Abstract

This study intends to deal with the environmental consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia, by providing a summary of the effects of COVID-19 on municipal solid waste (MSW). In this analysis, the data on domestic waste collection were collected from the Solid Waste Management and Public Cleaning Corporation (SWCorp) from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 to evaluate the relative changes in MSW percentage via a waste weighing method. The data consisted of the cumulative tonnage of MSW for every local authority in Peninsular Malaysia and was classified according to MCO phases; before the MCO, during the MCO, during the conditional MCO (CMCO) and during the recovery MCO (RMCO) phases. The results indicated that the enforcement of the early MCO showed a positive effect by decreasing the volume of MSW. This decrease was noted across 41 local authorities, which accounts for 87.23% of Peninsular Malaysia. However, the amount of MSW began to increase again when the MCO reached the conditional and recovery stages. From this, it can be concluded that the implementation of the MCO, in its various incarnations, has shown us that our lifestyles can have a harmful impact on our environment. While the pandemic was still spreading and limitations were still in place in Malaysia, local governments and waste management companies had to quickly alter their waste management systems and procedures. The current circumstance allows us to rethink our social and economic structures while improving environmental and social inclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2), also known as COVID-19, is an infectious disease declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 to be the cause of a global pandemic (Velavan and Meyer 2020). The virus spreads directly via close contact in human-to-human transmission, through respiratory droplets formed from coughs or sneezes and indirectly via contaminated surfaces such as plastics and stainless steel (Maleki et al. 2021 Vosoughi et al. 2021; Van Doremalen et al. 2020; Noorimotlagh et al. 2020; Kenarkoohi et al. 2020). To date, more than 300,000 COVID-19 instances have been recorded in Malaysia, and as a result of these record highs, more stringent measures such as lockdowns have been imposed. Malaysia is one of over 200 countries and territories actively struggling against the latest coronavirus.

Malaysia’s administration has implemented multitude movement restrictions aimed at flattening the curve of COVID-19 infections, including limitation of social movement, immediate isolation of positive COVID-19 patients, travel bans, closure of the national borders, closure of schools and educational institutions and the suspension of industrial and public transport operations (Karim and Haque 2020). Various forms of movement control orders depending on the infection situation have been initiated (Tang 2020). The government announced on 13 May 2020 that the MCO would expand into conditional MCO by 9 June 2020. Only industry sectors deemed as necessary were able to work during the MCO; everyone else was required to stay home and stay indoors. The aim of the Recovery Movement Control order (RMCO), from 10 June to 31 December 2020, was to restart and re-establish all economic and social sectors. All sectors of the economy are now able to open, subject to strict standard protocols and procedures for ordering. Theaters, kindergartens, religious venues, social and cultural activities can be reopened under the RMCO with the exception of nightclubs, which may not operate. The movement restrictions imposed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic are also responsible for numerous environmental impacts. Traffic and industrial emissions have been significantly reduced as a result of most industrial and commercial operations being strictly prohibited during the first period of the MCO. These environmental impacts are well known in countries such as China, Spain, Italy and the USA, but comparatively, there is little or no research of any kind in Malaysia (Zambrano-Monserrate et al. 2020; Muhammad et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2020). Additionally, very little effort has been made to build an overall picture of the pandemic’s effect on the environment in all of these countries.

In Malaysia, municipal solid waste was generated from residential, commercial, institutional, commercial and city areas. The average generation of municipal waste by Malaysian local authorities is calculated in this study using their corresponding cumulative MSW collections. The researchers are thus quantifying MSW generation by observing the pattern of MCO towards MSW generation in Peninsular Malaysia based on local authority areas. The study will provide an evidence-based consensus for future policy development in Malaysia regarding MSW generation and sustainable waste management following a pandemic.

Methods

Malaysia is located in Southeastern Asia with a range of inhabited regions stretching from the Malay Peninsula in the west to the northern part of Borneo Island in the east. The overall area of Peninsula Malaysia is 132,265 km2 in area which accounts for 40% of its total land mass. In Malaysia, solid waste management is managed by the Solid Waste Management and Public Cleaning Corporation (SWCorp) under the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, Jabatan Pengurusan Sisa Pepejal Negara (JPSPN), local authorities and private concessionaires. This study was focused only on the states and territories that are pursuant to regulations under the Solid Waste and Public Cleansing Management Act 2007 (Act 672) which has been enforced in Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, Johor, Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Kedah and Perlis as shown in Figure 1.

In this analysis, the data on domestic waste collection were collected from SWCorp on a monthly basis from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 to evaluate the relative changes of MSW percentage via a waste weighting method. Various forms of the movement control order were implemented by the Malaysian government based on the condition of infection in the country, i.e. Phase I (MCO: 18 March 2020 to 12 April 2020); Phase II (CMCO: 13 May 2020 to 9 June 2020) and Phase III (RMCO: 10 June 2020 to 31 December 2020). The data consisted of the cumulative tonnage of MSW for every local authority in Peninsular Malaysia. The data was classified based on MCO phases; before the MCO, during the MCO phase, during the CMCO phase and during the RMCO phase.

This data covered four different categories of local authorities in Peninsular Malaysia, namely, city council (n = 5), municipal council (n = 14), rural district (n = 27) and special and modified local council (n = 1). The data for forty-seven local authorities in Peninsular Malaysia were included in this study and are described in Table 1. First, the variation in the MSW was determined based on a percentage decrease in the cumulative tonnage of MSW between the different periods, i.e. before the implementation of MCO and during the MCO, during the MCO and the CMCO and during the CMCO and RMCO. This variation in the cumulative tonnage has been tabulated for understanding the varying trend in every region from before the implementation of the MCO until the RMCO.

Results and discussion

The volume of urban solid waste was significantly reduced during the first phase of the MCO. A cumulative tonnage analysis of MSW before and after the implementation of the MCO showed a significant reduction in MSW volume. MSW volume ranged from 549.76 to 118,521.87 and 552.54 to 98,844.73 tonnes respectively before and after MCO’s implementation. Kuala Lumpur had the largest reported decline in MSW amount of all the local authorities, dropping from 118,521.87 to 98,844.73 tonnes (−4.01%) followed by Melaka Bersejarah falling from 28,826.96 to 17,267.04 tonnes (−2.36%) and then Johor Bahru coming down from 52,137.85 to 44,643.93 tonnes (−1.53%). Before the MCO, Kuala Lumpur recorded the highest volume of MSW. Table 2 presents the difference in the cumulative tonnage of MSW before and during the implementation of the MCOs.

When the MCO reached the conditional and recovery stages, the volume of MSW waste began to increase again as restrictions on movement were lifted, and most economic and social activity resumed. The volume of MSW during this corresponding period of CMCO increased in comparison to before the MCO (from 417,606.26 to 475,044.97 tonnes, i.e. 13.75%). This pattern of increasing volume of MSW was noted across all local authorities in Peninsular Malaysia during the CMCO period. Kuala Lumpur recorded the highest increase in volume, rising from MCO = 98,844.73 to CMCO = 111,383.18 tonnes (3.00%), followed by Batu Pahat rising from MCO = 7647.59 tonnes to CMCO = 16,081.67 tonnes (2.02%), and Kota Tinggi rising from MCO = 5477.71 tonnes to CMCO = 13,296.53 tonnes (1.87%). In comparison to the MCO period, a continuous decrease could be seen in a few of the local authorities during CMCO, which contributed 21.89% of the total reduction of volume of MSW during CMCO period. Contrary to the results presented during the CMCO, there is a slight increase in the volume of MSW noted during RMCO. All local authorities in Peninsular Malaysia showed an increasing trend in the volume of MSW during the RMCO as compared to the CMCO, especially in the Kuala Lumpur. Johor Bahru also showed the highest increase in the volume of MSW, from 47,612.43 to 147,995.60 tonnes (i.e. 21.13%) followed by Iskandar Puteri rising from 29,016.58 to 85,871.01 tonnes (11.97%) and Melaka Bersejarah rising from 11,538.18 to 63,798.81 tonnes (11.00%).

These results indicate that the enforcement of the early MCO showed a positive effect by decreasing the volume of MSW. This decrease was noted across 41 local authorities which together account for 87.23% of Peninsular Malaysia. A significant decrease was noted in the volume of MSW during the MCO period. However, an increase was noted in the period between CMCO and RMCO, specifically in the bigger cities Furthermore, the population size was seen to be the major factor, which led to an increase in the cumulative tonnage of MSW. However, the overall pattern of the MSW in Malaysia showed a decrease during the early implementation of MCO and began to increase again when the MCO reached the conditional and recovery stages.

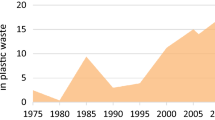

In an effort to understand the contribution of MCO on the trends of MSW, this study has produced an annual cycle of MSW, by state, in Peninsular Malaysia from year 2016 to 2020 as seen in Figure 2. The line graph is divided into two main periods, namely, before the pandemic and during the pandemic. Data examination showed that overall trends of MSW during the early period of MCO, from 8 March 2020 to 28 April 2020, show a sudden drop at the end of March to the beginning of April and indicate that the large scale of the MCO affects waste generation due to less waste being produced in public areas.

Solid waste management is an imperative to protect the environment and ensure the sustainability and quality of life for all (Shekdar 2009). It is now considered a global issue where everyone is responsible for the daily production of solid waste. Increased population, socioeconomic improvement and social changes are major factors in the increment of solid waste generation and changes in waste composition. A number of positive and negative environmental impacts have been reported as a consequence of the COVID-19 restrictions (Boroujeni et al. 2021; Caraka et al. 2020; Mahato et al. 2020). Most notably, there have been significant changes in air quality and transboundary haze emissions in the city (Sharma et al. 2020). Improvements in air quality have also been reported in other countries around the world (Jephcote et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2021). However, a dramatic rise in household plastics and medical waste was noted as a major negative environmental effect. The findings from this evaluation have an important implication on challenges and opportunities in the aftermath of the ongoing pandemic.

According to the Solid Waste and Public Waste Management Act 2007 (Act 672), solid waste is defined as any scrap material or other unwanted surplus substance or rejected products arising from the application of any process, or any substance required to be disposed of as being broken, worn out, contaminated or otherwise spoiled. The scope of solid waste in this act covers controlled solid waste, which can be divided into seven categories namely household, commercial, public, industrial, institutional and imported solid waste. In this study, a detailed assessment was done on the pattern of MSW in Peninsular Malaysia both before implementation of the MCO and during the different phases. These restrictions on human movements directly decreased the volume of domestic waste. The fall in a domestic waste generation may be due to less waste being produced in public areas. The temporary closure of most business during MCO may cause a significant reduction of waste volume in these major cities. The closure of non-essential business in these cities during MCO has significantly reduced the number of people visit physically to many of the shops (Ismail et al. 2020).

During this period, the majority of restaurants have catered to take-away food and home delivery, people have reduced working hours or work from home, as well as the cancelation of all wedding ceremonies and other meetings and gatherings. Buffets are recognized as among the main food waste contributors, so the inability of hotels and restaurants to provide buffets during the MCO has also resulted in a decline in the amount of food waste. Food waste is generated from many sources in Malaysia including, residential, industrial, institutional, commercial and urban areas (Jereme et al. 2016). This analysis indicates that the generation of municipal waste by Malaysian local authorities declined during the early MCO period due to the waste produced entering the waste stream from a single point rather than from various points. During this period, most people remain at home and prepare food for their households. There was little possibility of outside food sources during this time. The new norm of Malaysians working from home and looking at new hobbies during the stay-at-home period also may contribute to the reduction of waste. The changes in the expenditure habits of the population have therefore contributed to a significant reduction in waste during the MCO.

However, when the MCO reached the conditional and recovery stages, the volume of MSW began to increase again as restrictions on movement were lifted and most economic activities resumed. The increased waste generation caused by personal protective equipment (PPE) was followed immediately by a rise in the usage of single-use plastics (SUP). For example, demand for plastics is projected to grow by 40% in packaging and 17% in other applications, including medical usage (Prata et al. 2020). During COVID-19, safety issues around shopping in supermarkets have contributed to a preference by shoppers and providers for fresh produce wrapped in disposable containers (to prevent food contamination and prolong shelf life), as well as single-use food packaging and plastic bags to hold groceries. To resolve consumer complaints and maintain general well-being, supermarkets introduced additional health and safety initiatives such as social distancing, cleanliness, sanitation and, where possible, home delivery and/or a pick-up service. Taking advantage of these preferences, plastic industry lobbyists have addressed concerns with political officials over food quality, sanitation and cross-contamination by utilizing recycled containers and bags amid the COVID-19 pandemic. While the plastic industry has historically capitalized on these issues (Prata et al. 2020), recent concerns regarding COVID-19 protection have culminated in a reversal of policy to prohibit or limit SUP and fee payments in certain jurisdictions. Viable SARS-COV-2 virus survives longer on plastic surfaces than on other products, such as cardboard (Heidari et al. 2019; Silva et al. 2020; Noorimotlagh et al. 2021); therefore, it may be claimed that rescinding SUP bans is premature, as many users have already adjusted to utilizing non-plastic substitutes following the introduction of these policies in many jurisdictions worldwide (Xanthos and Walker 2017; da Costa et al. 2020). Furthermore, it is uncertain if reusable shopping bags could lead to a higher risk as opposed to clothing or shoes, a possible risk that could also be mitigated with better hand hygiene and a decontamination bath (i.e. immersed in liquid soap and water temperature > 40 °C). End-of-life waste disposal for several SUP during COVID-19 is expected to be mixed with urban solid waste, as recycling sources are being limited globally. As COVID-19 disease spreads across the globe, the indiscriminate usage and excessive disposal of medical and plastic waste (the majority of which have low biodegradation rates in an open environment) by billions of people are emerging as an increasingly global problem. Tang (2020) also reported the impacts of MCO on waste generation in Penang, Malaysia. It was observed that during MCO, online shopping have increased 3 to 4 times a week (+7%); food delivery increased 1 to 2 times a week (+6%) that ultimately contributed to the growing appetite for single-use of plastics. The use of plastic bags has also increased by 33% followed by food containers (49%), cutleries (31%) and straws (31%) of more than 4 pieces per week.

Medical waste is not the only kind of waste that is rising as a result of the pandemic. COVID-19 has also resulted in a spike in packaging as a result of online shopping and home delivery. There is also a shift in the belief that packaging and single-use plastics possess a “protection” element. Owing to the increased demand on governments to resolve more pressing concerns as a consequence of COVID-19, the emphasis and drive on eliminating waste plastics by different steps such as banning and charging have slowed. Aside from that, plastic disposal has taken a back seat owing to concerns over contaminated waste plastics as well as the lockdown. Some places have restricted waste recycling activities temporarily to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in recycling facilities (Kulkarni and Anantharama 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic impacts the environment both positively and negatively. Studies note that with more people at home, there is less air pollution. This study was designated purposely to investigate variations in the trend and pattern of the MSW before and during the implementation of the MCO in Peninsular Malaysia. Our results indicate that during the early implementation of MCO in Peninsular Malaysia, the volume of MSW showed a steep decrease, especially in the initial phase of containment. Our result provided limited coverage without considering types of waste during MCO. Therefore, the safe management of domestic waste during COVID-19 could be a challenge, as medical waste such as contaminated masks, gloves and used or expired medications can easily be mixed with domestic waste, yet, they must be treated as hazardous waste and disposed of separately to minimize possible environmental effects and to avoid them becoming another source of virus contamination.

In addition, to reduce the environmental impact of MSW during a pandemic, segregation of contaminated and non-contaminated trash at the source is advised, followed by recycling and suitable waste management. This policy should be maintained post-pandemic to reduce environmental and health concerns. Many initiatives are underway to reduce the waste management issues caused by the high volume of MSW generated by the COVID-19 epidemic. As the pandemic progresses, numerous programs are being conducted to improve waste management systems. However, novel ways are required to securely handle infectious trash while minimizing environmental damage. Inclusion of stakeholders from all sectors of waste management systems is critical to formulating sustainable waste management policy. This can help waste management systems withstand future crises. The choice of technology must also take into account waste composition, location and social acceptance.

Conclusions

This study was designed to investigate variation in the trend and pattern of the MSW before and during the implementation of the MCO in Peninsular Malaysia. In conclusion, our results indicate the volume of MSW showed a steep decrease, especially during the implementation of MCO. However the findings provided limited coverage without considering the composition of waste during MCO. One of the factors that may significantly contribute to the waste reduction was the temporary closure of most of the business during MCO. The implementation of the MCO has shown us that our lifestyles can have a powerful impact on our environment. The MCO is currently being continued, and the volume of MSW has shown an increase in the latter MCO phases. The COVID-19 pandemic has already had a tremendous impact on the waste sector. While the pandemic was still progressing and restrictions were still imposed in Malaysia, public authorities and municipal waste operators have had to rapidly adapt their waste management systems and procedures to accommodate this new situation. The current situation offers us an important opportunity for redesigning our social and economic systems while enhancing environmental quality and social inclusiveness.

Data availability

Not applicable

References

Boroujeni M, Saberian M, Li J (2021) Environmental impacts of COVID-19 on Victoria, Australia, witnessed two waves of Coronavirus. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28(11):14182–14191

Caraka RE, Lee Y, Kurniawan R, Herliansyah R, Kaban PA, Nasution BI, Gio PU, Chen RC, Toharudin T, Pardamean B (2020) Impact of COVID-19 large scale restriction on environment and economy in Indonesia. Glob J Environ Sci Manag 6(Special Issue):65–84

Chen Z, Hao X, Zhang X, Chen F (2021) Have traffic restrictions improved air quality? A shock from COVID-19. J Clean Prod 279:123622

da Costa JP, Mouneyrac C, Costa M, Duarte AC, Rocha-Santos T (2020) The role of legislation, regulatory initiatives and guidelines on the control of plastic pollution. Front Environ Sci 8:104

Heidari M, Garnaik PP, Dutta A (2019) The valorization of plastic via thermal means: industrial scale combustion methods. Plast Energy 295–312

Jephcote C, Hansell AL, Adams K, Gulliver J (2021) Changes in air quality during COVID-19 ‘lockdown’ in the United Kingdom. Environ Pollut 272:116011

Jereme IA, Siwar C, Begum RA, Abdul Talib B (2016) Addressing the problems of food waste generation in Malaysia. Int J Adv Appl Sci 3(8):68–77

Karim W, Haque A (2020) The Movement Control Order (MCO) for COVID-19 crisis and its impact on tourism and hospitality sector in Malaysia. Int Tour Hosp J 3(2):1–7

Kenarkoohi A, Noorimotlagh Z, Falahi S, Amarloei A, Mirzaee SA, Pakzad I, Bastani E (2020) Hospital indoor air quality monitoring for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) virus. Sci Total Environ 748:141324

Kulkarni BN, Anantharama V (2020) Repercussions of COVID-19 pandemic on municipal solid waste management: challenges and opportunities. Sci Total Environ 743:140693

Lemanski NJ, Schwab SR, Fonseca DM, Fefferman NH (2020) Coordination among neighbors improves the efficacy of Zika control despite economic costs. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(6):e0007870

Lim WJ, Chin NL, Yusof AY, Yahya A, Tee TP (2016) Food waste handling in Malaysia and comparison with other Asian countries. Int Food Res J 23(December):S1–S6

Mahato S, Pal S, Ghosh KG (2020) Effect of lockdown amid COVID-19 pandemic on air quality of the megacity Delhi India. Sci Total Environ 730:139086

Maleki M, Anvari E, Hopke PK, Noorimotlagh Z, Mirzaee SA (2021) An updated systematic review on the association between atmospheric particulate matter pollution and prevalence of SARS-CoV-2. Environ Res 110898

Manaf LA, Samah MAA, Zukki NIM (2009) Municipal solid waste management in Malaysia: practices and challenges. Waste Manag 29(11):2902–2906

Muhammad S, Long X, Salman M (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and environmental pollution: a blessing in disguise? Sci Total Environ 728:138820

Noorimotlagh Z, Jaafarzadeh N, Martínez SS, Mirzaee SA (2020) A systematic review of possible airborne transmission of the COVID-19 virus (SARS-CoV-2) in the indoor air environment. Environ Res 110612

Noorimotlagh Z, Mirzaee SA, Kalantar M, Barati B, Fard ME, Fard NK (2021) The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in hospital: an insight into environmental surfaces contamination, disinfectants’ efficiency, and estimation of plastic waste production. Environ Res 202:111809

Sharma S, Zhang M, Anshika, Gao J, Zhang H, Kota SH (2020) Effect of restricted emissions during COVID-19 on air quality in India. Sci Total Environ 728:138878

Shekdar AV (2009) Sustainable solid waste management: an integrated approach for Asian countries. Waste Manag 29(4):1438–1448

Silva ALP, Prata JC, Walker TR, Campos D, Duarte AC, Soares AM, ... Rocha-Santos T (2020) Rethinking and optimising plastic waste management under COVID-19 pandemic: policy solutions based on redesign and reduction of single-use plastics and personal protective equipment. Sci Total Environ 742:140565

Tang KHD (2020) Movement control as an effective measure against Covid-19 spread in Malaysia: an overview. J Public Health 1–4

Velavan TP, Meyer CG (2020) The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop Med Int Health 25(3):278–280

Vosoughi M, Karami C, Dargahi A, Jeddi F, Jalali KM, Hadisi, A, ... Mirzaee SA (2021) Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 in hospital indoor air of COVID-19 patients’ ward with impinger method. Environ Sci Pollut Res 1–9

Xanthos D, Walker TR (2017) International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review. Mpb 118:17–26

Xu H, Yan C, Fu Q, Xiao K, Yu Y, Han D, Wang W, Cheng J (2020) Possible environmental effects on the spread of COVID-19 in China. Sci Total Environ 731:139211

Zambrano-Monserrate MA, Ruano MA, Sanchez-Alcalde L (2020) Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci Total Environ 728:138813

Funding

The Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Selangor supported this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This collaboration work was carried out among all the authors. MAB, NCD, NP, HS and SNSI designed the study; MAB and NCD collected the data and performed the analysis, and SA with ARI interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Communicated by Lotfi Aleya.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brohan, M.A., Dom, N.C., Ishak, A.R. et al. An analysis on the effect of coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic movement control order (MCOS) on the solid waste generation in Peninsular Malaysia. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28, 66501–66509 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17049-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17049-6