Abstract

Vitality is an understudied protective mechanism within the psychotherapy literature. This study explored the impact of vitality on the relationship between a counselor’s past traumatic experiences on their compassion fatigue. The sample consisted of 113 licensed counselors from a variety of disciplines (e.g., social workers, professional counselors, and marriage and family therapists) and represented an international sample. Findings showed that vitality is significant as a protective mechanism for the development of compassion fatigue for counselors with a history of trauma. The ego depletion hypothesis is provided as a context to describe this relationship and the role vitality plays. Implications for the practicing clinician are provided within this context.

Similar content being viewed by others

The professional life of a mental health counselor is not routine, linear, nor consistent. The array of clients a counselor encounters across their career is vast, with clients bringing forth a variety of experiences (Knight 2015; Lawson 2007; Rosenberg and Pace 2006) and emotions (Hensel et al. 2015; Thompson et al. 2014). While clinicians often bring hope, energy, empathy, and life to the individuals and families they work with (Skovholt 2012), counselors frequently experience exhaustion and emotional depletion through their interactions with clients (Sadler-Gerhardt and Stevenson 2012; Figley 2002). Over time, this work with clients takes a toll on the vitality (i.e., the energy available to oneself; Ryan and Deci 2008), rigor, and effectiveness of the therapeutic work (McKim and Smith-Adcock 2014; Craig and Sprang 2010; Figley 1995, 2002). The exhaustion and emotional depletion counselors may experience can also impact their self-esteem and self-perceptions (Lawson et al. 2007). These personal and therapeutic difficulties are likely to lead to the development of compassion fatigue.

Compassion fatigue is a consequence of caring for others and is a form of caregiver burnout from encountering the consistent suffering of others (Figley 2002). Compassion fatigue contrasts with typical burnout because of the associated feelings of helplessness and confusion, compounded with a greater sense of isolation from supports (Figley 2002). While research has found inconsistencies in the symptomology of therapists and the impact their past has on current symptoms (Adams et al. 2001; Dunkley and Whelan 2006), more recent investigations suggest that counselors’ past trauma does affect current wellbeing and clinical work (Hensel et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2012). Clinicians with a history of trauma may be at an increased risk for compassion fatigue (Hensel et al. 2015). Figley and Figley (2017) more recently developed a model of compassion fatigue resilience and found that there are a variety of protective factors that may prevent or alleviate compassion fatigue. Vitality is the positive feeling of being alive and energetic (Ryan and Frederick 1997) and has been noted as a fundamental mechanism to cope with life’s challenges (Rozanski 2005). Given that counselors with traumatic pasts may gravitate towards the helping profession, they must possess an inner strength, or resilience, pushing and motivating them toward their continued professional pursuit. A sense of energy, or vitality, may be the catalyst for this continued motivation towards professional practice and a potential mechanism to decrease the negative impact of clinical work. Within the compassion fatigue resilience model (Figley and Figley 2017), subjective vitality is therefore assumed to be positively associated with a sense of satisfaction and self-care while manifesting in practice as empathic ability and a sense of perceived autonomy (Deci and Ryan 1987).

Vitality is a subjective experience based on one’s understanding of the self as autonomous, competent, and engaged (Ryan and Deci 2008). Vitality as a subjective state, is a source of energy a counselor feels (Ryan and Deci 2008). To be a mental health clinician, one must summon up the energy to be focused while engaging with clients on a recurrent basis. A counselor must also be able to maintain energy throughout the session to be mindful, present, and regulated. Ultimately, perceived subjective vitality reflects individual’s well-being (Ryan and Frederick 1997; Ryan et al. 2010). It is the feeling of being really “alive,” and the opposite of feeling drained.

Research tends to focus on negative effects that affect human behaviors; however, the field of positive psychology has prompted a resiliency-based examination of psychological processes (Seligman 2008). Using a strengths-based approach, vitality is a mechanism that may contribute, in part, to counselors’ ability to continue providing focus, attention and empathy to difficult cases, and, may serve as a protective factor against a counselor’s susceptibility to compassion fatigue. To date, little scholarship, has focused on these buffering effects of vitality between a counselor’s experiences with personal trauma and their perceived compassion fatigue. Such research may help stem-the-tide and allow clinicians who have a history of trauma to work more effectively with and for the clients they serve. Therefore, the purpose of this study, is to investigate vitality as a protective mechanism to the relationship between a counselor’s history of trauma and compassion fatigue.

Literature Review

The Influence of Trauma on Compassion Fatigue

We are all a product of our history. Past experiences impact future wellness in many ways (Elliott and Guy 1993; Thomason and Marusak 2017). With counselors, it is through experiences with clients, that the past can be brought to the surface when triggered in therapy sessions through transference and counter-transference (Sharpless and Barber 2015). Counselors battle with internal struggles that may be exacerbated when they work with people with trauma (Ghahramanlou and Brodbeck 2000; Pearlman and Mac Ian 1995; Thompson et al. 2014; VanDeusen and Way 2006). These internal struggles may reflect past emotions and feelings as a result of a counselor’s personal experiences dealing with similar stressors or experiences. Working with clients with a similar past can further intensify emotions and feelings within the counselor (Follette et al. 1994). This counter-transference experience of the clinician’s trauma projected on to the client’s experiences can impact the therapeutic and clinical work; potentially creating withdrawal, boundary issues, and other vulnerabilities in the therapeutic process (Canfield 2005). Specifically, emotional boundary issues may develop, where a counselor may not know when their emotions and feelings are their own, an over identification with the client’s experience and related emotions, and, as a result, the counselor may struggle with distinguishing their emotions from their client’s emotions (Zepf and Hartmann 2008). Counselors carrying their own afflictions may find it difficult to differentiate between being empathetically engaged and experiencing countertransference. This line may easily be crossed. It is through this dichotomy of counter-transference and empathetic engagement that compassion fatigue may emerge.

Clinicians bring their experiences with them to sessions (Figley 1995). It is not uncommon for a counselor’s interest in this profession to derive from past experiences and many therapists may gravitate towards the field of social services due to traumatic experiences from their past (Esaki and Larkin 2013). These traumatic experiences can lead clinicians to work with a specific population because of their own history. Interacting with clients that trigger personal experiences further prompt counter-transference in the therapeutic relationship (Dunkley and Whelan 2006; Hensel et al. 2015; Nelson-Gardell and Harris 2003), potentially compounding the counselor’s emotions and feelings related to the client experiences (Valent 2002). Interest in helping others, focused empathy, and intense compassion may trigger a counselor to become compassion fatigued (Figley and Figley 2017).

Perceived Subjective Vitality and Compassion Fatigue

Ancient Native American teachers revealed to their healers that, “each time you heal someone, you give away a piece of yourself, until, at some point, you will require healing” (Stebnicki 2007, p. 317). Counselors are healers. During a therapy session, clinicians provide safety, connection, empathy, reflection, non-judgement, all of which are imperative for the healing process. These healing abilities take energy. Vitality then, is the energy summoned by counselors, despite the presence of negative emotions and experiences, to continue to do therapeutic work with clients. Vitality is both a process and a product (Ryan et al. 2010), meaning that vitality can be developed and is the result of intentional investment. Perceived vitality in one’s daily functioning is related to wellbeing, self-esteem and satisfaction of life (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Likewise, vitality can also be a result of being mindful (Brown and Ryan 2004; Canby et al. 2015; Grossman et al. 2004). Subjective vitality is shown to relate to one’s sense of agency, self-actualization and personal well-being, and is an indicator of a person’s health of spirit (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Additionally, vitality is related to motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic (Nix et al. 1999), and this may have an impact on one’s experiences of being either drained, depleted, or conversely, feeling alive or having vitality.

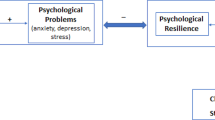

Perceived subjective vitality can be considered the antithesis of compassion fatigue, or a compassion fatigue resilience mechanism. Vitality is energy sustained, rather than compassion fatigue being the depletion of caring energy. Ryan and Frederick (1997) described vitality as a specific psychological experience of possessing enthusiasm and spirit. Vitality, as a subjective self-construal, may also be related to a perspective shift. In many cases, moods are more important than events in determining perspective, and one’s mood determines whether they may enjoy a particular event, or not (Thayer 2001). Mood systems reflect vitality, which reflects one’s physical and psychological wellbeing (Thayer 2001). Therefore, vitality is a mechanism by which a counselor may begin to establish and utilize coping skills. The opposite may also be true. If a sense of one’s vitality and energy are deficient, coping through life and work stressors may be extra challenging. This relationship between vitality and compassion fatigue, and the impact of the absence of vitality, could potentially further predispose a counselor towards compassion fatigue.

People vary in their subjective experience of vitality as a consequence of life situations, either physical influences (illness and exhaustion) and psychological factors (being complimented, finding a partner), and because of this, fluctuations in energy are common, not only as a component of general illness, but also as an aspect of psychological wellbeing (Ryan and Frederick 1997). To our knowledge, there has been an absence of research that has explored perceived subjective vitality with mental health clinicians, so understanding the function of such self-perceptions as it relates to a mental health counselor’s experience with personal trauma and compassion fatigue is needed.

Compassion Fatigue

The concept of compassion fatigue was introduced in the literature to explicitly address the struggle and strain of caregiving on the caregiver (Figley 1995, 2002). Although the term compassion fatigue was not fully defined at the time, it has now been studied as it relates to a variety of helping professions, specifically mental health counselors (Figley 2002; Thompson et al. 2014). Compassion fatigue describes the fatigue of the empathic and compassionate work that encompasses being a counselor. In the systems literature compassion fatigue and its related concepts have been referred to as systemic traumatic stress (Goff and Smith 2005), implying the relational aspect to catching the trauma. The symptoms of compassion fatigue parallel many of the symptoms of PTSD, such as anxiety, depression, withdrawal, avoidance, exhaustion, preoccupation with trauma, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts (Bride et al. 2007; Figley 2002). Compassion fatigue can include experiencing the client’s traumatic event and thus avoidance of reminders of the client and their traumatic event (Figley 2002). Therefore, compassion fatigue is a byproduct of the journey therapists experience as they walk along the path of suffering with their clients. Compassion fatigue is described as the combination of burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Figley 2002; Stamm 2002, 2010). Figley and Figley (2017) stress that compassion fatigue originates as a self-monitoring deficit in clinician’s interactions with clients. This lack of self-monitoring results in a build up of secondary traumatic stress that is moderated by clinician’s memories of past trauma, their accumulative exposure to other’s suffering, as well as their own unanticipated exposures to direct sources of stress.

Literature in this field has shed light on the occurrence of mental health counselors manifesting compassion fatigue symptoms (Figley 1995; Canfield 2005; Devilly et al. 2009; Craig and Sprang 2010). The extant research has explored a variety of factors that may be further impacting a clinician’s experience with compassion fatigue such as engaging in self-care practices (Venart et al. 2007; Thompson et al. 2014), the impact of workplace environments, including coworker supports (Knudsen et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2014) and supervisor supports (Knudsen et al. 2013). Additionally, length of time engaging in practice as a counselor has been found to impact compassion fatigue, with younger therapists reporting higher burnout than more seasoned counselors (Craig and Sprang 2010). Given the probability and prevalence of compassion fatigue among clinical professionals, counselors also need to be aware of their own personal histories of trauma and how these histories may compound the effects of compassion fatigue (Williams et al. 2012). More recently, Figley and Figley (2017) have proposed a compassion fatigue resilience model (CFRM) to understand the risk factors associated with compassion fatigue as well as the protective factors for compassion resilience. According to their model, a counselor that has higher compassion fatigue resilience is more likely to endure the suffering of clients. Subsequently, we propose that perceived subjective vitality may operate as a compassion fatigue resilience mechanism in counselor’s interactions with clients.

The Moderating Role of Perceived Subjective Vitality

Within the work environment, there are a variety of stressors and demands that impact feelings and functioning, and thus, one’s vitality. Counselors experience burnout further with the demands of therapeutic work, which include long periods of inactivity, paperwork, large caseloads, and their perceived autonomy in their work and practice (Lent and Schwartz 2012; Thompson et al. 2014). Researchers have remarked on the importance of vitality in understanding motivation and wellness (Nix et al. 1999; Ryan and Frederick 1997; Rozanski 2005). Previous studies have found that vitality may be an important protective factor towards wellness (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Though vitality has not been explored directly with counselors, studies show that there is a positive relationship between vitality and self-esteem, self-actualization and personal wellbeing (Ryan and Frederick 1997; Van Dierendonck 2004). Vitality then is an important variable to consider with counselors due to the paradoxical experiences of why some counselors are able to sustain in their profession, and not succumb to compassion fatigue, and why other counselors are not. Vitality is a potentially important variable to explore that may impact counselors’ susceptibility to compassion fatigue, especially among those with a traumatic past.

Limited research has placed emphasis on protective mechanisms, such as vitality, that could offset the relationship between trauma and compassion fatigue. Vitality is complex and requires further exploration to understand more fully its impact on counselors and their compassion fatigue. One hypothesis that may describe the importance of vitality and its impact on compassion fatigue is the ego depletion hypothesis (Baumeister et al. 1998). Derived from Freud’s work on the psychic energy available to the self, Freud explored energy within his patients and described that a patient’s energy was drained by conflicts and repression (Freud 1923; Ryan and Deci 2008). Ryan and Deci (2008) further described that the ego depletion hypothesis suggests that self-regulation is a muscle, and that regulation requires work to modulate emotions and feelings. Baumeister et al. (1998) argued that humans have a limited ability for choices. Self-regulation and self-control require energy and regulation of behavior requires energy that is depleted by this effort. We may have desires for certain acts or decisions; however, we are not able to act on everything we wish. They posit that constant engagement in self-regulation and self-control, are depleting and result in ego depletion (Baumeister et al. 1998).

Applying this model to counselors provides a rationale and possible explanation for why counselors with a past history of trauma may encounter increased susceptibility for compassion fatigue. Counselors engage with clients in an intimate setting. This intimate setting requires that the counselor is vulnerable with their emotions in order to engage in empathetic attunement with the client. It is through this empathetic attunement that emotions and feelings on the part of the counselor, described as counter-transference, may arise. Counselors must be in constant attunement with themselves to regulate their own emotions and feelings, differentiating them from the client’s emotions and feelings. Counselors engaging in constant regulation of the mind and body in therapy sessions, checking in with themselves, moment-by-moment, modulating and suppressing feelings, may be entangled in the energy depletion behavior, increasing susceptibility to compassion fatigue.

The purpose of the present study is to investigate whether vitality moderates the relationship between a clinician’s trauma history and compassion fatigue, both burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Though there are a variety of defenses (i.e., physical activity, journaling, family support, personal counseling, among others) counselors possess that may be impactful in decreasing compassion fatigue, this study examines the role of vitality as a protective factor for counselors with a history of personal trauma and the impact on compassion fatigue.

The Current Study

This study examined the impact of vitality on a counselor’s experience of compassion fatigue. Additionally, counselor’s vitality was examined as a moderator between a counselor’s personal history of trauma and their experience of compassion fatigue. Based on review of the literature, we hypothesized that:

H1

Trauma would positively impact compassion fatigue (burnout and secondary traumatic stress)

H2

Vitality would show a negative relationship with compassion fatigue (burnout and secondary traumatic stress)

H3

Vitality would moderate the relationship between past and recent trauma and compassion fatigue (burnout and secondary traumatic stress)

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through email with a link to an online survey. Local and national professional association listservs were utilized to elicit participation (e.g., American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy [AAMFT], National Counsel of Family Relations [NCFR], and the American Counseling Association [ACA]). In the recruitment email we requested that recipients forward the email to others that may be interested in participating. Upon interest in participating, in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) ethics committee standards, participants were provided informed consent and acknowledged their consent before participating in the online survey.

The sample consisted of 113 counselors, with the majority of therapists living within the United States (91%) and the remaining 9% living outside of the United States (e.g., Italy, Beirut, United Arab Emirates, France, India, Iran, New Zealand, Brazil). Participants were predominately female (77%), their ages ranging between 24 and 76 years of age (Mage=44.06, SD= 13.83), and the majority identifying as non-Hispanic white (69%), with the next largest demographic group identifying as Hispanic/Latina(o) (16%). Several licensures were represented in the sample, with licensed Marriage and Family Therapists representing nearly half of the sample (47%). Almost half of the counselors (40%) reported that they are in private practice. Counselors reported an average of 11.15 years of practice experience, they worked 35.81 h per work week on average, and had an average a caseload of 17.06 clients. Descriptive statistics, associated alpha levels (Cronbach’s α), and a correlation matrix of main analytic variables are found in Table 1.

Procedure

Using an online survey format, subjects took a 140-question survey. We utilized online survey data with prior studies comparing online survey formats to written survey formats having shown minimal differences in participants’ responses to questions (Beck et al. 2014). Moreover, some have reported that responses on more sensitive questions, such as trauma, observe less social desirability bias (Wang et al. 2005). Participants were asked to respond to questions assessing professional quality of life, attention and awareness, vitality, past experiences and well-being. This study focused specifically on past experiences, vitality and professional quality of life.

Measures

Childhood Trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Pennebaker and Susman 2013) was used to assess for therapist’s history of traumatic experiences. This questionnaire uses two measures, with a total of 13 main questions. The first measure is a past traumatic events scale (i.e., a traumatic experience before the age of 17) which includes 6 questions about past traumatic events. Participants reported an average of 2.11 (SD= 1.53) traumatic experiences before the age of 17. The second measure is a recent traumatic events scale (i.e., a traumatic experience within the last 3 years) and included 7 questions about recent traumatic events. Participants reported an average of 1.87 (SD= 1.20) traumatic experiences within the past 3 years. Example questions include: prior to the age of 17, did you have a traumatic sexual experience (raped, molested, etc.)? and Within the past 3 years, did you have a traumatic sexual experience (raped, molested, etc.)? Questions yielded a yes or no response.

Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL)

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (Stamm 2010) was used to measure compassion fatigue (burnout and secondary traumatic stress). The original measure includes 30 questions that assessed burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction. Only the burnout and secondary traumatic stress subscales were used. Questions from this scale are presented on a 5-point-likert-scale, from never (1) to very often (5). The burnout subscale included 10 questions (sample item: “I feel overwhelmed because my caseload seems endless”). These ten items were summed to reflect higher composite scores of burnout (Cronbach’s α = .79). Counselors in this study reported an average score of 21.35 (SD = 5.29) for burnout. The secondary traumatic stress subscale utilized 10 questions (sample item: “I find it difficult to separate my personal life from my life as a helper”). These ten items were summed to reflect higher composite scores of secondary traumatic stress (Cronbach’s α = .81). Therapists reported an average score of 21.57 (SD= 5.32) for secondary traumatic stress. The psychometric properties of the Professional Quality of Life Scale have been widely researched and have shown both high internal consistency and convergent validity (Stamm 2010).

Subjective Vitality Scale (VS)

The Subjective Vitality Scale was used to assess counselors’ subjective feelings of being alive and energetic (Ryan and Frederick 1997). One cannot directly measure energy available to the self, so vitality is explored as a subjective variable. This 7-item scale assesses clinicians state of feeling energy using a six-point Likert scale, from not at all true (1) to always true (5) (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Studies have shown this scale to be psychometrically sound (Cronbach’s α = .84) (Bostic et al. 2000; Ryan and Frederick 1997). Subjective vitality scores have shown good psychometric properties including internal consistency and convergent validity (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Responses were summed to reflect high composite scores of subjective vitality (Cronbach’s α = .89). Counselors in this study reported an average vitality score of 4.35 (SD= 1.29).

Data Analysis Strategy

Preliminary Data Analysis

Prior to conducting the main analyses, preliminary analyses were conducted to assess for outliers and missing data using SPSS v.23.0. The missing was less than 5% for any item, and there were no evident patterns in the missing data observed. We addressed the missing data by using a chained imputation approach (Allison 2002). Following this, descriptive statistics, alpha level reliabilities (Cronbach α) and a bivariate correlation matrix were examined (see Table 1). Based on the designed parameter ranges for variance inflation factor (VIF ≤ 10) and tolerance (> 0.2) (Field 2013), there were no observed issues of multicollinearity and univariate skew and kurtosis were within normal distribution ranges.

Main Analytic Procedures

Main analytic procedures were carried out using SPSS v. 23.0. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to assess the direct influence of past and recent trauma on compassion fatigue, both burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Potential controls such as gender, age, and years in practice were assessed due to previous findings having shown these variables as significant covariates with main analytic variables (Craig and Sprang 2010; Killian 2008; Thomas and Otis 2010). Significant relationships were not found with the main analytic variables. Therefore, these were not retained as controls for subsequent analyses.

The first multiple linear regression analyses (see Table 2) assessed the direct influence of past and recent trauma with burnout (Block 1). Block 2 then incorporated the moderating effect of vitality on past and recent trauma on burnout. Significant interaction effects were plotted using Preacher’s online utility (Preacher et al. 2006). The second multiple linear regression analyses (see Table 3) assessed the direct influence of past and recent trauma on secondary traumatic stress (Block 1). Block 2 incorporated the moderating effect of vitality on past and recent trauma on secondary traumatic stress. Again, significant interaction effects were plotted using Preacher’s online utility (Preacher et al. 2006).

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables used in these analyses are reported in Table 1. Before conducting hypothesis testing, descriptive statistics were computed on measures of traumatic events, vitality, and compassion fatigue—both burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Correlations were observed between recent and past trauma, as well as between burnout and vitality (all correlations were at p < .01).

Main Analyses

Separate block analyses were conducted for both past and recent trauma on compassion fatigue, both burnout and secondary traumatic stress, when moderated by vitality. Our first goal was to examine the direct effects of past trauma on burnout, moderated by vitality. Standardized beta weights are presented. Results indicate that past trauma did not have an effect on burnout (β = .07, p = .29); however, vitality negatively predicted burnout (β = − .70, p < .001). In Block 2, past trauma continued to have no effect on burnout, with vitality holding constant (β = − .70, p < .001). The interaction term of vitality moderating past trauma was added in Block 2 as well (see Table 2). Results show significant moderation was present (β = − .17, p < .001) (see Fig. 1), meaning that vitality buffers the effect of past trauma on levels of burnout.

Next, the effects of both recent trauma and vitality were examined on burnout. Results indicated that while recent trauma had no effect on burnout (β = .001, p = .98), vitality had a significant effect (β = − .69, p < .001). In Block 2, recent trauma continued to have no effect on burnout, with vitality holding constant (β = − .73, p < .001); however, vitality was found to moderate and reduce the effect of recent trauma on burnout (β = − .18, p = .01). See Fig. 2 for moderating effects. These results indicate that these counselors experiencing vitality were less likely to experience burnout, even in the presence of past/recent trauma.

Similarly, separate block analyses were conducted for the impact of past and recent trauma on secondary traumatic stress when moderated by vitality (see Table 3). Results indicate that past trauma has no effect on secondary traumatic stress; however, vitality negatively predicted secondary traumatic stress (β = − .34, p < .001). In block 2, past trauma continued to have no effect on secondary traumatic stress, with vitality holding constant (β = − .34, p < .001); however, vitality was found to moderate and reduce the effect of past trauma on secondary traumatic stress (β = − .24, p = .006). See Fig. 3 for moderating effects. These results provide some evidence that counselors with vitality were less likely to experience secondary traumatic stress, even in the presence of past trauma.

Next, the effects of both recent trauma and vitality were examined on secondary traumatic stress. Results show that while recent trauma had no effect on secondary traumatic stress, vitality had a significant effect (β = − .33, p < .001). In Block 2, recent trauma continued to have no effect on secondary traumatic stress, with vitality holding constant (β = − .36, p < .001). There were no moderating effects.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between counselors’ history of trauma, the impact that trauma has on their compassion fatigue, and how subjective vitality may play an important preventative role. As expected, results supported the hypothesis that perceived subjective vitality would operate as a moderator for the relationship between trauma and compassion fatigue; specifically, vitality showed a significant interaction effect on the relationship between past and recent trauma and burnout, and past trauma and secondary traumatic stress. Subjective vitality also played an important role in attenuating the likelihood that prior trauma will eventually lead to a clinician’s experience of compassion fatigue. These results corroborate with the existing literature on vitality as a factor that promotes positive outcomes (e.g., Allen and Kiburz 2012; Ryan and Frederick 1997). While our findings did not show a direct relationship between trauma and either aspect of compassion fatigue, this study did show that vitality affected compassion fatigue, and more importantly, moderated the effect between trauma and burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Hence, findings from this investigation contribute to the growing literature on compassion fatigue and adds the possible impact perceived subjective vitality may play as an important mechanism to further explore and understand how it relates to clinicians’ development of compassion fatigue resilience.

With family therapists representing close to half of the sample in this study, it is important to understand vitality within a systems lens. Bowens concept of differentiation (Bowen 1978) provides a context to understand vitality. Differentiation of self is the ability to balance separateness and togetherness (Bowen 1978) and the ability to do this can greatly impact psychological wellness (Bowen 1978; Skowron et al. 2009). Family clinicians emphasize the treatment of families which means that oftentimes there is more than one client within the session, the family is the client. Working with more than one person in the session may increase feelings of burnout for the clinician (Rosenberg and Pace 2006). Additionally, the family is an emotional system (Bowen 1976) and the complexity of providing family therapy may take an extra toll on the vitality of a family clinician if not attuned to; thus, the system in which the clinician works within can impact perceived vitality (i.e., burnout contagion; Bakker et al. 2001). The counselor can be impacted emotionally by the multiple family members in the room and the counselor’s energy can impact their clients in session as well (Shamoon et al. 2017). Considering clinician vitality within a systems lens requires further exploration.

Limitations and Future Research

The design of the current study limits our ability to fully understand the relationship between trauma and compassion fatigue and the impact of vitality; whereas a longitudinal design would allow for a clearer understanding of how subjective vitality operates as a resiliency factor in preventing compassion fatigue. Therefore, the research and implications should be considered with the following limitations in mind.

The modest sample size and the demographics suggests limitations in generalizability of findings. For example, a large proportion of the counselors (41%) disclosed being in private practice, whereas the remaining 59% worked at an agency. Differing environmental contexts may have impacted experiences with vitality and compassion fatigue. Another limitation for this study is that most of the participants were women (77%), 69% of the overall sample identified as White, and nearly half were family counselors. With these limitations in mind, studies should focus on incorporating a larger and more diverse sample of clinicians. Future research should also intentionally explore vitality for both individual and family clinicians.

Another limitation is the trauma questionnaire asked about traumatic experiences through retrospective self-report assessment and did not include the evaluative component of the questionnaire to allow the clinician to describe their subjective construal of the impact of the disclosed traumatic event. The trauma questionnaire we utilized addressed major and significant traumas and did not address chronic trauma or less significant traumas occurring over time. It is possible that chronic trauma or events not disclosed through use of this questionnaire may influence a counselor’s development as well, therefore the conclusions drawn are specific to the traumatic experiences measured by the questionnaire only.

Likewise, a further limitation with the traumatic events questionnaire is that this study did not assess for specific daily lifestyle stressors that have been noted previously as variables impacting compassion fatigue such as: family supports, family dynamics, work-related supports, specific financial stressors, income levels, specialized training, age and years of experience, or other forms of social support (Sprang et al. 2007; Killian 2008; Craig and Sprang 2010). Future research should explore a variety of compounding variables that affect stress to further understand the relationship between trauma and its impact on compassion fatigue.

Finally, this study explored perceived subjective vitality, which is thus impacted by the therapist’s subjective experience and not by objective observations. Previous research has yet to explore therapists’ subjective vitality and its place with practicing mental health clinicians. Future research should explore ways that clinicians can engage in self-care strategies that can enhance their feelings of vitality, creating opportunities for establishing energy sustaining behaviors and to assist in further understanding what creates a vital therapist would be important.

Implications for Practice

This study was prompted by the curiosity surrounding counselor’s compassion fatigue and the potential protective mechanisms curtailing the relationship between a counselor’s personal trauma history and the degree to which they experience compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is pervasive in the helping professions, and thus, understanding protective factors for therapists further pushes our understanding of therapist resilience and strength.

Nix et al. (1999) argue that perceived vitality is related to motivation and that motivation may have an impact on one’s experience of being either drained, depleted or on the other hand, feeling a sense of vitality. Nix et al. (1999) explored these factors and results suggested that engaging in autonomous or self-regulated activities maintained or enhanced subjective vitality. As this article suggests, understanding the mechanisms of restorative environments is imperative in better understanding vitality (Nix et al. 1999). Therefore, subjective vitality and its relationship to compassion fatigue should be understood within the context of the clinician’s environment and the degree to which they feel they have control within their environment, and thus, motivation. Counseling agencies can apply this to the workplace environment of counselors by finding ways for clinicians to have autonomy in their environment. Agencies can think about ways to create spaces for structured freedom and flexibility. Additionally, agency supervision may include engaging clinician’s emotionality through use of Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) interventions aimed at understanding clinician’s emotional experiences and the impact this has on their subjective vitality (Soloski and Deitz 2016).

Using the ego depletion model as the context (Ryan and Frederick 1997), subjective vitality is impacted by repression. Within the therapy setting, counselors may experience repression and suppression, consistently regulating emotions due to counter-transference within the session. Past traumatic experiences may prompt further thought suppression and regulation within the counselor (Ryan and Frederick 1997). The more one is free from conflict and repression, the more access they have to their energy source. Therefore, therapists should be mindful of the impact consistent back-to-back sessions can have on their feelings of vitality due to the nature of the need for suppression of thoughts and emotions. In order to work towards feelings of vitality, implementing a self-care practice that incorporates feelings of autonomy and freedom of expression would be beneficial. This form of self-care can include art, personal therapy, and journaling, using a specific method called the expressive writing paradigm developed by Pennebaker (2004). Expressive writing, writing about emotional upheavals and related thoughts and feelings have been explored as a process for wellbeing (Pennebaker and Chung 2011) and can be a catalyst for expression for counselors experiencing compassion fatigue. Additionally, supervisor use of the Satir model for self-of-the-therapist development is one model to be considered in supervision to process hidden unresolved issues with developing clinicians or clinicians experiencing compassion fatigue (Lum 2002). This model promotes heightened awareness and can provide useful tools to further train and supervise clinicians (Lum 2002). Overall, counselors should be encouraged to process countertransference and any related thought suppression or suppression of emotions with a supervisor or colleague in order to limit the internalization of thoughts and feelings.

As a final implication, family counselors should be attuned to the additive impact that perceived subjective vitality and self-care practices play in building compassion fatigue resiliency. This critical form of resiliency, when maintained, enhances their capacity to empower families (Rappaport 1981) through strength-based, enabling, family focused and systems-oriented practices (Dunst et al. 1988). Frequent sessions with more than one person may increase the susceptibility of compassion fatigue and impact the therapeutic process (see Dunst et al. 1988; Shamoon et al. 2017 for employing strategies that may decrease fatigue susceptibility as well as decrease decay of therapeutic efficacy).

Conclusion

Limited research has explored vitality in the counseling literature. This study was intended to begin to fill the gap and begin a conversation about the role vitality plays as a protective factor to clinicians, specifically those with a personal history of trauma. Findings suggest that vitality is significant in moderating a clinicians’ experience with compassion fatigue overall; and, is worth continued exploration in future research with clinicians, and more specifically with family clinicians. Understanding the mechanisms of restorative environments is imperative in better understanding vitality (Nix et al. 1999). This study may be pointing to a very important role subjective vitality plays in attenuating a clinician’s susceptibility to compassion fatigue while enhancing their practice of career sustaining behaviors.

References

Adams, K. B., Matto, H., & Harrington, D. (2001). The Traumatic Stress Institute Belief Scale as a measure of vicarious trauma in a national sample of clinical social workers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 82, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.178.

Allen, T. D., & Kiburz, K. M. (2012). Trait mindfulness and work–family balance among working parents: The mediating effects of vitality and sleep quality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.09.002.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Sixma, H. J., & Bosveld, W. (2001). Burnout contagion among practitioners. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20, 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.20.1.82.22251.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252–1265.

Beck, F., Guignard, R., & Legleye, S. (2014). Does computer survey technology improve reports on alcohol and illicit drug use in the general population? A comparison between two surveys with different data collection modes in France. PLoS ONE, 9, e85810. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085810.

Bostic, T. J., Rubio, D. M., & Hood, M. (2000). A validation of the subjective vitality scale using structural equation modeling. Social Indicators Research, 52, 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007136110218.

Bowen, M. (1976). Theory in the practice of psychotherapy. In P. J. Guerin (Ed.), Family therapy: Theory and practice (pp. 42–90). New York: Gardner Press.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family treatment in clinical practice. New York: Jason Aronson.

Bride, B. E., Radey, M., & Figley, C. R. (2007). Measuring compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0091-7.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Perils and promise in defining and measuring mindfulness: Observations from experience. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph078.

Canby, N. K., Cameron, I. M., Calhoun, A. T., & Buchanan, G. M. (2015). A brief mindfulness intervention for healthy college students and its effects on psychological distress, self-control, meta-mood, and subjective vitality. Mindfulness, 6, 1071–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0356-5.

Canfield, J. (2005). Secondary traumatization, burnout, and vicarious traumatization: A review of the literature as it relates to therapists who treat trauma. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 75, 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1300/J497v75n02_06.

Craig, C. D., & Sprang, G. (2010). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout in a national sample of trauma treatment therapists. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 23, 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800903085818.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024.

Devilly, G. J., Wright, R., & Varker, T. (2009). Vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress or simply burnout? Effect of trauma therapy on mental health professionals. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670902721079.

Dunkley, J., & Whelan, T. A. (2006). Vicarious traumatization in telephone counsellors: Internal and external influences. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 34, 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880600942574.

Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Deal, A. G. (1988). Enabling and empowering families: Principles and guidelines for practice. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books.

Elliott, D. M., & Guy, J. D. (1993). Mental health professionals versus non-mental-health professionals: Childhood trauma and adult functioning. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24, 83–90.

Esaki, N., & Larkin, H. (2013). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among child service providers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 94, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.4257.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 1–20). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. Psychotherapy in Practice, 58, 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090.

Figley, C. R., & Figley, K. R. (2017). Compassion fatigue resilience. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simons-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 387–398). New York: Oxford University Press.

Follette, V. M., Polusny, M. M., & Milbeck, K. (1994). Mental health and law enforcement professionals: Trauma history, psychological symptoms, and impact of providing services to child sexual abuse survivors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25, 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.25.3.275.

Freud, S. (1923). The Ego and the Id. New York: W.W. Norton.

Ghahramanlou, M., & Brodbeck, C. (2000). Predictors of secondary trauma in sexual assault trauma counselors. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 2, 229–240.

Goff, B. S. N., & Smith, D. B. (2005). Systemic traumatic stress: The couple adaptation to traumatic stress model. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01552.x.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7.

Hensel, J. M., Ruiz, C., Finney, C., & Dewa, C. S. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21998.

Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608319083.

Knight, C. (2015). Trauma-informed social work practice: Practice considerations and challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0481-6.

Knudsen, H. K., Ducharme, L. J., & Roman, P. M. (2008). Clinical supervision, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention: A study of substance abuse treatment counselors in the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35, 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.02.003.

Knudsen, H. K., Roman, P. M., & Abraham, A. J. (2013). Quality of clinical supervision and counselor emotional exhaustion: The potential mediating roles of organizational and occupational commitment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44, 528–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.003.

Lawson, G. (2007). Counselor wellness and impairment: A national survey. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling Education and Development, 46, 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00023.x.

Lawson, G., Venart, E., Hazler, R. J., & Kottler, J. A. (2007). Toward a culture of counselor wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 46, 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00022.x.

Lent, J., & Schwartz, R. (2012). The impact of work setting, demographic characteristics, and personality factors related to burnout among professional counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34, 355–372. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.34.4.e3k8u2k552515166.

Lum, W. (2002). The use of self of the therapist. Contemporary Family Therapy, 24, 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014385908625.

McKim, L. L., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2014). Trauma counsellors’ quality of life. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-013-9190-z.

Nelson-Gardell, D., & Harris, D. (2003). Childhood abuse history, secondary traumatic stress, and child welfare workers. Child Welfare, 82, 5–26.

Nix, G. A., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 266–284. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1999.1382.

Pearlman, L. A., & Mac Ian, P. S. (1995). Vicarious traumatization: An empirical study of the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26, 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.26.6.558.

Pennebaker, J. W. (2004). Theories, therapies, and taxpayers: On the complexities of the expressive writing paradigm. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 138–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph063.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Chung, C. K. (2011). Expressive writing: Connections to physical and mental health. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 417–437). New York: Oxford University Press.

Pennebaker, J. W. & Susman, J. R. (2013). Childhood trauma questionnaire. Measurement instrument database for social science. Retrieved on March 26, 2016 from www.midss.ie.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bouer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986031004437.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8646-7_8.

Rosenberg, T., & Pace, M. (2006). Burnout among mental health professionals: Special considerations for the marriage and family therapist. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 32, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2006.tb01590.x.

Rozanski, A. (2005). Integrating psychologic approaches into the behavioral management of cardiac patients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, S67–S73. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000164252.07368.81.

Ryan, R. M., Bernstein, J. H., & Brown, K. W. (2010). Weekends, work, and well-being: Psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.95.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). From ego depletion to vitality: Theory and findings concerning the facilitation of energy available to the self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 702–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00098.x.

Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65, 529–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x.

Sadler-Gerhardt, C. J., & Stevenson, D. L. (2012). When it all hits the fan: Helping counselors build resilience and avoid burnout. Ideas and Research You Can Use: VISTAS, 2012(1), 1–8.

Seligman, M. E. (2008). Positive health. Applied Psychology, 57, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00351.x.

Shamoon, Z. A., Lappan, S., & Blow, A. J. (2017). Managing anxiety: A therapist common factor. Contemporary Family Therapy, 39, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-016-9399-1.

Sharpless, B. A., & Barber, J. P. (2015). Transference/Countertransference. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp293.

Skovholt, T. M. (2012). The counselor’s resilient self. Turkish Psychological Counseling & Guidance Journal, 4, 137–146.

Skowron, E. A., Stanley, K. L., & Shapiro, M. D. (2009). A longitudinal perspective on differentiation of self, interpersonal and psychological well-being in young adulthood. Contemporary Family Therapy, 31, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-008-9075-1.

Soloski, K. L., & Deitz, S. L. (2016). Managing emotional responses in therapy: An adapted EFT supervision approach. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38, 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-016-9392-8.

Sprang, G., Clark, J. J., & Whitt-Woosley, A. (2007). Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout: Factors impacting a professional’s quality of life. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 12, 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020701238093.

Stamm, B. H. (2002). Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the compassion satisfaction and fatigue test. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Psychosocial stress series, no. 24. Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 107–119). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Stamm, B.H. (2010). The ProQOL concise manual (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.proqol.org/ProQOl_Test_Manuals.html.

Stebnicki, M. A. (2007). Empathy fatigue: Healing the mind, body, and spirit of professional counselors. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 10, 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487760701680570.

Thayer, R. E. (2001). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomas, J. T., & Otis, M. D. (2010). Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: Mindfulness, empathy, and emotional separation. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 1, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.5243/jsswr.2010.7.

Thomason, M. E., & Marusak, H. A. (2017). Toward understanding the impact of trauma on the early developing human brain. Neuroscience, 342, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.022.

Thompson, I., Amatea, E., & Thompson, E. (2014). Personal and contextual predictors of mental health counselors’ compassion fatigue and burnout. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36, 58–77. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.1.p61m73373m4617r3.

Valent, P. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment of helper stresses, traumas, and illnesses. In C. Figley (Ed.), Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 17–37). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Van Dierendonck, D. (2004). The construct validity of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 629–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00122-3.

VanDeusen, K. M., & Way, I. (2006). Vicarious trauma: An exploratory study of the impact of providing sexual abuse treatment on clinicians’ trust and intimacy. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 15, 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v15n01_04.

Venart, E., Vassos, S., & Pitcher-Heft, H. (2007). What individual counselors can do to sustain wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 46, 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00025.x.

Wang, Y.-C., Lee, C.-M., Lew-Ting, C.-Y., Hsiao, C. K., Chen, D.-R., & Chen, W. J. (2005). Survey of substance use among high school students in Taipei: Web-based questionnaire versus paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.017.

Williams, A., Helm, H., & Clemens, E. (2012). The effect of childhood trauma, personal wellness, supervisory working alliance, and organizational factors on vicarious traumatization. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34, 133–153. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.34.2.j3l62k872325h583.

Zepf, S., & Hartmann, S. (2008). Some thoughts on empathy and countertransference. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 56, 741–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065108322460.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical approval

This study received University of New Mexico IRB approval (reference number 18116) before conducting the research.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was provided to each of the participants before they engaged in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin-Cuellar, A., Lardier, D.T., Atencio, D.J. et al. Vitality as a Moderator of Clinician History of Trauma and Compassion Fatigue. Contemp Fam Ther 41, 408–419 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-019-09508-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-019-09508-7