Abstract

New technology-based firms (NTBFs) present high levels of information asymmetry since knowledge base, the intangibility of assets, and appropriability issues are particularly pronounced. Investors experiment with difficulties in evaluating the quality of NTBFs and look into insights representing the venture's promises and outlooks, and NTBFs need to face limited financing opportunities. Therefore, information asymmetries and moral hazards may influence the financing system of NTBFs. Based on the signaling theory, we propose a configurative approach built on five accessible signals (founders’ education and work experiences, property rights, alliances, and size) to identify combinations of signals conducive to the NTBF reaching a first financial round. By adopting a configurative approach through the qualitative comparative analysis, we advance our understanding of the intricate dynamics between NTBFs and investors, shedding light on the complexity and interplay of various factors influencing the financing outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“Nothing is more important for founders than finding their first check or the investor who will lead their round, and yet, finding the right VCs to invest in their startups is an arduous and agonizing prospectFootnote 1.”

1 Introduction

New technology-based firms (NTBFs) are young and initially small firms operating in high-tech, R&D-intensive, and fast-changing environments (Maine et al. 2010; Rydehell et al. 2018). These firms are often characterized by their potential for rapid growth, disruptive innovation, and higher uncertainty than traditional businesses. Such firms face two fundamental challenges connected to their liabilities of newness. The first is to be resource-constrained, and the second is to be resource-demanding since they need external financial support for survival and growth (Courtney et al. 2017; Minola and Giorgino 2011).

The financial challenges faced by NTBFs are relevant at both theoretical and practical levels. In the initial phase, funding plays a crucial role in providing the essential starting capital for testing and developing new products or services, while also facilitating future rounds of investment for these emerging ventures. Based on Carpenter and Petersen's (2002) research, the rejection of the assumption made by neoclassical investment models concerning perfect and frictionless markets can be attributed to the recognition, as suggested by more recent literature, of information imbalances between founders and investors.

The use of signals to address information asymmetry issues and alleviate uncertainty in the process of resource acquisition has emerged as a prominent theme within the field of new venture financing (Colombo 2021). Without credible signals, investors struggle to discern top-tier emerging enterprises, and simultaneously, these new ventures find it challenging to differentiate themselves from their lower-quality counterparts.

NTBFs commonly display heightened levels of information asymmetry, primarily attributable to the intricate and often obscure nature of the underlying technology. This complexity can pose significant challenges for individuals lacking technical expertise (Colombo and Grilli 2005a; Hogan and Hutson 2007).

Furthermore, in the high-tech sector, marked by its extensive knowledge base, intangible assets, and notable appropriability concerns, these circumstances engender agency costs, making external financing a costly proposition (Minola et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2023). At the same time, due to this opaqueness, investors experiment with difficulties in evaluating the quality of NTBFs and look into insights representing the venture's promises and outlooks (Ko and McKelvie, 2018).

Thus, in this paper, NTBFs serve as an ideal context for studying information asymmetry because their nature often faces higher levels of information asymmetry due to their novelty and high-tech characteristics. Academic literature often utilizes signaling theory to investigate how companies obtain financing. Based on the signaling theory, to bridge the information asymmetry gap with better information, the NTBFs can send signals. These signals encompass observable actions, characteristics, or attributes that the more informed party can utilize to convey information regarding their quality, potential, or credibility to the less informed party, often represented by the potential investor (Baum and Silverman 2004; Hsu and Ziedonis 2008). Some of them concern: characteristics of founders (Bewaji et al. 2015; Frid 2014; Gartner et al. 2012; Gicheva and Link 2013; Haeussler et al. 2014; Talaia et al. 2016; Yang and Berger 2017), main features and novelties of the NTBF (Christine M. Beckman et al. 2007a, b; Cassar 2004; Honjo et al. 2014; Hottenrott et al. 2016; Talaia et al. 2016), or the relationships and partnerships with the external environment (Cassar 2004; Soetanto and van Geenhuizen 2015; Wang and Shapira 2012). The numerousness of the explored signals and the different results obtained by scholars show that the process underlying the financing of an NTBF is as crucial as it is complex, and its understanding is still an open question (Colombo 2021; Misangyi et al. 2016; Vanacker et al. 2020). Most of the available research on this topic is based on a reductionist tenet by seeking linear correlations among organizational signals and the presence or the amount of external financing. The primary aim of using symmetric methods is to investigate the connections among suggested independent and dependent variables, with the intention of uncovering fresh empirical evidence within the realm of entrepreneurial phenomena. For example, researchers using multi-regression analysis or structural equation modeling try to estimate the significant influence (either positive or negative) of each hypothesized independent variable on a dependent variable, ending with a "net-effects" estimation approach to research (Woodside 2013).

Nonetheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that entrepreneurial phenomena inherently display significant heterogeneity, as emphasized by Shane and Venkataraman (2000), and conventional analytic methods offer only relatively sample explanatory models for theory improvement. In this paper, we aim to respond to the call for future research that examines the effect of multiple signals in fundraising, which should be valuable in entrepreneurial settings (Drover et al. 2018; Vanacker et al. 2020). Thus, we provide advancement in the knowledge of signals that can forecast the achievement of financial funds by analyzing the combined effect of factors in adjunction to the net-effects model of causality. So far, the adoption of a model able to capture the variety of solutions related to entrepreneurial behavior can advance the development of knowledge in the complexity of the entrepreneurship field. Thus, our research question is: What factors or combinations are necessary/sufficient to explain the achievement of the first round of external financing for NTBF companies?

To address this research inquiry, we employ fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) as a methodology to discern potential configurational signal pathways that contribute to the capability of NTBFs in securing their initial external funding. As described in Sect. 2.2, previous studies have identified and examined signals that effectively convey valuable information. These indicators can be classified into two broad categories: information signals, which provide insights into the underlying viability of the venture, and interpersonal signals, which offer indications regarding the behavioral traits and collaborative proficiency of the entrepreneur (Huang and Knight 2017). We specifically focused on information signals readily accessible to investors and are, therefore, more likely to be commonly used in investment decision-making. Thus, we considered signals related to the human capital of founders (founders’ education and founders’ work experiences), the relation with the external environment (property rights and alliances), and the size of the founders’ team (measured through the number of employees).

By adopting this configurative model and utilizing fsQCA, we advance our understanding of the intricate dynamics between NTBFs and investors, shedding light on the complexity and interplay of various factors influencing the financing outcomes. This study not only contributes to the theoretical body of knowledge but also provides practical implications for policymakers, investors, and entrepreneurs in NTBFs.

The paper's remainder is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes the proposed theoretical framework and propositions; and Sect. 3 reports the details of applied methodology, the fsQCA approach, and those related to the analyzed cases. Finally, we discuss the results, implications, and suggestions for further research.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Information asymmetry and signaling theory in financing

In various interactions, whether economic or social, the presence of information asymmetry can significantly impact decision-making processes and outcomes. Information asymmetry occurs when one party possesses more information than the other, leading to an imbalance of knowledge and potentially distorting the exchange. This disparity in information can result in market inefficiencies, adverse selection, and moral hazard problems. It is a common feature of market interactions where who offers a good often knows more about its quality than who acquires it. In financial markets, information asymmetry between investors and firms can affect investment decisions and lead to market failures. Recognizing the challenges posed by information asymmetry, economists and social scientists have developed signaling theory to understand how individuals and organizations can mitigate the adverse effects of information asymmetry. The modern theory of markets with asymmetric information is rooted in the work of prizewinners George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph Stiglitz. Here, signals used to bridge the information gap between actors are observable actions, attributes, or characteristics that convey private information to counterparties. By sending credible signals, parties with superior information can reduce information asymmetry and enhance decision-making efficiency. Furthermore, the greater the completeness, objectivity, and public relevance of decision criteria, the more straightforward it becomes to make well-informed decisions. Nevertheless, when confronted with scenarios where information is deficient, subjective, or inaccessible, particularly when it is grounded in unobservable attributes, it becomes necessary to resort to specific proxies or signals. These mechanisms serve the purpose of mitigate the information asymmetry between the parties involved (Spence 1973).

Following their groundbreaking contributions, subsequent research has witnessed numerous applications that expand the scope of signaling theory and reaffirm its significance across various research domains.

In the decision-making process related to funding for NTBFs, information asymmetry is notably exacerbated due to the "liability of newness," which encompasses the challenges stemming from a lack of established reputation or financial track record. Additionally, NTBFs frequently refrain from divulging comprehensive information about the products or services they offer (Cassar 2004; Honjo et al. 2014). This dual challenge compels investors, particularly in the initial funding stages, to explore alternative signals that can effectively convey the potential and prospects of the venture. Some of these signals relate to the relationship between the NTBF and the external environment, while others describe some of the company's characteristics. In his literature review, Colombo (2021) describes new venture financing as a process of persuasion in which entrepreneurs aim to convince investors of their firm's value. The decision of whether to invest or not depends on the criteria used by the investors and the relevant evidence they consider (Chen et al. 2009).

Previous research has extensively explored the efficacy of signals in conveying valuable information, categorizing them into two main types: information signals, which elucidate the inherent viability of a venture, and interpersonal signals, which indicate an entrepreneur's behavior and collaborative capabilities (Huang and Knight 2017). In the context of Venture Capital (VC) financing, information signals that have been found to be effective include metrics related to human capital, preparedness, social capital, technological expertise, government grants, and affiliations with third parties or fellow Venture Capitalists (Bapna 2019; Beckman et al. 2007a, b; Hsu and Ziedonis 2008; Islam et al. 2018; Ko and McKelvie 2018; Matusik et al. 2008; Plummer et al. 2016; Shane and Cable 2002; Vanacker and Forbes 2016).

Conversely, examples of interpersonal signals pertain to an entrepreneur's passion for their venture, personal commitment to its success, and their coachability as an individual (Busenitz et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2009; Ciuchta et al. 2018). More comprehensive insights into the specific signals examined within the literature are elaborated upon in the subsequent section.

2.2 NTBFs financing and signals

Many scholars tried to establish a direct or indirect relationship between alliances or networks and NTBFs' chances of accessing the capital market. Wang and Shapira (2012) demonstrated that alliances with university scientists validate research capabilities for NTBF firms. This effect is even more pronounced when applied to university spin-offs. As noted by Soetanto and van Geenhuizen (2015), factors such as the size, density, and strength of the connections play a pivotal role in enhancing the ability of these spin-offs to secure external funding for their research and development efforts. Furthermore, the maintenance of robust relationships with universities also exerts a positive impact on their capacity to attract external funding. The network approach to entrepreneurship is critical because it provides the entrepreneur access to necessary resources, signaling an entrepreneurial project's value and quality to investors in the capital market (Jenssen and Koenig 2002). Cassar (2004) analyzed the effect of networks and alliances from an informal point of view. He studied the effect of alliances not as signals to formal and external investors but as proper funding channels. The results of this study indicate that companies with relatively fewer tangible assets tend to rely on less formal financing methods, including loans from individuals unaffiliated with the business. These alternative sources of funding play a more substantial role in shaping the capital structure of NTBFs. This fact highlights the importance of network resources in these ventures: The informal actors (family and friends) of a given venture's network may substitute formal investors, especially in the early stages.

Furthermore, an additional signal that has been extensively explored in the literature pertains to innovation capital. Patents and intellectual properties are recognized as influential signals that can shape the decision-making process in financing, mitigating the effects of information asymmetry between Venture Capital Firms (VCFs) and their target firms (Conti et al. 2013; Hoenen et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2016). Specifically, Hoenen et al. (2014) have argued that these information asymmetries tend to diminish as Venture Capital Firms (VCFs) and target firms develop a deeper and more familiar relationship over time. Thus, the value of signals like patents could decrease as the relationship between investors and entrepreneurs continues. Patents serve as valuable mechanisms for safeguarding intellectual property rights. Therefore, entrepreneurial innovators may strategically employ patents as signals to convey the quality of NTBFs to prospective investors (Audretsch et al. 2012). Gompers and Lerner (2001, p. 35) warn, "Although more tangible than an idea, patents and trademarks themselves are not enough to enable a company to obtain financing from most lenders." Sometimes, what is missing is a good trade-off between feasibility and quality that makes financing more accessible. In this case, a critical signal could be represented by the development of a prototype (Audretsch et al. 2012).

Among the most studied internal signals in the financing decision-making process there is the human capital of the NTBFs. This intangible and precious resource is often measured along two dimensions at the founders' level. The first dimension is the founders’ education, and the second is their previous work experience. There are many reasons to consider the founders’ education level as a signal for NTBFs’ investors. For example, the educational backgrounds of members can serve as signals of diversified task orientation within an entrepreneurial team and has demonstrated a positive and significant correlation between this educational diversity and investors' willingness to engage with the venture (Vogel et al. 2014). Talaia et al. (2016) found that higher educational levels are related to higher amounts of capital raised by the NTBF. The research suggests a strong correlation between the capital raised and whether the CEO of NTBFs holds an MBA degree, as entrepreneurs with an MBA degree may enjoy higher credibility in the eyes of potential investors. However, Ratzinger et al. (2018) offer different results, finding that having a founder with a technical education could reduce the likelihood of relying on self-financing but increase the likelihood of securing equity investments. Conversely, teams led by founders with doctoral-level business education are less likely to rely on self-financing and have a higher chance of securing equity investments. Furthermore, Gartner et al. (2012) have demonstrated that individuals with lower levels of education who are prospective entrepreneurs tend to rely on less external financing. This observation may suggest that individuals with less education are either establishing businesses that require less external funding or may face challenges in meeting the eligibility criteria for formalized loans.

The other human capital dimension assessed when considering access to first funding is the founders' work experience. Top management teams with more senior management experience receive VC funding and go public at higher rates (Christine M. Beckman et al. 2007a, b). Talaia and their colleagues arrived at a similar conclusion regarding the significance of managerial experience, utilizing an entrepreneur's age as a proxy for the wealth of experience accumulated over their lifetime. Their assumption is that individuals with more extensive experience, often reflected in their age, tend to be more successful in securing funds due to the knowledge they have gathered throughout their professional journey (Talaia et al. 2016). In addition to age-based experience, industry-specific expertise is also a critical factor in obtaining external funding (Bewaji et al. 2015). VC firms are more inclined to reject entrepreneurs lacking experience in NTBFs due to perceived weaknesses in their team's ability to present a credible marketing strategy (Carpentier and Suret 2015; Haeussler et al. 2014). Furthermore, prior experience in founding entrepreneurial ventures is closely associated with the likelihood of sourcing VC through personal connections, a factor that is also correlated with another critical organizational outcome, namely the time it takes to secure VC funding (Hsu 2007). "Serial entrepreneurs," who have already experienced the foundation of one or more ventures during their career, may have the edge over first-time entrepreneurs in resource acquisition. Entrepreneurs with prior experience in founding ventures that have received VC backing tend to access VC more swiftly and secure larger amounts in their initial funding round compared to novice entrepreneurs. This early-stage advantage appears to stem from the preexisting connections and relationships these entrepreneurs have established with VC investors. Of course, it should be mentioned that not all serial entrepreneurs are necessarily related to successful ventures. Baum and Silverman (2004) found that the number of prior founding in which an NTBF's CEO has been involved hurt VC funding, suggesting that presidents who have experienced entrepreneurial failures in the past may find it more challenging to obtain VCF for future NTBFs. Finally, a recent study by Ko and McKelvie (2018) demonstrated that, through a sample of 235 new ventures, both dimensions of human capital offer precious signals that directly impact the amount of received funding.

Finally, the literature proposes the size and age of the company as signals observed by the investors. Often measured in terms of the number of employees, the size may be controlled as a proxy of the company's life stage. In many cases, it has been found that investors prefer to invest in more structured companies rather than early-stage projects. In particular, small firms may severely fail to provide sufficient collateral value to investors. This effect is even stronger as the firm's small size is combined with an R&D-intensive activity. Financial constraints are severe for R&D-oriented NTBFs since those firms are averse to revealing detailed information about the project that would make it attractive to outside lenders, fearing its disclosure to potential rivals (Honjo et al. 2014). As a result, small firms may have more difficulties conveying their quality to outsiders than big and more structured firms. This result confirmed since what happens mostly is that the larger the NTBF, the more significant the proportion of debt, which results in long-term debt financed by external investors and banks (Cassar 2004; Colombo and Grilli 2005b; Song et al. 2007). Instead, different studies suggest that private investors favor younger firms (Song et al. 2007). For university spin-offs, age is seen as a proxy for the innovation intensity of the company. This implies that companies are better at attracting funding. This evidence is only partially confirmed because age may also be perceived as a proxy for the overall experience level. Thus, VCFs may evaluate older firms positively due to higher experience and survival.

The numerousness of the explored signals and the different results obtained by scholars show that the process underlying the financing of an NTBF is as important as it is complex, and its understanding is still an open question.

Table 1 shows a brief overview of prior related works investigating signals predicting a funding round's achievement.

The current state of the art about NTBF financing predominantly relies on symmetric quantitative methodologies, including multiple regression analysis and structural equation modeling. Much of this research adheres to a reductionist perspective, where the primary aim is to identify linear correlations between organizational signals and the presence or extent of external financing. This approach contrasts with the principles of configurational theory (Meyer et al. 1993). The main purpose of symmetric methods is to test relationships between proposed independent and dependent variables to discover new evidence in entrepreneurial phenomena. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that entrepreneurial phenomena inherently manifest substantial heterogeneity, a notion underscored by Shane and Venkataraman (2000). Traditional analytical methods, while valuable, tend to provide relatively limited explanatory models for advancing theories in this domain. A potential avenue for deriving fresh insights involves the examination of the impact of various factors within the framework of the net-effects model of causality, where the net effect implies that an antecedent variable is positively associated with the dependent variable. However, in a minority of cases, the relationship may be harmful (Douglas and Prentice 2019). So far, adopting a model able to capture the variety of solutions related to entrepreneurial behavior can advance knowledge in entrepreneurship.

2.3 Complex causality with a configurative approach

We found a broader spectrum of methods being utilized, with an increasing number of studies embracing complexity through the application of suitable approaches (Berger 2016). Case-oriented explanations of outcomes frequently adopt a combinatorial approach, emphasizing the specific configurations of causal conditions (Ragin 1987). Instead of concentrating solely on the net effects of causal conditions, case-oriented explanations accentuate their combined effects. This is because distinct pathways can lead to the same ultimate outcome, and these pathways may not necessarily mirror the configurations that explain the absence of the outcome.

A configurational perspective underscores the inherent complexity of causality, characterized by three key features: (a) conjunction, where outcomes typically result from the interplay of multiple conditions rather than a single cause; (b) equifinality, which implies that there can be more than one path leading to a specific outcome; and (c) asymmetry, suggesting that attributes found to be causally related in one configuration may be unrelated or even exhibit an inverse relationship in another.

As articulated by Meyer et al. (1993, p. 1178), these features highlight the intricate nature of causality. QCA serves as a suitable methodology for examining "multiple conjectural causations" of a phenomenon. In this context, "multiple" denotes the existence of various paths that can lead to the same outcome, while "conjectural" signifies that each path represents a combination of conditions (Rihoux and Ragin 2009, p. 8).

This approach, relatively new in social sciences (Marx et al. 2013a, b; Ragin 2008, 2000), is garnering increasing attention within the field of managerial studies. This is evidenced by the growing number of research papers employing this method and subsequently published in high-quality journals (Dy et al. 2005; Greckhamer et al. 2013; Ordanini et al. 2014). This methodology involves transitioning from a comprehensive understanding and analysis of a relatively small to an intermediate number of empirical cases, typically ranging between 5 and 50. The ultimate goal is to identify configurations of causally relevant conditions that are associated with the outcome under investigation (Marx et al. 2013b). As outlined by Ragin, who launched this methodology and its analytical tools, QCA "integrates the best features of the case-oriented approach with the best features of the variable-oriented approach" (Ragin 1987, p. 84).

To explore the various configurations of conditions, qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) employs two prevalent variants: crisp-set (csQCA) and fuzzy-set (fsQCA). CsQCA involves set memberships constrained to binary values, with 0 representing full non-membership and 1 indicating full membership. Instead, in line with Ragin's approach (2008), fsQCA assigns membership values to conditions on a scale ranging from 0.0 (complete non-membership) to 1.0 (full membership), with 0.5 serving as the crossover point or the point of maximum ambiguity. This process is commonly referred to as calibration.

In both variants, the analysis of a relationship is divided into two asymmetric components formalized through set and subset relationships: One focuses on the necessity of conditions regarding the outcome, while the other centers on their sufficiency. This dual approach enables researchers to tackle the complexities of real-world phenomena without imposing a priori simplifications. A causal condition is considered necessary for an outcome if instances of the outcome form a subset of the instances of the causal condition. Conversely, a condition is deemed sufficient if instances of the causal condition constitute a subset of the outcome. Consistency and coverage are the metrics employed to gauge the degree of fitness in subset relations. They evaluate the extent to which identified set-theoretic relations align with empirical cases. Consistency assesses the degree to which a subset relation between a causal condition and an outcome is observed in real data. Once the consistency of a subset relation is assessed, coverage evaluates its empirical relevance (Legewie 2013).

2.4 Research model and propositions

Based on the literature, we test a configurative approach (fsQCA) to search for combinations of signals determining the financing of NTBF. The model relies on the following signals (causal conditions):

-

Founders' work experience (EXP) we expect that this condition is positively related to the outcome since prior studies show that investors attach a high value to the entrepreneurial experience when making their investment decisions (Carpentier and Suret 2015). According to the literature, we consider this signal informative of the founders’ human capital of the NTBF. We observe three types of work experience: foundation, managerial, and technical. The founders' previous experience is measured in terms of the presence in the team of "serial founders" (Ko and McKelvie 2018). Previous technical work experience refers to the experience in the sector to which the NTBF belongs. The managerial experience, on the other hand, includes experience at the level of business and leadership.

-

Founders' education (EDU) this condition is measured as a formal degree obtained at the end of the academic career (Ko and McKelvie 2018). Based on the literature, this factor, alongside the previous one, measures the founders’ human capital. Therefore, we evaluated the presence of this condition by measuring the founders’ education, considering the research doctorate as the maximum level of academic education, followed by master’s degrees, bachelor’s degrees, and high school degrees. Thus, the presence of founders with other education or with lower grades was measured through the last level of the scale used.

-

Size (SIZE) we consider this condition a positive signal for investors and measured it in terms of the number of NTBF's employees. In agreement with (McMahon 2001), we expect that the greater the company's size, the greater the investors' interest.

-

Property rights (IP) the owned patents, patent applications, or other intellectual property rights protection are used as possible signals of an NTBF’s innovation quality. Based on the literature (Conti et al. 2013), we expect that the presence of patents filed by an NTBF is positively related to the likelihood of obtaining financing, especially in the early phases.

-

Alliances (ALL) established relationships with reputable business partners based on research agreements (e.g., with universities, research institutions) and sales agreements (e.g., with pilot customers, sales partners). Studies based on investors’ transaction data show that the number of alliances an NTBF possesses positively relates to the amount of venture capital financing it receives (Baum and Silverman 2004; Greenberg 2013).

Finally, we considered the amount of the first round of financing received from the NTBFs as the outcome (OUTCOME). This means that our results can only be related to the causal complexity behind the outcome rather than its negation (NTBFs never founded), which we leave for future work.

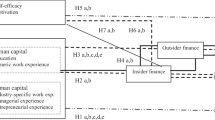

According to Fig. 1, we aim to test the following propositions:

Proposition 1

Obtaining the first round of financing for NTBF companies is linked (in an asymmetric way) to the five selected signals (education, experience, size, intellectual property, and alliances).

Proposition 2

Different signals configurations (recipes) are equifinal to achieve the first round of financing for NTBF companies.

2.5 Data source

We collected data using three different data sources: LinkedIn, Crunchbase, and Orbis. LinkedIn is a professional networking platform with a primary focus on connecting professionals and advancing their careers. It caters to individuals in the professional sphere who aim to establish connections with their peers and cultivate a valuable pool of human resources. In contrast to traditional social networking sites, LinkedIn profiles closely resemble online resumes, providing a comprehensive overview of a user's educational and professional background. Notably, LinkedIn's data surpass the self-reported network data commonly found on other social networks, offering a more objective and trustworthy source of network information (Guillory and Hancock 2012).

However, LinkedIn provides information about social networks but does not provide any information about companies' success. Information on NTBF companies is provided by comprehensive crowdsourced databases such as Crunchbase.com and ORBIS.

Crunchbase is a relatively new commercial database that gathers information about all existing NTBFs, their founders, current status, venture capital, and other funding they have acquired through companies and investors' official statements. This database was created in 2007, but its scope and coverage have increased significantly over the past few years (Dalle et al. 2017). The crowdsourced database has been used in economics and management to study several aspects of the entrepreneurial financial process.

The third database that we used to collect data is ORBIS. This database is maintained by Bureau Van Dijk (a mult-inational company recognized as one of the leaders in distributing economic and financial information in partnership with leading data collection and analysis companies). ORBIS is a commercially available dataset that covers over 200 million firms across the globe. It provides company financials (e.g., operating revenues, employment, fixed capital) and detailed information on firm ownership structure and other firm characteristics.

Using these three databases, we collect data to investigate our propositions.

2.6 Data collection

Our sample is drawn by extracting companies from Crunchbase. We selected the Iberic region to test our model for several reasons. First, the Iberic region is constituted by two similar countries (Portugal and Spain), both considered “moderate innovators” (together with Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia) in the annual European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS) But, while Portugal is a new economy that for a few years has developing and now is attracting an increasing amount of investments, Spain is outperforming its peers in Southern Europe, and is the sixth-largest economy in Europe. An analysis based on a sample consisting of Portuguese and Spanish YBTFs can provide important information about the validity and reliability of the proposed model. The sample will be analyzed differently for reasons that will be explained later.

We decided to extract the companies representing the top 30 Spanish and top 30 Portuguese NTBFs based on the Crunchbase Rank. We first filtered through the Crunchbase interface by the "Headquarters Location" to find Spanish and Portuguese NTBFs. Then, we filtered by industry chosen in both cases, "Information Technology" and "Software."

We obtained 538 Portuguese NTBFs and 3585 Spanish NTBFs. Those results have been sorted through the Crunchbase Rank (CBR). CBR is a dynamic index that measures an entity's prominence based on the number of connections a profile has, the level of community engagement, funding events, news articles, and acquisitions.Footnote 2 In this way, the companies are prioritized by their influence.

We selected the best companies ranked with CBR, and as an extra step, we considered all the NTBFs extracted from Crunchbase with a record in the ORBIS database. This step was done in order to obtain a complete dataset. At the end of the procedure, we selected the first 30 Portuguese NTBFs and the first 30 Spanish NTBFs present at the same time in Crunchbase and ORBIS for triangulation purposes. We collected information about size, sectors, funding rounds, websites, and partnerships based on both databases.

The next step was to consider the composition of the NTBFs’ teams. We collected all the information about the people in charge of the top management team of each NTBF. We then searched all founders’ profiles on LinkedIn and collected information about their education and work experiences.

We finally built the database with all the information needed to construct the explanatory variables and the outcome for the fsQCA model. In summary, the database presents the variables as described in Table 2:

The details of the two databases are reported in Appendix.

2.7 Calibration

Calibration constitutes the method by which unprocessed numerical data, typically measured at the interval or ratio level, undergo a transformation into set membership scores. This transformation is achieved through reference to a specified set of qualitative anchors (Dusa et al. 2017). The heterogeneity of the causal conditions considered in our model did not allow for the use of a single calibration scale. Thus, each condition was calibrated, taking into account its specific nature. We made it through the use of theoretical and substantive knowledge, which is essential to the specification of qualitative breakpoints (Ragin 2009).

As outlined by Douglas et al. (2019), the determination of these breakpoints can be approached in several ways. Researchers may look to established theory to provide theoretical rationales, and refer to external samples for empirical justification, or alternatively, they may rely on the frequency distribution of the sample data for setting the cutoff points.

The calibration process can be executed manually or facilitated by specialized software such as R.Footnote 3 The R package QCA offers functions for conducting qualitative comparative analysis, complemented by a user-friendly graphical interface. This package applies the comparative method initially introduced by Ragin (1987) and subsequently refined by Cronqvist and Berg-Schlosser (2009) and Ragin (2008, 2000). The Quine–McCluskey minimization algorithm, implemented in this package, adheres to mathematical precision, as elaborated in the works of Duşa (2010, 2007; 2017).

Most of our causal conditions were calibrated using the fuzzy-set, while just one causal condition (alliances) was calibrated with a crisp-set. Calibration is a process that yields fuzzy-set membership scores by employing different anchor points. For s-shaped distributions, including the logistic function, three anchors are utilized to either increase or decrease these distributions. In the case of bell-shaped distributions, six anchors are applied for a similar purpose.

The argument thresholds can be specified in two ways: as a simple numeric vector or as a named numeric vector. In the context of s-shaped distributions, the named vector uses the following thresholds: "e" for the full set exclusion, "c" for the set crossover, and "i" for the full set inclusion. Consequently, if the order is e < c < i, the membership function increases from e to i. Conversely, if the order is i < c < e, the membership function decreases from i to e. This approach allows for the manipulation of membership functions to accurately represent the underlying data distribution. Therefore, we first build the raw data table, transforming the collected data into numerical values, then calibrated with the R package (see Table 3).

Regarding the founders' experience and education, the calibration similarly took place to make the most of the information relating to the founders' human capital. In particular, for education, we calculated the average education of the founders of each NTBF, attributing to each founder the value shown in Table 1 based on the last degree of education received (4 for Ph.D., 3 for master’s degree, 2 for bachelor’s degree, 1 for high school, and 0 for no education levels). Therefore, we normalized this average considering a theoretical maximum given by the case in which all the founders of the considered NTBF had a research doctorate. By dividing the education average of the founders of the NTBF by its theoretical maximum, we obtained a value that we called "Point" and calibrated through the indications given in Table 1. According to Low and MacMillan (1988), it is essential to note that in this calibration, we hypothesized that investors should positively consider a higher education level. The same criteria were applied to the founders' work experience; however, this category was first articulated in the following five classes: prior funding experience, managerial skills, and technical skills. For the education condition, we used a scale of 5 items. The highest value (4) was given to the prior funding experience since previous studies show that investors attach a high value to the entrepreneurial experience when making investment decisions (Carpentier and Suret 2015).

Moreover, prior experience may include managerial, business, leadership or technical experiences. According to Macmillan et al. (1987), we ranked managerial, business, and leadership work experience higher than technical work experience. Thus, we assigned a score of 3 to founders who work as CEOs, managers, or directors, 2 to those who work at least in the same sector, 1 for different sectors, and 0 to those with no prior work experience. The procedure used to convert the work experience variable into a fuzzy set is also used for education.

For what concerning size, the NTBF Monitor Report 2018 reports (Steigertahl et al. 2018) that the average of employees in Portugal NTBFs is 8.8 while in Spain, it is 12.7, demonstrating that the Spanish NTBFs are bigger than Portuguese NTBFs. Then, considering the team size as a proxy with larger teams that achieved better outcomes than smaller teams (Cassar 2004; Der Foo et al. 2005), we calibrated this causal condition (using the number of the NTBFs' employees) according to the anchor points reported in Table 3.

According to the literature, patents and other IP assets, such as trademarks, are important signals when investors decide to invest in NTBFs. Moreover, NTBFs applying for both patents and trademarks received a 35.4% higher amount of funding than firms that applied for only one of the two IP rights (Zhou et al. 2016). Therefore, to calibrate the intellectual property rights, we used the anchor points reported in Table 1, assigning 1 if the NTBF owns one or more trademarks, 2 if it owns only patents, and 3 if the NTBF possesses both a patent and a trademark (or more than one).

The causal condition about the presence of alliances does not need to be set as fuzzy since no shades are underlined. Thus, in this research, we manually set the value 1 when the NTBF has a research alliance or a sales agreement (or even both) while we set the value 0 for companies without formal deals. We do that since collaboration with universities helps firms enhance their perceived technology potential (Wang and Shapira 2012), and established relationships with reputable business partners also act as a quality signal (Hoenig and Henkel 2015).

Lastly, as we already said, we analyzed the first round of funding as the outcome, since this is the most common output for research about quality signals and well represents the moment of maximum asymmetry (Bertoni et al. 2011; Greenberg 2013; Hsu and Ziedonis 2008; Ko and McKelvie 2018; Munari and Toschi 2015).

Similar to the causal condition, different thresholds were used for the outcome calibration of the Spanish and Portuguese samples. Thus, we consider that according to the NTBF Ecosystem Report 2017 (Genome 2017) and the analysis extracted from DealroomFootnote 4, in Spain, there is a more considerable amount of money in the first rounds rather than in Portugal (more rounds above 2 million dollars for Spanish NTBFs, while in Portugal mainly all the rounds are in the range 0–1 million).

It is important to note that the calibration considers that our sample includes NTBFs that received at least one round of funding. For this reason, we did not analyze the absence of the outcome.

3 Empirical results

The analysis proposed in this paper aims to answer a specific research question: What factors or combinations are necessary/sufficient to explain the achievement of the first round of external financing for NTBF companies?

Our analysis assumes that the decision-making process underlying the NTBFs’ funding is a complex process in which the emergence of a result cannot be observed through deterministic laws and hypotheses of linear relationships between factors. In the following, we report the empirical results of necessary and sufficient analyses.

3.1 Necessity analysis

While the analysis of sufficient conditional combinations is central to the fsQCA, the necessity of each condition has to be tested prior to constructing a truth table (Schneider and Wagemann 2010). To determine whether any of the five conditions were necessary for securing the first round of financing, we conducted an analysis to ascertain whether a given condition was consistently present (absent) in all cases where the outcome was achieved. Legewie (2013) emphasizes the importance of several key factors when employing QCA tools to ascertain necessary conditions. These factors include the establishment of consistency thresholds and empirical significance, as well as the need for theoretical reflection on the identified conditions, research questions, and coding schemes. To test conditions for their necessity, the recommended threshold for consistency should be 0.9, and its coverage should not be too low 0.5 (Ragin 2008; Schneider and Wagemann 2010). It is important to note that identifying a necessary condition is relatively rare empirically (George and Bennett 2005; Ragin 2009). Thus, the identification of multiple necessary conditions could suggest that the average membership in the outcome is significantly low. In such scenarios, it may be warranted to consider theoretical justifications for recalibrating the outcome set.

As expected, there is no causal condition for both countries whose presence (absence) is necessary to obtain the first loan. In fact, as shown in Tables 4 and 5, no consistency value is more significant than the suggested threshold.

3.2 Sufficiency analysis

In order to find combinations of causal conditions sufficient to generate the outcome, we explored the causal paths computed through the truth table obtained, setting 0.80 as the consistency cutoff value. (This allows us to assign 1 to each outcome with consistency exceeding 0.80 and a value of 0 otherwise.) Figure 2 shows the Venn diagram related to the computed truth table. This diagram was created through the R Studio QCAGUI package. In this diagram, each causal condition is associated with a number (SIZE 1; EXP 2; EDU 3; IP 4; ALL 5), while the signs in each area indicate the value of the outcome (*for OUTCOME = 1; ‡for OUTCOME = 0).

The fsQCA yields three solutions: complex, intermediate, and parsimonious. According to Ragin and Strand's suggestion (2008), we present complex solutions (Figs. 3 and 4), which are often the most interpretable.

The overall consistency and coverage values are greater than the minimum thresholds (0.88–0.63 for the Portuguese sample and 0.93–0.62 for the Spanish sample), and this means that all of the solution paths are informative (Ragin and Strand 2008; Woodside 2013).

3.2.1 Results for the Portuguese sample

Figure 3 shows the causal paths for the emergence of the outcome of the Portuguese NTBFs. Using Boolean operators, the result can be expressed as follows:

These solutions show how the NTBFs reach the outcome (successfully gaining financial resources from external investors during the first round of funding). As shown in Fig. 3, NTBFs that meet the proposed outcome do it through different "recipes" or paths of causal conditions.

More specifically, the complex solution consists of four solution terms. Four NTBFs show a certain degree of membership in the outcome because of the simultaneous presence of high levels of founders' work experience and education and a large team of employees, even when the NTBFs have no intellectual properties (first configuration path: EDU*EXP*SIZE*∼IP). This sufficient configuration achieved a high level of consistency of 0.915 and a relative coverage of 0.331.

Two NTBFs are based in Porto, while the other two come from Leiria and Lisbon. They were founded by a male team and grew after the first funding. The NTBFs are young: Two were founded in 2015 and the other 2 in 2013. Other two are financed by Venture Capitalists, while Private Equity finances the remaining two.

For statistical purposes, in Table 6, we highlight the total value of production from the first registered year to the last documented one in the ORBIS database (2018), and we note that this value grew for every NTBF in the considered time window.

The second path focuses on combining education, size, and alliances with the intellectual property factor's absence. Differently from the first path, here, the experience is replaced by the presence of alliances. (Second configuration path: EDU* *SIZE*∼IP*ALL achieved a level of 0.906 and 0.201 of consistency and coverage, respectively.)

The NTBFs here come from different locations: one in Porto, one other in Coimbra and Lisbon; Venture Capitalists and Private Equity finance them. NTBFs are quite young: Only one of them was founded in 2007, while the remaining two were in 2012 and 2015.

Focusing on the total production value, data are shown in Table 7.

The third term of the solution (third configuration path: EDU*∼SIZE*IP*ALL) showed by 3 Portuguese NTBFs is similar to the second path where, however, the role of patents is replaced by another factor, the number of employees. This path balances the absence of a large number of employees with the presence of an Intellectual Property right. This means that these two factors can be interchanged when combined with a high level of education and the presence of alliances. Even if the literature often links the use of patents to the achievement of funds, in our case, this is the only path in which intellectual property is not negated.

Focusing on the location, NTBFs involved in this path are mainly from Porto, followed by Coimbra and Lisbon. Only one is run by a female team, and 3 NTBFs were founded in 2013, while the other one was in 2014. For what concerns the total value of production, data are reported in Table 8.

Finally, the last term of the solution shows a path empirically detected only in one case. It considers the combination of all the denied factors (absence of patents, low number of employees, and low levels of education) unless the experience of the founders and external alliances. This atypical solution (∼EDU*EXP*∼SIZE*∼IP*ALL) is represented by just one company. In this path, small firms with a low level of education and no IP protection may still accomplish the task of ensuring a significant amount of external resources if they have a high level of experience and some reputable partners. Conversely, this term has the lowest value of raw coverage and unique coverage observed from the other three paths. The company presenting this combination of factors was founded in 2012 by a male team in Lisbon and financed by VCs. After the first round, it received three other rounds for a total of four rounds, and more than ten million were gained. This means that this combination well explains the ability of the NTBF to obtain financing. The total production value rose 639% from 2015 to 2018, as shown in Table 9.

Looking at all the different paths that occur in Portugal's sample, we can underline the importance of experience as the main factor observed by investors. Entrepreneurs with prior firm-founding experience or management experience are expected to have more skills and social connections than novice entrepreneurs, and such experienced founders also have quicker access to VC and raise more money (Hsu 2007; Zhang 2011).

3.2.2 Results for the Spanish sample

Figure 4 shows the causal paths for the emergence of the outcome of the Spanish NTBFs. The result can be expressed as follows:

The first term of the solution (EDU*EXP*SIZE) shows a path in which the simultaneous presence of high levels of founders' work experience and the education of a large team of employees is sufficient to reach the outcome (obtaining the first round of financing). The second and third (EXP*SIZE*∼IP*∼ALL and EDU*SIZE*∼IP*∼ALL, respectively) terms show a similar path in which a high level of education or prior work experience of founders simultaneously with a large number of employees is sufficient in reaching the outcome even when the NTBFs have no intellectual properties and alliances. Finally, even for the last path, the solution shows a path that was empirically detected only in two cases and that considers the combination of alliances, big size, and intellectual properties unless a high level of founders' work experience (∼EXP*SIZE*IP*ALL).

The first path that leads to the outcome is the combination of a great experience and a high level of founders' education with a large number of employees at the time of the first funding. The NTBFs that show this path are in Madrid in 80% of the cases, with only one NTBF located in Barcelona. Most of them were founded around 2015 and only one in 2006. The investor type is Venture Capitalist in 60% of the cases, while Business Angels and Private Equity fund the remaining two NTBFs. 60% of the cases receive more than one round of funding, and the NTBFs grew all in value except NTBF 41, which decreased ( − 34%) from the first registered year (as reported in Table 10).

In the second path, the previous founders' experience is combined with big size and the absence of patents or alliances. Again, for Spain, the experience is a critical factor that leads to external investment. Experience combined with size ensures that the company is already structured on its own, and that patents or trademarks are not necessary, and not even the presence of research or sales agreement. This contrasts with the general idea that having a patent increases the hazard of obtaining financing (Bollazzi et al. 2019; Conti et al. 2013; Senyard et al. 2009). Patents can be seen as an exchange of information for protection (Long 2002). Inventors disclose the information comprising the invention in exchange for being able to exclude others from using the information in specific ways, such as reproducing the invention. The condition represented in this path demonstrates that rational inventors should seek patent rights only when the expected rents from the patent overcome the expected costs of disclosing information. We can conclude that it is not always true that a patent is strictly necessary to obtain the funding when there is an experienced founder with a large team who can give security to investors by being a competent person who has previously held a management role. The three NTBFs involved in this path are located in Madrid and financed by venture capitalists. Thus, we can consider that Venture Capitalists prefer experienced and larger teams with respect to other factors. Two of three NTBFs received more than one round of funding, where they were founded in 2015 and only one in 2011. As reported in Table 11, only one NTBF (43) decreased in value while the remaining two grew.

The third path (EDU*SIZE* ~ IP* ~ ALL) is very similar to the previous one: The only difference is that the variable Experience is replaced with the variable Education. Thus, large educated teams, with the absence of patents and alliances, lead to the obtainment of external funding.

In line with Engel and Keilbach (2007), we underline the importance of a high level of education: Firms whose managers have high educational degrees are more likely to obtain venture financing. This is not only linked with their knowledge because individuals who earned a master's degree or a Ph.D. increase performance in high-profit industries with high investment and low uncertainty environments.

Focusing on the NTBFs with this combination of signals, they are based in Barcelona and Catalonia. The companies have been founded in 2011 and 2015, respectively. The investors are Venture Capital and Private Equity. Both the NTBFs received more than one funding round, and they grew in value, as the total production value demonstrates (see Table 12).

The last path of the solution (~ EXP*SISE*IP*ALL) indicates that a combination of larger teams, some forms of protection of intellectual property, sales or research partnerships with other companies, and the absence of experienced founders gives a positive signal to the external investors. Comparing this path with the previous ones, it is still true that experience is one of the critical factors observed by external investors. However, when the founders do not have high managerial skills, investors rely on a structured NTBF with a patent and partnership with reputable companies for sale and research purposes. Hoenig and Henkel (2015) stated that when the firms' technologies are unknown, the importance values are 35% for patents, 38% for alliances, and 27% for the team experience. Following the authors, we can conclude that patents and alliances allow us to overshadow the absence of founders' experience. Two companies represent empirical evidence of this combination of causal conditions: They are located in Barcelona, and Venture Capitalists financed both. One NTBF was founded in 2001 and the other one in 2009: They are the older NTBFs in the sample. The NTBFs received more than one funding round, and only one NTBF grew in value, as presented in Table 13.

4 Discussion

This study examines conditions (education, experience, size, intellectual property, alliances) that act as signals for the chance of an NTBF to obtain a first financing round. After reviewing relevant literature on factors signaling access to the first financing round, a fsQCA model has been proposed to identify the combination of conditions causally linked to the outcome. Two propositions guided the research:

Proposition 1

Obtaining the first round of financing for NTBF companies is linked (in an asymmetric way) to the five selected signals (education, experience, size, intellectual property, and alliances).

Proposition 2

Different signals configurations (recipes) are equifinal to achieve the first round of financing for NTBF companies.

Based on a sample of 60 NTBFs from two moderate innovators countries (Portugal and Spain) ranked as the most profitable based on Crunchbase ranking, software simulations show that it exits a causal relationship between the factors analyzed as relevant and the number of financial resources raised during the first funding round from external investors. The main novelty of this research is the methodological approach, as a configurative approach has been applied differently from other studies relying on multiple regression analysis, where the net effects of single factors are isolated.

Four significant paths resulted from the analysis. In our results, variables must be considered as a combination rather than isolated.

According to the literature, the combination of education and experience representing the company's human capital has a positive relationship with external investment. Some scholars argue that the key determinants are the management team's skills regarding education and previous business experience (Bollazzi et al. 2019). Furthermore, having serial founders (who successfully run more than one company in the past) or founders linked with the university environment means not only being a competent person but also having a valuable network that can be exploited over time.

Moreover, results confirm that size matters (Cassar 2004; De Crescenzo et al. 2020; Der Foo et al. 2005). Size, combined with experience and education, underlines the hypothesis that this variable is a proxy for diversity and creativity more than in smaller teams (Der Foo et al. 2005). Thus, larger teams were associated with better evaluations when there was educational background diversity because they had more knowledge and different educational backgrounds to draw from.

Another characteristic that arises from this path is that when there is a combination of experience, education, and size, it does not matter whether a company possesses a patent or a trademark. This confirmed the results of Hoenig and Henkel (2015): Although they find comparatively high importance of patents for securing venture capital funding, they cannot identify a signaling effect of patents. According to them, VCs rely more on the team experience, as also happened in our research.

As highlighted in the literature section, sometimes, for NTBFs, a financing round is considered a key performance indicator better than revenue and profitability indicators. In a recent study, Yague-Perales et al. (2019) show that both revenue growth and positive profits are the top-ranking factors for attracting investors.

Studies based on venture capital transaction data show that the number of alliances a start-up owns positively relates to the amount of venture capital financing received (Baum and Silverman 2004; Greenberg 2013). The number and typology of this relationship are fundamental: Taking up the Hoenig and Henkel (2015) study, we focused on research and sales agreement. Thus, we can conclude that having a linkage with pilot customers and sales partners works as a quality signal that eventually can replace the presence of experienced founders. Entrepreneurs seek legitimacy to reduce the perceived risk of their activity by associating with or gaining explicit certification from well-regarded individuals and organizations (Hoang and Antoncic 2003).

Prior research demonstrates that having intellectual property rights positively affects the money received since patents help reduce information asymmetries (Bollazzi et al. 2019). In particular, patents act as a quality signal, reducing the cost of communicating private information to the market and providing entrepreneurs substantial advantages over their competitors. Along with the patents, other IP assets have been analyzed in the literature, like trademarks that considerably affect firms' market value (Sandner and Block 2011).

According to Zhou et al. (2016), our results show that patents' positive influence increases when the NTBF also has a trademark, but only in specific circumstances. Hoenig and Henkel (2015) find comparatively high importance of patents for securing VC funding, but not a signaling effect since they seem to rely on research alliances and partly on team experience as signals. This statement is partially shared since patents in this path are essential, but only when linked with research alliances (the predominant type of agreement of the NTBF involved). Indeed, unlike other studies, this research does not underline the possession of a patent as a proxy for obtaining funds; on the contrary, the variable appears more frequently negated. Overall, when intellectual property occurs, the human capital is not present or even negated. This can demonstrate that even if having a patent is not a critical signal of start-ups’ technological and marketing capabilities, but it can be very useful when there is no higher education or experience.

These statements are only the conclusion idea extracted from the results, but it is important to note that the combined effect of multiple factors, proposing combinations of causal conditions, generate results as a whole, not separately.

5 Conclusion

Our findings offer important insights into the signaling process theory. Scholars studying this theory have noted that the value of a signal is a function of its interpretation (e.g., Alsos and Ljunggren 2017; Connelly et al. 2011; Park and Mezias 2005).

Through the comprehensive assessment of the combination of signals in the context of NTBF financing, we can assert assumptions about the effectiveness of signaling to reduce information asymmetries and uncertainty (Vanacker et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2023).

This process appears to be complex in nature. Using a novel approach to the study of signaling theory and a configurative approach, we highlight different recipes (a combination of factors), leading to an outcome. As Colombo (2021) asserts, “an assessment of the interaction between different types of signals may be a fruitful direction for future studies; as recent evidence indicates, the combination of cues could contribute to the validity of signals (e.g., Cardon et al. 2017).” Our approach may help increasing the comprehension of the motivation behind the distance between investors and NTBFs.

The information provided by the empirical evidence based on a sample of successful NTBFs showed that actually exists a causal relationship between the factors of the proposed model and the number of financial resources raised during the first funding round from external investors. The analysis of sufficient conditions showed a causal relationship between the combination of considered signals and the number of financial resources raised during the first funding round from external investors.

We also offer an advance of our understanding of signaling consistency, that is, the simultaneous presence of multiple signals (Gao et al. 2008).

Until today, most research used regression-based techniques, where each variable is considered in isolation. Little is known about conflicting signals that can constitute a significant barrier to communication effectiveness (e.g., Fischer and Reuber 2007). A configurative approach, like fsQCA, is demonstrated to help for a better explanation of how these factors are combined in firms that obtained a first funding round. Instead of a single solution generalizable for all firms, this technique identifies different solutions that allow founders to find the first check or investor who will lead their round.

5.1 Implication for theory

In our aim, we offer advancement in methodological approach as an alternative tool to study the factors affecting the decisional process of NTBFs' financing. Moving from studies reporting analysis about factors influencing the achievement of financial rounds, we propose a model able to show the configurations of conditions in which X has a positive (negative) influence on Y, where the presence or absence of conditions may have both a positive influence on a given outcome when combined with other. Multi-regression analysis can only show the net effect of every single variable, independently by the presence or absence of any other given variables of the model. Reality shows how any insightful combination of conditions has an asymmetrical relationship with an outcome condition and not a symmetric one (Woodside 2013).

5.2 Implications for the practice

From a practical perspective, NTBF and new ventures, in general, could benefit from the results obtained to improve their resource acquisition. A company's ability to attract an investor's interest is strictly related to the signals in their communications with prospective investors. Relying on their own internal capabilities and strengths, they can be aware that, for example, a property right alone is not sufficient to be financed if not related to an external partnership, as it serves to compensate for the absence (eventually) of prior work experience. The size of the founding team is crucial. However, it should be combined at any time with other variables like education or prior work experience, which companies adopt as impression management behavior (Parhankangas and Ehrlich 2014), and must be applied (both or once per time) in combination with other variables (the size of the founding team). Founders can rely on different strategies to reach the first financing round, balancing different aspects of their new venture: searching for teammates with complementary knowledge and work experiences or emphasizing the need for an intellectual property strategy.

5.3 Limitations

Limitations of this work regard the sample since it is composed solely of young Iberic and IT NTBFs. Moreover, our model considers just 5 of the most cited signals that literature associates with obtaining financings. This may impact the generalization of our results. Therefore, cross-country and sector studies, as well as the testing of different signals, will represent the natural prosecution of our research.

References

Abbasian S, Yazdanfar D, Hedberg C (2014) The determinant of external financing at the start-up stage - empirical evidences from Swedish data. World Rev Entrepr Manag Sustain Devel 10:124–141. https://doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2014.058042

Alsos GA, Ljunggren E (2017) The role of gender in entrepreneur-investor relationships: a signaling theory approach. Entrep Theory Pract 41:567–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/etp.12226

Audretsch DB, Bönte W, Mahagaonkar P (2012) Financial signaling by innovative nascent ventures: the relevance of patents and prototypes. Res Policy 41:1407–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESPOL.2012.02.003

Azoulay P, Jones B, Kim D, Miranda J (2018) Research: the average age of a successful startup founder. Harv Bus Rev 45:115–187

Banerji D, Reimer T (2019) Startup founders and their LinkedIn connections: are well-connected entrepreneurs more successful? Comput Human Behav 90:46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.033

Bapna S (2019) Complementarity of signals in early-stage equity investment decisions: evidence from a randomized field experiment. Manag Sci 65:933–952. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2833

Baum JAC, Silverman BS (2004) Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. J Bus Ventur 19:411–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00038-7

Baum JAC, Calabrese T, Silverman B (2000) Don’t go it alone: alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strateg Manag J 21:267–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:33.0.CO;2-8

Beckman CM, Burton MD, O’Reilly C (2007a) Early teams: the impact of team demography on VC financing and going public. J Bus Ventur 22:147–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2006.02.001

Beckman CM, Burton MD, O’reilly C (2007b) Early teams: the impact of team demography on VC financing and going public B. J Bus Ventur 22:147–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.02.001

Bento N, Gianfrate G, Thoni MH (2019) Crowdfunding for sustainability ventures. J Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117751

Berge, ESC (2016) Is qualitative comparative analysis an emerging method?—structured literature review and bibliometric analysis of qca applications in business and management research. In: fgf studies in small business and entrepreneurship. pp 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27108-8_14

Bertoni F, Colombo MG, Grilli L (2011) Venture capital financing and the growth of high-tech start-ups: disentangling treatment from selection effects. Res Policy 40:1028–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.03.008

Bewaji T, Yang Q, Han Y (2015) Funding accessibility for minority entrepreneurs: an empirical analysis. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 22:716–733. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-08-2012-0099

Block JH, De Vries G, Schumann JH, Sandner P (2014) Trademarks and venture capital valuation. J Bus Ventur 29:525–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.006

Bocken NMP (2015) Sustainable venture capital - catalyst for sustainable start-up success? J Clean Prod 108:647–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.079

Bollazzi F, Risalvato G, Venezia C (2019) Asymmetric information and deal selection: evidence from the Italian venture capital market. Int Entrepr Manag J 15:721–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0539-y

Bugg-Levine A, Kogut B, Kulatilaka N (2012) A new approach to funding social enterprises. Unbundling societal benefits and financial returns can dramatically increase investment. Harv Bus Rev 90:118–123

Busenitz LW, Fiet JO, Moesel DD (2005) Signaling in venture capitalist—new venture team funding decisions: does it indicate long-term venture outcomes? Entrep Theory Pract 29:1–12

Calic G, Mosakowski E (2016) Kicking off social entrepreneurship: how a sustainability orientation influences crowdfunding success. J Manage Stud 53:738–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12201

Cardon MS, Mitteness C, Sudek R (2017) Motivational cues and angel investing: interactions among enthusiasm, preparedness, and commitment. Entrep Theory Pract 41:1057–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12255

Carpenter RE, Petersen BC (2002) Capital market imperfections, high-tech investment, and new equity financing. Economic Journal 112:F54–F72. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00683

Carpentier C, Suret J-M (2015) Angel group members’ decision process and rejection criteria: a longitudinal analysis. J Bus Ventur 30:808–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2015.04.002

Cassar G (2004) The financing of business start-ups. J Bus Ventur 19:261–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00029-6

Chen X-P, Yao X, Kotha S (2009) Entrepreneur passion and preparedness in business plan presentations: a persuasion analysis of venture capitalists’ funding decisions. Acad Manag J 52:199–214. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.36462018

Ciuchta MP, Letwin C, Stevenson R, McMahon S, Huvaj MN (2018) Betting on the coachable entrepreneur: signaling and social exchange in entrepreneurial pitches. Entrepr Theory Pract 42:860–885. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717725520

Colombo O (2021) The use of signals in new-venture financing: a review and research agenda. J Manag 47:237–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320911090

Colombo MG, Grilli L (2005b) Start-up size: the role of external financing. Econ Lett 88:243–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONLET.2005.02.018

Colombo MG, Grilli L (2010) On growth drivers of high-tech start-ups: exploring the role of founders’ human capital and venture capital. J Bus Ventur 25:610–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.01.005

Colombo MG, Franzoni C, Rossi-Lamastra C (2015) Internal social capital and the attraction of early contributions in crowdfunding. Entrep Theory Pract 39:75–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12118

Colombo MG, Grilli L (2005°) What makes a “ Gazelle ” in high-tech sectors ? A study on founders ’ human capital and access to external financing. In: 32th annual EARIE conference. Oporto, pp 1–31.

Connelly BL, Ketchen DJ, Slater SF (2011) Toward a “theoretical toolbox” for sustainability research in marketing. J Acad Mark Sci 39:86–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0199-0

Conti A, Thursby J, Thursby M (2013) Patents as signals for startup financing. J Ind Econ 61:592–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12025

Conti A, Thursby M, Rothaermel FT (2010) Show me what you have: signaling, angel and VC investments in technology startups. In: Academy of management 2010 annual meeting - dare to care: passion and compassion in management practice and research. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2010.54493650

Courtney C, Dutta S, Li Y (2017) Resolving Information asymmetry: signaling, endorsement, and crowdfunding success. Entrepr Theory Pract 41:265–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12267

Cronqvist L, Berg-Schlosser D (2009) Multi-value QCA (mvQCA). In: Configurational comparative methods: qualitative comparative analysis (qca) and related techniques. SAGE Publications, Inc., pp 69–86. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226569.n4

Dalle JM, den Besten M, Menon C (2017) Using Crunchbase for economic and managerial research. OECD Sci Technol Indus Work Pap. https://doi.org/10.1787/6c418d60-en

De Crescenzo V, Ribeiro-Soriano DE, Covin JG (2020) Exploring the viability of equity crowdfunding as a fundraising instrument: a configurational analysis of contingency factors that lead to crowdfunding success and failure. J Bus Res 115:348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.051

De Vries G, Pennings E, Block JH, Fisch C (2017) Trademark or patent? The effects of market concentration, customer type and venture capital financing on start-ups’ initial IP applications. Ind Innov 24:325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2016.1231607

de Lange DE (2019) A paradox of embedded agency: sustainable investors boundary bridging to emerging fields. J Clean Prod 226:50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.007

Der Foo M, Kam Wong P, Ong A (2005) Do others think you have a viable business idea? Team diversity and judges’ evaluation of ideas in a business plan competition. J Bus Ventur 20:385–402

Douglas E, Prentice C (2019) Innovation and profit motivations for social entrepreneurship: a fuzzy-set analysis. J Bus Res 99:69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2019.02.031

Drover W, Wood MS, Corbett AC (2018) Toward a cognitive view of signalling theory: individual attention and signal set interpretation. J Manage Stud 55:209–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12282

Duşa A (2007) User manual for the QCA(GUI) package in R. J Bus Res 60:576–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.002

Duşa A (2010) A mathematical approach to the Boolean minimization problem. Qual Quant 44:99–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-008-9183-x

Dusa, A., Dinkov, V., Baranovskiy, D., Quentin, E., Breck-McKye, J., Thiem, A., 2017. Package “QCA.” http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/QCA/QCA.pdf

Dy SM, Garg P, Nyberg D, Dawson PB, Pronovost PJ, Morlock L, Rubin H, Wu AW (2005) Critical pathway effectiveness: assessing the impact of patient, hospital care, and pathway characteristics using qualitative comparative analysis. Health Serv Res 40:499–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.0r370.x

Engel D, Keilbach M (2007) Firm-level implications of early stage venture capital investment - an empirical investigation. J Empir Finance 14:150–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2006.03.004

Fischer E, Reuber R (2007) The good, the bad, and the unfamiliar: the challenges of reputation formation facing new firms. Entrep Theory Pract 31:53–75

Frid CJ (2014) Acquiring financial resources to form new ventures: the impact of personal characteristics on organizational emergence. J Small Bus Entrep 27:323–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2015.1082895