Abstract

Children are more likely to become addicted as they become accustomed to using smartphones, and as they observe and imitate their parents using smartphones. This study aims to confirm longitudinally the effect of mother’s smartphone addiction on children’s smartphone addiction. Latent growth modeling was used to analyze longitudinal relationships between 3615 pairs of children and their mothers from the Korean Children and Youth Panel Survey (KCYPS) (2018–2020). As a result, both the mothers and children’s smartphone addiction significantly increased over time. The initial value of the mother’s smartphone addiction was found to have a significant effect on the child's initial value and the change rate. Moreover, children’s smartphone addiction change rate was significantly affected by the change rate of the mother’s smartphone addiction. To intervene in children’s smartphone addiction, a family-level approach, as well as parental addiction, must also be addressed, and a preventive approach should focus on those with a low risk of addiction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In our society, smartphones have already taken hold due to the convenience and usefulness of providing tailored programs to meet specific user needs. As a result, our lives have become more and more dependent on smartphone technology in recent years. This shift has resulted in smartphones being used for digital healthcare and online education, which have become major social functions (Alhat, 2020; Almallah & Doyle, 2020), as well as playing a role in activating social networks and alleviating loneliness (Iyengar et al., 2020; Wetzel et al., 2021).

There has been much discussion regarding the negative and devastating effects of smartphones as well as their benefits. Similarly, although smartphones are claimed to have a negative relationship with mental health (Twenge et al., 2020), the relationship is still in active discussion (Twenge et al., 2020). However, the scientific evidence for the negative effects of smartphones is clearer when considering the user’s situation or personal characteristics, such as the risk of a driver’s traffic accident (Sánchez, 2006), child development, or behavior-related issues (Derevensky et al., 2019; Fecteau & Munoz, 2006; Pereira et al., 2020).

Moreover, mixed results of smartphone usage in previous studies are due to the different conceptual definitions and measurement methods. Though there is no consensus definition of smartphone addiction, it is regarded as one of the behavioral addictions such as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, tolerance, and compulsive behaviors (Kim, Lee, Lee, Nam & Chung, 2014). While behavioral addiction refers to an addiction to specific behaviors such as overeating, exercising, and games in a state where no substances are involved, media-related addictions, such as the Internet are sometimes classified as technology addiction, as the field of video media or technological development expands (Griffiths, 1995, 1998). Considering the conceptual definition of behavioral addiction and the smartphone addiction category, smartphone addiction cannot be self-regulating for problematic use, and it can be suggested to be defined as a state that interferes with daily activities as a result of compulsive, chronic usage. Conversely, since there are no strict standardized criteria for diagnosing smartphone addiction and reported problems with smartphone use are not synonymous with the existence of addiction (Panova et al., 2018), there are problems associated with this for using alternative terms, such as problematic smartphone use (Kuss et al., 2018) or self-reported dependence on mobile phones (Lopez-Fernandez et al., 2015).

However, it is worth noting that smartphone problematic use is still associated with negative outcomes and can be understood in various contexts of users. In this point of view, the smartphone addiction prevention approach for adolescents in a society with a high smartphone addiction problem compared to other countries will have great value in solving potential problems and establishing meaningful policy agendas; one of the representative countries is South Korea. A systematic review of 31 papers conducted by Sohn et al. (2019) found that overall child addiction prevalence rates ranged between 10 and 30% in the world. However, according to a survey by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) and the National Information Society Agency (NIA) of Korea in 2022, the proportion of Korean children (ages 10 to 19) in the risk group for the dependence on the smartphones was higher (37.0%), compared with 23.3% for adults (MSIT & NIA, 2022). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the children group showed the steepest increase compared to other age groups of 6.8% from 30.2% in the risk group in 2019 (MSIT & NIA, 2022).

While children depend on their parents, they are also undergoing a developmental process to establish their own identity (Ting & Chen, 2020). As they become more accustomed to technology that allows them to communicate with their peers through their smartphones, they may be exposed to a high risk for smartphone addiction (Cha & Seo, 2018). Furthermore, because the first few years of a child’s life determine their lifelong trajectories, we should pay attention to their smartphone addiction during this period. Previous studies have shown that smartphone addiction in children neurologically causes attention deficits (Kim et al., 2019) and affects emotional inhibition and impulsivity (Chen et al., 2016). Moreover, it has been reported to cause psychological problems such as social anxiety and loneliness (Elhai et al., 2017), as well as sleep disturbances and serious disruption in daily life and social activities (Randler et al., 2016) due to compulsive use.

Studies of predictive factors have been progressed as attention is taken into account when studying children’s smartphone addiction. Psychosocial factors (Lee et al., 2017), parents (Lee & Lee, 2017), and peers (Kim et al., 2018) have been reported as risk factors on smartphone addiction among children. It is particularly important to emphasize the role of parents, who have a more substantial effect on children’s behavior, such as contributing to or preventing smartphone addiction in children (Lee & Lee, 2017).

Indeed, particularly, parental smartphone addiction predicts child smartphone addiction. In light of social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977), the likelihood of addiction increases when children learn and imitate their parents’ smartphones usage, as children are influenced by their parents’ behavior (Kim et al., 2022). In one sense, parenting patterns including attachment or anxiety can cause children to be addicted to smartphones. For instance, when parents are stressed or depressed, they may neglect their children and loosely regulate their smartphone use (Kim et al., 2021). Although the mechanisms for smartphone addiction in children are interpreted differently by these two arguments, it is reasonable to believe that parents and children are closely connected in terms of smartphone addiction, based on the two mainstream arguments above. This relationship can be understood through the theory of imitation (Meltzoff, 2007; Meltzoff & Moore, 1977). In some empirical studies, it has been demonstrated that children can observe and mimic the behavior of their parents without any special stimulation. Moreover, parental influence on children’s smartphone addiction is also supported by mirror neuron theory (Son et al., 2021). This theory refers to the activity that the nerve cells called mirror neurons that convert the actions of others into neural signals and activate the actions of others through mirroring (Rizzolatti et al., 2010). The mirror neurons focus on observing the actions of others without making a distinction between not using the tool and tool-using behaviors; in this manner, it is possible to draw technical inferences about how to use a tool such as a smartphone by observing how others use it (Reynaud et al., 2019). However, mirror neurons interfere with reasoning about the intentions and psychological reasons underlying the observed behavior (Rizzolatti et al., 2010). Particularly in the case of children, the possibility of mirroring and activating the parent’s smartphone addiction behavior without a screening process is relatively high, as their cognitive judgment is not yet mature.

Theoretically, parental smartphone addiction can be predicted as a strong risk factor for children’s smartphone addiction (Bornstein, 2012). However, in general, it is considered that mothers spend more time in contact with their children than fathers and play a central role in raising children (Collins & Russell, 1991). When the social learning theory and mirror neuron theory are applied, in spite of inferring the relative strength of mother–child interaction compared to father-child interaction in children’s smartphone addiction, smartphone-related studies (Matthes et al., 2021; Son et al., 2021) have been not distinguished between fathers and mothers, and detailed considerations on the influence of mothers were not addressed.

A few studies (Kim et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2021; Lee & Lee, 2017; Song et al., 2019) have investigated the relationship between parents and children in smartphone addiction on the basis of these claims. It is difficult to confirm the evolution of addiction and the relationship over time since studies on the parent–child relationship in smartphone addiction were mostly based on cross-sectional approaches. This study, therefore, examines the longitudinal relationship between mothers’ smartphone addiction and children’s smartphone addiction within the context of Korea, which reports a relatively high level of smartphone penetration.

Methods

Data

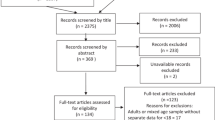

This study was analyzed using the Korean Children and Youth Panel Survey (KCYPS) conducted by the Korea National Youth Policy Institute. KCYPS is a representative survey of children and adolescents in Korea and their parents, providing basic data for establishing policies related to children and adolescents by establishing panel data that can comprehensively understand changes in the growth and development of children and adolescents. As of 2018, KCYPS conducted surveys on 5197 students and their parents (2607 students in 4th-grade elementary school, 2590 students in 1st-grade middle school). Three-year data from the first survey (2018–2020) and the third survey (2020) were used to analyze elementary school students (4th–6th grade), middle school students (1st–3rd grade), and their mothers. The KCYPS survey has been conducted from August to November every year. The final analysis included 3615 children (1752 elementary school students, 1863 middle school students) and 3615 mothers with no missing values in the main variables.

Variables

The dependent and independent variables of this study are smartphone addiction of children and mothers. According to the Korean Children and Adolescents Panel Survey, the Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale (SAPS) developed by Kim, D. et al. (2014) was used as a reference. The smartphone addiction self-diagnosis scale is comprised of 15 items on a 4-point scale (highly disagree = 1, somewhat disagree = 2, somewhat agree = 3, highly agree = 4). Out of the 15 questions, “using a smartphone does not interfere with what I am currently doing (studying),” “I do not feel anxious even without a smartphone,” and “I do not spend a lot of time using a smartphone” were reverse-coded. The average of the items was calculated. Higher scores indicate greater smartphone addiction. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for smartphone addiction among children was 0.884 in 2018, 0.872 in 2019, and 0.885 in 2020 and for smartphone addiction among mothers was 0.862 in 2018, 0.862 in 2019, and 0.869 in 2020.

Statistical Analysis

This study conducted a longitudinal analysis of mothers’ smartphone addiction and children’s smartphone addiction using the following methods and procedures. For data handling and model analysis, SPSS version 27.0 and M-plus 8.0 programs were used. We first performed a descriptive analysis to determine the characteristics of major variables. Secondly, latent growth modeling was conducted to estimate changes in smartphone addiction between mothers and children and to verify the relationship between the two. Lastly, to determine the model fit, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were used.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

According to Table 1, the mother’s smartphone addiction steadily increased from an average of 1.78 points (standard deviation [SD] = 0.43) in 2018 to an average of 1.91 points (SD = 0.44) in 2020. In addition, children’s smartphone addiction showed a similar tendency; it increased from 2018 (Mean [M] = 1.92, SD = 0.50) to 2020 (M = 2.15, SD = 0.51).

Model analysis

In this study, the potential growth model was analyzed in two stages. In the first stage, the initial value and change rate of smartphone addiction in mothers and children are estimated with the analysis of unconditional model. In the second stage, using the initial value and change rate obtained in the first stage, the relationship between changes in mothers’ smartphone addiction and children’s smartphone addiction was examined.

Analysis of Unconditional Model

Firstly, an unconditional model analysis was conducted to understand the changes in smartphone addiction among mothers and children before proceeding with the conditional model analysis (Table 2). Through the unconditional model, the no growth model and linear growth model were analyzed in order to identify the optimal change pattern. The no growth model assumes that the smartphone addiction will not change over time, while in the linear growth model, it is based on the assumption that smartphone addiction will increase or decreases showing a constant pattern over time. The model fit criteria are CFI, TLI, and RMSEA; specifically, if the CFI and TLI are 0.9 or above (Bentler & Bonett, 1980), and the RMSEA is less than 0.1, the model is judged to be appropriate (Browne & Cudeck, 1992).

Following the analysis, the mother’s smartphone addiction (χ2 = 24.386 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.987, TLI = 0.962, RMSEA = 0.068) and the child’s smartphone addiction (χ2 = 6.556 (p < 0.05), CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.039) showed that the linear growth model better explained the change in smartphone addiction than the no growth model; therefore, the linear growth model was selected (Table 2).

According to the results of the final selected unconditional linear growth model, the average initial smartphone addiction scores for mothers and children were 1.790 (p < 0.001) and 1.924 (p < 0.001), respectively (Table 3). The rate of change was 0.067 (p < 0.001) for mothers and 0.116 (p < 0.001) for children, indicating that the rate of change in smartphone addiction in children was slightly higher. Nevertheless, both the average and the change rate of smartphone addiction among mothers and children were significant, indicating that smartphone addiction increases over time. In addition, the variance of smartphone addiction among mothers and children was found to be significant both at the initial value and at the rate of change, indicating that there is a significant difference in the initial level and rate of change of smartphone addiction between the two.

The correlation between the initial value of smartphone addiction and the rate of change was significantly negative for both mothers and children, and it was confirmed that the group with the higher initial value of smartphone addiction increased less than the group with the lower initial value.

Analysis of Conditional Model

In the conditional model analysis, we examined how the initial value and rate of change of a mother’s smartphone addiction affect the initial value and rate of change of a child’s smartphone addiction. As a result of conditional model fit analysis, it was found that the model showed appropriateness for analysis (χ2 = 211.198 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.929, TLI = 0.917, RMSEA = 0.082).

Table 4 and Fig. 1 show the relationship between the initial value and the rate of change of mother’s and children’s smartphone addiction. The initial value of the mother’s smartphone addiction was found to have a significant effect on the child’s smartphone addiction initial value (Coef. = 0.254, p < 0.001) and the change rate (Coef. = 0.109, p < 0.05). In other words, it was analyzed that the higher the mother’s smartphone addiction in the early stage, the higher the child’s smartphone addiction, and the sharp increase in children’s smartphone addiction over time.

Moreover, children’s smartphone addiction change rate was significantly affected by the change rate of the mother’s smartphone addiction (Coef. = 0.893, p < 0.01). In other words, the child’s smartphone addiction also increased sharply with the passage of time as the mother’s addiction did. Thus, the results confirmed that as mothers’ smartphone addiction gradually increased, children’s smartphone addiction gradually increased as well.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to longitudinally confirm the effect of the mother’s smartphone addiction on children’s smartphone addiction. For this purpose, data from KCYPS targeting children and adolescents in Korea which has a high level of smartphone penetration was used. Latent growth modeling was used to analyze longitudinal relationships between 3615 pairs of children from elementary and middle schools and their mothers from 2018 to 2020. The main research findings derived and the main issues to be discussed are as follows.

Over time, both mothers and children reported increasing levels of smartphone addiction. The average of the initial values was higher and the rate of change was higher in children than in adult mothers; therefore, it was confirmed that children’s smartphone addiction could lead to serious consequences. This is consistent with a previous study which reported that children (ages 10 to 19) had the highest percentage of smartphone addiction risk group and showed the steepest increase compared to other age groups (MSIT & NIA, 2022). This shows the seriousness of smartphone addiction among children, and at the same time shows that measures to reduce its need to be taken.

These results are not only limited specifically to Korea. Globally, smartphone ownership by children has increased (OECD, 2017), and Sohn et al. (2019) reviewed studies related to problematic smartphone usage (PSU) in Europe, Asia, and the USA; 10 to 30% of the prevalence of smartphone addiction has been reported. In addition, mothers who are adult parents also showed an increase in their level of smartphone addiction longitudinally, indicating that mothers also have a risk of aggravating their addiction. Considering that the period of COVID-19 was included in the analysis, it is inevitable to not exclude the impact of the pandemic in this study. However, the seriousness of the addiction problem is being highlighted as the Internet and smartphone use rapidly increases as a result of the abrupt environmental change due to COVID-19 (Daglis, 2021). As a result, both parents and their children have increased their dependence on smartphones in this study, indicating that smartphone addiction is a problem that may exacerbate in the future due to the pandemic.

As a result of examining the correlations between the initial value of smartphone addiction and the rate of change, both mothers and children were significantly negative. This means that the group with a high initial value of smartphone addiction increases less than the group with a low initial value, and the group with a low initial value of smartphone addiction increases more than the group with a high initial value. Therefore, the result of the study shows that the group with a low level of addiction in the early stages may rapidly increase their level of addiction with the passage of time. These results indicate that interventions targeting high-risk groups are important for smartphone addiction interventions, but also addressing those with low addiction levels is critical. While smartphone addiction may not seem like a serious problem now, it is necessary to take a preemptive intervention and preventive approach to prevent it from escalating.

Finally, we found that a mother’s smartphone addiction had a longitudinal effect on children’s smartphone addiction. The mother’s initial value of smartphone addiction affected both the initial value and rate of change in the children’s addiction, and the mother’s change rate of smartphone addiction had a significant effect on the child’s change rate of smartphone addiction. In other words, a mother’s high smartphone addiction level predicts the child’s high smartphone addiction level as well as a rapid increase over time. If the mother’s smartphone addiction increases rapidly, the child’s smartphone addiction will also increase steeply accordingly. Indeed, according to previous studies, the effects of parents’ smartphone addiction on their children have been extensively studied (Kim et al., 2022; Lee & Lee, 2017; Son et al., 2021). In this study, this has once again been confirmed longitudinally and can be utilized as the result of this study to be in evidence to emphasize that parental smartphone addiction is an important intervention target.

However, traditionally parents’ role in guiding children’s smartphone addiction was dominant (Putra et al., 2022), while there has been limited consideration of their role as primary targets of children’s smartphone addiction. This study’s findings regarding the smartphone addiction patterns of adult parents and the longitudinal impact on children indicate that adult parents should be considered an addiction subject as well as the importance of intervention. Unfortunately, however, existing studies on smartphone addiction for adults are mostly limited to college students and office workers (Olson et al., 2021), and intervention in addiction is also treated less important than children and adolescents (Kim, 2020).

The longitudinal results presented in this study provide several implications for smartphone addiction-related interventions. Furthermore, the global COVID-19 pandemic situation is working as a double-edged sword of addiction, while the importance of communication via smartphones is highlighted (Yu & Liu, 2019). As a matter of fact, it is observed that among those who have experienced self-isolation, telecommuting, and online classes as a result of COVID-19, the smartphone dependence risk group and high-risk group account for a higher proportion than the general user group, and rather than the overdependence risk group, general users are utilizing smartphones as a way to control their children (MSIT & NIA, 2022). The prevention of smartphone addiction is urged more than ever, but research on prevention and treatment is lacking in comparison (Liu, 2021). This study is expected to provide a practical basis for the prevention and treatment of smartphone addiction in children.

Due to the use of secondary data, this study has limitations; the number of fathers’ cases was insufficient so we could not analyze them together with their mothers. Therefore, it may be difficult to generalize as the parent’s case. In this study, fathers were not considered, although they may influence their children as primary parent as well. To determine the ultimate impact of all caregivers in the home, it is recommended to proceed in a direction that involves all of the parties involved. In addition, the last data in this study (2020) was gathered after the outbreak of COVID-19, and considering the impact of the pandemic on smartphone addiction, it is possible that this might have impacted the study. It is suggested that further study should be conducted with a long-term perspective in order to consider the impact of COVID-19 on smartphone addiction. Moreover, this study examined the effects of parental smartphone addiction on children based on previous research and theories. It is also significant to examine the reversed effect and the details of the mechanisms of how parents and children become addicted to smartphones. Follow-up studies that utilize a variety of research methods and variables for preventing and intervening in smartphone addiction are suggested to be discussed. The significance of this study lies in its ability to clarify the effects of smartphone addiction among Korean children and their mothers, who have the highest smartphone penetration rate, through a longitudinal review rather than a cross-sectional analysis.

Conclusions

This study shows that a mother’s smartphone addiction influenced her children’s smartphone addiction. The result of this study suggests that in order to intervene in children’s smartphone addiction, the study stresses the importance of a family-level approach, and parental addiction must also be addressed. In addition, a preventive approach should target those with a low risk of addiction.

References

Alhat, S. (2020). Virtual classroom: A future of education post-COVID-19. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(4), 101–104.

Almallah, Y. Z., & Doyle, D. J. (2020). Telehealth in the time of Corona: ‘Doctor in the house.’ Internal Medicine Journal, 50(12), 1578–1583. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15108

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bornstein, M. H. (2012). Caregiver responsiveness and child development and learning: From theory to research to practice. In P. L. Mangione (Ed.), Infant/toddler caregiving: A guide to cognitive development and learning (2nd ed., pp. 11– 25). California Department of Education

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

Cha, S. S., & Seo, B. K. (2018). Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: Prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychology Open, 5(1), 2055102918755046. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102918755046

Chen, J., Liang, Y., Mai, C., Zhong, X., & Qu, C. (2016). General deficit in inhibitory control of excessive smartphone users: Evidence from an event-related potential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00511

Collins, W. A., & Russell, G. (1991). Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review, 11(2), 99–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(91)90004-8

Daglis, T. (2021). The Increase in Addiction during COVID-19. Encyclopedia, 1(4), 1257–1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia1040095

Derevensky, J. L., Hayman, V., & Gilbeau, L. (2019). Behavioral addictions: Excessive gambling, gaming, Internet, and smartphone use among children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics, 66(6), 1163–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2019.08.008

Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 251–259.

Fecteau, J. H., & Munoz, D. P. (2006). Salience, relevance, and firing: A priority map for target selection. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(8), 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.06.011

Griffiths, M. D. (1995). Technological addictions. Clinical Psychology Forum, Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychological Society, 76, 14–19.

Griffiths, M. D. (1998). Internet addiction: Does it really exist? In J. Gackenbach (Ed.), Psychology and the Internet: Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Transpersonal Inmplications. Academic Press.

Iyengar, K., Upadhyaya, G. K., Vaishya, R., & Jain, V. (2020). COVID-19 and applications of smartphone technology in the current pandemic. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(5), 733–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.033

Kim, D., Lee, Y., Lee, J., Nam, J. K., & Chung, Y. (2014). Development of Korean smartphone addiction proneness scale for youth. PloS One, 9(5), e97920.

Kim, H. J., Min, J. Y., Min, K. B., Lee, T. J., & Yoo, S. (2018). Relationship among family environment, self-control, friendship quality, and adolescents’ smartphone addiction in South Korea: Findings from nationwide data. PloS one, 13(2), e0190896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190896

Kim, S. G., Park, J., Kim, H. T., Pan, Z., Lee, Y., & McIntyre, R. S. (2019). The relationship between smartphone addiction and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity in South Korean adolescents. Annals of general psychiatry, 18(1), 1–8.

Kim, D. J. (2020). A systematic review on the intervention program of smartphone addiction. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial cooperation Society, 21(3), 276–288. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2020.21.3.276

Kim, B., Han, S., Park, E. J., Yoo, H., Suh, S., & Shin, Y. (2021). The relationship between mother’s smartphone addiction and children’s smartphone usage. Psychiatry Investigation, 18(2), 126. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.03

Kim, S. H., Jeong, K. H., & Ryu, J. H. (2022). The effects of parental smartphone addition sub-factors on children’s smartphone addiction. The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 30(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.22924/jhss.30.1.202202.002

Kuss, D., Harkin, L., Kanjo, E., & Billieux, J. (2018). Problematic smartphone use: Investigating contemporary experiences using a convergent design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010142

Lee, C., & Lee, S. J. (2017). Prevalence and predictors of smartphone addiction proneness among Korean adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 77, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.002

Lee, H., Kim, J. W., & Choi, T. Y. (2017). Risk factors for smartphone addiction in Korean adolescents: Smartphone use patterns. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 32(10), 1674–1679. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.10.1674

Liu, X. X. (2021). A systematic review of prevention and intervention strategies for smartphone addiction in students: applicability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 21(2), 3–36. https://doi.org/10.24193/jebp.2021.2.9

Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2015). Short version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale adapted to Spanish and French: Towards a cross-cultural research in problematic mobile phone use. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.013

Matthes, J., Thomas, M. F., Stevic, A., & Schmuck, D. (2021). Fighting over smartphones? Parents’ excessive smartphone use, lack of control over children’s use, and conflict. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106618

Meltzoff, A. N., & Moore, M. K. (1977). Imitation of facial and manual gestures by human neonates. Science, 198, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4312.75

Meltzoff, A. N. (2007). ‘Like me’: a foundation for social cognition. Developmental science, 10(1), 126–134.

Ministry of Science and ICT(MSIT) & National Information Society Agency(NIA). (2022). 2021 Smartphone Overdependence Survey. Retrieve from https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do;jsessionid=32AE282D1232C0D23BBAE173C5EE5C4C.2894582dd32606361891?cbIdx=65914&bcIdx=24288&parentSeq=24288. Accessed 3 Apr 2022

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being (Vol. 2017). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273856-en

Olson, J. A., Sandra, D. A., Colucci, É. S., Al Bikaii, A., Chmoulevitch, D., Nahas, J., ... & Veissière, S. P. (2021). Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries. Computers in Human Behavior 107138

Panova, T., & Carbonell, X. (2018). Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.49

Pereira, F. S., Bevilacqua, G. G., Coimbra, D. R., & Andrade, A. (2020). Impact of problematic smartphone use on mental health of adolescent students: Association with mood, symptoms of depression, and physical activity. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(9), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.49

Putra, A. R., Handayani, B., Darmawan, D., Retnowati, E., Sinambela, E. A., Ernawati, E., ... & Lestari, U. P. (2022). Relationship between parenting parenting and smartphone use for elementary school age children during the Covid 19 pandemic. Bulletin of Multi-Disciplinary Science and Applied Technology, 1(4):138-141

Randler, C., Wolfgang, L., Matt, K., Demirhan, E., Horzum, M. B., & Beşoluk, Ş. (2016). Smartphone addiction proneness in relation to sleep and morningness-eveningness in German adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(3), 465–473.

Reynaud, E., Navarro, J., Lesourd, M., & Osiurak, F. (2019). To watch is to work: A review of neuroimaging data on tool use observation network. Neuropsychology Review, 29(4), 484–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-019-09418-3

Rizzolatti, G., & Sinigaglia, C. (2010). The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: Interpretations and misinterpretations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(4), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2805

Sánchez. E. (2006). What effects do mobile phones have on people’s health? Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network report; http://www.euro.who.int/document/e89486.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2022

Sohn, S. Y., Rees, P., Wildridge, B., Kalk, N. J., & Carter, B. (2019). Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2350-x

Son, H. G., Cho, H. J., & Jeong, K. H. (2021). The effects of Korean parents’ smartphone addiction on Korean children’s smartphone addiction: Moderating effects of children’s gender and age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136685

Song, S. M., Park, B., Kim, J. E., Kim, J. E., & Park, N. S. (2019). Examining the relationship between life satisfaction, smartphone addiction, and maternal parenting behavior: A south Korean example of mothers with infants. Child Indicators Research, 12(4), 1221–1241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9581-0

Ting, C. H., & Chen, Y. Y. (2020). Smartphone addiction. Adolescent Addiction (pp. 215–240). Academic Press.

Twenge, J. M., Haidt, J., Joiner, T. E., & Campbell, W. K. (2020). Underestimating digital media harm. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(4), 346–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1

Wetzel, B., Pryss, R., Baumeister, H., Edler, J. S., Gonçalves, A. S. O., & Cohrdes, C. (2021). “How Come You Don’t Call Me?” Smartphone Communication App Usage as an Indicator of Loneliness and Social Well-Being across the Adult Lifespan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126212

Yu, Z. Y., & Liu, W. (2019). A meta-analysis of relation of smartphone use to anxiety, depression and sleep quality. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 33(12), 938–943. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2019.12.010

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study concept and design were handled by KHJ and SHK. KHJ analyzed the data. SL, SHK, and JHR interpreted the findings and drafted the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors after critical review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This report was exempted from approval by the institutional review boards (IRB) of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Semyung University (IRB number: 2022–04-001). Every participant gave a written consent prior to their participation in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeong, KH., Kim, S., Ryu, J.H. et al. A Longitudinal Relationship Between Mother’s Smartphone Addiction to Child’s Smartphone Addiction. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00957-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00957-0