Abstract

Venture capital firms play a crucial role in entrepreneurial success. Similarly, due to their experience and expertise, serial entrepreneurs have been shown to have positive but diminishing effects on the firms with which they are involved. However, what is the effect of mixing serial entrepreneurs with venture capitalists? This study advances our knowledge of venture capitalists and serial entrepreneurs by adopting a human capital-driven multi-agency theoretical framework for their interplay on performance and process issues. Counterintuitively, we find that serial entrepreneur involvement correlates with lower IPO values, but consistent with MAT theory, it lengthens the time to IPO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The initial public offering (IPO) is widely recognized as a significant event for entrepreneurial firms and often a pivotal strategic point. Many studies have modeled the “success” of an IPO due to factors centered around the involvement of private investment stakeholders, such as venture capitalists, who bring expertise as well as capital, underwriters, and the firm’s founder (e.g., Jain & Kini, 2000; Mousa & Wales, 2012). However, this raises an interesting question, who is driving the IPO process—is it the venture capitalists or the firm?

The importance of venture capitalists is well documented as they bring financial resources and expertise to firms. Early research by Bygrave and Stein (1990) found positive returns between venture capitalist (VC) involvement and IPO returns. Subsequent work showed that VC involvement increased IPO firm survival rates (Jain & Kini, 2000) and that top VC firms, when paired with top underwriters, resulted in higher market returns to IPOs (Lange et al., 2001). However, while intuitively appealing, this finding has only sometimes shown up in higher firm share performance (Kutsuna et al., 2000).

Simultaneously, we see the rise of individuals who undertake to start several firms – so-called serial or habitual—entrepreneurs (MacMillan et al., 1989). Given the high failure rate of new ventures, this is often an entrepreneurial necessity. However, serial entrepreneurs learn and develop social networks and expertise to help them in future ventures (Semrau & Werner, 2014; Zang, 2011). However, despite its intuitive appeal, early research showed that the track record of serial entrepreneurs was no better than that of novices (Birley & Westhead, 1994). Possibly because of the large number of factors that could influence the success or failure of new ventures, subsequent research showed that while there were significant differences in founders, such as how they acquired their multiple firms, if they ran them in succession or simultaneously, and other sources of heterogeneity, there is little evidence that serial founders financially outperform novices (Wright et al., 1997; Westhead & Wright, 1998; Gartner et al., 1998). More recent work, however, has shown positive learning effects for serial entrepreneurs (Politis, 2008), though it exhibits regression to the mean (Parker, 2013). Yet, the research on serial entrepreneurs is still scant (Lin et al., 2019).

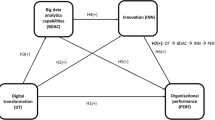

We explore the research question of how these two stakeholders, venture capitalists, and serial entrepreneurs, interact to affect the timing and results of the IPO process. To model this relationship, we apply multiple agency theory (MAT). MAT extends agency theory to account for the fact that a principal sometimes relies on multiple agents, each of which have their own interests that are not perfectly aligned (Hoskisson et al., 2013). Therefore, MAT considers elements such as dual identity – where the agent serves multiple principals, the existence of transcending relationships between agents; and different time horizons (Hoskisson et al., 2013). Multiple agents are present in an IPO context, specifically – the firm’s founder and insiders, the venture capitalists, and the underwriters (Hoskisson et al., 2013). The venture capitalists are especially important under MAT as they serve both the focal IPO firm and their investors as agents while having an ongoing relationship with underwriters and potentially a different time horizon than the firm founders.

Therefore, this study makes several contributions. First, we apply the lens of MAT to both the IPO process and IPO performance. Second, we are exploring the role and importance of serial entrepreneurs in a new firm’s time to IPO. Third, we extend the time to IPO literature by examining the interaction between serial entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. Fourth, we answer a call to add to the serial entrepreneurship literature (Ucbasaran et al., 2003; Westhead & Wright, 1998) an essential dimension of entrepreneurship that has not received as much research as it deserves. Finally, we consider two dependent variables—value and time to IPO. While examining two dependent variables in a paper is a little unusual, it is necessary here because they are both salient to both the IPO firm and the venture capitalists and yet offer the potential for the divergence of interests between them. We expect congruence on value and incongruence on time to IPO. Therefore, exploring two dependent variables allows us to fully explore the application of MAT to the IPO process with these actors.

Firm valuation (a.k.a. capital raised at IPO) is an essential and important dependent variable. It focuses explicitly on the check the entrepreneurs get to take home and the firm’s funding base in the future. It is of more long-term consequence to the firm than underpricing. While underpricing money “left on the table” is regrettable, the IPO's size will signal viability and provide an essential resource base for the firm. While few in number, past work on valuation has studied a wide range of issues, from the impact of firm-specific capabilities (Deeds et al., 1997) or top management team (TMT) heterogeneity to the effect that slack resources might have on new ventures at time of IPO (Mousa & Reed, 2013). So clearly, both venture capitalists and firms share an interest in maximizing the value of the IPO. However, there is an area where their interests do not align—time.

The time from incorporation to IPO is very relevant for managers and investors and is where the application of MAT offers insights. An IPO is a significant event in the life of any firm where the firm ceases to exist as a private company and joins the world of publicly traded firms. Given the lack of other conventional measures for young firms, time to IPO can be a useful outcome measure (Chang, 2004; Deeds et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2011). Investors are known to consider time as a criterion for the attractiveness of a particular investment, and VCs generally consider the speed by which a new firm goes public when calculating the return on investment (Shepherd & Zacharakis, 2001). Venture capitalists prefer a shorter gestation time to realize their return on investment (Gompers & Lerner, 1999). However, for firms, there is not a clear gestation time preference. While a short time to IPO provides the firm with the capital needed for growth (Yang et al., 2011) it also offers less time to develop the firm and its competitive position. Theoretically, time is an important variable that allows us to test MAT in this context (Hoskisson et al., 2013). Arthurs et al. (2008) applied MAT to underpricing in IPOs and found that careful monitoring and board experience reduced underpricing. The involvement of a serial entrepreneur should make those tasks more manageable. By looking at two outcome variables, one where interests should be aligned, and another where they should not, we can further contribute to MAT theory and aid our understanding of the IPO process.

Theoretical overview: venture capitalists, serial entrepreneurs, and the IPO

MAT examines conflicts of interest among more than one agent group (Arthurs et al., 2008). This theory has been developed to extend traditional agency theory arguments to situations that involve many-to-many relationships instead of the traditional one-to-one relationship. Agency theory is a central and well-established theory that focuses on understanding conflicts of interest between parties, namely principles, and agents. Even though MAT is not widely applied in the field, it is perfect for settings where multiple principals and agents interact. In entrepreneurial settings especially, this theory is very useful, given that in such scenarios, we have multiple principals and agents, each with potentially different objectives and levels of information asymmetry. For instance serial entrepreneurs and VC firms have a vested interest in the success of the startup, but their roles, perspectives and incenteives can be considebly different.

In the beginning, this theory was used to examine the different motives of pension funds and professional investment funds (Hoskisson et al., 2002). Later, Arthurs and colleagues applied it to examine the differences in the motives of executive directors and venture capitalists (Arthurs et al., 2008). In looking at the IPO process MAT considers three main actors—the insiders on the focal firms board, the venture capitalists, and the underwriters. Therefore, we conceptualize the IPO process as a situation of multiple agency with three key parties, the focal firm, the VC firm, which is a principal as well, and the underwriter. Our primary experimental variable is the involvement of a serial entrepreneur as a founder or insider who can use their expertise, social network, or other intangible resources to inhibit potential opportunism by the agents. We generally expect there to be alignment in the interests to maximize the value of the IPO, our first DV, but dissonance in the timing, our second.

Venture capitalists have been shown to provide a certification role, legitimacy, monitoring, and expertise to firms before and after the IPO. They seem to associate with firms with higher uncertainty (Filatotchev et al., 2005). They generally specialize in narrow industries, are involved in longer-term, and provide valuable monitoring services similar to that provided by large stockholders (Jain & Kini, 1995). Barry et al. (1990) showed that VC-backed IPOs were less underpriced—their IPO offer price was closer to their market prices than non-VC-backed IPOs, suggesting that this was due to VC screening and monitoring firms before their IPO. For example, since VCs only fund a small minority of firms, these firms are likely to be the crème de la crème of all firms going public. Also, the authors pointed out that since VCs spend considerable time monitoring firm management pre-IPO, this also increases the quality of the firms brought to IPO. Megginson and Weiss (1991) corroborated that venture-backed IPOs achieved significantly fewer initial returns (i.e., underpriced) with a higher gross spread than non-VC-backed firms. Essentially, having VCs associated with an offering aid in reducing the information asymmetry between the issuing firm, investors, and financial specialists (e.g., underwriters), therefore lowering the total costs of going public and amplifying the net proceeds to the offering firm (Megginson & Weiss, 1991). The authors credited their findings to venture capital “certification.” This certification hypothesis states that firms associated with VCs convey legitimacy and certify the quality of the IPO through their investment in financial and reputational capital (Megginson & Weiss, 1991). This is extremely important given that these IPO firms encounter the liability of newness, which directly enhances the importance of legitimacy for their success (Coombs et al., 2012). Similar to underwriters and their institutional investors, venture capitalists are concerned about their reputation since they are repeat players in this market while the IPO firm will only participate once (Pollock, 2004). Also, VCs seem to be able to attract higher-quality underwriters and auditors. They also suggest that VCs will make sure to price the equity of the firms back closer to the intrinsic value, and then they make sure to pass this information to the IPO market.

Studies have challenged some of these benefits. For instance, Lee and Wahal (2002) found that VC-backed IPOs are more underpriced. Their sample covered IPOs from 1980 to 2000. Another study by Loughran and Ritter (2004) found the average initial returns for VC-backed IPOs during the internet bubble (1999–2000) to be higher than those firms without VC backing. Florin (2005) found no help to post IPO financial performance from having VCs involved and VC involvement was negatively correlated with founder wealth. Another study by Chahine and Wright (2007), also found that the certification role of VC firms as not really effective, where they found that French VC backed firms show greater underpricing when compared with IPOs without VC backing. Explanations for these adverse results, especially for underpricing, are consistent with MAT and center on the relationship between VC firms and underwriters. Venture Capital firms play an iterated game with underwriters, they will see them again for a different venture. Therefore, they may be willing to tolerate modest underpricing in any one deal, in anticipation of future deals. Similarly, any single firm is only one among many in a VC’s portfolio, so they have less incentive to sacrifice relational capital over one firm. Finally, not all VC investments are cashed out at the IPO; therefore, they may be less concerned about underpricing. So while VCs continue to be viewed as a benefit for the entrepreneurial firm, their involvement may not always be uniformly positive.

When it comes to IPO firm valuation, we side with the arguments that show how much more benefits VCs add to IPO firms. These investors are also equity holders and therefore are principals in the focal startup in which they invest, but we should not also forget that they are also agents of the principals who invest in their large venture capital funds. This dual role could create a conflict of interest. In addition to providing expertise to the firm, they often have prior ties with investment banks. Finally, they have a direct ownership stake and interest in having a high IPO valuation. Therefore,

-

H1: The involvement of venture capital firms will be positively correlated with the value of the firm’s IPO.

In addition to value, the IPO serves as the primary way VC firms reap the return on their investment. Many venture capital pools have a limited term, e.g., ten years, and cannot fully recognize the returns on their investments until they are liquidated, usually via an IPO. Therefore, they are pressured to show returns quickly (Sahlman, 1990). They have portfolios of firms, and so there is a potential incentive to move each firm forward quickly at the expense of maximizing the value of any one firm. As a result, they have an incentive to move the firm towards an IPO in as brisk a manner as is practical (Gompers & Lerner, 1999).

This view has held up over time. For instance, Yang et al. (2011) did not find a significant relationship with time to IPO and the authors explained that they were “surprised” to find such a result. They attributed the difference in their results from those of Chang’s (2004) to different samples and time frames, where they just focused on software industry in the growth stage while Chang examined internet based firms in the introductory phase. Chang (2004) found that VC backed firms did go public faster, and suggested that VCs provide legitimacy, which allows the IPO firm the ability to go public faster. We also build on previous work (Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002) by emphasizing that this legitimacy is as important as any other resource that is critical to startups since it leads to access to other vital resources and that IPO firms do acquire more legitimacy by being associated with venture capitalists. A number of other prominent studies also sided with the fact that VCs generally took the IPO as an opportunity to recoup their investments and do so as soon as possible (Arthurs et al., 2008; Gompers & Lerner, 1999). Therefore,

-

H2: The involvement of venture capital firms will be negatively correlated with the time it takes for the firm to go from its founding to its IPO.

Venture capitalists and serial entrepreneurs

While the VC firms are principals with ownership stakes in the IPO firms, a firm is usually only one among many in their portfolio. Furthermore, the IPO firm will have only one IPO, while the VC firm may have multiple interactions with investment banks. Therefore, any one IPO is not as salient to the VC firm as it is to the entrepreneurial firm. This of course is consistent with findings such as VC firms contributing to underpricing (Chahine & Wright, 2007). This suggests that IPO firm and VC firm interests may not be perfectly aligned.

But what if there is an alternate source of expertise available to the founder? As their name implies, serial entrepreneurs are individuals who have founded at least one other business. Experience is often the basis of knowledge and as a result, they possess business experience, personal networks, and possibly personal financial resources that novice founders lack (Politis, 2008). Therefore, the application of their human capital to the firm during the IPO process may serve either to support or as a dissenting view of VC advice that is given to firms. Are firms with serial entrepreneur involvement better able to sidestep potential adverse effects?

In valuing the firm, all three parties—founders, VCs, and underwriters should act in concert. As noted earlier, with a novice founder, the VCs have advice and contacts and can also window-dress an IPO firm to secure higher valuations and reduce information asymmetry between the firm and its underwriter by serving as a credible mediator. Venture capitalists that have a place on the board are agents that will most likely make decisions beneficial to themselves and the venture capital fund. An entrepreneur going through this for the first time is most likely very dependent on VCs and their advice and wisdom. Their help may start long before the IPO when the VC firm is selected. The contracts between VCs and entrepreneurs are stringent, complex, and designed to address several core problems, such as the sorting problem – finding a compatible VC, founder, and firm (Sahlman, 1990). The sorting problem is especially important, Sahlman (1990) discussed how restrictive contractual provisions guarantees that only entrepreneurs who anticipate substantial rewards of VC participation and are certain of their ability to achieve the conditions laid down by the VCs will agree to their participation. Serial entrepreneur involvement can help the firm navigate these challenges and give them insights into the specifics of working with these activist investors. Novice entrepreneurs frequently overestimate their firm’s potential and get involved with VCs in a relationship that might not benefit the founder or the firm. The serial entrepreneur can help the firm navigate this complex relationship.

Serial entrepreneurs are knowledgeable about the IPO process and can provide an alternative to the guidance offered by the VCs to the IPO firm. While some studies found no effect (c.f. Alsos & Kolvereid, 1999), recent evidence suggests a positive effect for serial entrepreneurs on firm performance though it exhibits regression to the mean (Parker, 2013). Serial entrepreneurs also realize that VCs are helpful but must be managed since they have objectives that might not precisely match the founder’s objectives. They can use their networks to aid in securing better contract terms with the VCs and ensure they present their firm accurately and its future potential. Serial entrepreneurs may also be more intrinsically motivated—they like the excitement and the rush of starting a business and seeing it through to an IPO. Many founders/ entrepreneurs/ business owners eventually become more of a manager, and they never return and start new businesses again, so there is something different about serial entrepreneurs. Like novice entrepreneurs, serial entrepreneurs will make decisions that are best for themselves in light their agency relationship with all of their different investors and board members, but have greater ability due to their social and knowledge capital.

So, given their experience and expertise, and the fact that their interests here align, we would expect serial entrepreneurs to facilitate the role of venture capitalists in maximizing the size of the IPO. Therefore,

-

H3: Serial entrepreneur involvement will positively moderate venture capitalist involvement to increase the value of the IPO.

However, when it comes to timing, the interests of serial entrepreneurs and VC firms may not be in alignment. As discussed earlier, due to their term structure, portfolio of firms, and need to show returns to their investors, VC firms have a clear motivation to have the IPO as quickly as possible. However, this is not necessarily the case for the IPO firm. The firm wants a successful IPO but has a broader range of interests than the VC firm. While having the financial resources from the IPO earlier is preferable to later, the firm may want to see its strategy and competitive position become more established before the IPO. After all, the firm will only get one shot at its IPO. Therefore, when looking for a potential alternative voice on the board, the serial entrepreneur is in a position to act as a counterbalance to the agenda of most VC firms. This is especially important since serial entrepreneurs are usually more focused on the technical issues of the venture (Westhead et al., 2005). Therefore, they are liable to be cognizant of remaining challenges and issues to be solved before the firm is ready for its IPO. They may provide a firm’s founder, or its governing body with an authoritative differing view delaying the launch of the IPO.

-

H4: Serial entrepreneur involvement will moderate venture capitalist involvement to lengthen the time to the firm’s IPO.

Method

Sample

We developed a sample of all U.S. high-tech firms undertaking an IPO between 2002 and 2006. The data were hand collected from IPO firm prospectuses found on the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC’s) Electronic Data Gathering and Retrieval (EDGAR) system for IPOs. Based on Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes, firms were identified as operating in high-technology industries sectors (Daily et al., 2005). The time frame of this study was selected to omit extremely low or high-volume years (e.g., DotCom bubble of 1999 and 2000). Consistent with prior research, holding companies, financial institutions, and real estate investment trusts (REITs) were excluded from the sample (e.g., Fischer & Pollock, 2004). Three firms were also dropped since no prospectus was found for them. The final sample consisted of 211 firms.

Measures

Dependent variable

Two different measures of success were used: IPO Value and time-to-IPO. IPO Value represents the capital raised at IPO. It is the total value of the capital raised minus the underwriters’ fees as presented on the cover page of the firm’s prospectus (Deeds et al., 1997; Gulati & Higgins, 2003; Mousa & Reed, 2013; Zimmerman, 2008). IPO value is both an IPO measure of firm performance (Gulati & Higgins, 2003; Zimmerman, 2008), and a measure of how the market values a company at the time of the initial offering (Deeds et al., 2004).

Time-to-IPO was measured as the number of years from incorporation date to the IPO date (i.e., firm age at IPO) (Chang, 2004; Shepherd & Zacharakis, 2001; Fischer & Pollock, 2004; Yang et al., 2011). Scholars in the IPO literature have viewed time to IPO as a good performance measure during a stage in the firm’s life cycle when other measures are simply not available (Chang, 2004).

Independent variables

This study utilized two independent variables, Serial Founders and Venture Capital Backing (VC-backing). Serial Founders variable was operationalized by using a dichotomous variable (1,0) to capture whether the top management team of the IPO firm had at least one member on it that had founded at least one other company. Venture Capital Backing, the second independent variable, was calculated by combining the rounds of financing as recorded in the final prospectus (Gulati & Higgins, 2003; Mousa & Reed, 2013). This variable has been shown to influence the ability of an IPO firm to raise capital (Gulati & Higgins, 2003; Megginson & Weiss, 1991; Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002), increase chances of survival (Khurshed, 1999), and influence the amount of slack resources a firm has (MacMillan et al., 1989).

Control variables

Per the precedent established in other IPO studies, we controlled for Firm Size since research shows that larger IPO firms tend to outperform smaller ones in terms of stock appreciation (e.g., Megginson & Weiss, 1991). We used log total firm employees to account for skewness in the data. Organizational Slack represents cash reserves minus average industry cash reserves (Mousa & Reed, 2013). We included Firm Risk and we calculated it by adding the total number of risk factors that were mentioned in the prospectus (Welbourne & Andrews, 1996). We controlled for Industry Effect by including a dummy variable for industry using the 2-digit SIC codes, with SIC code 73 (software) being the omitted category. We also controlled for firm innovation given its impact on IPO firm performance (Heeley et al., 2007), and measured it using R&D intensity and Patent intensity. Both R&D and Patent Intensity were operationalized by dividing R&D spending and firm Patents respectively by the number of firm employees. We also controlled for Governance Strength, which was calculated to account for the variance attributed to insider ratio as the number of officer directors divided by the total number of board members (Harris & Shimizu, 2004).

Methods of analysis

Consistent with other IPO research, all hypotheses in regards to the IPO firm-valuation were analyzed using partial hierarchical multiple regression analysis (Dimov & Shepherd, 2005; Zimmerman, 2008). This type of analysis allows the researcher to determine the order of entry of the variables.Footnote 1 We used a three-step hierarchical regression analysis. The first model contained all of the control variables. In the second model the independent variables were added to the base model. The interaction term was added only in the third model.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for all variables. Overall, the correlations are low to intermediate. The highest variance inflation factors (VIF) for all terms in both models was less than 2.2, well below the VIF of 10 that is indicative of ‘harmful collinearity’ (Kennedy, 1992:183).Footnote 2 The average of value of the IPO in our sample was $92.7 million while the average age was 10.7 years. This sample had on average 691 employees, $54 million invested in all rounds of VC funding up to IPO, 80% of these IPO firms had at least one serial founder involved at the helm of the company, invested $249 million in R&D and held 37 patents.

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of our regression analysis predicting IPO Valuation and Time-to-IPO using our venture capital backing, serial entrepreneurial logic, and control variables. Three different models were specified in each table. Model 1 tested only the effects of control variables on both of our dependent variables (Valuation and Time-to-IPO). Model 2 tested for the main effects of the venture capital backing and serial entrepreneurial logics (Hypothesis 1 and 2). Model 3 tested interaction effects of the VC-backing logic with the serial entrepreneurial logic (Hypothesis 3 and 4) (Please see Table 4).

Hypothesis 1 predicted that venture capital backing would be positively associated with IPO valuation while the second hypothesis said VC backing would be negatively associated with Time-to-IPO. The results provided show support for these hypotheses. Therefore VC-backed firms do have a positive and significant impact on IPO Value and they do have a negative, i.e. faster, and significant impact on the time needed for IPO firms to go public. This is consistent with other published studies using US data that has found VC backed IPOs generally do outperform non-VC backed issues in terms of financial, operational, and long-term performance (e.g., Jain & Kini, 1995, 2000; Megginson & Weiss, 1991). Our results add to this literature by examining a different dependent variable (IPO valuation). Further, based on the theory developed in support of Hypothesis 2, the involvement of venture capital firms does lead to shorter time to IPO. Such results seem consistent with the idea that VCs can contribute meaningfully to firms but with the proviso that they have time constraints they must meet.

Hypothesis 3 and 4 suggest that the interaction term serial entrepreneurs will moderate both relationships presented in Hypothesis 1 and 2. Hypothesis 3 does not confirm our hypothesis that serial entrepreneur involvement with VC firms will result in a greater valuation for the firm. On the contrary, it seems to do exactly the opposite of what we expected. The interaction term thus is significant (B = -0.526; p < 0.01) showing the interaction of serial founders with VC backing actually impacts valuation in a negative and significant manner.

This is a puzzling result. Interestingly, empirical work has shown that there are low rates of VC firms working again with the same serial entrepreneurs (Wright et al., 1997). It may be possible that interacting with VC firms is not a pleasant experience, for example, VC firms are willing to change leadership at any time. We know at least one major VC firm replaces about half of the entrepreneurs that it funds (e.g., Rocco Forums on the Future, Video at James Madison University, Virginia, 2023). Where a novice entrepreneur may not be willing to “push back” against the advice of VC firms, serial entrepreneurs may be more inclined to do so. If so, the greater social and knowledge capital possess by a serial entrepreneur may result in excess conflict to such an extent that it lowers the value of the IPO.

Consistent with multiple agency theory and in support of hypothesis 4, the interaction term is positive and significant (B = 0.701; p < 0.01), and thus it shows serial entrepreneur involvement slows progress towards the IPO. We suspect that the involvement of a serial entrepreneur makes it easy for any stakeholder to access a competing knowledge base to push back against pressure to speed up the IPO process and facilitates stronger monitoring.

Additional analyses were conducted to assess whether the results reflect robust relationships in the data. The regression equations used to test all hypotheses were rerun with 25 and 50 percent of the sample randomly deleted. No results changed in the first robustness check but with the second robustness check the only change was support for hypotheses 4, which dropped in significance from p < 0.05 to p < 0.10. Overall, these findings suggest that the results of this study are not spurious but rather do reflect a definite structure within the data that is supportive of the hypotheses.

Discussion and conclusion

Since the early work of MacMillan et al. (1989) the role of serial entrepreneurs has been explored. In looking at their interaction with venture capital firms, at least for those firms that make it to the IPO, this paper found that serial entrepreneurs hindered the efforts of venture capitalists to increase the value of the firm’s IPO and move quickly to an IPO. While a lot of work has been focused on serial entrepreneurs and the initiation of the venture, clearly serial entrepreneurs play an important role in the IPO process.

Theoretically, this paper illustrates the value of adopting a MAT lens to managerial studies. By looking at many to many relationships MAT enables richer conceptualizations of the IPO process. Agency theory normally focuses on one-to-one relationships, and this is clearly not the case in an IPO context. For example, VCs have obligations to their own investors, the IPO firm, and ongoing relationships with underwriters. Even when their interests appeared aligned, serial entrepreneurs did not work in concert with VCs for IPO valuation. This shows MAT’s potential value for future research. Indeed, while they were focused on boards Filatotchev et al. (2005), found complex agency relationships between founders, including serial founders, and VCs. Introducing another actor that can moderate the information asymmetry between firms and VCs, in our case the serial entrepreneur, impedes each from achieving their objectives, even if their interests are aligned.

This paper also expanded the range of entrepreneurial effectiveness by looking at the time to IPO variable. Time to IPO is a potential agency issue that can drive a wedge between parties. Time to IPO is an important strategic consideration because it accentuates the tension between the venture capitalist's ongoing commitment of talent and their opportunity costs against the need for the IPO firm to develop a solid strategic foundation fully.

Part of the unexpected results centered on the value of the IPO may be driven by the fact that it has two components, the valuation of the firm and the percentage of the firm that is offered in the IPO. While VC firms and serial entrepreneurs should be in full accord regarding seeing a higher valuation, they may be in confict regarding the percentage of the firm to offer in the IPO. This could explain our unexpected results.

Limitations

One of our study’s limitations is that it only focuses on US IPOs; comparing these results with other countries, especially emerging economic powers such as China and South Korea would be interesting. Considerable differences might even be found in Western countries, for example, according to the European Venture Capital Association (EVCA) statistics, the French VC industry is one of the most dynamic in Europe and thus might be perfect for such a study. We did not control for the number of prior ventures of the serial entreprenuers nor the prestigue of the venture capital firms. Another area is serial entrepreneurs as the founders/CEOs of the IPO firms, where we would expect a dramatically reduced role for venture capitalists. Another opportunity would be to consider if these results would hold even in entirely different contexts under certain circumstances, for instance, the accession of several former communist countries (e.g., Hungry) to the European Union in 2004, thus leading to substantial migration to Western Europe (Felker, 2011; Gittins et al., 2015).

Future directions

In looking at future studies on serial entrepreneurs, one of the biggest unanswered questions is the regression to the mean effect demonstrated by serial entrepreneurs (Parker, 2013). Why don’t they do so much better than entrepreneurial novices? Parker (2013) partially attributes this to human capital depreciation. Our work here suggests a driver of this depreciation. Serial entrepreneurs take positive and negative experiences away from their earlier ventures, including interactions with VC firms. Especially in a high-stakes IPO context, negative prior experiences will be amplified – our reverses sting far more than our successes. Thus, this history of conflict shows up as the regression to the mean effect.

The opportunities suggested by our findings here are considerable. Do VCs actually give sub-optimal advice to firms, at least regarding the timing of their IPO? Why are serial entrepreneurs able to resist their interests in moving to an IPO? Is it because serial entrepreneurs already have considerable personal financial resources? Does it have to do anything with their belief systems, cognitive maps, or mental models about entrepreneurship (Laukkanen, 2023)?

In addition, although beyond the scope of this study, we hope that researchers might benefit from collecting and observing change over time in issues related to serial founders, venture capitalists, and IPOs. Such longitudinal data would provide the researchers an opportunity to explore the temporal state of IPO Valuation and Time to IPO and their antecedents at a specific point in time but also it will allow the researcher to analyze the evolutionary trajectory of the IPO firm.

Future research could also investigate whether such findings will hold in international settings and dig deeper into the interplay between different types of venture capitalists and serial founders. For example, Tykvová (2006) found that in Germany, in the period before the IPO, independent and corporate VC firms financed their portfolio firms longer when compared to bank-dependent and public VC firms.

We also hope that researchers will consider delving even more profoundly by exploring the role of different serial entrepreneurs. Previous research has found that not all serial entrepreneurs are homogenous, and they don’t all necessarily behave in the same way, and thus further disentangling the components of entrepreneurial human capital, how it evolves, and how it is used should be a fruitful area of research as well (Ucbasaran et al., 2003). Focusing on serial entrepreneurs in social entrepreneurship, an innovative field that is getting more and more attention every day (Kraus et al., 2014), might add tremendous knowledge to what we know today about serial entrepreneurs. Also, delving deeper into the important question of entrepreneurial metacognition of serial entrepreneurs and how it is different from that of nascent entrepreneurs or even venture capitalists seems to be helpful here. A recent study by Bastian and Zucchella (2022) built on previous literature and found, for instance, that nascent entrepreneurs rely heavily on input from outsiders when they are building a business and that they go through an important reflective and learning process that helps with engagement with local ecosystems, all important to the success of young firms.

For entrepreneurs, serial or otherwise, the IPO remains an important landmark. Even if the firm is acquired privately, the valuation process is similar to an IPO’s. Involving a serial entrepreneur can help achieve higher valuation for the firm, albeit at the cost of possibly taking longer to realize that return, at least in the presence of venture capitalist firms.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this study can be made available upon a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Notes

This is not to be confused with Hierarchical Linear Models that deals with observations that are not independent.

The VIF is computed as 1/(1 – r.2).

References

Alsos, G. A., & Kolvereid, L. (1999). The business gestation process of novice, serial, and parallel business founders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(4), 101–114.

Arthurs, J. D., Hoskisson, R. E., Busenitz, L. W., & Johnson, R. A. (2008). Managerial agents watching other agents: Multiple agency conflicts regarding underpricing in IPO firms. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2), 277–294.

Barry, C., Muscarella, C., Peavy, J., III., & Vetsuypens, M. (1990). The role of venture capital in the creation of public companies: Evidence from the going public process. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 447–471.

Bastian, B., & Zucchella, A. (2022). Entreprenail metacognition: A study on nascent entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 18, 1775–1805.

Birley, S., & Westhead, P. (1994). A comparison of new businesses established by “novice” and “habitual” founders in Great Britain. International Small Business Journal, 12(1), 38–60.

Bygrave, W. D., & Stein, M. (1990). The anatomy of high-tech IPOs: Do their venture capitalists, underwriters, accountants, and lawyers make a difference? In N.C. Churchill et al. (Eds.), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Babson College.

Chang, S. (2004). Venture capital financing, strategic alliances, and the initial public offerings of internet startups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(5), 721–741.

Chahine, S., & Wright, M. (2007). Venture capitalists, business angels, and performance of entrepreneurial IPOs in the UK and France. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 34, 505–528.

Coombs, J. E., Bierly, P. E., & Gallagher, S. (2012). The impact of different forms of IPO firm legitimacy on the choice of alliance governance structure. Journal of Management and Organization, 18(4), 516–536.

Daily, C. M., Certo, S. T., & Dalton, D. R. (2005). Investment bankers and IPO pricing: Does prospectus information matter? Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 93–111.

Deeds, D. L., Decarolis, D., & Coombs, J. E. (1997). The impact of firm-specific capabilities on the amount of capital raised in an initial public offering: Evidence from the biotechnology industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1), 31.

Deeds, D. L., Mang, P. Y., & Frandsen, M. L. (2004). The influence of firms’ and industries’ legitimacy on the flow of capital into high-technology ventures. Strategic Organization, 2(1), 9–34.

Dimov, D. P., & Shepherd, D. A. (2005). Human capital theory and venture capital firms: Exploring ‘home runs’ and ‘strike outs.’ Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 1–21.

Felker, J. A. (2011). Professional development through self-directed expatriation: Intentions and outcomes for young, educated Eastern Europeans. International Journal of Training and Development, 5(1), 76–86.

Filatotchev, I., Chahine, S., Wright, M., & Arberk, M. (2005). Founder’s characteristics, venture capital syndication and Governance in Entrepreneural IPOs. Int Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1, 419–439.

Fischer, H., & Pollock, T. (2004). Effects of social capital and power on surviving transformational change: The case of initial public offerings. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 463–481.

Florin, J. (2005). Is venture capital worth it? Effects on firm performance and founder returns. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 113–136.

Gartner, W. B., Starr, J. A., & Bhat, S. (1998). Predicting new venture survival: an analysis of anatomy of a start-up. Cases from Inc. Magazine. Journal of Business Venturing, 14, 215–232.

Gittins, T., Lang, R., & Sass, M. (2015). The effect of return migration driven social capital on SME internationalisation: a comparative case study of IT sector entrepreneurs in Central and Eastern Europe. Review of managerial Science, 9, 385–409.

Gompers, P. A., & Lerner, J. (1999). The venture capital cycle. MIT Press.

Gulati, R., & Higgins, M. C. (2003). Which ties matter when? The contingent effects of interorganizational partnerships on IPO success. Strategic Management Journal, 24(2), 127.

Harris, I. C., & Shimizu, K. (2004). Too busy to serve? An examination of the influence of overboarded directors. Journal of Management Studies, 41, 775–798.

Heeley, M. B., Matusik, S. F., & Jain, N. (2007). Innovation, appropriability, and the underpricing of initial public offerings. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 209–225.

Hoskisson, R. E., Hitt, M. A., Johnson, R. A., & Grossman, W. (2002). Conflicting voices: The effects of institutional ownership heterogeneity and internal Governance on corporate innovation strategies. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 697–716.

Hoskisson, R. E., Arthurs, J. D., White, R. E., & Wyatt, C. (2013). Multiple agency theory: An emerging perspective of corporate governance (pp. 673–702). Oxford Handbook of Corporate Governance.

Jain, B. A., & Kini, O. (1995). Venture capitalist participation and the post-issue operating performance of IPO firms. Managerial and Decision Economics, 16, 593–606.

Jain, B. A., & Kini, O. (2000). Does the presence of venture capitalists improve the survival profile of IPO firms? Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 27, 1139–1176.

Kennedy, P. (1992). A Guide to Econometrics. MIT Press.

Khurshed, A. (1999). Initial Public Offerings. An Analysis of the Post-IPO Performance of UK Firms. Unpublished PhD thesis (University of Reading).

Kraus, S., Filser, M., O’Dwyer, M., & Shaw, E. (2014). Social Entrepreneurship: An exploratory citation analysis. Review of Managerial Science, 8, 275–292.

Kutsuna, K., Cowling, M., & Westhead, P. (2000). The short-run performance JASDAQ companies and venture capital involvement before and after flotation. Venture Capital, 2(1), 1–25.

Lange, J. E., Bygrave, W., Nishimoto, S., Roedel, J., & Stock, W. (2001). Smart money? The impact of having top venture capital investors and underwriters backing a venture. Venture Capital, 3(4), 309–326.

Lee, P., & Wahal, S. (2002). Grandstanding, certification and the underpricing of venture capital backed IPOs. Journal of Financial Economics, 73(2), 375–407.

Lin, S., Yamakawa, Y., & Lin, J. (2019). Emergent learning and change in strategy: empirical study of Chinese serial entrepreneurs with failure experience. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15, 773–792.

Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. (2004). Why has IPO underpricing changed over time? Financial Management, 33(3), 5–37.

Laukkanen, M. (2023). Understanding the contents and development of nascent entrepreneurs’ belief systems. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19, 1289–1312.

MacMillan, I. C., Kulow, D. M., & Khoylian, R. (1989). Venture capitalists’ involvement in their investments: Extent and performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(1), 27.

Megginson, W. L., & Weiss, K. A. (1991). Venture capitalist certification in initial public offerings. Journal of Finance, 46(3), 879–903.

Mousa, F. T., & Reed, R. (2013). The impact of slack resources on high-tech IPOs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(5), 1123–1147.

Mousa, F. T., & Wales, W. (2012). Founder effectiveness in leveraging entrepreneurial orientation. Management Decision, 50(2), 305–324.

Parker, S. C. (2013). Do serial entrepreneurs run successively better-performing businesses? Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 652–666.

Politis, D. (2008). Does prior start-up experience matter for entrepreneurs’ learning? A comparison between novice and habitual entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(3), 472–489.

Pollock, T. G. (2004). The benefits and costs of underwriters’ social capital in the US initial public offerings market. Strategic Organization, 2(4), 357–388.

Sahlman, W. A. (1990). The structure and governance of venture-capital organizations. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 473–521.

Semrau, T., & Werner, A. (2014). How exactly do network relationships pay off? The effects of network size and relationship quality on access to start-up resources. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 501–525.

Shepherd, D. A., & Zacharakis, A. (2001). Speed to initial public offering of VC-backed companies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(3), 59–70.

Tykvová, T. (2006). How do investment patterns of independent and captive private equity funds differ? Evidence from Germany. Financial Markets and Portfolio Management, 20, 399–418.

Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Westhead, P. (2003). A longitudinal study of habitual entrepreneurs: Starters and acquirers. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 15(3), 207–228.

Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (1998). Novice, portfolio, and serial founders: are they different? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 173–204.

Westhead, P., Ucbasaran, D., & Wright, M. (2005). Decisions, actions, and performance: Do novice, serial, and portfolio entrepreneurs differ? Journal of Small Business Management, 43(4), 393–417.

Welbourne, T. M., & Andrews, A. O. (1996). Predicting the performance of initial public offerings: Should human resource management be in the equation. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 891–919.

Wright, W., Robbie, K., & Ennew, C. (1997). Venture capitalists and serial entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 227–249.

Yang, Q., Zimmerman, M., & Jiang, C. (2011). An empirical study of the impact of CEO Characteristics on new firms’ time to IPO. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(2), 163–184.

Zang, J. (2011). The advantage of experienced start-up founders in venture capital acquisition: Evidence from serial entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 36, 187–208.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2008). The influence of top management team heterogeneity on the capital raised through an initial public offering. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 391.

Zimmerman, M. A., & Zeitz, G. J. (2002). Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. The Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 414–431.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mousa, FT., Gallagher, S.R. Managing conflicting agendas: serial entrepreneurs and venture capitalists in the IPO process. Int Entrep Manag J 20, 1197–1214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00950-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00950-0