Abstract

Business plan competitions (BPCs) are opportunities for nascent entrepreneurs to showcase their business ideas and obtain resources to fund their entrepreneurial future. They are also an important tool for policymakers and higher education institutions to stimulate entrepreneurial activity and support new entrepreneurial ventures from conceptual and financial standpoints. Academic research has kept pace with the rising interest in BPCs over the past decades, especially regarding their implications for entrepreneurial education. Literature on BPCs has grown slowly but steadily over the years, offering important insights that entrepreneurship scholars must collectively evaluate to inform theory and practice. Yet, no attempt has been made to perform a systematic review and synthesis of BPC literature. Therefore, to highlight emerging trends and draw pathways to future research, the authors adopted a systematic approach to synthesize the literature on BPCs. The authors performed a systematic literature review on 58 articles on BPCs. Several themes emerge from the BPC literature, including BPCs investigated as prime opportunities to develop entrepreneurial education, the effects of BPC participation on future entrepreneurial activity, and several attempts to frame an ideal BPC blueprint for future contests. However, several research gaps emerge, especially regarding the lack of theoretical underpinnings in the literature stream and the predominance of exploratory research. This paper provides guidance for practice by presenting a roadmap for future research on BPCs drawing from the sample reviewed. From a theoretical perspective, the study offers several prompts for further research on the topic through a concept map and a structured research agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Business plan competitions (BPCs) give nascent entrepreneurs the chance to present their business ideas to an industry and investment peer group tasked with judging each project and picking the most viable one (Overall et al., 2018). Winners are awarded various prizes (McGowan & Cooper, 2008). The purpose of BPCs is to stimulate new entrepreneurial activity and support novel entrepreneurial ideas (Kwong et al., 2012). In return, BPC organizers emphasize the benefits of participating, such as cash prizes and financing (McGowan & Cooper, 2008), visibility and reputational benefits (Parente et al., 2015), networking with other aspiring entrepreneurs (Thomas et al., 2014), and meeting potential stakeholders, including customers and investors (Passaro et al., 2020).

BPCs have been used by new entrepreneurs to kickstart their business ideas (Cant, 2018). They have been popular throughout the years, especially during the global recession in the first decade of the 2000s. BPCs have become widely popular across both developed (Licha & Brem, 2018) and developing countries (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018; McKenzie & Sansone, 2019), as poor economic conditions have driven young entrepreneurs toward any opportunity they can find (Cant, 2018). Since the origin of BPCs in the USA in the 1980s (Buono, 2000), several universities have implemented them in their educational ecosystem to foster practical learning. From there, BPCs have rapidly spread in Europe (Riviezzo et al., 2012) and within developing nations in Asia (Wong, 2011) and Africa (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011). Despite contextual peculiarities, the significance of BPCs is equally pertinent for developed and emerging economies (Tipu, 2018), as they contribute to shaping a lively local entrepreneurial fabric (Barbini et al., 2021).

Opportunities arising from BPC participation come in various forms, including knowledge (Barbini et al., 2021), networking, and promotion (Cant, 2016a); however, finding economic resources to finance entrepreneurial ventures has proven to be the main concern (Kwong et al., 2012; McGowan & Cooper, 2008). BPCs are attractive to entrepreneurs, as they can be prime opportunities not only to receive feedback on their ideas, but also to get the monetary funds needed to realize them (Mosey et al., 2012). In addition, a successful BPC does not merely identify the most intriguing business idea but also supports entrepreneurs during the early stages of their new ventures, whether or not they win the competition (Watson et al., 2015).

Several research streams have emerged around the topic of BPCs (Cant, 2018). For example, entrepreneurial education has been investigated in several studies (Licha & Brem, 2018; Olokundun et al., 2017) as a way to effectively provide learning support to nascent entrepreneurs and boost their chances of success. Moreover, university-based BPCs are being explored in terms of their potential as learning experiences and how specific lessons learned during these competitions may affect future entrepreneurial orientations (Overall et al., 2018). For example, some argue that promoting sustainable production during BPCs has a tangible impact on the integration of sustainability practices into future business activities (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020).

Start-up competitions have gained global prominence since the 1980s (Kraus & Schwarz, 2007; Ross & Byrd, 2011). Today, they are a popular form of support for nascent entrepreneurs (Dee et al., 2015), featuring steady growth in numbers over recent years (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020). Consistent with BPCs’ importance, the literature examining them is growing, with an increasing number of empirical studies published each year. However, despite the attention from policymakers and academics, no attempts have been made thus far to review the literature on BPCs systematically. Additionally, there is a need for a structured research agenda that could shed light on currently unexplored topics in entrepreneurship research, such as the role of institutions in emergent entrepreneurial intentions (Audretsch et al., 2022; Barbini et al., 2021), contextual factors stimulating nascent entrepreneurial intentions (Zhu et al., 2022), and the development of richer theory about practical entrepreneurial training (Clingingsmith et al., 2022).

To the best of our knowledge, the only previous attempt at synthesizing BPC literature was performed by Tipu (2018). While their contribution is of absolute importance, its scope was limited to 22 papers published in the early 2000s and late 90 s, thus leaving a consistent portion of recent academic literature unexplored. Consequently, we believe that a systematic review of the BPC literature could be of interest to both practitioners and academics. Building on previous systematic literature reviews (SLRs) from the entrepreneurship field, we aim to provide a detailed analysis of the relevant literature on BPCs. We focus on several key aspects of BPCs that emerged from the analysis, starting with the ways in which they are currently implemented, the benefits they provide to new entrepreneurs, and the role played by BPC promotion in the early stages of the entrepreneurial life cycle (Cant, 2016a). Our analysis reveals several factors that influence the successful implementation of BPCs as ways to boost the effectiveness of novel entrepreneurial ventures, including entrepreneurial education for individuals who take part in the program (McGowan & Cooper, 2008) and entrepreneurs’ personal traits and dispositions (Kwong et al., 2012). Therefore, our study is not limited to a synthesis of the existing literature on the topic; rather, it develops a comprehensive framework for both professionals and academic researchers to guide future projects on BPCs. This study is guided by four main research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: What is the current research profile of BPC literature?

-

RQ2: What are the key emerging topics to be found in BPC literature?

-

RQ3: What research gaps are currently present in the BPC literature and what future research agenda can be set according to said gaps?

-

RQ4: Can a comprehensive conceptual framework be synthesized from the literature to help academics, practitioners, and other relevant stakeholders?

Drawing on previous SLR research on entrepreneurship (Kraus et al., 2020), we synthesized the literature to reach our research goal and answer the questions listed above. RQ1 was addressed by gathering all the available literature that satisfied the inclusion criteria in terms of research scope, relevance, and keywords. The research profile was then obtained by conducting several descriptive observations meant to understand the volume of annual scientific production, the most cited sources, the geographical focus, the theoretical frameworks used by the authors, and the emerging themes across the sample. RQ2 was addressed by reviewing the literature presented in the sample through in-depth content analysis techniques. From the analysis, the following themes emerged across the sample: (1) BPCs as opportunities for entrepreneurial education, (2) the role of BPCs in the promotion and visibility of nascent entrepreneurs, (3) the contexts surrounding BPCs, and (4) methodological choices and research design in BPC publications. Regarding RQ3, we manually reviewed each document to identify relevant research gaps in the BPC literature. This allowed us to suggest several research questions that could serve as a foundation for future studies. Finally, RQ4 was addressed by developing a framework that synthesized the thematic findings of our SLR.

The present SLR can contribute significantly to both theory and practice. Overall, SLRs critically assess and synthesize extant research, developing a comprehensive theoretical framework that can guide scholars and practitioners. In other words, a systematic review highlights the different thematic areas of prior research, delineates the research profile of the existing literature, identifies research gaps, projects possible avenues for future research, and develops a synthesized research framework on the topic (Dhir et al., 2020). Thus, from a theoretical perspective, our study should interest a broad range of researchers, as it links back to the ongoing global conversation regarding BPCs. It does so by synthesizing the knowledge on the topic and formulating a structured research agenda that could serve as a reference for researchers to conduct future studies and address issues of topical interest that have yet to receive sufficient attention from authors. The research agenda is built upon extant gaps found in our in-depth analysis of the sample. Similarly, practitioners can use the findings to recognize the drivers and outcomes of BPC programs and shed light on their core characteristics when designing one. Likewise, policymakers should use the present work as a blueprint for BPC planning, as the findings presented in this paper summarize how to set up a BPC effectively.

The article begins by outlining the scope of the research and explaining what types of studies will be included in the SLR in terms of content. We then explain the methodology used to gather the research sample and provide a descriptive overview of the data. Next, we provide a thematic review of the studies featured in the SLR. We identify gaps in the literature and avenues for further research before finally discussing the study’s limitations, as well as its theoretical and practical implications.

Scope of the review

Specifying the scope of the SLR and outlining its conceptual boundaries enhance the search protocol's transparency and academic rigor (Dhir et al., 2020). We achieved the above by clearly defining the theoretical background of the phenomenon under investigation, thus establishing the definition of the term BPC and employing it as the conceptual boundary of the review.

The BPC literature is part of a broader stream of competition-based learning in higher education institutions (Connell, 2013; Olssen & Peters, 2005). The peculiarities of BPCs consist in the presence of rewards for participation (Brentnall et al., 2018), the development of core entrepreneurial competencies (Arranz et al., 2017; Florin et al., 2007), and the overall effectiveness in terms of entrepreneurial survival (Jones & Jones, 2011; Russell et al., 2008). Previous research has focused on the core elements of BPC programs, such as mentoring, feedback, and networking; the way they affect future entrepreneurial lives (McGowan & Cooper, 2008; Watson et al., 2015; Watson & McGowan, 2019); and the rewards from BPC participation (Russell et al., 2008).

From a geographical perspective, the significance of BPCs is equally pertinent for developed and emerging economies (Tipu, 2018), albeit nascent entrepreneurs face unique challenges in developing countries, such as the lack of educational support (Hyder & Lussier, 2016) and institutional instability (Farashahi & Hafsi, 2009). We find the most significant levels of literary production in the USA (Buono, 2000), where BPCs originated back in the 1980s, and Europe (Riviezzo et al., 2012). BPC programs are also gaining traction in developing countries, especially in Asia (Wong, 2011) and Africa (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011). In China, for instance, BPCs are recognized as a reasonable means to obtain practical entrepreneurial knowledge (Fayolle, 2013). Similarly, in Kenya, there is an unprecedented level of interest in BPCs, especially from stakeholders involved in entrepreneurial education (Mboha, 2018). Finally, in Australia, Lu et al. (2018) noted the importance of funding from the federal government, such as the New Colombo Plan or the Endeavour Mobility funding schemes, in terms of support and promotion of BPC programs.

Despite the broad geographical scope of BPC literature, there is still a considerable paucity of research on the impact of BPCs on local entrepreneurship and enterprise development. Additionally, the few published studies feature mixed results. For instance, the study by Russell et al. (2008) reported a positive impact of the MI50K Entrepreneurship Competition in terms of job creation and overall funding obtained. However, the results of the study by Fayolle and Klandt (2006) are contradictory, as they note how entrepreneurial training via BPC participation does not always equate to a successful future venture. In this regard, BPC literature echoes decades-old controversial stances in entrepreneurship research, such as the perceived usefulness of business plans (Gumpert, 2003; Leadbeater & Oakley, 2001).

At this juncture, we also consider it prudent to formulate the definition of BPC that will be used as a conceptual boundary for the present study. While BPCs worldwide share a core definition and essence, they come in various forms (McKenzie, 2017). We adopted Passaro et al.'s (2017) definition of BPC, highlighting three essential structural and procedural features. The first is the presence of an organizing committee overseeing the competition and sponsors willing to invest in the most promising entries (Bell, 2010). Second, the participants are required to submit business plans to participate in the competition, and participants often consist of teams, as knowledge sharing across multiple people is deemed a crucial component of entrepreneurial success (Weisz et al., 2010). Third, after an initial screening, only participants with the most promising ideas are asked to further develop their business plans in the final stages of the competition (Burton, 2020). Thus, with the above conceptual scope in mind, our study includes contributions that have examined BPCs, their core characteristics, their implications for entrepreneurship education, and both the antecedents and consequences of BPC participation. However, we do not include studies investigating entrepreneurship education, universities' incubators, and generic entrepreneurial themes. Such studies have already been discussed at length by previous researchers.

Methods

The SLR approach was undertaken in an attempt to present the current literature in a comprehensive and extensive way. SLRs have been widely used in entrepreneurship research, and we use previously published SLRs as a methodological reference to guide our study (Mary George et al., 2016; Paek & Lee, 2018; Tabares et al., 2021). In accordance with previous work (Hu & Hughes, 2020), we performed a systematic review of BPC literature divided into two distinct steps. We first extracted the dataset required to perform the study, in what we will refer to as the data extraction phase. We later profiled the sample obtained in terms of descriptive statistics, such as annual scientific production, most cited countries, authors’ networks, and collaborations. Additional analyses were conducted by using the VOSviewer software tool (version 1.6.10., Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands) and Microsoft Excel (Dhir et al., 2020). The tools make use of bibliographic data to determine the frequencies of the published materials, design relevant charts and graphs, construct and visualize the bibliometric networks, and calculate the citation metrics.

Data extraction

The three central databases utilized for the present study are Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and Google Scholar, as per the suggestions by Mariani et al. (2018). The first step in order to conduct the extraction of data was to identify the appropriate set of keywords. Based on the conceptual boundaries of the SLR, we determined an initial set of keywords. The keywords included ‘business plan competitions', ‘business plan contests’, and ‘business creation competitions’. The above keywords were used to perform an initial search on Google Scholar to examine if our keywords were sufficient. The first 50 results were taken into consideration (Dhir et al., 2020). We also searched the exact keywords in top journals, such as Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice; Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal; International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal; and Entrepreneurship Research Journal. Subsequently, we updated the list with keywords from the above sources. We consulted the panel to finalize the set of keywords, which ultimately resulted in the following: business plan competition*, business creation competition*, social business plan competition*, business plan contest*, business creation competition*, pitch competition*, pitch contest*. Data were collected from two databases, Scopus and WoS, which are generally well renowned in previous SLR studies on entrepreneurship (Hu & Hughes, 2020). Then, a rigorous set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was established. As for the inclusion criterion, we wanted to include only peer-reviewed works. This decision was made to strengthen the validity of the findings. Consequently, all forms of literature that may not have been subjected to a rigorous review process were excluded. This exclusion criterion thus filtered out conference proceedings, book chapters, editorials, websites, and magazine articles from the sample. The English language was used as an additional inclusion criterion to avoid language bias (Dhir et al., 2020). A complete list of the inclusion/exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1.

Data collection and screening of literature

The search for keywords, abstract, and title was done in selected databases using the search string featured in Table 2. An initial search in Scopus attained 195 distinct records, including full-length articles, book chapters, conferences proceedings, review articles, and research notes. We filtered out three publications written in languages other than English. Further, after manually reviewing each record, we excluded 36 publications that were not related to BPCs and 29 publications other than peer-reviewed journal articles. This step allowed us to reduce the overall number to 76 unique records. The same research protocol was performed on the WoS database and provided an initial total of 68 records, all of which were published in English. We filtered out 24 records as they were conference proceedings, review articles, book chapters, or meeting abstracts. Subsequently, we merged the two collections and removed any duplicate records we found in the process. As a final step, we performed chain referencing to identify further relevant studies that were not found in the previous steps. We then reviewed each publication title to identify and exclude journals that could be referred to as gray literature. This brought the total number of publications to 58, which we agreed to as the definitive number to be considered for the SLR. While somewhat limited, the final sample size is in line with the standards set for management studies (Hiebl, 2021) and previously published SLRs in entrepreneurship research (Paek & Lee, 2018; Poggesi et al., 2020).

Research profiling

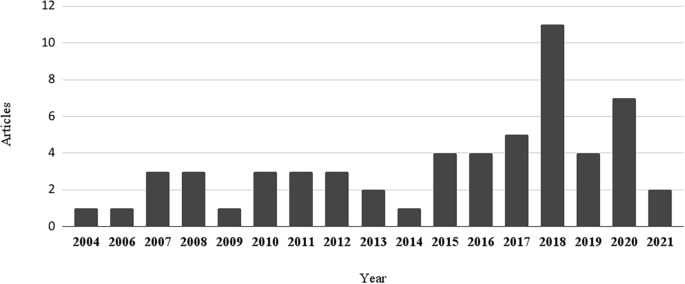

Research profiling allowed us to review the sample in terms of several descriptive statistics meant to give us a comprehensive understanding of the current state of the art of BPC research (Dhir et al., 2020). Starting with Fig. 1, we address the annual scientific production of papers included in the sample. Data suggest how BPC literature has been steady over the past two decades, with a sharp increase in recent years. The year 2018 features a significant spike in publications, with 11 distinct records to consider. These trends are in line with the consistent growth in broader entrepreneurship literature, as policymakers have shown increasing levels of interest in BPCs as effective means to create new jobs, foster innovation, and recover from economic crisis (Barbini et al., 2021).

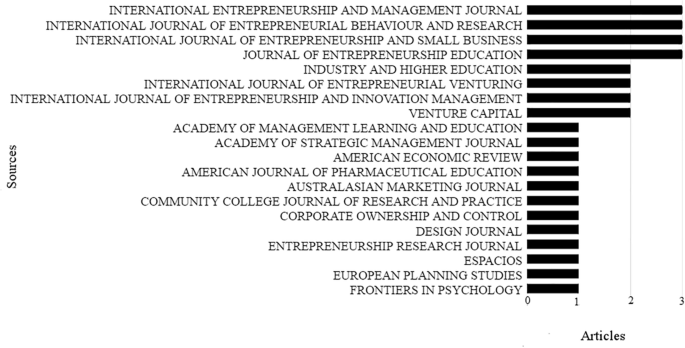

Figure 2 shows the distribution of articles throughout the various sources included in the sample. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, and International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business rank at the top.

In terms of publishing outlets, the variety of journals publishing relevant research on BPC further highlights the increasing attention scholars have devoted to this domain. Through a closer analysis, we note how leading entrepreneurship journals feature most of research articles on BPCs, thus testifying the intersection between the BPC stream and entrepreneurial education literature.

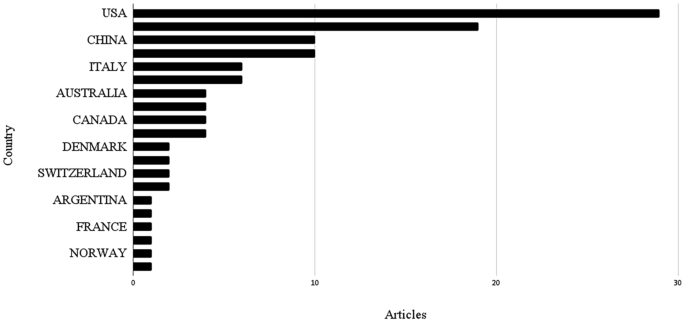

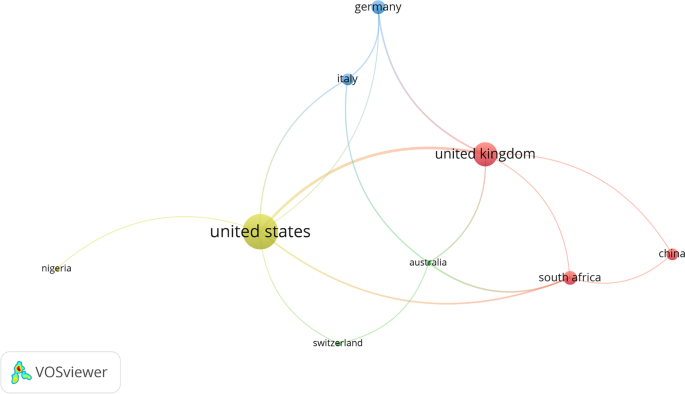

The examination of the geographic scope of the prior studies is featured in Fig. 3 and it suggests that the majority focused on a single country, with most conducted in the United States. The United Kingdom, China, and Germany also feature a significant number of publications in terms of corresponding authors’ nationality. Other countries include South Africa, Australia, Canada, Italy, Switzerland, Argentina, Brazil, France, Nigeria, and Venezuela. The above results corroborate extant research, as it sees the USA as predominant due to them being where BPC first originated (Buono, 2000), thus having a more prosperous and profound history. Consistently with previous research, we also find a solid scientific presence in Europe (Riviezzo et al., 2012; Waldmann et al., 2010) and China (Fayolle, 2013). However, developing countries are lagging, possibly because BPCs have only recently become popular there (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011).

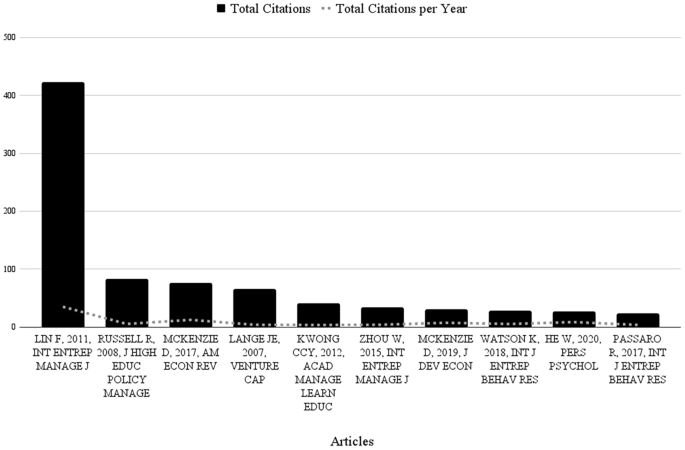

Figure 4 illustrates the top 10 most cited publications. The three most cited papers were published over a decade ago, thus acting as a theoretical foundation for development of the literature stream. More specifically, the work of Liñán et al. (2011) on factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels and education is the most cited. In their work, Liñán et al. (2011) consider and establish empathy as a necessary precursor to social entrepreneurial intentions. At the time of publication, their findings were exploratory in nature, thus prompting several additional studies to expand upon their results and further develop their conclusions.

Furthermore, the study by Russell et al. (2008) on the development of entrepreneurial skills and knowledge by higher education institutions ranks at second place. Russell et al. (2008) noted that BPCs provide fertile ground for new business start-ups and for encouraging entrepreneurial ideas. Russell et al. (2008) were among the first to suggest a positive correlation between BPCs and entrepreneurial development, thus becoming a theoretical cornerstone for studies willing to further explore the benefits of BPCs for nascent entrepreneurs (Passaro et al., 2017).

The study by Lange et al. (2007) is the third most cited work. Lange et al. (2007) supported the hypothesis that new ventures created with a written business plan do not outperform new ventures that did not have a written business plan. Their work is often cited among BPC literature when discussing theoretical assumptions against the effectiveness of business plans and, consequently, BPCs (Watson & McGowan, 2019).

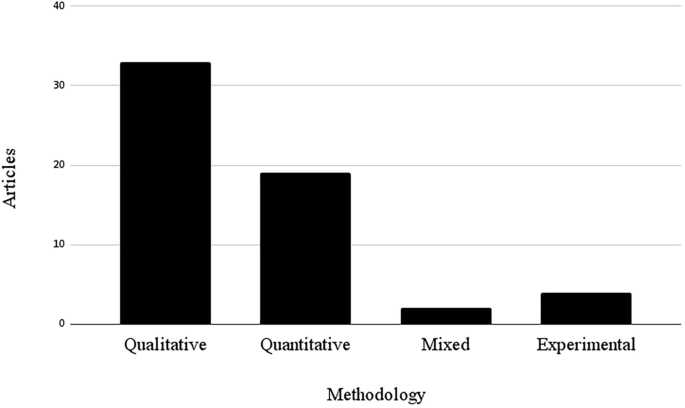

Several research methods have been adopted in the sample, both qualitative and quantitative. Figure 5 illustrates the methodological choices found within the sample, distinguished as qualitative, quantitative, mixed, and experimental research designs. The amounts shown in Fig. 5 are in absolute value and equal to n = 33 for qualitative research studies, n = 19 for quantitative research, n = 2 for mixed research, and n = 4 for experimental research. The most common choice in research design is the use of a specific BPC as a single empirical case study (Barbini et al., 2021; Efobi & Orkoh, 2018; Li et al., 2019). For instance, Jiang et al. (2018) investigated the “Challenge Cup” BPC to subsequently develop a longitudinal analysis on creative interaction networks and team creativity evolution. Similarly, Barbini et al. (2021) investigated data from a BPC in Rimini through the use of a mixed-method analysis. On the other hand, studies that focus on the educational implications of BPCs tend to use students as respondents, instead of BPC participants (Licha & Brem, 2018; Olokundun et al., 2017).

In terms of methodological choices, qualitative research on BPCs is dominated by semi-structured interviews and surveys (Burton, 2020; Watson & McGowan, 2019; Watson et al., 2018). The above is due to how in-depth, open-ended interviews fit a case study research design, thus explaining their popularity in BPC literature (Watson et al., 2015). Additionally, amid qualitative research, we find focus groups (Lu et al., 2018), fuzzy-set (Lewellyn & Muller-Kahle, 2016), content analysis, and cross-sectional research (Passaro et al., 2017). Moreover, quantitative studies include partial least squares models (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020; Overall et al., 2018), regression analysis, longitudinal studies (Jiang et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2018), and descriptive empirical research based on surveys. Partial least squares regression models are the most popular choice in regards to quantitative BPC research (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020; Overall et al., 2018), as they have allowed authors to, among other research, test the impacts of several variables on the entrepreneurial activity of BPC participants (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020) and to measure the effectiveness of universities’ promotion of entrepreneurship through events, BPCs, and incubators (Overall et al., 2018).

Figure 6 was made with the VOSviewer tool and shows the interactions between the most prolific countries in BPC literature. It showcases the co-citation network between the authors in the sample, sorted by their country of origin. In other words, countries appearing near within the diagram have closer collaboration. The size of each bubble indicates the relevance of each country within the network in terms of overall citations. Several main collaboration groups were found, each highlighted in a distinct color. Consistently with the geographical scope of the sample illustrated in Fig. 3, the UK and the USA play a predominant role in the collaboration network.

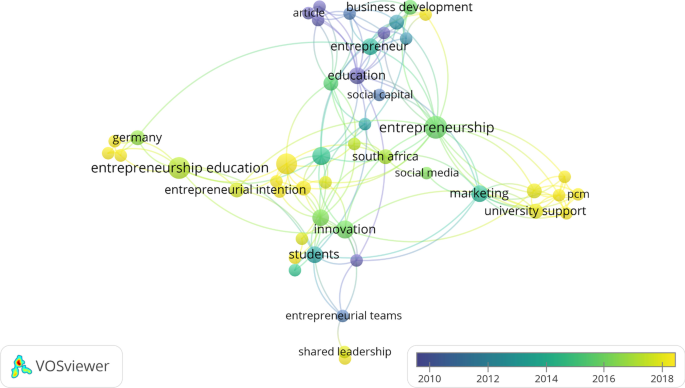

VOSviewer can also analyze the co-occurrence year between keywords. Through the co-occurrence chronology of keywords, the first co-occurrence time between keywords can be clearly displayed, which helps to understand the research in the field of BPC and how it has evolved over time. The co-occurrence chronology view is shown in Fig. 7. The color of the line between the keywords in the figure indicates the first co-occurrence time of the two. The thicker the line, the greater the intensity of the two co-occurrences and the greater the number of co-occurrences between the two keywords. We notice how the field initially started around the topic of entrepreneurial education, as highlighted by the purple and blue clusters. Progressively, the focus has shifted towards social media, business development, innovation, and marketing, most likely due to the growing relevance of digital transformation throughout the past decade.

Results

To provide readers with a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the BPC literature, we analyzed and synthesized the sample using qualitative content analysis. This technique allows researchers to identify key emerging themes from a sample and to group the records depending on their similarities (Baregheh et al., 2009). Three researchers conducted the content analysis independently to uncover the thematic structure of the sample. Later, we shared our findings and discussed divergent thoughts and interpretations. The discussion was aided by a senior researcher with relevant expertise in entrepreneurship research. After much debate, we agreed to arrange the results according to four themes: (1) BPCs as opportunities for entrepreneurial education, (2) benefits of BPC participation, (3) the ideal BPC blueprint, and (4) methodological choices and research design in BPC publications. This classification allowed for a more structured overview of the sample that also afforded enough space and detail to adequately review each literature stream. The research questions that emerged from each theme are presented in Table 3, and they could act as the backbone for future studies on the topic.

BPCs and entrepreneurial education

While entrepreneurship education existed prior to the 1960s, it only became more significant in the second half of the 20th century. Entrepreneurship education was also much more popular in the USA than in the rest of the world, due to a much greater variety of courses at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels (Dana, 1992). Greater academic interest in entrepreneurship was sparked at the beginning of the 21st century, however, and it has increased rapidly over the past two decades, in terms of both scientific publications and courses available to nascent entrepreneurs (Liñán et al., 2011).

Overall et al. (2018) emphasize the importance of universities in entrepreneurial education and BPCs. Oftentimes, universities combine traditional lectures with more practical activities, such as BPCs, to provide students with a more practically oriented schedule. Similarly, Licha and Brem (2018) highlight the tools and services available to nascent entrepreneurs via universities, including incubators, accelerators, and entrepreneurship-specific teaching methods. The findings of Licha and Brem (2018) also suggest that universities tend to give their own spin to entrepreneurial programs and that different cultures lead to different results for BPC participants and nascent entrepreneurs in general. While differences may emerge across programs based in different countries (Lewellyn & Muller-Kahle, 2016; Zhou et al., 2015), the core elements of such competitions remain stable (Parente et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurial programs have steadily increased in popularity over the past decade, thus prompting a newly found interest in BPCs as core components of said programs (Laud et al., 2015). Raveendra et al. (2018) identified several skills that universities can transfer to BPC participants, such as time management, problem solving, communication skills, and brainstorming. Although the development of these skills is not, strictly speaking, universities’ prerogative, both governments and employers want skilled entrepreneurs in society (Russell et al., 2008). Indeed, BPCs are a prime opportunity for novel entrepreneurs to develop entrepreneurial skills thanks to the potential for networking with peers and a practice-focused competitive environment. Such an opportunity appears to be tied to the historical appeal of BPCs, as they have attracted students from a plethora of disciplines and sectors throughout the decades (Russell et al., 2008).

When BPCs are approached with positive attitudes and open minds, participants can actively benefit from what they learn during their entrepreneurial journeys (McGowan & Cooper, 2008). The results of their learning experiences tend to emerge during their entrepreneurial careers, as entrepreneurial skills are held in high regard by various stakeholders and shareholders alike, including investors and business angels (Olokundun et al., 2017). Several empirical case studies strengthen these findings, illustrating the importance of BPCs as learning opportunities and their importance in terms of future entrepreneurial life (Cervilla, 2008; Li et al., 2019; Mancuso et al., 2010). It is worth mentioning that some studies in the sample had contradictory results, as universities are not always able to promote entrepreneurship with satisfactory results (Wegner et al., 2019).

However, the conversation around entrepreneurial education is still developing. For example, not much has been said about interdisciplinary personalized training and self-learning activities (Li et al., 2019). Cervilla (2008) echoes the same necessity in terms of creating and nurturing an interconnected environment around universities and spin-offs. A first set of exploratory findings suggests that the intervention of external professionals could benefit the entrepreneurial education of students; however, much remains to be said about which skills are valued the most by nascent entrepreneurs (Raveendra et al., 2018), incentives and returns for universities that host BPCs (Parente et al., 2015), and BPCs as a means to instill proactive entrepreneurial intentions in students (Olokundun et al., 2017).

Additionally, the debate surrounding the role of higher education institutions in entrepreneurial education remains very active. While universities’ support for BPCs has been proven to benefit participants in the past (Saeed et al., 2014), the findings of Wegner et al. (2019) suggest that the actions of universities have little to no impact on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Contradicting results can also be found in other studies (e.g., Coduras et al., 2016; Shahid et al., 2017), which suggests that additional research is needed to expand this literature stream further. Authors have stressed the importance of intangible benefits gained from BPCs, as participants view them as valuable learning experiences and hold the competencies gained from them in high regard, albeit not entirely useful in day-to-day routines (Watson et al., 2018). Still, on the topic of competence development, studies have highlighted that stressing the importance of specific skills during BPCs can seriously impact future entrepreneurial ventures (Overall et al., 2018).

Finally, several points of contention emerge when discussing the educational outcomes of BPCs. The literature suggests that nascent entrepreneurs rely on BPCs to refine their business ideas and get feedback (Grichnik et al., 2014; Tata & Niedworok, 2018); however, empirical and theoretical contributions to BPCs as learning experiences are limited and unclear (Schwartz et al., 2013). To address this issue, Watson et al. (2018) claim that researchers need to understand how participation in university-based BPCs affects entrepreneurial learning outcomes among nascent entrepreneurs. So far, the results have been contradictory. Fafchamps et al. (2014) found little to no impact on the growth of such entrepreneurial ventures.

Non-educational benefits of BPC participation

It goes without saying that winning a BPC implies a significant increase in visibility, which could lead to finding new stakeholders who could prove useful to the project (Parente et al., 2015). However, gray areas still exist. As Parente et al. (2015) suggest, the role of media coverage could be further improved by involving experts specialized in business and entrepreneurship, instead of generalist media alone. Competition promoters should also invest considerably more time and resources into social media promotion, as social media platforms have become more and more prominent over the years for both entrepreneurs and their potential market (Cant, 2016b; Palacios-Marqués et al., 2015). This is especially relevant for tech-savvy entrepreneurs who are active on social media platforms and could benefit from social media exposure, but they need institutions to act accordingly in this regard (Botha & Robertson, 2014). Cant (2016b) found that participants in BPCs were satisfied with the exposure they received from the event, noting that it was worth the effort. However, the author also stressed the importance of event promoters being savvy with social media promotion, which was not always the case.

More broadly speaking, BPC winners have been shown to possess a greater survival rate in entrepreneurial life due to a number of factors, including financial aid, attractiveness in the eyes of stakeholders, and a positive impact on investors (McKenzie, 2017). Additionally, McKenzie (2017) analyzed the YouWiN! competition and noted its impact on the survival rates of established firms and start-ups. The main effect of the competition was to enable firms to buy more capital, innovate more, and hire more workers, hence making the BPC an effective tool for long-term growth. The above results add to a pre-existing debate that has characterized entrepreneurship research in the past, as authors do not seem to reach a universal consensus on the perceived usefulness of business plans (Gumpert, 2003; Leadbeater & Oakley, 2001). Still, on the topic of firm survival, the results of the study conducted by Simón-Moya and Revuelto-Taboada (2016) are especially interesting for policymakers responsible for aid programs aiming to foster entrepreneurship, as they show how the quality of a business plan alone can be a necessary condition but not a sufficient condition to explain firm survival. Hence, there is a need for policymakers and institutions to foster entrepreneurship via institutional aid and programs, BPCs included.

Moreover, Fichter and Tiemann (2020) found that the promotion of sustainability in competitions leads to the integration of sustainability practices into future entrepreneurial activities. However, they warn that policymakers need to effectively plan the integration of sustainability with the entrepreneurial mindset of BPC participants, as generic sustainability orientations do not automatically lead to the integration of sustainability goals into future business activities (Cornelissen & Werner, 2014). This sentiment has been echoed in more recent research (Daub et al., 2020). The debate on the importance of BPC participation still features a few areas that have yet to be fully explored and discussed. For example, Tata and Niedworok (2018) claim that the evaluation of business plans changes throughout the phases the idea undergoes, which leads to a more prominent role of subjective feedback in the very early stages of their development. Much like business plan evaluators, nascent entrepreneurs change the way they value their competencies over time (Watson et al., 2018): what appeared most useful during their time spent educating themselves might not coincide with what is deemed most relevant during their actual entrepreneurial life; however, more evidence is required to get a proper understanding of this phenomenon.

The ideal BPC blueprint

Several studies have been conducted to explore the contexts in which BPCs thrive and the traits they need to possess to successfully shape future entrepreneurs. Cant (2018) was one of the first authors to provide a tentative blueprint for future competitions, which included a call for a more structured approach and better planning via a set of universal traits that a BPC should possess regardless of the country or culture in which it is set. Drawing on Bell (2010), Cant (2018) also stresses the importance of a go-to model as a means for inexperienced institutions to organize and manage a BPC properly without the need for previous experience.

Additionally, several common trends have emerged that could help determine a generalized BPC blueprint as accurately as possible. First, it is important to ensure that the BPC is embedded in an entrepreneur-friendly ecosystem in which both nascent entrepreneurs and professionals, such as venture capitalists, business angels, and generic investors, can interact and network with each other in a seamless way (Passaro et al., 2017). The formulation and development of a business plan is an extremely important yet delicate step for new entrepreneurs, and being able to effectively assess their opportunities and make use of feedback from established professionals is crucial (Botha & Robertson, 2014). This two-way feedback mechanism can be implemented both in the early stages of competitions via workshops and lectures and after the winner is picked so that everyone has the chance to understand their results and improve (Cant, 2018).

Cant’s (2018) blueprint stresses the importance of industry specialists aiding participants with their submissions. This finding is supported by a case study by Moultry (2011), in which industry professionals effectively participated in lectures, provided panel discussions, and helped conduct a BPC for pharmacy students. The vast majority of students who took part in the experiment claimed that the help of industry professionals significantly increased their understanding of business plans and consequently increased their chances of future entrepreneurial success. Moreover, establishing a collaboration network that ties BPC participants to industry professionals greatly increases the chances of survival for university spin-offs (Cervilla, 2008).

Finally, an effective BPC should provide winners and, when possible, participants in general with enough resources to fund the early stages of their entrepreneurial journeys (Feldman & Oden, 2007; Kolb, 2006). Funding nascent entrepreneurs through BPCs could provide several benefits that significantly increase their chances of survival, while also providing them with new opportunities, such as access to debt and equity capital (Burton, 2020). However, nascent entrepreneurs themselves need to be able to convince investors that their business ideas are worthy of their funding and resources, and in that regard, opportunity templates vary among people who occupy different professional roles (Tata & Niedworok, 2018). While expressing their concerns about founders speculating on financial rewards in the business-idea phase and proposing their own BPC evaluation framework, Tata and Niedworok (2018) call for a balanced number of jurors from each professional domain to mitigate unfair rating biases. However, much about BPC blueprints remains to be determined. Cant (2018) explains that there are no set rules applicable to all competitions and that, given the increase in popularity of BPCs all over the world, evaluating similar competitions in Europe and Asia would be a natural progression for this specific literature stream.

Methodological choices and research design in BPC publications

The BPC literature features several research design choices, with both qualitative and quantitative approaches to data collection. Generally speaking, there is a noticeable predominance of empirical research based on case studies and descriptive analysis of BPC scenarios (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018; Li et al., 2019), with little emphasis on theoretical underpinnings or theory development. Multiple longitudinal studies were identified in the sample (Mosey et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2018). We were not able to find SLRs on the topic of BPCs, other than the one performed by Tipu (2018).

From a qualitative perspective, there were several case studies from both developed (Licha & Brem, 2018) and developing countries (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018; McKenzie & Sansone, 2019). A few qualitative studies have also taken an experimental approach (Fafchamps & Quinn, 2017; Fafchamps & Woodruff, 2017), which was made possible by the availability of students and higher education institution facilities at the authors’ disposal. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in a few studies, mostly with exploratory intentions (Burton, 2020; Watson & McGowan, 2019).

Only one study can be labeled as mixed methods research (Barbini et al., 2021), whereas the remaining studies were quantitative. Methodological approaches using partial least squares regression are prevalent in BPC research (Overall et al., 2018; Wegner et al., 2019; Fichter & Tiemann, 2020) in which authors attempted to test the impacts of several variables on the entrepreneurial future of BPC participants. For example, Fichter and Tiemann (2020) used structural equation modeling to test whether the integration of sustainability goals into BPC programs affects the future business outcomes of nascent entrepreneurs, especially in terms of the inclusion of sustainability topics. Moreover, Wegner et al. (2019) applied a similar research design to determine whether universities’ role in promoting entrepreneurship contests such as BPCs positively affects students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Finally, Overall et al. (2018) used the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as a theoretical framework to measure the effectiveness of universities’ promotion of entrepreneurship through events, BPCs, and incubators.

Additionally, the topic of BPCs is multi-theoretical in nature, allowing scholars to use various theoretical underpinnings to investigate their nature. The sample features several theoretical frameworks used by authors, including screening and signaling theory for the analysis of early-stage venture-investor communication (Wales, et al., 2019); the Fishbein–Ajzen framework to predict planned behavior based on four components of reasoned action (Overall et al., 2018); institutional theory as a means to explain variation in entrepreneurial intention (Lewellyn & Muller-Kahle, 2016); and variations of the psychological model of “planned behavior” (Liñán et al., 2011). It is worth noting that while theoretical perspectives are plenty, records featured in the sample do not use multiple theoretical lenses in the same study. Finally, we find a few studies synthesize and develop their unique theoretical frameworks based on extant theory and empirical observations (Wen & Chen, 2007; McGowan & Cooper, 2008), even though a considerable portion of the sample features purely empirical results (McKenzie, 2017; Moultry, 2011).

Research gaps

Several research gaps were identified in the sample. To give a more thought-out structure to the presentation of these results, we classified the gaps into two categories: gaps related to the data and gaps related to the analysis.

Data-related gaps

A few studies had generalizability problems. The exploratory nature of some case studies presented intrinsic limitations to generalizability, as the findings were sometimes not applicable to different contexts (Cervilla, 2008; Li et al., 2019). For example, Licha and Brem’s (2018) study features two universities located in Germany and Denmark. Future research could expand upon their findings by investigating several other universities in different countries to strengthen and confirm their results.

Several studies have employed qualitative research methods using exploratory (Parente et al., 2015) or experimental approaches (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018; McKenzie, 2017). There are inherent weaknesses in such research, as self-reported surveys cannot guarantee unbiased responses (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018). Similarly, semi-structured interviews feature the same bias; however, their results can be verified with follow-up quantitative research on a larger scale (Licha & Brem, 2018; Watson et al., 2015, 2018).

Some studies were also limited due to their sample sizes. Small-scale studies are valuable for exploratory research, as they allow for an initial step into a novel investigation, but they lack in terms of representativeness (Tornikoski & Puhakka, 2009; Watson et al., 2018; Barbini et al., 2021). For example, Wegner et al. (2019) warn readers of the intrinsic limitations of small sample sizes and ask for larger-scale surveys that could potentially test and expand the results of their initial exploratory research. Moreover, Watson et al. (2018) claim that it is important to investigate other types of competitions and not limit the scope of BPC research to university-based competitions. In doing so, future research could yield new insights and even adopt comparative perspectives to determine the differences between the two worlds (Watson et al., 2018).

Gaps related to analysis

Several main gaps were identified related to analysis, including a narrow focus of prior research, limited geographic scope, and a lack of theoretical underpinnings. A few studies were conducted with very narrow foci, effectively leaving the door open for future studies to bridge the gaps they highlighted. For example, Barbini et al. (2021) focused on the educational backgrounds of nascent entrepreneurs without considering the implications of their work experience. This gap could be addressed in some capacity by future research. Furthermore, Wegner et al. (2019) point out that their research shared the same limitation, as they focused on comparing individual students’ entrepreneurial intentions rather than comparing the same individual’s intentions over time. They suggest that future research could explore the influence of universities and BPCs on students’ entrepreneurial intentions (Liñán et al., 2011).

Another issue related to the analysis was the limited geographic scope of the sample. While the BPC literature includes contributions from both developed and developing countries (Olafsen & Cook, 2016), contextual empirical evidence from both sides of the spectrum is limited. Cross-cultural analysis from different countries could lead to new findings and a more comprehensive look at the BPC phenomenon, especially in developing countries, as thus far only one study exists.

Finally, another gap identified in the sample was the lack of theoretical underpinnings in many of the studies. Most of the selected manuscripts featured qualitative case studies or empirical survey-based data (Cervilla, 2008; Li et al., 2019). Although their findings were insightful, the authors themselves note that the exploratory nature of most of the studies reflects the need for more theory-building studies on BPCs or the implementation of behavioral theories to strengthen the hypotheses developed by researchers.

Potential research areas

We identified several research areas that could be explored in the future by entrepreneurship researchers. Our selection was based on a combination of our manual review of the content included in the sample and the need for further research expressed by the authors themselves. The suggestions refer primarily to the replication of exploratory research, the need for further longitudinal research, and the testing of hypotheses and measures developed by the authors, each of which is discussed below.

Replication of exploratory studies

The lack of representativeness in the studies was the most evident and recurrent gap highlighted in the sample. Scholars could start from the preliminary research findings provided by current BPC research and replicate studies in different geographical contexts. Although BPCs share several similarities in the way they function and are managed, differences in their efficacy and the survival rate of winners and participants in general can arise. However, replicability is useful for demystifying not only the entrepreneurial lives of winners, but also BPC designs themselves. For example, the blueprint developed by Cant (2018) can be replicated and tested in several contexts to validate its effectiveness and to provide novel insights into it. Future research is required to explore this ongoing debate and to find as much information as possible on how to plan the support of professionals from outside of universities accordingly (Burton, 2020) and how they affect BPC participants’ attitudes and entrepreneurship intentions (He et al., 2020).

Longitudinal studies on BPC participants’ entrepreneurial survival

Multiple authors have called for longitudinal studies designed to follow the lives of BPC participants both prior to and after the contests take place. A few longitudinal studies already exist; however, they have also called for more studies with similar research designs. For example, Watson et al. (2018) call for longitudinal research to test the notion of competition competency they introduced in their study. Similarly, Jiang et al. (2018) claim that their longitudinal approach was severely limited by being narrowly focused on a single competition. Therefore, they call for further longitudinal studies to strengthen the validity of their findings.

Collecting longitudinal data seems to be a fitting way to contribute to BPC research, specifically, and to entrepreneurial research, more broadly, as metrics could help researchers understand the development of nascent entrepreneurial ventures over time while highlighting the effects of factors such as entrepreneurial education or institutional support for BPC participants at the beginning of their journeys (Wegner et al., 2019). Currently, little research has been conducted on a longitudinal basis; thus, there is still a severe lack of understanding of BPCs’ impacts on the entrepreneurial teams and businesses that emerge from them (McGowan & Cooper, 2008).

Utilization of diverse research methods

Scholars could make use of a more diverse set of research methods in future BPC studies to overcome the paucity of theoretical contributions and quantitative research in general. While several exploratory studies serve as a strong starting point for BPC research (Burton, 2020; Parente et al., 2015), it is important to approach the topic in a more multidisciplinary manner, for instance, by including more mixed-method studies in the future (Barbini et al., 2021). This could lead to more comprehensive results and a more holistic understanding of the BPC literature among academics and practitioners (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018).

Diverse theoretical perspectives

Little theory is currently available on BPCs (Cant, 2018). Although multi-theoretical in nature, BPC literature draws on a limited number of existing theories, such as the quadruple-helix model (Parente et al., 2015) and the TPB (Overall et al., 2018). While the results from exploratory research are interesting and valuable, most of these studies are not underpinned by theory or theoretical frameworks of any kind. Furthermore, the paucity of theoretical underpinnings in our sample can be used as a prompt for future research. To date, only a few studies have grounded their research in established theories (Lv et al., 2021; Overall et al., 2018). Future research could try to bridge this gap, especially with behavior-centered theories and frameworks, which could be used to address several research questions in terms of BPCs’ impacts on future entrepreneurial lives and the way nascent entrepreneurs incorporate what they learn during competitions into their everyday professional practice (Watson & McGowan, 2019).

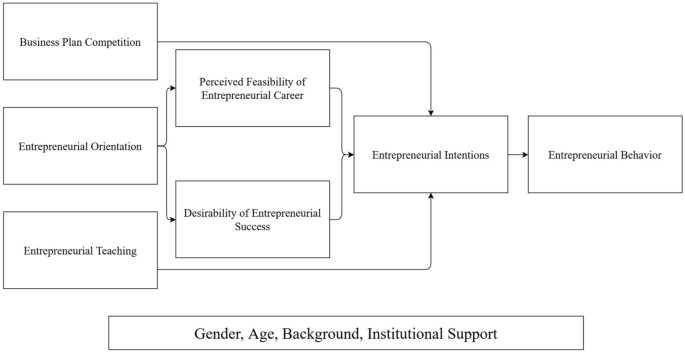

Theoretical framework

After reviewing the theoretical underpinnings found within the sample, we find a predominance of the conceptual framework developed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), namely the theory of reasoned action (TRA), which allows for a systematic theoretical orientation on beliefs and attitudes to perform a certain behavior. By using the TRA as a base reference, we synthesized extant theoretical research found in the BPC literature. We listed several independent and dependent variables depicted in previous work, reviewed the connections found between them, and illustrated the role played by moderating variables. The framework also serves as a reference to determine the impact each factor has on BPC participants in their entrepreneurial futures. The framework is illustrated in Fig. 8.

In the context of BPC, several antecedents can be identified as determinants of future entrepreneurial behavior. Our framework draws on previously published theoretical underpinnings to define both the antecedents of entrepreneurial activity and the multiple intrinsic factors that contribute to its multifaceted nature. We start by identifying entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial competence, which have been investigated in the literature through the theoretical lens of the TPB (Ajzen, 1991). Then, drawing on the theoretical model Lv et al. (2021) developed, we expect entrepreneurial teaching and practice support to positively impact future entrepreneurial intention and the development of entrepreneurial competencies. This theoretical assumption is backed by a few studies (Liñán et al., 2011) and deemed worthy of further attention. For example, future research could adopt a hierarchical multiple regression to determine the impact of entrepreneurial teaching on future entrepreneurial intention (Olokundun et al., 2017). Alternatively, the impact could be investigated through multiple regression models by developing a set of factors tailored to the entrepreneurial education programs and extracted via questionnaires (Liñán et al., 2011).

Drawing on entrepreneurial research, we find the perceived desirability of entrepreneurship and the perceived feasibility of entrepreneurship (Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014) as the two main attitudes toward entrepreneurial intentions (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). In other words, per the theoretical model proposed by Overall et al. (2018), entrepreneurial orientation leads students and nascent entrepreneurs to the desirability of an entrepreneurial career and the perceived feasibility of said career, which subsequently influence their entrepreneurial intentions. Then, drawing on the TRA and TPB frameworks, we propose that when individuals possess strong desirability toward an entrepreneurial career and perceive said career as feasible, they will most likely form entrepreneurial intentions (Overall et al., 2018).

We define entrepreneurial teaching as the essential aspect of entrepreneurship education. Research suggests that educational support affects nascent entrepreneurs by providing them with adequate skills to tackle better entrepreneurial life (Grichnik et al., 2014; Tata & Niedworok, 2018). In other words, entrepreneurial education programs actively contribute to entrepreneurial development (Škare et al., 2022). The positive effects of educational support on entrepreneurial success and intention can be found in empirical studies (Thomas et al., 2014; Passaro et al., 2020). More specifically, we note entrepreneurial education as a key factor in influencing innovation and development. The entrepreneur’s competencies are seen as an individual and organizational resource that needs to be properly developed through educational programs in order to bring out its potential for the entrepreneurial future (Salmony & Kanbach, 2022). Overall, drawing on the theoretical framework of Lv et al. (2021), we find both entrepreneurial teaching and entrepreneurial practice, intended as BPC participation, to affect their entrepreneurial intention significantly.

A set of moderating control variables can be used to provide a more comprehensive overview of the influence played by the stakeholders mentioned above. Wegner et al. (2019) suggest that future research could specify how age moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial support variables and the outcomes of BPC participants. Other studies have also supported the use of age as a moderator of the effectiveness of BPC support on entrepreneurial intention (Cant, 2018; Passaro et al., 2020). Furthermore, McGowan and Cooper (2008) claim that entrepreneurs’ levels of knowledge could be tested as moderating variables of entrepreneurial intention and behavior, as BPC participants might have different backgrounds and levels of expertise, which could influence the outcomes of their entrepreneurship activities. Additionally, Lewellyn and Muller-Kahle (2016) propose using gender as a moderator of entrepreneurial activity. Finally, Terán-Yépez et al. (2022) discuss the use of affective dispositions as variables influencing entrepreneurial activity. Future research could expand upon their findings and use hope, courage, fear and regret as moderating variables of entrepreneurial intentions.

Entrepreneurial intention as a variable that affects entrepreneurial behavior is backed by a theoretical study conducted by Overall et al. (2018), underpinned by the TPB (Ajzen, 1991). A positive correlation between the two was deemed consistent and statistically significant. In conclusion, the above framework could help explore the connection between BPC participation and the development of entrepreneurial activity, which thus far has received little empirical attention in research. Future research could delve further into the impact of BPC participation and institutional support on entrepreneurial activity to give proper closure to a long-lasting debate on the usefulness of BPC as a stimulant for entrepreneurial practice (Fayolle & Klandt, 2006; Russell et al., 2008). In addition, many methodological approaches could effectively encapsulate the impact described above, as seen in entrepreneurship research. For instance, future studies could employ a longitudinal case study approach (Overall et al., 2018) to follow nascent entrepreneurs in their journey and determine the impact of BPC participation. Longitudinal studies have proven effective in capturing the factors and variables influencing entrepreneurial life over the years (Petty & Gruber, 2011).

Conclusions

The purpose of this SLR was to critically analyze the literature related to BPCs and set the future research agenda for the area of entrepreneurship. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first SLR to review research focused on recent BPC literature (Tipu, 2018), thus making our contribution original in its approach. The originality of the study lies in it being the first attempt at conducting an SLR on the topic of BPCs and contributing to science in several ways, as depicted below. Our study on BPC research has several implications for both academics and practitioners. From a theoretical perspective, our study makes several contributions to BPC and entrepreneurship literature. It does so by not only synthesizing extant research, but also by providing a structured research agenda built upon the several gaps found amid BPC literature. A further contribution to science is the development of a theoretical framework that will enable future researchers to have a bird’s-eye view of the domain and structure their future contributions accordingly. From a practical perspective, the study is of interest to practitioners and nascent entrepreneurs, as it provides policymakers and practitioners with a BPC blueprint featuring state-of-the-art characteristics and several key implications on how and why participating in BPCs is beneficial to nascent entrepreneurs. We propose a more detailed look at both theoretical and practical implications below.

Implications for research

Our main research contribution is a detailed review of the recent literature on BPCs, which can be deemed original, as no authors have attempted to systematically synthesize the existing BPC research. Our approach to the design of the SLR was twofold. We first provided a descriptive overview of the sample in terms of annual scientific production and geographical relevance. We then applied qualitative content analysis to highlight key emerging themes that were used to identify foci for future research directions. Based on our classification, we contend that the theoretical advancement of this research area requires greater attention to both antecedents and consequences of BPC attendance.

Our second contribution was the development of a research framework to synthesize existing knowledge on BPCs and to provide new and original insights into the BPC literature stream. Our framework explicates the role played by BPCs in the professional lives of nascent entrepreneurs (McKenzie, 2018; Overall et al., 2018) in terms of how it affects their entrepreneurial behavior (Burton, 2020; Passaro et al., 2017) and identifies the specific characteristics BPCs should feature to be as effective as possible. The same framework also helps define the scope for future research, as it identifies several avenues that future entrepreneurship scholars should explore (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020; Li et al., 2019). The framework provides future researchers a bird’s-eye view of the existing knowledge base in the area, indicating, at the same time, what remains underexplored or ignored. Additionally, by profiling extant research on BPCs, we offer scholars a comprehensive overview of potentially appropriate outlets for their studies, along with the most widely used methods and theories that could help them design their future research.

Finally, we contribute by systematically uncovering crucial research gaps in the reviewed literature on BPCs from both a methodological and a content perspective. From a methodological perspective, our analysis has revealed the need for future research to broaden the methodological scope of BPC research (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018). Thus far, the BPC literature stream has been dominated by empirical research featuring case studies and experimental designs (Cervilla, 2008; Li et al., 2019; Mancuso et al., 2010). Quantitative and mixed-method research is needed to further expand upon the findings of exploratory BPC research and to test their validity on a larger scale. From a content perspective, our study has defined a structured research agenda synthesized from extant gaps. We have identified and listed several research questions that could drive future work on the topic. Additionally, our study has highlighted the uneven distribution of BPC research from a geographical standpoint. While their significance is equally pertinent for developed and emerging economies (Tipu, 2018) and BPC programs are becoming increasingly popular in developing countries (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011; Wong, 2011), our findings suggest that country-specific production is still lagging behind pioneering nations, namely the USA and the UK. Hence, there is a need for additional evidence from developing countries, along with cross-cultural analyses to highlight the cultural differences in BPC and entrepreneurial education.

Practical implications

Our study has multiple implications for BPC practices. First, it provides policymakers and practitioners with a BPC blueprint featuring state-of-the-art characteristics. Drawing on Cant’s (2018) BPC blueprint, which was an attempt to identify an ideal set of characteristics for BPCs, we reviewed and expanded upon their findings by adding new points of view taken from empirical studies found in our sample to add new insights and incorporate more contributions from the literature. Overall, the ideal BPC should feature active participation from industry professionals, as they can provide participants with valuable insights into the professional world (Botha & Robertson, 2014), which BPC research has shown to be important (Moultry, 2011). Furthermore, a serious effort should be made to guarantee BPC participants funds and financial resources for the early stages of their entrepreneurial lives, as material support and knowledge sharing are both crucial to increasing their chances of survival (Burton, 2020; Passaro et al., 2017).

Second, our study informs practitioners of the importance of longitudinally monitoring BPC participants throughout their entrepreneurial lives (Watson et al., 2018). Longitudinal data allow a better understanding of the factors and variables influencing entrepreneurial life (Petty & Gruber, 2011). This could help BPC organizers better weigh the design choices in their educational courses by monitoring the returns they get from the seeds planted during the developmental phase of nascent business ideas (Jiang et al., 2018). Longitudinal monitoring of BPC participants is valuable in several ways. As suggested by McKenzie (2017), BPC winners tend to possess a greater survival rate in entrepreneurial life, which contributes to the debate on whether the quality of business plans affects the future survival rate (Simón-Moya & Revuelto-Taboada, 2016). Practitioners and policymakers should be asked to monitor and support BPC participants after the competition. As noted by Cant (2018), building a long-lasting collaboration with BPC participants increases their chances of survival, regardless of whether they have won the actual competition. The role played by BPC organizers in building a post-competition collaborative network is vital and has a significant impact on the survival rate, employment, profits, and sales of ventures participating in BPCs (McKenzie, 2017).

Our study could also be beneficial to managers, entrepreneurs, and professionals alike, as it can provide them with several key implications on how and why participating in BPCs is beneficial to nascent entrepreneurs, in terms of visibility, knowledge development, and networking opportunities (Thomas et al., 2014; Passaro et al., 2020). This is true both for novel entrepreneurs who have yet to emerge and for industry professionals who are willing to get in touch with future generations of entrepreneurs and stimulate the discussion around the topic of BPCs (Barbini et al., 2021). While participants generally obtain more tangible benefits from winning BPCs, their very participation in the competition can provide several intangible benefits as well, primarily in terms of networking opportunities and skill development. In this regard, our study is of practical significance for nascent entrepreneurs willing to partake in BPCs, as it features a clear depiction of what to expect to gain from the competition.

Limitations and future research

We adopted an SLR methodology to analyze the available research on BPCs. Our systematic review of the BPC literature provided descriptive and original contributions to the field. Four research questions were addressed in this article. RQ1 was addressed by providing an overview of the current state of the art of BPC research in what we refer to as research profiling. Fifty-eight unique records were extracted from the Scopus and WoS databases and analyzed in terms of annual scientific production, publication sources, geographical contexts, and influence in terms of citations. We addressed RQ2 by adopting qualitative content analysis and identifying several emerging themes across the sample, which led to a structured overview of the existing knowledge on BPCs. In regards to RQ3, we were able to identify several research gaps in the empirical literature and suggest avenues for further research. Finally, we addressed RQ4 by developing a theoretical framework that uses the above sample as its foundation. The framework aims to investigate the multidimensional nature of BPCs and provide future researchers with a theoretical underpinning for their studies.

In regards to future research directions, our systematic review has highlighted several thematic areas of prior research and investigated extant gaps both in terms of topics and in terms of methodological choices. We have, thus, identified various possible avenues for future research and presented them in a theoretical framework, that acs as a synthesized view of the existing research, serves as the basis for identifying visible gaps in prior research and suggesting various theme-based research questions and avenues of future research. In other words, the framework aims to investigate the multidimensional nature of BPCs and provide future researchers with a theoretical underpinning for their studies.

There are a few caveats worth mentioning regarding this study, some of which are intrinsic to the SLR methodology. First, the sample may not have included a few records that did not appear in the online repository due to missing or different keywords. Although chain referencing reduces the chances of this happening, the risk is still there and needs to be addressed. Second, our research protocol included only peer-reviewed journal articles written in English, as conference proceedings, book chapters, and review articles were excluded from the sample. Future research could include gray literature and other sources to compare their results with those published in peer-reviewed journals. Third, the scope of the SLR was limited to BPCs. Therefore, it did not explore nascent entrepreneurs or the role of entrepreneurial education in universities in general, despite both topics being strongly related to BPCs. Future SLRs could take a broader approach and discuss the topic of entrepreneurial education, to which the BPC stream contributes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

* Articles included in the sample of the Systematic Literature Review

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

* Arranz, N., Ubierbna, F., Arroyabe, M. F., Perez, C., & De Arroyabe, J. C. (2017). The Effect of Curricular and Extracurricular Activities on University Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention and Competences. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 1979–2008.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Desai, S. (2022). The role of institutions in latent and emergent entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121263

* Barbini, F. M., Corsino, M., & Giuri, P. (2021). How do universities shape founding teams? Social proximity and informal mechanisms of knowledge transfer in student entrepreneurship. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(4), 1046–1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-020-09799-1

Baregheh, A., Rowley, J., & Sambrook, S. (2009). Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation. Management Decision, 47(8), 1323–1339. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910984578

* Bell, J. (2010). Student business plan competitions: Who really does have access? Moyak.com. Retrieved October 19, 2022, from http://www.moyak.com/papers/student-business-plan.pdf

* Botha, M., & Robertson, C. L. (2014). Potential entrepreneurs’ assessment of opportunities through the rendering of a business plan. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 17(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v17i3.524

* Brentnall, C., Rodríguez, I. D., & Culkin, N. (2018). Enterprise Education Competitions: A Theoretically Flawed Intervention. In D. Higgins, P. Jones, & P. Mcgowan (Eds.), Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research (pp. 25–48). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Buono, A. F. (2000). A review of Stuart crainer and Des dearlove’s gravy training: Inside the business of business schools. Business and Society Review, 105(2), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/0045-3609.00083

* Burton, J. (2020). Supporting entrepreneurs when it matters: Optimising capital allocation for impact. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 9(3), 277–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/jepp-06-2019-0054

* Cant, M. C. (2016a). Entrants and winners of a business plan competition: Does marketing media play a role in success? Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 19(2), 98–119.

* Cant, M. C. (2016b). Using social media to market a promotional event to SMEs: Opportunity or wasted effort? Problems and Perspectives in Management, 14, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.14(4).2016.09

* Cant, M. C. (2018). Blueprint for a business plan competition: Can it work? Management Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 23(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.30924/mjcmi/2018.23.2.141

* Cervilla, M. A. (2008). Celulab case: A “spin-off” de technoclinical solutions.

* Clingingsmith, D., Drover, W., & Shane, S. (2022). Examining the outcomes of entrepreneur pitch training: An exploratory field study. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00619-4

Coduras, A., Saiz-Alvarez, J. M., & Ruiz, J. (2016). Measuring readiness for entrepreneurship: Aninformation tool proposal. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 1(2), 99–109.

Connell, R. (2013). The Neoliberal Cascade and Education: An Essay on the Market Agenda and its Consequences. Critical Studies in Education, 54, 99–112.

Cornelissen, J. P., & Werner, M. D. (2014). Putting framing in perspective: A review of framing and frame analysis across the management and organizational literature. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 181–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.875669

Dana, L. P. (1992). Entrepreneurial Education in Europe. Journal of Education for Business, 68(2), 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.1992.10117590

* Daub, C. -H., Hasler, M., Verkuil, A. H., & Milow, U. (2020). Universities talk, students walk: Promoting innovative sustainability projects. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijshe-04-2019-0149

Dee, N., Gill, D., Weinberg, C., & Mctavish, S. (2015). Start-up Support Programmes: What’s the Difference? NESTA.

Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., & Malibari, A. (2020). Food waste in hospitality and food services: A systematic literature review and framework development approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 270, 122861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122861

* Efobi, U., & Orkoh, E. (2018). Analysis of the impacts of entrepreneurship training on growth performance of firms: Quasi-experimental evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 10(3), 524–542. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-02-2018-0024

Fafchamps, M., McKenzie, D., Quinn, S., & Woodruff, C. (2014). Microenterprise growth and the flypaper effect: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 106, 211–226. Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.09.010

* Fafchamps, M., & Quinn, S. (2017). Aspire. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(10), 1615–1633. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1251584