Abstract

Purpose

Despite unequivocal evidence demonstrating high carbohydrate (CHO) availability improves endurance performance, athletes often report under-eating CHO during competition. Such findings may be related to a lack of knowledge though currently there are no practical or time-efficient tools to assess CHO knowledge in athletes. Accordingly, we aimed to validate a novel questionnaire to rapidly assess endurance athletes’ knowledge of competition CHO guidelines.

Methods

The Carbohydrate for Endurance Athletes in Competition Questionnaire (CEAC-Q) was created by research-active practitioners, based on contemporary guidelines. The CEAC-Q comprised 25 questions divided into 5 subsections (assessing CHO metabolism, CHO loading, pre-event meal, during-competition CHO and recovery) each worth 20 points for a total possible score of 100.

Results

A between-group analysis of variance compared scores in three different population groups to assess construct validity: general population (GenP; n = 68), endurance athletes (EA; n = 145), and sports dietitians/nutritionists (SDN; n = 60). Total scores were different (mean ± SD) in all pairwise comparisons of GenP (17 ± 20%), EA (46 ± 19%) and SDN (76 ± 10%, p < 0.001). Subsection scores were also significantly different between the groups, with mean subsection scores of 3.4 ± 4.7% (GenP), 9.2 ± 5.2% (EA) and 15.2 ± 3.5% (SDN, p < 0.001). Test–retest reliability of the total CEAC-Q was determined in EA (r = 0.742, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Taking ~ 10 min to complete, the CEAC-Q is a new psychometrically valid, practical and time-efficient tool for practitioners to assess athletes’ knowledge of CHO for competition and guide subsequent nutrition intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endurance athletes have been reported to not achieve optimal carbohydrate (CHO) intake for competition despite guidelines with strong scientific evidence supporting the use of optimal CHO intake to enhance endurance performance [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In addition to laboratory-based research, real-world sports nutrition interventions have demonstrated improved performance in endurance athletes when optimal CHO practices are followed [7,8,9]. Given the strong support for optimal CHO practices in laboratory and real-world settings, a reason why athletes do not meet the CHO intake guidelines may be lack of knowledge, but there is currently no tool to quickly and systematically address this to inform and guide athletes’ nutrition coaching.

While increased knowledge or awareness of CHO guidelines may not necessarily translate to a change in behaviour, we do not currently know the levels of knowledge endurance athletes possess on this topic [10]. By systematically assessing athletes’ knowledge of CHO requirements for competition, sports nutrition practitioners could better design, facilitate and evaluate targeted nutrition interventions to address knowledge gaps to ultimately optimise competitive performance [11]. Existing nutrition knowledge questionnaires assessing general and sports-specific nutrition knowledge of athletes are available [12,13,14,15]. However, none of these questionnaires focuses exclusively on current CHO guidelines to assess knowledge and help explain the role between knowledge of CHO guidelines and practice within competition [2]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop and validate a novel questionnaire to systematically and rapidly assess endurance athletes’ key knowledge of CHO requirements for optimal performance in competition.

Methods

Development of the Carbohydrate for Endurance Athletes in Competition Questionnaire (CEAC-Q)

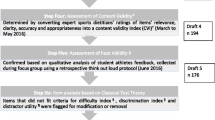

The CEAC-Q was developed by a team of four expert sports dietitians and performance nutritionists leading research on nutrition for endurance performance and working in applied practice with amateur as well as professional endurance athletes ranging from club to world-class level. The questionnaire was formed and based on the current American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines and recent sports nutrition research findings on CHO for endurance sports [2, 16, 17]. Five topic areas of key core knowledge for CHO and competition were identified by the research team, namely: CHO storage and metabolism; CHO loading; CHO meal prior to an event; CHO during an event; and CHO for recovery (Fig. 1). The questionnaire was pilot-tested on sports dietitians and endurance athletes to ensure the questions reflected current CHO guidelines and clarity of instructions during completion, providing qualitative feedback for each question and subsection. The research team reviewed the pilot questionnaire results and incorporated feedback on clarity of questions, suitability, amended and endorsed content and face validity of the final questionnaire.

The final questionnaire (Table 1) consists of demographic questions and 25 multiple-choice questions divided into the 5 key core knowledge areas with a total possible CEAC-Q score of 100. Each question was assigned +4 points for the correct response, +1 for a partial response if there were multiple answers and 0 for incorrect or unsure responses [11, 18]. All questions included an ‘unsure’ option to reduce the possibility of guessing answers and differentiate participants with correct, incorrect or no knowledge. The questionnaire was administered online using SurveyMonkey software (https://www.surveymonkey.com, San Mateo, California, USA) in English with question order presented to participants in a random manner to avoid order bias [19, 20]. Participants were encouraged not to guess and could provide open-ended comments for the overall questionnaire and each individual question to provide opportunity to explain answers or identify need to clarify wording [12]. SurveyMonkey recorded time to complete the questionnaire which could only be completed once without time constraints. Only completed questionnaires were included for analysis.

Construct validity assessment

To assess construct validity, three groups with a priori hypothesised varying levels of sports nutrition knowledge were recruited. In order of expected level of knowledge, these were: (1) general population who did not participate in any endurance sport (GenP), (2) endurance athletes with > 12 months training experience (EA), and (3) sports dietitians/nutritionists (SDN) who were registered members of Sports Dietitians Australia, the Sport and Exercise Nutrition Register, British Dietetic Association Sport Nutrition Group, International Society of Sports Nutrition or Board Certified Specialist in Sports Dietetics with the American Academy of Sports Dietitians and Nutritionists. Participants were invited to participate through social media and email lists of sport nutrition regulatory bodies. All participants were provided with the participation statement and online consent form and agreed to participate electronically.

Test–retest reliability

To assess test–retest reliability, the athlete group were provided with the choice of completing a second questionnaire 10–14 days later based on validation protocols used by previous nutrition knowledge questionnaires for athletes [21, 22]. A period of less than 3 weeks is considered long enough for the questions to be forgotten yet short enough to minimise any change in nutrition knowledge [23]. Athletes who volunteered to complete the questionnaire a second time were contacted by email 10–14 days later with a personalised link to the test–retest questionnaire minus demographic questions. No formal nutrition education was provided or advised between tests. To account for any learning effect after completing all questions in the retest, athletes were asked additional questions regarding learning effect and perceived changes in knowledge or scores (Table 1). Open-ended responses were provided by 26 participants who believed their sports nutrition knowledge had changed to explain how and why it changed between tests. Responses were grouped into four categories; raised awareness of current knowledge gaps, self-directed learning, consultation with a coach or dietitian for advice and rushing or selecting unsure to avoid guessing incorrectly.

Statistics and data analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the total score and the five CHO subsections between groups with post hoc analysis Scheffe due to unequal group sizes. Statistically significant differences in knowledge total and subsection scores between the three groups was seen as evidence of construct validity of the questionnaire [12]. Each of the five subsections was assessed separately for internal consistency as each addressed a different area of CHO knowledge. Internal reliability for each subsection was measured against the psychometric requirements to determine reliability with Cronbach’s α > 0.7 indicating acceptable internal consistency [14, 24]. Differences in knowledge scores between groups were assessed using non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis) analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc analysis to determine which group differed when results were significant. A Bonferroni correction applied to non-parametric post hoc analysis and p values for significance testing set at < 0.017 [21]. Upon retest Pearson’s correlation compared nutrition knowledge scores of athletes between time points to provide evidence of test–retest reliability. With regard to potential learning effects between test- and retest-dependent samples t test were conducted to evidence stability of the CEAC-Q [25]. All data were analysed using IBM SPSS (version 24) with a significance level of p = 0.05. Graphs were created in Graphpad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc. v8, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Participants. Of the 393 participants who commenced, the CEAC-Q was completed by a total of 272 individuals with a completion rate of 69%, consisting of the general population (n = 68), endurance athletes (n = 145) and sports dietitians/nutritionists (n = 60) Table 2. Sports Dietitians and Nutritionists were registered with the UK Sport and Exercise Nutrition Register SENr (n = 35), Sports Dietitians Australia (n = 22) or the American Academy of Sports Dietitians and Nutritionists (n = 3) with < 1 year (n = 7), between 1 and 5 years (n = 31) or > 5-year experience (n = 22).

CEAC-Q scores. There was a significant difference between the groups for total nutrition scores as determined by one-way ANOVA, [F (2, 269) = 172.86, p < 0.0001] (Fig. 2A). In regards the total score of the test, the GenP had the lowest score (17 ± 20, mean ± SD), followed by EA (46 ± 19) with the highest knowledge observed in the SDN group (76 ± 10, p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). Mean subsection scores were also significantly different between the groups for GenP (3.4 ± 4.7), EA (9.2 ± 5.2) and SDN (15.2 ± 3.5, p < 0.001, Fig. 2B–F). No significant differences were observed between subsection scores for any population. EA mean scores were similar for each subsection: CHO storage and metabolism (9.2 ± 5.0); CHO loading (9.4 ± 5.9); CHO meal prior to an event (9.5 ± 5.0); CHO during an event (9.7 ± 4.8); and CHO for recovery (8.1 ± 5.1) with wide inter-participant variation observed in subsection scores between individual athletes.

CEAC-Q total and subsection scores of GenP, endurance athletes (EA) and sport dietitians and nutritionists. Total score (A), carbohydrate metabolism (B), carbohydrate loading (C), carbohydrate pre-event meal (D), carbohydrate during event (E), carbohydrate for recovery (F). Data are means ± SD. Different letters on top of each column represent statistically significant differences between the groups (p < 0.001)

Reliability of the final CEAC-Q as measured by Cronbach’s alpha in the athlete group was 0.82. Reliability scores for the individual CEAC-Q subsections were as follows: CHO metabolism (0.72), CHO loading (0.74), Pre-event CHO meal (0.79), during event CHO (0.85), and Post-event recovery CHO (0.79). All scores were > 0.7 demonstrating acceptable evidence for internal consistency and reliability of each subsection of the questionnaire [14, 24]. Removal of any questions and subsections reduced the internal consistency of the CEAC-Q.

Test–retest reliability. Of the total 145 athletes initially recruited, 59 EA completed a second test. The retest showed a significant learning effect between test (45 ± 20) and retest (53 ± 18, p < 0.001). Test–retest reliability of the total CEAC-Q was determined (r = 0.742, p < 0.001 Table 3), but not for the individual subsections. Scores increased by an average 8.5 ± 13.6 points (p < 0.001, Table 3) with a wide inter-participant variation range in the change. The difference in scores between the initial test was primarily the result of fewer athletes selecting unsure (0 points) in the second test (14.8 ± 9.2 vs 10.6 ± 9.6, p < 0.0001) and choosing an alternative answer that was either incorrect (0 points) or correct (4 points). The majority of athletes (76.3%, n = 45) increased CEAC-Q scores on retest by an average + 13 ± 12 points, while 14 participants’ scores decreased between tests by − 6 ± 4 points. The majority of athletes (91.5%, n = 54) indicated that completing the CEAC-Q inspired them to learn more about sports nutrition, with 72.9% (n = 43) believing their knowledge had increased between tests. Qualitative comments suggest this difference in scores may partially be explained if participants selected unsure to avoid guessing incorrectly in one test but not for the other; “I think I clicked ‘unsure’ more the first time whereas this time I didn’t at all, but I don’t think my knowledge has changed.”. By completing the CEAC-Q that athletes may have been made aware of gaps in their own knowledge which instigated self-learning “After answering “Unsure” on most of the questions the first time round I looked up some of the info online to get a better understanding”. However, as one participant reported increased knowledge or awareness does not necessarily translate to a change in behaviour: “It’s made me think I SHOULD learn more. But whether or not I act on it is questionable.”

Test time to completion. When performing the questionnaire only during retest (without demographics questions), the CEAC-Q took athletes an average 10:36 ± 07:45 min to complete.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that (1) the carbohydrate for endurance athletes in competition questionnaire (CEAC-Q) is a fast and valid tool to assess CHO knowledge for competition in endurance athletes, and (2) the CEAC-Q can identify knowledge gaps and raise awareness of that gap within athletes.

To our knowledge, the CEAC-Q is the first CHO-specific nutrition knowledge questionnaire designed for use with endurance athletes in a competition setting to understand gaps in knowledge of current CHO guidelines. Previous general nutrition knowledge questionnaire studies have observed both poor CHO-specific knowledge in athletes [26] as well as inadequate CHO intakes during competition in elite and amateur athletes [5, 6, 27]. Inadequate nutrition knowledge is one of multiple barriers influencing athletes’ capacity to eat appropriately [28]. A key role of nutrition practitioners is to provide targeted nutrition coaching based upon topics that are poorly understood by their athletes [21]. Using the CEAC-Q to specifically evaluate knowledge of CHO for optimal performance before, during and after competition, it is possible for nutrition practitioners to rapidly identify these knowledge gaps to provide bespoke education during the nutrition-coaching process [29, 30].

Although the CEAC-Q focuses specifically on CHO, knowledge scores were comparable to those of other general sports nutrition knowledge questionnaires conducted in athletes. Two longer original 89-item nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSKQ) [22] and shortened 37-item abridged nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (A-NSKQ) [21] reported nutrition knowledge scores in athletes of 49% and 46%, respectively. Five of seven studies included in a meta-analysis of general nutrition knowledge questionnaires reported athletes with mean knowledge scores greater than 50%, ranging from 42.7 to 67.7% [11]. In a general sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire, Trakman and Forsyth [21] determined construct validity between individuals with formal nutrition education (65%) and individuals with no formal nutrition education score (52%). Karpinski and Dolins [15] found 55.4% of athletes correctly answered a general sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire where out of a total 11 points, athletes scored 3.5 ± 3.0 (31.8%) against sports dietitians 7.8 ± 2.4 (70.9%). Similar to these, the CEAC-Q total scores (Fig. 2A) show that EA had superior nutrition knowledge (46%) than the GenP (17%), but less than SDN (76%). The clear distinction demonstrates construct validity of the CEAC-Q. Future CEAC-Q scores from a large cohort of athletes will identify factors affecting inter-individual variation in knowledge to clarify which topics are poorly understood and how this relates to practice.

An unexpected finding was a small but significant learning effect of the CEAC-Q to allow athletes to self-identify gaps in their own knowledge that may have motivated self-directed learning to fill these knowledge gaps. Indeed, retest of the CEAC-Q 10–14 days after, in a subgroup of 59 EA resulted in an increased test score for 54 athletes (91.5%), with a mean increase in score of 8.5 ± 13.6% (p = < 0.001). This occurred despite no feedback regarding scores or formal education being provided between tests. The majority of athletes reported that their knowledge increased after the initial completion (n = 43, 72.9%) and wanted to learn more about sports nutrition for competition (n = 54, 91.5%). Systematic examination of open-ended comments about the questionnaire made by 26 of the athletes who reported changes in knowledge following in retest questionnaire unveiled athletes becoming aware of gaps in their own knowledge and participated in self-directed learning on the topic or sought external advice. Similarly, qualitative comments indicate that changes in scores may be the result of EA selecting unsure in the first test then selecting an answer in the retest. The act of completing the CEAC-Q may set in chain thinking processes leading to new insights or knowledge [31]. Athletes naturally seek to gain any competitive advantage; becoming aware of gaps in their knowledge may seek to improve between two tests [25]. As scores are expected to increase following self-education, a different and small random error in repeat tests indicates good reliability and construct validity as it suggests learning processes at work [32, 33].

A key role of sports dietitians is to support positive change in the dietary behaviour of athletes utilising a range of nutrition-coaching interventions [29, 30]. In the theoretical framework of the COM-B model of behaviour change, improving the physical and psychological capability and the motivation of individuals are essential to drive behaviour change [34, 35]. Our findings support the idea that using the CEAC-Q as a screening tool could help increase the theoretical and practical knowledge (capability) by identifying gaps in knowledge of current CHO guidelines that may require targeted education. An unexpected finding was the ability of the CEAC-Q to internally motivate an athlete to instigate self-directed learning to correct knowledge gaps, despite no feedback being provided on results. Although increased knowledge or awareness of areas for improvement does not necessarily translate to a change in behaviour [10], a good nutrition-coaching program should enhance enablers and reduce barriers to support change [29]. Thus, the CEAC-Q can be a useful tool for sports dietitians aiming to influence and motivate their athletes to change nutritional intake during competition for optimal performance.

The main limitations of the current questionnaire are the time-frame between tests, control over participant test conditions, self-learning and bias in nutritional beliefs. Previous nutrition knowledge validation studies considered a period of 3 weeks long enough for answers to be forgotten yet short enough to minimise any change in nutrition knowledge [12, 14, 21, 22]. Test conditions should be consistent in repeat trials, however, for a self-administered test, no control could be placed over distractions or how much attention a participant takes when completing [32]. No nutrition education or feedback on scores were provided between tests, however, athletes who participated in the retest may have been personally invested in the topic and more motivated to increase their knowledge, which could not be controlled by investigators [21] and it would have been useful to conduct a formal education program to further test the capacity to detect changes in knowledge.

The current findings open up avenues for future research to assess and optimise dietary practices of endurance athletes. Completing the CEAC-Q with a larger cohort of endurance athletes will allow differentiation between known confounders of nutrition knowledge in a competitive setting: age, sex, level of education as well as potential confounders including living situation, level physical activity, ethnicity, athletic calibre and type of sport [26]. However, as increased knowledge or awareness will not necessarily translate to a change in behaviour [10] future studies should use the CEAC-Q in a competitive setting to assess barriers, attitudes and the relationship between CHO knowledge and practice. This will allow nutrition practitioners to further understand why athletes fail to achieve recommended CHO intakes and subsequently develop more effective, improved athlete nutrition education resources and programs to optimise endurance performance.

Conclusion

The CEAC-Q is a valid online tool taking ~ 10 min to rapidly assess baseline knowledge of current carbohydrate guidelines and recommendations in athletes. Following administration of the CEAC-Q, a small significant learning effect was observed, demonstrating a potential use to identify knowledge gaps prior to targeted nutrition coaching and increase the capability and motivation of athletes to change behaviour. Future studies should evaluate the relationship between CEAC-Q knowledge and carbohydrate intake during competition with a larger cohort to define differences between known confounders of nutrition knowledge.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CEAC-Q:

-

Carbohydrate for Endurance Athletes in Competition Questionnaire

- CHO:

-

Carbohydrate

- EA:

-

Endurance athletes

- GenP:

-

General population

- SDN:

-

Sports dietitians/nutritionists

References

Stellingwerff T, Cox GR (2014) Systematic review: carbohydrate supplementation on exercise performance or capacity of varying durations. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 39(9):998–1011

Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM (2016) Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance. J Acad Nutr Diet 116(3):501–528

Heikura IA et al (2017) A mismatch between athlete practice and current sports nutrition guidelines among elite female and male middle- and long-distance athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 27(4):351–360

Spronk I et al (2015) Relationship between general nutrition knowledge and dietary quality in elite athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 25(3):243–251

McLeman LA, Ratcliffe K, Clifford T (2019) Pre- and post-exercise nutritional practices of amateur runners in the UK: are they meeting the guidelines for optimal carbohydrate and protein intakes? Sport Sci Health 15:511–517

Masson G, Lamarche B (2016) Many non-elite multisport endurance athletes do not meet sports nutrition recommendations for carbohydrates. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41(7):728–734

Hansen EA et al (2014) Improved marathon performance by in-race nutritional strategy intervention. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 24(6):645–655

Hottenrott K et al (2012) A scientific nutrition strategy improves time trial performance by≈ 6% when compared with a self-chosen nutrition strategy in trained cyclists: a randomized cross-over study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37(4):637–645

Mujika I (2018) Case study: long-term low carbohydrate, high fat diet impairs performance and subjective wellbeing in a world-class vegetarian long-distance triathlete. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 29(3):339–344

Alaunyte I, Perry JL, Aubrey T (2015) Nutritional knowledge and eating habits of professional rugby league players: does knowledge translate into practice? J Int Soc Sports Nutr 12:18

Heaney S et al (2011) Nutrition knowledge in athletes: a systematic review. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 21(3):248–261

Blennerhassett C et al (2018) Development and implementation of a nutrition knowledge questionnaire for ultra-endurance athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 29(1):39–45

Trakman GL et al (2019) Modifications to the nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSQK) and abridged nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (ANSKQ). J Int Soc Sports Nutr 16(1):26

Furber MJW, Roberts JD, Roberts MG (2017) A valid and reliable nutrition knowledge questionnaire for track and field athletes. BMC Nutr 3(1):36

Karpinski CA, Dolins KR, Bachman J (2019) Development and validation of a 49-Item sports nutrition knowledge instrument (49-SNKI) for adult athletes. Top Clin Nutr 34(3):174–185

Impey SG et al (2018) Fuel for the work required: a theoretical framework for carbohydrate periodization and the glycogen threshold hypothesis. Sports Med 48:103–1048

Areta JL, Hopkins WG (2018) Skeletal muscle glycogen content at rest and during endurance exercise in humans: a meta-analysis. Sports Med 48(9):2091–2102

Zinn C, Schofield G, Wall C (2005) Development of a psychometrically valid and reliable sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire. J Sci Med Sport 8(3):346–351

Regmi PR et al (2016) Guide to the design and application of online questionnaire surveys. Nepal J Epidemiol 6(4):640–644

Evans RR et al (2009) Developing valid and reliable online survey instruments using commercial software programs. J Consum Health Internet 13(1):42–52

Trakman GL et al (2018) Development and validation of a brief general and sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire and assessment of athletes’ nutrition knowledge. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 15:17

Trakman GL et al (2017) The nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSKQ): development and validation using classical test theory and Rasch analysis. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 14:26

Kline P (2000) The handbook of psychological testing, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Tavakol M, Dennick R (2011) Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ 2:53–55

Kondric M et al (2013) Sport nutrition and doping in tennis: an analysis of athletes’ attitudes and knowledge. J Sports Sci Med 12:290–297

Spendlove JK et al (2011) Evaluation of general nutrition knowledge in elite Australian athletes. Br J Nutr 107(12):1871–1880

Cox GR, Snow RJ, Burke LM (2010) Race-day carbohydrate intakes of elite triathletes contesting olympic-distance triathlon events. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 20(4):299–306

Heaney S et al (2008) Towards an understanding of the barriers to good nutrition for elite athletes. Int J Sports Sci Coach 3(3):391–401

Bentley MR et al (2019) Sports nutritionists’ perspectives on enablers and barriers to nutritional adherence in high performance sport: a qualitative analysis informed by the COM-B model and theoretical domains framework. J Sports Sci 37(18):2075–2085

Bentley MRN, Mitchell N, Backhouse SH (2020) Sports nutrition interventions: a systematic review of behavioural strategies used to promote dietary behaviour change in athletes. Appetite. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104645

Taber KS (2017) The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ 48(6):1273–1296

Batterham AM, George KP (2003) Reliability in evidence-based clinical practice: a primer for allied health professionals. Phys Ther Sport 4(3):122–128

George K, Batterham A, Sullivan I (2000) Validity in clinical research: a review of basic concepts and definitions. Phys Ther Sport 1(1):19–27

Michie S et al (2013) The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 46(1):81–95

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 6:42

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by GS, JP, JM and JA; data were collected and analysed by GS and JA; data interpretation and manuscript preparation were undertaken by GS and JA. All the authors approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Liverpool John Moores ethics committee (application reference: 19SPS016). Written consent for participants and research was conducted according to Helsinki as per the LJMU ethics committee requirements.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants for publication within this journal.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sampson, G., Pugh, J.N., Morton, J.P. et al. Carbohydrate for endurance athletes in competition questionnaire (CEAC-Q): validation of a practical and time-efficient tool for knowledge assessment. Sport Sci Health 18, 235–247 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00799-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00799-8