Abstract

A growing number of schools have recently been changing their culture of teaching and learning towards personalized learning. Our study investigates how schools use digital technology to facilitate and promote personalized practices. Based on the answers of a student questionnaire from 31 lower-secondary schools with a personalized learning policy in Switzerland, we selected the three cases with the most frequent use of digital technology in the classroom. Using key categories of digital technology implementation to frame the analysis, we examined the differences and similarities regarding the contribution of digital technology to fostering personalized learning. A systematization of our analyses resulted in three different types in terms of how schools integrate digital tools into their daily practices: 1. selective use of digital technology according to individual teacher preference; 2. selective use of digital technology according to individual student preference; and 3. structural use of digital technology in accordance with a school-wide strategy. The findings provide indications for future research and practice with respect to an implementation of personalized learning that takes full advantage of digital technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

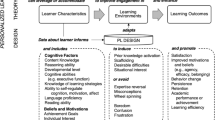

Personalized learning as a student-centered approach to education has aroused growing interest in the educational system because it raises the hope of finding a better way of coping with the students’ heterogeneity at school. Private initiatives and initiatives at national level in mainly Anglo-American countries encourage schools to change their teaching towards personalized learning (e.g., Miliband, 2006; Pane et al., 2017; Waldrip et al., 2014). These initiatives and international research literature picture personalized learning as a multilayered construct that has been defined and implemented in various ways (Keefe, 2007; Zhang et al., 2020a). Despite this conceptual variety, many definitions consider digital technology to be crucial to implement personalized learning (Bingham et al., 2018; ESSA, 2015; Walkington & Bernacki, 2020). Research on the use of digital technology in the area of personalized learning has predominantly examined technological innovations as an enabler of personalized learning environments (Gierl et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2018; McLoughlin & Lee, 2010). For example, one study developed and investigated a mobile adaptive learning system to enable personalized learning on mobile devices (Nedungadi & Raman, 2012). Other studies examined the use of an interactive e-book or media wiki to create a personalized learning environment (Huang et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2014). However, many schools have implemented a form of personalized learning as a whole-school approach and using different technological tools to tailor teaching and learning to the individual needs of students and to increase student choice, especially in Europe (Petko et al., 2017; Schmid & Petko, 2019). At the same time, it is largely unexplored how these schools use digital technology to facilitate and promote their school-wide approach of personalized learning (Bingham et al., 2018; Schmid & Petko, 2019; Zhang et al., 2020a). Therefore, empirical research on how digital technology is generally used in schools with an explicitly personalized learning approach is needed but still limited. Our paper addresses this desideratum and pursues the question how digital technology is used in schools with a school-wide approach to personalized learning. For this purpose, we specifically focus on two dimensions that we consider crucial in defining the concept of personalized learning: student-centered teaching methods and students’ voice and choice. Student-centered teaching methods put the student with her or his individual needs in the center so that he or she can achieve an optimal learning progress. The implementation of student-centered teaching methods includes higher degrees of student self-direction compared to traditional teacher-centered instruction. Due to this active role of the learner, the student receives a say in the content, time, place, and social form of learning, which also gives him or her more responsibility in the learning process. In order to grant students’ voice and choice, a certain degree of student-centered teaching methods is needed. While student-centered teaching methods and students’ voice and choice seem to be two sides of the same coin, both aspects (i.e., teacher activities and student activities) need to be closely aligned to result in successful personalized learning. A detailed description of the concept of personalized learning, focusing on the two characteristic dimensions and how technology can support the implementation are following in the next section.

Literature review: personalized learning and digital technology

Personalized learning

The idea of tailoring teaching to the individual needs of students has a long tradition in Europe and the Anglo-American countries, and it is discussed in connection with several educational approaches, for example individualization, differentiation, student-centered education, constructivist teaching practices, self-regulated learning, or adaptive learning (Keefe, 2007; Stebler et al., 2018). The relatively new and popular term “personalized learning” links up with this idea. Several English-speaking countries have initiated educational reforms that are aimed at personalized learning and rely, among other things, on the help of digital technology. For example, the most recent US Education legislation—Every Student Succeed Act (ESSA) of, 2015—intends to enhance personalized learning by digital technology and financially supports programs in this area in the hope of improving the quality of instruction and thus the learning success of all students. However, it remains an open question what definition of personalized learning the ESSA uses as a guideline (Zhang et al., 2020b). In the year, 2010, the US Department of Education already described personalization in the “Education Technology Plan” as an extension of individualization (adaptation of the pace of learning to the individual learner) and differentiation (adaptation of teaching methods to learning preferences). Not only the pace and the method can vary, but also the learning goals and the contents. The UK Department for Education and Skills initiated one of the first educational reforms that explicitly referred to the term “personalization”. In the report “Schooling for Tomorrow—Personalising Education,” personalized learning was defined according to five dimensions: 1. assessment for learning: giving students individual feedback and setting suitable learning objectives; 2. teaching and learning strategies based on the individual needs; 3. curriculum choices; 4. a student-centered approach to school organization; 5. strong partnerships beyond the school (Miliband, 2006). The document does not explicitly mention the role of digital technology, but in the research report by Sebba et al. (2007) it was analyzed within the second dimension “teaching and learning”, In sum, they located the potential of digital technology in the provision of learning resources and in the evaluation of student performance.

Although various researchers have investigated personalized learning and the role of digital technology beyond these educational policies and initiatives, a common understanding of how personalized learning is to be defined and operationalized is still missing. Further, the change from “one-size-fits-all” education with a strong teacher-orientation to student-centered education has been called for a long time and is not a novelty of personalized learning. Rather, constructivist learning theory in general holds that the active learner and his or her individual needs must be at the center in order to achieve optimal progress in learning. Even though some meta-analyses support the positive effect of such student-centered approaches (Cornelius-White, 2007), researchers have criticized forms of self-directed learning and questioned their effectiveness (Hattie, 2008; Sweller et al., 2007).

Today, there is a marked tendency towards student-centered teaching methods that provide an appropriate combination of student self-direction and teacher scaffolding (Lazonder & Harmsen, 2016; Reigeluth et al., 2017). For example, some schools with personalized learning concepts no longer have only subjects in their timetable, but also slots for self-directed learning, where students work on their personal learning plans and teachers support them individually (Schmid & Petko, 2019). This form of active participation enables students’ voice and choice. This means that students co-determine their learning in terms of the place, time, content, and social form of learning and with respect to the assessment of their learning process. Some researchers consider the focus on students’ voice and choice as the most significant feature of personalization, which also distinguishes this pedagogical concept from similar concepts such as differentiation and individualization (Bray & McClaskey, 2015; Miliband, 2006).

Empirical research on the use of digital technology in personalized learning settings

In spite of the conceptual fuzziness of personalized learning, several empirical studies have evaluated digital technology-enhanced personalized learning and meta-studies have emerged (e.g., Xie et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020a). Most research has investigated adaptive learning technology that tailors education to an individual student’s needs. This means that students are provided with a specific software that monitors and assesses their learning process and adapts the learning tasks accordingly (Lee et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020a). Comparatively little research has examined how digital tools are generally used in schools with personalized learning settings (e.g., Bingham et al., 2018). A systematic review of empirical research shows that more than two thirds of the studies that had been conducted between 2006 and 2019 examined specific digital systems or tools that aim to enhance personalized learning in a specific course or group of students (Zhang et al., 2020a). Given that many schools have been gradually changing their teaching and learning towards personalized learning without integrating a specific digital system or tool, it seems, that research should more often focus on the different ways in which digital technology is used within the implemented educational practices of personalized learning (Bingham et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018).

In general, the inclusion of different technological tools can significantly support the implementation and the development of personalized learning settings (Bingham et al., 2018; Dabbagh & Castaneda, 2020; Lee et al., 2018; Underwood et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2020a). For example, teachers can use digital technology to make the organization and the management of their personalized teaching practices more efficient. The time saved can be used to provide individual support to each student (Reigeluth, 2017). This potential as described by Reigeluth (2017) is in line with the results of a study on the functions of digital technology in personalized learning in which eighty percent of the teachers used digital technology primarily for planning and instruction in primary and secondary schools (Lee et al., 2018). These schools adapted learning content and instructional methods to the individual learners. The extent to which students have a say in the learning process remains unclear from the study (Lee et al., 2018). However, digital technology can also be useful for lending individual support. If a student has not yet understood a type of task, he or she can receive an infinite number of similar exercises that are generated by a specialized software (Reigeluth, 2017). Furthermore, digital technology can help create immersive and authentic tasks. Students can work with real-world problems and, due to the simplified access to information, also deal with a variety of new problems. In this way, the tasks become relevant and meaningful to the students, which Walkington and Bernacki (2018) emphasize as a crucial aspect of personalized instruction.

Two further studies on personalized approaches from the United Kingdom show that digital technology plays a significant role in enabling individual learning pathways, monitoring individual progress, and allowing the students to work at their own pace (Sebba et al., 2007; Underwood et al., 2007). However, the effective use of technological tools requires an adequate infrastructure and IT concept. A collective case study in the US concluded that certain infrastructural conditions, for instance sufficient internet bandwidth for high-level use of digital technology, must be ensured prior to the school-wide implementation of personalized learning if this approach is to be successful (Bingham et al., 2018). In accordance with this finding, US data show that since the beginning of the, 2000s, external barriers to the integration of digital technology such as insufficient equipment with hardware and software have been significantly reduced (Ertmer et al., 2012). Infrastructure is an important basic condition indeed, but the integration of digital technology into classroom learning is a complex process with several interacting factors at the level of both the individual school and the teacher, which is why even a high standard of hardware and software does not necessarily lead to a more frequent and more effective integration of digital tools (Niederhauser & Lindstrom, 2018; Petko et al., 2018). This assumption can be supported by studies that have identified the individual beliefs of teachers about the use of digital technology as one of the most important factors with respect to whether they use digital technology in the classroom on a regular basis (Ertmer et al., 2012).

Furthermore, several studies indicate that teachers and students use computers more frequently in student-centered and individualized learning settings than in traditional whole-class settings (Law et al., 2008; OECD, 2015; Tondeur et al., 2017). Even though the approach of personalized learning is less established in the German-speaking part of Europe than in English-speaking countries, a Swiss study on personalized learning and digital technology supports this result. More than twice as many students who were taught in personalized learning settings reported to use digital technology at least once a week compared to students who were taught in traditional learning settings (Schmid & Petko, 2019). Nevertheless, it is still unclear how digital technology is concretely used in practice to facilitate personalized learning settings.

Purpose of the study and research question

As the overview of the current state of research shows, there are several empirical studies on personalized learning that demonstrate the potential of digital tools or systems to enable personalized learning environments (Lee et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020a). Further, international findings indicate a higher use of digital technology within personalized learning settings compared to traditional classroom settings (Law et al., 2008; OECD, 2015; Schmid & Petko, 2019). However, empirical research on how digital technology is actually used in schools that have implemented personalized learning school-wide is largely lacking. In order to gain insights into the current practice, the multiple-case study was designed with the aim of investigating the use of digital technology in schools with an implemented personalized learning concept. Accordingly, our research question is:

How is digital technology in general used in schools with a school-wide approach to personalized learning?

Research design and methodology

In order to identify and describe the similarities and differences regarding the purposes of the use of digital technology across and within schools with personalized learning concepts and thus to address the research question, we opted for a multiple-case study (Yin, 2014). Based on a student questionnaire that had already been completed within a major research project on Swiss schools with personalized learning concepts, we selected three schools for data collection. The next section outlines the wider context of our study in more detail.

Contextualization of the study

A growing number of Swiss schools have been changing their culture of teaching and learning by implementing some form of personalized learning. The Swiss research project perLen (“Personalized Learning Concepts in Heterogeneous Learning Groups”) investigated such schools in the German-speaking part of Switzerland over the course of 3 years (2013–2015). Our in-depth study on digital technology use formed part of the perLen project.

Although the participating schools inevitably differ in the details of how they have implemented personalized learning, there are evident commonalities. In a bottom-up initiative, all schools have developed their teaching in terms of student-centered teaching methods, self-directed learning, and adaptive learner support. For this purpose, they have integrated regular time slots in the schedule in which the students learn autonomously according to a personal learning plan. In particular during such self-directed learning phases, students have more choice and voice concerning what, how, and when they learn than in traditional classroom settings. As a consequence, the function of the teachers primarily consists in providing adaptive support during the self-directed learning phases.

Selection of the three case-study schools

All schools of the study participated voluntarily. They had either responded to an open call for schools with personalized learning concepts, or they had been explicitly invited on recommendation from municipal and cantonal education departments. The overall sample of the study on digital technology use consisted of 31 lower-secondary schools with a total of 1017 8th-grade students. They completed an online questionnaire that included the question of how often they use digital technology for different classroom activities. Based on the students’ answers, we identified the three schools with the most frequent use of digital technology and invited them to take part in our multiple-case study. We first contacted the principals via e-mail and called them a few days later, asking for permission for a school visit with different interviews and observation sequences. After having consulted the teachers, all principals agreed to participate.

The Swiss education system assigns post-primary students to three different tracks in lower secondary education: “Gymnasium” (advanced level), Track A (challenging level) and Track B (basic level). The three schools of our subsample all offer education for Track-A and Track-B students and in contrast to traditional schools, the instruction takes place partly in mixed groups and partly in different ability groups per subject. They varied in terms of funding, number of students, and demographics and as regards time and reason for implementing personalized learning concepts (see Table 1).

Data sources and data collection

Data collection was guided by our interest in examining the use of digital technology in classes with personalized learning settings from a qualitative point of view. Before visiting the three schools, we collected relevant curriculum documents from their websites. During the 1-day visit in the fall of, 2016, two researchers carried out semi-structured interviews with the principal(s), two teachers and the person or the persons who were in charge of the IT-infrastructure (see Table 1). Throughout the semi-structured interviews, which were the main data collection tool, the researchers focused on the following areas: characteristics of the school, development towards personalized learning environments, role of digital technology in the school, practical use of digital technology in class, assessment of teaching development through digital technology use, role of participants in the use of digital technology and next steps/further development. For example, we asked each participant what role digital technology plays in his or her school.

In total, we conducted 11 interviews with a duration of 22 to 65 min. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed. At the beginning of each interview, we had asked for permission to record it. In addition, we observed and logged open teaching sequences in which the students worked according to individual learning plans. Furthermore, we photographed the learning situations and were allowed to ask the students a few questions which we documented in the field notes.

Data analysis

After the transcription of the interviews, we conducted a qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2010) in which we consulted our observations as recorded in the field notes and the curriculum documents from the websites (Yin, 2014). To identify the purposes of the school-specific use of digital technology, we first condensed each transcript to extract the main statements. Based on these extracts, we wrote a preliminary case report of each school that included the multiple data sources and was structured by three dimensions: 1. school-related factors (e.g., general context and IT equipment), 2. teachers’ skills and beliefs about the use of digital technology, and 3. teaching and learning with digital technology. We chose this analysis structure based on various research findings indicating that the use of digital technology in the classroom is highly dependent on school factors (e.g., a good technical infrastructure and a supportive principal) as well as teachers' beliefs and skills regarding the use of digital technology (Ertmer et al., 2012; Niederhauser & Lindstrom, 2018; Petko et al., 2018; Tondeur et al., 2017). After this preparatory work, we conducted the analysis with key categories such as quality of the infrastructure, support, and teachers’ beliefs and skills (Petko et al., 2018). In a recursive process of moving back and forth in the interviews, we continuously adjusted the key categories to the data material, which are also structured according to the three dimensions (see Appendix Table 2). This final analysis was added to the case reports in which concrete quotes served to substantiate the findings.

Credibility and trustworthiness

Reliability and validity as criteria for scientifically solid measurements are common in quantitative research but problematic in qualitative research. Therefore, qualitative approaches often replace them by alternative criteria such as credibility and trustworthiness (Twining et al., 2017). In our study, we tried to ensure credibility through the triangulation of multiple data sources (inter alia, student questionnaire, interviews with principals, teachers and IT support, and curriculum documents from the websites). A further measure to increase the trustworthiness of the findings was to involve co-researchers in data collection and data analysis. Moreover, we presented the results to the schools to confirm our conclusions from the perspective of the participants themselves.

Results

In this section, we present the results of the three case studies separately and structure our portraits according to the three dimensions that constituted the basic framework of our analysis (see “Data analysis” section): (1) school-related factors, (2) teachers’ skills and beliefs about the use of digital technology, and (3) teaching and learning with digital technology.

School A: selective use of digital technology according to individual teacher preference—“it depends largely on the assignments” and “it’s a matter of taste”

School A is a public lower-secondary school and located in a large canton in Switzerland. Approximately 300 students are taught by about 30 teachers. The village on a hill with a view of the lake has a higher tax income than the average Swiss village, which can have an advantageous effect on local education policy (e.g., better equipment of schools with infrastructure).

School-related factors

As the number of students had decreased over the last few years through a lower birth rate in the school district, the school was faced with the necessity to adapt its structures. At present, it runs only three classes per grade instead of the formerly four classes. This cut resulted in a structural problem because the school was no longer able to run two Track-A classes (challenging level) and two Track-B classes (basic level) every year. Consequently, the opportunity for students to join a Track-A class varied from school year to school year. According to the principal, the school was motivated to improve this inadequate (“bad”) system.

In order to provide high-quality education in spite of the student decline, the school decided personalized learning as its new system and thus abolished separated Track-A and Track-B classes. The school changed its teaching to personalized learning in partly mixed classes and partly ability groups per subject within eight months. The local school authorities agreed to the new teaching principle but on condition that the percentage of students passing to the “Gymnasium” at least remains the same or increases. This has been achieved with a slight increase in student performance. Today, the students spend one third of their time in self-directed learning phases in mixed classes while input lessons in the subjects mathematics, German, French, and English are held in ability groups. During the self-directed learning phases, each student works on her or his individually designed desk in a large room—the so-called learning landscape, which looks like an open-plan office. In contrast to the classroom for input lessons, the learning landscape accommodates all 50 to 60 students of the same grade.

The IT infrastructure in the classrooms for input lessons presents itself as heterogeneous. Although each classroom is equipped with a projector and cable internet access—“that’s a must, anyway” (Principal A1), all rooms lack a “standard” equipment and open wireless internet access. However, the main problem was stated by Teacher A2 as follows: “We have a great infrastructure for instructional teaching [during the input lessons], but not a good one for group work or individual practice”. Moreover, Principal A1 expressed the wish to have some mobile devices in every classroom whereas at present, each learning landscape is equipped with 15 to 20 computers as standing workstations that can be used during the self-directed learning phases. These computers are suitable for individual work, but as speaking is not allowed in the learning landscape, they cannot be used for group work.

The school finds itself in the comparatively privileged situation that an inhouse computer scientist maintains all 260 school devices. Even though Principal I perceives the IT infrastructure as quite outdated and is determined to improve it, the interviewed teachers regard it as generally good.

The use of educational digital technology and the diverging opinions concerning this issue are an often-discussed topic, but the inclusion of digital tools is “definitively no element of the school profile” (Teacher A2). This statement corresponds with the stance of Principal A1 who does not push the teachers in terms of digital technology integration. Rather, he is confident that digital technology integration in class will evolve naturally, driven by the younger teachers. The development of an IT concept for the school has recently been initiated but at present there are no school-internal general rules for the (student) use of digital technology. Probably due to the few specifications at the level of the whole school, there is a remarkably pronounced informal exchange among the teachers to which they refer as “open-door policy and discussions”, especially within the individual teams who are jointly in charge of all of the students in one grade (see also “Teaching and learning with digital technology” section).

Teachers’ skills and beliefs about the use of digital technology

Various statements point to a large discrepancy between the different teachers’ beliefs about the use of digital technology. Teacher A2 uses digital technology in class regularly and states: “This is the information medium that we all use; they [the students] need to learn how to handle it”. This quote illustrates that some teachers see digital devices as an integral part of everyday life so that their routine use in the classroom becomes indispensable if school is to prepare students adequately for the future. Other teachers, by contrast, wish to restrict the students’ working time on computers. Older teachers in particular tend to hold more negative beliefs than the younger teachers, which is reflected in the frequency of use of digital technology in class and in line with the observations on site. Principal A1 comments on this observation as follows:

My school team comprises a lot of older people too. I can imagine that in 10 to 15 years a lot of young people will have arrived who use computers in their everyday school life much more often and consider them useful.

While mentioning their beliefs, the teachers hardly ever brought up their skills regarding the use of digital technology. Teacher A3 mentions only in passing that they have a very good IT infrastructure, but that one has to know how to use it. Overall, however, the teachers’ digital technology skills appear to be a minor issue.

Teaching and learning with digital technology

As stated in Section “School-related factors”, School A has no general teaching concept regarding the use of digital technology. Each teacher is responsible for her or his subject. This includes assigning tasks for the self-directed learning phase, collecting the students’ work if necessary and correcting it. The integration of digital technology is subject-specific. On the one hand, “it depends largely on the assignments” (Teacher A3) and, on the other hand, on the teacher: “It’s a matter of taste” (Teacher I.1). Nevertheless, the team members who are jointly responsible for the same grade need to find common ground, as Teacher A2 explains: “This [the shared basis] was arranged but has not been written down”, The common standard of the team of Teacher A3, for example, requires that “the students must be able to justify why they are working on the computer”, In joint efforts to define standards, quality is often an issue. In this connection, the teachers regularly discuss “for which assignments it makes sense to use a computer” (Teacher A3). A few years ago, “everybody used computers” (Teacher A2), which is why the discussion about quality has arisen. At the same time, students receive no education in media and computer sciences during their first two years. This proves to be a challenge.

Depending on the task, Teacher A2 begins with a guided sequence on the computer and explains:

… If the learning landscape is free, I can introduce and guide the students on the computer in the learning landscape. For example, when they are preparing a presentation, I tell them not to start simply by designing the PPP [PowerPoint Presentation]. Otherwise, they design 5 hours and still have no content. In this way, I can point out that research comes first.

In the context of the input lessons, teachers mostly use the projector and the interactive whiteboard. Teacher A2 was “totally stuck” when the projector did not work for 2 months: “You need the computer a lot as a teacher”, Teacher A3 points out that the administration is easier to manage: “I can show the worksheet I want to discuss in 2 clicks”, Furthermore, newer teaching materials such as the textbooks for English as a foreign language are increasingly interactive in design and integrate computers. As a consequence, several teachers use interactive teaching materials in which tasks have been redesigned through the use of digital technology. A similar example is the learning software “Religiopolis” that allows the students “to immerse in the worlds of religion” (Teacher A2), which would not be possible to the same extent without digital technology.

In the context of self-directed learning phases, Teacher A2 describes it as “pretty cool” that she can provide her students with the new option of completing a task with a voice message or a text. Teachers rarely integrate mobile phones in class but “particularly for photos, it is a really simple instrument as well. We no longer have a class-set of cameras [one camera per student]” (Teacher A2). In mathematics, the students have access to all solutions on the server so that they can correct and revise their work themselves. Moreover, they practice regularly with a specific learning software. Despite the regular use of digital technology, several teachers try to keep a balance between the analog and the digital, which is reflected in different practices. For example, only certain texts may be written on the computers, and before the online vocabulary training, the students must write down all foreign words by hand at least once.

School B: selective use of digital technology according to individual student preference—“they [the students] are relatively free to decide when they go to the computer”

The small private school is located directly at the bus stop “City Border”, which describes the location exactly. The former factory building has different entrances that give access to the kindergarten, the primary school, and the lower-secondary school. Of the total of approximately 100 students, 35 attend lower-secondary school.

School-related factors

The state-approved private school has been pursuing the approach of personalized learning since its founding year in, 1998. The focus on the students’ “individual development of potential” through personalized learning and smaller class sizes (10 to 12 students) are central characteristics that distinguish this private school from the average public school. Only a small percentage of all students attend private schools in Switzerland because the federal education system is of high quality. Principal B1 explains that this approach, day care from 7:30 to 18:00 as well as bad experiences at previous schools’ cause parents to send their child to this private school. To cover the costs of approximately, 2000 dollars per month excluding meals and schoolbooks, typically both parents have to work.

The heart of the school building is constituted by “Wing A”, which is a large light-flooded room for the self-directed learning phases, so-called “in-depth learning studies”, These in-depth learning studies take place with a frequency of at least one lesson per day. During this time, the students have free access to 12 computer stations. Principal B1 describes them as follows: “The shell of the computers is old, but apart from that they are kept up to date”, Nevertheless, the school plans to replace its IT hardware soon. Teacher B2 is very satisfied with both the infrastructure and the IT support: “Digital media are becoming more and more important. 12 computers for 16 students—that is a big deal […] I always receive support when I need help”, Furthermore, the students have the possibility to bring their own devices. The students use this possibility chiefly to write their final thesis in the last year. During this period, the ICT supporter opens the WI-FI network to the students. For the rest of the year, the students have to use the cable internet.

The smaller rooms for the input lessons are arranged around the main wing. Their IT infrastructure differs and meets the preferences of the teachers as Principal B1 explains. The classroom for mathematics is equipped with a smartboard while other classrooms are equipped with a presenter or only with whiteboards.

In general, the school has not developed a special concept for the use of digital technology. Principal B1 rather sees them as an integral part everyday teaching and learning: “If you look at how children handle media in everyday life, the school cannot cut itself off from digital media. […] We have computer stations; they are used daily. We don’t have ICT lessons once a week; we learn this in the subjects”, Every year, one 9th-grade student acts as the contact person for computer problems and helps the others. Usually, this student intends to begin an apprenticeship in the ICT sector after the completion of compulsory education.

Principal B1 was a driving force behind the digitalization strategy at his school: “At the organizational, level everything is digital”, For example, the documents concerning the team meetings are stored in a cloud and the students’ week plans are published on the intranet, which is especially appreciated by parents. Furthermore, the teachers use a specific platform as a “management tool” to document the discussions with parents. In contrast to the organizational level, the use of digital technology in the classroom varies considerably. There is neither a school-wide discussion nor clarity about the goals of the use of digital technology. The existing exchange among the teachers is limited to application-related knowledge, for example to topics such as “how Apple TV works” (Teacher B2).

Teachers’ skills and beliefs about the use of digital technology

As mentioned in “School-related factors” section, the use of digital technology in class varies, and Teacher B2 describes it as “autarkic and type-depended”. Overall, the majority of teachers see added value in the use of digital technology. Still, a few older teachers do without the support of digital technology due to their negative beliefs about the use of digital technology:

Not everyone works so much with digital media. It depends on the age. One teacher still does everything on paper, and that works greatly because she has such an attitude. […] I hardly write on the blackboard anymore. It really depends on the type. You realize it when Dropbox doesn’t work; some are affected, others not, (Teacher B2)

The interview with ICT Supporter B3 shows that he expects every teacher to have a certain level of digital skills, although a few older teachers have to acquire these skills first: “I expect teachers to be skilled in this area [integration of digital technology]. The younger ones find it easier”, Principal B1 notices the differences in terms of skills and beliefs as well. Therefore, he has initiated an effort to increase the integration of digital technology in class “step by step”. For the majority of teachers, digital technology already plays a major role in their daily practice: “[…] we noticed it last week when the Internet went down. It was a disaster”. (Teacher B2).

Teaching and learning with digital technology

Despite the largely autonomous and type-dependent integration of digital technology, there is one common rule: the students are allowed to use the computers from 8:15 to 9:00 am, that is, before school officially begins. During this time, the students are not required to ask a teacher for permission. Many students voluntarily go to school a little earlier and use the computers for private and school purposes. Furthermore, the students are allowed to use a computer in pairs. To document the students’ tasks, the teachers can avail themselves of an administration platform. Within the platform it is possible to assign each task to a student. Teacher B3 explains his routine as follows: “When the student has completed the task, I enter it into the platform. […] It would be the goal that the students use it in the same way as I do”, At the moment, the students cannot yet access the platform. However, the first step is that all teachers work with it, as so far only a few of them use the platform actively.

During the input lessons, the teachers—except for a few older teachers—often show movie sequences with Apple TV, Netflix, or YouTube to impart languages with authentic situations: “In the past you had to roll the TV in [into the classroom]. Now, my biggest problem is when I have no connection to Netflix” (Teacher B2). Teachers often use YouTube in class, for example to show experiments in chemistry. “We don’t have a large lab like many public schools” (Teacher B3). Therefore, videos are the only way to illustrate complex experiments. For instructions in general, many teachers use the digital presenter and the smartboard, which does not change the teaching practice in itself but is thought to lead to a functional advantage. In this connection, Teacher B2 also points out that the integration of digital technology has become easier in general and helps achieve increased flexibility.

Particularly in vocational preparation, computers play a crucial role. A special platform called “yousty” helps administrate all application documents. The teacher can proofread a student’s application and, at the same time, the platform displays the number of applications and rejections, which means an administrative ease for the teacher. The students can access over, 200 portraits of professions that are complemented with videos and further information about the requisite qualifications, salary, further-education opportunities, open positions in the different cantons, etc. This systematically edited information is intended to make the wide range of professions visible and illustrates through videos and interviews what the professional activity looks like. This comprehensive insight is a great help for the students and proves the potential of digital technology.

If students work independently in the self-directed learning phases, they use digital technology mainly for “searching information, writing, and presentations” (Teacher B2) and occasionally for special projects such as the designing of a website or a newspaper project. The students decide themselves whether they want to work on the computers, and they may also use them for group work: “They [the students] are relatively free in terms of when they go to the computer within the assignments. […] I say, if you don’t know something, do a research” (Teacher B2). The autonomous search for information enables the teacher to split up and distribute assignments thematically, for example “each student can deal with another country”, However, some students need support to find information, for example, where to find application templates: “The students are familiar with Instagram on their mobile phones but not with Word on the computers” (Teacher B2).

School C: structural use of digital technology according to a school-wide strategy—“it has no longer been possible to work without a computer”

The public lower-secondary school with about 300 students and 50 teachers is large in comparison to the average Swiss school and located at the edge of extensive agricultural land. The old school building has existed for more than forty years. In order to accommodate the growing number of students, a further school building for 150 students with a large gymnasium has been planned.

School-related factors

The vast majority of the students take the big step into the professional world after the completion of their compulsory education and begin an apprenticeship. Due to great heterogeneity and large classes, the two co-principals had looked for a better solution with the aim of meeting the diverse needs of the students better without exceeding the financial framework. At the same time, the principals intended to strengthen the students’ personal responsibility and their self-determination. Against this background, the principals have introduced personalized learning as a new teaching system grade by grade and not “in one go” (Principal C1). This systematic procedure allowed new students to enter lower-secondary education in the new system while the students of higher grades could finish school in the old system. Furthermore, this undertaking resulted in the parallel existence of two different teaching systems for 2 years, which was advantageous to the students and helpful to get the commitment of the parents but also difficult for the teachers. The exchange among the teachers was limited due to the distinct challenges they had to cope with, and it led to a temporary split in the team.

The implementation of the new teaching and learning system merged three classes into one “learning studio”, which is one big room for about 50 students. The students learn in a self-directed way for about one third of the lessons in these learning studios. The system is comparable to the concept of School A, but School C runs two learning studios per grade, one “high performance”-group and one “moderate performance”-group. The traditional input lessons in the subjects mathematics, French and English, by contrast, are held in three different ability groups. Furthermore, the school has introduced learning platforms that facilitate the organization of the new teaching and learning system (see “Teaching and learning with digital technology” section). Each learning studio is equipped with 12 computer stations and one can with 17 laptops. ICT Supporter C5 explains the intention behind the acquisition of these devices as follows: “On the one hand, we wanted to have fixed computer stations for the students in the learning studio that were freely accessible. On the other hand, if you want to work with the class on digital devices, it requires a class set”, This “luxury” IT infrastructure with approximately 30 devices for 50 students led to an increased use, which, in turn, requires arrangements among the teachers so as to avoid bottlenecks. Overall, the acquisition of the IT infrastructure was significantly influenced by financial aspects: “[…] Laptops have become cheaper and cheaper, so it is not an educational decision that today there is a laptop cart in every learning studio” (ICT Supporter C5). The previous IT expansion was possible without an overarching concept. However, plans to develop an IT concept already exist. ICT Supporters C5 and C6 have only four hours per year at their disposal to maintain all devices. Because of these limited resources, all devices have the same interface so that in case of problems, all teachers can help each other.

Although the principals introduced learning platforms as central elements of the teaching organization, they hold that “digital technology must be useful, but not central”, As the students already use digital technology in their leisure time very often, Principal C1 rather sees a need for countermeasures. Mobile phones, for instance, are forbidden in the school buildings; only their use on the playground is allowed. Although Principal C2 does not see the solution in implementing new devices either, he considers frontal teaching to belong to the pedagogical Middle Ages. Overall, the principals regard digital technology as a “helpful tool extension”, but they focus on the pedagogical concept. At the same time, the ICT supporters as well as the teachers emphasize the importance of digital technology in the new school model:

-

“With the new school model, it has no longer been possible to work without a computer, to give assignments, to control the entire learning process”, (ICT Supporter C5).

-

“It would also work without digital technology, slower though, and we would have to modify the whole organization of the assignments again”, (Teacher C3).

-

“We are certainly more dependent on digital technology than a normal school”, (Teacher C4).

In contrast to most schools, the teachers who are jointly in charge of a grade prepare the teaching materials together. This means that one teacher is responsible for one or two subjects and afterwards six other teachers use this preparation in class. The whole process of preparation and exchange of the materials is digitalized. In the teachers’ opinion, the (digital) exchange of the materials increases their quality although this practice sometimes leads to discussions concerning the “different levels of quality” (Teacher C4). Mostly, however, discussions on digital technology use are limited to organizational aspects to avoid infrastructure bottlenecks.

Teachers’ skills and beliefs about the use of digital technology

As the school has been working with the learning platforms and the joint digital preparation of lessons for several years, there are hardly any negative beliefs about the use of digital technology. Teacher C3 and Teacher C4 perceive the use of digital technology as “actually simply pleasant” and as “an added value and no disadvantage in today’s world”, Moreover, Teacher C3 explains that most of the new teachers had already worked at the school as interns or substitutes before they joined the regular team. Thus, all new teachers are already familiar with the digitally enhanced teaching system and make a conscious decision to teach in this way. Against this background it seems likely that, teachers with pronounced negative beliefs about the use of digital technology left the school in the past years.

The requisite digital skills challenge some teachers, especially the older teachers. All interviewed persons state independently that younger teachers have higher digital skills than older teachers. In the context of the implementation of a new learning platform, ICT Supporter C6 draws the following conclusion: “It is good for some teachers that they retire next year. It is probably not a big change for the young ones coming from the university of teacher education, simply a new interface”, The principals too know about the different levels of digital skills: “New teachers have no problem; digital media are omnipresent at the university of teacher education […] There are more teachers at my age [50+ years] who have problems” (Principal C2). The majority of teachers feel competent in the use of digital technology and help each other when they are facing difficulties. A few teachers even possess above-average digital skills and are referred to as the “2 to 3 cracks in the house” (Teacher C4).

Teaching and learning with digital technology

As mentioned in “School-related factors” section, the school uses a self-developed learning platform that is crucial to its organization of teaching, especially during the self-directed learning phases. Teachers and students use the learning platform primarily to get an overview of the pending assignments. The teachers record each assignment on the learning platform. Every assignment receives a barcode, which is needed for the administration of completed assignments. Afterwards, the digital component disappears to a great extent, however, because the teachers print out all assignments for the students and distribute them every Monday. ICT Supporter C6 comments on this practice as follows: “[I]t is madness to print out all assignments. There would be more elegant digital solutions. But it is currently financially not possible to provide every student with a device”, If a student does not submit an assignment within the deadline and consequently the barcode is not registered, the assignment will turn red in the system. Students with “red assignments” must attend so-called “in-depth lessons”. Teacher C3 remarks on this new routine in the following words: “I used to make lists to check off… As open and free as it may sound, students have never been so controllable as now. You have it black on white whether it has been handed in or not”. Thus, the learning platform primarily helps the teachers administrate the individual tasks and further serves as “file manager” for the teaching materials.

Teachers use the input lessons to introduce the different assignments. In this context, Teacher C3 explains the students how to set up a PowerPoint presentation, among other things. Teachers often use the laptops for listening tasks in the language subjects. For example, students in pairs watch a French weather forecast on a laptop and answer questions about it. Through the use of the laptops, students can solve authentic tasks cooperatively and at their own pace.

In the self-directed learning phases, teachers often implement learning software. In French and mathematics, the use of software is even prescribed by the official teaching materials. Teacher C4 also uses learning software if a student has not yet understood a particular type of task: “It keeps generating new tasks until you get it. This makes it much easier for me”, During the self-directed learning phases, students are free to decide at what time they deal with which assignment but whether the students are allowed to complete the assignment digitally is usually specified by the teachers. Furthermore, the teachers ensure “a certain individualization” within the assignments (Teacher C3). For example, one task consisted in writing a portrait of a well-known inventor. The students could choose an inventor themselves and searched for information on the internet.

Due to the mixed infrastructure of computer stations and laptops in the learning studios, the school introduced an incentive system for the students: Students can apply for becoming a master learner who has the privilege to use a laptop in the self-directed learning phases. The non-master learner must work on the standing computer stations where the teachers can see the screens better.

Discussion

Summary and conclusions

To gain insights into the practice of using digital technology in schools with personalized learning settings, our study investigated the question as to how digital technology in general is used in schools with a school-wide approach to personalized learning. All three cases illustrate a different practice in terms of the daily use of digital technology in classrooms. Thus, the systematization of the analyses resulted in three different types:

Type A uses digital technology selectively according to individual teacher preference. While each teacher determines the use of digital technology in his or her subject individually, a minimal consensus must be found within the team members who are jointly responsible for the same grade. The teachers regularly discuss how digital technology can add value to specific tasks. The discussions show that especially elderly teachers are still skeptical about the implementation of digital technology. Other teachers, by contrast, aim to impart a competent and meaningful way of using digital and analog media. Although the use of digital technology is neither a constitutive of the school profile nor are general school-internal rules defined, this selective use of digital technology in personalized learning settings leads to some administrative simplifications, functional improvements and enables occasionally new types of assignments. Students gain more scope for choice, especially in self-directed learning phases in which they work with their individual learning plans. At the same time, some teachers restrict the students’ choice in terms of the use of digital devices to the extent that they have to justify why they need to work digitally.

Type B uses digital technology selectively according to individual student preference. Especially in the first lesson and during the self-directed learning phases, the students can decide by themselves whether they want to use the computers for assignments. The implementation of digital technology is already a matter of routine for most teachers. Nevertheless, the use of digital technology in the classroom is not yet systematic in contrast to the organization at school level which runs completely digital. The principal accelerates the process of integrating digital technology in the classroom, but gradually so as not to disparage few teachers with negative ICT beliefs. As the interviewed teachers stated, their use of digital technology in personalized learning settings enables more flexibility in teaching and more choice for the students. The potential of the digital technology seems to be well exploited in some areas. The subject “occupational studies”, for example, could not be taught in the same quality and degree of personalization without the involvement of digital technology.

Type C uses digital technology systematically according to a school-wide strategy. The systematic and frequent use of the learning platform facilitates the administration of the new teaching system and is primarily seen as an administrative simplification for the teachers. Overall, the teachers consider the implementation of digital technology to be supportive and beneficial. The principals are more skeptical than the teachers in terms of using digital technology in class and deliberately do not promote the implementation of digital technology because of the students’ high use of digital technology at home. Their focus is on pedagogical development whereby digital technology integration is seen as a helpful support. The personalization of the learning process is achieved through assignments with student choice and increased autonomy during the self-directed learning phases. Furthermore, the mostly predefined use of digital technology promotes individualization besides interactivity. Moreover, the teachers differentiate by dividing the students into ability groups during the self-directed learning phases and the input lessons.

Against the background of these three types, the teachers at all schools often use digital technology to plan, organize, and administer lessons, which is in line with the findings of Lee et al. (2018). Although student use of digital technology in class takes place on a regular basis it is still less pronounced compared to teacher use of digital technology, despite the availability of adequate IT infrastructure. The students use digital technology regularly and mainly during the self-directed learning phases, which is a commonality that is shared by all three schools. Therefore, such phases seem to be particularly suitable for implementing digital technology in classrooms. This finding is consistent with much of the research on the general integration of educational digital technology in schools that showed that the inclusion of digital tools is more likely in student-centered approaches than in traditional teaching settings (Kim et al., 2014; OECD, 2015; Tondeur et al., 2017). Moreover, meta-analytical findings suggest that student learning with digital technology is more effective when it is combined with student-centered approaches (Tamim et al., 2011).

Apart from the corroboration of previous research findings, our study also reveals some frictions between the common understanding based on the literature review that personalized learning and digital technology can be considered to go hand in hand (ESSA, 2015; Lee et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2019). It becomes apparent that although the three case studies relate to schools with a relatively frequent use of digital technology in comparison to the average Swiss school (see “Selection of the three case-study schools” section) (Schmid & Petko, 2019), it is contrary to our expectations that even in these schools, digital technology did not play a major role in promoting personalized learning. In School A and School B, digital technology was only marginally at issue in the development of their concept of personalized learning. Instead, it was declared to be an optional tool for teachers (School A) or students (School B). This lack of anchoring of digital technology in the implementation strategy stands in marked contrast to the research literature according to which digital technology is to be regarded as a central aspect of the promotion of personalized learning (Bingham et al., 2018; Dabbagh & Castaneda, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). In School C, digital technology is systematically applied to organize the administration of the personalized teaching system. Nevertheless, also in this case, the software merely serves to facilitate the flow of information from student to teachers and vice versa, but it does not in itself and directly contribute to increasing adaptivity (Xie et al., 2019). Rather, it is intended to support teachers in providing adaptive guidance. These unexpected findings show how important it is to investigate the actual use of digital technology in practice which does not always match the innovative uses of digital tools for personalized learning that are typically described in the literature (Bingham et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018). Further, the case studies illustrate that quantitative data on the frequency of digital technology use are not sufficient to analyze whether the actual use of digital technology in practice promotes personalized learning settings.

Despite the absence of digital technology as one part of the school-wide strategies, students use regularly digital technology in the personalized learning settings. In School A, the students have to justify themselves if they want to work with the computers during the self-directed learning phases. This implies that although increased student choice has been achieved through a shift to personalized learning (Bray & McClaseky, 2015; Miliband, 2006), some teacher teams have imposed restrictions on the students’ use of digital technology. In this regard, critical beliefs of teachers can be conducive to the initiation of a valuable discourse on the quality of the use of digital technology as in School A, but they can also lead to increased regulation and, in consequence, to a limitation of the students’ choice to use digital technology in class (Ertmer et al., 2012). In School B, the personalized learning and teaching system extends the students’ scope and leaves it up to them to decide whether they want to work on computers as well. Most teachers let their students take advantage of digital alternatives. Still, the implementation of digital technology is not yet regulated at the school level. In School C, the systematic use of the platform facilitates the administration of the personalized teaching system (Reigeluth, 2017), but it does not support personalized learning in a direct way. Although the students can choose within assignments, it is mostly the teachers who determine whether digital technology can be used to complete an assignment. As the teachers exchange their self-developed teaching materials with specifications for digital technology use and the master-learner system is implemented in each grade, School C is the only case in which a systematic use of digital technology becomes manifest. The personalization of the learning process is mainly achieved through the design of the task, and digital technology contributes to increasing the degree of individualization and interactivity in learning (Walkington & Bernacki, 2018). Nevertheless, the students’ scope for opting for digital tools remains quite limited.

Considering these observations, the findings are rather disillusioning regarding the used potential of digital technology in schools with a school-wide approach to personalized learning. Our analyses point to a marked discrepancy between the well-researched potential of digital technology to enable and support personalized learning settings and the current, albeit frequent, use of it in practice. At least the three case-study schools do not seem to take (full) advantage of digital technology. While their teaching and learning are already strongly oriented towards the individual needs of the students, the potential of adaptive technology to personalize learning is comparatively little and unsystematically exploited. Nevertheless, all principals and teachers consider their teaching developments towards personalized learning as successful, although with potential for further development. This discrepancy between the ideal and actual practice should be given more attention in research. To understand and overcome the apparent disconnection between expected possibilities to enhance personalized learning and actual use of digital technology in practice, more dialogue between researchers and schools’ practitioners is needed. Researchers could support schools in integrating digital technology from the start in the implementation strategy of personalized learning concepts. Further, advice of researchers on specific adaptive tools could help to promote personalized learning, where the use of digital technology goes beyond organizational and administrative issues. In addition, schools could provide direct feedback if the input of researchers is not sufficiently applicable to practice. Greater collaborative exchange between researchers and schools could also provide input for future research that is better aligned with the needs and conditions of schools.

Limitations and future research

Although our study provides instructive insights into the practice of how digital technology is used in schools with a school-wide approach to personalized learning, it has a number of limitations. The interpretation of the findings rests on the assumption that a comparatively high level of technological modification to traditional forms of teaching is related to a systematic use at the school level. However, it could also be possible that schools with a—according to students’ answers in the questionnaire—less frequent use of digital tools in the classroom have instituted the incorporation of digital technology more systematically at the school level. In order to verify or falsify this assumption, we need further studies with a larger sample whose schools differ in terms of the frequency with which they apply digital technology.

Furthermore, despite the triangulation of data, there may be distortions in the findings because the interviews with merely two teachers from different teams do not provide statements that are representative of all teachers within a school. Regarding the representativity of the sample, it is also important to note that the sample is limited to Switzerland. Therefore, the findings can only partially and cautiously be transferred to other countries. Moreover, the case studies are cross-sectional so that the digital technology-based teaching practices may have changed or further evolved in the meantime. In particular, the recent inclusion of media and computer education in the Swiss K-9 curriculum is likely to have increased the attention that is given to the inclusion digital technology not only in the schools themselves but also in teacher education and in-service training. Thus, it might be worthwhile for future research to focus on the impact of the new subject “Media and Computer Education” on the use digital technology in schools with personalized learning concepts.

References

Bingham, A. J., Pane, J. F., Steiner, E. D., & Hamilton, L. S. (2018). Ahead of the curve: Implementation challenges in personalized learning school models. Educational Policy, 32(3), 454–489.

Bray, B., & McClaskey, K. (2015). Make learning personal: The what, who, wow, where, and why. Sage.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298563

Dabbagh, N., & Castaneda, L. (2020). The PLE as a framework for developing agency in lifelong learning. Educational Technology Research and Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09831-z

Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O., Sendurur, E., & Sendurur, P. (2012). Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Computers & Education, 59(2), 423–435.

Every Student Succeeds Act, 20 U.S.C. §, 6301 (2015).

Gierl, M., Bulut, O., & Zhang, X. (2018). Using computerized formative testing to support personalized learning in higher education. In R. Zheng (Ed.), Digital technologies and instructional design for personalized learning (pp. 99–119). IGI Global.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Huang, Y.-M., Liang, T.-H., Su, Y.-N., & Chen, N.-S. (2012). Empowering personalized learning with an interactive e-book learning system for elementary school students. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(4), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9237-6

Keefe, J. W. (2007). What is personalization? Phi Delta Kappan, 89(3), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170708900312

Kim, R., Olfman, L., Ryan, T., & Eryilmaz, E. (2014). Leveraging a personalized system to improve selfdirected learning in online educational environments. Computers & Education, 70, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.08.006

Law, N., Pelgrum, W. J., & Plomp, T. (2008). Pedagogy and ICT use in schools around the world: Findings from the IEA SITES, 2006 study. Springer.

Lazonder, A. W., & Harmsen, R. (2016). Meta-analysis of inquiry-based learning: Effects of guidance. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 681–718.

Lee, D., Huh, Y., Lin, C.-Y., & Reigeluth, C. M. (2018). Technology functions for personalized learning in learner-centered schools. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(5), 1269–1302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-018-9615-9

Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. In G. Mey & K. Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch qualitative forschung in der psychologie (pp. 601–613). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

McLoughlin, C., & Lee, M. J. W. (2010). Personalised and self-regulated learning in the Web 2.0 era: International exemplars of innovative pedagogy using social software. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1100

Miliband, D. (2006). Choice and voice in personalised learning. In OECD (Ed.), Schooling for tomorrow: Personalising education (pp. 21–30). OECD Publishing.

Nedungadi, P., & Raman, R. (2012). A new approach to personalization: Integrating e-learning and m-learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(4), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9250-9

Niederhauser, D. S., & Lindstrom, D. L. (2018). Instructional Technology integration models and frameworks: Diffusion, competencies, attitudes, and dispositions. In J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K.-W. Lai (Eds.), Second handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education (pp. 335–355). Springer.

OECD. (2015). Students, computers and learning: Making the connection. OECD Publishing.

Pane, J. F., Steiner, E. D., Baird, M. D., Hamilton, L. S., & Pane, J. D. (2017). Informing progress: Insights on personalized learning implementation and effects. RAND Corporation. Retrieved from RAND Corporation website. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2042

Petko, D., Prasse, D., & Cantieni, A. (2018). The interplay of school readiness and teacher readiness for educational technology integration: A structural equation model. Computers in the Schools, 35(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2018.1428007

Petko, D., Schmid, R., Pauli, C., Stebler, R., & Reusser, K. (2017). Personalisiertes Lernen mit digitalen Medien: Neue Potenziale zur Gestaltung schülerorientierter Lehr-und Lernumgebungen. Journal für Schulentwicklung, 3(17), 31–39.

Reigeluth, C. (2017). Designing technology for the learner-centered paradigm of education. In C. M. Reigeluth, B. J. Beatty, & R. D. Myers (Eds.), Instructional-design theories and models, volume IV: The learner-centered paradigm of education (pp. 287–316). Routledge.

Reigeluth, C. M., Myers, R. D., & Lee, D. (2017). The learner-centered paradigm of education. In C. M. Reigeluth, B. J. Beatty, & R. D. Myers (Eds.), Instructional-design theories and models (Vol. IV, pp. 21–48). Routledge.

Schmid, R., & Petko, D. (2019). Does the use of educational technology in personalized learning environments correlate with self-reported digital skills and beliefs of secondary-school students? Computers & Education, 136, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.03.006

Sebba, J., Brown, N., Steward, S., Galton, M., & James, M. (2007). An investigation of personalised learning approaches used by schools. DfES Publications.

Stebler, R., Pauli, C., & Reusser, K. (2018). Personalisiertes Lernen -Zur Analyse eines Bildungsschlagwortes und erste Ergebnisse aus der perLen-Studie. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik, 2(64), 159–178.

Sweller, J., Kirschner, P. A., & Clark, R. E. (2007). Why minimally guided teaching techniques do not work: A reply to commentaries. Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 115–121.

Tamim, R. M., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Abrami, P. C., & Schmid, R. F. (2011). What forty years of research says about the impact of technology on learning: A second-order meta-analysis and validation study. Review of Educational Research, 81(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310393361

Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., Ertmer, P. A., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2017). Understanding the relationship between teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and technology use in education: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9481-2

Twining, P., Heller, R. S., Nussbaum, M., & Tsai, C.-C. (2017). Some guidance on conducting and reporting qualitative studies. Computers & Education, 106, A1–A9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.002

Underwood, J., Baguley, T., Banyard, P., Coyne, E., Farrington-Flint, L., & Selwood, I. (2007). Impact, 2007: Personalising learning with technology. British Educational Communications and Technology Agency.

Waldrip, B., Cox, P., Deed, C., Dorman, J., Edwards, D., Farrelly, C., Keeffe, M., Lovejoy, V., Mow, L., Prain, V., & Sellings, P. (2014). Student perceptions of personalised learning: Development and validation of a questionnaire with regional secondary students. Learning Environments Research, 17(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-014-9163-0

Walkington, C., & Bernacki, M. L. (2018). Personalization of instruction: Design dimensions and implications for cognition. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 50–68.

Walkington, C., & Bernacki, M. L. (2020). Appraising research on personalized learning: Definitions, theoretical alignment, advancements, and future directions. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(3), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1747757

Xie, H., Chu, H.-C., Hwang, G.-J., & Wang, C. C. (2019). Trends and development in technology-enhanced adaptive/personalized learning: A systematic review of journal publications from, 2007 to, 2017. Computers and Education, 140, 103599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103599

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

Zhang, L., Basham, J. D., & Yang, S. (2020a). Understanding the implementation of personalized learning: A research synthesis. Educational Research Review, 31, 100339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100339

Zhang, L., Yang, S., & Carter, R. A. (2020b). Personalized learning and ESSA: What we know and where we go. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(3), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1728448

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Fribourg. This work was supported by the Mercator Foundation under the Grant Number 2011-0244.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with regard to the research that is presented in this manuscript or its funding.

Research involving human participants

This multiple-case study complies with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All authors have materially participated and approved the final article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmid, R., Pauli, C. & Petko, D. Examining the use of digital technology in schools with a school-wide approach to personalized learning. Education Tech Research Dev 71, 367–390 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10167-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10167-z