Abstract

This study examines compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction in two groups of counselors who specialize in substance dependency treatment in order to identify the unique features of substance abuse service delivery that may be related to professional quality of life. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 20 substance abuse counselors working with offenders both in prison and community facilities. In addition, interview subjects completed the ProQOL-IV to assist in exploring the unique challenges that may face the substance abuse treatment field with regards to professional self-care. Two key themes emerged from the examination of the group of interviewees that scored high on the Compassion Fatigue Subscale on the ProQOL-IV, revealing that working with women is more challenging, and substance abuse counselors who have family members with addiction problems or themselves are in recovery may make one more susceptible to compassion fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The National Association of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselors recently announced that the shortage of substance abuse treatment counselors has reached crisis level (NAADAC 2007). While high turnover rates, a lack of new professionals entering the field, and an increased need for substance abuse treatment have been cited as possible reasons for this shortage, studies show that professional quality of life may be compromised by the nature of the work (high levels of job frustration and stress, and exposure to complex, highly distressing cases) (Fahy 2007; Knudsen et al. 2006). For a field with an already higher than average turnover rate (Kaplan 2003), it seems appropriate to further explore the predictors of burnout and compassion fatigue with regards to substance abuse treatment counselors. This study examines compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction in two groups of counselors who specialize in substance dependency treatment in order to identify the unique features of substance abuse service delivery that may be related to professional quality of life.

Literature Review

The emotional investment by the worker and the emotional connection between client and worker is what differentiates burnout from more generalized occupational stress, according to Maslach et al. (1997). A human service worker suffering from burnout may feel helpless and hopeless, chronically tired, and trapped in their job (Sorgaard et al. 2007). These workers may enter the field with idealistic intentions of improving the lives of others or perhaps even being a “savior” or “rescuer”, which they assume will give their own life more meaning. When expectations are too high or are unrealistic, the worker may become disillusioned, disappointed, and burned out.

Burnout is connected to high rates of absenteeism and turnover, which is monetarily draining to organizations that must expend financial resources on recruiting, hiring, and training new staff (Maslach et al. 1997). In addition, during this time of turnover, the remaining staff are left to absorb the absent staff member’s caseload, which may add a heavy burden to already overloaded personnel. Perhaps even more consequential to the organization and their clients is the contagious nature of burnout, which at high levels has been shown to result in reduced patient/client satisfaction and increased treatment drop out (Ducharme et al. 2008).

The available research shows that there are over 100 factors thought to be associated with burnout for substance abuse counselors (Aiken and Sloane 1997). Some studies suggest an individual’s inability to cope with work stressors causes burnout (Cordes and Dougherty 1993; Golembiewski et al. 1998; Rowe 1997), or that an individual’s personality “type” can make them more vulnerable to occupational stress. For example, Moore and Cooper (1996) found that Type A personalities (competitive, very time conscious, ambitious) are more likely to suffer from burnout compared to other personality types.

Some demographic characteristics that have been shown to play a role in one’s susceptibility to burnout include age, with younger counselors more susceptible. While studies on the impact of race and gender have mixed results (Garland 2002; Maslach et al. 2001), Kruger et al. (1991) found that male mental health counselors showed lower levels of emotional exhaustion, while Davis (2008) found that male counselors reported higher levels of burnout. Females tend to discuss work problems and frustrations with coworkers more than males, therefore developing greater social support (Kruger et al. 1991; Stevanovic and Rupert 2004). Women also tend to employ behaviors that may contribute to stress reduction and their improved functioning (Tamres et al. 2002) at a higher rate than men. As for race, one study found that nonwhite respondents had more stress about their future (Prosser et al. 1997), while another determined that whites reported experiencing more on the job stress than nonwhites (Ross et al. 1989).

Counselors with a higher level of educational attainment and those who are unmarried may have increased vulnerability to burnout (Garland 2002; Garner et al. 2007). Some research has found that counselors with more experience suffer less burnout due to the development of effective coping mechanisms (Farber 2000; Farmer et al. 2002; Garland 2004). Yet, other research has suggested that stress actually accumulates over the years for counselors, and the more time they had spent in the field the less they enjoyed working with clients (Pines and Maslach 1978).

The state of an individual’s relationships, both personal and work-related can predict burnout, while supportive relationships at home and work can protect an individual from burnout (Ducharme et al. 2008; Lee and Akhtar 2007; Maslach et al. 1997). A lack of self-care, which is common in workers who are always caring for others, can increase the risk for burnout. However, if an individual has a supportive, reasonably peaceful home life and invests in their own care, they are better prepared to handle stress at work.

The literature is equivocal regarding predictors of occupational stress for counselors who themselves are in recovery from drug and/or alcohol addiction. Rubington (1984) found those counselors in recovery had higher rates of burnout while the findings of Elman and Dowd (1997) were divergent. Counselors in recovery are thought to invest more “emotional labor” in their work by having a stronger identification with their clients, which can lead to greater involvement with clients who may be in denial, unmotivated, and have the potential for relapse which places the counselor at higher risk for burnout (McNulty et al. 2007). Interestingly, Elman and Dowd (1997) suggested that counselors in recovery were less likely to burn out because of the social support they receive through their own recovery process as well as the sense of personal accomplishment they obtain from their continued sobriety.

A commonly cited reason for burnout is a substance abuse counselor’s high caseload (Ducharme et al. 2008). A high caseload is especially exhausting when the counselor has a higher proportion of more difficult clients. Moreover some clients have higher needs for wraparound services, particularly women and those who are of lower socio-economic status (McNulty et al. 2007). Other clients who can be more difficult to treat are those who are court mandated to treatment (Ducharme et al. 2007; McNulty et al. 2007), a common occurrence in the substance use dependence field.

There are also organizational factors that can predict burnout in substance abuse counselors. The most commonly cited factor is the amount of autonomy the counselor feels in their job (Ducharme et al. 2007; Duraisingam et al. 2006; Knudsen et al. 2008). Substance abuse counselors are also more susceptible to burnout if they have unclear role expectations or role conflicts in their work (Elman and Dowd 1997; Gallon et al. 2003; Knudsen et al. 2003). Additionally, if counselors perceive that there is unfairness in management practices; this too can result in burnout (Ducharme et al. 2007; Knudsen et al. 2008).

Counseling with traumatized individuals often involves the client recalling memories of the traumatizing experience in an effort to bring closure to the event. This process exposes the therapist multiple times to the traumatic event through the descriptive narrative provided by the patient, which results in the therapist experiencing indirect exposure to the trauma (Bride et al. 2007; Fahy 2007). This in conjunction with the compassion a therapist typically feels towards their client makes them susceptible to developing compassion fatigue.

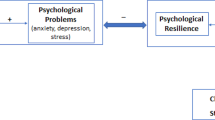

Compassion fatigue and burnout are similar in that they both lead to feelings of anxiety, depression, and helplessness. However, burnout is not trauma-related and is a slow-building process. In contrast, a mere single exposure to the recounting of a trauma narrative can produce compassion fatigue (Figley 1995). Compassion fatigue is considered a more “user friendly” term for Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) whose symptoms mimics Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Figley 1995). The individual afflicted with STS may become hypervigilent, and may have dreams, images, and/or thoughts about the described trauma (Romey 2005). In addition, therapists who suffer from STS or compassion fatigue may experience psychological distress, which can include feeling a sense of burden, avoidance, feelings of horror and fear, cognitive changes, and functional impairment (Figley 2002). This can cause the therapist to avoid working with traumatized clients on issues related to their trauma by ignoring it or redirecting the client’s attention. Another potential consequence of STS and compassion fatigue is emotional detachment by the therapist (Dutton & Rubinstein 1995). This is a protective measure, which may result in a strained therapeutic relationship.

Not all therapists who work with trauma clients develop compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue typically results when a therapist working with a traumatized client is unable to cope with the stress involved with the work and lacks adequate support at work and home (Follette et al. 1994; Radey and Figley 2007). Additionally, some studies show that having a personal history of trauma has been associated with higher rates of compassion fatigue (Allt 1999; Chrestman 1995; Dickes 1998; Kassam-Adams 1994; Nelson-Gardell and Harris 2003; Pearlman and Mac Ian 1995; Price 2001). However, there have also been contradictory studies suggesting personal trauma history is not associated with higher rates of secondary traumatic stress (Creamer and Liddle 2005; Follette et al. 1994; Schauben and Frazier 1995; Simonds 1996). There has also been research that strongly suggests the “amount of exposure” a therapist has working with trauma clients, including the amount of time, proportion of their caseload, and collective exposure percentage, can increase the likelihood of secondary traumatic stress (Baird and Kracen 2006; Brady et al. 1999; Creamer and Liddle 2005; Meyers and Cornille 2002; Simonds 1996; Wee and Myers 2003).

There are several demographic variables that have been studied in relation to the development of secondary traumatic stress. Female therapists appear to experience higher levels of secondary traumatic stress than their male coworkers (Kassam-Adams 1995; Meyers and Cornille 2002; Sprang et al. 2007; Van Hook et al. 2008). Age has also been shown to be a predictor of secondary traumatic stress as younger therapists are considered more at risk for developing symptoms (Arvay and Uhlemann 1996; Munroe 1990). In addition, less experienced counselors appear to be more susceptible to secondary traumatic stress (Hellman et al. 1987). Several studies have found a therapists level of education to be related to their susceptibility to secondary traumatic stress, with those who have less than a master’s degree being at a higher risk (Arvay and Uhlemann 1996; Follette et al. 1994; Pearlman and Mac Ian 1995).

In Figley’s (2002) etiological model of compassion fatigue, empathetic ability and empathetic response are considered requirements for the development of the condition. According to the theory, if a counselor does not have the ability to empathize with their clients, they may be at lower risk for compassion fatigue.

There is little research indicating the rate of compassion fatigue among substance abuse counselors, however two recent studies by Bride (2007) and Bride et al. (2009) have begun to illuminate the condition for counselors. Bride (2007) conducted a survey of master’s level social workers in a southern state and determined that the rate of secondary traumatic stress is twice that of the general population. This study found that 15.2 percent of the respondents had symptoms meeting the criteria for PTSD. In addition, 70 % of respondents had experienced one or more symptoms during the previous week, and over half met the criteria for one or more core symptom clusters. More recently, Bride and colleagues (2009) found in a study examining substance abuse counselors and their trauma training and practices that 19 % of their sample reported STS symptoms that had occurred in the previous seven days, a number more than twice as high as the general population’s lifetime prevalence of PTSD. While these studies shed some light onto the prevalence of those working in the field of social work and substance abuse treatment, there are limitations with these studies (low response rate, narrow samples) that suggest the problem may be larger than what was reported.

For the substance abuse counselor, treating clients with trauma histories and PTSD is common, as 60 to 90 percent of those seeking treatment for substance abuse report being physically and/or sexually abused (Baschnagel et al. 2006; Bride 2007; Cohen and Densen-Gerber 1982; Dansky and Brady 1996). Furthermore, 30 to 50 percent meet the criteria for PTSD diagnosis (Dansky and Brady 1996; Najavits et al. 1997). Substance abusing females have even higher rates of trauma with over half reporting physical abuse and almost three quarters reporting sexual abuse (Covington 2007).

Traumatized clients are found to turn to alcohol or drugs to suppress nightmares and flashbacks (Brown 2000). Furthermore, the substance abuser with PTSD has poorer treatment outcomes, and higher rates of relapse than those without PTSD (Brown 2000; Covington 2007). This means that not only is treating a client for substance abuse who has PTSD more taxing due to their greater needs, both tangible and emotional, but they also typically come with more frustration for the counselor due to their greater risk for relapse. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that substance abuse counselors who treat traumatized populations will be at higher risk for job frustration, burnout, and compassion fatigue.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a qualitative analysis of substance abuse counselor burnout and compassion fatigue considering individual and workplace characteristics. Since the compassion fatigue literature is extremely limited with reference to substance abuse counselors, it was necessary to employ exploratory methods as a “necessary first step in the systematic inquiry of a phenomenon, with the goal of describing what is actually happening and then generating hypotheses for future study” (Werstlein and Borders 1997, p. 122). Exploration of themes from these interviews provides the basis for future quantitative investigations and sheds some light on previous empirical work in the area of compassion fatigue and burnout in helping professionals.

Methods

Qualitative Procedure

A total of 20 face-to-face interviews were conducted with substance abuse counselors across a southern state. In order to select work sites with diverse workplace characteristics, 10 counselors working in state prisons and 10 counselors working in diverse community settings were selected as these are the primary publically funded sites for substance abuse treatment and represent the venues where most services are delivered. Twenty interviews were identified as the saturation point for this investigation when data themes began to converge. Contact was made via professional referral for the first interview in each workplace setting, from there, snowball sampling was utilized to recruit the remainder of the interviewees. Eligible participants for this study were substance abuse counselors working in a publicly funded substance abuse treatment center or program with at least 50 percent of their caseload reporting a history of trauma exposure.

Since the sample is relatively small, the number of referrals was limited to four per facility. This helped to insure counselors with a variety of backgrounds and views were examined from several different facilities, including three prisons, one jail, and three community treatment facilities. Care was taken to select several locations for recruitment with varying characteristics. The prison counselors were recruited from three prisons and one jail. The prisons varied as to security level, the clientele, and substance abuse program type. One of the prisons offered a modified therapeutic community program, while the other two had what were called “inpatient treatment programs.” The three prison substance abuse programs lasted for approximately six to eight months in duration. All three prisons were medium or minimum security, and two were male prisons while the third housed female inmates. The jail substance abuse program was less structured relative to the prison programs, and included assessment, treatment, and a reintegration programming. All three of the prison programs and the jail program utilized individual and group counseling.

To recruit the community substance abuse counselors, three diverse substance abuse treatment facilities were approached. All three facilities were inpatient residential and two of them also had an outpatient component. One program served all male clientele, another served only women, and the third program was co-ed. Two of the three were located in small urban areas, while one, a halfway house, was located in a more rural setting. All three programs indicated that a majority, if not all, of their clients were currently involved in the criminal justice system.

The interviews took place in the participants work location. All participants were given an opportunity to have the interview conducted at a non-work location to enhance privacy, however, each individual declined. Every interview began with a description of the research project, and an explanation of the informed consent process. Each participant received a one-time payment of $30 for their time. Permission to audio record the interviews was sought at the beginning of each interview, however five participants declined recording, in which case only handwritten notes were taken.

At the conclusion of the interviews, extensive notes relating to the recently completed interview and the participant as well as their work location were written. These notes assisted in recreating the interview more vividly during the analysis stage, as well as provided detailed information about the physical environment in which the counselor worked. Each taped interview was also personally transcribed, and those that were not recorded were typed as soon as possible following the conclusion of the interview. Each participant was assigned a pseudonym to protect their identity, and other identifying information, such as work location, were masked. All protocols were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Interview Measures

Participant interviews lasted approximately 45–60 min. The questions were divided into four sections, including basic demographic questions, questions about how participants view themselves and their work as substance abuse counselors, questions related to compassion fatigue and burnout, and also questions related to social support. Interview questions were developed specifically for this study, and were developed based on the current literature available. At the conclusion of the interview, each interviewee completed both the ProQOL-IV Scale and the General Empathy Scale.

The Professional Quality of Life Scale

Each participant completed a Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL R-IV), which includes three subscales: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Compassion Fatigue (Stamm 2002). Each subscale includes 10 items describing the respondents experiences on a Likert-type scale, which the respondent indicates how frequently they have experienced that item in the past 30 days, ranging from “never” to “very often” (0 to five). The ProQOL is the most commonly used scale for determining a helper’s quality of life, and has been cited in over 200 published papers (Stamm 2009). The alpha reliability scores for the scale are: Compassion Satisfaction = .88; Burnout = .75; and Trauma/Compassion Fatigue = .81.

Stamm (2009) reports that the average score on each scale is 50 with a standard deviation of 10. According to Stamm (2009, p. 17), “about 25 % of people score above 57 and about 25 % of people score below 43” on each scale. If an individual scores above 57 on either the Burnout or the Trauma/Compassion Fatigue Scale, it is suggested they examine what might be causing them to either feel ineffective in their work or why they are “frightened,” depending on which scale they scored high on (Stamm 2009).

The General Empathy Scale

Participants were asked to complete the General Empathy Scale (Caruso and Mayer 1998), which includes items describing varying feelings and emotions in certain situations on a Likert-type Scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (one to five). The General Empathy Scale includes six subscales related to empathy: suffering, positive sharing, crying, emotional attention, feel for others, and emotional contagion. The alpha reliability for this scale is .88.

Analysis

A six step approach was utilized for data analysis (Creswell 2009; Tesch 1991, Marshall and Rossman 2006). The first step was to organize the data, including typing up summary interview notes, and the transcription of the interviews. The second step required immersion in the data, which included reading all of the data collected to gain an overall sense of the data, and to record emerging ideas. The transcripts and typed notes were read multiple times in a variety of sequences to allow for comparison of individuals in particular categories (i.e. workplace, gender). The reading and rereading of the transcripts allowed for immersion in the data and led to the development of themes, such as the commonality of participants whom had family members who were in recovery. The third step was to code all of the data into categories. The fourth step included reviewing the coding and to generate themes to include in the data analysis. The fifth step was to describe the themes that emerged from the data using narrative passages. And the sixth step was to interpret the findings. MAXQDA software was utilized to assist the researcher in data organization, data coding, and conducting the data analysis for emerging themes. Since the compassion fatigue literature is extremely limited with reference to substance abuse counselors, it was necessary to employ a method that would allow for both deductive and inductive reasoning. Allowing for exploratory methods are a “necessary first step in the systematic inquiry of a phenomenon, with the goal of describing what is actually happening and then generating hypotheses for future study” (Werstlein and Borders 1997, p. 122).

Coding of data began with a review of participant responses guided by the research question. This generated the initial list of codes, which was then added to as additional codes emerged from the data. To test the coding scheme and insure reliability, a second reader coded two of the transcripts (approximately 10 %), which showed 100 % agreement between the readers. The MAXQDA software was used to support the coding process. This program allowed for the creation of codes and sub-codes based on the interview responses.

Interview Sample Demographic Characteristics

Interview participants ranged in age from 26 to 52. The mean and median ages were 37 and 38 respectively. Twelve participants were female and eight were male. Two of the counselors were in recovery from substance dependence. Twelve of the twenty participants were married or in a long-term domestic relationship, the remaining eight were either divorced or single. Nine of the participants had earned a Master’s Degree, and five participants were Certified Drug and Alcohol Counselors (CDAC). The sample was almost entirely comprised of Non-Hispanic Whites (18 of 20), which fairly accurately reflects the population of the state in which interviews were conducted according to the most recent census data (88.9 % White; http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/21000.html).

Six counselors came into substance abuse counseling after working with Child Protective Services, four prison counselors either worked their way up the ranks after starting as correctional officers or came after spending time working for probation and parole, while four community counselors began their career in substance abuse counseling immediately after they completed their college degrees. Two counselors were previously working in general mental health counselor positions and then moved into substance abuse counseling. The two counselors in recovery embarked on their careers after beginning their own journey into recovery and wanting to assist others. And two counselors took the job because “they were who was hiring.”

Results

Qualitative Results

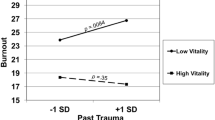

As Table 1 indicates, five out of the twenty substance abuse counselors interviewed scored high on the Compassion Satisfaction Subscale, and three scored low on the scale. Three counselors scored high on the Burnout Subscale, while one counselor scored low on this scale. And nine counselors scored high on the Compassion Fatigue Subscale, while three scored low. Two themes emerged from the data analysis while comparing counselors who had scored high on the ProQOL-IV Compassion Fatigue Subscale: 1) working with women is challenging, and 2) having a family member with an addiction problem/or being in recovery makes one more susceptible to compassion fatigue.

Working with Women is Challenging

Out of the nine counselors who scored high for Compassion Fatigue, three of them (one-third) worked in women’s facilities (one in a women’s prison, the other two in a women’s facility in the community), and three others worked in a co-ed facility in the community. Interviews with counselors working with females indicated special considerations for working with this particular clientele. Nadine and Jacinda, female counselors working in a community treatment facility for women, spoke of their need to protect against over-identification with their clients, and having to measure their responses to their client’s traumatic stories:

After awhile it becomes easier to take, hearing the stories...... You have to keep yourself in check to not feel like “I have heard worse”. Nadine

I do struggle sometimes with the realness of the situation, and try to let them know that it is not okay what they went through. That helps me frame things for them. Jacinda

Janet, a counselor working in a women’s community treatment facility spoke of the importance of her work with women, and the important implications for the children involved:

I find it empowering to help other women to help themselves. It can be frustrating and disappointing, but the benefit when you succeed is long term sobriety within families.

However, Becky, a female counselor working in a women’s prison spoke of the difficulty in working with women, and not necessarily difficulties related to hearing their trauma stories:

A caseload of 24 women is more than 100 men. They are backstabbing and bitchy.

Becky spoke of her job including a lot of “detective work” with regards to her clients and their behaviors. She also painted a picture of an “us against them” mentality, which was not seen in other facilities. Becky also scored high for Burnout, and low for Compassion Satisfaction and Empathy. Interestingly, her co-worker Dave scored in the moderate range for Compassion Satisfaction and Burnout, and low for Trauma/Compassion Fatigue and Empathy. Dave echoed Becky’s tone and sentiment to great extent, but did not seem to be as affected by the work as Becky, presumably due to his low level of empathy.

I compare it to factory work, you do what you are supposed to do with the pieces coming to you… The job is stressful, but it is not rocket science. Dave, male counselor working in a female prison

Personal/Familial History Increases Risk of Compassion Fatigue

Another key theme from the interviews was that the risk for developing compassion fatigue may be increased if the service provider has personal experiences with addiction. Five of the nine counselors who scored “high” for Compassion Fatigue on the ProQOL Scale-IV (three in a prison, the other two in community facilities) spoke about having a family member who had also battled addiction problems, and one who was in recovery himself.

I have family members with domestic violence and addiction problems and have been pulled into the fallout from that. It makes me more open to their capacity to change. Also, it touches a place in me that is more vulnerable. I have to be aware of what I need. Phyllis, female counselor working in a co-ed community facility

Another interesting finding was that out of the five counselors having a family member who had also battled addiction problems or were in recovery, three of them also scored high on the Compassion Satisfaction Subscale of the ProQOL-IV. This is especially of note considering only four counselors total (out of 20) scored high for Compassion Satisfaction. Therefore, these counselors are having feelings of professional fulfillment and personal satisfaction from their work, while also feeling the more negative effects of the emotional drain of their work. For these counselors it appeared as though their recovery status or having a loved one battling substance dependence had become their master status. One’s master status is the characteristic an individual identifies with the most, is at the core of their social identity and is the status they would be most likely to identify themselves with above all other characteristics (Brown 1991). Master status also affects an individual’s behavior in every aspect of their life, not just those directly related to that status. In the case of these counselors, they did not view substance abuse counseling as a job or as a career, it even seemed to go beyond a “calling”, instead, it appeared to shape the way they approached most aspects of their lives.

Organizational Characteristics

All of the counselors interviewed reported that they felt supported by both their co-workers and supervisors. There were variations on the amount of support felt however, and community-based counselors were less likely than prison-based counselors to approach their supervisors for assistance when they felt overwhelmed by their work. These counselors who were overwhelmed and would not approach their supervisors were more likely to score high on the Compassion Fatigue Subscale on the ProQOL-IV. Out of the six counselors who indicated they did not ask their supervisor for assistance, four of them scored high on the Compassion Fatigue Subscale of the ProQOL-IV. In addition, almost half of the counselors interviewed who scored high on the Compassion Fatigue Subscale of the ProQOL-IV stated they felt overwhelmed by their work but would not ask their supervisor for help.

While this research hoped to determine if there were differences between workplace location regarding levels of burnout and compassion fatigue, there appeared to be no difference between the levels of burnout and compassion fatigue in counselors working in a prison versus those working in the community based on the qualitative comments, and the scores on the ProQol (see Table 1).

Discussion

The present study investigated occupational stress in substance abuse counselors working in a variety of settings, and explored the unique challenges that may face the substance abuse treatment field with regards to professional self-care. Two key themes emerged from the qualitative interviews that may shed some light on the substance abuse counselor’s professional quality of life. Examination of the group of interveiwees that scored high on the Compassion Fatigue Subscale on the ProQOL-IV revealed that working with women is more challenging, and substance abuse counselors who have family members with addiction problems or themselves are in recovery may make one more susceptible to compassion fatigue.

There could be a number of reasons for this finding. First, while historically there have been fewer women abusing alcohol and drugs than men, those women who abuse substances typically face more difficulty in obtaining treatment then men do (Beckman 1994). Women usually have fewer financial resources to pay for treatment and also typically have childcare issues which may preclude them from seeking treatment (Robinson 2006). In addition, there is a “familial circle of denial” (Kaufman 1992) where a female is more likely to hide her substance use from her family and reciprocally her family ignores her behaviors. This is in part due to sex role stereotyping which sees the female substance abuser as a social deviate (McCaul and Furst 1994).

Since women are not seeking treatment at the rates of their male counterparts, when they do enter treatment they may be further along in the disease cycle. In fact, in studies comparing male and female patterns of alcohol and heroin use, Almog et al. (1993) found that women have a more rapid dependence than males, and a more rapid escalation of consumption levels than their male counterparts. The “telescoping” course of alcohol dependence in women is established in the empirical literature, and illustrates the importance of early prevention, and detection for women (Mann et al. 2005). Additionally, women report higher rates of marital and family discord, an increase in psychiatric illness, higher rates of depression, more health-related problems, and higher incidences of both physical and sexual abuse (Cook et al. 2005; Menicucci and Wermuth 1989) than male substance users. These factors can dictate increased time investment from the counselor, higher need for wraparound services, and a greater emotional investment for those providing care for female substance abusers (Taxman et al. 2007). It appears the substance abuse treatment community would benefit from a greater understanding of the difficulties in treating women for substance abuse. Both Bride (2001) and Copeland et al. (1993) found that merely having a single gender substance abuse treatment environment does not increase treatment retention and completion. Instead, Bloom and Covington (2008) suggest a need for gender-responsive treatment for female substance abusers. Woman-centered treatment suggests in addition to taking into consideration the many domains of a woman’s life, utilizing individualized treatment, women only groups, having a warm, child-friendly environment, addressing past trauma issues, and focusing on empowerment (Bloom and Covington 2008). The counselor to client gender match should also be considered, since over-identification and shared history may be precursors to adverse outcomes for the client and the professional.

Similarly, there is a hole in the literature in describing the experiences of substance abuse counselors who have a family member with addiction and trauma exposure. While there is some literature surrounding the substance abuse counselor in recovery (see Culbreth and Borders 1999; Hecksher 2007), it has never been addressed with regards to compassion fatigue, which recovering counselors and those with family members in recovery are at risk for developing. More needs to be understood about the dynamic of these counselors relating to their clientele, and what can be done to protect them from suffering from compassion fatigue. It reasons that much could be learned from counselors in this position.

Limitations

As with all qualitative research, these results are exploratory and should not be generalized to other populations or settings. Furthermore, not all of the interviews were tape recorded due to a lack of permission by several of the participants. During qualitative interviews, tape recording allows the interviewer to capture not only every word spoken, but the tone as well. Note taking may have interfered with the interviewer’s ability to develop rapport with the interview participant, and therefore could have curtailed the information provided by the respondent. Finally, even though all of the interviews were conducted at the participants’ workplace, behind a closed door, it is possible that the interview participants may not have been completely truthful if they had concerns of being overheard. However, the respondents were informed about the nature of the questions, and allowed to select the location of the interview.

Conclusions

Substance abuse treatment facilities should act proactively to enhance the emotional well-being of their staff by providing a range of prevention and intervention services for their workers, keeping in mind that those who are most troubled may be those with shared history, and who may be working with women. Organizational strategies such as wellness promotion, strategic case assignment (to achieve a balance of trauma and non-trauma cases), and informal opportunities to debrief have been shown to be effective strategies (Sprang et al. 2011).

References

Aiken, L. H., & Sloane, D. M. (1997). Effects of organizational innovations in AIDS care on burnout among urban hospital nurses. Work and Occupations, 24(4), 453–477.

Allt, J. (1999). Vicarious trauma: A survey of clinical and counseling psychologists. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Surrey, England.

Almog, Y., Anglin, M., & Fisher, D. (1993). Alcohol and heroin use patterns of narcotics addicts: gender and ethnic differences. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 19(2), 219–238.

Arvay, M. J., & Uhlemann, M. R. (1996). Counsellor stress in the field of trauma: a preliminary study. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 30(3), 193–210.

Baird, K., & Kracen, A. C. (2006). Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: a research synthesis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 181–188.

Baschnagel, J., Coffey, S., & Rash, C. (2006). The treatment of co-occurring PTSD and substance abuse disorders using trauma-focused exposure therapy. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 2(4), 498–508.

Beckman, L. (1994). Barriers to alcoholism treatment for women. Alcohol Health and Research World, 18(3), 208–209.

Bloom, B. E., & Covington, S. S. (2008). Addressing the mental health needs of women offenders. In R. Gido & L. Dalley (Eds.), Women’s mental health issues across the criminal justice system. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Brady, J. L., Guy, J. D., Poelstra, P. L., & Brokaw, B. F. (1999). Vicarious traumatization, spirituality, and the treatment of sexual abuse survivors: a national study of women psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30(4), 386–393.

Bride, B. (2001). Single-gender treatment of substance abuse: effect on treatment retention and completion. Social Work Research, 25(4), 223.

Bride, B. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52(1), 63–70.

Bride, B. E., Radey, M., & Figley, C. R. (2007). Measuring compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35, 155–163.

Bride, B. E., Hatcher, S. S., & Humble, M. N. (2009). Trauma training, trauma practices, and secondary traumatic stress among substance abuse counselors. Traumatology, 15(2), 96–105.

Brown, J. D. (1991). The professional ex-: an alternative for exiting a deviant career. The Sociological Quarterly, 32(2), 219–230.

Brown, P. J. (2000). Outcome in female patients with both substance use and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 18(3), 127–135.

Caruso, D. R., & Mayer, J. D. (1998). A measure of emotional empathy for adolescents and adults. Unpublished Manuscript.

Cohen, F. S., & Densen-Gerber, J. (1982). A study of the relationship between child abuse and drug addiction in 178 patients: preliminary results. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect, 6(4), 383–387.

Cook, L., Epperson, L., & Gariti, P. (2005). Determining the need for gender-specific chemical dependence treatment: assessment of treatment variables. The American Journal on Addictions, 14(4), 328–338.

Copeland, J., Hall, W., Didcott, P., & Biggs, V. (1993). A comparison of a specialist women’s alcohol and other drug treatment service with two traditional mixed-sex services: client characteristics and treatment outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 32(1), 81–92.

Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 621–656.

Chrestman, K. R. (1995). Secondary exposure to trauma and self-reported distress among therapists. In B. H. Stamm (Ed.), Secondary traumatic stress: Self care issues for clinicians, researchers, and educators (pp. 29–36). Lutherville: Sidran Press.

Covington, S. (2007). Working with substance abusing mothers: a trauma-informed, gender-responsive approach. Source, 16(1), 1–11.

Creamer, T. L., & Liddle, B. J. (2005). Secondary traumatic stress among disaster mental health workers responding to the September 11 attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(1), 89–96.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Culbreth, J. R., & Borders, L. D. (1999). Perceptions of the supervisory relationship: recovering and nonrecovering substance abuse counselors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77(3), 330–338.

Dansky, B. S., & Brady, K. T. (1996). Victimization and PTSD in individuals with substance use disorders: gender and racial differences. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 22(1), 75–93.

Davis, D. (2008). The ethics of self-care: Burnout among substance abuse professionals. Dissertation Abstracts International, 69(1-B). (UMI No.3296727).

Dickes, S. J. (1998). Treating sexually abused children versus adults: An exploration of secondary traumatic stress and vicarious traumatization among therapists. Dissertation Abstracts International, 62(03). (UMI No. 3009821).

Ducharme, L. J., Mello, H. L., Roman, P. M., Knudsen, H. K., & Johnson, A. J. (2007). Service delivery in substance abuse treatment: reexamining “comprehensive” care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 34(2), 121–136.

Ducharme, L. J., Knudsen, H. K., & Roman, P. M. (2008). Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: the protective role of coworker support. Sociological Spectrum, 28(1), 81–104.

Duraisingam, V., Pidd, K., Roche, A., & O’Connor, J. (2006). Satisfaction, stress & retention among alcohol and other drug workers in Australia. Adelaide: National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction.

Dutton, M. A., & Rubinstein, F. L. (1995). Working with people with post traumatic stress disorder: Research implications. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 82–100). New York: Brunner-Mazel.

Elman, B. D., & Dowd, E. T. (1997). Correlates of burnout in inpatient substance abuse treatment therapists. Journal of Addictions and Offender Counseling, 17(2), 56–65.

Fahy, A. (2007). The unbearable fatigue of compassion: notes from a substance abuse counselor who dreams of working at Starbuck’s. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35, 199–205.

Farber, B. A. (2000). Introduction: understanding and treating burnout in a changing culture. JCLP/In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice, 56(5), 589–595.

Farmer, R., Clancy, C., Oyefeso, A., & Rassool, G. H. (2002). Stress and work with substance misusers: the development and cross-validation of a new instrument to measure staff stress. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 9(4), 377–388.

Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. Journal of Clinical Psychology/In Session, 58, 1433–1441.

Follette, V. M., Polusny, M. M., & Milbeck, K. (1994). Mental health and law enforcement professionals: trauma history, psychological symptoms, and impact of providing services to child sexual abuse survivors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25(3), 275–282.

Gallon, S. L., Gabriel, R. M., & Knudsen, R. W. (2003). The toughest job you’ll ever love: a Pacific Northwest treatment workforce study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 24, 183–196.

Garland, B. (2002). Prison treatment staff burnout: consequences, causes, and prevention. Corrections Today, 64(7), 116–121.

Garland, B. (2004). The impact of administrative support on prison treatment staff burnout: An exploratory study. The Prison Journal, 84(4), 452–471.

Garner, B. R., Knight, K., & Simpson, D. D. (2007). Burnout among corrections-based drug treatment staff: impact of individual and organizational factors. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 51(5), 510–522.

Golembiewski, R., Boudreau, R., Sun, B., & Luo, H. (1998). Estimates of burnout in public agencies: worldwide, how many employees have which degrees of burnout, and with what consequences? Public Administration Review, 58(1), 59–66.

Hecksher, D. (2007). Former substance users working as counselors: a dual relationship. Substance Use & Misuse, 42, 1253–1268.

Hellman, I. D., Morrison, T. L., & Abramowitz, S. I. (1987). Therapist experience and the stresses of psychotherapeutic work. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, and practice, 24(2), 171–177.

Kassam-Adams, N. (1995). The risks of treating sexual trauma: Stress and secondary trauma in psychotherapists. The Sidran Press.

Kaplan, L. (2003, November). Substance abuse treatment workforce environmental scan. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration.

Kassam-Adams, N. (1994). The risks of treating sexual trauma: Stress and secondary trauma in psychotherapists. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia, 1994). Dissertation Abstracts International, 55, 4606.

Kaufman, E. (1992). Countertransference and other mutually interactive aspects of psychotherapy with substance abusers. The American Journal on Addictions, 1(3), 185–202.

Knudsen, H., Johnson, J., & Roman, P. (2003). Retaining counseling staff at substance abuse treatment centers: effects of management practices. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 24, 129–135.

Knudsen, H. K., Ducharme, L. J., & Roman, P. M. (2006). Counselor emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in therapeutic communities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31, 173–180.

Knudsen, H. K., Ducharme, L. J., & Roman, P. M. (2008). Clinical supervision, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention: a study of substance abuse treatment counselors in the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35, 387–395.

Kruger, L. J., Botman, H. I., & Goodenow, C. (1991). An investigation of social support and burnout among residential counselors. Child and Youth Care Forum, 20(5), 335–352.

Lee, J. S., & Akhtar, S. (2007). Job burnout among nurses in Hong Kong: implications for human resource practices and interventions. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 45(1), 63–84.

Mann, K., Ackermann, K., Croissant, B., Mundle, G., Nakovics, H., & Diehl, A. (2005). Neuroimaging of gender differences in alcohol dependence: are women more vulnerable? Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(5), 896–901.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (2006). Designing qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S., & Leiter, M. (1997). Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422.

McCaul, M., & Furst, J. (1994). Alcoholism treatment in the United States. Alcohol Health and Research World, 18(4), 253.

McNulty, T. L., Oser, C. B., Johnson, J. A., Knudsen, H. K., & Roman, P. M. (2007). Counselor turnover in substance abuse treatment centers: an organizational-level analysis. Sociological Inquiry, 77(2), 166–193.

Menicucci, L., & Wermuth, L. (1989). Expanding the family systems approach: cultural class, developmental and gender influences in drug abuse. American Journal of Family Therapy, 17(2), 129–142.

Meyers, T. W., & Cornille, T. A. (2002). The trauma of working with traumatized children. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 39–55). New York: Brunner Routledge.

Moore, K. A., & Cooper, C. L. (1996). Stress in mental health professionals: a theoretical overview. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 42(2), 82–89.

Munroe, J. F. (1990). Therapist traumatization from exposure to clients with combat related post-traumatic stress disorder: Implications for administration and supervisors. Dissertation Abstracts International, 52(03). (UMI No 9119344).

Najavits, L. M., Weiss, R. D., & Shaw, S. R. (1997). The link between substance abuse and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in women: a research review. The American Journal on Addictions, 6(4), 273–283.

National Association of Alcohol and Drug Addictions Counselors (NAADAC) (2007). Issue brief: Current and future addiction workforce. Retrieved December 14, 2008, from http://naadac.org/documents/display.php?documentID=98. Results from the 2010.

Nelson-Gardell, D., & Harris, D. (2003). Childhood abuse history, secondary traumatic stress, and child welfare workers. Child Welfare League of America, 82(1), 5–26.

Pearlman, L. A., & Mac Ian, P. S. (1995). Vicarious traumatization: an empirical study of the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26(6), 558–565.

Pines, A., & Maslach, C. (1978). Characteristics of staff burnout in mental health settings. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 29(4), 233–237.

Price, M. (2001). Secondary traumatization: Vulnerability factors for mental health professionals. Unpublished doctoral dissertation: University of Texas.

Prosser, D., Johnson, S., Kuipers, E., Szmukler, G., Bebbington, P., & Thornicroft, G. (1997). Perceived sources of work stress and satisfaction among hospital and community mental health staff, and their relation to mental health, job burnout, and job satisfaction. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 43(1), 51–59.

Radey, M., & Figley, C. R. (2007). The social psychology of compassion. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35, 207–214.

Robinson, R. (2006). Health perceptions and health-related quality of life of substance abusers: a review of the literature. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 17(3), 159–165.

Romey, W. D. (2005, June). Loyalty: A key concept to understand therapists’ symptoms of compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma. Unpublished manuscript.

Ross, R. R., Altmaier, E. M., & Russell, D. W. (1989). Job stress, social support, and burnout among counseling center staff. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(4), 464–470.

Rowe, M. (1997). Hardiness, stress, temperament, coping, and burnout in health professionals. American Journal of Health Behavior, 21, 163–171.

Rubington, E. (1984). Staff burnout in a detox center: an exploratory study. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 1, 61–71.

Schauben, L. J., & Frazier, P. A. (1995). Vicarious trauma: the effects on female counselors of working with sexual violence survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 49–64.

Simonds, S. L. (1996). Vicarious traumatization in therapists treating adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Dissertation Abstracts International, 57(08). (UMI No. 9702738).

Sorgaard, K. W., Ryan, P., Hill, R., & Dawson, I. (2007). Sources of stress and burnout in acute psychiatric care: inpatient versus community staff. Social Psychiatry and Pyschiatric Epidemiology, 42, 794–802.

Sprang, G., Clark, J. J., & Whitt-Woosley, A. (2007). Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout: factors impacting a professional’s quality of life. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 12, 259–280.

Sprang, G., Craig. C., & Clark, J. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in child welfare workers: a comparative analysis of occupational distress across professional groups. Child Welfare 90(6), 149–168.

Stamm, B. H. (2002). Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Test. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 107–122). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Stamm, B. H. (2009). The ProQOL Manual. Retrieved March 5, 2010 from www.proqol.org.

Stevanovic, P., & Rupert, P. (2004). Career-sustaining behaviors, satisfactions, and stresses of professional psychologists. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41(3), 301–309.

Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D., & Helgeson, V. S. (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: a meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 2–30.

Taxman, F. S., Young, D. W., & Fletcher, B. W. (2007). The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices survey: an overview of the special issue. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(3), 221–223.

Tesch, R. (1991). Software for qualitative researchers: Analysis needs and program capabilities. In: Using computers in qualitative research (pp. 16–37). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Van Hook, M. P., Rothenberg, M., Fisher, K., Elias, A., Helton, S., Williams, S. et al. (2008, February). Quality of life and compassion satisfaction/fatigue and burnout in child welfare workers: A study of the child welfare workers in community based care organizations in central Florida. Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of North American Association of Christians in Social Work (NACSW), Orlando, Florida.

Wee, D., & Myers, D. (2003). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and critical incident stress management. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 5(1), 33–37.

Werstlein, P., & Borders, L. (1997). Group process variables in group supervision. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 22(2), 120–136.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perkins, E.B., Sprang, G. Results from the Pro-QOL-IV for Substance Abuse Counselors Working with Offenders. Int J Ment Health Addiction 11, 199–213 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9412-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9412-3