Abstract

Ceratocystis sensu stricto is a genus of closely related fungi that are mostly plant pathogens. Morphological variation between species in this genus is limited, and species delineation is strongly reliant on phylogenetic inference. Primary support for many of the species is based on the ITS region which, on its own, can be used to delineate all species described in the genus. However, the recent discovery of two ITS types in a single isolate of Ceratocystis questions the use of this marker in taxonomic studies. The aim of this study was to consider the potential use of alternative gene regions to support the species boundaries in this genus. The phylogenetic value of the βT 1 and EF 1-α gene regions, generally used in combination with ITS, were re-evaluated and compared to five single-copy protein coding genes (CAL, RPBII, MS204, FG1093 and Mcm7). As an alternative approach, genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified and evaluated as diagnostic markers to distinguish among the species. Fifteen species residing in Ceratocystis were used in this study. None of the protein-coding genes could be used to distinguish all species, but a combination of the βT 1, MS204 and RPBII gene regions resolved 11 of the 15 described species. Unique SNP markers were identified for 13 of the species, and these provided significant additional support for most of the established taxon boundaries. Other than ITS, none of the markers tested could distinguish between C. acaciivora and C. manginecans, and therefore these species are reduced to synonymy, with the name C. manginecans being retained. Results of this study also revealed the likely existence of additional species in Ceratocystis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A species can be defined as a group of individuals that have a unique evolutionary history and that have evolved independently from other lineages (Giraud et al. 2008). In the fungal kingdom, support for distinct species is based primarily on morphological, biological and phylogenetic characters (Cai et al. 2011; Taylor et al. 2000). However, the classical morphological species recognition approach lacks the capacity to distinguish between closely related taxa. Furthermore, biological species recognition is not possible for all fungi and it can be unreliable and misleading in laboratory environments (Harrington 2000; Taylor et al. 2000). During the course of the past 25 years, phylogenetic analysis and Genealogical Concordance Phylogenetic Species Recognition (GCPSR) has gained acceptance in the recognition of many new taxa that would not have been possible based on other criteria (Bridge et al. 2005; Rintoul et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2000).

Ceratocystis sensu lato (s.l.), an aggregate genus of insect-associated fungi, provides a useful example where the morphological, biological and phylogenetic species recognition criteria have been applied in taxonomic studies. The type species, Ceratocystis fimbriata, was described more than 120 years ago as the causal agent of root rot on sweet potatoes (Halsted 1890). Since then, 61 distinct species have been described in Ceratocystis s.l. based on a combination of various recognition criteria. The genus previously included various species complexes, generally well-supported by DNA-based phylogenies, morphological and ecological data (Mbenoun et al. 2013; Wingfield et al. 2013). Recently, phylogenetic inference based on multiple gene regions, as well as morphological and ecological data, has been used to define and describe these species complexes in discrete genera, of which Ceratocystis sensu stricto (s.s.) is one (De Beer et al. 2014). In this study, Ceratocystis is defined on this new taxonomic treatment and includes only those species previously treated as the Ceratocystis fimbriata sensu lato species complex.

Until the early 2000s, species of Ceratocystis s.s. were primarily defined based on unique morphological characteristics (Barnes et al. 2003; Kile et al. 1996; Upadhyay 1981; Wingfield et al. 1996). In some cases, identification has been supplemented using mating studies which, for example, could be used to confirm the species boundaries between C. fimbriata, C. platani and C. cacaofunesta (Engelbrecht and Harrington 2005; Ferreira et al. 2010). However, the recognition of the majority of cryptic species in Ceratocystis was based on DNA sequence data and phylogenetic inference (Van Wyk et al. 2011a; Wingfield et al. 1996). Since the incorporation of DNA sequence data for species delineation in 1996 (Wingfield et al. 1996), the majority of currently known species in Ceratocystis, as defined by de Beer et al. (2014), have been described based on phylogenetic inference using DNA sequence data.

Initial phylogenetic species delineation in Ceratocystis relied heavily on gene genealogies of the 5.8S and surrounding internal transcribed spacer regions 1 and 2 (ITS1 and ITS2) (Barnes et al. 2003; Roux et al. 2004). In an attempt to increase the resolution of species boundaries, sequences of the β-tubulin 1 (βT 1) and translation elongation factor 1-α (EF 1-α) gene regions have generally been used in combination with the ITS region for species delineation (Van Wyk et al. 2012, 2011b).

The Fungal Barcode of Life (FBoL) consortium has defined the ITS region as the barcode for fungal species identification (Schoch et al. 2012), although it is recognised that the region is not reliable for delineation of all species. Intragenomic ITS variation has been reported in single isolates of some fungi such as species of Fusarium (O’Donnell and Cigelnik 1997), Laetiporus (Lindner and Banik 2011), and more recently in a species of Ceratocystis (Al Adawi et al. 2013; Naidoo et al. 2013). In the case of Ceratocystis, the one ITS sequence obtained from an isolate was identical to that of C. manginecans, but the second ITS type differed by seven nucleotides and had the same sequence as C. acaciivora. Whether similar problems exist for all species in Ceratocystis has not been confirmed, although it has recently been suggested for species closely related to C. acaciivora and C. manginecans (Harrington et al. 2014).

Most of the cryptic species in Ceratocystis have been separated on the basis of genealogical concordance, but a few of these species have received the majority of the phylogenetic signal from the ITS region alone (Harrington et al. 2014; Tarigan et al. 2011; Van Wyk et al. 2011a, b). The two additional gene regions used in GCPSR, βT 1 and EF 1-α, contain limited variation and provide very low or no significant bootstrap support for these species. This situation occurs in species such as C. curvata, C. ecuadoriana, C. mangicola, C. mangivora, C. acaciivora, C. manginecans and C. eucalypticola (Tarigan et al. 2011; Van Wyk et al. 2012, 2011a, b).

Alternative gene regions that can be used for phylogenetic analysis of Ceratocystis species include regions used in fungal phylogenetic studies such as the Assembling the Fungal Tree Of Life (AFTOL) and FBoL projects (Seifert 2009; Spatafora 2005). These include the ribosomal small subunit (SSU), first and second largest subunits of RNA polymerase II (RPBI and II), ATP synthase 6 (ATP6), β-tubulin 2 (βT2) and Calmodulin (CAL) gene regions (O’Donnell et al. 2000; Spatafora 2005). In addition, various single-copy protein-coding genes, conserved in most fungi, have been identified from genome comparisons (Aguileta et al. 2008; Marthey et al. 2008). Genes among these that might be useful as phylogenetic markers include the pre-rRNA processing protein (Tsr1), minichromosome maintenance protein (Mcm7), 60S ribosomal protein L37 (FG1093) and guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-like protein (MS204) (Raja et al. 2011; Schmitt et al. 2009; Tretter et al. 2013; Walker et al. 2012b). The latter two have shown good potential to delineate closely related species.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that differ among species also provide opportunities as taxonomic markers. SNPs can occur at high frequencies in a genome and are more conserved than other polymorphisms, since they do not change the reading frame in coding regions (Fakhrai-Rad et al. 2002). Consequently, diagnostic SNP markers have been applied in a wide range of studies, for example on plants (Chouvarine et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013), animals (Garvin et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2013) and fungi (Pavlic 2009; Pérez 2010; Pérez et al. 2012) to distinguish among species.

There is a significant need for additional molecular markers to clearly and accurately differentiate among closely related species in Ceratocystis, especially due to their importance as plant pathogens. Many species in this complex are the cause of important diseases, including root rot, wilt and cankers, especially on trees but also on various root crops (Al Adawi et al. 2013; Engelbrecht and Harrington 2005; Halsted and Fairchild 1891; Kamgan et al. 2012; Tarigan et al. 2011; Van Wyk et al. 2010). The aim of this study, therefore, was to reassess the phylogenetic value of the βT 1 and EF 1-α gene regions for taxonomic purposes and, in addition, to consider the potential of additional genetic markers to distinguish between the species in this genus.

Materials and methods

Fungal isolates and DNA extraction

Isolates of 15 species in the Latin American clade of Ceratocystis (Mbenoun et al. 2013) were obtained from the culture collection (CMW) of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, South Africa. Species included C. fimbriata, C. cacaofunesta, C. manginecans, C. platani, C. acaciivora, C. colombiana, C. curvata, C. diversiconidia, C. ecuadoriana, C. eucalypticola, C. fimbriatomima, C. mangicola, C. mangivora, C. neglecta, and C. papillata. Two C. pirilliformis isolates were included as outgroups for the phylogenetic studies (Table 1). Depending on availability, between two and five isolates from different geographic locations and/or hosts were chosen per species, including the ex-type strain of each species. All isolates were grown in culture on 2 % malt extract agar (MEA) supplemented with 50 mg/l streptomycin (Sigma–Aldrich, Germany) and 100 μg/l thymine (Sigma–Aldrich, Germany).

For DNA extraction, mycelium was scraped from the surface of MEA plates and freeze-dried. Samples were crushed to a powder with sterile metal beads in a mixer mill type MM 301 Retsch® tissue grinder (Retsch, Germany). DNA was extracted using a phenol/chloroform method (Goodwin et al. 1992). Extracted DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 instrument (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA) and the quality assessed by gel electrophoresis on a 1 % agarose gel (AGE). For AGE, 5 μl DNA was combined with 2 μl GelRed™ (Biotium, California, USA) and the DNA visualized under UV illumination. DNA concentrations were standardized to a working dilution of 30 ng/μl for subsequent reactions.

Single-copy phylogenetic gene regions

Primer design PCR amplification and sequencing

Regardless of whether ITS sequence data were available on GenBank, amplification and sequencing of all isolates in this study was repeated to avoid discrepancies. The ITS1 and ITS4 primers (White et al. 1990) were used for amplification. Due to a long poly-A repeat in the sequence, primers ITS2 and ITS3 were used for additional sequencing of the internal regions in some isolates (White et al. 1990).

Seven additional gene regions were tested for amplification and for their potential use as phylogenetic markers in Ceratocystis. These were Mcm7, Tsr1, CAL, RPBII, βT 2, FG1093 and MS204. Information for all primers used in PCR and sequence reactions in this study are summarised in Table 2. The Mcm7 region was amplified with primers Mcm7-709 and Mcm7-1348 (Schmitt et al. 2009) and CAL with CAL2F and CAL2R2 primers (Duong et al. 2012). Some primers were modified at a few nucleotide sites to be more specific for species in Ceratocystis by aligning them to the C. fimbriata genome (GenBank accession number APWK01000000) (Wilken et al. 2014). For amplification of the FG1093 region, the FG1093F.cerato and FG1093R.cerato primers were modified from the original FG1093 E1F1 and FG1093 E3R1 primers (Walker et al. 2012b). For the MS204 region, the MS204F.cerato and MS204R.cerato primers were modified from the MS204 E1F1 and MS204 E5R1 primers. For species where problems were experienced in amplification, a smaller region of MS204 was amplified with the primers MS204F.ceratoB and MS204R.ceratoB. Various primer combinations were tested for the Tsr1 region. This included testing the original primers (Schmitt et al. 2009) and primers modified from the original (Tsr1.cerato), as well as a completely new forward primer designed in this region. Primers RPB2-5Fb and RPB2-7Rb, used to amplify the RPBII region, and primers T1d, Bt1d and Bt2d, used for amplification of the βT 2 region, were also designed from the C. fimbriata genome. For isolates where there were no reliable data available for the βT 1 and EF 1-α regions in GenBank, these were amplified using primers βt1a and βt1b (Glass and Donaldson 1995) for βT 1, and EF1-728F and EF1-986R (Jacobs et al. 2004) for EF 1-α.

The PCR reactions were identical to those performed by Duong et al. (2012), but 0.2 μM forward and reverse primer or 0.8 μM in the case of the degenerate primers were used per reaction. MgCl2 concentration differed for different primer sets (Table 2). The PCR program for amplification of the CAL, RPBII, βT 2, and MS204.ceratoB primer sets was identical to the program in previous studies (Duong et al. 2012). An Expand-PCR program was used for the ITS, Mcm7, βt 1, EF 1-α, MS204 (MS204.cerato) and FG1093 primer sets. The program was as follows: 96 °C 10 min, (94 °C 30 s, 55 °C 45 s, 72 °C 1 min) × 10 cycles, (94 °C 30 s, 55 °C 45 s, 72 °C 1 min +5 s/cycle increase) × 30 cycles, 72 °C 10 min. Annealing temperatures differed for each primer set (Table 2).

PCR and sequencing products were purified with 6 % Sephadex G-50 columns using the manufacturer’s protocols (Sigma–Aldrich, Germany). Amplification reactions for sequencing were performed, as described previously (Duong et al. 2012), using the ABI PRISM® BigDYE Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). All sequence data generated in this study were submitted to GenBank (see Table 1). For the FG1093 region, some isolates required cloning to obtain optimal sequencing results, and this was performed with a pGEM®-T Easy Vector System, following the manufacturer’s protocols (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

The quality of the raw sequence reads were evaluated and assembled in CLC Main Workbench v.6 (CLC bio, www.clcbio.com). Consensus sequences for each gene region of all isolates were aligned in MAFFT version 6, with the alignment strategy set to E-INS-i for the ITS data set and L-INS-i for all other data sets (Katoh et al. 2005). Alignment of the data sets was also manually inspected and edited in MEGA 5 (Tamura et al. 2011). Two of the gene regions contained a long poly-A repeat region, and this was excluded from the analyses. Maximum parsimony analysis (MP), maximum likelihood (ML), and Bayesian inference (BI) were applied to each data set individually for tree construction. Parsimony analysis was performed in PAUP* version 4.0 (Swofford 2002) and trees were obtained using the heuristic search option with 1,000 replicates, with random addition of sequences and a tree bisection and reconnection (TBR) branch swapping strategy. Both introns and exons were considered for each gene region. Indels were treated as a fifth character. For application in ML and BI analyses, the best model of evolution for each gene region was identified using the jModelTest version 0.1 and applying the Akaike information criterion (Posada 2008). ML tree construction was performed in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon and Gascuel 2003), with the following criteria: proportion of invariable sites was 0, gamma shape was estimated by the program, and the number of substitution sites was set to six (except for βT 1, where nst = 2). The starting tree was obtained using the BIONJ approach, and the branch swopping strategy was set to select the best of either NNI or SPR algorithms. Statistical support for the branches of both MP and ML trees was obtained using 1,000 replicates of non-parametric bootstrap analysis of the sequence data. As Ceratocystis pirilliformis resides in Ceratocystis but is distantly related to the species in the Latin American clade, it was selected as the outgroup to root the trees.

Additional branch support was obtained using Bayesian analysis, applying a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm in the MrBayes version 3.1.2 program (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). Tree searching was performed using four independent chains and run for 6 000 000 generations, sampling every 100th tree. Analyses were performed twice, and concordance between the two sets was investigated by comparing the log likelihoods in Tracer version 1.5 (Rambaut and Drummond 2009). The burn-in for each data set was performed in MrBayes and set to 10 000 generations. The posterior probabilities for the tree topology were obtained by constructing a consensus tree from the data using MrBayes and viewing it in TreeView X (Page 1996).

Phylogenetic value of single genes and gene combinations

A combination of criteria was used to select the gene regions with the most potential for use as phylogenetic markers. A three- and four-gene region combination was evaluated. This was based on i) the number of species that could be distinguished with significant bootstrap and Bayesian support values (>70 BS and >95 BI) by the gene region, ii) the number of species shown to be monophyletic based on the genealogical sorting index (gsi) value (Cummings et al. 2008), and iii) the congruence in tree topology as compared to a combined reference tree (Nye topological score) (Nye et al. 2006).

The gsiT is a statistical support value, in addition to BS and BI values, that indicates the exclusive ancestry of a group of organisms in a genealogy, and has proven informative in recent fungal phylogenetic studies (Sakalidis et al. 2011; Taole et al. 2012; Walker et al. 2012a). The analysis produces a value on a scale from 0 to 1 for each identified group, with 0 indicating no exclusive ancestry from other groups in the genealogy and 1 representing monophyly. For each gene region, the gsi value was calculated for 100 ML bootstrap trees randomly selected and 10 000 permutation tests were performed for statistical support of each gsi value. From these values, the gsiT was calculated as a weighted average of all 100 gsi values for each gene region, with a P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant (Sakalidis et al. 2011). All calculations were performed online at http://www.genealogicalsorting.org/index.php.

To determine the accuracy of each individual gene region in representing the relationships among all taxa, a Bayesian consensus tree for each gene region was compared to a combined reference tree of all of the gene regions (Aguileta et al. 2008). The combined reference tree was constructed from all eight gene regions using a Bayesian approach, as described in Aguileta et al. (2008), incorporating the corresponding nucleotide substitution model for each gene region. The topological difference in tree topologies were compared in the online program ‘Compare2Trees’ (http://www.mas.ncl.ac.uk/~ntmwn/compare2trees/index.html), based on an algorithm that compares the branches and partition of nodes between two trees and gives an overall topological congruence score (Nye et al. 2006). An overall score of 85 % was selected as the cutoff point for a marker to be compatible with the other regions considered.

The five most informative gene regions were selected on the basis of the three criteria as previously stated. A partition homogeneity test (PHT) with 1,000 repeats was performed on different arrangements of three- and four-gene region combinations in PAUP 4.0 to determine whether the sequences could be combined (Swofford 2002). The combined tree, based on three or four gene regions, was constructed using MP, ML and BI analyses. Identical conditions to those applied to the individual gene regions were used in the different tree construction methods.

Development of SNP markers

Sequence data generation for SNP calling

SNP markers were developed from 454 sequence data for six species in Ceratocystis. These markers could subsequently be used to consider variation in the rest of the species in this genus. This method was shown to be effective in a previous study on fungal species complexes (Pérez 2010; Pérez et al. 2012). To generate sequence data, reduced representations of genome sequences were generated with a protocol similar to the initial steps of an AFLP protocol up to the pre-amplification step (Myburg and Remington 2000) and sequenced with 454 pyrosequencing. Isolates included for sequencing were C. fimbriata (CMW 1547, 15049, 14799) (Table 1), C. cacaofunesta (CMW 14809, 15051, 14798), C. platani (CMW 14802, 23918, 23450), and a combined group comprising C. manginecans, C. acaciivora, C. mangicola, and C. mangivora (CMW 13851, 13852, 21123, 22563, 17568, 17570, 23623, 14797, 15052), which are referred to as the C. manginecans group in this part of the study.

All genomic DNA was digested with a frequent- and a rare-cutting restriction enzyme, after which restriction enzyme-specific adapters were ligated to the DNA fragments. A master mix digestion reaction consisting of 1× R/L buffer, 2 units EcoRI, 2 units MseI, and ddH2O to a final volume of 10 μl per sample was used to digest 150 ng genomic DNA. The DNA solution was made up to a 20 μl reaction volume with ddH2O, and this was mixed with 10 μl of master mix. The reaction was incubated for 3 hrs at 37 °C, and then 15 min at 65 °C. The ligation reaction was performed directly afterwards by combining 30 μl digested DNA with 10 μl ligation master mix (1× R/L buffer, 1 mM ATP pH7, 1 pmol EcoRI- and 10 pmol MseI adaptors, 1 unit T4 DNA ligase up to 40 μl final volume with ddH2O) and was incubated for 3 h at 22 °C.

Pre-amplification reactions were performed with 5 μl of the ligated products. Total reaction volumes of 30 μl consisted of 1× PCR buffer (+1.5 mM Mg), 0.2 mM dNTP, 0.3 μM EcoRI+A primer, 0.3 μM MseI+C primer, and 0.6 units Taq polymerase (Expand Taq). The PCR program was as follows: 94 °C for 4 min, (94 °C for 30 s; 56 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 1 min +1 s/cycle extra) × 25 cycles, 72 °C for 2 min. Amplification smears were analysed by AGE on a 2 % gel.

Amplicons of all the isolates of the same species were pooled in four sample sets representing C. fimbriata, C. cacaofunesta, C. platani, and C. manginecans. Amplicons were pooled by combining 25 μl PCR product of each isolate and then precipitated with 0.1 vol of 10 M NaOAc and 2.5 vol absolute ethanol and incubated on ice for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged and washed with 70 % ethanol and the dried product resuspended in 30 μl H2O. Sample sets were size-separated on a 1.2 % agarose gel at 60 V for 1 hr. Bands in the size range of 150–450 bp were excised and purified using the NucleoSpin® Extract II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany).

The 454 adapters with identity tags for each of the four species were added to the DNA fragments by means of a PCR reaction. The primer sequences for the forward reaction consisted of the 454 adaptor A sequence plus the species-specific sequence tag plus the EcoRI adaptor-specific sequence (sequence: 5’GCCTCCCTCGCGCCATCAG-NNNN-GACTGCGTACCAATTC3’). The reverse primer sequence consisted of the 454 adaptor B sequence, the species-specific sequence tag, and the MseI adaptor-specific sequence (sequence: 5’GCCTTGCCAGCCCGCTCAG–NNNN-GATGAGTCCTGAGTAA3’) (Pérez 2010). The species-specific identification tag was ATCG for the C. cacaofunesta sample set, CTAG for the C. fimbriata sample set, AGCT for the C. platani sample set, and CAGT for the C. manginecans samples. The program for the PCR amplification was 94° 2 min, (94 °C 30 s, 60 °C 30 s, 72 °C 60 s) × 25 cycles, and 72 °C for 2 min.

PCR amplicons from all four sample sets were precipitated using 10 μl NaOAc (10 M) and 200 μl absolute ethanol (100 %). DNA concentrations of all amplicons were adjusted to 30 ng/μl, and 20 μl of each of the four samples were pooled to a final volume of 80 μl. The product was sequenced using the Genome Sequencer 454 FLX (Roche, Inqaba Biotec, Pretoria, South Africa).

SNP identification, marker development and application to Ceratocystis species

Raw reads from the 454 sequencing were assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench 5.0 (CLC bio), and contigs were generated for orthologous regions containing sequences from all four species. Contigs were constructed with the following parameters: similarity = 0.8, length fraction = 0.5, insertion and deletion costs = 3, mismatch cost = 2 and minimum contig length = 200. Each contig was investigated individually to determine the presence of SNPs that were conserved within a species but able to differentiate between species. Informative contigs were identified based on the number of SNPs present in a contig (minimum of four SNPs) and the number of species between which the SNPs could differentiate. For the purposes of this study, a nucleotide difference was considered as a species-specific SNP only where it occurred in the majority of reads of at least one of the species. Regions that were present in the C. fimbriata genome more than once, based on BLAST results, and regions too variable for primer design were excluded.

For the selected contigs, primers were designed in the non-variable regions flanking the informative SNP region, using CLC Main Workbench 5.0 (CLC bio). Where SNPs were located inordinately close to the 3’ or 5’ end of the contig, the C. fimbriata genome (isolate CMW 14799, with GenBank accession number APWK01000000) was used to design primers located upstream or downstream from the SNP regions. Parameters were set for a maximum primer length of 22 bp, minimum primer length of 18 bp, maximum G/C content of 0.6, minimum G/C content of 0.4, maximum melting temperature of 58 °C and minimum melting temperature of 48 °C. All primer pairs were designed with Tm temperatures as close together as possible in order to simplify multiplex PCR reactions. The designed primers (Table S1) were synthesized by Inqaba Biotech (Pretoria, South Africa).

Each of the primer sets designed were first tested on the four species groups used for 454 sequencing. This was to ensure PCR success and to confirm the presence of the SNPs as predicted using the 454 data. The regions that were most informative and amplified well in the majority of species were selected and were amplified in three to five additional isolates of all other species included in this study (Table 1). PCR conditions were identical to those used for the single gene region amplification. The PCR program was as follow: 95° 5 min, (94 °C 30 s, 55 °C 30 s, 72 °C 90 s) × 38 cycles and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR products were amplified in 96-well PCR plates and purified using the ExoSAP method (Glenn and Schable 2005). Purified PCR products were used for amplification of sequencing products performed in 96-well MicroAmp® reaction plates. Sequencing products were purified using ethanol precipitation (Glenn and Schable 2005). The dried product was sequenced on an ABI PRISM® 3500xL auto-sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA).

Evaluation of SNP markers for species delimitation

Sequences from amplified SNP regions were assembled, analysed, and edited in the CLC Main Workbench 5.0 (CLC bio). Two different approaches were applied to investigate the SNP variation among the isolates. First, the entire sequenced region for each SNP primer set was considered and a combined data set of all SNP regions was generated. A cladogram was constructed from the data set based on MP and BI analyses, using settings similar to those used to analyse the single gene regions. Due to the presence of large indels, gaps were coded as a fifth character using FastGap version 1.0.7 (Borchsenius 2007). The best model of evolution for each SNP region was determined using the jModelTest 0.1 (Posada 2008) and was implemented in the BI analysis.

In the second approach, only the SNP sites (SNPs and indels) from each region were considered in constructing a haplotype network. All of the SNPs from the selected SNP regions were combined into a single concatenated SNP haplotype for each of the isolates. This was constructed by aligning the sequences of all isolates for each SNP region separately in MEGA 5 using MUSCLE alignment (Edgar 2004) and removing the constant sites. The variable sites from all SNP regions were then concatenated. Haplotypes were determined from the aligned SNP data in DnaSP v. 5 (Librado and Rozas 2009). Gaps were included for haplotype construction. The identified haplotypes were used as input data to construct a haplotype network, based on a median-joining algorithm on NETWORK v. 4.6.1.1 (Bandelt et al. 1999).

Results

Fungal isolates and DNA extraction

DNA extraction was successful for all of the 64 isolates considered and the concentrations ranged from 100 ng/μl to 1, 500 ng/μl. Analysis of the DNA quality, using AGE, indicated that the DNA was of acceptable quality with low levels of RNA contamination and the DNA for all the samples was diluted to a concentration of 30 ng/μl for PCR amplification reactions.

Single-copy phylogenetic gene regions

Primer design, PCR amplification and sequencing

PCR amplifications were successful for the majority of isolates for all gene regions other than Tsr1 and βT 2. Tsr1 had a very low PCR success level, and even though the βT 2 region amplified successfully, sequencing of this region was problematic due to a 12–16 nucleotide poly-A repeat in the intron region between exons 1 and 2. These gene regions were thus excluded from further analyses.

Amplification of the MS204 region with the MS204.cerato primer set (Table 2) resulted in poor sequence results for 13 of the isolates, but amplification with the redesigned primer set (MS204.ceratoB) produced high-quality sequences. The FG1093 region contained a 12 bp long poly-A repeat in some isolates, making downstream sequencing reactions challenging. Additionally, in isolates of C. colombiana and C. ecuadoriana, conflicting base calling was found at 10 nucleotide sites in the sequence chromatogram. For this reason, PCR products were cloned and both FG1093 haplotypes obtained for each species were included in the phylogenetic analyses. Sequence data for the ITS region of the majority of isolates was of good quality and did not contain any ambiguous sites. However, for 15 of the isolates, the data was unusable due to a long poly-A repeat in the gene region and GenBank data were used for these isolates in downstream analyses (Table 1). Reliable sequence data for the βT 1 and EF 1-α regions could also be obtained from GenBank for the majority of isolates (Table 1).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

Sequence alignment of the gene regions showed that, apart from ITS, the FG1093, MS204 and RPBII gene regions contained the greatest number of variable sites, while CAL and Mcm7 contained the least (Table S2). From the aligned sequence data of each gene region, the total number of characters that could be used for phylogenetic analysis and the number of parsimony informative characters were determined (Table 3). Even though RPBII had the greatest number of characters (1129 bp), ITS and EF 1-α had the most parsimony informative characters (197 and 42 bp, respectively).

The number of parsimonious trees produced from MP analysis, as well as the consistency index (CI) and retention index (RI) values obtained for each gene region, are summarised in Table 3. jModelTest suggested different evolutionary models for each gene region (Table 3), which were incorporated accordingly in ML and BI analyses. The log likelihood value for the most likely phylogenetic tree produced from ML analysis is summarised in Table 3. The tree topology for each region was congruent in all three methods of tree construction (MP, ML, and BI) and one of the most parsimonious trees was selected for representation for each gene region (Fig. S1). Maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood BS values and Bayesian PP values are indicated on the branches.

The ITS region was the only region that provided statistically significant support for all 15 Ceratocystis species investigated (Fig. S1a). This was supported by either >70 % bootstrap (BS) values from MP or ML analysis, or >95 % posterior probabilities (PP) produced by Bayesian analysis, or both. Phylogenetic trees produced from the regions Mcm7 (Fig. S1b) and EF 1-α (Fig. S1c) resulted in the lowest resolution, distinguishing only one (C. diversiconidia) and three (C. colombiana, C. cacaofunesta, and C. diversiconidia) species, respectively. The CAL gene region (Fig. S1d) provided support for four distinct species. FG1093, RPBII, βT 1 and MS204 phylogenetic trees could distinguish the greatest number of species. The FG1093 region enabled the recognition of five distinct species (Fig. S1e) and the RPBII region distinguished from four to seven species (Fig. S1f). High Bayesian PP values were obtained for seven monophyletic groups in RPBII, but some BS values were only between 60 % and 70 %. The βT 1 region (Fig. S1g) provided support for between five and six distinct species and MS204 delineated eight species (Fig. S1h).

Six of the species, C. acaciivora, C. manginecans, C. mangicola, C. mangivora, C. curvata, and C. eucalypticola, were significantly distinguished only by the ITS gene region (Fig. S1a). Even though C. mangicola and C. mangivora could not be distinguished using the other gene regions, the two species were supported as a single clade, separate from all other Ceratocystis species with βT 1 (87/63 % BS and 95 % PP) and RPBII (70 % MP BS) (Fig. S1f and S1g). Similarly, although not supported by other gene regions, C. curvata and C. eucalypticola were supported with values above 60 % in the EF 1-α, FG1093 and MS204 gene genealogies (Fig. S1c, 1e, and 1h).

The C. cacaofunesta isolates included in this study grouped in two distinct clades in the phylogenetic trees of six of the gene regions. The βT 1, CAL, MS204, EF 1-α, RPBII and ITS gene genealogies consistently grouped the isolates CMW 14803, 14809 and 15051 in one clade (Clade A) and CMW 14798 and 26375 in another clade (Clade B). The βT 1, CAL, MS204 and EF 1-α regions only provided significant branch support for Clade A to be distinct, RPBII only supported Clade B, and ITS significantly supported both clades. These isolates appear to represent distinct taxa.

Phylogenetic value of single genes and gene combinations

The gsiT values generally showed monophyly for the same species that had high phylogenetic branch support values, but could additionally suggest the degree of monophyly for the species that had low branch support values. The gsiT values for all species and all eight gene regions are summarised in Table 4. The gsi analysis provided significantly higher support values for at least two species in every gene region compared to the branch support values obtained by traditional phylogenetic analysis (highlighted in Table 4).

The species C. acaciivora had low but statistically significant gsiT values from the βT 1 (gsiT = 0.27) and ITS (gsiT = 0.47) gene regions. This indicated incomplete lineage sorting. Ceratocystis curvata and C. ecuadoriana had low branch support values in traditional phylogenetic analyses. The gsiT values were also low for C. curvata in the FG1093 and MS204 gene regions, with values of 0.37 and 0.4, but higher in EF 1-α, with gsiT = 0.7 (Table 4). For C. eucalypticola, the gsiT value in EF 1-α was not statistically significant, but FG1093 and MS204 indicated significantly higher values of 0.71 and 0.87, respectively. The separation of the C. cacaofunesta isolates into two clades was supported by five gene regions (ITS, CAL, βT 1, MS204 and Mcm7) for Clade A, with gsiT values ranging from 0.753 to 0.976; and RPBII supported Clade B, with a value of 0.923.

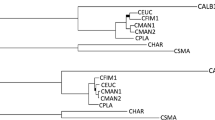

Comparison of tree topologies based on Nye topological score showed a minor level of conflict among all regions, as compared to the eight gene region combined tree (Fig. 1). Conflict was considered significant only where the specific branch was supported by >70 % MP or ML bootstrap support or >95 % Bayesian PP. The EF 1-α region showed the most conflict (80.4 %), while CAL had the highest level of congruence (96.8 %), followed by RPBII (94.4 %) and βT 1 (91 %) (Fig. 1).

Summary of the phylogenetic utility of all phylogenetic gene regions investigated in this study. The x-axis represents the different gene regions and the y-axis represents the number of species distinguished from a total of 15 distinct species defined in literature. The four columns for every gene region represent four alternative methods applied to the sequence data generated for species delineation. MP refers to maximum parsimony analysis with bootstrap support >70 %, ML to maximum likelihood, BI to Bayesian inference with posterior probabilities > 95 and gsi refers to the genealogical sorting index, with high values supporting the monophyly of a species. Underlined values above the bars of each gene region indicate how well the tree topology correlates with that of the combined tree constructed from all eight gene regions (Nei topological score).

The most significant conflict in the EF 1-α genealogy was the grouping of C. ecuadoriana and C. cacaofunesta as closest relatives (Fig. S1c). FG1093 showed conflict in the tree topology for two specific clades, indicating C. ecuadoriana and C. colombiana rather than C. ecuadoriana and C. neglecta to be closely related, and also grouped C. curvata in this clade (Fig. S1e). The positions of the second haplotypes of C. ecuadoriana and C. colombiana obtained from the cloned sequences were located more accurately when compared to the tree topologies of other gene regions. The second haplotype in C. ecuadoriana grouped with C. neglecta. The second C. colombiana haplotype was also supported as a distinct species. For this reason, the cloned sequences were used for the combined gene region analyses. Mcm7 analyses showed that both C. cacaofunesta clades were most closely related to C. colombiana and C. platani (Fig. S1b). MS204 grouped C. platani together in a clade with C. ecuadoriana and C. neglecta (Fig. S1h). RPBII grouped Clade B of C. cacaofunesta and C. colombiana together, but the internal node was not significantly supported (Fig. S1f).

The five gene regions that had the greatest potential to be applied as additional phylogenetic markers for delimitation of Ceratocystis species were identified based on the three criteria previously mentioned (Fig. 1). The RPBII, βT 1 and MS204 gene regions were identified as the three most informative gene regions for use in combination, with CAL and FG1093 as additional gene regions. Various combinations of the five gene regions were considered in order to identify the least number of genes required to distinguish all described species in Ceratocystis. The partition homogeneity test (PHT) performed on the gene combinations produced values as follow: 0.063 for the RPBII, βT 1 and MS204 gene combination; a value of 0.099 for the four-gene combination where CAL was included; and 0.01 for the four-gene combination where FG1093 was included. Even though the last value is low, it is still acceptable, and the gene combination would not decrease the phylogenetic accuracy (Cunningham 1997).

The three-gene combination including RPBII, βT 1, and MS204 provided effective delineation among most species in Ceratocystis. However, they could not be used to distinguish C. eucalypticola, C. curvata, C. acaciivora, C. manginecans, C. mangicola or C. mangivora from each other. The four-gene combination of RPBII, βT 1, and MS204, and including CAL, did not add any significance to the phylogenetic tree, and CAL was excluded from further analyses. Including the FG1093 region in the four-gene combination increased the statistical values to support C. eucalypticola and C. curvata as distinct species. In order to illustrate the resolution obtained from the four most informative gene regions, this combination was selected to construct the tree for presentation (Fig. 2). The results obtained for the phylogenetic analyses using this gene combination are summarised in Table 3.

One of the most parsimonious trees selected from maximum parsimony analysis for representation of the Ceratocystis species phylogeny. This was constructed from the combined data from the gene regions βT 1, FG1093, MS204, and RPBII. The ex-type strain of each species is indicated by T. Branch support values are indicated above the branches, and include bootstrap values above 60 from MP/ML analysis. Bayesian posterior probability above 95 % is indicated by thick branches. An * indicates support values from any of the analyses below the threshold.

Development of SNP markers

Sequence data generation for SNP calling

The 454 pyrosequencing produced 33 418 reads, with an average read length of 200 bases. The number of reads per species group ranged from 3000 (C. manginecans) to 13 000 (C. platani) and could be assembled into 867 contigs. About 65 contigs were discarded either because they consisted of a single read or because the contigs showed no variation among species. The contigs that were retained for further use had a coverage ranging from 3 to 270 reads per contig.

SNP identification, marker development and application to Ceratocystis species

A total of 29 primer pairs were designed (Table S1), with an annealing temperature of 55 °C. The majority of the primer sets resulted in successful amplification in all 62 isolates, producing a single band with expected fragment sizes for the different primer sets (Table S1). SNP region 8 could not be amplified in C. diversiconidia, and SNP region 12 could not be amplified in C. mangivora, despite several attempts at optimisation. These two regions were represented by "N" for subsequent analyses. Sequencing was successful for the majority of samples after the first attempt, but some required optimisation by increasing the annealing temperature to 57–58 °C in the amplification reaction for sequencing. Amplification and sequencing for SNP regions 1, 2, 14, and 29 could not be optimized and were excluded from subsequent analyses.

Evaluation of SNP markers for species delimitation

The nine most informative SNP regions identified were SNP 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 24, 26 and 32, and the sequence data for these gene regions were submitted to GenBank (Table S3). The full-length sequence data of all nine combined SNP regions resulted in 2,518 characters after alignment, which were used for cladogram construction. A total of 23 indels were present in the alignment, and these were coded and included in analyses, resulting in a total of 354 parsimony informative characters. The SNPs thus provided a greater number of informative characters than the 305 sites obtained from the seven single-copy genes (Table S2 and S3). Since the nine most informative SNP regions were amplified and sequenced in all Ceratocystis species investigated, additional SNPs not initially detected in the 454 sequence data were identified.

Maximum parsimony analysis showed a CI of 0.770 and an RI of 0.960, and four most parsimonious trees were produced from the analysis. jModelTest indicated the HKY evolutionary model for SNP8 and SNP18, TIM1+G for SNP10, TrN+G for SNP12, TPM2uf+I for SNP15, TIM1+I for SNP16, TIM1+I+G for SNP24, TPM3uf+G for SNP32, and HKY+I for SNP26. The MP and BI approaches resulted in the same tree topology, and both had a high level of branch support for each clade. One of the cladograms based on MP analysis was selected for presentation (Fig. 3a) and support values are shown above the branches. Strongly supported distinct groupings could be seen in the cladogram for C. colombiana, C. curvata, C. diversiconidia, C. ecuadoriana, C. eucalypticola, C. fimbriata, C. fimbriatomima, C. mangicola, C. mangivora, C. manginecans, C. neglecta, C. papillata, and C. platani. As was true for the protein-coding genes, C. cacaofunesta isolates resided in two different clades. Most C. acaciivora isolates could not be distinguished from C. manginecans, but isolates CMW 22563 and 22562 were located farther away from the others, since they had nucleotide differences in two SNP regions at three SNP sites (Table S3).

Species delineation of Ceratocystis species based on SNP variation from the nine amplified SNP regions. a) Cladogram of Ceratocystis isolates based on all amplified SNP regions considering the sequence of the entire SNP region. The ex-type strain of each species is indicated by T. Maximum parsimony analysis and Bayesian inference were performed on all represented isolates. Bootstrap support values are indicated at each branch and Bayesian posterior probability values >95 are indicated by thick branches. b) Haplotype network constructed based on a median-joining algorithm. Only the SNP sites obtained from nine SNP regions were considered. Nodes (circles) represent haplotypes and the size of the node corresponds to the number of isolates included in the haplotype. Coloured nodes represent existing individuals, coloured according to their species status as suggested by ITS sequence data. Black internal nodes represent missing haplotypes.

Analyses based only on the SNP sites resulted in a total of 360 characters comprising 181 SNPs and 23 indels (Table S3). The SNP data provided fixed SNP differences among all of the species with the exception of some of the C. acaciivora isolates that were identical to C. manginecans. A total of 29 haplotypes were revealed in the SNP data. However, the network analysis combined some of the haplotypes at a single node, resulting in 25 external nodes (Fig. 3b). Most isolates of a single species showed minor levels of variation, whereas a higher level of variation was clear within the C. platani isolates. The isolates from the U.S. represented two separate haplotypes, and the isolates from Europe (Greece and Switzerland) represented a third haplotype. Despite the slight variation observed within a species, 13 of the species defined using ITS sequence data were clearly separated in the network, and the relatedness among species correlated with what was seen in the cladogram.

Taxonomy

Ceratocystis acaciivora, identified from Acacia trees in Indonesia (Tarigan et al. 2011), was shown to be indistinguishable from C. manginecans based on phylogenetic sequence data and SNP marker data generated in this study. Isolates of both species had identical DNA sequences in the βT 1, MS204, RPBII, Mcm7, CAL and FG1093 gene regions. The two species also could not be distinguished based on the SNP markers designed in this study. Ceratocystis acaciivora was primarily distinguished from C. manginecans based on ITS sequence data (Tarigan et al. 2011), but the occurrence of both ITS types in a single isolate (Al Adawi et al. 2013; Naidoo et al. 2013) makes this region an unreliable phylogenetic marker for the two species. Based on this result, C. acaciivora is reduced to synonymy with C. manginecans, as follows:

-

Ceratocystis manginecans M. van Wyk, A.O. Al Adawi & M.J. Wingf., Fungal Diversity 27(1): 224 (2007)

-

= Ceratocystis acaciivora M. Tarigan & M. van Wyk, S. Afr. J. Bot. 77(2):301 (2011)

Discussion

The delimitation of many species in Ceratocystis has been strongly reliant on sequence data from the ITS region. In this study, seven gene regions and nine SNP markers were used to reconsider the boundaries of 15 of these taxa described in the Latin American clade of the genus. The resolution of these markers was compared with that provided by the ITS, βT 1 and EF 1-α gene regions (Mbenoun et al. 2013; Tarigan et al. 2011; Van Wyk et al. 2011b). While none of these alternative regions were able to support all of the species defined by ITS phylogenies, a combination of four gene regions (βT 1, RPBII, MS204 and FG1093) provided significant support for the delineation of most species. The SNP markers developed were more informative than the gene regions, making it possible to clearly distinguish among all but two species, and also revealed the presence of at least one new cryptic species.

Of the seven gene regions evaluated in this study, RPBII and MS204 distinguished the greatest number of species in Ceratocystis. These two gene regions were as informative as the βT 1 region and were significantly more useful than EF 1-α (Fig. 1). A combination of RPBII, MS204 and βT 1 provided the best resolution, and supported the delineation of 11 of the 15 species in Ceratocystis. Even though the FG1093 region was not as informative as the aforementioned regions, it provided support for differentiation of one additional species, C. curvata, not distinguished by the combined three-gene phylogeny (Fig. S1). The apparent existence of two copies of the FG1093 region in some species requires careful consideration of the sequence quality obtained from amplicons before it is used in analyses.

Four of the gene regions, CAL, βT 2, Mcm7, and Tsr1, considered in this study were not useful for species delineation. Even though the tree topology for the CAL gene region was highly congruent with that of other gene regions (Fig. 1), it did not increase the phylogenetic resolution in the combined species tree. The Tsr1 gene region had a low PCR success rate and the Mcm7 region provided negligible phylogenetic resolution. Such technical difficulties in the use of these gene regions have been previously reported (Raja et al. 2011; Schmitt et al. 2009; Tretter et al. 2013). The βT 2 region should also be avoided in phylogenetic studies in Ceratocystis, as it is difficult to obtain sequences for this gene region.

The SNP markers developed in this study provide a powerful diagnostic tool to distinguish between species in Ceratocystis. The markers provided support for 13 distinct species and are thus more informative than the protein-coding genes investigated. The SNPs provided support for C. mangicola and C. mangivora as distinct species and provided a higher level of support for the monophyly of C. curvata and C. eucalypticola than the protein-coding gene regions. The fact that all isolates for a specific species contained fixed SNPs, and consistently grouped together in the network and cladogram constructed, raises confidence in the SNP regions.

The collective data derived from the evaluated gene regions and SNP markers provided new insights into the boundaries of three species in Ceratocystis. The C. cacaofunesta isolates were differentiated into two separate groups, with significant branch support values (Fig. S1) obtained from six of the gene regions (Table S2) as well as the combined SNP markers (Fig. 3). ITS sequence data and mating studies initially used to identify this species (Engelbrecht and Harrington 2005; Ferreira et al. 2010) suggested that there were two distinct lineages (Ecuador and Brazil/Costa Rica) for South American isolates of Ceratocystis from cacao. Results from this study and all other currently available data strongly suggest that the isolates CMW 14803, 14809 and 15051 of C. cacaofunesta represent an undescribed species in Ceratocystis. Ceratocystis acaciivora and C. manginecans could not be distinguished using any of the seven markers considered in this study. These species can only be distinguished using the ITS region, which has clearly emerged as unusable since two ITS types can occur in a single isolate (Harrington et al. 2014; Naidoo et al. 2013), such as in C. manginecans (Al Adawi et al. 2013). These data provided justification to reduce C. acaciivora to synonymy with C. manginecans in this study.

Results of this study have shown that most species described in Ceratocystis can be distinguished based on the combined sequence data of the βT 1, RPBII, MS204 and FG1093 gene regions. This is supported by the suite of SNP markers, which provided data congruent with the gene region phylogenies. If alternative approaches to the GCPSR are used to define species in Ceratocystis, fewer species might be resolved. This has been observed, for example, when only a single gene region, the MAT gene, and intersterility tests between individual isolates in Ceratocystis were investigated (Harrington et al. 2014). There is a strong case to support the species boundaries presented in this study and accepting these will provide opportunities to better understand the biology and ecology of an important group of fungi.

References

Aguileta G, Marthey S, Chiapello H, Lebrun MH, Rodolphe F, Fournier E, Gendrault-Jacquemard A, Giraud T (2008) Assessing the performance of single-copy genes for recovering robust phylogenies. Syst Biol 57:613–627. doi:10.1080/10635150802306527

Al Adawi AO, Barnes I, Khan IA, Al Subhi AM, Al Jahwari AA, Deadman ML, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2013) Ceratocystis manginecans associated with a serious wilt disease of two native legume trees in Oman and Pakistan. Australas Plant Pathol 42:179–193

Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A (1999) Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16:37–48

Barnes I, Roux J, Wingfield BD, Dudzinski MJ, Old KM, Wingfield MJ (2003) Ceratocystis pirilliformis, a new species from Eucalyptus nitens in Australia. Mycologia 95:865–871

Borchsenius F (2007) FastGap 1.0.7. Software distributed by the author (http://192.38.46.42/aubot/fb/FastGap_home.htm)

Bridge PD, Spooner BM, Roberts PJ (2005) The impact of molecular data in fungal systematics. In: Callow JA (ed) Advances in botanical research, vol 42. Academic Press, pp 33–67

Cai L, Giraud T, Zhang N, Begerow D, Cai G, Shivas R (2011) The evolution of species concepts and species recognition criteria in plant pathogenic fungi. Fungal Divers 50:121–133. doi:10.1007/s13225-011-0127-8

Chouvarine P, Cooksey AM, McCarthy FM, Ray DA, Baldwin BS, Burgess SC, Peterson DG (2012) Transcriptome-based differentiation of closely-related Miscanthus lines. PLoS One 7:e29850. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029850

Cummings MP, Neel MC, Shaw KL (2008) A genealogical approach to quantifying lineage divergence. Evolution 62:2411–2422. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00442.x

Cunningham CW (1997) Can three incongruence tests predict when data should be combined? Mol Biol Evol 14:733–740

De Beer ZW, Duong TA, Barnes I, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2014) Redefining Ceratocystis and allied genera. Stud Mycol 79:187–219. doi:10.1016/j.simyco.2014.10.001

Duong TA, De Beer ZW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2012) Phylogeny and taxonomy of species in the Grosmannia serpens complex. Mycologia 104:715–732. doi:10.3852/11-109

Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh340

Engelbrecht CJB, Harrington TC (2005) Intersterility, morphology and taxonomy of Ceratocystis fimbriata on sweet potato, cacao and sycamore. Mycologia 97:57–69. doi:10.3852/mycologia.97.1.57

Fakhrai-Rad H, Pourmand N, Ronaghi M (2002) Pyrosequencing™: An accurate detection platform for single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Mutat 19:479–485. doi:10.1002/humu.10078

Ferreira EM, Harrington TC, Thorpe DJ, Alfenas AC (2010) Genetic diversity and interfertility among highly differentiated populations of Ceratocystis fimbriata in Brazil. Plant Pathol 59:721–735

Garvin MR, Marcotte RW, Palof KJ, Riley RJ, Kamin LM, Gharrett AJ (2011) Diagnostic single-nucleotide polymorphisms identify Pacific ocean perch and delineate blackspotted and rougheye rockfish. Trans Am Fish Soc 140:984–988. doi:10.1080/00028487.2011.603984

Giraud T, Refrégier G, Le Gac M, De Vienne DM, Hood ME (2008) Speciation in fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 45:791–802. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2008.02.001

Glass NL, Donaldson GC (1995) Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1323–1330

Glenn TC, Schable NA (2005) Isolating microsatellite DNA loci. In: Zimmer EA, Roalson EH (eds) Methods in Enzymology, vol 395. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 202–222

Goodwin SB, Drenth A, Fry WE (1992) Cloning and genetic analysis of two highly polymorphic, moderately repetitive nuclear DNAs from Phytophthora infestans. Curr Genet 22:107–115

Guindon S, Gascuel O (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52:696–704

Halsted BD (1890) Some fungous disease of the sweet potato. Agric Coll Exp Station Bull 76:1–32

Halsted BD, Fairchild DG (1891) Sweet-potato black rot. J Mycol 7:1–11

Harrington TC (2000) Host specialization and speciation in the American wilt pathogen Ceratocystis fimbriata. Fitopatol Bras 25S:262–263

Harrington TC, Kazmi MR, Al-Sadi AM, Ismail SI (2014) Intraspecific and intragenomic variability of ITS rDNA sequences reveals taxonomic problems in Ceratocystis fimbriata sensu stricto. Mycologia 106:224–242. doi:10.3852/13-189

Jacobs K, Bergdahl DR, Wingfield MJ, Halik S, Seifert KA, Bright DE, Wingfield BD (2004) Leptographium wingfieldii introduced into North America and found associated with exotic Tomicus piniperda and native bark beetles. Mycol Res 108:411–418. doi:10.1017/S0953756204009748

Jones JC, Fan S, Franchini P, Schartl M, Meyer A (2013) The evolutionary history of Xiphophorus fish and their sexually selected sword: a genome-wide approach using restriction site-associated DNA sequencing. Mol Ecol 22:2986–3001. doi:10.1111/mec.12269

Kamgan NG, Wingfield MJ, Mohammed C, Carnegie AJ, Pegg GS, Roux J (2012) Ceratocystis species, including two new species associated with nitidulid beetles, on eucalypts in Australia. Anton Leeuw 101:217–241

Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T (2005) MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res 33:511–518

Kile GA, Harrington TC, Yuan ZQ, Dudzinski MJ, Old KM (1996) Ceratocystis eucalypti sp. nov., a vascular stain fungus from eucalypts in Australia. Mycol Res 100:571–579. doi:10.1016/s0953-7562(96)80010-4

Librado P, Rozas J (2009) DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25:1451–1452

Lindner DL, Banik MT (2011) Intragenomic variation in the ITS rDNA region obscures phylogenetic relationships and inflates estimates of operational taxonomic units in genus Laetiporus. Mycologia 103:731–740. doi:10.3852/10-331

Marthey S, Aguileta G, Rodolphe F, Gendrault A, Giraud T, Fournier E, Lopez-Villavicencio M, Gautier A, Lebrun M-H, Chiapello H (2008) FUNYBASE: a FUNgal phYlogenomic dataBASE. BMC Bioinformatics 9:456. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-456

Mbenoun M, Wingfield MJ, Begoude Boyogueno A, Wingfield BD, Roux J (2013) Molecular phylogenetic analyses reveal three new Ceratocystis species and provide evidence for geographic differentiation of the genus in Africa. Mycol Prog 13:219–240. doi:10.1007/s11557-013-0907-5

Myburg AA, Remington DL (2000) Protocol for high-throughput AFLP analysis using LI-COR IR2 automated sequencer. North Carolina State Forest Biotechnology AFLP protocol N C State Univ For Dep, Raleigh

Naidoo K, Steenkamp ET, Coetzee MPA, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD (2013) Concerted evolution in the ribosomal RNA cistron. PLoS One 8:e59355. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059355

Nye TMW, Liò P, Gilks WR (2006) A novel algorithm and web-based tool for comparing two alternative phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 22:117–119. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti720

O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E (1997) Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol Phylogenet Evol 7:103–116. doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0376

O’Donnell K, Nirenberg H, Aoki T, Cigelnik E (2000) A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: Detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 41:61–78. doi:10.1007/bf02464387

Page RDM (1996) TREEVIEW: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci 12:357–358

Pavlic D (2009) Taxonomy and population diversity of Botryosphaeriaceae associated with woody hosts in South Africa and Western Australia. University of Pretoria, Pretoria

Pérez G (2010) Chapter 6: inter-specific SNPs for cryptic species delimitation and phylogenetic reconstructions in closely related species. In: Global genetic diversity of the Eucalyptus leaf pathogen Teratosphaeria nubilosa species complex in native forests and commercial plantations. Microbiology and Plant Pathology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria pp 185–205

Pérez G, Slippers B, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD, Carnegie AJ, Burgess TI (2012) Cryptic species, native populations and biological invasions by a eucalypt forest pathogen. Mol Ecol 21:4452–4471. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05714.x

Posada D (2008) jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol 25:1253–1256

Raja AH, Schoch CL, Hustad VP, Shearer CA, Miller AN (2011) Testing the phylogenetic utility of Mcm7 in the Ascomycota. MycoKeys 1:63–94

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ (2009) Tracer v1.5. Institute of evolutionary biology

Rintoul TL, Eggertson QA, Lévesque CA (2012) Multigene phylogenetic analyses to delimit new species in fungal plant pathogens. In: Bolton MD, Thomma BPHJ (eds) Plant fungal pathogens: methods and protocols, vol 835. Methods in molecular biology. Humana Press, pp 549–569

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–1574

Roux J, Van Wyk M, Hatting H, Wingfield MJ (2004) Ceratocystis species infecting stem wounds on Eucalyptus grandis in South Africa. Plant Pathol 53:414–421

Sakalidis ML, Hardy GESJ, Burgess TI (2011) Use of the Genealogical Sorting Index (GSI) to delineate species boundaries in the Neofusicoccum parvum–Neofusicoccum ribis species complex. Mol Phylogenet Evol 60:333–344. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.04.026

Schmitt I, Crespo A, Divakar PK, Fankhauser JD, Herman-Sackett E, Kalb K, Nelsen MP, Nelson NA, Rivas-Plata E, Shimp AD, Widhelm T, Lumbsch HT (2009) New primers for promising single-copy genes in fungal phylogenetics and systematics. Persoonia 23:35–40

Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA, Chen W (2012) Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:6241–6246

Seifert KA (2009) Progress towards DNA barcoding of fungi. Mol Ecol Resour 9:83–89. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02635.x

Spatafora JW (2005) Assembling the fungal tree of life (AFTOL). Mycol Res 109:755–756

Swofford DL (2002) PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods). 4 edn. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr121

Taole M, Burgess T, Gryzenhout M, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2012) DNA sequence incongruence and inconsistent morphology obscure species boundaries in the Teratosphaeria suttonii species complex. Mycoscience 53:270–283. doi:10.1007/s10267-011-0164-x

Tarigan M, Roux J, Van Wyk M, Tjahjono B, Wingfield MJ (2011) A new wilt and die-back disease of Acacia mangium associated with Ceratocystis manginecans and C. acaciivora sp. nov. in Indonesia. S Afr J Bot 77:292–304. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2010.08.006

Taylor JW, Jacobson DJ, Kroken S, Kasuga T, Geiser DM, Hibbett DS, Fisher MC (2000) Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 31:21–32. doi:10.1006/fgbi.2000.1228

Tretter ED, Johnson EM, Wang Y, Kandel P, White MM (2013) Examining new phylogenetic markers to uncover the evolutionary history of early-diverging fungi: comparing MCM7, TSR1 and rRNA genes for single- and multi-gene analyses of the Kickxellomycotina. Persoonia 30:106–125

Upadhyay HP (1981) A monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis. University of Georgia Press, Athens

Van Wyk M, Wingfield BD, Marin M, Wingfield MJ (2010) New Ceratocystis species infecting coffee, cacao, citrus and native trees in Colombia. Fungal Divers 40:103–117. doi:10.1007/s13225-009-0005-9

Van Wyk M, Wingfield BD, Al-Adawi AO, Rossetto CJ, Ito MF, Wingfield MJ (2011a) Two new Ceratocystis species associated with mango disease in Brazil. Mycotaxon 117:381–404

Van Wyk M, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2011b) Four new Ceratocystis spp. associated with wounds on Eucalyptus, Schizolobium and Terminalia trees in Ecuador. Fungal Divers 46:111–131

Van Wyk M, Roux J, Kamgan NG, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2012) Ceratocystis eucalypticola sp. nov. from Eucalyptus in South Africa and comparison to global isolates from this tree. IMA Fungus 3:45–58

Walker DM, Castlebury L, Rossman A, Mejía L, White J (2012a) Phylogeny and taxonomy of Ophiognomonia (Gnomoniaceae; Diaporthales), including twenty-five new species in this highly diverse genus. Fungal Divers 57:85–147. doi:10.1007/s13225-012-0200-y

Walker DM, Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, White JF (2012b) New molecular markers for fungal phylogenetics: Two genes for species-level systematics in the Sordariomycetes (Ascomycota). Mol Phylogenet Evol 64:500–512

Wang XQ, Zhao L, Eaton DAR, Li DZ, Guo ZH (2013) Identification of SNP markers for inferring phylogeny in temperate bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) using RAD sequencing. Mol Ecol Resour 13:938–945. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.12136

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) PCR Protocols: A sequencing guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 315–322

Wilken PM, Steenkamp ET, Wingfield MJ, De Beer ZW, Wingfield BD (2014) Draft nuclear genome sequence for the plant pathogen, Ceratocystis fimbriata. IMA Fungus 4:357–358. doi:10.5598/imafungus.2013.04.02.14

Wingfield MJ, De Beer C, Visser C, Wingfield BD (1996) A new Ceratocystis species defined using morphological and ribosomal DNA sequence comparisons. Syst Appl Microbiol 19:191–202

Wingfield BD, Van Wyk M, Roos H, Wingfield MJ (2013) Ceratocystis: Emerging evidence for discrete generic boundries. In: Seifert KA, De Beer W, Wingfield MJ (eds) Ophiostomatoid Fungi: Expanding Frontiers. CBS Biodiversity series, vol 12. CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, AD Utrecht, The Netherlands, pp 57–64

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Tree Protection Co-operative Programme (TPCP), the National Research Foundation (NRF) as well as the Genomics Research Institute (GRI) at the University of Pretoria for the financial support they provided for this research. We also acknowledge the Thuthuka Foundation (grant no 80670) for the provision of a student bursary grant to Arista Fourie. Lastly, we want to thank Dr. Wilhelm de Beer and Dr. Tuan Duong, from the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), for their assistance with some of the primers designed for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fourie, A., Wingfield, M.J., Wingfield, B.D. et al. Molecular markers delimit cryptic species in Ceratocystis sensu stricto . Mycol Progress 14, 1020 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-014-1020-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-014-1020-0