Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to compare the life cycle energy and costs derived from the production and occupation of social interest housing models located in two different types of neighborhoods: compact and sprawling. Two neighborhood development alternatives in Mexico City were established and evaluated including the potential impacts analysis of the built environment/infrastructure and the commuting of the occupants.

Methods

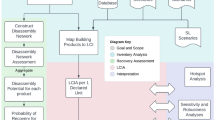

The study includes the conventional phases of a building life cycle (LC)—preoccupation, occupation, and post-occupation—but it was expanded to include a fourth phase, “occupant transportation,” to cover the commuting potential impacts. The methodology consists of four main stages: (1) definition of function, functional unit, and scope; (2) data collection—divided in three main steps: architectural, land costs and transformations, and commuting data; (3) impact assessment—we used software SimaPro v8.0.1 to manage the LC inventory data; and (4) interpretation of results and sensitivity analysis.

Results and discussion

In the preoccupation phase, the sprawling neighborhood cell (NC) cumulative energy demand (CED) is 30 % larger than the compact NC ones. Regarding the LC costs, land costs strongly impact the compact NC, but when aggregated in the preoccupation phase, the LC costs for the sprawling NC are only 14 % above those of the compact NC. For the occupation phase, results show that the compact NC has lower CED (by 10 %) and LC costs (16 %) than the sprawling NC. The occupant transportation phase plays a highly important role, since it represents up to 28 % of total LC CED and up to 54 % of total LC costs. This phase affects significantly the sprawling NC, which has a 25 % higher CED and doubles LC costs, when compared with the compact NC. Post-occupation phase contributes just in a small proportion of the total CED and LC costs for both NC, since it accounts for 3 % or less of the total energy and LC costs. Overall results show that the compact NC has lower CED and LC costs than the sprawling NC.

Conclusions

The results show that occupant transportation phase plays a highly important role in the neighborhood performance. Neighborhood development assessment should consider a number of variables beyond CED and costs. However, in order to improve the sector’s energy efficiency and household’s economy, we recommend to consider house location as it can be as important as other energy or cost-reduction actions in neighborhood development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this study, we refer to Mexico City as a synonym of the Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico, which according to CONAPO (CONAPO 2012) includes selected municipalities of the states of Hidalgo, Mexico, and Mexico City (formerly known as Federal District).

In multimode trips, commuters use more than one transportation mode, for example, walking, bus, metro, walking.

According to SHF, the dataset (SHF 2013) includes information reported by all the valuation units and is not liable for its content or the use that is given to it.

Abbreviations

- CMM:

-

Mario Molina Center

- CO2eq:

-

Carbon dioxide equivalent

- LC:

-

Life cycle

- LCA:

-

Life cycle analysis

- NC:

-

Neighborhood cell

- USD:

-

United States dollars

References

Arena AP (2000) Spreading life-cycle assessment to developing countries. J Ind Ecol 4(3):3–6, doi:10.1162/108819800300106348

Bimsa Reports. Activecost Universe, Costos de construcción 2013. México, 2013

Cabeza LF, Rincón L, Vilariño V, Pérez G, Castell A (2014) Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) of buildings and the building sector: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 29:394–416

CDMX (2015) Sistema de transporte colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro. Gobierno del Distrito Federal. http://www.metro.df.gob.mx/. Accessed August 2015

CDMX (2013) Metrobús, Ciudad de México. Gobierno del Distrito Federal. http://www.metrobus.df.gob.mx/. Accessed August 2015

Cerón-Palma I, Sanyé-Mengual E, Oliver-Solà J, Montero J-I, Ponce-Caballero C, Rieradevall J (2013) Towards a green sustainable strategy for social neighbourhoods in Latin America: case from social housing in Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. Habitat Int 38:47–56

Chavez-Baeza C, Sheinbaum-Pardo C (2014) Sustainable passenger road transport scenarios to reduce fuel consumption, air pollutants and GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Energy 66(2):624–634

CMM (2012) Evaluación de la sustentabilidad de la vivienda en México. Centro Mario Molina para Estudios Estratégicos sobre Energía y Medio Ambiente, A.C, Mexico City, Mexico

CMM (2014) Sustainable housing: location as a strategic factor. Centro Mario Molina para Estudios Estratégicos sobre Energía y Medio Ambiente, A.C, Mexico City, Mexico

CMM (2015) Urban planning scenarios: Mexico City metropolitan area. Centro Mario Molina para Estudios Estratégicos sobre Energía y Medio Ambiente, A.C, Mexico City, Mexico

Cole RJ, Kernan PC (1996) Life-cycle energy use in office buildings. Build Environ 31(4):307–317

CONAPO (2010) Proyecciones de la población 2010-2050. http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Proyecciones_Datos Accessed 25 May 2015

CONAPO (2012) Delimitación de las Zonas Metropolitanas de México. http://www.conapo.gob.mx/en/CONAPO/Zonas_metropolitanas_2010 Accessed 23 Mar 2016

Cruz-Salas MV, Castillo JA, Huelsz G (2014) Experimental study on natural ventilation of a room with a windward window and different windexchangers. Energ Buildings 84:458–465

De Buen O (2009) Greenhouse gas emission baselines and reduction potentials from buildings in Mexico (a discussion document). UNEP DTIE Sustainable Consumption & Production Branch, Paris, France

Famuyibo AA, Duffy A, Strachan P (2013) Achieving a holistic view of the life cycle performance of existing dwellings. Build Environ 70(2):90–101

Frischknecht R, Jungbluth N, Althaus H-J, Doka G, Dones R, Heck T, Hellweg S, Hischier R, Nemecek T, Rebitzer G, Spielmann M (2005) The ecoinvent database: overview and methodological framework. International Int J Life Cycle Assess 10:3–9

Fuller RJ, Crawford RH (2011) Impact of past and future residential housing development patterns on energy demand and related emissions. J Hous Built Environ 26(2):165–183

Futcher JA, Mills G (2013) The role of urban form as an energy management parameter. Energ Policy 53:218–228

Blengini GA, Di Carlo T (2010) The changing role of life cycle phases, subsystems and materials in the LCA of low energy buildings. Energ Buildings 42:869–880

Guerra E (2014) Mexico City’s suburban land use and transit connection: the effects of the line B metro expansion. Transport Policy 32:105–114

Güereca LP, Ochoa R, Gilbert H, Suppen N (2015) Life cycle assessment in Mexico: overview of development and implementation. The International Int J Life Cycle Assess 20:311–317

Hernández-Moreno A, Mugica-Álvarez V (2013) Vehicular fleets forecasting to project pollutant emissions: Mexico City metropolitan area case. Transport Policy 27:189–199

INEGI (2010) Censo de población y vivienda 2010. Total de viviendas habitadas. Estados Unidos Mexicanos. http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mexicocifras/. Accessed 1 June 2015

INEGI (2014a) Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Aguascalientes, México. http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mapa/denue/

INEGI (2014b) Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares (ENIGH) 2014. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Aguascalientes, México. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/encuestas/hogares/regulares/enigh/enigh2014/tradicional/default.aspx

Iyer-Raniga U, Wong JPC (2012) Evaluation of whole life cycle assessment for heritage buildings in Australia. Build Environ 47:138–149

Karimpour M, Belusko M, Xing K, Bruno F (2014) Minimising the life cycle energy of buildings: review and analysis. Build Environ 73:106–114

Kofoworola OF, Gheewala SH (2009) Life cycle energy assessment of a typical office building in Thailand. Energ Buildings 41(10):1076–1083

Krizek KJ (2003) Residential relocation and changes in urban travel: does neighborhood-scale urban form matter? J Am Plann Assoc 69(3):265–281

Llatas C (2011) A model for quantifying construction waste in projects according to the European waste list. Waste Manage 31(6):1261–1276

Madlener R, Sunak Y (2011) Impacts of urbanization on urban structures and energy demand: what can we learn for urban energy planning and urbanization management? SCS 1(1):45–53. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2010.08.006

Norman J, Maclean HL, Asce M, Kennedy CA (2006) Comparing high and low residential density : life-cycle analysis of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. J Urban Plann Dev 1(10):10–21

Ochoa R, Hernández A, Garfias M (2015) Life cycle energy and costs of sprawling and compact neighborhoods. VI International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment (CILCA). Lima, Peru

Oropeza-Perez I, Ostergaard PA (2014) Energy saving potential of utilizing natural ventilation under warm conditions—a case study of Mexico. Appl Energ 130:20–32

Parry IWH, Timilsina GR (2009) Pricing Externalities from Passenger Transportation in Mexico City. World Bank Working Papers

PGL (2011) The greenest building: quantifying the environmental value of building reuse. Preservation Green Lab, National Trust for Historic Preservation. http://www.preservationnation.org/information-center/sustainable-communities/green-lab/lca/The_Greenest_Building_lowres.pdf

Pilz H, Brandt B, Fehringer R (2010) The impact of plastics on life cycle energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. Denkstatt, Vienna, Austria

R Development Core Team (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. <www.R-project.org>. Accessed 03.2015

Ramesh T, Prakash R, Shukla KK (2010) Life cycle energy analysis of buildings: an overview. Energ Buildings 42(10):1592–1600

Reyes-Sanchez A (2015) Beyond just light bulbs: the mitigation of greenhouse gas emission in the housing sector in Mexico City. City Proc. ISSST. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.1512512 v3

Rosas-Flores JA, Morillón Gálvez D (2010) What goes up: recent trends in Mexican residential energy use. Energy 35(6):2596–2602. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2010.01.015

Rosas J, Sheinbaum C, Morillon D (2010) The structure of household energy consumption and related CO2 emissions by income group in Mexico. Energy Sustain Dev 14:127–133

Rosas-Flores J, Rosas-Flores D, Gálvez D (2011) Saturation, energy consumption, CO2 emission and energy efficiency from urban and rural households appliances in Mexico. Energ Buildings 43(1):10–18

Rosas-Flores JA, Morillón Gálvez D, Fernández Zayas JL (2010) Inequality in the distribution of expense allocated to the main energy fuels for Mexican households: 1968–2006. Energ Econ 32(5):960–966. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2010.02.007

SEDATU (2014) Programa Nacional de Desarrollo Urbano 2014-2018, 2014. http://www.sedatu.gob.mx/sraweb/datastore/programas/2014/PNDU/PROGRAMA_Nacional_de_Desarrollo_Urbano_2014-2018.pdf

SEDEMA (2015) ¿Cuánto cuesta deshacerse de la basura? www.sedema.df.gob.mx/. Accessed August 2015

SEDEMA (2014) Programa de Acción Climática de la Ciudad de México 2014-2020. http://www.sedema.df.gob.mx/sedema/index.php/temas-ambientales/cambio-climatico. Accessed April 2015

SENER (2015) Sistema de Información Energética. http://sie.energia.gob.mx/. Accessed 2014

Sharma A, Saxena A, Sethi M, Shree V (2011) Life cycle assessment of buildings: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 15(1):871–875

SHF (2013) Estadísticas de vivienda. http://www.shf.gob.mx/estadisticas/EstadVivInformaAvaluos/. Accessed June 2015

UNEP (2004) Why take a life cycle approach? United Nations Environment Programme. Division of Technology, Industry and Economics Productions and Consumption Branch. Paris, France

Van Ooteghem K, Xu L (2012) The life-cycle assessment of a single-storey retail building in Canada. Build Environ 49:212–226

Wallhagen M, Glaumann M, Malmqvist T (2011) Basic building life cycle calculations to decrease contribution to climate change—case study on an office building in Sweden. Build Environ 46:1863–1871

Wang X, Chen D, Ren Z (2010) Assessment of climate change impact on residential building heating and cooling energy requirement in Australia. Build Environ 45(7):1663–1682

Weidema BP, Bauer Ch, Hischier R, Mutel Ch, Nemecek T, Reinhard J, Vadenbo CO, Wernet G (2013) The ecoinvent database: overview and methodology, data quality guideline for the ecoinvent database version 3, from www.ecoinvent.org

Xamán J, Hernández-López I, Alvarado-Juárez R, Hernández-Pérez I, Álvarez G, Chávez Y (2015) Pseudo transient numerical study of an earth-to-air heat exchanger for different climates of México. Energ Buildings 99:273–283

Yin Y, Mizokami S, Maruyama T (2013) An analysis of the influence of urban form on energy consumption by individual consumption behaviors from a microeconomic viewpoint. Energ Policy 61:909–919

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) who provided funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Ramzy Kahhat

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(XLSX 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ochoa Sosa, R., Hernández Espinoza, A., Garfias Royo, M. et al. Life cycle energy and costs of sprawling and compact neighborhoods. Int J Life Cycle Assess 22, 618–627 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1100-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1100-2