Abstract

Purpose

It is unknown whether Jim Crow—i.e., legal racial discrimination practiced by 21 US states and the District of Columbia and outlawed by the US Civil Rights Act in 1964—affects US cancer outcomes. We hypothesized that Jim Crow birthplace would be associated with higher risk of estrogen-receptor-negative (ER−) breast tumors among US black, but not white, women and also a higher black versus white risk for ER− tumors.

Methods

We analyzed data from the SEER 13 registry group (excluding Alaska) for 47,157 US-born black non-Hispanic and 348,514 US-born white non-Hispanic women, aged 25–84 inclusive, diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer between 1 January 1992 and 31 December 2012.

Results

Jim Crow birthplace was associated with increased odds of ER− breast cancer only among the black, not white women, with the effect strongest for women born before 1965. Among black women, the odds ratio (OR) for an ER− tumor, comparing women born in a Jim Crow versus not Jim Crow state, equaled 1.09 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06, 1.13), on par with the OR comparing women in the worst versus best census tract socioeconomic quintiles (1.15; 95% CI 1.07, 1.23). The black versus white OR for ER− was higher among women born in Jim Crow versus non-Jim Crow states (1.41 [95% CI 1.13, 1.46] vs. 1.27 [95% CI 1.24, 1.31]).

Conclusions

The unique Jim Crow effect for US black women for breast cancer ER status underscores why analysis of racial/ethnic inequities must be historically contextualized.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Murray P (1950) States’ laws on race and color. Women’s Division of Christian Services, Athens, Georgia

Wilkerson I (2010) The warmth of other suns: the epic story of America’s Great Migration. Vintage Books, New York City, New York

Krieger N (2011) Epidemiology and the people’s health: theory and context. Oxford University Press, New York City, New York

Almond D, Chay KY (2008) The long-run and intergenerational impact of poor infant health: evidence from cohorts born during the Civil Rights era. Working Paper. http://users.nber.org/~almond/chay_npc_paper.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2016

Kaplan G, Ranjit N, Burgard S (2008) Lifting gates, lengthening lives: Did civil rights policies improve the health of African-American women in the 1960s and 1970s? In: Schoeni RF, House JS, Kaplan G, Pollack H (eds) Making Americans Healthier: social and economic policy as health policy. Russell Sage Foundation, New York City, New York, pp 145–170

Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull B, Waterman PD, Beckfield J (2013) The unique impact of abolition of Jim Crow laws on reducing health inequities in infant death rates and implications for choice of comparison groups in analyzing societal determinants of health. Am J Public Health 103:2234–2244

Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull BA, Beckfield J, Kiang MV, Waterman PD (2014) Jim Crow and premature mortality among the US black and white population, 1960–2009: an age-period-cohort analysis. Epidemiol 25:494–504

Cunningham SA, Ruben JD, Narayan KMV (2008) Health of foreign-born people in the United States. Health Place 14:623–635

Andreeva VA, Unger JB, Pentz MA (2007) Breast cancer among immigrants: a systematic review and new research directions. J Immigr Minor Health 9:307–322

Krieger N (2013) History, biology, and health inequities: emergent embodied phenotypes and the illustrative case of the breast cancer estrogen receptor. Am J Public Health 103:22–27

Potischman N, Troisi R, Vatten L (2004) A life course approach to cancer epidemiology. In: Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y (eds) A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 260–280

Carpenter DO, Bushkin-Bedient S (2013) Exposure to chemicals and radiation during childhood and risk for cancer later in life. J Adolesc Health 52:S21–S29

Bernstein L, Teal CR, Joslyn S, Wilson J (2003) Ethnicity-related variation in breast cancer risk factors. Cancer 97(Suppl 1):222–229

Palmer JR, Ambrosone CB, Olshan AF (2014) A collaborative study of the etiology of breast cancer subtypes in African American women: the AMBER consortium. Cancer Causes Control 25:309–319

Borrell LN, Castor D, Conway FP, Terry MB (2006) Influence of nativity status on breast cancer risk among U.S. Black women. J Urban Health 83:211–220

Howe HL, Alo CJ, Lumpkin JR, Qualls RY, Lehnherr M (1997) Cancer incidence and age at northern migration of African Americans in Illinois, 1986–1991. Ethn Health 2:209–221

Coates AS, Winer EP, Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Gnant M, Piccart-Gebhart, Thürlmann B, Senn H-J, Panel Members (2015) Tailoring therapies—improving the management of early breast cancer: St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2015. Ann Oncol 26:1533–1546

Kohler BA, Sherman RL, Howlader N, Jemal A, Ryerson AB, Henry KA, Boscoe FP, Cronin KA, Lake A, Noone A-M, Henley SJ, Eheman CR, Anderson RN, Penberthy L (2015) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty and state. JNCI 107(6):djv048

Akinyemiju TF, Pisu M, Waterbor JW, Altekruse SF (2015) Socioeconomic status and incidence of breast cancer by hormone receptor status. SpringerPlus 4:508. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1282-2

Sineshaw HM, Gaudet M, Ward EM, Flanders WD, Desantis C, Lin CC, Jemal A (2014) Association of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer subtypes in the National Cancer Data Base (2010–2011). Breast Cancer Res Treat 145:753–763

Daly B, Olopade OI (2015) A perfect storm: how tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin 65:221–238

Dietze EC, Sistrunk C, Miranda-Carboni G, O’Regan R, Seewaldt VL (2015) Triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: disparities versus biology. Nat Rev Cancer 15:248–254

Newman LA (2015) Disparities in breast cancer and African ancestry: a global perspective. Breast J 21:133–139

Eng A, McCormack V, dos-Santos-Silva I (2014) Receptor-define subtypes of breast cancer in indigenous populations in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 11(9):e1001720. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001720

Martinez ME, Cruz GI, Brewster AM, Bondy ML, Thompson PA (2010) What can we learn about disease etiology from case-case analyses? Lessons from breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 19:2710–2714

Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Lin YD, Johnson NJ, Schwartz SM, Bernstein L, Chen VW, Goodman MT, Gomez SL, Graff JJ, Lynch CF, Lin CC, Edwards BK (2007) Quality of race, Hispanic ethnicity, and immigrant status in population-based cancer registry data: implications for health disparity studies. Cancer Causes Control 18:177–187

Pinheiro PS, Bungum TJ, Jin H (2014) Limitations in the imputation strategy to handle missing nativity data in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program (letter). Cancer 120:3261

CDC Wonder (2016) Scientific data documentation. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER), 1973–1989. http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/sci_data/seer/type_txt/seer.asp. Accessed 1 Oct 2016

National Cancer Institute (2016) Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) data documentation and variable recodes. http://seer.cancer.gov/analysis/. Accessed 1 Oct 2016

Harel O, Zhou X-H (2007) Multiple imputation: review of theory, implementation, and software. Stat Med 26:3057–3077

Lee KJ, Carlin JB (2010) Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. Am J Epidemiol 171:624–632

Kenward MG, Goetghebeur EJT, Molenberghs G (2001) Sensitivity analysis for incomplete categorical data. Stat Model 1:31–48

Egleston BL, Wong Y-N (2009) Sensitivity analysis to investigate the impact of a missing covariate on survival analyses using cancer registry data. Stat Med 28:1498–1511

Yu M, Tatalovich Z, Gibson JT, Cronin KA (2014) Using a composite index of socioeconomic status to investigate health disparities while protecting the confidentiality of cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control 25:81–92

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader M-J, Subramanian SV, Carson R (2002) Geocoding and monitoring US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter? The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol 156:471–482

Krieger N, Chen JT, Ware JH, Kaddour A (2008) Race/ethnicity and breast cancer estrogen receptor status: impact of class, missing data, and modeling assumptions. Cancer Causes Control 19:1305–1318

Howlader N, Noone AM, Yu M, Cronin KA (2012) Use of imputed population-based cancer registry data as a method of accounting for missing information: application to estrogen receptor status for breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 176:347–356

Goldstein H (2011) Multilevel statistical models, 4th edn. Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey

Berglund P, Heeringa SG (2014) Multiple imputation of missing data using SAS. SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina

US Census Bureau (2007) Census atlas of the United States, Chapter 7: Migration. US Census Bureau, Washington. https://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/censusatlas/pdf/7_Migration.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2016

Aisch G, Gebeloff R, Quealy K (2014) Where we came from and where we went, state by state (1900–2012). New York Times (19 Aug 2014). http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/08/13/upshot/where-people-in-each-state-were-born.html?_r=0. Accessed 1 Oct 2016

Quadango J (2000) Promoting civil rights through the welfare state: how medicare integrated Southern hospitals. Soc Probl 47:68–89

Smith DB (1993) The racial integration of health facilities. J Health Polit Policy Law 18:851–869

Spracklen CH, Wallace RB, Sealy-Jefferson S, Robinson JG, Freudenheim JL, Wellons MF, Saftlas AF, Snetselaar LG, Manson JE, Hou L, Qi L, Chlebowski RT, Ryckman KK (2014) Birth weight and subsequent risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 38:538–543

Dunn BK, Agurs-Collins T, Browne D, Lubet R, Johnson KA (2010) Health disparities in breast cancer: biology meets socioeconomic status. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121:281–292

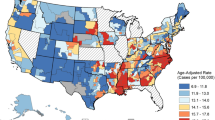

National Cancer Institute (2016) Cancer mortality maps, 1950–2004. http://ratecalc.cancer.gov/ratecalc//. Accessed 1 Oct 2016

Sighoko D, Fackenthal JD, Hainaut P (2015) Changes in the pattern of breast cancer burden among African American women: evidence based on 29 states and the District of Colombia during 1998 to 2010. Ann Epidemiol 25:15–25

Tian N, Gaines WJ, Benjamin ZF (2010) Female breast cancer mortality clusters within racial groups in the United States. Health Place 16:209–218

Sariego J (2009) Patterns of breast cancer presentation in the United States: Does geography matter? Am Surg 75:545–549

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professorship, awarded to N. Krieger.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author contributions

NK conceived the study, arranged access to the SEER custom data set, designed and supervised the analyses, and drafted the manuscript; JJ managed the study database, conducted the data analysis, and contributed to the manuscript; PDW assisted with obtaining the data and contributed to the data analysis and to the manuscript; all authors reviewed and approved the final version prior to submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

IRB approval

Approved as exempt (HSPH IRB Protocol #IRB13-1796), given use of public access de-identified data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krieger, N., Jahn, J.L. & Waterman, P.D. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: US-born black and white non-Hispanic women, 1992–2012. Cancer Causes Control 28, 49–59 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2