Abstract

We reviewed research that examines racism as an independent variable and one or more health outcomes as dependent variables in Black American adults aged 50 years and older in the USA. Of the 43 studies we reviewed, most measured perceived interpersonal racism, perceived institutional racism, or residential segregation. The only two measures of structural racism were birth and residence in a “Jim Crow state.” Fourteen studies found associations between racism and mental health outcomes, five with cardiovascular outcomes, seven with cognition, two with physical function, two with telomere length, and five with general health/other health outcomes. Ten studies found no significant associations in older Black adults. All but six of the studies were cross-sectional. Research to understand the extent of structural and multilevel racism as a social determinant of health and the impact on older adults specifically is needed. Improved measurement tools could help address this gap in science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Older Black Americans experience earlier mortality and higher rates of many chronic conditions compared to their White counterparts. [1] Since race is a social construct (or, as Dr. Camara Jones defines, a “social interpretation of how one looks”), it is inherently not a risk factor for disease. Race is instead a risk factor for racism which is associated with negative health outcomes. [2,3,4] A Black American aged 65 years today lived the first decade of their life during legally enforced racial segregation during the Jim Crow Era. The current generation of older Black Americans experienced both legalized discrimination prior to 1965, as well as less blatant but dangerously persistent systems of racism that continues to impact Americans of Color today. [5] Understanding and addressing the influence of racism on health is crucial to targeting health disparities in older adults, as well as in reducing overall morbidity and mortality from chronic health conditions in this country.

Racism can be classified into three different levels of operation: interpersonal, institutional, and structural. Interpersonal racism affects health at the individual level through encountering discrimination based on race in everyday social interactions. [6] This individual level of racism includes microaggressions and unfair treatment that can be harmful regardless of whether there were malicious intentions. Institutional racism affects health when agencies or organizations in a particular sector discriminate against people based on their race. [5] If a company underpays employees of Color, or if hospitals provide different qualities of care to patients based on their race, institutional racism invariably widens disparities. Similarly, this occurs even if inequitable policies and subsequent practices are neither intentional nor obvious. Finally, structural racism is enacted through discrimination that occurs across institutions, systems, and contexts through coinciding racist policies and practices that do not depend on the decisions of just one individual, organization, or sector. [5] These overlapping policies and practices preferentially offer opportunities, advantages, services, or supports to one racial group while depriving other racial groups of those same benefits. [5, 7] For example, a person could accumulate exposure to structural racism due to the systematic denial of home loans combined with the disproportionate incarceration rates experienced by Black Americans. [8, 9] Americans of Color are impacted by the coinciding effects of racism inflicted at the interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels. [5, 6]

Racism is a fundamental cause of health disparities in the USA, but the specifics of how and to what extent racism affects health outcomes are not well-established. Racism affects every age group of every minoritized racial and ethnic group in the USA. It is important to study racism and health in older Black Americans because of the uniquely harmful effects that the Jim Crow Era had in this group throughout history and because of the magnitude of health disparities between older Black and older White Americans. Additionally, a focus on older adults allows for improved understanding of cumulative disadvantage over the life course – or the increasing effects of inequality on health over time. [10]

Researchers have conducted systematic reviews specific to racism or discrimination and health. [11,12,13,14,15,16] Previous reviews have examined the relationship between racism or discrimination and one type of health outcome such as hypertension, [13, 17] allostatic load, [18] or mental health. [12, 14] Other reviews focused on a specific level of racism, such as perceived interpersonal racism. [11] To our knowledge, no reviews have examined the relationship between all levels of racism and all health outcomes in older Black Americans. In this study, we aim to systematically review research examining the relationship between racism at the interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels and any health outcome in older Black Americans. Our objective is to provide a comprehensive assessment of the strengths and gaps of the current body of scholarly literature on the health impacts of racism in older Black Americans to inform future research on this important and understudied contributor to health disparities.

Methods

Search Strategy

With the support of an informationist, we searched five databases in January 2021: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Racism-related search terms included discriminat*, prejudic*, bias, segregat*, and racis*. Aging-related search terms included: aged, older, elder*, senior, and geriatric*. To capture studies that included Black participants, we used the terms Black, Blacks, and African American. We used the truncation operator (*) to capture all words that contain a particular root (e.g., discriminat* for discriminate, discrimination, discriminated, discriminating, discriminatory, discriminates) in databases that allow. In databases that did not allow, we wrote out the multiple words sharing a trunk as separate search terms.

Selection Criteria

We included articles describing peer-reviewed, empirical, quantitative studies based in the USA that used a measure of racism as an independent variable and a health outcome as a dependent variable, included only participants over the age of 50 years or specifically reported results for participants over the age of 50, and included only Black participants or specifically reported results for Black participants. We selected 50 years as the age cutoff in this study as opposed to a later one out of consideration that in 2018, non-Hispanic Black male populations still presented with the lowest life expectancy at birth (71.3 years as compared to non-Hispanic White males, 76.2 years; non-Hispanic Black females, 78.0 years; and non-Hispanic White females, 81.1 years) [19]. We excluded studies published more than 10 years ago due to the clarification of concepts over the past decade, such as the levels of racism. [5] We included studies that identified “racial composition” or a related term as an independent variable if the paper identified “racism” or “discrimination” as a concept of interest in the abstract, introduction, and/or methods of the manuscript.

Study Identification

We identified 11,256 articles for screening and imported them into Covidence software for review. [20] After removing 3349 duplicates, 7907 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Two study team members (SEL and QS) each reviewed all study titles and abstracts to remove irrelevant studies. A third study team member was available to resolve conflicts but was not requested to do so since both study team members came to consensus through discussions and rereviewing abstracts. During the title and abstract screening, we removed 7535 references due to irrelevance. A total of 372 studies remained for full-text screening which one study team member (SEL) completed. Out of the total studies, we excluded an additional 329 manuscripts due to not providing results on the direct relationship between racism and one or more health outcomes among Black adults aged 50 or older (283), not being peer-reviewed (36), being further duplicates of included studies (9), and not studying participants in the USA (1). After removing these 329 studies, 43 studies remained for data extraction. [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] Two study team members (SEL and either JJS, AB, or MCF) independently completed data extraction for each included article and cross-checked all results to ensure the accuracy of extraction. See Fig. 1 for the PRISMA diagram.

Data Extraction

For each of the 43 included studies, we recorded characteristics including racial/ethnic groups included in sample, inclusion and exclusion criteria, parent study or dataset, measure(s) of racism and if validated, measure(s) of health, study design, sample size, and association(s) between racism and health. For a racism instrument to be considered validated, authors needed to provide validation statistics, provide a citation for a validity/reliability study of the instrument, or use an objective data source (e.g., statistics of racial composition in a census tract). If a study measured a health outcome as well as other dependent variables such as a measure of treatment type or patient experience, we only extracted the findings related to health outcomes. If a study included younger participants or non-Black participants, we only extracted the findings in Black participants aged 50 years or older.

We categorized health outcome measures as “cardiovascular,” “mental health,” “cognition,” “physical function,” “telomere length,” or “general health/other.” We categorized racism measures as “perceived interpersonal,” “perceived institutional,” “institutional indicator” (assessing exposure to a racist policy in one context, such as education, based on participant zip code) or “structural indicators.” We only classified measures of racism that assessed exposure to policies, practices, systems, or structures across two or more contexts (e.g., education and employment) as assessing at the structural level of racism. Although there is lack of consensus on the distinction between institutional and structural racism, leading scholars support this conceptualization of structural racism. [5, 63]

See Table 1 for a detailed summary of each included study and Table 2 for a quick reference of study characteristics and findings.

Results

Study Characteristics

Of the 43 included studies, 13 were published in health outcome-specific journals [25, 33, 35, 37, 38, 42, 44, 47, 51, 56, 58, 59, 62] (e.g., Breast Cancer Research and Treatment), 15 in aging-specific journals [21, 22, 24, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 45, 53,54,55, 57, 60, 61] (e.g., Journals of Gerontology), four in racial disparities or race-specific journal [23, 41, 49, 52] (e.g., Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities) and the remainder in general health and social science journals [26, 27, 29, 31, 39, 40, 43, 46, 48, 50, 64] (e.g., PLOS One).

Twenty-six of the studies included only Black participants, [21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 31,32,33,34, 37, 38, 40, 42, 44, 45, 49, 50, 53,54,55, 57,58,59,60,61,62] 18 included Black and White participants only, [22, 25, 26, 29, 30, 35, 36, 39, 41, 43, 46,47,48, 51, 52, 56, 61, 64] and seven included Black, White, and Hispanic (of any race) participants. [22, 29, 30, 36, 46, 52, 61] None of the eligible studies included other racial or ethnic groups (e.g., American Indian, Asian).

Health Outcome Variables

Cardiovascular measures included cardiometabolic biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), [22, 29] hypertension/blood pressure, [23, 29, 33, 52, 64] and having either a history of or dying from heart disease. [40, 43] Cognitive measures included single and multi-component tests of cognition [21, 24, 37, 44, 46, 57, 61] and neuroimaging assessments. [38, 44] Physical function measures included questionnaires and battery assessments of function, disability, and physical performance. 33,44,48,52 Mental health measures included measured and self-reported depression, [28, 31, 32, 34, 36, 49, 50, 53, 59, 60] self-reported mental health quality, [34, 39, 51] measured and self-reported mood, psychiatric or anxiety disorder, [34, 40, 45, 53] and measured psychological distress. [53, 54] Four studies exclusively assessed telomere length. [26, 27, 56, 62] General/other health measures included body mass index, [30, 35] health-related quality of life, [42, 51] premature mortality, [48] pain intensity, [58] and breast cancer subtype. [25, 47]

Racism Variables

Twenty-seven studies included measures of perceived interpersonal racism either alone or in combination with perceived institutional measures. Measures of perceived interpersonal racism included either a portion of or the entire Williams Everyday Discrimination Scale, [26,27,28,29, 31, 32, 34,35,36,37, 40, 42, 44, 45, 49, 50, 53,54,55,56,57, 60, 61] the Schedule of Racist Events (a portion of which assesses interpersonal experiences) and the General Ethnic Discrimination Scale adapted from it, [58, 59] and questions written either by the study authors or other cited authors about perceived interpersonal racism. [30, 41, 56]

Sixteen studies included measures of perceived institutional racism either alone or in combination with perceived interpersonal measures. Measures of perceived institutional racism included the Williams Major Experiences of Discrimination Scale, [22, 26, 27, 32, 34,35,36, 38, 40, 51, 56, 62] the Krieger Experiences of Discrimination Scale, [38, 56] the Schedule of Racist Events (a portion of which assesses institutional experiences) and the General Ethnic Discrimination Scale adapted from it, [58, 59] the Williams Workplace Discrimination Scale, [52] and questions written by the study authors about perceived institutional racism. [30]

Eight studies used indicators of racist policies or practices within one context to assess participant exposure to institutional racism. Institutional indicators included residential segregation (e.g., isolation index), [23, 25, 33, 43, 46] school segregation, [21, 24] school term length, [64] and number of recent police killings of unarmed Black Americans in the participant’s state of residence. [39]

Three studies assessed exposure to structural racism. All three measured whether a person was born/had resided in a Jim Crow state or region. [24, 47, 48] This was categorized as “structural” because Jim Crow laws affected a person across contexts (e.g., attending school, buying a home). One of these studies also assessed school segregation. [24]

Health Outcomes

Thirty-three of the 43 studies found a significant association between racism and health in Black adults aged 50 or older. Of these, 14 found significant associations between racism and mental health, [28, 32, 34, 36, 39, 45, 49,50,51, 53, 54, 58,59,60] seven for cognition, [21, 24, 37, 38, 44, 57, 61] five for cardiovascular outcomes, [22, 29, 33, 43, 64] three for physical function, [51, 55, 59] two for telomere length, [26, 62] and five for general/other health outcomes. [25, 42, 47, 48, 54] Specific significant findings are included below based on health category of dependent variable(s) and level of racism of independent variable(s). Unless specified otherwise, only statistically significant results found for older Black adults are included in the sections below.

Associations Between Racism and Mental Health

In studies that assessed mental health, interpersonal measures were significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms, [32, 36, 49, 50, 53, 58,59,60] psychological distress, [53, 54] worse self-reported mental health, [34] psychiatric disorders, [45, 53] mood disorders, [53] and anxiety. [53] For example, one study found that African American participants aged 60 years and older who reported experiencing discrimination “often” or “sometimes” on the Everyday Discrimination Scale were 20% more likely to report depressive symptoms on the CES-D after controlling for age, sex, education and income, as compared to those who reported experiencing discrimination “rarely” or “never.” [28] In another study, higher levels of everyday discrimination (measured continuously) were associated with worse mental health as reported on the SF36 Mental Health Component Summary. [34]

Five studies found significant associations between perceived institutional racism and mental health outcomes. A study that assessed the relationship between perceived institutional discrimination and health-related quality of life found that increased discrimination was associated with poorer mental health, one component of the quality of life scale. [51] Three studies that used measures of both interpersonal and institutional racism found an association with depression. [36, 58, 59]

One study assessed the relationship between an indicator of institutional racism and self-reported mental health. In that study, the number of police killings of unarmed Black Americans in the past three months was associated with an increase in poor mental health among participants aged 50–64 years (but not among those aged 65 and older). [39]

Associations Between Racism and Cardiovascular Health

One study found significant associations between interpersonal discrimination and cardiovascular health: Non-Hispanic Black participants who reported discrimination in the health care setting, using one item from the Everyday Discrimination Scale, had an increased likelihood of elevated CRP, elevated HbA1c, and elevated blood pressure. [29] Contrary to hypotheses, Black participants who reported discrimination in this study had lower levels of total cholesterol and lower levels of HDL compared to Black participants who did not report discrimination. [29]

One study found an association between perceived institutional discrimination and elevated CRP, an inflammatory biomarker linked with experiences of heightened stress. [22] In another, a 10% longer school term length was associated with lower systolic blood pressure, lower diastolic blood pressure, and lower risk of hypertension among Black women; there was no association in Black men. [64] Shorter term length is an indicator of discrimination against quality education particularly during the Jim Crow Era. In a third study using institutional indicators, researchers used a novel measure of residential segregation: Wong’s Local Index models the potential for interaction between people of the same and of different races. [33] Foreign-born Black participants aged 65 or older were 46% less likely to report hypertension if they lived in high-segregation areas than if they lived in low-segregation areas. Researchers did not find a significant association among US-born Black participants. [33] Conversely, a different study found that racial residential segregation was associated with heart disease mortality among Black people aged 65 and older. [43]

Associations Between Racism and Cognitive Health

Three studies found a significant association between everyday discrimination and poorer performance on one or more tests of cognition. [37, 57, 61] In addition, attending a segregated school as a child was associated with poorer language and perceptual speed scores in a battery of cognitive tests. [21] In this longitudinal study, there were no significant associations between school segregation and change in cognition over time or between school segregation and baseline global cognition, reasoning, or memory. [21] In another study, birth in the southern US predicted lower cognitive functioning, including lower levels of performance in episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed and visuospatial ability. [24] Southern US residence at age 12 years was associated with lower levels of global cognitive functioning and all cognitive domains except episodic memory. [24] Neither southern US residence at age 12 years nor birth in the southern US predicted change in cognition over time. School segregation status was not associated with either baseline levels or rates of change in any of the cognitive measures. [24]

Two studies assessed the relationship between perceived interpersonal or institutional discrimination and changes in brain imaging. One found that everyday discrimination was associated with stronger functional connectivity between the left insula and bilateral intracalcarine cortex, weaker functional connectivity between the left insula and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and weaker functional connectivity between the right insula and left supplementary motor cortex. [44] Another found that perceived institutional discrimination was associated with increased white matter legion volume. [38]

Associations Between Racism and Telomere Length

Of the four studies that assessed discrimination and telomere length, two found significant associations between discrimination and shorter telomere length (an indicator of biological aging). In one of the studies, major discrimination was associated with shorter telomere length among African American males and females aged 51 years and older after controlling for sociodemographic and health factors such as depressive symptoms and stress. [62] In the other, everyday discrimination was associated with shorter telomere length among non-Hispanic Black participants aged 50 years and older, though this association was not observed with experiences of major discrimination. [26]

Associations Between Racism and Physical Function

Three studies found an association between racism and physical function. In one, higher scores on a scale measuring both perceived interpersonal and perceived institutional racism were associated with disability, using functional limitations and disability questionnaires. [59] In another, perceived everyday discrimination was associated with worse physical functioning using the PROMIS physical functioning measure. [55] In the third, perceived institutional discrimination was associated with poor self-reported health. [51]

Associations Between Racism and General/Other Health Outcomes

We classified associations between racism and outcomes as “general/other health” if they were not otherwise categorized. One study found that neighborhood segregation was associated with decreased likelihood of high-risk breast cancer subtype, contrary to the hypothesis. [25] Another found that everyday discrimination was associated with worse overall health-related quality of life. [42] In a study using a measure of both perceived interpersonal and perceived institutional discrimination, discrimination was associated with greater pain intensity; this relationship was no longer significant after adding depression to the model and a mediation effect was detected. [58]

Two studies by the same first author assessed the relationship between birth in a Jim Crow state (an indicator of exposure to structural racism) and health outcomes. One study found that the odds of having more aggressive subtypes of cancer (ER − versus ER +) were higher for those born in a Jim Crow state. [47] The other found that residence in a Jim Crow state was associated with premature mortality for older Black Americans, and the relationship was strongest for those who were oldest during the Jim Crow Era (i.e., had greater degrees of exposure to Jim Crow policies over time). [48]

Study Design

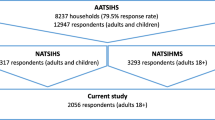

While 37 of the studies were cross-sectional in design, six were longitudinal. [21, 24, 46, 57, 60, 61] As indicated in Table 2, sample sizes for older Black American participants across all 43 included studies were categorized as small (n = < 100), medium (n = 100–1000), large (n = 1000–5000), and very large (n = 5000 +). Very large studies typically used census-tract data or other area-level variables. Many of the studies used data from the same large parent studies such as the Health and Retirement Study [22, 26, 29, 36, 46, 52, 60,61,62] and the Minority Aging Research Study. [28, 37, 44, 57]

Thirty-six of the studies used validated measures of discrimination and six [21, 29, 30, 33, 35, 41] did not (or did not provide evidence of psychometrics validation). One study used both a validated and an unvalidated measure. [24] Unvalidated measures included self-report of school segregation, [21, 24] a single question taken from a validated instrument (no validity or reliability statistics were provided), [29] a study-specific measure of perceived interpersonal and institutional racism (no validity or reliability statistics were provided), [30] a single question written by the study authors (no validity or reliability statistics were provided), [41] and a novel measure of racial segregation (no validity or reliability statistics were provided or could be found in the cited references). [33] Another study’s authors used terminology similar to the Williams Everyday and Major Experiences scales (both of which are widely validated [65]) when describing discrimination measurement, but did not name the scales used, cite them, or provide validity statistics; it is possible that this study used the validated scales. [35]

See Tables 1 and 2 for detailed study characteristics and results.

Discussion

Racism and Older Adult Health

The findings from this systematic review suggest that there are important associations between experiences of racism and older Black American adult health across categories of health outcomes and levels of racism. While there is a large and growing body of evidence regarding the relationship between racism and health outcomes, this review reveals a need for increased focus on this area in older adults specifically. Past reviews have found hundreds of articles examining racism and health in general populations, [11, 16] while this review identified just 43 articles that reported results exclusively or specifically in Black individuals aged 50 years and older. Considering the multi-level and long-term experiences with racism of many older adults, researchers should consider designing studies that exclusively sample an older adult population or specifically report results of the effects of racism on older adults within a broader population. Some of the results provided in this paper were found in online-only appendices; in studies of mixed-age populations, providing age-stratified results in supplemental materials could be a strategy for providing this important detail while staying within word limits set by publishers.

It is worth emphasizing that research focusing on “older adults” can include people from various age ranges beyond just 50 to 100 + years. However, researchers also look at no other life periods of the age spectrum with as broad of a reference point as they often do with older adults. It is important for researchers in future studies to examine the multilevel differences in exposure to racism and the effects that they have on health both within and between age cohorts of older adults.

Many older Americans today were born before the Jim Crow laws that formalized discriminatory policies and practices based on race were abolished and were also alive when the Social Security Act of 1935 enacted a social retirement benefit that systematically disadvantaged aging Black Americans. [5] All older adults today have witnessed and/or been directly impacted by contemporary racist policies and practices such as the disproportionate incarceration of Black Americans. [9] It is well established that social determinants of health such as the lack of access to resources (e.g., education and job opportunities), negative interpersonal experiences, living in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and other differences across opportunities adversely impact health. The studies in this review suggest that exposures to racism across the life course may be a root cause of many health disparities among older Black Americans.

While there is a need to increase the literature base on older adults and racism in general, there is a particular need for future studies to examine the impacts of racism on older adults across a wide variety of health outcomes and beyond self-reported measures. For example, just three of the studies we reviewed assessed physical function or a related construct (frailty, disability) [41, 55, 59] and only one of those administered an in-person physical assessment. [41] Frailty is an important predictor of healthcare spending and decline among older adults, [66] and its relationship with discrimination should be further—and more rigorously—evaluated.

Structural Measures

This review revealed an urgent need for the examination of the impact of structural racism in particular on older adult health. The lack of evidence in this area may be related to the lack of consensus regarding the delineation between levels of racism. For example, many researchers use the terms “institutional racism” and “structural racism” interchangeably whereas others, such as Bailey and colleagues, [5] assert that they are distinct concepts. Additionally, there are no widely tested and validated tools that comprehensively measure structural racism, making its study more difficult than the study of interpersonal racism. [7]

While several studies included in this review assessed exposure to institutional racism, most relied on self-reported measures of perception. Since assessing one’s own exposure to systemic forces presents many challenges, more attention is ultimately needed for considering objective measures of institutional and structural racism. Additionally, studies that assessed exposure to institutional racism using objective indicators most often used indicators of neighborhood segregation. No studies included in this review assessed exposure to racism using objective data sources in the contexts of civic life (e.g., voting wait times, government representation), employment, healthcare, media and marketing, environment, or income/credit/wealth. Studies of institutional racism should consider measuring within these contexts, as well as within education, policing, and neighborhood factors. There is a particular need for studies to assess exposures across multiple of these contexts to better measure the downstream effects from structural level racism.

Segregation is often relied upon as a single measure of exposure to racism but this may not be appropriate, particularly for foreign-born individuals. Some studies suggest that a high concentration of immigrants in a neighborhood may have health-protective effects through the promotion of social support enclaves. [21] This is one example that illustrates the importance of measuring across multiple contexts as one metric likely cannot capture a person’s full experiences with racism.

The three studies that did assess exposure to structural racism used state or region of birth (Jim Crow state/region or not). These are valuable contributions to the literature. Additional studies are needed that use institutional indicators from multiple time points in a person’s life (not just historic or just contemporary measures), and at greater geographic specificity (e.g., census tract) to improve understanding the relationship further between cumulative exposures to structural racism and health.

Multilevel Measures

Results from this review also demonstrate a need for increased use of multilevel measures of racism (i.e., measures across interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels). Eleven of the reviewed studies included measures across more than one level of racism, but all of those used measures of perceived interpersonal and institutional racism; none combined institutional or structural indicators with perceived racism. Theories of racism and discrimination make clear that experiences at one level may impact experiences at another and that there may be synergistic effects; [6] without more rigorous examination of this phenomenon through multi-level measures, the relevance of these theories to an older adult population will remain poorly understood. This issue reinforces the need for better measurement tools that can efficiently and effectively assess racism across contexts (e.g., education, employment, policing), time points, geographic granularities, and levels (i.e., interpersonal, institutional, structural).

Race of Participants

Another gap in the literature that this search revealed is a need for more racially diverse samples of older adults with analyses based on more nuanced categories. Since race is socially constructed, it may be important to examine differential impacts of racism based on more inclusive categories of race beyond just “Black” and “White.” For example, no studies in this search examined the impacts of variations in skin pigmentation/tone (i.e., effects of colorism) or of perceived versus self-identified race on older adults’ experiences with racism.

Most studies in this search compared Black participants to White participants or included Black participants only. Few studies included multiple minority groups and those that did only provided results specifically for Black participants, Hispanics of any race, and White participants. No studies specifically provided results for participants who identify as Asian American, American Indian, Pacific Islander, or mixed/multiple race. Given this study’s focus, we excluded any studies that did not provide results for Black participants, so while studies that only examined racism in Asian Americans, for example, do exist, [67, 68] they were intentionally excluded. It would be beneficial for future studies to provide results for older adults from other racial groups to enable better understanding of how racial discrimination differentially or similarly affects groups of older Americans.

Study Design

As in many areas of research, this review revealed that most published studies of racism and older adult health are cross-sectional. Since racism differentially affects cohorts of Americans due to compounding effects from living through multiple iterations of racist policies and cultural attitudes over a lifetime, there is an urgent need for longitudinal studies on this topic in this population.

Exclusion Based on Incarceration and Institutionalization

Many of the studies in this review specifically excluded individuals who were incarcerated or living in a long-term care setting (e.g., nursing home, group home). Among those that did not specifically exclude based on these criteria, none provided results for these groups specifically or made specific efforts to recruit in these populations. Racism is a particular concern in the criminal justice system and may be an important contributor to an older adult’s inability to age in place due to the impacts of redlining on homeownership and access to community resources. For these reasons, future studies should consider including or focusing on older adults experiencing incarceration or who are living in long-term care facilities.

Limitations

This review has many strengths, such as the use of a broad and inclusive search strategy. However, there are also some noteworthy limitations. Firstly, though two reviewers completed a title and abstract review to determine the eligibility of a study for inclusion, just one reviewer completed a full-text review to verify eligibility. It is possible that this resulted in some studies being inappropriately excluded. However, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria selected a priori should have mitigated this source of error. While this review supports the need for additional research on institutional and structural racism, a lack of conceptual clarity may also mean that more studies exist that measure racism at the institutional or structural level but that they were not identified in this search because they did not self-identify as such. For example, studies of voting laws that disproportionately impact one race may not use the terms “racism” or “discrimination” in their findings but may in fact be studying these phenomena.

Conclusion

Researchers in gerontology, public health, and the social sciences should improve measurements of racism and further investigate the relationship between all levels of racism and older Black Americans’ health to improve understanding of how and to what extent racism contributes to racial health disparities.

References

Thorpe RJ Jr, Koster A, Bosma H, et al. Racial differences in mortality in older adults: factors beyond socioeconomic status. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-011-9335-4.

Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, Mclemore MR. On racism : a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Heal Aff Blog. 2020:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347

Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight — reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874–82. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmms2004740.

Jones CP. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: launching a national campaign against racism. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(Suppl 1):231–4. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.28.S1.231.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389(10077):1453–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–5. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212.

Groos M, Wallace M, Hardeman R, Theall K. Measuring inequity: a systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2018;11(2).

Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34(1):181–209. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740.

Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30259-3.

Thorpe RJJ, Kelly-Moore JA. Life course theories of race disparities. In: LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, editors. Race, Ethnicity, and Health: a Public Health Reader. 2nd ed. San Francisco, C: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. p. 355–74.

Pascoe EA, Smart RL. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016059.

Torres L, Vallejo LG. Ethnic discrimination and Latino depression: the mediating role of traumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2015;21(4):517–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000020.

Cuffee Y, Hargraves J, Allison J. Exploring the association between reported discrimination and hypertension among African Americans: a systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2012;4:422–31.

Lee DL, Ahn S. Racial discrimination and Asian mental health: a meta-analysis. Couns Psychol. 2011;39(3):463–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010381791.

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511.

Dolezsar C, McGrath J, Herzig A, Miller S. Perceived discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(3):A-45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033718.

Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888–901. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl056.

Miller HN, LaFave S, Marineau L, Stephens J, Thorpe RJJ. The impact of discrimination on allostatic load in adults: an integrative review of literature. J Psychosom Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110434.

Arias E, Xu JQ. United States life tables, 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2020;69(12). National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD.

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Aiken-Morgan AT, Gamaldo AA, Sims RC, Allaire JC, Whitfield KE. Education desegregation and cognitive change in African American older adults. J Gerontol - Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(3):348–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu153.

Cobb RJ, Parker LJ, Thorpe RJ. Self-reported instances of major discrimination, race/ethnicity, and inflammation among older adults: evidence from the health and retirement study. J Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(2):291–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly267.

Cole H, Duncan DT, Ogedegbe G, Bennett S, Ravenell J. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage; neighborhood racial composition; and hypertension stage, awareness, and treatment among hypertensive Black men in New York City: does nativity matter? J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2017;4(5 PG-866–875):866–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0289-x.

Lamar M, Lerner AJ, James BD, et al. Relationship of early-life residence and educational experience to level and change in cognitive functioning: results of the minority aging research study. J Gerontol - Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(7):E81–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz031.

Linnenbringer E, Geronimus AT, Davis KL, Bound J, Ellis L, Gomez SL. Associations between breast cancer subtype and neighborhood socioeconomic and racial composition among Black and White women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180:437–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05545-1.

Liu SY, Kawachi I. Discrimination and telomere length among older adults in the United States: does the association vary by race and type of discrimination? Public Health Rep. 2017;132(2):220–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354916689613.

Lu D, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, et al. Perceived racism in relation to telomere length among African American women in the Black Women’s health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;36:33–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.06.003.

Nadimpalli SB, James BD, Yu L, Cothran F, Barnes LL. The association between discrimination and depressive symptoms among older African Americans: the role of psychological and social factors. Exp Aging Res. 2015;41(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2015.978201.

Nguyen TT, Vable AM, Glymour MM, Allen AM. Discrimination in health care and biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in U.S. adults. SSM - Popul Heal. 2019;7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.10.006

Vásquez E, Udo T, Corsino L, Shaw BA. Racial and ethnic disparities in the association between adverse childhood experience, perceived discrimination and body mass index in a national sample of U.S. older adults. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;38(1):6–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2019.1572569.

Watkins DC, Hudson DL, Caldwell CH, Siefert K, Jackson JS. Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21(3):269–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731510385470.Discrimination.

Wheaton FV, Thomas CS, Roman C, Abdou CM. Discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men across the adult lifecourse. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(2):208–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx077.

White K, Borrell LN, Wong DW, Galea S, Ogedegbe G, Glymour MM. Racial/ethnic residential segregation and self-reported hypertension among US- and foreign-born Blacks in New York City. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(8):904–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2011.69.

Yoon E, Coburn C, Spence SA. Perceived discrimination and mental health among older African Americans: the role of psychological well-being. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(4):461–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1423034.

Assari S. Psychosocial correlates of body mass index in the United States: intersection of race, gender and age. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2016;10(2):7. https://doi.org/10.17795/ijpbs-3458.

Ayalon L, Gum AM. The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(5):587–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.543664.

Barnes LL, Lewis TT, Begeny CT, Yu L, Bennett DA, Wilson RS. Perceived discrimination and cognition in older African Americans. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18(5):856–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617712000628.

Beatty Moody DL, Taylor AD, Leibel DK, et al. Lifetime discrimination burden, racial discrimination, and subclinical cerebrovascular disease among African Americans. Heal Psychol. 2019;38(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000638.

Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of Black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9.

Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Lincoln KD, Arriola KRJ. Racial discrimination, mood disorders, and cardiovascular disease among black Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(2):104–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.10.009.

Clay OJ, Thorpe RJ, Wilkinson LL, et al. An examination of lower extremity function and its correlates in older African American and white men. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(3):271–8. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.25.3.271.

Coley SL, Mendes de Leon CF, Ward EC, Barnes LL, Skarupski KA, Jacobs EA. Perceived discrimination and health-related quality-of-life: gender differences among older African AmericansTitle. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(12):3449–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1663-9.

Greer S, Kramer MR, Cook-Smith JN, Casper ML. Metropolitan racial residential segregation and cardiovascular mortality: exploring pathways. J Urban Heal. 2014;91(3):499–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-013-9834-7.

Han SD, Lamar M, Fleischman D, et al. Self-reported experiences of discrimination in older Black adults are associated with insula functional connectivity. Brain Imaging Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-020-00365-9

Kim G, Parmelee P, Bryant AN, et al. Geographic region matters in the relation between perceived racial discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black older adults. Gerontologist. 2017;57(6):1142–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw129.

Kovalchik SA, Slaughter ME, Miles J, Friedman EM, Shih RA. Neighbourhood racial/ethnic composition and segregation and trajectories of cognitive decline among US older adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(10):978–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-205600.

Krieger N, Jahn JL, Waterman PD. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: uS-born black and white non-Hispanic women, 1992–2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull BA, Beckfield J, Kiang MV, Waterman PD. Jim Crow and premature mortality among the US Black and White population, 1960–2009: an age–period–cohort analysis. Epidemiology. 2014;25(4):494–504. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000104.

Marshall-Fabien GL, Miller DB. Exploring ethnic variation in the relationship between stress, social networks, and depressive symptoms among older Black Americans. J Black Psychol. 2016;42(1):54–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798414562067.

Marshall GL, Rue TC. Perceived discrimination and social networks among older African Americans and Caribbean blacks. Fam Community Heal. 2012;35(4):300–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e318266660f.

McClendon J, Bogdan R, Jackson JJ, Oltmanns TF. Mechanisms of Black-White disparities in health among older adults: examining discrimination and personality. J Health Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319860180.

Mezuk B, Kershaw KN, Hudson D, Lim KA, Ratliff S. Job Strain, Workplace discrimination, and hypertension among older workers: the health and retirement study. Race Soc Probl. 2011;31(1):38–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-011-9041-7.

Mouzon DM, Taylor RJ, Keith VM, Nicklett EJ, Chatters LM. Discrimination and psychiatric disorders among older African Americans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(2):175–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4454.

Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Aranda MP, Lincoln KD, Thomas CS. Discrimination, serious psychological distress, and church-based emotional support among African American men across the life span. J Gerontol - Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(2):198–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx083.

Nkimbeng M, Commodore-Mensah Y, Angel JL, et al. Longer residence in the United States is associated with more physical function limitations in African immigrant older adults. J Appl Gerontol. December 2020:733464820977608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820977608

Pantesco EJ, Leibel DK, Ashe JJ, et al. Multiple forms of discrimination, social status, and telomere length: interactions within race. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;98(August):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.08.012.

Pugh E, De Vito A, Divers R, Robinson A, Weitzner DS, Calamia M. Social factors that predict cognitive decline in older African American adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(3):403–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5435.

Taylor JLW, Campbell C, Thorpe RJJ, Whitfield KE, Nkimbeng M, Szanton SL. Pain, Racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms among African American women. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(1):79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2017.11.008.

Walker JL, Harrison TC, Brown A, Thorpe RJJ, Szanton SL. Factors associated with disability among middle-aged and older African American women with osteoarthritis. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(3):510–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.02.004.

White K, Bell BA, Huang SJ, Williams DR. Perceived discrimination trajectories and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Black adults. Innov Aging. 2020;4(5):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa041.

Zahodne LB, Sol K, Kraal Z. Psychosocial pathways to racial/ethnic inequalities in late-life memory trajectories. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(3):409–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx113.

Lee DB, Kim ES, Neblett EWJ. The link between discrimination and telomere length in African American adults. Heal Psychol. 2017;36(5):458–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000450.

Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works — racist policies as a root cause of u.s. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmms2025396.

Liu SY, Manly JJ, Capistrant BD, Glymour MM. Historical differences in school term length and measured blood pressure: contributions to persistent racial disparities among US-born adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129673.

Williams DR. Measuring Discrimination Resource. 2016. Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/davidrwilliams/files/measuring_discrimination_resource_june_2016.pdf.

Alecxih L. Shen S, Chan I, Taylor D, Drabek J. Individuals living in the community with chronic conditions and functional limitations: A closer look. United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/75961/closerlook.pdf

Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: the impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(3):787–800. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787.

Li LW, Gee GC, Dong XQ. Association of self-reported discrimination and suicide ideation in older Chinese Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(1):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.08.006.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1DP1AG069874-01). S.E. LaFave was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (TL1-TR003100), the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (T32AG066576), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars Program. J.J. Suen was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (F31AG071353) and the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. M.C. Fisher was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (1F31NR019211) and the Sigma/Hospice and Palliative Nurses Foundation End-of-Life Nursing Care Research Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

LaFave, S.E., Suen, J.J., Seau, Q. et al. Racism and Older Black Americans’ Health: a Systematic Review. J Urban Health 99, 28–54 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00591-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00591-6