Abstract

Deliberately training with reduced carbohydrate (CHO) availability to enhance endurance-training-induced metabolic adaptations of skeletal muscle (i.e. the ‘train low, compete high’ paradigm) is a hot topic within sport nutrition. Train-low studies involve periodically training (e.g., 30–50% of training sessions) with reduced CHO availability, where train-low models include twice per day training, fasted training, post-exercise CHO restriction and ‘sleep low, train low’. When compared with high CHO availability, data suggest that augmented cell signalling (73% of 11 studies), gene expression (75% of 12 studies) and training-induced increases in oxidative enzyme activity/protein content (78% of 9 studies) associated with ‘train low’ are especially apparent when training sessions are commenced within a specific range of muscle glycogen concentrations. Nonetheless, such muscle adaptations do not always translate to improved exercise performance (e.g. 37 and 63% of 11 studies show improvements or no change, respectively). Herein, we present our rationale for the glycogen threshold hypothesis, a window of muscle glycogen concentrations that simultaneously permits completion of required training workloads and activation of the molecular machinery regulating training adaptations. We also present the ‘fuel for the work required’ paradigm (representative of an amalgamation of train-low models) whereby CHO availability is adjusted in accordance with the demands of the upcoming training session(s). In order to strategically implement train-low sessions, our challenge now is to quantify the glycogen cost of habitual training sessions (so as to inform the attainment of any potential threshold) and ensure absolute training intensity is not compromised, while also creating a metabolic milieu conducive to facilitating the endurance phenotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Periodically completing endurance training sessions (e.g. 30–50% of training sessions) with reduced carbohydrate (CHO) availability modulates the activation of acute cell signalling pathways (73% of 11 studies), promotes training-induced oxidative adaptations of skeletal muscle (78% of 9 studies) and, in some instances, improves exercise performance (although only 37% of 11 studies demonstrated performance improvements). |

We propose the presence of a muscle glycogen threshold whereby exceeding a critical absolute level of glycogen depletion during training is especially potent in modulating the activation of acute and chronic skeletal muscle adaptations associated with ‘train low’. |

Future research should attempt to quantify the glycogen and CHO cost of endurance athletes’ typical training sessions so as to increase our understanding of the exercise conditions that may elicit the proposed glycogen threshold and thereby inform practical application of ‘fuel for the work required’ paradigm. |

1 Introduction

The principle of ensuring sufficient carbohydrate (CHO) availability before, during and after training and competition is widely recognized as the fundamental nutritional priority for athletic populations. Indeed, the foundation of current sport nutrition guidelines [1] were developed by Scandinavian researchers in the late 1960s with the introduction of the muscle biopsy technique [2,3,4,5] and the classical ‘super-compensation’ model of CHO loading. In another landmark study in 1981, Sherman and colleagues [6] observed similar magnitudes of glycogen super-compensation with a less severe protocol (i.e., without the exhaustive exercise and CHO restriction phase), whereby several days of a combined exercise taper and moderate CHO intake (e.g. 5 g kg−1 body mass) is followed by 3 days of higher CHO intake (8 g kg−1 body mass). While these data have practical application from a precompetition perspective, one of the most overlooked components of this study is that no differences in half-marathon running performance (as completed on an outdoor 220 m running track) were observed between trials, despite differing pre-exercise muscle glycogen status. The authors allude to this finding when discussing their data:

“The performance times indicate that carbohydrate loading was of no benefit to performance during the 20.9 km run. In fact, performance times were actually slower in the trials with higher levels of muscle glycogen. This suggests that anything above a minimal level of muscle glycogen is unnecessary for performance of a given intensity and duration. More importantly, the practical question may not be how much can I super-compensate but rather, does my diet contain enough carbohydrate to maintain adequate stores of muscle glycogen on a day-to-day basis for training and performance runs?” (p. 117).

In addition to competitive performance, the same lead author subsequently challenged the concept that insufficient daily CHO intake on consecutive training days reduces muscle glycogen availability to a level that impairs training capacity [7, 8]. While such sentiments are undoubtedly dependent on the prescribed training workloads, almost 30 years later the above interpretation and insight appears more relevant than ever. Indeed, with the introduction of molecular biology techniques into the sport and exercise sciences, we are now in the era of ‘nutrient-gene interactions’ whereby the nutritional modulation of endurance training adaptation is a contemporary area of investigation. Since the seminal work of Hansen et al. [9] suggested that some adaptations to physical activity may require a ‘cycling’ of muscle glycogen stores, the role of glycogen availability as a training regulator has gained increased popularity among athletic circles [10]. This body of work has largely focused on the efficacy of the periodic ‘train low (smart), compete high’ paradigm whereby selected training sessions are deliberately completed with reduced CHO availability so as to activate molecular pathways that regulate skeletal muscle adaptation (see Fig. 1). In contrast, it is recommended that both key training sessions and competition always be undertaken with high CHO availability so as to promote performance and recovery [11, 12]. Nonetheless, the optimal approach for which to practically apply periods of ‘train low’ (now commonly referred to as CHO periodization) into an overall athletic training programme is not currently understood.

Schematic overview of the potential exercise-nutrient-sensitive cell signalling pathways regulating the enhanced mitochondrial adaptations associated with training with low CHO availability. (1) Reduced muscle glycogen enhances both AMPK and p38MAPK phosphorylation that results in (2) activation and translocation of PGC-1α and p53 to the mitochondria and nucleus. (3) Upon entry into the nucleus, PGC-1α co-activates additional transcription factors (i.e. NRF1/2) to increase the expression of COX subunits and Tfam, as well as autoregulating its own expression. In the mitochondria, PGC-1α co-activates Tfam to coordinate regulation of mtDNA, and induces expression of key mitochondrial proteins of the electron transport chain, e.g. COX subunits. Similar to PGC-1α, p53 also translocates to the mitochondria to modulate Tfam activity and mtDNA expression, and to the nucleus where it functions to increase expression of proteins involved in mitochondrial fission and fusion (DRP-1 and MFN-2) and electron transport chain proteins. (4) Exercising in conditions of reduced CHO availability increases adipose tissue and intramuscular lipolysis via increased circulating adrenaline concentrations. (5) The resulting elevation in FFA activates the nuclear transcription factor, PPARδ, to increase expression of proteins involved in lipid metabolism, such as CPT1, PDK4, CD36 and HSL. (6) However, consuming pre-exercise meals rich in CHO and/or CHO during exercise can downregulate lipolysis (thereby negating FFA-mediated signalling), as well as reducing both AMPK and p38MAPK activity, thus having negative implications for downstream regulators. (7) High-fat feeding can also modulate PPARδ signalling and upregulate genes with regulatory roles in lipid metabolism (and downregulate CHO metabolism), although high-fat diets may also reduce muscle protein synthesis via impaired mTOR-p70S6K signalling, despite feeding leucine-rich protein. 4EBP1 eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1, AMPK AMP-activated protein kinase, CHO carbohydrate, CD36 cluster of differentiation 36, COX cytochrome c oxidase, CPT1 carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1, Drp1 dynamin-related protein 1, FA fatty acid, FABP fatty acid binding protein, GLU glucose, GLUT4 glucose transporter type 4, HSL hormone-sensitive lipase, IMTG intramuscular triglycerides, LAT1 large neutral amino acid transporter, LEU leucine, Mfn2 mitofusion-2, mTORC1 mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, p38MAPK p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, p53 tumor protein 53, p70S6K ribosomal protein S6 kinase, PDK4 pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4, PGC-1α peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α, PPARδ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, Tfam mitochondrial transcription factor A

Accordingly, the aim of this article is to present a contemporary overview of CHO periodization strategies for training from both a theoretical and practical perspective. We begin by outlining the effects of various train-low paradigms on modulating cell signalling pathways, training adaptations and exercise performance. We then present our rationale for the ‘glycogen threshold hypothesis’, a window of absolute muscle glycogen concentration of which training sessions could be commenced within so as to provide a metabolic milieu that is conducive to modulating cell signalling. We close by presenting a practical model of CHO periodization according to the principle of ‘fuel for the work required’. As opposed to chronic periods of CHO restriction, this model suggests that CHO availability should be manipulated day-to-day and meal-by-meal according to the intensity, duration and specific training goals. With this in mind, we define CHO availability as the sum of the endogenous (i.e., muscle and liver glycogen) and exogenous CHO (i.e. CHO consumed before and/or during exercise) that is available to sustain the required training intensity and duration. According to this definition, it is possible to have insufficient CHO availability (even if exercise is commenced with high pre-exercise muscle glycogen stores) if an inadequate dose of CHO is consumed during exercise to sustain the desired workload [13]. Alternatively, it is possible to commence exercise with reduced muscle glycogen yet still be considered to have sufficient CHO availability if the exogenous CHO consumed during exercise permits the completion of the required training intensity and duration [14].

2 Carbohydrate (CHO) Restriction Enhances Cell Signalling and Gene Expression, and Modulates Components of Training Adaptation and Exercise Performance

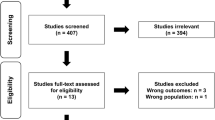

Researchers have used a variety of acute and chronic train-low interventions to investigate the efficacy of CHO restriction and periodization on training adaptations and exercise performance. An overview of specific train-low models is discussed below and relevant experimental details from seminal studies are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, key outcomes from such studies are also categorized under the measures of cell signalling, gene expression, enzymatic changes and performance outcomes, according to positive changes, no change or negative changes (see Table 2). Despite the evidence supporting enhanced skeletal muscle adaptations with CHO restriction, it is noteworthy that such adaptations do not always translate to improved exercise performance.

2.1 Twice Per Day Training

On the basis that reduced pre- [15] and post-exercise [16] muscle glycogen availability augments expression of genes regulating substrate utilization and mitochondrial biogenesis, initial training studies adopted a ‘training twice every second day versus once daily’ research design. In this approach, subjects complete a morning training session to reduce muscle glycogen followed by several hours of reduced CHO intake so that the second training session of the day is commenced with reduced muscle glycogen. Using this model, 3–10 weeks of ‘train low’ increases oxidative enzyme activity [9, 17,18,19], whole body [17, 19] and intramuscular lipid utilization [19] and improves exercise capacity [9] and performance [20]. It is difficult to ascertain if the enhanced training response is mediated by the upregulation of transcriptional responses induced by CHO restriction in recovery from the morning exercise session and/or the enhanced cell signalling responses [21,22,23,24] associated with commencing the afternoon training session with reduced muscle glycogen. In addition to low glycogen availability, there may also be compounding effects of stacking training sessions in close temporal proximity where altering the mechanical, metabolic and hormonal environment may also modulate the enhanced training response. Notwithstanding a potential reduction in absolute training intensity in the afternoon session [17], the twice per day model provides a practical framework whereby the accumulative total time with reduced muscle glycogen is increased. Depending on the length of the interval between the first and second session (i.e. recover low) and the actual duration of the second training session (i.e. train low), the accumulated low glycogen period could range from 3 to 8 h.

2.2 Fasted Training

Exercising fasted represents a simpler model of ‘train low’ whereby breakfast is consumed after a morning training session. In this model, pre-exercise muscle glycogen is not different between fasted or fed conditions, but liver glycogen and circulating glucose is higher during fed conditions. In contrast, increased free fatty acid (FFA) availability and lipid oxidation occur in fasted conditions when exercise is matched for intensity, duration and work performed [25]. Depending on the timing of CHO feeding in relation to the commencement of exercise (e.g. > 60 min before exercise versus < 10 min before and/or during exercise), such differences in FFA availability may manifest from the beginning of exercise [25] or not until after 30–40 min of exercise, respectively [26]. Exercising fasted increases AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity [27] and post-exercise gene expression [28, 29], while several weeks of fasted training increases oxidative enzyme activity [30], lipid transport protein content [31] and resting glycogen storage [32]. However, it is noteworthy that such adaptations are likely regulated via CHO restriction as opposed to true fasted conditions. Indeed, consuming approximately 20 g of whey protein before and during CHO-restricted training sessions still permits mobilization of FFAs [33] and activation of the AMPK signalling axis [34], while also improving net muscle protein balance [35].

2.3 Sleep Low, Train Low

In the ‘sleep low, train low’ model, participants perform an evening training session, restrict CHO during overnight recovery, and then complete a fasted training session the following morning. The accumulative total time with reduced muscle glycogen could therefore extend to 12–14 h depending on the timing and duration of the training sessions and sleep period. Acute models of ‘sleep low, train low’ (where morning exercise is commenced with glycogen < 200 mmol/kg dw) enhance the activation of AMPK, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38) and tumour protein p53 (p53) signalling [36,37,38], although responses are attenuated if trained cyclists complete a morning steady-state session (thus suggesting that both intensity and training status are important) where pre- and post-exercise glycogen content is 350 and 250 mmol/kg dw, respectively [39]. Using a sleep-low model similar to that used by Lane and colleagues [39], Marquet et al. [40, 41] observed that 1–3 weeks of sleep-low training in elite triathletes and cyclists improves cycling efficiency (3.1%), 20 km cycling time-trial performance (3.2%) and 10 km running performance (2.9%) compared with traditional train-high approaches. At present, the extent of CHO restriction required to elicit conditions considered best representative of ‘sleep low’ are not well-defined. However, it is noteworthy that studies demonstrating beneficial effects on cell signalling [38] and performance adaptations [40, 41] have completely restricted CHO after the evening training session and after subjects were fed a protein-only meal or beverage. Nonetheless, similar to other train-low models, the sleep-low paradigm is subject to the obvious limitations of lack of a placebo controlled, double-blinded design. Such limitations are particularly relevant where performance improvements have been observed with only three sessions of ‘sleep low, train low’ [41].

2.4 High-Fat Feeding

In addition to manipulating CHO availability, it is possible that associated elevations in circulating FFA availability also regulate relevant cell signalling pathways. Indeed, the exercise-induced activation of p38MAPK is suppressed with pharmacological ablation of FFA availability [42]. Nonetheless, while we acknowledge the potential role of acute FFA-mediated signalling (as occurring secondary to the primary intervention of CHO manipulation), it is unlikely that CHO restriction in combination with chronic high-fat feeding is beneficial for training adaptations. Indeed, 1–5 days of high-fat feeding reduces the expression [43] and activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex [44], ultimately impairing CHO oxidation and high-intensity performance. Furthermore, Burke et al. [45] observed that exercise economy and performance were negatively impacted in elite race walkers following 3 weeks of a high-fat diet when compared with periodized and high CHO availability. Emerging data also suggest that high-fat feeding may impair muscle protein synthesis [46], potentially via reduced activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) signalling [43].

2.5 Amalgamation of Train-Low Paradigms and CHO Restriction-Induced Calorie Restriction

In the real-world environments of elite endurance athletes, it is likely that athletes practice an amalgamation of the aforementioned train-low paradigms (either through default of their current training structure or via coach and sport scientist-led practices), as opposed to undertaking one strategy in isolation. Additionally, elite athletes may also undertake 20–30 h of training per week, whereas many of the study designs reviewed thus far have utilized training programmes of < 10 h per week. The complexity of practical train-low models is exacerbated by observations that endurance athletes practice day-to-day or longer-term periods of energy periodization (as opposed to CHO per se) in an attempt to reduce body and fat mass in preparation for competition [10, 47] (Morton, unpublished observations). Indeed, the performance improvements observed by Marquet et al. [40] were also associated with a 1 kg reduction in fat mass induced by the sleep-low model. Notwithstanding reductions in body mass, it is indeed possible that many of the skeletal muscle adaptations associated with ‘train low’ are mediated by repeated and transient periods of energy restriction as opposed to CHO restriction per se. We observed that the post-exercise expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α), p53, mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) messenger RNA (mRNA) were elevated with similar magnitude and time-course when a low CHO and high-fat diet was consumed versus an isoenergetic high-CHO feeding strategy [43]. Such data conflict with previous observations from our laboratory [38], where post-exercise CHO and calorie restriction augments the expression of many of the aforementioned genes. Given the similarities in metabolic adaptation to both CHO and calorie restriction, such data raise the question as to whether the enhanced mitochondrial responses observed when training low are actually due to transient periods of calorie restriction (as mediated by a reduction in CHO intake) as opposed to CHO restriction per se. This point is especially relevant given that many endurance athletes present daily with transient periods of both CHO and calorie restriction due to multiple training sessions per day, as well as longer-term periods of suboptimal energy availability [47].

3 The Glycogen Threshold Hypothesis: Muscle and Performance Adaptations Associated with CHO Restriction Occur Within a Range of Absolute Muscle Glycogen Concentrations

Given that the enhanced training response associated with ‘train low’ is potentially mediated by muscle glycogen availability, it is prudent to consider the absolute glycogen concentrations required to facilitate the response. In this regard, examination of available train-low studies (see Table 1) demonstrates that adaptations associated with CHO restriction are particularly evident when absolute pre-exercise muscle glycogen concentrations are ≤ 300 mmol/kg dw. However, restoring post-exercise glycogen levels to > 500 mmol/kg dw attenuates exercise-induced changes in gene expression [16], and keeping glycogen (and energy) at critically low post-exercise levels (i.e. < 100 mmol/kg dw) may reduce the regulation of protein synthesis pathways [48]. CHO feeding during exercise also attenuates AMPK-mediated signalling but only when glycogen sparing occurs [27, 49]. However, it should be noted that commencing exercise with < 200 mmol/kg dw is likely to impair training intensity due to the lack of muscle substrate and impact on the contractile capacity of muscle cells via impaired calcium regulation [50,51,52]. Additionally, repetitive daily training in the face of a reduction in CHO availability (so as to reduce pre-exercise muscle glycogen concentration) may increase susceptibility to illness [53]. On this basis, such data suggest the presence of a muscle glycogen threshold whereby a critical absolute level of glycogen depletion must be induced for significant activation of cell signalling pathways to occur on the proviso, of course, that the desired training workload and intensity can be completed without any maladaptations. In this way, the glycogen threshold provides a metabolic window of muscle glycogen concentrations (e.g. 300–100 mmol/kg dw) that is permissive to facilitating the required training intensity, acute cell signalling responses and post-exercise remodelling processes (see Fig. 2). Nonetheless, the potential presence of a glycogen threshold is not to say that individuals will not adapt to endurance training if they do not exercise within a suggested threshold. Rather, such a threshold illustrates the possibility that the enhanced adaptations associated with ‘train low’ are especially prominent once a certain level of glycogen depletion has occurred. We also acknowledge the between-subject variations in glycogen depletion that is often observed within the literature, and how this may also influence any potential glycogen threshold range (individual subject responses are also displayed in Fig. 2 for the data presented from the authors’ laboratory).

Overview of studies supporting the glycogen threshold hypothesis. Studies are categorized into those examining a cell signalling, b gene expression and c muscle contractile capacity and post-exercise signalling. In a and b, the green bars represent the trial within the specific study that has been completed with high muscle glycogen, and the red bars represent the trial completed with low muscle glycogen. The length of the bar in both instances corresponds to the pre- and post-exercise muscle glycogen concentration. Additionally, in studies from the authors’ laboratory (Bartlett et al. [38] and Impey et al. [48]), black and white circles represent individual subjects’ pre- and post-exercise muscle glycogen concentrations, respectively. In c, a variety of CHO manipulation protocols have been adopted to examine the effect of high (green bars) and low (red bars) muscle glycogen concentration on contractile properties and post-exercise cell signalling. The shaded area represents a potential muscle glycogen threshold in which exercise should be commenced (albeit specific to the training status of the participants studied in these investigations). AMPK AMP-activated protein kinase, ACC acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Ca2+ calcium, COX cytochrome c oxidase, p38MAPK p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, p70S6K ribosomal protein S6 kinase, PDK4 pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4, PGC-1α peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α, Tfam mitochondrial transcription factor A

4 Fuel for the Work Required: Practical Application of the Glycogen Threshold Hypothesis

The studies reviewed thus far have typically adopted matched work exercise protocols whereby CHO availability is manipulated prior to training sessions consisting of identical intensity, duration and work performed. More recently, we also adopted an experimental design in which participants completed an exhaustive exercise capacity test in conditions of high or low pre-exercise muscle glycogen (600 and 300 mmol/kg dw, respectively) [48]. All participants cycled for longer in the high trial versus the low trial, with average exercise capacity increased by 60 min. We observed identical cell signalling and post-exercise gene responses between trials (e.g. AMPK-PGC-1α) despite the completion of less work performed in the low glycogen trial. However, it is acknowledged that to stimulate other endurance-related adaptations (e.g. central changes such as cardiac hypertrophy), high glycogen conditions would be superior, given that it would allow for the completion of more work performed and, of course, an elevated heart rate for a much longer training duration. Moreover, at the muscular level it appears that commencing exercise with high muscle glycogen requires the completion of considerably more work in order to elicit comparable cell signalling and muscle remodelling responses than those occurring when exercise is commenced with low muscle glycogen. In this situation, it is suggested that subjects eventually surpass a critical level of glycogen depletion, thereby completing a proportion of exercise within the glycogen threshold required to stimulate cell signalling. Given that elite endurance athletes rarely complete identical sessions or train with maximal intensity (or to exhaustion) on consecutive training sessions, either within or between days, such data support the concept of ‘fuelling for the work required’, whereby CHO availability is adjusted in accordance with the demands of the specific training session to be completed. In this way, absolute daily CHO intake and distribution can be modified so that key sessions are performed within or close to the suggested muscle glycogen threshold. As initially alluded to by Sherman et al. [6], the question that emerges therefore is not how much an athlete can super-compensate their glycogen stores but rather does the athlete’s diet contain enough CHO to maintain training intensity while also creating a consistent metabolic milieu that is conducive to facilitating training adaptations. Using the sport of road cycling, we present a theoretical overview of the model in Table 3.

5 Critical Reflections and Limitations on Practical Application of the Glycogen Threshold Hypothesis

Despite the theoretical rationale for periodic train-low sessions and the potential presence of a glycogen threshold, there are many obvious challenges in bringing this to life in applied practice. Crucially, our understanding of the glycogen and CHO cost of the habitual training sessions undertaken by elite athletes is not well known, thus limiting our ability to prescribe training sessions that may elicit any glycogen threshold. Indeed, rates of glycogen utilization are not linear and are dependent on substrate availability, training status, intensity and duration, all of which can modify the regulation of glycogenolysis via hormonal control or allosteric regulation. Furthermore, any potential glycogen threshold is also likely to be training-status-specific and heavily dependent on the characteristics of the exercise modality in question, e.g. a lower absolute threshold may be present for a metabolically based sport such as cycling (non-weight-bearing activity with a lower eccentric load), whereas a higher threshold may be present in running, given that weight bearing, eccentric contractions and higher neuromuscular loads are present. While examination of relevant studies (see Fig. 3 for a sampling of experimental data from cycling studies) provides some indication of the intensity and duration (against a background of differences in pre-exercise glycogen status) that would be required to sufficiently deplete an athlete’s glycogen close to or within the glycogen threshold, considerable assumptions must be made. Indeed, given the lack of technology available to non-invasively quantify muscle glycogen, practical application of the glycogen threshold hypothesis relies heavily on practitioners’ theoretical knowledge of glycogen utilization with their specific sport and, moreover, detailed assessment of an athlete’s previous day(s) training loads and macronutrient intake in order to formulate appropriate guidance for future training sessions. To this end, awareness of relevant sport-specific literature coupled with both external (e.g. power outputs, running velocities) and internal (e.g. heart rate, blood lactate, ratings of perceived exertion) assessment of training load can be collectively used in conjunction with laboratory assessments of substrate utilization so as to estimate the potential CHO cost of real-world training sessions. Considerable debate is also likely to exist among researchers and practitioners as to what amount of dietary CHO actually equates to the red, amber and green (RAG) ratings outlined in Table 3, and, undoubtedly, further sport-specific studies are warranted.

Muscle glycogen utilization according to studies incorporating varied exercise intensity, duration, and pre-exercise muscle glycogen concentration. Such data illustrate how the pattern of glycogen use can vary (according to the interactive effects of the aforementioned parameters) and how this should be considered in relation to the proposed glycogen threshold (shaded area). Data represent a sampling from studies compiled from cycling exercise protocols only and represent glycogen use in the vastus lateralis muscle

6 Conclusions

The emergence of CHO availability (specifically muscle glycogen concentration) as a regulator of training adaptation is now an accepted area of research that has practical implications for athlete training strategies. While this is a hot topic among athletes, coaches and sport scientists, the optimal periodization strategy to implement periods of CHO restriction into an overall training programme is not well understood. Furthermore, practical models of CHO (and energy) periodization are likely to be highly specific to the training structure and culture of the sport in question, as well as the athlete’s specific training goals. Accordingly, we have merely presented a hypothetical framework of fuelling for the work required to illustrate how isolated train-low models can be amalgamated to produce day-by-day and meal-by-meal manipulation of CHO availability. While we readily acknowledge the requirement for sport-specific models and long-term training studies (especially to demonstrate if train-low muscle adaptations actually correspond to meaningful changes in exercise performance), we also pose several fundamental questions that are relevant across many sporting models. First, does the presence of a ‘graded’ muscle glycogen threshold really exist, and, if so, how is this affected by training status? Second, should train-low sessions always be left to low-intensity-type sessions or is it the deliberate completion of a high-intensity session (even at the expense of a potential reduction in absolute workload) that is really required to create the metabolic milieu that is conducive to signalling? Third, what is the minimal CHO intake and glycogen concentration required to facilitate periods of ‘train low’ without compromising absolute training intensity during specific sessions? Fourth, is the enhanced training response associated with ‘train low’ regulated by CHO and/or energy restriction, and, if the latter, how do we periodize and structure such training interventions without inducing maladaptations? Finally, are there novel molecular targets and protein modifications/localization that also contribute to the regulation of nutrient and exercise sensitive pathways? When considered this way, it is remarkable that the study of only 500 g of substrate (the approximate whole-body storage of CHO) remains as exciting as ever.

References

Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. American college of sports medicine joint position statement. nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:543–68.

Bergstrom J, Hermansen L, Hultman E, Saltin B. Diet, muscle glycogen and physical performance. Acta Physiol Scand. 1967;71:140–50.

Bergstrom J, Hultman E. Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: an enhancing factor localized to the muscle cells in man. Nature. 1966;16:309–10.

Bergstrom J, Hultman E. The effect of exercise on muscle glycogen and electrolytes in normals. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1966;18:16–20.

Hermansen L, Hultman E, Saltin B. Muscle glycogen during prolonged severe exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 1967;71:129–39.

Sherman WM, Costill DL, Fink WJ, Miller JM. Effect of exercise-diet manipulation on muscle glycogen and its subsequent utilization during performance. Int J Sports Med. 1981;2:114–8.

Sherman WM, Wimer GS. Insufficient dietary carbohydrate during training? Does it impair athletic performance? Int J Sport Nutr. 1991;1:28–44.

Sherman WM, Doyle JA, Lamb DR, Strauss RH. Dietary carbohydrate, muscle glycogen, and exercise performance during 7 days of training. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57:27–31.

Hansen AK, Fischer CP, Plomgaard P, Andersen JL, Saltin B, Pedersen BK. Skeletal muscle adaptation: training twice every second day vs. training once daily. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:93–9.

Stellingwerff T. Case Study: nutrition and training periodization in three elite marathon runners. Int J Sport Nutri Exerc Metab. 2012;22:392–400.

Hawley JA, Morton JP. Ramping up the signal: promoting endurance training adaptation in skeletal muscle by nutritional manipulation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41:608–13.

Bartlett JD, Hawley JA, Morton JP. Carbohydrate availability and exercise training adaptation: too much of a good thing? Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15:3–12.

Coyle EF, Coggan AR, Hemmert MK, Ivy JL. Muscle glycogen utilization during strenuous exercise when fed carbohydrate. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61:165–72.

Wildrick JJ, Costill DL, Fink WJ, Hickey MS, McConnell GK, Tanaka H. Carbohydrate feedings and exercise performance: effect of initial muscle glycogen concentration. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2998–3005.

Pilegaard H, Keller C, Steensberg A, Helge JW, Pedersen BK, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Influence of pre-exercise muscle glycogen content on exercise-induced transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes. J Physiol. 2002;541:261–71.

Pilegaard H, Osada T, Andersen LT, Helge JW, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Substrate availability and transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes in human skeletal muscle during recovery from exercise. Metabolism. 2005;54:1048–55.

Yeo WK, Paton CD, Garnham AP, Burke LM, Carey AL, Hawley JA. Skeletal muscle adaptation and performance responses to once versus twice every second day endurance training regimens. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1462–70.

Morton JP, Croft L, Bartlett JD, MacLaren DP, Reilly T, Evans L, McArdle A, Drust B. Reduced carbohydrate availability does not modulate training-induced heat shock protein adaptations but does up regulate oxidative enzyme activity in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1513–21.

Hulston CJ, Venables MC, Mann CH, Martin C, Philp A, Baar K, Jeukendrup AE. Training with low muscle glycogen enhances fat metabolism in well-trained cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:2046–55.

Cochran AJ, Myslik F, Maclnnis MJ, Percival ME, Bishop D, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. Manipulating carbohydrate availability between twice-daily sessions of high-intensity interval training over 2 weeks improves time-trial performance. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015;25:463–70.

Steinberg GR, Watt MJ, McGee SL, Chan S, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA, Stapleton D, Kemp BE. Reduced glycogen availability is associated with increased AMPKalpha2 activity, nuclear AMPKalpha2 protein abundance, and GLUT4 mRNA expression in contracting human skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31:302–12.

Cochran AJ, Little JP, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. Carbohydrate feeding during recovery alters the skeletal muscle metabolic response to repeated sessions of high-intensity interval exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:628–36.

Yeo WK, McGee SL, Carey AL, Paton CD, Garnham AP, Hargreaves M, Hawley JA. Acute signalling responses to intense endurance training commenced with low or normal muscle glycogen. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:351–8.

Psilander N, Frank P, Flockhart M, Sahlin K. Exercise with low glycogen increases PGC-1a gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:951–63.

Horowitz JF, Mora-Rodriguez R, Byerley LO, Coyle EF. Lipolytic suppression following carbohydrate ingestion limits fat oxidation during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:768–75.

Arkinstall MJ, Bruce CR, Nikolopoulos V, Garnham AP, Hawley JA. Effect of carbohydrate ingestion on metabolism during running and cycling. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2125–34.

Akerstrom TCA, Birk JB, Klein DK, Erikstrup C, Plomgaard P, Pedersen BK, Wojtaszewski J. Oral glucose ingestion attenuates exercise-induced activation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase in human skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:949–55.

Civitarese AE, Hesselink MK, Russell AP, Ravussin E, Schrauwen P. Glucose ingestion during exercise blunts exercise-induced gene expression of skeletal muscle fat oxidative genes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:1023–9.

Cluberton LJ, McGee SL, Murphy RM, Hargreaves M. Effect of carbohydrate ingestion on exercise-induced alterations in metabolic gene expression. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1359–63.

Van Proeyen K, Szlufcik K, Nielens H, Ramaekers M, Hespel P. Beneficial metabolic adaptations due to endurance exercise training in the fasted state. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:236–45.

De Bock K, Derave W, Eijnde BO, Hesselink MK, Koninckx E, Rose AJ, Schrauwen P, Bonen A, Richter EA, Hespel P. Effect of training in the fasted state on metabolic responses during exercise with carbohydrate intake. J Appl Phyiol. 2008;104:1045–55.

Nybo L, Pedersen K, Christensen B, Aagaard P, Brandt N, Kiens B. Impact of carbohydrate supplementation during endurance training on glycogen storage and performance. Acta Physiol. 2009;197:117–27.

Impey SG, Smith D, Robinson AL, Owens DJ, Bartlett JD, Smith K, Limb M, Tang J, Fraser WD, Close GL, Morton JP. Leucine-enriched protein feeding does not impair exercise-induced free fatty acid availability and lipid oxidation: beneficial implications for training in carbohydrate-restricted states. Amino Acids. 2015;47:407–16.

Taylor C, Bartlett JD, van de Graaf CS, Louhelainen J, Coyne V, Iqbal Z, MacLaren DP, Gregson W, Close GL, Morton JP. Protein ingestion does not impair exercise-induced AMPK signalling when in a glycogen-depleted state: implications for train-low compete-high. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:1457–68.

Hulston CJ, Wolsk E, Grøndahl TS, Yfanti C, Van Hall G. Protein intake does not increase vastus lateralis muscle protein synthesis during cycling. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1635–42.

Wojtaszewski JF, MacDonald C, Nielsen JN, Hellsten Y, Hardie DG, Kemp BE, Kiens B, Richter EA. Regulation of 5′AMP-activated protein kinase activity and substrate utilization in exercising human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E812–22.

Chan S, McGee SL, Watt MJ, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA. Altering dietary nutrient intake that reduces glycogen content leads to phosphorylation of nuclear p38 MAP kinase in human skeletal muscle: association with IL-6 gene transcription during contraction. FASEB J. 2004;18:1785–7.

Bartlett JD, Louhelainen J, Iqbal Z, Cochran AJ, Gibala MJ, Gregson W, Close GL, Drust B, Morton JP. Reduced carbohydrate availability enhances exercise-induced p53 signalling in human skeletal muscle: implications for mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:450–8.

Lane SC, Camera DM, Lassiter DG, Areta JL, Bird SR, Yeo WK, Jeacocke NA, Krook A, Zierath JR, Burke LM, Hawley JA. Effects of sleeping with reduced carbohydrate availability on acute training responses. J Appl Physiol. 2015;119:643–55.

Marquet LA, Brisswalter J, Louis J, Tiollier E, Burke LM, Hawley JA, Hausswirth C. Enhanced endurance performance by periodization of carbohydrate intake: “Sleep low” strategy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:663–72.

Marquet LA, Hausswirth C, Molle O, Hawley JA, Burke LM, Tiollier E, Brisswalter J. Periodization of carbohydrate intake: short-term effect on performance. Nutrients. 2016;8:755.

Zbinden-Foncea H, van Loon LJ, Raymackers JM, Francaux M, Deldicque L. Contribution of nonesterified fatty acids to mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in human skeletal muscle during endurance exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013;23:201–9.

Hammond KM, Impey SG, Currell K, Mitchell N, Shepherd SO, Jeromson S, Hawley JA, Close GL, Hamilton LD, Sharples AP, Morton JP. Postexercise high-fat feeding suppresses p70S6K1 activity in human skeletal muscle. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2016;48:2108–17.

Stellingwerff T, Spriet LL, Watt MJ, Kimber NE, Hargreaves M, Hawley JA, Burke LM. Decreased PDH activation and glycogenolysis during exercise following fat adaptation with carbohydrate restoration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:380–8.

Burke LM, Ross ML, Garvican-Lewis LA, Welvaert M, Heikura IA, Forbes SG, Mirtschin JG, Cato LE, Strobel N, Sharma AP, Hawley JA. Low carbohydrate, high fat diet impairs exercise economy and negates the performance benefit from intensified training in elite race walkers. J Physiol. 2017;595:2785–807.

Stephens FB, Chee C, Wall BT, Murton AJ, Shannon CE, van Loon LJ, Tsintzas K. Lipid-induced insulin resistance is associated with an impaired skeletal muscle protein synthetic response to amino acid ingestion in healthy young men. Diabetes. 2015;64:1615–20.

Vogt S, Heinrich L, Schumacher YO, Grosshauser M, Blum A, König D, Berg A, Schmid A. Energy intake and energy expenditure of elite cyclists during preseason training. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26:701–6.

Impey SG, Hammond KM, Shepherd SO, Sharples AP, Stewart C, Limb M, Smith K, Philp A, Jeromson S, Hamilton DL, Close GL, Morton JP. Fuel for the work required: a practical approach to amalgamating train-low paradigms for endurance athletes. Physiol Rep. 2016;4:e12803.

Lee-Young RS, Palmer MJ, Linden KC, LePlastrier K, Canny BJ, Hargreaves M, Wadley GD, Kemp BE, McConell GK. Carbohydrate ingestion does not alter skeletal muscle AMPK signalling during exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:566–73.

Ørtenblad N, Nielsen J, Saltin B, Holmberg H-C. Role of glycogen availability in sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ kinetics in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2011;589:711–25.

Duhamel TA, Perco JG, Green HJ. Manipulation of dietary carbohydrates after prolonged effort modifies muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum responses in exercising males. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:1100–10.

Gejl KD, Hvid LG, Frandsen U, Jensen K, Sahlin K, Ørtenblad N. Muscle glycogen content modifies SR Ca2+ release rate in elite endurance athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:496–505.

Costa RJ, Jones GE, Lamb KL, Coleman R, Williams JH. The effects of a high carbohydrate diet on cortisol and salivary immunoglobulin A (s-IgA) during a period of increase exercise workload amongst Olympic and Ironman triathletes. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26:880–6.

Jensen L, Gejl KD, Ørtenblad N, Nielsen JL, Bech RD, Nygaard T, Sahlin K, Frandsen U. Carbohydrate restricted recovery from long term endurance exercise does not affect gene responses involved in mitochondrial biogenesis in highly trained athletes. Physiol Rep. 2015;12:e121814.

Gejl KD, Thams L, Hansen M, Rokkedal-Lausch T, Plomgaard P, Nybo L, Larsen FJ, Cardinale DA, Jensen K, Holmberg HC, Vissing K, Ørtenblad N. No superior adaptations to carbohydrate periodization in elite endurance athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(12):2486–97.

Lane SC, Areta JL, Bird SR, Coffey VG, Burke LM, Desbrow B, Karagounis LG, Hawley JA. Caffeine ingestion and cycling power output in a low or normal muscle glycogen state. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:1577–84.

Gollnick PD, Piehl K, Saltin B. Selective glycogen depletion pattern in human skeletal muscle fibres after exercise of varying intensity and at varying pedalling rates. J Physiol. 1974;241:45–57.

De Bock K, Derave W, Ramaekers M, Richter EA, Hespel P. Fiber type-specific muscle glycogen sparing due to carbohydrate intake before and during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102 (1):183–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Samuel Impey, Mark Hearris, Kelly Hammond, Jonathan Bartlett, Julien Louis, Graeme Close and James Morton declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Impey, S.G., Hearris, M.A., Hammond, K.M. et al. Fuel for the Work Required: A Theoretical Framework for Carbohydrate Periodization and the Glycogen Threshold Hypothesis. Sports Med 48, 1031–1048 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0867-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0867-7