Abstract

The personality traits that define entrepreneurs have been of significant interest to academic research for several decades. However, previous studies have used vastly different definitions of the term “entrepreneur”, meaning their subjects have ranged from rural farmers to tech-industry start-up founders. Consequently, most research has investigated disparate sub-types of entrepreneurs, which may not allow for inferences to be made regarding the general entrepreneurial population. Despite this, studies have frequently extrapolated results from narrow sub-types to entrepreneurs in general. This variation in entrepreneur samples reduces the comparability of empirical studies and calls into question the reviews that pool results without systematic differentiation between sub-types. The present study offers a novel account by differentiating between the definitions of “entrepreneur” used in studies on entrepreneurs’ personality traits. We conduct a systematic literature review across 95 studies from 1985 to 2020. We uncover three main themes across the previous studies. First, previous research applied a wide range of definitions of the term “entrepreneur”. Second, we identify several inconsistent findings across studies, which may at least partially be due to the use of heterogeneous entrepreneur samples. Third, the few studies that distinguished between various types of entrepreneurs revealed differences between them. Our systematic differentiation between entrepreneur sub-types and our research integration offer a novel perspective that has, to date, been widely neglected in academic research. Future research should use clearly defined entrepreneurial samples and conduct more systematic investigations into the differences between entrepreneur sub-types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Small businesses form a vital part of the global economy and constitute the majority of ventures in most regions (Mazzarol and Reboud 2020). By creating new small businesses, entrepreneurs effect economic growth and development in their communities (Stel et al. 2005; Bosma et al. 2018). To promote entrepreneurial activity and provide support to small businesses, an understanding of what characterizes those who found and manage such businesses is required (Shane 2003). As such, academics and policymakers alike are interested in determining how entrepreneurs’ personality traits differ from those of the general population.

Before we can characterize entrepreneurs in terms of their personality traits, we must first define the term “entrepreneur”. While entrepreneurship research has expanded significantly, it remains fragmented in its approaches and definitions (Ferreira et al. 2019). Consequently, entrepreneur classifications span a vast number of definitions (Chell et al. 1991) that rarely overlap (Wickham 2006). Accordingly, studies have based their research on a variety of samples of subjects that can all technically be classified as entrepreneurs. In truth, however, these samples vary substantially. For example, some studies on entrepreneurial personality traits examine founders of technology-based enterprises (Roberts 1989), some define entrepreneurs as local farmers (Mubarak et al. 2019) and others survey nursing students as potential entrepreneurs (Ispir et al. 2019). While these exemplary subjects can all be classified as “entrepreneurs” in the broadest sense, as disparate entrepreneur sub-types they are likely more different than similar. At the same time, mandating a single unified definition of “entrepreneur” would limit the insights gained from different samples. Instead, a clear differentiation between entrepreneurial sub-types should be made to provide concrete insights into the traits of various types of entrepreneurs.

Several previous literature reviews (e.g. Jennings and Zeithaml 1983; Johnson 1990; Stewart and Roth 2001, 2007; Collins et al. 2004; Zhao and Seibert 2006; Zhao et al. 2010; Brandstätter 2011; Kerr et al. 2018; Newman et al. 2019) have summarized insights into entrepreneurial personality traits that have been made across academic research. However, to our knowledge, none have systematically and fully differentiated between the types of entrepreneurs sampled in their included studies as part of their main review.Footnote 1 Further, several literature reviews have incorporated studies that themselves differed in their use of the term “entrepreneur”. Thus, different entrepreneurial samples were used in the individual studies and integrated without further differentiation in the reviews. It is, however, questionable whether the results of the studies referenced in the reviews are directly comparable if they used different entrepreneur sub-types. Beyond this, some reviews have included studies that tested samples of non-entrepreneurs but did not highlight this in their review. For example, students with entrepreneurial interest are frequently used as samples in studies investigating entrepreneurial personalities, and these results are often included in reviews, despite these students not yet being practicing entrepreneurs. Last, as every review has set out to characterize entrepreneurs based on marginally different or nonexistent entrepreneur definitions, their sets of included studies have differed. Taken together, while these literature reviews offer important insights into the personality traits of entrepreneurs in the broadest sense, they do not enable us to make inferences about different sub-types of entrepreneurs.

The aim of this study is to systematically examine previous research on entrepreneurs’ personality traits while actively differentiating between the types of entrepreneurs analyzed in each study. We integrate information from 95 papers to explore whether inconsistencies in their findings can be explained by definitional variation and to examine whether there are personality differences across entrepreneur sub-types. However, we do not aim to divide the previous research by strict definitional categories of entrepreneurs. Instead, we make inferences from the entrepreneur sub-type examined and outline potential gaps in the literature where differentiation in entrepreneur types has yet to be made clear. To do this, we apply the guidelines offered by Kraus et al. (2020) to conduct a systematic literature review (Tranfield et al. 2003) of studies on entrepreneur characteristics while focusing on what their findings reveal about different sub-types of entrepreneurs.

This study has several benefits for academic research on entrepreneurs’ personality traits. It offers novel insights into more specific entrepreneur categories by actively differentiating many entrepreneur types and evaluating the variation in entrepreneur samples. Furthermore, this literature review helps to disentangle which personality traits are associated with entrepreneurial interest, venture creation, and entrepreneurial success, depending on the type of entrepreneur sampled. For example, the personality factors that facilitate venture success may vary by entrepreneur or company type. From a hypothetical perspective, the success of a second-generation microenterprise may rely on Conscientiousness while that of an aggressively growth-oriented, early-stage start-up may depend on Innovativeness and Risk-taking propensity.

We pursue three main research objectives throughout this review. First, we investigate whether previous research on entrepreneurial personalities has varied in its definition of the term “entrepreneur” in the way we assumed. Second, we examine whether there are inconsistent findings in previous research. Without being able to infer causality from a literature review, we propose that one potential explanation for such inconsistencies is the use of different definitions of entrepreneur. Third, we note the personality differences between entrepreneur sub-types in the few studies that differentiate between them.

2 Systematic literature review methodology

This study used the systematic literature review methodology from Tranfield et al. (2003). We first set out to gain an overview of the field and to define our research objectives in an inductive pre-analysis. As the number of personality traits for investigation was potentially infinite, the choice must inherently be limited. A selection of traits was obtained through an inductive pre-analysis of the commonly measured personality traits in research on entrepreneurs: (1) the Big Five (Zhao and Seibert 2006; Zhao et al. 2010; Kerr et al. 2018), (2) Need for Achievement (nAch; Rauch and Frese 2007; Stewart and Roth 2007), (3) Innovativeness (Kerr et al. 2018), (4) Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE; Miao et al. 2017; Newman et al. 2019), (5) Locus of Control (LOC; Jennings and Zeithaml 1983), and (6) Risk attitudes (Stewart and Roth 2001).

Based on this pre-analysis, these six most common personality traits formed the main component of our search string (“Appendix 1”), which we iterated in feedback loops among our working group. As recommended by Kraus et al. (2020) for entrepreneurship literature reviews, we restricted our search to online databases and journal articles, and excluded books, conference papers and conference proceedings.

We applied our search string and received an initial sample of 1453 publications from the Web of Science (1367), JSTOR (19) and ScienceDirect (67) databases. A set of 34 papers was excluded because the papers were not retrievable in full text to us. The quality of the remaining papers was reviewed based on the corresponding journal rankings. For this, we applied the conversion table of academic journal rankings (Kraus et al. 2020), and the journals with at least a C-rating in VHB JQ3 or the equivalent in ABS (≥ 2) or JCR IF (≥ 1.5) were included. This quality gate led to the exclusion of further 799 papers. After careful consideration, 4 papers that were lower than the defined quality threshold were reincluded because of their importance to our research question. We thoroughly checked for methodological or sampling concerns in the four papers, took note of any potential drawbacks we observed but did not note any of major significance. Next, all abstracts were reviewed, and 529 papers were excluded because they did not contribute to answering our research objectives, as outlined in the introduction.

Our final sample consisted of 95 papers,Footnote 2 of which 14 were literature reviews or meta-analyses, and 81 were empirical studies. We checked whether the 14 literature reviews outlined papers similar to the 81 empirical studies identified in our literature review and found a comprehensive overlap. This showed us that we had likely not missed or erroneously excluded any relevant papers. Our final sample was transferred into an Excel data extraction form that we used to analyze the information by personality trait and entrepreneur sub-type investigated.

This review aims to provide novel insights by clearly differentiating between the definitions of the term “entrepreneur” used in studies on entrepreneurial personality traits. As already outlined, we examined six different personality traitsFootnote 3 across the six sections of our review. The distribution of the included literature reviews and meta-analyses and empirical studies across the six personality traits is outlined in Fig. 1. Please note that the sum of the analyzed empirical studies and literature reviews was 95, but several of the studies and reviews elucidated more than one personality trait.

Our approach for the remainder of our literature review is the following. After the introduction and methodology sections, we outline our insights for each of the six personality traits and, in a second part, summarize our findings per entrepreneur sub-type. Here, we show personality differences and similarities between individual entrepreneur sub-types. Finally, we discuss our findings.

3 Integrated insights per personality trait

The papers summarized in our literature review covered all six personality traits: the Big Five, Need for Achievement, Innovativeness, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and Risk attitudes.

As outlined in the introduction, previous literature reviews and meta-analyses on entrepreneur personalities have frequently relied on different definitions of the term “entrepreneur”. This has resulted in empirical studies with different entrepreneurial samples being included in reviews without further differentiation and consequently the comparison of potentially incomparable samples. Similarly, empirical studies on entrepreneur personalities have rarely shared the same definition of “entrepreneur”. In our literature review, we first set out to retrieve the various definitions of “entrepreneur” used in previous research. An exemplary selection of the definitions of entrepreneur samples in previous research is shown in Table 1.

In the following sections, we will conduct an in-depth review of the findings from our literature review. We first review entrepreneur definition differences for the six personality traits examined, and in a later part, we draw general inferences and characterize a selection of entrepreneur sub-types.

3.1 The Big Five

3.1.1 Preface: concept introduction

The “Big Five” (Goldberg 1990; McCrae and John 1992) is a common classification system of personality traits. It is a replicable and robust methodology for grouping thousands of potential personality descriptors (Ostendorf and Angleitner 1994) while maintaining generalizability across samples and methodologies (John and Srivastava 1999). As the name states, the Big Five consists of five categories: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Openness to Experience.

The Big Five taxonomy of personality traits dates back more than 70 years (Fiske 1949). Originally, little academic consensus around which personality traits were part of it resulted in different researchers applying a variety of personality traits in their research. Consequently, this methodological variance led to contradictory findings. In the 1980s, this lack of methodological consensus resulted in a widespread view that the relationship between entrepreneurial behavior and personality traits was overrated and should not be investigated further. The re-emergence of the Big Five taxonomy in the 1990s (Costa and McCrae 1992a, b) enabled researchers to conduct more systematic investigations into the relationship between personality and entrepreneurial activity. Since then, academic interest in entrepreneurs’ personality traits has resurfaced, with the Big Five at the center of the discussion.

3.1.2 Integrated insights from our review

From our review, we drew two main insights regarding the use of various samples in previous research on the Big Five traits of entrepreneurs. These were on the use of different entrepreneur sub-types across research to date, and second, on the extensive use of non-entrepreneurial samples in previous research on entrepreneurial personalities.

First, we observed that different entrepreneur sub-types were tested as samples when the Big Five personality traits were investigated. Simultaneously, we observed some discrepancies in the findings, regarding Extraversion and Agreeableness in particular. For example, regarding Agreeableness, we observed a breadth of entrepreneurial definitions and simultaneously different findings regarding personality traits. Despite this, few studies directly compared different entrepreneur sub-types in the Big Five. One example is Antoncic et al. (2015) who sampled non-entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs along the founding process. While the practicing entrepreneurs were lower in Agreeableness than the non-entrepreneurs, potential entrepreneurs with entrepreneurial interest—but who had not already founded—were the lowest in Agreeableness of all. Without being able to infer causality, this may offer a hypothesis why some studies who use non-founding students with entrepreneurial interest as a proxy for actual entrepreneurs observe no correlation between Agreeableness and entrepreneurial intent (Chan et al. 2015; Mei et al. 2017). A further example is Yang and Ai (2019) who showed differences in all five of the Big Five personality dimensions between self-employed and agrirural entrepreneurs. Whilst these observations are merely exemplary, they indicate that previous research has applied a span of entrepreneurial definitions and that results differ depending on the sub-type analyzed. This demonstrates that outcome variation can co-occur with definitional differences. Despite these definition-dependent discrepancies, few empirical studies tested them through direct comparisons of entrepreneur sub-types.

Although we cannot infer causality, it is possible that the variability in these findings was due to the differences in the entrepreneur types sampled in the individual studies. It is important to differentiate between entrepreneurial types, as it may explain the existing discrepancies. Future research differentiating more between different entrepreneur types will likely reveal that the Big Five personality traits vary by business form, environment, and entrepreneur type. For example, we hypothesize that Agreeableness is more important in larger organizational settings, which require a high level of coordination with peers, than in self-employment settings. Similarly, we hypothesize that Extraversion is more important for entrepreneurs in settings with considerable interpersonal exchange with many stakeholders than for those engaging in individual labor.

As our second main insight, we noted that non-entrepreneurs were frequently tested in previous entrepreneurship personality research. While the use of these non-entrepreneurial groups is valid to investigate entrepreneurial interest, the findings may not be directly transferable toward the personality traits of practicing entrepreneurs. Although interest may be an important determinant of later behavior (Ajzen 1991), personality differences may exist between those who are entrepreneurially interested and those who act on this interest by founding a venture. Outside of the entrepreneurial domain, research has sometimes observed merely week correlations between interest and behavior that are below practical significance (Rhodes and Dickau 2012). Because of this, it becomes particularly important to clearly differentiate between entrepreneurially interested samples and practicing entrepreneurs. In our review, we observed that several studies examined the Big Five across two types of non-entrepreneurial samples. First, the largest group of studies on entrepreneurial interest involved college or university students (e.g. Chan et al. 2015; Mei et al. 2017), likely due to the accessibility of student samples. It is, however, questionable whether students with entrepreneurial interest can truly shed light on the personalities of practicing entrepreneurs, as they have not yet founded a business and have entrepreneurial interest at most. Second, scientists and academics were sometimes used as entrepreneur proxies (Obschonka et al. 2012). While these insights about entrepreneurial activity in a specific subset of non-entrepreneurs are highly valuable to research per se, they cannot offer the full depth of insights about practicing entrepreneurs in general, due to the samples’ inherent focus on entrepreneurial interest.

3.1.3 Summary: the Big Five

Our study supports the findings of earlier reviews regarding entrepreneurs’ Big Five traits (high Openness to Experience, high Conscientiousness, low Neuroticism), including the mixed results regarding Agreeableness and Extraversion. To our knowledge, previous reviews have not systematically differentiated between entrepreneur sub-types in their main analyses. In addition, empirical studies have applied vastly different definitions in selecting their entrepreneurial samples and simultaneously show somewhat inconsistent results. When we classified the studies in our review based on their definition of the term “entrepreneur,” the results became more consistent. We cannot make any inferences about causality from our review. However, the differences in entrepreneurial definitions constitute a promising hypothesis regarding the previous inconsistencies, which we encourage future research to pursue. Furthermore, we observed that previous research tended to rely upon non-entrepreneurial samples to investigate the personality traits of entrepreneurs. We encourage future research toward differentiation in entrepreneur types and toward the more widespread use of samples of actually practicing entrepreneurs.

3.2 Need for Achievement

3.2.1 Preface: concept introduction

Need for Achievement (nAch; Murray 1938; McClelland et al. 1953) is a multidimensional construct encompassing individual motivations to achieve goals within an environmental setting (Cassidy and Lynn 1989; Ward 1997). McClelland (1961) first hypothesized that high nAch predisposes individuals toward an entrepreneurial orientation, as those individuals obtain a higher degree of achievement satisfaction from entrepreneurial activities. The construct of nAch relates to various elements of the Big Five and does so to a different extent depending on whether intrinsic or extrinsic nAch is being examined (Hart et al. 2007).

3.2.2 Integrated insights from our review

Few of the previous studies on nAch actively differentiated between different types of entrepreneurs. Consequently, the reviews that exist on the topic can only differentiate between very few categories of entrepreneur sub-types, for example between entrepreneurs with either growth- or income-orientation. A meta-analysis by Stewart and Roth (2007) argued that inconsistencies in the findings of previous studies on nAch were likely due to different entrepreneur samples. While some studies found entrepreneurs to have higher nAch than managers (Begley and Boyd 1987), others observed no difference (Cromie and Johns 1983). Stewart and Roth (2007) claimed that these outcome differences likely stemmed from variation in the definitions of the term “entrepreneur” and in the entrepreneur samples. They concluded that (1) entrepreneurs in general had moderately higher nAch than managers; (2) entrepreneurs who founded a business rather than inheriting one had higher nAch; and (3) entrepreneurs with a growth-orientation had higher nAch than those who were income-oriented. This is in line with Stewart et al. (1999), who compared corporate managers and entrepreneurs who were differentiated as growth-oriented and strategically planning or as interested in providing family income. The growth-oriented entrepreneurs had significantly higher nAch than the corporate managers and family income-oriented entrepreneurs. Interestingly, the family income-oriented entrepreneurs were more similar to the corporate managers than to the growth-oriented entrepreneurs.

However, it should be noted that all but one of the studies in the Stewart and Roth (2007) review date back to 1999 or earlier. Entrepreneur types and business orientations are likely to have changed since then, especially given the creation of entirely new sectors and business models. Furthermore, while they noted some differences between entrepreneur groups across the studies (e.g., owners or founders), other differences were not investigated despite some of the reviewed studies making more detailed differentiations between entrepreneur types. For example, some of the reviewed studies specifically investigated nAch in small, early-stage companies (Utsch et al. 1999) or companies in the manufacturing or service industry (Bellu et al. 1990). Despite this, neither the stage nor the industry of the companies was differentiated. Nevertheless, Stewart and Roth (2007) demonstrated the benefit of distinguishing between entrepreneur types, as nAch differences can be observed. Evidently, there is a gap in the existing literature regarding the effect of nAch on entrepreneurial performance.

Second, some of the studies on nAch investigated the personality traits of non-entrepreneurs, by examining entrepreneurial intention in individuals who had not yet founded a business. For example, Zeffane (2013) demonstrated that nAch was the most important determinant of self-assessed entrepreneurial potential of business students in the UAE. Other studies compared these pre-founding non-entrepreneurs to individuals who were practicing entrepreneurs in the stricter sense. For example, Taormina and Lao (2007) compared the effects of nAch on Chinese respondents who were interested in starting a business, were planning to start a business, or had already established a business. The respondents who had already started a business had higher nAch than those who were planning to do so, who themselves had higher nAch than the respondents who were not interested in starting a business. These findings show that there are significant nAch differences between individuals who are practicing entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneur individuals with entrepreneurial interest. Because of this, caution should be taken when purely non-entrepreneurial samples with entrepreneurial interest are tested to investigate entrepreneurial personalities in general.

3.2.3 Summary: need for achievement

Stewart and Roth (2007) confirmed the benefit of differentiating entrepreneur types by observing nAch differences not only between entrepreneurs and managers but also between founding and inheriting entrepreneurs and between growth-oriented and income-oriented entrepreneurs. However, the research has yet to thoroughly differentiate entrepreneur types. Overall, there have been few studies on nAch to date that systematically differentiate between entrepreneur sub-types, for example, regarding growth- or income-orientation. Future research with systematic differentiation of additional sub-types would likely find that nAch varies by orientation or business type. For example, entrepreneurs with high nAch may be more willing to take Risks and prefer a growth-oriented setting, while those with low nAch may prefer a safe but steady environment. Furthermore, the limited research on entrepreneur sub-types currently focuses on niche groups. This trend makes it difficult to draw general inferences about entrepreneurs. Future studies on nAch should clearly differentiate the entrepreneur sub-types in their samples.

3.3 Innovativeness

3.3.1 Preface: concept introduction

Entrepreneurial Innovativeness is one of the first psychological traits to have received academic attention. An early hypothesis posited that entrepreneurs and managers would differ most in terms of their inclination toward innovation (Schumpeter 1934). Accordingly, Innovativeness is a personality trait that is often a central component of entrepreneurial orientation (Kraus et al. 2019) and activity (Mueller and Thomas 2001). While definitions of Innovativeness vary across the academic literature (Hurt et al. 1977), we adopt the following definition: “interindividual differences in how people react to […] new things” (Goldsmith and Foxall 2003). While Innovativeness at the individual and company levels is linked (Strobl et al. 2018), in this review, we investigated Innovativeness exclusively at the individual level rather than at the team or company level.

Innovativeness can be measured either temporally, i.e., how quickly an individual adopts innovations, or operationally, i.e., how frequently an individual chooses innovative behavior (Midgley and Dowling 1978). There are multiple measures of Innovativeness as a personality trait, none of which are consistently applied in academic research. Examples include the Adaption-Innovation Inventory (Kirton 1976) and the Jackson Personality Inventory (Jackson 1994). Alternatively, Innovativeness can be measured as a behavioral outcome through, for example, the Innovative Behavior Inventory (Lukes et al. 2009; Lukes and Stephan 2017).

3.3.2 Integrated insights from our review

As Kerr et al. (2018) poignantly noted, “the biographies of Steve Jobs alone likely outnumber the formal academic studies” on entrepreneurial Innovativeness. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no published meta-analysis or literature review has exclusively focused on the relationship between Innovativeness and entrepreneurial interests or activities. The reviews that have analyzed Innovation and entrepreneurs (Brem 2011; Schmitz et al. 2017) have mainly done so in terms of innovative outcomes, innovative processes or organization-wide Innovation. Innovativeness as an entrepreneurial personality trait, however, can occasionally be found as a sub-topic within general meta-analyses or literature reviews. For example, as part of their meta-analysis, Rauch and Frese (2007) investigated the predictive validity of Innovativeness, among other personality traits, on entrepreneurial activity and success. The studies they included defined entrepreneurs as active or interested independent business owners or active managers. Innovativeness was significantly and positively correlated with business creation and business success. However, there were no further entrepreneur-type differentiations in the individual studies.

Our literature review of empirical studies observed a general link between Innovativeness and entrepreneurial interest (Altinay et al. 2012) and venture performance or survival (Hyytinen et al. 2015), with a negative association in the latter. However, few studies have performed any kind of entrepreneur-type differentiation. One positive example is Lukes (2013), who investigated differences in innovative behavior between entrepreneurs and managers through samples drawn from Germany, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Switzerland. Lukes (2013) measured innovative behavior with the Innovative Behavior Inventory (Lukes et al. 2009) in computer-assisted telephone interviews. The study differentiated between (1) entrepreneurs with employees, (2) self-employed individuals without employees, (3) employed managers, and (4) regular employees. Unlike most other studies, it excluded students, unemployed people, homemakers, and pensioners from the sample. It found that the entrepreneurs with employees displayed the most innovative behavior. The employees without subordinates displayed the least innovative behavior except on a subscale of “involving others”, where self-employed individuals displayed the least innovative behavior. The entrepreneurs and the self-employed individuals generated new ideas more often than the managers, who had new ideas more often than the employees. The employees searched for new ideas less often than the entrepreneurs, self-employed individuals, and managers. The entrepreneurs were the most active in terms of implementing novel ideas. Interestingly, no differences were found between the entrepreneurs across the four countries from which the sample was taken.

3.3.3 Summary: innovativeness

Despite entrepreneurial Innovativeness receiving early academic attention, it remains largely uninvestigated. In our review, we did not identify a single published meta-analysis or review dedicated solely to entrepreneurial Innovativeness. Few individual studies on this topic actively differentiated entrepreneur sub-types. Those that did (e.g. Lukes 2013), however, consequently identified personality differences between the sub-types. While the number of studies differentiating Innovativeness between entrepreneur sub-types is insufficient to draw any conclusions, these initial observations encourage further differentiation in future research.

3.4 Entrepreneurial self-efficacy

3.4.1 Preface: concept introduction

Self-Efficacy is a person’s perception of or belief in their “ability to influence events that affect their lives” (Bandura 2010). It can change over the course of a lifetime, for example, through dedicated interventions (Bachmann et al. 2020). Self-Efficacy is most commonly measured through a 22-item multidimensional measure (Chen et al. 1998). Several other measures of Self-Efficacy have been developed with a varying number of subdimensions (Lee and Bobko 1994; Mone 1994; Maurer and Pierce 1998; Chen et al. 2001). The breadth of measures alone suggests the potential for inconsistency across studies in the way in which Self-Efficacy is defined and measured (McGee et al. 2009; Drnovsek et al. 2010).

Self-Efficacy is widely agreed to be domain-specific (Schjoedt and Craig 2017) and to therefore vary depending on the context. Domain-specificity means that Self-Efficacy is a multidimensional construct that varies depending on the situation or context. For example, individuals can have high beliefs about their performance on a history test while having low beliefs about their ability on a biology test (Zimmerman 2000). Thus, Self-Efficacy can be higher in one domain and simultaneously lower in another. For this reason, narrowing the investigation specifically to Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE), which is domain-specific to the entrepreneurial context, is necessary. ESE encompasses an individual’s self-perceived ability regarding entrepreneurial outcomes (Chen et al. 1998; Newman et al. 2019). Using a general Self-Efficacy measure instead of a specific entrepreneurial measure may reverse the direction of the findings (Hyun et al. 2019).

3.4.2 Integrated insights from our review

In our literature review, we again identified the two previously mentioned themes: previous research used largely different entrepreneurial sub-types when investigating ESE, and prior studies often relied on non-entrepreneur samples, such as students, when investigating ESE as an entrepreneurial personality trait.

First, regarding the use of different entrepreneur sub-types, a literature review by Newman et al. (2019) reported mixed results, with some studies showing a link between ESE and venture creation (Hechavarria et al. 2012; Hopp and Stephan 2012) and others not (Kolvereid and Isaksen 2006; Dalborg et al. 2015). Without being able to infer causality, a potential explanation for the mixed results may be that the examined studies used different definitions of the term “entrepreneur” and thus employed different sample types. We positively noted that Newman et al. (2019) differentiated between some of the entrepreneur types in the samples in the studies they examined. For example, regarding entrepreneurial intentions, they separated studies with samples of students from those with samples of working people. However, the differentiation could have extended further, for example toward growth- and income-oriented entrepreneurs, which some of the analyzed studies investigate (Douglas 2013). Additionally, some of the studies relied on relatively narrow subsets of entrepreneurs, such as US homebrewers (Biraglia and Kadile 2017) or academics (Prodan and Drnovsek 2010), which can be differentiated from entrepreneurs in general.

Second, we again noted the widespread use of non-entrepreneur samples, such as students, in the previous literature. For example, the studies that compared entrepreneurs to non-entrepreneurs typically included only students in their samples (Culbertson et al. 2011). However, we noted that aside from individual studies (e.g. Chen et al. 1998), there appeared to be a lack of research on between-group comparisons, for example, between entrepreneurs and managers.

Regarding within-group studies, in our present literature review, we noted largely positive effects of ESE on entrepreneurial intention (Chen et al. 1998; Wilson et al. 2007; Laguna 2013) and firm performance (Luthans and Ibrayeva 2006). In most of the studies we reviewed, entrepreneurial intention was the dependent variable. Moreover, the most frequently tested sample was again university students. Arguably, as noted previously, students are not actual entrepreneurs despite frequently being used as entrepreneurial proxies in the previous literature. The choice of this sample may suffice to explain why most of these studies examined entrepreneurial intentions: students will not yet have started a business, so their venture creation and entrepreneurial success are not yet measurable. Importantly, the validity of students as proxies for entrepreneurs is debatable. Some scholars believe there are drawbacks to using students as entrepreneurial proxies (McGee et al. 2009), while others call for differentiating between different types of students if sampling students is necessary (Chen et al. 1998; Hemmasi and Hoelscher 2005).

Due to the widespread use of student samples and the lack of differentiation between different entrepreneur types, it is difficult to draw conclusions about ESE in different types of entrepreneurs. Future research must more clearly differentiate between, for example, growth-oriented and income-oriented entrepreneurs. Since Self-Efficacy is related to factors such as Risk-taking (Llewellyn et al. 2008), high levels of ESE would likely be found in growth-oriented start-up entrepreneurs and not income-oriented family-business owners.

3.4.3 Summary: entrepreneurial self-efficacy

The previous reviews largely focused on the effect of ESE on entrepreneurial outcomes; thus, ESE differences across entrepreneur types have yet to be systemically analyzed. Most of the studies examined in this review focused on entrepreneurial intention as a dependent variable, largely because their samples consisted primarily of university students. The lack of diverse entrepreneurial samples currently limits the conclusions we can draw about individual entrepreneurial sub-types and allows few inferences toward entrepreneurs in general.

3.5 Locus of control

3.5.1 Preface: concept introduction

Locus of Control (LOC) is a construct that describes the extent to which individuals attribute outcomes to internal factors, such as effort and talent, or external factors, such as luck (Rotter 1966). LOC can be measured with a range of scales, including single-continuous-dimension scales (“Internalism–Externalism Scale”; Rotter 1966), bidimensional measures (Suárez-Álvarez et al. 2016), or multidimensional measures (Levenson 1973; Wallston et al. 1978; Lachman 1986). LOC appears to change over the course of a lifetime (Jennings and Zeithaml 1983). Should LOC have an impact on entrepreneurial activity and success, the ability to alter it would have interesting implications in several respects, such as entrepreneurial education.

3.5.2 Integrated insights from our review

There have been several literature reviews on topics related to LOC, such as general LOC reviews (Lefcourt 1972; Reid 1985), reviews on LOC and organizational change (Kormanik and Rocco 2009), and reviews on LOC and health (Strudler Wallston and Wallston 1978). However, to our knowledge, there has been just one literature review dedicated solely to LOC and entrepreneurship (Jennings and Zeithaml 1983), which dates back nearly four decades. The authors reviewed studies from 1971 to 1979 on LOC in organizational and managerial settings and extrapolated their findings to entrepreneurship. They found that a higher internal LOC is associated with stronger entrepreneurial intention and activity (Pandey and Tewary 2011) and higher rates of entrepreneurial success (Hornaday and Aboud 1971; Andrisani and Nestel 1976; Anderson 1977). However, only one of the studies reviewed by Jennings and Zeithaml (1983) differentiated between entrepreneur types: an unpublished doctoral thesis by Scanlan (1979) separated growth-oriented entrepreneurs from income-oriented entrepreneurs. Here, no significant differences regarding LOC were found between the two types.

One potential drawback of the review by Jennings and Zeithaml (1983) is that all of the reported studies used the Rotter (1966) Internalism–Externalism Scale for measurement. This scale may be a problematic measure for entrepreneurship research, as it includes several dimensions that lie outside the realm of entrepreneurship, such as “political responsiveness”. Therefore, the dimensions obtained using the scale may not be valid or useful predictors of entrepreneurial outcomes. Due to the various problems with the Rotter (1966) scale (Marsh and Richards 1986), multidimensional LOC measures may be more beneficial for future entrepreneurial LOC research.

In our present review, we observed that most of the studies on LOC did not differentiate between entrepreneur types. The few positive examples performing differentiations include Kerr et al. (2019), who compared entrepreneurs who self-identified as founders of their companies to both non-founding CEOs or owners and other types of employees. The founding entrepreneurs displayed the highest internal LOC, followed by the non-founding CEOs or owners, who themselves showed higher internal LOC than the employees.

Other studies involved a narrow sub-set of entrepreneurs. For example, Ahmed (1985) conducted a study on Bangladeshi entrepreneurs who had immigrated to the UK by comparing them with non-entrepreneurs; they similarly found that the entrepreneurs were higher in internal LOC than the non-entrepreneurs. Overall, the studies comparing different groups, such as entrepreneurs and managers, generally found that the entrepreneurs had higher internal LOC but did not conclusively differentiate between entrepreneur types.

The studies on within-group effects were mainly limited to student samples and thus typically examined the effects of LOC on entrepreneurial intention. Most of these studies found that higher internal LOC relates to stronger entrepreneurial intention. While the studies on practicing entrepreneurs were limited, the student samples spanned a variety of definitions and geographical locations. Examples of student samples used as entrepreneurial proxies included British hospitality students (Altinay et al. 2012), Iranian public university students (Karimi et al. 2017), or Romanian engineering and economics students (Voda and Florea 2019). Despite the breadth in samples of students with entrepreneurial interest, the studies typically found that internal LOC positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

The studies that went beyond student samples investigated venture creation, work satisfaction, and firm performance or growth. The usual link between LOC and entrepreneurial intention was found less often in the later stages of firm existence. For example, Caliendo and Kritikos (2008) found no effect of LOC on venture size in a sample of German business incubator participants. Similarly, in a sample of entrepreneurs belonging to firms with an age of at least three years and at least five employees, Imran et al. (2019) observed no direct link between internal LOC and firm performance. However, the effect of LOC on firm performance became positive and significant when mediated by entrepreneurial orientation. In different settings, LOC had a direct link with firm performance. For example, Lee and Tsang (2001) found that internal LOC had a positive impact on venture growth in a sample of Chinese entrepreneurs running SMEs in Singapore.

3.5.3 Summary: locus of control

To our knowledge, there has only been one literature review (Jennings and Zeithaml 1983) dedicated solely to entrepreneurial LOC. This review observed that higher internal LOC was associated with stronger entrepreneurial intention, higher degrees of entrepreneurial activity, and higher rates of entrepreneurial success. Our review confirmed the link between LOC and entrepreneurial intention. However, to our knowledge, most of the studies to date lacked a systematic differentiation between entrepreneur sub-types. Further, as with those on other personality traits, studies frequently limited their samples to students and thereby were inherently restricted to examining entrepreneurial intention.

Despite variation in the samples used when testing entrepreneurial intentions in students, previous studies have observed a positive relationship between internal LOC and entrepreneurial intentions. Regarding venture growth and performance, studies using heterogeneous samples of different types of entrepreneurs partially revealed mixed results. We cannot infer causality at this point, but a potential explanation may be that the outcome differences were due to definitional variation. Should future research systematically investigate LOC differences across entrepreneur types, it is likely that successful entrepreneurs will score higher on internal LOC, as external LOC is associated with a lesser ability to cope with challenges, better performance in stressful situations, greater innovation, and less Risk aversion (Jennings and Zeithaml 1983).

3.6 Risk attitudes

3.6.1 Preface: concept introduction

Risk attitudes describe individual decision-making preferences under uncertainty (Eeckhoudt and Schlesinger 2013). While Risk averse individuals prefer outcomes that are certain, Risk prone people prefer outcomes with higher levels of uncertainty. Risk attitudes are related to other personality traits, such as nAch (Meyer et al. 1961) and Self-Efficacy (Krueger and Dickson 1994). Most entrepreneurial studies have focused on Risk-taking propensity, which can be defined as an individual orientation toward taking Risks (Antoncic et al. 2018). Risk-taking propensity can change over the course of an individual’s life, typically decreasing with age (Josef et al. 2016; Mata et al. 2016) and in response to exogenous or emotional shocks (Schildberg-Hörisch 2018).

3.6.2 Integrated insights from our review

The earliest investigation into entrepreneurial Risk as a personality trait (Knight 1921) established a model of competition and uncertainty. Knight (1921) hypothesized that entrepreneurs would be more inclined to take opportunities despite potential risks. Successful entrepreneurs would be those entrepreneurs with the most balanced Risk judgments. More recent research has confirmed many of these initial judgments. This widespread research into entrepreneurial Risk-taking propensity, however, typically has not sufficiently distinguished between different types of entrepreneurs.

Such differentiation between different sub-types of entrepreneurs is, however, important because there have been inconsistencies in the findings of previous studies. For example, in the comprehensive review by Kerr et al. (2018), some of the studies found no link between Risk propensity and performance (Zhao et al. 2010), some observed that higher Risk propensity related to lower performance (Hvide and Panos 2014), and some revealed that higher Risk propensity related to higher performance (Cucculelli and Ermini 2013). Interestingly, the entrepreneur samples in these studies were quite diverse. Zhao et al. (2010) based their findings on the following definition of entrepreneurs: individuals who are founders, owners, and managers of small businesses. The sample in the study conducted by Cucculelli and Ermini (2013) was drawn from 178 Italian manufacturing companies, and the entrepreneurs were defined as those individuals “in charge of major company decisions”. Hvide and Panos (2014) tested a sample of common stock investors in terms of their sales and returns on assets in ventures they had founded. Using stock market participation as a high Risk-taking proxy, they compared this group of “entrepreneurs” to other entrepreneurs without stock market experience. These studies are merely exemplary but demonstrate that there is significant definitional variation.

Nevertheless, we made a positive observation that some studies did differentiate further between entrepreneur sub-types, primarily in terms of growth or income orientation. Growth- and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs typically exceeded income- and necessity-oriented entrepreneurs in terms of Risk-taking propensity. For example, in a meta-analysis investigating differences in Risk-taking propensity between entrepreneurs and managers, Stewart and Roth (2001) differentiated between growth-oriented and income-oriented entrepreneurs. There was a larger difference between the Risk-taking propensity of the managers and the growth-oriented entrepreneurs than between the risk-taking propensity of the managers and the family-income-oriented entrepreneurs. Thus, it appears that growth-oriented entrepreneurs are more inclined toward Risks than are income-oriented entrepreneurs. A further positive example is a study by Block et al. (2015), who differentiated between German early-stage, necessity-driven entrepreneurs and German early-stage, opportunity-driven entrepreneurs in an online survey. The entrepreneurs were assigned to sub-groups based on their self-classification of whether they had taken advantage of new business ventures or used entrepreneurship as their only employment option. Risk-taking propensity was measured both directly through self-perception and indirectly through a lottery-type question with a hypothetical investment. The opportunity-driven entrepreneurs were more willing to take Risks than the necessity-driven entrepreneurs.

We found some studies that differentiated between entrepreneur types while investigating the effects of Risk attitudes on venture creation. For example, Antoncic et al. (2018) examined the effect of Risk-taking propensity on entrepreneurial activity. Questionnaires were administered to 1414 university students across six countries. The students were classified as non-entrepreneurs (24.4%), maybe-entrepreneurs (52.6%), potential entrepreneurs (15.9%), and practicing entrepreneurs (7.1%). Across these groups, Risk-taking propensity was again associated with entrepreneurial activity in an inverted-U shape. Those individuals who ranked highest in Risk-taking propensity were likely to launch a venture in the next three years but had not yet done so. The practicing entrepreneurs exceeded only those individuals who might launch a venture at some point in the distant future and those who were not interested in launching one at any point. However, by relying on a student sample with only 7.1% practicing entrepreneurs, it must be noted that this study involved primarily on non-entrepreneurs and individuals in the pre-founding phases. We would encourage future research to build on these findings through a more detailed differentiation of venture phases of already practicing entrepreneurs.

Last, we would like to mention some observations on potential problems with the existing research on entrepreneurial Risk attitudes. There appears to be no agreed-upon measure of Risk attitudes, which makes comparisons between studies difficult, and perhaps impossible. The studies often used self-reported measures, to which entrepreneurs typically respond with overconfidence (Astebro et al. 2014) and, therefore, biased judgments. The studies may not be directly comparable to those using different Risk attitude measures (Palich and Bagby 1995). These measures include behavioral and quantitative proxies, such as stock market participation rates and R&D expenditures. Furthermore, most of the studies tested general Risk attitudes instead of domain-specific entrepreneurial Risk-attitudes. These broad attitudes likely capture elements that are unrelated to entrepreneurial activity.

3.6.3 Summary: risk attitudes

In our review we took note of the mixed results regarding the relationship between Risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurial success. Studies have concluded that Risk-taking is negatively (Hvide and Panos 2014), positively (Cucculelli and Ermini 2013), or not related to entrepreneurial performance (Zhao et al. 2010). We demonstrated that different definitions of the term “entrepreneur” were used across these studies. Thus, disparate entrepreneurial samples were used.

There are several potential explanations for these inconsistent findings. First, the inconsistencies may be due to the lack of an agreed-upon Risk attitude measure. While some studies used self-reported measures, others used behavioral or indirect measures of Risk attitudes. Second, the inconsistencies may be due to definitional variation. Few of the studies on Risk-taking differentiated between entrepreneur sub-types even though there are likely substantial differences between these sub-types in terms of Risk attitudes. For example, the level of Risk-taking propensity of opportunity-driven entrepreneurs exceeds that of necessity-driven entrepreneurs (Block et al. 2015), and students in the planning phase of a future entrepreneurial venture exceed already practicing entrepreneurs in terms of their level of Risk-taking propensity (Antoncic et al. 2018). Future research should employ methodological designs that allow for direct and simultaneous comparisons between a variety of entrepreneur sub-types in terms of Risk-taking propensity.

4 Integrated insights per entrepreneur sub-type

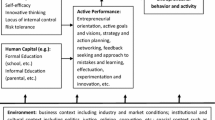

In the next part, we pivot our approach from the perspective of personality traits to the perspective of entrepreneur sub-types. As part of our literature review, we classified each paper in terms of the entrepreneur sample used. The list of potential entrepreneur sub-types is infinite, and this is one of the potential problems in defining the traits of an entrepreneur. Nevertheless, in Fig. 2, we present all entrepreneur sub-types that emerged from the papers included in the sample in our literature review and classify them according to the six outlined personality traits. Then, we offer some insights into six selected entrepreneur sub-types.

Entrepreneur sub-types from literature review. *Incubator participants arguably can be counted to non-entrepreneurs if in pre-founding stage. Notes: Percentages add up to more than 100% because some studies examined more than one entrepreneurial sub-type; High risk-attitude means more risk-prone or less risk-averse; “General ‘entrepreneurs’” include general self-employed or general SME owners; Selected references for Fig. 2: Big Five (Roberts 1989; Schmitt-Rodermund 2004; Caliendo et al. 2014; Espíritu-Olmos and Sastre-Castillo 2015; Staniewski et al. 2016; Mei et al. 2017; Liang 2019; Yang and Ai 2019; López-Núñez et al. 2020), nAch (Ahmed 1985; Roberts 1989; Stewart et al. 1999; Lee and Tsang 2001; Hansemark 2003; Taormina and Lao 2007; Caliendo and Kritikos 2008; Altinay et al. 2012; Staniewski et al. 2016; Imran et al. 2019), Innovativeness (Stewart et al. 1999; Altinay et al. 2012; Lukes 2013; Hyytinen et al. 2015; Staniewski et al. 2016), ESE (Luthans and Ibrayeva 2006; Hmieleski and Corbett 2008; BarNir et al. 2011; Hopp and Stephan 2012; Cumberland et al. 2015; Staniewski et al. 2016; Schmitt et al. 2018; Boudreaux et al. 2019), Internal LOC (Lee and Tsang 2001; Hansemark 2003; Owens et al. 2013; Caliendo et al. 2014; Espíritu-Olmos and Sastre-Castillo 2015; Staniewski et al. 2016; Karimi et al. 2017; Kerr et al. 2019; Voda and Florea 2019), Risk attitudes (Cramer et al. 2002; Macko and Tyszka 2009; Masclet et al. 2009; Caliendo et al. 2010, 2014; Brown et al. 2011; Kreiser et al. 2013; Niess and Biemann 2014; Skriabikova et al. 2014; Kerr et al. 2019)

4.1 Characteristics of selected entrepreneur sub-types

For the following analysis, we selected six exemplary entrepreneur sub-types in the academic literature to date. An explanation of these sub-types can help to elucidate how definitional variations relate to differences in the personality profiles.

The entrepreneurial archetype While little attention has been given to differentiating entrepreneur sub-types, many studies have investigated what personality defines entrepreneurs in general. Despite various sub-types likely differing, the combination of several sub-types has frequently been tested when investigating entrepreneurs. These studies including samples of general entrepreneurs have largely revealed a pattern of E+ , C+ , O+ , N−, and A− for the Big Five (Schmitt-Rodermund 2004; Antoncic et al. 2015); high nAch (Stewart et al. 1999; Imran et al. 2019); high ESE (Imran et al. 2019; Kerr et al. 2019); high internal LOC (Kerr et al. 2019); and, typically, a U-shaped risk-propensity relationship (Antoncic et al. 2018). At the same time, various entrepreneur sub-types have frequently been extrapolated to entrepreneurs in general, and differentiations have rarely been performed. Because of this, it is important to further investigate differences in individual entrepreneur sub-types.

Nascent entrepreneurs A sub-type of entrepreneurs that has frequently been examined is nascent or early-stage entrepreneurs. Again, the precise definitions and tested samples have varied significantly between studies and even within the category of nascent entrepreneurs. Thus, some studies on nascent entrepreneurs described their subjects as having founded a business up to several years ago (Staniewski et al. 2016); others referred to nascent entrepreneurs as general, early-stage entrepreneurs (Yang et al. 2020); and others included individuals who had only partially decided to start a business or who were in the founding stages (Dalborg et al. 2015). One study we mention in the previous paragraph also included samples of entrepreneurs along the founding process (Antoncic et al. 2015). While each approach is valid, it is difficult to draw combined insights regarding a general group of nascent entrepreneurs and even less so regarding entrepreneurs in general.

Nevertheless, some insights into the personality profile of nascent entrepreneurs can be drawn. Nascent entrepreneurs appear to differ from the entrepreneurial archetype. For nascent entrepreneurs, high Innovativeness does not seem to have the same favorable effect on firm survival (Hyytinen et al. 2015). Further, regarding nAch, there appear to be differences between early-stage entrepreneurs, i.e., individuals who have founded a business, and pre-stage entrepreneurs, i.e., those individuals who are interested in starting a business (Taormina and Lao 2007). The stronger their nAch is, the more likely individuals are to progress from the pre-stage to the early-founding stage.

Family business entrepreneurs Despite the existence of comprehensive definitions of family businesses (e.g. Donnelley 1964), most of the research on family businesses has not applied a consistent definition of what constitutes a family firm (Diéguez-Soto et al. 2015). In accordance with the high prevalence of family firms in most economies (Kraus et al. 2012), there has been at least some research on this entrepreneur sub-type. Succession planning within the family is a central component of family businesses, with the main motives typically being continuity over generations and family harmony (Gilding et al. 2014). Accordingly, a family background of entrepreneurship relates to higher entrepreneurial intention (Palmer et al. 2019a, b) in future generations. In our review, we noted that this sub-type of entrepreneurs differed from the entrepreneurial archetype, particularly regarding Risk attitudes and LOC. For example, contrary to general entrepreneurs, later generations of family business entrepreneurs show lower internal LOC (Zellweger et al. 2011).

Technological/tech-industry entrepreneurs One of the first associations that may come to mind when thinking about entrepreneurs is that of high-growth technology start-ups. Nevertheless, this sub-type of entrepreneurs has not yet received widespread academic attention in terms of personality classification. Individual studies on technical entrepreneurs have indicated that differences between this sub-type and more general entrepreneurs exist. For example, Roberts (1989) showed that technical entrepreneurs are more moderate in their nAch than would be expected of general entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, this is a sub-type of entrepreneurs that requires significantly more research attention.

Agrirural entrepreneurs The group of agrirural or farming entrepreneurs is a group that has received some attention in terms of empirical investigations. Further, we observed that the results related to this subgroup of entrepreneurs were frequently extrapolated to entrepreneurs in general, often without a clear description of the agrirural sample in the title or abstract (Sohn 2017). This was the case despite agrirural entrepreneurs differing from general entrepreneurs in several ways. For example, while there is a relationship between Conscientiousness and entrepreneurial activity for general entrepreneurs (Antoncic et al. 2015), agrirural entrepreneurs’ alertness is only partially affected through higher Conscientiousness (Liang 2019). Yang and Ai (2019) further demonstrated that agrirural entrepreneurs differ from self-employed non-agrirural, self-employed entrepreneurs in the Big Five dimensions. We encourage all future studies with agrirural entrepreneurs as their sample to clearly state that this sub-type is being tested.

Students with entrepreneurial interest As outlined previously, students have frequently been relied upon in empirical papers that attempt to characterize actual entrepreneurs. The number of studies that have done so is surprisingly high—in our initial, prefiltered sample of studies, approximately 30% used some form of student sample. However, it is highly questionable whether students can be part of the entrepreneur sub-type at all, as they mostly have not yet founded a venture. Despite students not having founded a business yet, students with entrepreneurial interest have frequently been used as samples when investigating the entrepreneurial personality. These studies are inherently limited to investigations on entrepreneurial intention rather than activity because the students in the samples will not yet have founded a business.

Nevertheless, due to their frequent use as entrepreneurial proxies, it is worth considering in what ways these students with entrepreneurial interest are similar to or different from actual entrepreneurs. In some ways, entrepreneurially oriented students share personality dimensions with practicing entrepreneurs. For example, entrepreneurially interested students have high levels of Extraversion and Risk-propensity (Espíritu-Olmos and Sastre-Castillo 2015), as well as high ESE (Chen et al. 1998). Simultaneously, entrepreneurially interested students differ from practicing entrepreneurs in several important personality dimensions. For example, Openness to Experience (Mei et al. 2017) and Neuroticism (Espíritu-Olmos and Sastre-Castillo 2015) appear to have marginal effect on entrepreneurial intention for students. Despite these indications our review can offer, we cannot draw direct conclusions on the validity of using student proxies for entrepreneur samples until direct comparisons are performed between both types of samples in future empirical studies.

4.2 Integrated insights from entrepreneur sub-types

Across the different personality traits and entrepreneur sub-types we deduced five major observations from our literature review. First, we noted that the general category of “entrepreneur” has received significant academic interest but without further differentiation of any entrepreneur sub-types despite substantial differences between these groups. Thus, we observed a vast number of disjointed studies specific to entrepreneur sub-types, industries, or business types.

Second, those few entrepreneur sub-types that have been researched show different personality profiles. Thus, there appears to not be a general “entrepreneur” profile that fits all sub-types. Instead, there are significant differences between the individual types. This should encourage future research to perform further differentiations between entrepreneur sub-types.

Third, the extent to which individual personality traits have received attention in academic literature varies. While Risk attitudes and the Big Five have received significant academic attention, other traits that may be even more central to the entrepreneur personality profile require further empirical support. For example, Innovativeness may be a core factor differentiating entrepreneurs from non-entrepreneurs. Despite this, the empirical investigations are limited and to our knowledge, no literature review focusing solely on entrepreneurial Innovativeness as a personality trait exists.

Fourth, the personality traits differ in terms of their results. While there are some personality traits that show consistent findings independent of entrepreneur sub-type, others show more diverse results depending on the entrepreneur sub-type examined. For example, ESE was generally high for general entrepreneurs and for all entrepreneur sub-types analyzed in our review. In contrast, Risk attitudes showed more diverse results.

Our last main observation is that approximately 30% of the studies in our literature review sample tested students despite claiming to investigate entrepreneur personalities. Students with or without entrepreneurial interest are frequently used as proxies in the entrepreneurship literature, perhaps because of their easy accessibility. However, drawing inferences from their traits toward entrepreneur characteristics in general may be difficult, as they are not actual entrepreneurs.

5 Discussion

5.1 Summary and contributions

This literature review used a systematic literature review methodology (Tranfield et al. 2003) to analyze differences in personality traits across various entrepreneur sub-types. Our literature review examined entrepreneur sub-types and the extent of the differentiation performed in previous papers across six personality traits.Footnote 4 We were led by three main research objectives, which we investigated throughout our review.

First, we explored whether the previous research on entrepreneurial personality varied in its definitions in the way we had assumed. Here, we noted that previous research had extreme variation in the definition of the term “entrepreneur”. In fact, some studies did not provide an explicit definition in their sample description. The literature reviews and meta-analyses in our review also rarely made explicit distinctions between entrepreneur sub-types, meaning they compared studies that used vastly different samples.

Second, we examined whether there were inconsistent findings in the previous research. Without being able to infer causality from a literature review, one potential explanation for such inconsistencies is the use of different definitions. Indeed, we observed that the findings differed strongly between various studies. In most of these cases of inconsistencies, different entrepreneurial samples had been used. We explicitly noted that causality cannot be inferred from such observations alone. Third, we outlined the personality differences between entrepreneur sub-types in the few studies that differentiated between them. When studies differentiated between entrepreneur sub-types, there were typically observable personality differences between the sub-types.

Based on these observations, we make two main contributions to research on entrepreneurial personality traits. First, through our literature review, we demonstrate the importance of being specific in samples and definitions. Previous research has used widely different definitions of entrepreneurs, consequently testing discrepant samples, and revealing somewhat inconsistent results. While we cannot infer causality from this alone, the possibility exists that these inconsistencies are due to definitional variations, which we highly encourage future research to investigate. We acknowledge that several other explanations could account for these inconsistencies, such as a lack of agreed-upon personality trait measures. We encourage future research to employ methodological designs that allow for direct and simultaneous comparisons between a variety of entrepreneur sub-types across personality traits. This would enable us to differentiate between entrepreneur types in terms of personality more clearly. In addition, our literature review shows that research must aim to precisely define the samples tested. Future literature reviews and meta-analyses should further differentiate between the different samples used in the studies they analyze, as combining the results of studies with vastly different entrepreneurial samples may lead to inaccurate findings.

Second, our literature review shows that it may be misleading to test samples consisting of non-entrepreneurs with entrepreneurial interest when aiming to investigate entrepreneurial personalities in general. At best, testing non-entrepreneurs, such as students with entrepreneurial interest, can shed light on the personalities behind entrepreneurial intentions, but such testing cannot give insights per se about individuals who have already founded a business. Thus, we further highlight the importance of being specific in defining samples and encourage the clear labeling of non-entrepreneur samples in future research.

The question arises of what follows from these initial observations. While we explicitly do not encourage every review or study to apply the same definition of entrepreneur, we strongly emphasize the need to make the definition used explicit and for future reviews to continue to systematically analyze the different samples used in individual studies. If possible, future research should rely more strongly on practicing entrepreneurs as samples when investigating the nature of the entrepreneurial personality.

5.2 Limitations of this study

This literature review assessed previous reviews and empirical studies on entrepreneurial personalities to investigate whether discrepancies in their findings could be explained by variations in the definition of the term “entrepreneur.” While this study sheds light on a more differentiated view of entrepreneurial personality, it does not enable us to make causal inferences. Further, inferences cannot be made as to whether specific traits predict entrepreneurial behavior or whether specific traits emerge because of entrepreneurial activity.

Beyond this, we recognize that the nature of the studies included in our sample may constitute a limitation. The studies on entrepreneurial personality to date have generally involved small sample sizes and have been heavily reliant on questionnaires. These questionnaires are self-report measures, where participants are free to give their own judgments but are also free to—consciously or unconsciously—deviate from their actual views and behaviors. Participants may be inclined to present a more positive view of themselves in a questionnaire, although such social desirability biases are not observed as frequently as one might expect (Conway and Lance 2010). To validate outcomes from self-report measures, behavioral tests can be used by measuring observable behavior, which is not as biased by participant adjustments. This is particularly relevant in the field of personality research, where individuals may want to portray themselves as favorably as possible. To counteract this, fake-proof measures have been developed for various personality traits, such as the Big Five (Hirsh and Peterson 2008). Other indirect methods, such as behavioral tests using reaction times or semi-structured interviews or the use of statistical rectifications (Podsakoff et al. 2003), may provide more reliable information on individuals’ personalities.

Relatedly, while this literature review focused on the lack of differentiation between entrepreneur sub-types in previous research, it must be made clear that the observed discrepancies may also stem from alternative reasons. For example, the discrepancies could be due to the inconsistent use of personality-assessment measures. For example, there are more than 20 different instruments that can be used to take nAch measurements of entrepreneurs (Stewart and Roth 2007), including both projective and objective measurements. Another reason could be that cultural differences among the multitude of countries in the sampled studies play a larger role than we considered in this review.

Finally, throughout this literature review, we investigated whether there were any differences between entrepreneur sub-types. While we were often able to report such differences and their statistical direction, we were largely unable to draw conclusions about the scale of these differences. For this, further empirical investigations are necessary.

5.3 Future research

First, in line with the main thesis of this review, we encourage future studies to define the term “entrepreneur” and describe, in detail, their entrepreneur samples more explicitly. As such, we view this as a factor of methodological correctness. This would not only make the results of individual studies more comparable but also allow for systematic differentiation between various entrepreneur sub-types. Since these sub-types are often unalike, such differentiation would likely allow for observations of discrete personality traits depending on entrepreneur type. This would advance our academic understanding of what traits define entrepreneurs and would have a variety of practical implications, such as for tailored entrepreneurial education programs.

Second, personalities are not limited to the six traits discussed in this review. There are a multitude of potential personality traits that could be investigated in research on entrepreneurs. Limiting research to a specific subset of personality traits may lead to important findings being missed. For example, this review may have focused too strongly on the positive aspects of entrepreneurial personalities. Increasingly, research is beginning to emphasize the potential “downsides” of entrepreneurial personalities (Miller 2015, 2016; Klotz and Neubaum 2016). Systematic investigations into the differences between entrepreneur sub-types in personality traits beyond those explored in this review would further develop our understanding of entrepreneurial personalities.

Third, it is likely insufficient to study personality traits as stand-alone constructs. Instead, personality traits must always be viewed within personal and environmental contexts, which requires the involvement of other factors, such as an individual’s attitude, self-identity, culture, and social environment. Further, when regarding later stages of entrepreneurial ventures and their performance, factors attributed to the ventures on a firm-level interact with individual personality traits (Palmer et al. 2019a, b). While experimental designs are naturally limited to a set of variables, future research should consider some of these additional factors when investigating entrepreneur personality traits.

Fourth, we encourage future research to branch out to novel research methodologies and designs. As already discussed, previous studies in this field have largely relied on self-report questionnaires, which may not be the most reliable means of gathering information, as self-reported findings are inherently biased (Donaldson and Grant-Vallone 2002). Novel techniques from other disciplines would be valuable additions to research on entrepreneurs. For example, expanding the use of neurological imaging techniques, such as fMRI scans (Ledezma-Haight et al. 2016), or examining the genetic basis of entrepreneurial personality traits using twin studies (Nicolaou et al. 2008; Shane et al. 2010; Shane and Nicolaou 2013) could offer novel insights into the field of entrepreneur personality.

Data availability

Tables of individual studies analyzed in the literature review provided to the Open Science Framework.

Notes

Few reviews, e.g., Kerr et al. (2018), include a differentiation by entrepreneurial type in their appendix.

The papers analyzed in our systematic literature review can be found on the Open Science Framework: osf.io.

The personality traits were (1) the Big Five, (2) Need for Achievement (nAch), (3) Innovativeness, (4) Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy (ESE), (5) Locus of Control (LOC), and (6) Risk attitudes.

The personality traits are (1) the Big Five, (2) Need for Achievement (nAch), (3) Innovativeness, (4) Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy (ESE), (5) Locus of Control (LOC), and (6) Risk attitudes.

References

Ahmed SU (1985) nAch, risk-taking propensity, locus of control and entrepreneurship. Personal Individ Differ 6(6):781–782

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211

Altinay L, Madanoglu M, Daniele R, Lashley C (2012) The influence of family tradition and psychological traits on entrepreneurial intention. Int J Hosp Manag 32:489–499

Anderson CR (1977) Locus of control, coping behaviors, and performance in a stress setting: a longitudinal study. J Appl Psychol 62(4):446–451

Andrisani PJ, Nestel G (1976) Internal-external control as contributor to and outcome of work experience. J Appl Psychol 61(2):156–165

Antoncic B, Bratkovic Kregar T, Singh G, DeNoble AF (2015) The big five personality-entrepreneurship relationship: evidence from Slovenia. J Small Bus Manag 53(3):819–841

Antoncic J, Antoncic B, Gantar M, Hisrich RD, Marks LJ, Bachkirov AA, Li Z, Polzin P, Borges JL, Coelho A, Kakkonen M-L (2018) Risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurship: the role of power distance. J Enterp Cult 26(01):1–26

Astebro T, Herz H, Nanda R, Weber RA (2014) Seeking the roots of entrepreneurship: insights from behavioral economics. J Econ Perspect 28(3):49–70

Bachmann AK, Maran T, Furtner M, Brem A, Welte M (2020) Improving entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the attitude towards starting a business venture. Rev Manag Sci p 1–21

Bandura A (2010) Self-Efficacy. Wiley, Hoboken

BarNir A, Watson WE, Hutchins HM (2011) Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. J Appl Soc Psychol 41(2):270–297

Begley TM, Boyd DP (1987) A comparison of entrepreneurs and managers of small business firms. J Manag 13(1):99–108

Bellu RR, Davidsson P, Goldfarb C (1990) Toward a theory of entrepreneurial behaviour; empirical evidence from Israel, Italy and Sweden. Entrep Reg Dev 2(2):195–209

Biraglia A, Kadile V (2017) The role of entrepreneurial passion and creativity in developing entrepreneurial intentions: insights from American homebrewers. J Small Bus Manag 55(1):170–188

Block J, Sandner P, Spiegel F (2015) how do risk attitudes differ within the group of entrepreneurs? The role of motivation and procedural utility. J Small Bus Manag 53(1):183–206

Bosma N, Content J, Sanders M, Stam E (2018) Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Bus Econ 51(2):483–499

Boudreaux CJ, Nikolaev BN, Klein P (2019) Socio-cognitive traits and entrepreneurship: the moderating role of economic institutions. J Bus Ventur 34(1):178–196

Brandstätter H (2011) Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: a look at five meta-analyses. Personal Individ Differ 51(3):222–230