Abstract

This study hypothesises that economic governance matters for economic performance; neglecting its role in creating positive synergies between macro- and microeconomic institutions has underlain significant coordination failures and costs. This study examines economic governance in the context of mutual feedback between macro-financial governance (FGV), macro-non-financial governance (NFGV), and micro-financial development (FND) in Germany in the period 1950–2019. The study uses an institutionalist approach, introducing two modes of economic governance based on institutional complementarities and tests its hypotheses using both an exhaustive structuralist analysis and a time-series quantitative technique based on the Autoregressive Distributed Lag cointegration model and the Vector Error Correction Mechanism. The study concludes that (i) the German model of economic governance based on the positive complementarities between FGV, NFGV and FND in the period 1950–1982 significantly enhanced real economic performance, that (ii) the fragmentation of the model became a key determinant of the country’s weak economic performance in the periods 1983–2019 and 1990–2019, and that (iii) the path-dependence of coordinational mechanisms and underlying institutional dynamics, though fragmented, prevented the genesis and embedding of an irrational exuberance in the country.

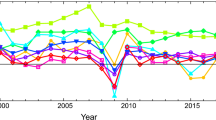

Source: Bundesbank (2020)

Source: Bundesbank (2020)

Source: Bundesbank (2020)

Source: Bundesbank (2021). *German contribution to Euro-Area M3

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

30 June 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-022-00359-4

Notes

Irrational exuberance caused finance sector to turn into a growth sector in itself (Beck 2012), underlying the de-linkage between growth and finance. Because (i) as a result of rapidly rising prices of financial assets, the profitability of financial investment outpaced the profitability of non-financial investment in the face of rapidly rising international competition in the market for goods and services, (ii) finance sector allocated an increasing proportion of available financial funds to short-run speculative investment rather than to productive industrial investment with deepening financial deregulation and the introduction of sophisticated financial technologies, and (iii) non-financial investors started using an increasing proportion of their financial resources for financial investment rather than for non-financial investment (Palley 2013).

Synergy-creating governance is neither a ‘hieararchy’ nor ‘a centrally-planned model’ in Hayekian sense. It denotes that policy coordination driven by positive complementarities can mediate a stronger and more sustainable economic performance.

There are five points that should be clarified in understanding this intermediary role of institutions. First, the nature and the direction of the actors’ preferences are expressed as policy choices, rather than institutions themselves. For example, governments can increase or decrease the size or quantity of their investment in the market for goods and services. Second, by increasing or decreasing the size of investment, public investment policy determines the scale and direction of the intermediary role of investment or how investment is used in enforcing a policy choice. Third, investment as an institution here intermediates the relationship between the policy choice and the structure affected by the policy—that is, the market for goods and services. Fourth, macroeconomic governance is the collective ordering of micro-macro-policy choices in using the financial and non-financial institutions illustrated in Fig. 1. Five, macro-economic indicators illustrate not the macroeconomic institutions themselves such as investment, consumption, and trade but the quantity of these institutions or the change in their quantities in time.

As there is a well-established literature on finance-growth nexus, we did not delve into its details for saving space in this paper. See Cournède, B., & Denk, O. (2015). Finance and economic growth in OECD and G20 countries. Available at SSRN 2649935. for a detailed documentation of (i) the varieties of positive and negative relationships between growth and finance and (ii) the relevant literature.

Hellwig (2018: 2) calculates this amount by “adding up numbers that have been publicly given for various institutions”, as precise data on fiscal costs were not available.

Output gap in this period amounted to −0.4 percent of the potential output on an average according to IMF’s calculation (see IMF, 2021), which is much higher than AMECO’s calculation.

F-test estimates two types of cointegration relationships simultaneously. First is the joint relationships between dependent and all independent variables. Second is the separate long-run relationship between dependent and each independent variable. That F-test is statistically significant implies the first type of cointegration relationship for all cases but this does not require that there be the second type of cointegration relationship as well. We are looking at the cointegration coefficients to infer the existence or the absence of second type of cointegration relationship.

References

Allen CS (2005) Ordo-liberalism trumps Keynesianism: economic policy in the federal republic of Germany and the EU. Monetary union in crisis. Springer, New York, pp 199–221

Allen CS (2010) Ideas, institutions, and organised capitalism: The German model of political economy twenty years after unification. German Polit Soc 28(2):130–150

Antonios A (2010) Stock market and economic growth: an empirical analysis for Germany. Bus Econ J 1:1–12

Aoki M (1994) The contingent governance teams: Analysis of institutional complementarity. Int Econ Rev 35:657–676

Arcand JL, Berkes E, Panizza U (2012) Too much finance?. IMF Working Paper 12/161.

Baldwin R (2006) The Euro's trade effects. ECB Working Paper No. 594. https://ssrn.com/abstract=886260.

Beck T (2012) Finance and growth–lessons from the literature and the recent crisis. LSE Growth Comm 3:1–6

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A (2009) Financial institutions and markets across countries and over time: data and analysis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4943.

Behr P, Schmidt RH (2015). The German banking system: Characteristics and challenges. Geothe University SAFE Working Paper, No: 32, https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/129081

Bencivenga VR, Smith BD (1991) Financial intermediation and endogenous growth. Rev Econ Stud 58:195–209

Berlemann M, Wesselhöft JE (2012) Total factor productivity in German regions. Cesifo Forum 13(2):58–65

Bernanke B, Mishkin F (1992) Central bank behavior and the strategy of monetary policy: observations from six industrialized countries. NBER Macroecon Ann 7:183–228

Beyer A, Gaspar V, Gerberding C, Issing O (2013) Opting out of the great inflation: German monetary policy after the breakdown of bretton woods. The great inflation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 301–356

Bibow J (2013) At the crossroads: the Euro and its central bank guardian. Cambridge J Econ 37:609–626

Blanchard O (2018) On the future of macroeconomic models. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 34(1–2):43–54

Bluhm K, Martens B (2009) Recomposed institutions: Smaller firms’ strategies, shareholder-value orientation and bank relationships in Germany. Soc Econ Rev 7(4):585–604

Boyer R (2000) Is a finance-led growth regime a viable alternative to Fordism? A preliminary analysis. Econ Soc 29(19):111–145

Braun HJ (2010) The German economy in the twentieth century (Routledge Revivals): The German Reich and the Federal Republic. Routledge, London

Bundesbank (1995). The monetary policy of the Bundesbank. Frankfurt am Main.

Bundesbank (2018) The Monetary Policy of the Bundesbank. Bundesbank Publications. https://www.bundesbank.de/en/publications/bundesbank/the-monetary-policy-of-the-bundesbank-702946. Accessed on 09 Jan 2018.

Bundesbank (2019) Financial accounts. Bundesbank Statistics. https://www.bundesbank.de/en/statistics/macroeconomic-accounting-systems/financial-accounts/financial-accounts-792676. Accessed on 11 Dec 2019.

Bundesbank (2020) Macroeconomic and financial statistics. Bundesbank Statistiken. https://www.bundesbank.de/de/statistiken/zeitreihen-datenbanken, Accessed on 9 March 2020.

Burda MC, Severgnini B (2018) Total factor productivity convergence in German states since reunification: evidence and explanations. J Comp Econ 46(1):192–211

Colander D, Goldberg M, Haas A, Juselius K, Kirman A, Lux T, Sloth B (2009) The financial crisis and the systemic failure of the economics profession. Crit Rev 21(2–3):249–267

Corneo G (2004) The rise and likely fall of the German income tax, 1958–2005. Cesifo Econ Stud 51(1):159–186

Cournède B, Denk O (2015) Finance and economic growth in OECD and G20 countries. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2649935

Deeg R (2007) Complementarity and institutional change in capitalist systems. J Eur Public Policy 14(4):611–630

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2001) Financial structure and economic growth. The MIT Press, Massachusets

Detzer D, Dodig N, Evans T, Hein E, Herr H, Prante FJ (2017) The German financial system and the financial and economic crisis. Springer, Cham

Dustmann C, Fitzenberger B, Schönberg U, Spitz-Oener A (2014) From sick man of Europe to economic superstar. J Econ Perspect 28(1):167–188

Düwel C, Frey R and Lipponer A (2011) Cross-border bank lending, risk aversion and the financial crisis. Duetsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper Series 29.

Dyson K (1989) Economic policy. Developments in West German Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 148–167

Eurostat (2020) Economy and finance statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. Accessed on 05 May 2020.

Elsas R, Krahnen J (2004) Universal banks and relationships with firms. In: Krahnen JP, Schmidt RH (eds) The German Financial System. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 197–232

European Commission Economic and Financial Affairs (2020). ‘AMECO Database’. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/ameco/user/serie/SelectSerie.cfm. Accessed on 15 April 2020

European Commission (2007) Country study: Raising Germany’s growth potential. European Economy Occasional Papers 28, Brussels.

European Commission, IMF, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, UN, World Bank (2009) System of national accounts 2008. New York.

European Commission (2014) Macroeconomic imbalances: Germany. Brussels.

European Commission: DG Economic and Financial Affairs (2002) Germany’s Growth Performance in the 1990s. Economic Papers 170, Brussels.

Felbermayr G, Fuest C and Wollmershäuser T (2017) The German current account surplus: where does it come from, is it harmful and should Germany do something about it? IFO Institute: Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich, MunichEconPol Policy Report No. 02.

Fischer KH, Pfeil C (2004) Regulation and competition in German banking. In: Krahnen J, Schmidt RH (eds) The German Financial System. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 291–349

Fliegstein N (2001) The architecture of markets. Princeton University, Princeton, An economic sociology of twenty-first-century capital societies

GESIS Database (2020) Historical Statistics. https://www.gesis.org/home. Accessed on 10 Feb 2020.

Glaessner GJ (2005) German Democracy: from post-World War II to the present day. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Greenwood J, Boyan J (1990) Financial development, growth, and distribution of income. J Polit Econ 5:1076–1108

Hayek FA (2012) Law, legislation and liberty, volume 2: The mirage of social justice (Vol. 2). University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Hein E, Truger A (2007) Macroeconomic policies, wage developments and Germany’s stagnation. In: Hölscher J (ed) Germany’s Economic Performance from Unification to Eurozone. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 143–166

Hellwig, Martin (2018) “Germany and the Financial Crises 2007–2017”. https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/759000/c7f985a2adbdf1c54ba385406a4b5294/mL/2018-06-15-stockholm-06-paper-hellwig-data.pdf, Accessed on 04 March 2022.

Hetzel RL (2002) German monetary history in the second half of the twentieth century: from the deutsche mark to the Euro. FRB Richmond Econ Quart 88(2):29–64

Höpner M, Spielau A (2018) Better than the Euro? The European monetary system (1979–1998). New Polit Econ 23(2):160–173

IMF (2012) Global financial stability report, October 2012. https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/books/082/12744-9781616353902-en/12744-9781616353902-en-book.xml. Accessed on 02 March 2022.

IMF (2021) ‘Global Economic Outlook Database’. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases. Accessed on 05 March 2022.

Issing O (1997) Monetary targeting in Germany: the stability of monetary policy and of the monetary system. J Monet Econ 39:67–79

Jackson G (2012) The trajectory of institutional change in Germany, 1979–2009. J Eur Public Policy 19(8):1146–1167

Jappelli T, Pagano M (1994) Saving, growth, and liquidity constraints. Quart J Econ 109(1):83–109

Jolliffe IT (2002) Principal component analysis. Springer, New York

Kaltenthaler K (2005) The Bundesbank and the formation of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy. German Polit 14(3):297–314

Keck O (1993) The national system for technical innovation in Germany. National innovation systems: A comparative analysis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship, pp 115–157. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1496195

Kloß M, Lehmann R, Ragnitz J, Untiedt G (2012) Auswirkungen veränderter Transferzahlungen auf die wirtschaftliche Leistungsfähigkeit der ostdeutschen Länder, ifo Dresden Studien, No. 63, ISBN 978–3–88512–524–2, ifo Institut, Niederlassung Dresden, Dresden.

Kreile M (1977) West Germany: the dynamics of expansion. Int Organ 31(4):775–808

Lane C (2003) Changes in corporate governance of German corporations: convergence to the Anglo-American model? Compet Change 7(2–3):79–100

Law SH, Singh N (2014) Does too much finance harm economic growth? J Bank Finan 41:30–44

Lawson T (2013) What is this ‘school’ called neoclassical economics? Camb J Econ 37(5):947–983

Leaman J (1988) The political economy of West Germany, 1945–1985. Houndmills McMillan, Basingstoke.

Levine R, Zervos S (1996) Stock market development and long-run growth. World Bank Econ Rev 10:323–339

Lucas REJR (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. J Monet Econ 22:3–42

Micossi S (2015) The monetary policy of the European Central Bank, 2002–2015. CEPS Special Report 109.

OECD (2018) Economic surveys: Germany, Paris.

OECD (2021) Economic outlook database statistical annex. https://www.oecd.org/economy/outlook/statistical-annex/. Accessed on 02 March 2022.

Padgett S (2003) Political economy: The German under stress. In: Padgett S, Paterson WE, Smith G (eds) New developments in German politics 3. Duke University Press, Durham, pp 121–142

Palley TI (2013) Financialization: what it is and why it matters. In: Financialization. Springer, pp 17–40

PENN World Tables (2021) PWT 10.0. https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/productivity/pwt/?lang=en. Accessed on 09 Sept 2021.

Pesaran MH, Shin Y (1999) An autogregressive distributed lab model in approach to cointegration analysis. In: Strom S (ed) Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th century: the Ragnara Frisch Centennial Symposium. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 371–413

Pesaran M, Shin Y (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Economet 16(3):289–326

Peters B, Rammer C (2013) Innovation panel surveys in Germany. Handbook of innovation indicators and measurement. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, Northampton, pp 135–177

Romer CD, Romer DH (2013) The most dangerous idea in federal reserve history: Monetary policy doesn’t matter. Am Econ Rev 103(3):55–60

Romer D (2011) What have we learned about fiscal policy from the crisis?, https://www.imf.org/external/np/seminars/eng/2011/res/pdf/DR3presentation.pdf. Accessed on 10 Feb 2019.

Saint-Paul G (1992) Technological choice, financial markets and economic development. Eur Econ Rev 36(4):763–781

Salvatore D (2020) Growth and trade in the United States and the world economy: overview. J Policy Model 42(4):750–759

Scharpf FW (2015) Is there a successful “German Model”? In: Unger B (ed) The German model: seen by its neighbours. SE Publishing, pp 87–104

Shiller RJ (2015) Irrational exuberance. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Sommariva A, Tullio G (1987) German macroeconomic history, 1880–1979. Martin Press, New York, St

Stiglitz J (2012) Macroeconomics, monetary policy, and the crisis. In: Blanchard O, Romer D, Spence AM, Stiglitz JE (eds) In the wake of the crisis: leading economists reassess economic policy. MIT Press, Massachusetts, pp 31–42

Storm S, Naastepad CWM (2015) Crisis and recovery in the German economy: the real lessons. Struct Change Econ Dyn 32:11–24

Streeck W (1997) German capitalism: does it exist? Can it survive? New Polit Econ 2(2):237–256

Streeck W (2009) Reforming capitalism: institutional change in Germany political economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Tobin J (1981) On the efficiency of financial system. https://economicsociologydotorg.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/tobin-on-the-efficiency-of-the-financialsystem.pdf. Accessed on 21 Sept 2021.

Williamson, O E (2000) The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. J Econ Literat 38(3: 595–613.

World Bank (2021) World development indicators database. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worlddevelopment-indicators#. Accessed on 30 September 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Appendix 1

1. PCA for NFGV (Annual, 1950–2019)

Eigenvalues: (Sum = 5, Average = 1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number | Value | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative value | Cumulative proportion |

1 | 4.950702 | 4.917328 | 0.9901 | 4.950702 | 0.9901 |

2 | 0.033375 | 0.023097 | 0.0067 | 4.984077 | 0.9968 |

3 | 0.010278 | 0.005250 | 0.0021 | 4.994355 | 0.9989 |

4 | 0.005027 | 0.004409 | 0.0010 | 4.999382 | 0.9999 |

5 | 0.000618 | – | 0.0001 | 5.000000 | 1.0000 |

2. PCA for FGV (Annual, 1950–2019)

Eigenvalues: (Sum = 4, Average = 1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number | Value | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative value | Cumulative proportion |

1 | 3.967095 | 3.947157 | 0.9918 | 3.967095 | 0.9918 |

2 | 0.019938 | 0.010432 | 0.0050 | 3.987033 | 0.9968 |

3 | 0.009506 | 0.006046 | 0.0024 | 3.996540 | 0.9991 |

4 | 0.003460 | – | 0.0009 | 4.000000 | 1.0000 |

3. PCA for NFGV (Quarterly, 2008Q1–2019Q4)

Eigenvalues: (Sum = 5, Average = 1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number | Value | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative value | Cumulative proportion |

1 | 4.112832 | 3.422619 | 0.8226 | 4.112832 | 0.8226 |

2 | 0.690213 | 0.539033 | 0.1380 | 4.803045 | 0.9606 |

3 | 0.151180 | 0.117529 | 0.0302 | 4.954224 | 0.9908 |

4 | 0.033650 | 0.021525 | 0.0067 | 4.987875 | 0.9976 |

5 | 0.012125 | – | 0.0024 | 5.000000 | 1.0000 |

1.2 Appendix 2: The plots of CUSUM and CUSUMSQ stability tests

1950–1982

Model 1.1.

Model 1.2.

Model 1.3

1950–1989

Model 1.1.

Model 1.2.

Model 1.3.

1983–2019

Model 1.1.

Model 1.2.

Model 1.3.

Model 2.1.

Model 2.2.

Model 2.3.

1990–2019

Model 1.1.

Model 1.2.

Model 1.3.

Model 2.1.

Model 2.2.

Model 2.3.

2008Q1-2019Q1

Model 3.1.

Model 3.2.

Model 3.3.

Model 4.1.

Model 4.2.

Model 4.3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akan, T., Solle, T. Do macroeconomic and financial governance matter? Evidence from Germany, 1950–2019. J Econ Interact Coord 17, 993–1045 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-022-00356-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-022-00356-7

Keywords

- Macroeconomic governance

- Financial governance

- Financial development

- Cointegration

- German model

- Institutions