to conduct negotiations to work.

Apart from bargaining (hypothesis I 2), none of the modifying effects reaches the conventional levels of significance. Since there are lower numbers of observations with respect to extreme values, the error bonds increase towards extreme values. Although the interaction effects of hypothesis I 1, I 3, I4 and I 6 are in line with the expected direction, they should be interpreted cautiously.

5 Conclusions

Satisfaction with negotiation outcomes is important in several respects and for several strands of research. First, international norms and rules are most often results of international negotiations and matter for states either because of their hard law status and the high legalization of the IO in which the negotiations took place or because of informal logics of appropriateness resulting from soft law status of norms (e.g. Abbott and Snidal 2000; Alvarez 2005; Dunoff and Trachtman 2009; Armstrong et al. 2010). Thus, numerous studies have traced how international rules and norms affected state conduct in policy areas as diverse as security and disarmament (e.g. Cooper 2006; Lodgaard and Maerli 2007; Stavrianakis 2016), environmental protection (e.g. Keohane et al. 1993; Peterson 1997; Young 1999), or human rights (e.g. Schmitz and Sikkink 2002; Forsythe 2006; Simmons 2009; Hafner-Burton 2012; Von Stein 2016). Second, studying determinates of outcome satisfaction is important as it provides insights into who is more and who is less successful in influencing the content of international norms and rules. Third, satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes and state compliance might be linked, as states that support a specific rule or norm have great incentives to obey it in practice as well (e.g. Levy et al. 1993; Jacobsen and Brown 1995; Cameron et al. 1996). While there is a large body of negotiation literature focusing on a few specific features in qualitative studies or on country level variables in large-N studies, so far no study has researched in an encompassing manner how individual-, country- and IO-level variables impact outcome satisfaction jointly. Moreover, so far there are no studies looking at cross-level interactions for a large number of individual delegates, of states and of IOs.

This paper seeks to make a contribution in examining three levels as it analyses whether and which individual, country and IO features contribute to satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes. Most importantly, we show that individual and IO level features matter in a significant manner for outcome satisfaction. On the individual level, the amount of work delegates put in and the flexibility they have to conduct negotiations increase the extent to which actors see their position reflected in the outcome. On the country level, capacities to formulate policy positions do not translate into higher probabilities for outcome satisfaction and, in tendency state power increases the success of a delegate in IO negotiations. On the IO-level, several factors are of importance. Limited IO size and IO institutional design rules fostering debates between delegates and preventing interruptions increase average outcome satisfaction. In addition, if IO negotiations are not characterized by bargaining dynamics, outcome satisfaction increases. At the same time, the voting rule (majority versus consensus) and the extent of arguing in debates does not systematically increase the satisfaction with negotiation outcomes. In short, delegates should be most satisfied with outcomes that are negotiated in small IOs with rules promoting the continuation of debates and preventing interruptions and in which bargaining is rare. In addition, outcome satisfaction increases in tendency if delegates come from powerful states and considerably if delegates put much work into negotiations and are flexible in how they conduct the negotiations rather than being bound by tight instructions.

Moreover, this study shows that overall delegates are more satisfied with outcomes the more flexible they can conduct negotiations and this is somewhat moderated by the institutional context in which they operate. Not all IO institutional design features play the same role in this respect. The positive effect of flexibility on high outcome satisfaction is less pronounced when negotiations are more strongly characterized by bargaining dynamics. The same directionality applies to the moderating effects of IO size, inducing debates through proposals, preventing interruptions, and unanimity rule, but is much less pronounced. By contrast, the positive effect of conducting negotiations flexibly on high outcome satisfaction is in tendency more pronounced when negotiations are more strongly characterized by arguing dynamics. Moreover, while the directionality of the moderating effect tends to be the same for highly flexible as well as inflexible actors, it is reversed for bargaining dynamics, IO rules inducing dynamic debates and IO rules on unanimity in decision-making. In these three settings, an increase in the moderating factors tends to reduce the gaps between delegates with high and with low flexibility with respect to being highly satisfied with negotiation outcomes.

Our study has illustrated that integrating the individual, the country and the IO level into a comprehensive analysis adds value to the understanding of international negotiations by examining all three levels in conjunction. This approach could also be applied to a range of different international relations phenomena in future research, since much of the current work on cooperation and conflict focuses on the country- and/or the international level only, disregarding factors located on the individual level and rarely looking at interactions between these levels.

Compliance research has illustrated that two components, capacity and willingness play a crucial role for the chances that a state complies with international norms and rules (Fisher 1981; Mitchell 1996; Chayes, et al. 1998; Cremona 2012; Risse et al. 2013). For the latter part, satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes can play an important role. The more satisfied states are with the result of international negotiations, the greater the chances that they are willing to comply afterward with the resulting norms and rules. This paper proposes that future research examines more closely the interlinkages between outcome satisfaction, compliance and problem-solving effectiveness of IOs. This issue is not only interesting from a scholarly point of view, but also carries high policy relevance.

Our study suggests that there are several features which can improve outcome satisfaction and might thereby also increase the ex-post commitment to the negotiation outcomes. First, as smaller IOs feature higher levels of outcome satisfaction than larger ones, states should place great emphasis on cooperation in regional international organizations rather than exclusively relying on global ones. Yet, since global IOs are broader in reach, it is important that states do not downplay their participation in these IOs at the same time. Second, IOs’ rules of procedure that are geared towards creating time and space for debates between delegates tend to be conducive to higher outcome satisfaction and should therefore be preferred over institutional designs that curb debates short in order to reduce the time for negotiations. Third, satisfaction with international negotiation outcomes increases if delegates are equipped with sufficient time and resources to pursue their national positions. The feasibility of these three recommendations for an individual government varies. While individual states can decide autonomously how much room of maneuver they want to equip their national delegates with, joining regional IOs is not only a lengthy process, the prospective new member state is also usually not in control of the outcome. Finally, in order to change the rules of procedures of IOs, IO treaties usually require consensus amongst the member states, thus reducing the feasibility of realizing institutional design changes autonomously.

Change history

18 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09430-4

Notes

We distinguished the main legislative body from judicial, executive, and consultative bodies. The main legislative arena provides a floor for actors to discuss and decide upon IO policy outcomes, such as resolutions, regulations, norms, and other types of hard and soft law.

Thus, the survey question was intentionally framed in a manner to only capture the outcome satisfaction with respect to the national interests at stake. Through this cross-checked phrasing, we avoided ambiguity in measurement, concerning, for instance, other elements that might influence individual perceptions of satisfaction, such as the extent to which he/she thinks that the final negotiations outcome contributes to solving the underlying collective action or policy problem.

These two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive but can be complementary. In theory, an IO institutional design can embody many rules that foster debates and at the same time also incorporate many rules that allow for disruptions of debates ({Panke, 2019 #8901}). A similar point can be made with respect to bargaining and arguing (H8 a and b).

The World Bank states that it is measured by the “quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies” (https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/government-effectiveness-estimate-0).

A correlation table is available upon request.

Comparing the findings for high and moderate outcome satisfaction reveals that the respective cross-level interaction hypotheses are either both plausible or both rejected and that the effects that can be evidenced for high success have – as expected in theory – the opposite directionality (c.f. Appendix).

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2000). Hard and soft law in international governance. International Organization, 54, 421–456.

Albin, C., & Druckman, D. (2014). Procedures matter: Justice and effectiveness in international trade negotiations. European Journal of International Relations, 20, 1014–1042.

Alvarez, J. E. (2005). International organizations as law-makers. Oxford: Oxford University Press Oxford.

Archer, C. (2014). International organizations. London: Routledge.

Armstrong, D., Farrell, T., & Lambert, H. (2010). International law and international relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Axelrod, R. A. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

Axelrod, R. A., & Keohane, R. O. (1986). Achieving cooperation under anarchy: Strategies and institutions. World Politics, 38, 226–254.

Bailer, S. (2004). Bargaining success in the European Union. European Union Politics, 5, 99–123.

Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. London: Cornell Cornell University Press.

Bazerman, M. H., Curhan, J. R., & Moore, D. A. (2001). The death and rebirth of the social psychology of negotiation. In G. J. O. Fletcher & M. S. Clark (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes (Vol. 196, p. 228). London: Wiley.

Beck, R. J., Arend, A. C., Vander, R. D., & Lugt. (1998). International rules. Approaches from International Law and International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bercovitch, J. (1992). Mediators and mediation strategies in international relations. Negotiation Journal, 8, 99–112.

Blavoukos, S., & Bourantonis, D. (2011). Chairing multilateral negotiations: The case of the United Nations. London: Routledge.

Busch, Marc L., Reinhardt, Eric. 2003. Bargaining in the shadow of the law: Early settlement in GATT/WTO disputes.

Cameron, J., Werksman, J., & Roderick, P. (Eds.). (1996). Improving compliance with international environmental law. London: Earthscan.

Carlsnaes, W., Risse-Kappen, T., Risse, T., & Simmons, B. A. (2002). Handbook of international relations. London: Sage.

Chayes, A., Handler-Chayes, A., & Mitchell, R. B. (1998). Managing compliance: A comparative perspective. In E. B. Weiss & H. K. Jacobsen (Eds.), Engaging countries: Strengthening compliance with international environmental accords (pp. 39–62). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Checkel, J. T. (1998). The constructivist turn in international relations theory. World Politics, 50, 324–348.

Checkel, J. T. (2002). Persuasion in international institutions. ARENA Working Papers WP, 02(14), 1–25.

Checkel, J. T. (2004). Social Constructivisms in global and European politics: A review essay. Review of International Studies, 30, 229–244.

Coleman, K. P. (2013). Locating norm diplomacy: Venue change in international norm negotiations. European Journal of International Relations, 19, 163–186.

Cooper, N. (2006). Putting disarmament back in the frame. Review of International Studies, 32, 353–376.

Cortell, A. P., & Davis, J. W., Jr. (2000). Understanding the domestic impact of international norms: A research agenda. International Studies Review, 2, 65–87.

Cremona, M. (2012). Compliance and the enforcement of EU law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cruz, C. (2000). Identity and persuasion: How nations remember their pasts and make their futures. World Politics, 52, 275–312.

Curhan, J. R., Elfenbein, H. A., & Eisenkraft, N. (2010). The objective value of subjective value: A multi-round negotiation study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 690–709.

da Conceição-Heldt, E. (2014). When speaking with a single voice isn't enough: Bargaining power (a)symmetry and EU external effectiveness in global trade governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 21, 980–995.

Deitelhoff, N. (2009). The discursive process of legalization: Charting Islands of persuasion in the ICC case. International Organization, 63, 33–65.

Deitelhoff, N., & Müller, H. (2005). Theoretical paradise - empirically lost? Arguing with Habermas. Review of International Studies, 31, 167–179.

Diehl, P. F., & Frederking, B. (2015). The politics of global governance: International organizations in an interdependent world. New York: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Druckman, D. (1983). Social psychology and international negotiations: Processes and influences. Advances in applied social psychology, 2, 51–81.

Dunoff, J. L., & Trachtman, J. P. (Eds.). (2009). Ruling the world?: Constitutionalism, international law, and global governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dür, A., & Mateo, G. (2010a). Bargaining power and negotiation tactics: The negotiations on the EU's financial perspective, 2007–13. Journal of Common Market Studies, 48, 557–578.

Dür, A., & Mateo, G. (2010b). Choosing a bargaining strategy in EU negotiations. Power, preferences and culture. Journal of European Public Policy, 17, 680–693.

Elgström, O., & Jönsson, C. (2000). Negotiating in the European Union: Bargaining or problem-solving? Journal of European Public Policy, 7, 684–704.

Elster, J. (1992). Arguing and bargaining in the Federal Convention and the Assemblée Constituanté. In R. Malnes & A. Underdal (Eds.), Rationality and institutions. Essays in Honour of Knut Midgaard (pp. 13–50). Oslo: Univeritetsforlaget.

Evans, P. B., Jacobson, H. K., & Putnam, R. D. (Eds.). (1993). Double-edged diplomacy: International bargaining and domestic politics (Vol. 25). Berkely: University of California Press.

Falkner, G. (2000). The council or the social partners? EC social policy between diplomacy and collective bargaining. Journal of Public Policy, 7, 705–724.

Fearon, J. D. (1998). Bargaining, enforcement and international cooperation. International Organization, 52, 269–305.

Fearon, J., & Wendt, A. (2002). Rationalism v. constructivism: A sceptical view. In W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse, & B. A. Simmons (Eds.), Handbook of international relationsq (pp. 52–72). London: Sage.

Fischer, F. (2003). Policy analysis as discoursive practice: The argumentative turn. In F. Fischer (Ed.), Reframing public policy (Vol. 9, pp. 181–202). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fischer, F., & Forester, J. (Eds.). (1993). The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fisher, R. (1981). Improving compliance with international law. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Forsythe, D. P. (2006). Human rights in international relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fowler, Jr, F.J. (2013). Survey Research Methods. London, Sage.

Habeeb, W. M. (1988). Power and tactics in international negotiation: How weak nations bargain with strong nations. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Hafner-Burton, E. M. (2012). International regimes for human rights. Annual Review of Political Science, 15, 265–286.

Holzinger, K. (2004). Bargaining through arguing: An empirical analysis based on speech act theory. Political Communication, 21, 195–222.

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2014). Delegation and pooling in international organizations. Review of International Organizations, 19(4), 773–796.

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2015). Delegation and pooling in international organizations. Review of International Organizations, 10, 305–328.

Hosli, M. O. (1995). The balance between small and large: Effects of a double-majority system on voting power in the European Union. International Studies Quarterly, 39, 351–370.

Hurd, I. (2008). Constructivism. In C. Reus-Smith & D. Snidal (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of International Relations (pp. 298–316). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurd, I. (2011). International organizations. In Politics, law, practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobsen, H. K., & Brown, E. W. (1995). Strengthening compliance with international environmental accords: Preliminary observations from a collaborative project. Global Governance, 1, 119–148.

Johnson, J. (1993). Is talk really cheap? Prompting conversation between critical theory and rational choice. American Political Science Review, 87, 74–86.

Johnstone, I. (2003). Security council deliberations: The power of the better argument. European Journal of International Law, 14, 437–480.

Kassim, H., Anand, M., Guy Peters, B., & Wright, V. (2000). The National co-ordination of EU policy. The domestic level. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keohane, R. O. (1989). International institutions and state power. Boulder: Westview.

Keohane, Robert O., Peter M. Haas, and Marc A. Levy. 1993. "The effectiveness of international environmental institutions." in Institutions for the Earth. Sources of Effective International Environmental Protection, eds. Peter M. Haas, Robert O. Keohane and Marc A. Levy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 3-26.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (1989). Power and Interdependence. Glenview: Scott, Foresman and Company.

Knopf, J. W. (1993). Beyond two-level games: Domestic-international interaction in the intermediate-range nuclear forces negotiations. International Organization, 47, 599–628.

Koskenniemi, M. (2006). From apology to utopia: The structure of international legal argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kremenyuk, V. (Ed.). (1991). International negotiation: Analysis, approaches, issues. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Laffan, B. (1998). Ireland: The rewards of pragmatism. In K. Hanf & B. Soetendorp (Eds.), Adapting to European Integration: Small States and the European Union (pp. 69–83). London: Longman.

Lehman, H. P., & McCoy, J. L. (1992). The dynamics of the two-level bargaining game. The 1988 Brazilian debt negotiations. World Politics, 44, 600–644.

Levy, J. S. (1997). Prospect theory, rational choice, and international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 41, 87–112.

Levy, Marc A., Robert O. Keohane, and Peter M. Haas. 1993. "Improving the effectiveness of international environmental institutions." in Institutions for the Earth: Sources of Effective International Environmental Protection, eds. Peter M. Haas, Robert O. Keohane and Marc A. Levy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 397-426.

Lewis, J. (1998). Is the ‘Hard Bargaining’ image of the council misleading? The Committee of Permanent Representatives and the local elections directive. Journal of Common Market Studies, 36, 479–504.

Lodgaard, S., & Maerli, B. (Eds.). (2007). Nuclear proliferation and international security. London: Routledge.

Magnette, P. (2004). Deliberation or bargaining: Coping with constitutional conflicts in the convention on the future of Europe. In J. E. Eriksen, J. Fossum, & A. Menendez (Eds.), Developing a constitution for Europe (pp. 207–225). London: Routledge.

Martin, L. L. (1993). The rational state choice of multilateralism. In J. G. Ruggie (Ed.), Multilateralism matters: The theory and practice of an international forum (pp. 91–121). New York: Columbia University Press.

Martin, L. L., & Simmons, B. A. (Eds.). (2001). International institutions. An international organization reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mattila, M., & Lane, J.-E. (2001). Why unanimity in the council? A roll call analysis of council voting. European Union Politics, 2, 31–52.

McIntyre, E. (1954). Weighted voting in international organizations. International Organization, 8, 484–497.

Mitchell, R. (1996). Compliance theory: An overview. In J. Cameron, J. Werksman, & P. Roderick (Eds.), Improving compliance with international environmental law. London: Earthscan.

Mo, J. (1995). Domestic institutions and international bargaining: The role of agent veto in two-level games. American Political Science Review, 86, 914–924.

Moravcsik, A. (1993). Introduction: Integrating international and domestic theories of international bargaining. In P. B. Evans et al. (Eds.), Double-edged diplomacy: International bargaining and domestic politics (pp. 3–42). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Morgenthau, H. J. (1948). Politics among nations. New York: McGraw Hill.

Müller, H. (2004). Arguing, bargaining and all that. Reflections on the relationship of communicative action and rationalist theory in Analysing international negotiations. European Journal of International Relations, 10, 395–435.

Müller, H., & Risse, T. (2001). Arguing and persuasion in multilateral negotiations. Grant Proposals to the Volkswagen Foundation." Schwerpunkt 'Globale Strukturen und ihre Steuerung'; Fassung August, 2001.

Naquin, C. E. (2003). The agony of opportunity in negotiation: Number of negotiable issues, counterfactual thinking, and feelings of satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 91, 97–107.

Novemsky, N., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2004). What makes negotiators happy? The differential effects of internal and external social comparisons on negotiator satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95, 186–197.

Oakeshott, M. (1991). Rationalism in politics. In M. Oakeshott (Ed.), Rationalism and politics and other essays (pp. 5–42). London: Liberty Press.

Odell, J. S. (2010). Three islands of knowledge about negotiation in international organizations. Journal of European Public Policy, 17, 619–632.

Odell, J. S. (2000). Negotiating the world economy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Oliver, R. L., Sundar Balakrishnan, P. V., & Barry, B. (1994). Outcome satisfaction in negotiation: A test of expectancy disconfirmation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 60, 252–275.

Orsini, A. (2014). Membership. The evolution of EU membership in major international organisations. In A. Orsini (Ed.), The European union with(in) international organisations. Commitment, consistency and effects across time (pp. 35–53). Farnham: Ashgate Globalisation, Europe, Multilateralism.

Paarlberg, R. (1997). Agricultural policy reform and the Uruguay round: Synergistic linkage in a two-level game? International Organization, 51, 413–444.

Panke, D. (2010). Developing good instructions in no time – An impossibility? Comparing domestic coordination practises for EU policies of 19 small and medium-sized states. West European Politics, 33, 769–789.

Panke, D. (2013). Unequal actors in equalising institutions. Negotiations in the United Nations General Assembly. Houndmills: Palgrave.